Anti-Catholicism: Difference between revisions

→Poland: Thousands ? Maybe hundreds... It was mor than thousands. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

*[[George Washington]] gave a formal address to U.S. Roman Catholics in 1789, welcoming them, "May the members of your society in America, animated alone by the pure spirit of Christianity, and still conducting themselves as the faithful subjects of our free government, enjoy every temporal and spiritual felicity."<ref name="Tme"> The Bible Tells Me So: Uses and Abuses of Holy Scripture, Jim Hill and Rand Cheadle, 1996, Anchor Books/Doubleday, p. 82-85 </ref> |

*[[George Washington]] gave a formal address to U.S. Roman Catholics in 1789, welcoming them, "May the members of your society in America, animated alone by the pure spirit of Christianity, and still conducting themselves as the faithful subjects of our free government, enjoy every temporal and spiritual felicity."<ref name="Tme"> The Bible Tells Me So: Uses and Abuses of Holy Scripture, Jim Hill and Rand Cheadle, 1996, Anchor Books/Doubleday, p. 82-85 </ref> |

||

*[[Harry Truman]] as President walked out during a sermon at the [[First Baptist Church]] in [[Washington, D.C.]] when the minister began preaching against federal policy that would give diplomatic recognition to the Vatican.<ref name="Tme"/> |

*[[Harry Truman]] as President walked out during a sermon at the [[First Baptist Church]] in [[Washington, D.C.]] when the minister began preaching against federal policy that would give diplomatic recognition to the Vatican.<ref name="Tme"/> |

||

*[[John F. Kennedy]] was the first, and so far only, Catholic to be elected President. |

*[[John F. Kennedy]] was the first, and so far only, Catholic to be elected President{{Fact|date=December 2008}}. |

||

=== Catholic countries === |

=== Catholic countries === |

||

Revision as of 06:25, 15 December 2008

Anti-Catholicism is a generic term for discrimination, hostility or prejudice directed at the Roman Catholic Church or its members. The term also applies to the religious persecution of Catholics or to a "religious orientation opposed to Catholicism."[1] In the Early Modern period, the Catholic Church struggled to maintain its traditional religious and political role in the face of rising secular powers in Europe. As a result of these struggles, there arose a hostile attitude towards the considerable political, social, spiritual and religious power of the pope and the Catholic clergy in the form of "anti-clericalism". To this was added the epochal crisis over its spiritual authority represented by the Protestant Reformation giving rise to sectarian conflict. In contemporary times anti-Catholicism has assumed various forms, including the persecution of Catholics as members of a religious minority in some localities, assaults by governments upon Catholic faithful, discrimination, and virulent attacks on clergy and laity.

Origins

Protestant and Reformed Christian countries

Beginning with Martin Luther, Protestants attacked the Pope as representing the power of the Anti-Christ and the Catholic Church as representing the Whore of Babylon prophesied in the Book of Revelation.[2] The identification of the Papacy as the Anti-Christ was an article of faith for many Protestant denominations:

- "25.6. There is no other head of the Church but the Lord Jesus Christ: nor can the Pope of Rome in any sense be head thereof; but is that Antichrist, that man of sin and son of perdition, that exalts himself in the Church against Christ, and all that is called God.

- The London Baptist Confession of 1689:

- 26.4. The Lord Jesus Christ is the Head of the church, in whom, by the appointment of the Father, all power for the calling, institution, order or government of the church, is invested in a supreme and sovereign manner; neither can the Pope of Rome in any sense be head thereof, but is that antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalteth himself in the church against Christ.

Referring to the Book of Revelation, Edward Gibbon stated that "The advantage of turning those mysterious prophecies against the See of Rome, inspired the Protestants with uncommon veneration for so useful as ally".[3]Protestants also condemned the Catholic policy of mandatory celibacy for priests, and the rituals of fasting and abstinence during Lent, as contradicting the clause stated in 1 Timothy 4:1–5, warning against doctrines that "forbid people to marry and order them to abstain from certain foods, which God created to be received with thanksgiving by those who believe and who know the truth." Partly as a result of the condemnation, many non-Catholic churches allow priests to marry and/or view fasting as a choice rather than an obligation.

England

Instutitional anti-Catholicism in England began with the English Reformation under Henry VIII. The Act of Supremacy of 1534 declared the English crown to be 'the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England' in place of the pope. Any act of allegiance to the latter was considered treasonous because the papacy claimed both spiritual and political power over its followers. It was under this act that saints Thomas More and John Fisher were executed and became martyrs to the Catholic faith.

The Act of Supremacy (which asserted England's independence from papal authority) was repealed in 1554 by Henry's daughter Queen Mary I (who was a devout Roman Catholic) when she reinstituted Catholicism as England's state religion. Another Act of Supremacy was passed in 1559 under Elizabeth I, along with an Act of Uniformity which made worship in Church of England compulsory. Anyone who took office in the English church or government was required to take the Oath of Supremacy; penalties for violating it included hanging and quartering. Attendance at Anglican services became obligatory—those who refused to attend Anglican services, whether Roman Catholics or Protestants (Puritans), were fined and physically punished as recusants.

In the time of Elizabeth I, the persecution of the adherents of the Reformed religion, both Anglicans and Protestants alike, which had occurred during the reign of her elder half-sister Queen Mary I was used to fuel strong anti-Catholic propaganda in the hugely influential Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Those who had died in Mary's reign, under the Marian Persecutions, were effectively canonised by this work of hagiography. In 1571 the Convocation of the English Church ordered that copies of the Book of Martyrs should be kept for public inspection in all cathedrals and in the houses of church dignitaries. The book was also displayed in many Anglican parish churches alongside the Holy Bible. The passionate intensity of its style and its vivid and picturesque dialogues made the book very popular among Puritan and Low Church families, Anglican and Protestant nonconformist, down to the nineteenth century. In a period of extreme partisanship on all sides of the religious debate, the exaggeratedly partisan church history of the earlier portion of the book, with its grotesque stories of popes and monks, contributed to fuel anti-Catholic prejudices in England, as did the story of the sufferings of several hundred Reformers (both Anglican and Protestant) who had been burnt at the stake under Mary and Bishop Bonner.

Anti-Catholicism among many of the English was grounded in the fear that the pope sought to reimpose not just religio-spiritual authority over England but also secular power of the country; this was seemingly confirmed by various actions by the Vatican. In 1570, Pope Pius V sought to depose Elizabeth with the papal bull Regnans in Excelsis, which declared her a heretic and purported to dissolve the duty of all Elizabeth's subjects of their allegiance to her. This rendered Elizabeth's subjects who persisted in their allegiance to the Catholic Church politically suspect, and made the position of her Catholic subjects largely untenable if they tried to maintain both allegiances at once.

