Herod the Great: Difference between revisions

m Reverting possible vandalism by 125.254.34.194 to version by Jackfork. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot. (625087) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

In the story, Herod was advised by the assembled chief priests and scribes of the people that the Prophet had written that the "Anointed One" (Greek: ''ho christos'') was to be born in [[Bethlehem|Bethlehem of Judea]]. Herod therefore sent the Magi to Bethlehem, instructing them to search for the child and, after they had found him, to "report to me, so that I too may go and worship him". However, after they had found Jesus, the Magi were warned in a dream not to report back to Herod. Similarly, [[Saint Joseph|Joseph]] was warned in a dream that Herod intended to kill Jesus, so he and his family fled to Egypt. When Herod realized he had been outwitted by the Magi, he gave orders to kill all boys of the age of two and under in Bethlehem and its vicinity. Joseph and his family stayed in Egypt until Herod's death, then moved to [[Nazareth]] in Galilee in order to avoid living under Herod's son Archelaus. |

In the story, Herod was advised by the assembled chief priests and scribes of the people that the Prophet had written that the "Anointed One" (Greek: ''ho christos'') was to be born in [[Bethlehem|Bethlehem of Judea]]. Herod therefore sent the Magi to Bethlehem, instructing them to search for the child and, after they had found him, to "report to me, so that I too may go and worship him". However, after they had found Jesus, the Magi were warned in a dream not to report back to Herod. Similarly, [[Saint Joseph|Joseph]] was warned in a dream that Herod intended to kill Jesus, so he and his family fled to Egypt. When Herod realized he had been outwitted by the Magi, he gave orders to kill all boys of the age of two and under in Bethlehem and its vicinity. Joseph and his family stayed in Egypt until Herod's death, then moved to [[Nazareth]] in Galilee in order to avoid living under Herod's son Archelaus. |

||

The [[Massacre of the Innocents#Historicity|historical accuracy]] of this event has been questioned, since although Herod was certainly guilty of many brutal acts, including the killing of his wife and two of his sons, no other source from the period makes any reference to such a massacre.<ref>[[E. P. Sanders]], ''The Historical Figure of Jesus'', pp. 87-88.</ref> |

The [[Massacre of the Innocents#Historicity|historical accuracy]] of this event has been questioned, since although Herod was certainly guilty of many brutal acts, including the killing of his wife and two of his sons, no other source from the period makes any reference to such a massacre.<ref>[[E. P. Sanders]], ''The Historical Figure of Jesus'', pp. 87-88.</ref> Rather, the New Testament account of Herod killing these children is meant to reflect the story of Moses as a [[typology]] for Jesus.<ref>http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/matthew/matthew2.htm#foot6</ref> |

||

==Death== |

==Death== |

||

Revision as of 08:10, 6 March 2009

Herod (Hebrew: הוֹרְדוֹס Horodos, Greek: Ἡρῴδης Hērōdēs), also known as Herod I or Herod the Great (73 BC – 4 BC in Jericho), was a Roman client king of Israel.[1] Herod is known for his colossal building projects in Jerusalem and other parts of the ancient world, including the rebuilding of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, sometimes referred to as Herod's Temple. Some details of his biography can be gleaned from the works of the 1st century AD Roman-Jewish historian Josephus Flavius.

In Christian scripture, Biblical belief has Herod perpetrating the Massacre of the Innocents, described in Chapter 2 of the Gospel according to Matthew.[2] However, no historical extra-biblical source exists supporting this claim of such a decree by Herod or any ruler of the time.[3]

Biography

Herod was born around 74 BC. He was the second son of Antipater the Idumaean, a high-ranked official under Ethnarch Hyrcanus II, and Cypros, a Nabatean.[4] A loyal supporter of Hyrcanus II, Antipater appointed Herod governor of Galilee at 25, and his older brother, Phasael, governor of Jerusalem. He enjoyed the backing of Rome but his excessive brutality was condemned by the Sanhedrin.