In 1588 one Elizabethian loyalist cited the failed invasion of England by the Spanish Armada as an attempt by Philip II of Spain to put into effect the Pope's decree. In truth, King Philip II was attempting to claim the throne of England he felt he had as a result of being the widower of Mary I of England.

Elizabeth's resultant persecution of Catholic Jesuit missionaries led to many executions at Tyburn. Those priests who suffered there are considered martyrs by the Catholic church; though at the time, they were considered traitors to England. In recent decades, a convent has been established nearby to pray for their souls.

Later several accusations fueled strong anti-Catholicism in England including the Gunpowder Plot, in which Guy Fawkes and other Catholic conspirators where accused of planning to blow up the English Parliament while it was in session. The Great Fire of London in 1666 was blamed on the Catholics and an inscription ascribing it to 'Popish frenzy' was engraved on the Monument to the Great Fire of London, which marked the location where the fire started (this inscription was only removed in 1831). The "Popish Plot" involving Titus Oates further exacerbated Anglican-Catholic relations.

The beliefs that underlie the sort of strong anti-Catholicism once seen in the United Kingdom were summarized by William Blackstone in his Commentaries on the Laws of England:

- As to papists, what has been said of the Protestant dissenters would hold equally strong for a general toleration of them; provided their separation was founded only upon difference of opinion in religion, and their principles did not also extend to a subversion of the civil government. If once they could be brought to renounce the supremacy of the pope, they might quietly enjoy their seven sacraments, their purgatory, and auricular confession; their worship of relics and images; nay even their transubstantiation. But while they acknowledge a foreign power, superior to the sovereignty of the kingdom, they cannot complain if the laws of that kingdom will not treat them upon the footing of good subjects..

- — Bl. Comm. IV, c.4 ss. iii.2, p. *54

The gravamen of this charge, then, is that Catholics constitute an imperium in imperio, a sort of fifth column of persons who owe a greater allegiance to the Pope than they do to the civil government, a charge very similar to that repeatedly leveled against Jews. Accordingly, a large body of British laws, such as the Popery Act 1698, collectively known as the penal laws, imposed various civil disabilities and legal penalties on recusant Catholics.

A change of attitude was eventually signalled by the Papists Act 1778 in the reign of George III. Under this Act an oath was imposed, which besides being a declaration of loyalty to the reigning sovereign, contained an abjuration of the Charles Edward Stuart the Catholic Pretender to the throne and of certain doctrines attributed to Catholics, as that excommunicated princes may lawfully be murdered, that no faith should be kept with heretics, and that the Pope has temporal as well as spiritual jurisdiction in the realm. Those taking this oath were exempted from some of the provisions of the Popery Act. The section as to taking and prosecuting priests were repealed, as also the penalty of perpetual imprisonment for keeping a school. Catholics were also enabled to inherit and purchase land, nor was a Protestant heir any longer empowered to enter and enjoy the estate of his Catholic kinsman. However the passing of this act was the occasion of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots (1780) in which the violence of the mob was especially directed against Lord Mansfield who had balked at various prosecutions under the statutes now repealed.[4] The repeal of the penal laws culminated in the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829.

Despite the Emancipation Act, however, anti-Catholic attitudes persisted throughout the 19th century, particularly after the influx of Irish immigrants to England during the Great Famine.

The reestablishment of the Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy in 1850 was followed by a frenzy of anti-Catholic feeling (often stoked by newspapers). Examples include an effigy of Cardinal Wiseman, the new head of the restored Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy, being paraded through the streets and burned on Bethnal Green and graffiti proclaiming 'No popery!' being chalked on walls.[5]

Even now, as a result the of 1701 Act of Settlement, any member of the British royal family must renounce his or her claim to the throne if they join the Catholic Church or marry a Roman Catholic (this occurred as recently as 2008).[6]

Ireland

Ireland's Catholic majority has been subject to persecution from the time of the English Reformation under Henry VIII. This persecution intensified when the Gaelic clan system was completely destroyed by the governments of Elizabeth I and her successor, James I. Land was appropriated either by the conversion of native Anglo-Irish aristocrats or by forcible seizure. Many Catholics were dispossessed and their lands given to Anglican and Protestant settlers from Britain, (however it should be noted that the first plantation in Ireland was a Catholic plantation under Queen Mary I, for more see Plantations of Ireland).

In order to cement the power of the Anglican Ascendancy, political and land-owning rights were denied to Ireland's Catholics by law, following the Glorious Revolution in England and consequent turbulence in Ireland. The Penal Laws, established first in the 1690s, assured Church of Ireland control of political, economic and religious life. The Mass, ordination, and the presence in Ireland of Catholic Bishops were all banned, although some did carry on secretly. Catholic schools were also banned, as were all voting franchises. Violent persecution also resulted, leading to the torture and execution of many Catholics, both clergy and laity. Since then, many have been canonised and beatified by the Vatican, such as Saint Oliver Plunkett, Blessed Dermot O'Hurley, and Blessed Margaret Ball.

Although some of the penal laws restricting Catholic access to landed property were repealed between 1778 and 1782 this did not end anti-Catholic agitation and violence. Catholic competition with Protestants in County Armagh for leases intensified, driving up prices and provoking resentment of Anglicans and Protestants alike. Then in 1793, the Catholic Relief Act enfranchised forty shilling freeholders in the counties, thus increasing the political value of Catholic tenants to landlords. In addition, Catholics began to enter the linen weaving trade, thus depressing Protestant wage rates. From the 1780s the Protestant Peep O'Day Boys grouping began attacking Catholic homes and smashing their looms. In addition, the Peep O'Day Boys disarmed Catholics of any weapons they were holding.[7] A Catholic group called the Defenders was formed in response to these attacks. This climaxed in the Battle of the Diamond on 21 September 1795 outside the small village of Loughgall between Peep O' Day boys and the Defenders.[8] Roughly 30 Catholic Defenders, but none of the better armed Peep O'Day Boys were killed in the fight. Hundreds of Catholic homes and at least one Church were burnt out in the aftermath of the skirmish.[9] After the battle Daniel Winter, James Wilson and James Sloan changed the name of the Peep O' Day Boys to the Orange Order devoted to maintaining the Protestant ascendency.

Though more of the Penal Laws were repealed and Catholic Emancipation in 1829 ensured political representation at Westminster significant anti-Catholic hostility remained, especially in Belfast where the Catholic population was in the minority. In the same year, the Presbyterians, reaffirmed at the Synod of Ulster that the Pope was the anti-Christ and joined the Orange Order in large numbers when the latter organisation opened its doors to all non-Catholics in 1834. As the Orange order grew, violence against Catholics became a regular feature of Belfast life.[10] Towards the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth century when Irish Home Rule became imminent, Protestant fears and opposition towards it were articulated under the slogan "Home Rule means Rome Rule".

Scotland

In the 16th century, the Scottish Reformation resulted in Scotland's conversion to Presbyterianism through the Church of Scotland. The revolution resulted in a powerful hatred of the Roman Church. High Anglicism also came under intense persecution also after Charles I attempted to reform the Church of Scotland. The attempted reforms caused chaos, however, because they were seen as being overly Catholic in form in being based heavily on sacraments and ritual.

Over the course of later mediæval and early modern history violence against Catholics has broken out, often resulting in deaths, such as the torture and execution of Saint John Ogilvie and the execution of a Jesuit priest.

In the last 150 years, Irish immigration to Scotland increased dramatically and at the beginning of the immigration period Catholics were treated like second class citizens. As time has gone on Scotland has, however, become much more open to other religions and Catholics have seen the nationalisation of their schools and the restoration of the Church hierarchy. The Orange Order has also grown in numbers in recent times. This growth is, however, attributed mainly to the rivalry between Rangers and Celtic football clubs as opposed to actual hatred of Catholics.[11]

United States

John Highham described anti-Catholic bigotry as "the most luxuriant, tenacious tradition of paranoiac agitation in American history".[12] The bigotry which was prominent in the United Kingdom was exported to the United States. Two types of anti-Catholic rhetoric existed in colonial society. The first, derived from the heritage of the Protestant Reformation and the religious wars of the sixteenth century, consisted of the "Anti-Christ" and the "Whore of Babylon" variety and dominated Anti-Catholic thought until the late seventeenth century. The second was a more secular variety which focused on the supposed intrigue of the Catholics intent on extending medieval despotism worldwide.[13]

Historian Arthur Schlesinger Sr. has called Anti-Catholicism "the deepest-held bias in the history of the American people."[14]

The roots of American Anti-Catholicism go back to the Reformation, whose ideas about Rome and the papacy travelled to the New World with the earliest settlers. These settlers were, of course, predominantly Protestant, and many opposed not only Catholicism but also the remaining Catholic traditions of the official Anglican State Church, the Church of England, which they felt was insufficiently Reformed. A large part of American culture is a legacy of Great Britain, and an enormous part of its religious culture a legacy of the more extreme Protestant tendencies of the English Reformation. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis, in his landmark book American Catholicism, first published in 1956, wrote bluntly that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia." Proscriptions against Roman Catholics were included in colonial charters and laws, and, as Monsignor Ellis noted wryly, nothing could bring together warring Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers faster than their common hatred of the Church of Rome. Such antipathy continued throughout the 18th century. Indeed, the virtual penal status of the Catholics in many of the colonies made even the appointment of bishops unthinkable in the early years of the Republic. Another result of this was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant, that Anglicans elsewhere had shown some care in using too prominently due to their own reservations about the nature of the Church of England, and other Anglican bodies, vis-à-vis later radical reformers who were happier to use the term Protestant.

In 1788, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil." [15].

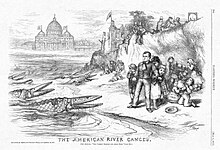

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the nineteenth century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Fearing the end of time, some American Protestants who believed they were God's chosen people, went so far as to claim that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon in the Book of Revelation.[16] The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.[17] This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for raising the taxes of the country[citation needed] as well as for spreading violence and disease. The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore as its presidential candidate in 1856.

Acts of U.S. Presidents against Anti-Catholicism

- George Washington gave a formal address to U.S. Roman Catholics in 1789, welcoming them, "May the members of your society in America, animated alone by the pure spirit of Christianity, and still conducting themselves as the faithful subjects of our free government, enjoy every temporal and spiritual felicity."[18]

- Harry Truman as President walked out during a sermon at the First Baptist Church in Washington, D.C. when the minister began preaching against federal policy that would give diplomatic recognition to the Vatican.[18]

- John F. Kennedy was the first, and so far only, Catholic to be elected President[citation needed].

Catholic countries

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious (generally Catholic) institutional power and influence in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen. It suggests a more active and partisan role than mere laïcité. The goal of anti-clericalism is sometimes to reduce religion to a purely private belief-system with no public profile or influence. However, many times it has included outright suppression of all aspects of faith.

Anti-clericalism has at times been violent, leading to murders and the desecration, destruction and seizure of church property. Anti-clericalism in one form or another has existed throughout most of Christian history, and is considered to be one of the major popular forces underlying the 16th century reformation. Some of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, including Voltaire, continually attacked the Catholic Church, both its leadership and priests, claiming that many of its clergy were morally corrupt. These assaults in part led to the suppression of the Jesuits, and played a major part in the wholesale attacks on the very existence of the Church during the French Revolution in the Reign of Terror and the program of dechristianization. Similar attacks on the Church occurred in Mexico and in Spain in the twentieth century.

France

During the French Revolution (1789-95) church property was confiscated by the new government as part of a process of Dechristianization. The French invasions of Italy (1796-99) included an assault on Rome and the exile of Pope Pius VI in 1798. Relations improved from 1802 to 1870. France's Third Republic was cemented by anti-clericalism, the desire to secularise the State and social life, faithful to the French Revolution.[19] In the Affaire Des Fiches, in France in 1904-1905, it was discovered that the militantly anticlerical War Minister under Emile Combes, General Louis André, was determining promotions based on the French Masonic Grand Orient's huge card index on public officials, detailing which were Catholic and who attended Mass, with the goal of preventing their promotions.[20]

Mexico

Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles's enforcement of previous anti-Catholic legislation denying priests' rights, enacted as the Calles Law, prompted the Mexican Episcopate to suspend all Catholic worship in Mexico from August 1, 1926 and sparked the bloody Cristero War of 1926-1929 in which some 50,000 peasants took up arms against the government. Their slogan was "Viva Cristo Rey!" (long live Christ the King). Some of the Catholic casualties of this struggle are known as the Saints of the Cristero War.[21][22] Events relating to this were famously portrayed in the novel The Power and the Glory by Graham Greene.[23][24] The persecution of Catholics was most severe in the state of Tabasco under the Governor Tomás Garrido Canabal[citation needed]. Under the rule of Garrido many priests were killed, all Churches in the state were closed and priests who still survived were forced to marry or flee at risk of losing their lives[citation needed]. The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 and 1934 at least 40 priests were killed.[21] Where there were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, in 1934 there were only 334 priests licensed by the government to serve fifteen million people, the rest having been eliminated by emigration, expulsion and assassination.[25][21] The persecution was such that by 1935, 17 states were left with no priests at all.[26]

Haiti

François and Jean-Claude Duvalier's family dictatorship of Haiti wanted to weaken the control of the Catholic Church by bringing Vodou "openly into the political process", according to Michel S. LaGuerre in Voodoo and Politics in Haiti.[This quote needs a citation]

Spain

Anti-clericalism in Spain at the start of the Spanish Civil War resulted in the killing of almost 7,000 clergy, the destruction of hundreds of churches and the persecution of lay people in Spain's Red Terror.[27] Hundreds of Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War have been beatified and hundreds more were beatified in October 2007.[28][29]

Colombia

Anti-Catholic and anti-clerical sentiments, some spurred by an anti-clerical conspiracy theory which was circulating in Colombia during the mid-twentieth century led to persecution of Catholics and killings, most specifically of the clergy, during the events known as La Violencia.[30]

Poland

Catholicism in Poland, the religion of the vast majority of the population, was severely persecuted during World War II following the Nazi invasion of the country and its subsequent annexation into Germany. An undetermined number of Catholics of Polish descent, probably numbering in the thousands[citation needed], are believed to have been murdered during the Holocaust.