In 43 BC, following the chaos caused by Antipater offering financial support to Caesar's murderers, Antipater was poisoned. Herod, backed by the Roman Army, executed his father's murderer. Afterwards, Antigonus, Hyrcanus' nephew, tried to take the throne from his uncle. Herod defeated him and then married his teenage niece, Mariamne (known as Mariamne I), which helped to secure him a claim to the throne and gain some Jewish favor. However, Herod already had a wife, Doris, and a three-year-old son, Antipater III, and chose to banish Doris and her child.

In 42 BC, he convinced Mark Antony and Octavian that his father had been forced to help Caesar's murderers. Herod was then named tetrarch of Galilee by the Romans. However, since Herod's family had converted to Judaism under duress, his Jewishness had come into question by some elements of Judean society.[citation needed] The Idumaean family, successors to the Edomites of the Hebrew Bible, settled in Idumea (Biblical Edom), in southern Israel. When the Maccabean John Hyrcanus conquered Idumea in 140–130 BC, he required all Idumaeans to obey Jewish law or to leave; most Idumaeans thus converted to Judaism. While King Herod publicly identified himself as a Jew and was considered as such by some,[5] this religious identification notwithstanding was undermined by the Hellenistic cultural affinity of the Herodians, which would have earned them the antipathy of observant Jews.[6]

In 40 BC Antigonus tried to take the throne again with the help of the Parthians, this time succeeding. Herod fled to Rome to plead with the Romans to restore him to power. There he was elected "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate.[7] In 37 BC the Romans fully secured Israel and executed Antigonus. Herod took the role as sole ruler of Israel and took the title of basileus (Gr. Βασιλευς) for himself, ushering in the Herodian Dynasty and ending the Hasmonean Dynasty. He ruled for 34 years.

Architectural achievements

- Main article: Herodian architecture

Herod's most famous and ambitious project was the expansion of the Second Temple in Jerusalem.

In the eighteenth year of his reign (20–19 BC), Herod rebuilt the Temple on "a more magnificent scale".[8] The new Temple was finished in a year and a half, although work on out-buildings and courts continued another eighty years.[8] To comply with religious law, Herod employed 1,000 priests as masons and carpenters in the rebuilding.[8] The finished temple, which was destroyed in 70 AD, is sometimes referred to as Herod's Temple. The Wailing Wall or Western Wall in Jerusalem is currently the only visible section of the four retaining walls built by Herod, creating a flat platform (the Temple Mount) upon which the Temple was then constructed.

Some of Herod's other achievements include the development of water supplies for Jerusalem, building fortresses such as Masada and Herodium, and founding new cities such as Caesarea Maritima and the enclosures of Cave of the Patriarchs and Mamre in Hebron. He and Cleopatra owned a monopoly over the extraction of asphalt from the Dead Sea, which was used in ship building. He leased copper mines on Cyprus from the Roman emperor.

Discovery of quarry

On September 25, 2007, Yuval Baruch, archaeologist with the Israeli Antiquities Authority announced their discovery of a quarry compound which provided King Herod with the stones to renovate the second Temple. It houses the Temple Mount. Coins, pottery and iron stake found proved the date of the quarrying to be about 19 BC. Archaeologist Ehud Netzer confirmed that the large outlines of the stone cuts is evidence that it was a massive public project worked on by hundreds of slaves.[9]

New Testament references

Herod the Great appears in ancient Christian scriptures, in the Gospel according to Matthew (Ch. 2), which describes an event known as the Massacre of the Innocents. No historical extra-biblical source exists supporting this claim of such a decree by Herod, or any ruler of the time.[3]

According to Matthew, shortly after the birth of Jesus, Magi from the East visited Herod to inquire the whereabouts of "the one having been born king of the Jews", because they had seen his star in the east and therefore wanted to pay him homage. Herod, who was himself King of Judea, was alarmed at the prospect of the newborn king usurping his rule.

In the story, Herod was advised by the assembled chief priests and scribes of the people that the Prophet had written that the "Anointed One" (Greek: ho christos) was to be born in Bethlehem of Judea. Herod therefore sent the Magi to Bethlehem, instructing them to search for the child and, after they had found him, to "report to me, so that I too may go and worship him". However, after they had found Jesus, the Magi were warned in a dream not to report back to Herod. Similarly, Joseph was warned in a dream that Herod intended to kill Jesus, so he and his family fled to Egypt. When Herod realized he had been outwitted by the Magi, he gave orders to kill all boys of the age of two and under in Bethlehem and its vicinity. Joseph and his family stayed in Egypt until Herod's death, then moved to Nazareth in Galilee in order to avoid living under Herod's son Archelaus.

The historical accuracy of this event has been questioned, since although Herod was certainly guilty of many brutal acts, including the killing of his wife and two of his sons, no other source from the period makes any reference to such a massacre.[10] Rather, the New Testament account of Herod killing these children is meant to reflect the story of Moses as a typology for Jesus.[11]

Death

The scholarly consensus, based on Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews is that Herod died at the end of March or early April in 4 BC. Josephus wrote that Herod died 37 years after being named as King by the Romans, and 34 years after the death of Antigonus.[12] This would imply that he died in 4 BC. This is confirmed by the fact that his three sons, between whom his kingdom was divided, dated their rule from 4 BC. For instance, he states that Herod Philip II's death took place after a 37-year reign in the 20th year of Tiberius, which would imply that he took over on Herod's death in 4 BC.[13] In addition, Josephus wrote that Herod died after a lunar eclipse,[14] and a partial eclipse[15] took place in 4 BC. It has been suggested that 5 BC might be a more likely date[16]– there were two total eclipses in that year.[17][18] However, the 4 B.C. date is almost universally accepted.[19][20]

Josephus wrote that Herod's final illness – sometimes named as "Herod's Evil"[21] – was excruciating (Ant. 17.6.5). From Josephus' descriptions, some medical experts propose that Herod had chronic kidney disease complicated by Fournier's gangrene.[22] Modern scholars agree he suffered throughout his lifetime from depression and paranoia.[23] More recently, others report that the visible worms and putrefaction described in his final days are likely to have been scabies. This can explain his death, but can also account for his psychiatric symptoms.[24] Similar symptoms attended the death of his grandson Herod Agrippa in AD 44.

Josephus also stated that Herod was so concerned that no one would mourn his death, that he gave orders to have distinguished men killed at the time of his death so that the displays of grief that he craved would take place.

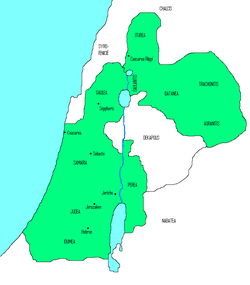

After Herod's death, his kingdom was divided among three of his sons, namely Herod Archelaus, Herod Antipas, and Herod Philip II, who ruled as tetrarchs rather than kings.

Tomb discovery

The location of Herod's tomb is documented by Roman historian Flavius Josephus, who writes, "And the body was carried two hundred furlongs, to Herodium, where he had given order to be buried."[25]

Flavius Josephus provides more clues about Herod's tomb which he calls Herod's monuments:

So they threw down all the hedges and walls which the inhabitants had made about their gardens and groves of trees, and cut down all the fruit trees that lay between them and the wall of the city, and filled up all the hollow places and the chasms, and demolished the rocky precipices with iron instruments; and thereby made all the place level from Scopus to Herod's monuments, which adjoined to the pool called the Serpent's Pool.[26]

Professor Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from Hebrew University, read the writings of Josephus and focused his search on the vicinity of the pool and its surroundings at the Winter Palace of Herod in the Judean desert. An article of the New York Times states,

Lower Herodium consists of the remains of a large palace, a race track, service quarters, and a monumental building whose function is still a mystery. Perhaps, says Ehud Netzer, who excavated the site, it is Herod's mausoleum. Next to it is a pool, almost twice as large as modern Olympic-size pools.[27]

It took 35 years for Netzer to identify the exact location, but on May 7, 2007, an Israeli team of archaeologists of the Hebrew University led by Netzer, announced they had discovered the tomb.[28][29][30][31][32] The site is located at the exact location given by Flavius Josephus, atop of tunnels and water pools, at a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to Herodium, 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) south of Jerusalem.[33]

Chronology

30s BC

- 39–37 BC– War against Antigonus. After the conquest of Jerusalem and victory over Antigonus, Mark Antony executes Antigonus.