Catholicism continued to be persecuted under the Communist regime from the 1950s. Current Stalinist ideology claimed the Church and religion in general was about to disintegrate. To begin with Archbishop Wyszyński entered into an agreement with the Communist authorities, which was signed on 14 February 1950 by the Polish episcopate and the government. The Agreement regulated the matters of the Church in Poland. However, in May of that year, the Sejm breached the Agreement by passing a law for the confiscation of Church property.

On 12 January 1953, Wyszyński was elevated to the rank of cardinal by Pius XII as another wave of persecution began in Poland. When the bishops voiced their opposition to state interference in ecclesiastical appointments, mass trials and the internment of priests began - the cardinal being one of its victims. On 25 September 1953 he was imprisoned at Grudziądz, and later placed under house arrest in monasteries in Prudnik near Opole and in Komańcza in the Bieszczady Mountains. He was not released until 26 October 1956.

Pope John Paul II, who was born in Poland as Karol Wojtyla, often cited the persecution of Polish Catholics in his stance against Communism.

Orthodox Christian countries

Less widely known in the West has been the anti-Catholicism found in countries where the Eastern or Orthodox Christian Churches have prevailed historically. The prejudice and persecution of Catholics in those countries can be dated back to 1054 [citation needed] when the Great Schism between Western-rite and Eastern-rite Christians occurred. This anti-Roman Catholicsm may stem from perceived atrocities of the Roman Catholic church against the Orthodox including the Sack of Constantinople which involved the murdering Orthodox Clergy this after the same occurred in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre during the First Crusade which culminated into the establishment of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem of the Kingdom of Jerusalem which was created over the Orthodox clergy. This along with the looting, conversion of Orthodox Churches to Roman Catholic churches throughout the crusades. Including also the thief of sacred Christian relics, from Orthodox Christian Holy Sites like the church of Holy Wisdom. Both camps of Christians have traditionally viewed each other as heretics[citation needed], and have excommunicated and anathematised each other repeatedly.[citation needed] Recent decades has seem some softening of official mutual antipathy, though the roots of this are deep and difficult to overcome.[citation needed] In some cases in modern times the conflict has intensified like in the Balkans, this again maybe due to perceived atrocities committed by Roman Catholics, including forced conversion and then execution of the Serbian Orthodox by the Ustashe.[31] This done in order to insure that the converted Orthodox went to Heaven rather then, convert back to Orthodox Christianity.[32] For a one sided view of this, coverage is given in the section detailing the former Soviet Union, below, though that account is by no means exhaustive.[citation needed]

Anti-Catholicism in popular culture

Literature

Anti-Catholic stereotypes are a long-standing feature of Anglo-Saxon literary, sub-literary and even pornographic traditions. Gothic fiction is particularly rich in this regard with the figure of the lustful priest, the cruel abbess, the immured nun, and the sadistic inquisitor appearing in such works as The Italian by Ann Radcliffe, The Monk by Matthew Lewis, Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin and "The Pit and the Pendulum" by Edgar Allan Poe.[33]

Such gothic fiction may have inspired Rebecca Reed's Six Months in a Convent which describes her alleged captivity by an Ursuline order near Boston in 1832.[34][35] Her claims inspired an angry mob to burn down the convent, and her narrative, released three years later as the rioters were tried, famously sold 200,000 copies in one month. Reed's book was soon followed by another bestselling fraudulent exposé, Awful Disclosures of the Hotel-Dieu Nunnery, (1836) in which Maria Monk claimed that the convent served as a harem for Catholic priests, and that any resulting children were murdered after baptism. Col. William Stone, a New York city newspaper editor, along with a team of Protestant investigators, made inquiry into the claims of Monk, inspecting the convent in the process. Col. Stone's investigation concluded there was no evidence that Maria Monk "had ever been within the walls of the cloister".

Reed's book became a best-seller, and Monk or her handlers hoped to cash in on the evident market for anti-Catholic horror fiction by their offering. The tale of Maria Monk was, in fact, clearly modelled on the Gothic novels that were popular in the early 19th century, a literary genre that had already been used for anti-Catholic sentiments in works such as Matthew Lewis' The Monk. Monk's story explores the genre-defining elements of a young, innocent woman being trapped in a remote, old, and gloomily picturesque estate; she learns the dark secrets the place contains, and after harrowing adventures makes her escape.[36][37]

The anti-Catholic Gothic tradition continued with Charlotte Brontë's semi-autobiographical novel Villette (1853) which explores the culture clash between the heroine Lucy’s English Protestantism and the Catholicism of her environment at her school in 'Villette' (aka Brussels), Belgium, before coming to the magisterial pronouncement that 'God is not with Rome'.

Pornography has been the vehicle for anti-Catholic sentiments from Denis Diderot's La Religieuse (1798), to contemporary nunsploitation films. These latter, although often seen as pure exploitation films, often contain criticism against religion in general and the Catholic church in particular. Indeed, some of the protagonists voice a feminist consciousness and a rejection of their subordinated social role. For instance at the end of The Nun and the Devil, based on the true events of the suppression of the Convent of Sant Archagelo at Naples in the 16th century, a condemned nun launches a bitter attack against the church hierarchy. Many of these films were made in countries where the Catholic church is dominant, such as Italy and Spain.[38]

In a chapter of Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov called The Grand Inquisitor, the Catholic Church convicts a returned from Heaven to Earth Jesus Christ of heresy and is portrayed as a servant of Satan.[citation needed] In Notes from Underground the main character thinks about making the world a better place by eliminating or overthrowing the Pope. [citation needed]

Dan Brown's best-selling novel The Da Vinci Code depicts the Catholic Church as determined to hide the truth about Mary Magdelene. An article in an April 2004 issue of National Catholic Register maintains that the "The Da Vinci Code claims that Catholicism is a big, bloody, woman-hating lie created out of pagan cloth by the manipulative Emperor of Rome". An earlier book by Brown Angels and Demons, depicts the Church as involved in an elemental battle with the Illuminati.

Cinema

The Spanish film director Luis Buñuel was a fierce critic of what he saw as the pretension and hypocrisy of the Catholic Church. Many of his most famous films demonstrate this:

Un chien andalou (1929): A man drags pianos, upon which are piled several priests, among other things.