- 36 BC– Herod makes his 17-year-old brother-in-law, Aristobulus III of Judea, high priest, fearing that the Jews would appoint Aristobulus III of Judea "king of the Jews" in his place.

- 35 BC– Aristobulus III of Judea is drowned at a party, on Herod's orders.

- 32 BC– The war against Nabatea begins, with victory one year later.

- 31 BC– Judea suffers a devastating earthquake. Octavian defeats Mark Antony, so Herod switches allegiance to Octavian, later known as Augustus.

- 30 BC– Herod is shown great favour by Octavian, who at Rhodes confirms him as King of Judaea.

20s BC

- 29 BC– Josephus writes that Herod had great passion and also great jealousy concerning his wife, Mariamne I. She learns of Herod's plans to murder her, and stops sleeping with him. Herod puts her on trial on a charge of adultery. His sister, Salome I, was chief witness against her. Mariamne I's mother Alexandra made an appearance and incriminated her own daughter. Historians say her mother was next on Herod's list to be executed and did this only to save her own life. Mariamne was executed, and Alexandra declared herself Queen, stating that Herod was mentally unfit to serve. Josephus wrote that this was Alexandra's strategic mistake; Herod executed her without trial.

- 28 BC– Herod executed his brother-in-law Kostobar[34] (husband of Salome, father to Berenice) for conspiracy. Large festival in Jerusalem, as Herod had built a Theatre and an Amphitheatre.

- 27 BC– An assassination attempt on Herod was foiled. To honor Augustus, Herod rebuilt Samaria and renamed it Sebaste.

- 25 BC– Herod imported grain from Egypt and started an aid program to combat the widespread hunger and disease that followed a massive drought. He also waives a third of the taxes.

- 23 BC– Herod built a palace in Jerusalem and the fortress Herodion (Herodium) in Judea. He married his third wife, Mariamne II, the daughter of high priest Simon.[35]

- 22 BC– Herod began construction on Caesarea Maritima and its harbor. The Roman emperor Augustus grants him the regions Trachonitis, Batanaea and Auranitis to the north-east of Judea.

- Circa 20 BC– Expansion started on the Second Temple. (See Herod's Temple)

10s BC

- Circa 18 BC– Herod traveled for the second time to Rome.

- 14 BC– Herod supported the Jews in Anatolia and Cyrene. Owing to the prosperity in Judaea he waived a quarter of the taxes.

- 13 BC– Herod made his first-born son Antipater (his son by Doris) first heir in his will.

- 12 BC– Herod suspected both his sons (from his marriage to Mariamne I) Alexander and Aristobulus of threatening his life. He took them to Aquileia to be tried. Augustus reconciled the three. Herod supported the financially strapped Olympic Games and ensured their future. Herod amended his will so that Alexander and Aristobulus rose in the royal succession, but Antipater would be higher in the succession.

- Circa 10 BC– The newly expanded temple in Jerusalem was inaugurated. War against the Nabateans began.

0s BC

- 9 BC– Caesarea Maritima was inaugurated. Owing to the course of the war against the Nabateans, Herod fell into disgrace with Augustus. Herod again suspected Alexander of plotting to kill him.

- 8 BC– Herod accused his sons by Mariamne I of high treason. Herod reconciled with Augustus, which also gave him the permission to proceed legally against his sons.

- 7 BC– The court hearing took place in Berytos (Beirut) before a Roman court. Mariamne I's sons were found guilty and executed. The succession changed so that Antipater was the exclusive successor to the throne. In second place the succession incorporated (Herod) Philip, his son by Mariamne II.

- 6 BC– Herod proceeded against the Pharisees.

- 5 BC– Antipater was brought before the court charged with the intended murder of Herod. Herod, by now seriously ill, named his son (Herod) Antipas (from his fourth marriage with Malthace) as his successor.