L'Âge d'or (1930): A bishop is thrown out a window, and in the final scene one of the culprits of the 120 days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade is portrayed by an actor dressed in a way that he would be recognized as Jesus.

Ensayo de un crimen (1955): A man dreams of murdering his wife while she's praying in bed dressed all in white.

Simon of the Desert (1965): The devil tempts the saint by taking the form of a naughty, bare-breasted little girl singing and showing off her legs. At the end of the film, the saint abandons his ascetic life to hang out in a jazz club.

Nazarin (1959): The pious lead character wreaks ruin through his attempts at charity.

Viridiana (1961): A well-meaning young nun tries unsuccessfully to help the poor.

The Milky Way (1969): Two men travel the ancient pilgrimage road to Santiago de Compostela and meet the embodiments of various heresies along the way. One dreams of anarchists shooting the Pope (recognisably Pope Paul VI).

The films of Buñuel (who reportedly 'thanked God he was an atheist') initially scandalised the Catholic church. For instance Viridiana was denounced by the Vatican and, in Catholic Spain, where the film was produced, an attempt was made to destroy all copies; Catholic Italy sentenced Buñuel, in absentia, to a year in jail, whilst in Catholic Belgium copies of the film were seized and mutilated. Latterly, however, there was a change of attitude. For instance the US National Catholic Film Office, gave Nazarin an award, recognising its spiritual value, and the heretical Milky Way was screened at the Festival of Cinema of Religious and Human Values in Valladolid. Some of Buñuel's free thinking friends even alleged that he had received Vatican money for the latter film. Ironically Buñuel's last months were enlivened by his friendship, in his last months, with a Catholic priest, Father Julian Pablo, with whom he indulged in theological wrangles over points of Catholic dogma.[39]

Modern Anti-Catholic polemics

As well as standard Protestant polemics which likened Catholicism to the Anti-Christ and the Whore of Babylon other themes of modern anti-Catholic controversialists included accusations of paganism, idolatry and conspiracy theories which accuse the church of seeking world domination.

Standard Protestant polemics are represented by such writers as American evangelical author John Dowling, in his best-selling[citation needed] The History of Romanism. In this work he accused the Catholic church of being 'the bitterest foe of all true churches of Christ—that she possesses no claim to be called a Christian church—but, with the long line of corrupt and wicked men who have worn her triple crown, that she is ANTI-CHRIST' (John Dowling, The History of Romanism 2nd edition, 1852, pp. 646-47).

Alexander Hislop's psuedohistorical work, The Two Babylons (1858) asserted that the Roman Catholic Church originated from a Babylonian mystery religion, claiming that its doctrines and ceremonies are a veiled continuation of Babylonian paganism.

The renegade priest Charles Chiniquy's 50 Years In The Church of Rome and The Priest, the Woman and the Confessional (1885) also depicted Catholicism as pagan.

Avro Manhattan's books,Vatican Moscow Alliance (1982), The Vatican Billions (1983), and The Vatican's Holocaust (1986) advance the view that the Church engineers wars for world domination.

Hislop's and Chiniquy's nineteenth century polemics and Avro Manhattan's work form part of the basis of a series of tracts by the noted modern anti-Catholic and comic book evangelist Jack Chick who also accuses the papacy of supporting Communism, of using the Jesuits to incite revolutions, and of masterminding the Holocaust. According to Chick, the Catholic Church is the "Whore of Babylon" referred to in the Book of Revelation, and will bring about a Satanic New World Order before it is destroyed by Jesus Christ. Chick claims that the Catholic Church infiltrates and attempts to destroy or corrupt all other religions and churches, and that it uses various means including seduction, framing, and murder to silence its critics. Drawing on the ideas of Alberto Rivera, Chick also claims that the Catholic Church helped mould Islam as a tool to lure people away from Christianity in what he calls the Vatican Islam Conspiracy.

Richard Dawkins in his latest best-selling book The God Delusion (2006) asserts that a Catholic upbringing promotes guilt-trips referring[40] to the "semi-permanent state of morbid guilt suffered by a Catholic possessed of normal human frailty and less than normal intelligence" . Discussing the consequences of clerical sexual abuse in Ireland, he further suggests that "horrible as sexual abuse no doubt was, the damage was arguably less than the long-term psychological damage inflicted by bringing the child up Catholic in the first place".[41]

David Ranan’s Double Cross: The Code of the Catholic Church asks three questions: should the pope be sacked? Should the Vatican be dissolved? Can the Catholic Church be saved? His analysis of the Church’s history, dogma and present day strategies leads to the conclusion that the Catholic Church is incapable of accepting her culpability and therefore unlikely to change.[42]

Author David Yallop has followed up his best-selling book In God's Name (1984), which claimed that Pope John Paul I was killed by corrupt Vatican schemers (see Pope John Paul I conspiracy theories) with another The Power and the Glory: Inside the Dark Heart of John Paul II's Vatican (2007) which claims that Pope John Paul II was in league with Soviet power. Yallop enlarges on claims of priestly sexual abuse and repeats the other standard anti-Catholic tropes listed above together with a new one that St Maximilian Kolbe, the Polish priest who died in place of a young married man at Auschwitz, had previously endorsed the anti-Jewish Protocols of the Elders of Zion. There is no reference for this claim and just thirteen footnotes in the entire 530 pages.[43]

Anti-Catholic Satire and Humour

The Catholic church has been a target for satire and humour, from the time of the Reformation to the present day. Such satire and humour ranges from mild burlesque to vicious attacks[citation needed]. Catholic clergy and lay organizations such as the Catholic League monitor for particularly offensive and derogatory incidences and voice their objections and protests.[44]

Sexuality

Accusations of deviant sexuality have provided a rich field for anti-Catholic polemicists since the time of the Reformation.

Under Henry VIII, even before he broke with Rome, lurid tales of sexual deviancy by monks and nuns were part of the justification for the Dissolution of the Monasteries. According to a later commentator the alleged carnal misdeeds of the monks and nuns were recorded in a 'Black Book' wherein was recorded "the vile lives and abhominable factes in murders of their bretherene, in sodomyes and whordomes, in destroying children, in forging deedes and other horrors of life" (sic).[45] R.W. Dixon in his History of the Church of England justified the Dissolution of the monasteries on the grounds that they were under "the condemnation of Sodom and Gomorrah" i.e. some monks and nuns were homosexual.[46] Prior to the Dissolution its instigator Thomas Cromwell had decreed death by hanging for homosexuals through the Buggery Act of 1533: the first time the death penalty had been applied for this offence in England.[47]

In the twentieth century the Nazi government denounced the Catholic Church as "awash with sex fiends" (the Nazi Churches minister claimed that 7,000 clergy had been convicted of sex crimes between 1933 and 1937 while "the true figure seems to have been 170, of whom many had left the religious life prior to their offences.")[48] These accusations were part of a campaign by some members of the Nazi party, including Joseph Goebbels, to reduce the influence of the Catholic Church in Nazi Germany during the second half of the 1930s.[49]