- 4 BC– Young disciples smashed the golden eagle over the main entrance of the Temple of Jerusalem after the Pharisee teachers claimed it was an idolatrous Roman symbol. Herod arrested them, brought them to court, and sentenced them. Augustus approved the death penalty for Antipater. Herod then executed his son, and again changed his will: Archelaus (from the marriage with Malthace) would rule as king over Herod's entire kingdom, while Antipas (by Malthace) and Philip (from the fifth marriage with Cleopatra of Jerusalem) would rule as Tetrarchs over Galilee and Peraea (Transjordan), also over Gaulanitis (Golan), Trachonitis (Hebrew: Argob), Batanaea (now Ard-el-Bathanyeh) and Panias. As Augustus did not confirm his will, no one got the title of King; however, the three sons did get the stated territories.

Marriages and children

| Wife | Children |

|---|---|

| Doris |

|

| Mariamne I, daughter of Hasmonean Alexandros |

|

| Mariamne II, daughter of High-Priest Simon |

|

| Malthace |

|

| Cleopatra of Jerusalem |

|

| Pallas |

|

| Phaidra |

|

| Elpis |

|

| A cousin (name unknown) |

|

| A niece (name unknown) |

|

It is very probable that Herod had more children, especially with the last wives, and also that he had more daughters, as female births at that time were often not recorded.[citation needed]

Family trees

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (March 2008) |

Marriages and descendants

Herod the Great + Doris | Antipater d. 4 BC?

Herod the Great + Mariamne I, d. 29 BC?, dt. of Alexandros. | ————————————————————————————————————————————— | | | | Aristobulus Alexander Salampsio + Phasael Cypros d. 7 BC? d. 7 BC? | m. Antipater(2) m. Berenice Cypros | ———————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————— | | | | | Mariamne III Herod III Herodias Herod Agrippa Aristobulus V m. her uncle King of Chalcis + King of Judea Archelaus ? m. 1. Herod II Boethus her uncle 2. Herod Antipas her uncle

Herod the Great + Mariamne II, dt. of Simon the High-Priest. | Herod II Boethus

Herod the Great + Malthace (a Samaritan) | ———————————————————————————————————————————————— | | | Herod Antipas Archelaus Olympias b. 20 BC? + Phasaelis, dt. of Aretas IV, king of Arabia "divorced" to marry: + Herodias, dt. of Aristobulus (son of Herod the Great)

Herod the Great + Cleopatra of Jerusalem | Philip the Tetrarch d. AD 34

- Notes.

- Antipater(2) was the son of Joseph and Salome

- Dates with ? need verifying against modern findings

Ancestors

Antipater the Idumaean + Cypros, Arab princess from Petra, Jordan in Nabatea. | ————————————————————————————————————————————— | | | | | Phasael Herod the Great Joseph Pheroras Salome I (74-4 BC)

| Sign & Meaning |

|---|

| + = married |

| | = descended from |

| ../——— = sibling |

| dt. = daughter |

| b. = born |

| d. = died |

| m. = was married to |

| ? = not included here or unknown |

Alexandros + Alexandra

|

———————————————————————————————————

| |

Aristobulus III of Judea Mariamne, dt.

(d. 35 BC) m. Herod the Great

(last Hasmonean scion;

appointed high priest; drowned)

Herod in later culture

References

- ^

"Herod". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

born 74 BC died March/April, 4 BC, Jericho, Judaea byname Herod the Great, Latin Herodes Magnus Roman-appointed king of Judaea ... his father, Antipater, was an Edomite (an Arab from the region between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba)

- ^ MATTHEW 2:16 "When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi." 'HOLY' Bible, New International Version (Eng. Bible-NIV095-00301 ABS-1986-20,000-Z-1)

- ^ a b Paine, Thomas (1819). The Political and Miscellaneous Works of Thomas Paine. London: R. Carlile. pp. 59–61.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Paine" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Herod I". Encyclopaedia Judaica. (CD-ROM Edition Version 1.0). Ed. Cecil Roth. Keter Publishing House. ISBN 965-07-0665-8

- ^ Flavius Josephus, The Jewish War, Book 2, Chapter 13, "There was also another disturbance at Caesarea, - those Jews who were mixed with the Syrians that lived there rising a tumult against them. The Jews pretended that the city was theirs, and said that he who built it was a Jew, meaning King Herod. The Syrians confessed also that its builder was a Jew; but they still said, however, that the city was a Grecian city; for that he who set up statues and temples in it could not design it for Jews."