Lately sexual abuse by representatives of the Catholic church has been highlighted in such films as The Magdalene Sisters (2002). However the veracity of the bestselling Kathy's Story by Kathy O'Beirne which details physical and sexual abuse suffered in a Magdalene laundry in Ireland has been questioned in a new book entitled Kathy's Real Story by Hermann Kelly. In this book it is alleged that false allegations against the priesthood are being fueled by a government compensation scheme for victims.[50]

Philip Jenkins, an Episcopalian and Professor of History and Religious Studies at Penn State University, published the 1996 book Pedophiles and Priests: Anatomy of a Contemporary Crisis in which he claims that the Catholic Church is being unfairly singled out by a secular media which he claims fails to highlight similar sexual scandals in other religious groups, such as the Anglican Communion, various Protestant churches, and the Jewish and Islamic communities. He also claims that the Catholic Church may have a lower incidence of molesting priests than Churches that allow married clergy because statistically child molestation generally occurs within families but Latin-rite Catholic priests do not have families, and the Catholic Church only allows married priests in a few of its rites. He also claims that the term "pedophile priests" widely used in the media, implies a distinctly higher rate of child molesters within the Catholic priesthood when in reality the incidence is lower than most other segments of society".[51]

Anti-Catholicism today

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

United States

Philip Jenkins, an Episcopalian historian, in The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 0-19-515480-0) maintains that some people who otherwise avoid offending members of racial, religious, ethnic or gender groups have no reservations about venting their hatred of Catholics. Earlier in the twentieth century, Harvard professor Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. characterized prejudice against Catholics as "the deepest bias in the history of the American people",[52] and Pulitzer Prize-winning Mount Holyoke professor Peter Viereck once commented that "Catholic baiting is the anti-Semitism of the liberals."[53]

A May 12, 2006, Gallup states that 30% of Americans have an unfavourable view of the Catholic faith with 57% having a favourable view. This is a higher unfavourability rate than in 2000, but considerably lower than in 2002. While Protestants and Catholics themselves had a majority with a favourable view, those who are not Christian or are irreligious had a majority with an unfavourable view, but in part this represented a negative view of all forms of Christianity. The Catholic Church's doctrines, the priest sex abuse scandal, and "honoring Mary" and asking saints to pray for or with the person praying were top issues for those who disapproved. On the other hand, Catholicism's view on homosexuality, and the celibate priesthood were low on the list of grievances for those who held an unfavourable view of Catholicism.[54] That stated a more recent Gallup Poll indicated only 4% of Americans have a "very negative" view of Catholics.[55]

Sexuality, contraception and abortion

Many feminists and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender activists criticize the Catholic Church for its policies on issues relating to sexuality, contraception and abortion. In 1989 members of the ACT UP and WHAM! disrupted a Sunday Mass at Saint Patrick’s Cathedral to protest the Church’s position on homosexuality, abortion, safer sex education and the use of condoms. One hundred and eleven protesters were arrested outside the Cathedral, and at least one protester inside threw used condoms at a Church altar and desecrated the Eucharist during Mass.[56]

Anti-Catholicism in the entertainment industry

According to James Martin, S.J. the U.S. entertainment industry is of "two minds" about the Catholic Church. He argues that,

On the one hand, film and television producers seem to find Catholicism irresistible. There are a number of reasons for this. First, more than any other Christian denomination, the Catholic Church is supremely visual, and therefore attractive to producers and directors concerned with the visual image. Vestments, monstrances, statues, crucifixes - to say nothing of the symbols of the sacraments - are all things that more "word oriented" Christian denominations have foregone. The Catholic Church, therefore, lends itself perfectly to the visual media of film and television. You can be sure that any movie about the Second Coming or Satan or demonic possession or, for that matter, any sort of irruption of the transcendent into everyday life, will choose the Catholic Church as its venue[57]

Second, the Catholic Church is still seen as profoundly "other" in modern culture and is therefore an object of continuing fascination. As already noted, it is ancient in a culture that celebrates the new, professes truths in a postmodern culture that looks skeptically on any claim to truth, and speaks of mystery in a rational, post-Enlightenment world. It is therefore the perfect context for scriptwriters searching for the "conflict" required in any story.[57]

Martin argues that, despite this fascination with the Catholic Church, the entertainment industry also holds contempt for the Church.[57]"It is as if producers, directors, playwrights and filmmakers feel obliged to establish their intellectual bona fides by trumpeting their differences with the institution that holds them in such thrall."[57] Martin suggests that "it is television that has proven the most fertile ground for anti- Catholic writing. Priests, when they appear on television shows, usually appear as pedophiles or idiots, and are rarely seen to be doing their jobs."[57]

One group that has systematically addressed anti-Catholicism is the Catholic League for Religious and Civil Rights which has organized protests and issued press releases over pop culture entertainment offerings and high-profile media events. Led by William Donohue, who also serves as the media spokesperson, the League interjects itself to present alternative views on many news stories. In October 1999 they purchased a full-page advertisement in The New York Times denouncing Vanity Fair magazine for its alleged anti-Catholic slant.[58][59]

England

Residual anti-Catholicism in England is represented by the burning of an effigy of the Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes at local celebrations on Guy Fawkes Night every 5 November.[60] This celebration has, however, largely lost any sectarian connotation and the allied tradition of burning an effigy of the Pope on this day has been discontinued - except in the town of Lewes, Sussex.[61]

Scotland

Although there is a popular perception in Scotland that anti-Catholicism is football related (specifically directed against fans of Celtic F.C.), statistics released in 2004 by the Scottish Executive showed that 85% of sectarian attacks were not football related.[62] Sixty-three percent of the victims of sectarian attacks are Catholics, but when adjusted for population size this makes Catholics between five and eight times more likely to be a victim of a sectarian attack than a Protestant.[62][63]

Due to the fact that many Catholics in Scotland today have Irish ancestry, there is a lot of overlap between anti-Irish racism and anti-Catholicism.[62] For example the word "Fenian" is often both pre- and suffixed by derogatory language by anti-Catholic bigots but may refer to either their religion or their Irishness.[63]

In 2003 the Scottish Parliament passed the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003 which included provisions to make an assault motivated by the perceived religion of the victim an aggravating factor.[64]

Northern Ireland

The recent Troubles in Northern Ireland were characterised by bitter sectarian antagonism and bloodshed between Irish Republicans who are principally Catholic, and Loyalists who are overwhelmingly Protestant.

Some of the most savage attacks were perpetrated by a Protestant gang dubbed the Shankill Butchers, led by Lenny Murphy, who was described as a psychopath and a sadist[65]. The gang gained notoriety by torturing and killing an estimated thirty Catholics, between 1972 and 1982. Most of their victims had no connection to the Provisional Irish Republican Army or any other republican groups but were killed for no other reason than their religious affiliation.[66] Murphy's killing spree is the theme of a British film called Resurrection Man (1998).

Church buildings were frequently attacked and mass-goers were harassed and prevented from attending mass by Loyalist paramilitaries. One of the most famous incidents was the attack on St Matthew's church by Loyalists on the night of 27 June 1970 when the Provisional IRA, led by Billy McKee repelled the attack with the death of at least four Loyalists and one IRA volunteer.[67][68]

At the moment sectarian killings in Northern Ireland have largely ceased, though bad feelings between Catholics and Protestants linger on. The Saville Inquiry, into the 1972 Bloody Sunday massacre of unarmed Catholics in Derry by the British army, has yet to report. Some forty "Peace walls" built to inhibit sectarian violence, still remain, dividing Protestant and Catholic areas in Belfast and elsewhere in the Province. Despite the achievements of the Peace process and the cessation of paramilitary violence there is no sign that these will be knocked down in the immediate future.

Former Soviet Union

In the former Soviet Union, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was persecuted just for its religious role in the community[citation needed], but at other times the Russian Orthodox Church was manipulated to combat Catholics on the grounds that this was a more "Russian" body.[citation needed]

Israel

The roots of Anti-Catholicism in Israel can be traced back to the origin of the Jewish state in 1948 when several villages with majority Catholic populations, such as Kafr Bir'im and Iqrit, were forcibly depopulated by the Israel Defence Forces.[69] Catholic priests have been expelled from the country, and dozens of churches have been occupied, closed or forcibly sold since 1948. More recently Israel has denied residence status to Catholic clerics and has attempted to block the appointment of Catholic bishops.[70] Israeli government attempts such as the failed 1998 effort to block the Holy See's appointment of Boutros Mouallem as archbishop of Galilee were condemned by the Vatican and other nations.[71] Suspicion and hostility towards Catholic clerics has led to incidents such as the October 2002 detention and harassment of Melkite Greek Catholic Archbishop Elias Chacour and Archbishop Boutros Mouallem, who were prevented from leaving Jerusalem to attend an interfaith meeting in London.[72]

See also

|

|

References

- ^ anti-catholicism. Dictionary.com. WordNet® 3.0. Princeton University. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/anti-catholicism (accessed: November 13, 2008).

- ^ Edwards, Jr., Mark. Apocalypticism Explained: Martin Luther, PBS.org.

- ^ Edward Gibbon (1994 edition edited by David Womersley) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Penguin Books: Vol 1, 469

- ^ The Gordon Riots

- ^ Felix Barker and Peter Jackson (1974) London: 2000 Years of a City and its People: 308. Macmillan: London

- ^ Fiancée of British royal abandons Catholicism to preserve succession http://www.catholicnewsagency.com/new.php?n=12525

- ^ [http://www.iol.ie/~fagann/1798/orange.htm THE MEN OF NO POPERY THE ORIGINS OF THE ORANGE ORDER]

- ^ From The formation of the Orange Order in The Orange Order from the Evangelical Truth website

- ^ THE RISE OF THE DEFENDERS 1793-5

- ^ Liz Curtis (1994) The Cause of Ireland: From United Irishmen to Partition: 37

- ^ Scotland On Sunday: November 2006: "Football rivalry boosts religious orders"

- ^ Jenkins, Philip (1 April 2003). The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-19-515480-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature.

- ^ "The Coming Catholic Church". By David Gibson. HarperCollins: Published 2004.

- ^ Annotation

- ^ Bilhartz, Terry D. Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University

Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-838-63227-0.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 31 (help) - ^ Jimmy Akin (2001-03-01). "The History of Anti-Catholicism". This Rock. Catholic Answers. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ a b The Bible Tells Me So: Uses and Abuses of Holy Scripture, Jim Hill and Rand Cheadle, 1996, Anchor Books/Doubleday, p. 82-85

- ^ Foster, J. R. (1 February 1988). The Third Republic from Its Origins to the Great War, 1871-1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-521-35857-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Larkin, Church and State after the Dreyfus Affair, pp. 138-41: `Freemasonry in France’, Austral Light 6, 1905, pp. 164-72, 241-50.

- ^ a b c Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- ^ Mark Almond (1996) Revolution: 500 Years of Struggle For Change: 136-7

- ^ Barbara A. Tenenbaum and Georgette M. Dorn (eds.), Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture (New York: Scribner's, 1996).

- ^ Stan Ridgeway, "Monoculture, Monopoly, and the Mexican Revolution" Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos 17.1 (Winter, 2001): 143.

- ^ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791-1899 p. 33 (2003 Brassey's) ISBN 1574884522

- ^ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p.393 (1993 W. W. Norton & Company) ISBN 0393310663

- ^ de la Cueva, Julio "Religious Persecution, Anticlerical Tradition and Revolution: On Atrocities against the Clergy during the Spanish Civil War" Journal of Contemporary History Vol.33(3) p. 355

- ^ New Evangelization with the Saints, L'Osservatore Romano 28 November 2001, page 3(Weekly English Edition)

- ^ Tucson priests one step away from sainthood Arizona Star 06.12.2007

- ^ Williford, Thomas J. Armando los espiritus: Political Rhetoric in Colombia on the Eve of La Violencia, 1930-1945 p.217-278 (Vanderbilt University 2005)

- ^ Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History Robert D. Kaplan Chapter 1 "Just so they could go to Heaven" pgs 3-28 ISBN-10: 0679749810 ISBN-13: 978-0679749813

- ^ Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History Robert D. Kaplan Chapter 1 "Just so they could go to Heaven" pgs 3-28 ISBN-10: 0679749810 ISBN-13: 978-0679749813

- ^ Patrick R O'Malley (2006) Catholicism, sexual deviance, and Victorian Gothic culture. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Franchot, Jenny (1994). "Two Escaped Nuns: Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk". Roads to Rome: The Antebellum Protestant Encounter with Catholicism. Berkeley, California (USA): The University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07818-7.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature.

- ^ Franchot, Jenny (1994). "Two Escaped Nuns: Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk", Roads to Rome: The Antebellum Protestant Encounter with Catholicism. Berkeley, California (USA): The University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07818-7

- ^ Mannard, Joseph G. (1981). American Anti-Catholicism and its Literature.

- ^ Convent Erotica

- ^ John Baxter (1994) Buñuel. London: Fouth Estate.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. p. 167.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard. The God Delusion. p. 317.

- ^ National Secular Society - Forget the “Da Vinci Code”: this is the book that tells the bombshell truth about the Catholic Church

- ^ An outbreak of anti-popery

- ^ "The Last Acceptable Prejudice".

- ^ Cottonian MSS quoted in Alan Ivimey (nd) A History of London: 113

- ^ R.W Dixon History of the Church of England quoted in Alan Ivimey (nd) A History of London: 112

- ^ The Buggery Act

- ^ Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes (HarperPress, 2006)

- ^ Evans, Richard J. "The Third Reich in Power" ISBN 0-713-99649-8 page 244-245

- ^ http://www.prefectpress.com

- ^ Philip Jenkins, Pedophiles and Priests: Anatomy of a Contemporary Crisis (Oxford University Press, 2001). ISBN 0-19-514597-6

- ^ "No You Don't, Mr. Pope!": A Brief History of Anti-Catholicism in America, A Three Part Series Offered by the Saint Francis University's Catholic Studies at a Distance Program Delivered by Arthur Remillard, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies. Saint Francis University CERMUSA website, retrieved May 2007

- ^ Herberg, Will. "Religion in a Secularized Society: Some Aspects of America's Three-Religion Pluralism", Review of Religious Research, vol. 4 no. 1, Autumn, 1962, p. 37

- ^ http://poll.gallup.com/content/?ci=22783

- ^ http://www.galluppoll.com/content/default.aspx?ci=24385&pg=2

- ^ 300 Fault O'Connor Role On AIDS Commission

- ^ a b c d e "The Last Acceptable Prejudice". America The National Catholic Weekly. 2000-03-25. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

- ^ The Last Acceptable Prejudice

- ^ bill donahue

- ^ Steven Roud (2006) The English Year. London, Penguin: 455-63

- ^ Lewes Bonfire Council, More Information on Bonfire, Accessed 3 December 2007

- ^ a b c Kelbie, Paul (2006-09-28). "The Big Question: In 2006, are Catholics really being discriminated against in Scotland?". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

- ^ a b Barnes, Eddie (2008-09-14). "The Shame Game". Scotland on Sunday. Johnston Press Digital Publishing. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chapter Three: Findings". Use of Section 74 of the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003 - Religiously Aggravated Reported Crime: An 18 Month Review. HMSO. 2006. Retrieved 2008-09-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "UVFs catalogue of atrocities". BBC.com, 3 May, 2007. Retrieved 8 November, 2007

- ^ Martin Dillon (1999 - second edition) The Shankill Butchers

- ^ English, Richard (2003). Armed Struggle: The History of the IRA. Pan Books. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-330-49388-4.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique (2005-03-11). "We are not afraid". Politics-Special Reports. The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- ^ Khalidi, Walid (1992). "All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948.". IPS. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- ^ Gruber, Ruth (August 14, 1998). "Israel Opposes Vatican Choice of Palestinian Archbishop". The Jewish News Weekly.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Vatican Rebukes Israel Over Comments On Palestinian Bishop ". Catholic World News. August 7, 1998.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Solheim, James (October 23, 2002). "Christian Leaders from Jerusalem Blocked From Attending Interfaith Meeting in London". Episcopal News Service.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Additional reading

- Anbinder; Tyler Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s 1992

- Bennett; David H. The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History University of North Carolina Press, 1988

- Billingon, Ray. The Protestant Crusade, 1830-1860 (1938)

- Blanshard; Paul.American Freedom and Catholic Power Beacon Press, 1949

- Thomas M. Brown, "The Image of the Beast: Anti-Papal Rhetoric in Colonial America", in Richard O. Curry and Thomas M. Brown, eds., Conspiracy: The Fear of Subversion in American History (1972), 1-20.

- Steve Bruce, No Pope of Rome: Anti-Catholicism in Modern Scotland (Edinburgh, 1985).

- Elias Chacour: "Blood Brothers. A Palestinian Struggles for Reconciliation in the Middle East" ISBN 0-8007-9321-8 with Hazard, David, and Baker III, James A., Secretary (Foreword by) 2nd Expanded ed. 2003. (Archbishop of Galilee, born in Kafr Bir'im, the book covers his childhood growing up in the town. (The first six chapters of Blood Brothers can be downloaded here (the November 08, 2005 link).

- Robin Clifton, "Popular Fear of Catholics during the English Revolution", Past and Present, 52 ( 1971), 23-55.

- Cogliano; Francis D. No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England Greenwood Press, 1995

- David Brion Davis, "Some Themes of Counter-subversion: An Analysis of Anti-Masonic, Anti-Catholic and Anti-Mormon Literature", Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 47 (1960), 205-224.

- Andrew M. Greeley, An Ugly Little Secret: Anti-Catholicism in North America 1977.

- Henry, David. "Senator John F. Kennedy Encounters the Religious Question: I Am Not the Catholic Candidate for President." Contemporary American Public Discourse. Ed. H. R. Ryan. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., 1992. 177-193.

- Higham; John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925 1955

- Hinckley, Ted C. "American Anti-catholicism During the Mexican War" Pacific Historical Review 1962 31(2): 121-137. ISSN 0030-8684

- Hostetler; Michael J. "Gov. Al Smith Confronts the Catholic Question: The Rhetorical Legacy of the 1928 Campaign" Communication Quarterly. Volume: 46. Issue: 1. 1998. Page Number: 12+.

- Philip Jenkins, The New Anti-Catholicism: The Last Acceptable Prejudice (Oxford University Press, New ed. 2004). ISBN 0-19-517604-9

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (1971)

- Jensen, Richard. "'No Irish Need Apply': A Myth of Victimization," Journal of Social History 36.2 (2002) 405-429, with illustrations

- Karl Keating, Catholicism and Fundamentalism — The Attack on "Romanism" by "Bible Christians" (Ignatius Press, 1988). ISBN 0-89870-177-5

- Kenny; Stephen. "Prejudice That Rarely Utters Its Name: A Historiographical and Historical Reflection upon North American Anti-Catholicism." American Review of Canadian Studies. Volume: 32. Issue: 4. 2002. pp: 639+.

- Khalidi, Walid. "All that Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948." 1992. ISBN 0-88728-224-5.

- McGreevy, John T. "Thinking on One's Own: Catholicism in the American Intellectual Imagination, 1928-1960." The Journal of American History, 84 (1997): 97-131.

- J.R. Miller, "Anti-Catholic Thought in Victorian Canada" in Canadian Historical Review 65, no.4. (December 1985), p. 474+

- Moore; Edmund A. A Catholic Runs for President 1956.

- Moore; Leonard J. Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 University of North Carolina Press, 1991

- E. R. Norman, Anti-Catholicism in Victorian England (1968).

- D. G. Paz, "Popular Anti-Catholicism in England, 1850-1851", Albion 11 (1979), 331-359.

- Thiemann, Ronald F. Religion in Public Life Georgetown University Press, 1996.

- Carol Z. Wiener, "The Beleaguered Isle. A Study of Elizabethan and Early Jacobean Anti-Catholicism", Past and Present, 51 (1971), 27-62.

- Wills, Garry. Under God 1990.

- White, Theodore H. The Making of the President 1960 1961.