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia: Herod I: Opposition of the Pious: "All the worldly pomp and splendor which made Herod popular among the pagans, however, rendered him abhorrent to the Jews, who could not forgive him for insulting their religious feelings by forcing upon them heathen games and combats with wild animals …"

- ^ Jewish War 1.14.4: Mark Antony " …then resolved to get him made king of the Jews… told them that it was for their advantage in the Parthian war that Herod should be king; so they all gave their votes for it. And when the senate was separated, Antony and Caesar went out, with Herod between them; while the consul and the rest of the magistrates went before them, in order to offer sacrifices [to the Roman gods], and to lay the decree in the Capitol. Antony also made a feast for Herod on the first day of his reign;"

- ^ a b c Temple of Herod, Jewish Encyclopedia

- ^ Yahoo.com, Report: Herod's Temple quarry found

- ^ E. P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus, pp. 87-88.

- ^ http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/matthew/matthew2.htm#foot6

- ^ Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Book 17, Chapter 8

- ^ Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, Book 18, Chapter 4

- ^ (Flavius Josephus, Jewish Antiquities, 17.167)

- ^ NASA catalog, only 37 % of the moon was in shadow

- ^ Timothy David Barnes, “The Date of Herod’s Death,” Journal of Theological Studies ns 19 (1968), 204-19

- ^ http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/LEcat/LE-0099-0000.html NASA lunar eclipse catalog

- ^ W. E. Filmer, “Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great,” Journal of Theological Studies ns 17 (1966), 283-98

- ^ P. M. Bernegger, “Affirmation of Herod’s Death in 4 B.C.,” Journal of Theological Studies ns 34 (1983), 526-31.

- ^ For a recent argument that Herod died in 1 B.C., see Steinmann, Andrew, "When Did Herod the Great Reign?", Novum Testamentum, Volume 51, Number 1, 2009 , pp. 1-29(29)

- ^ What loathsome disease did King Herod die of?, The Straight Dope, November 23, 1979

- ^ CNN Archives, 2002

- ^ http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/876330.htm

- ^ Ashrafian H. Herod the Great and his worms. J Infect. 2005 Jul;51(1):82-3.

- ^ Flavius Josephus. The Wars of the Jews or History of the Destruction of Jerusalem. Book V. Chapter 33.1

- ^ Flavius Josephus. The Wars of the Jews or History of the Destruction of Jerusalem. Book V. Chapter 3.2

- ^ Nitza Rosovsky. Discovering Herod's Israel. The New York Times. April 24, 1983

- ^ Hebrew University: Herod's tomb and grave found at Herodium http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/856784.html

- ^ "Israeli Archaeologist Finds Tomb of King Herod", FOX News, 7 May 2007

- ^ "King Herod's tomb unearthed, Israeli university claims", CNN, 7 May 2007

- ^ Herod's Tomb Discovered IsraCast, May 8, 2007.

- ^ "Herod's tomb reportedly found inside his desert palace" The Boston Globe, May 8, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Archaeologists Find Tomb of King Herod. The New York Times, May 9, 2007, http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/world/AP-Israel-Herods-Tomb.html

- ^ Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XV, Chapter 7.8

- ^ Flavius Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XV, Chapter 9.3

Further reading

- Zeitlin, Solomon (1967). The Rise and Fall of the Judean State. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society. Library of Congress Catalog Number 61-11708.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|accessyear=,|origmonth=,|accessmonth=,|month=,|chapterurl=,|origdate=, and|coauthors=(help) - Duane W. Roller, The Building Program of Herod the Great(Berkeley, 1998).

- Robert Gree, Herod the Great

- Michael Grant, Herod the Great

- Adam Kolman Marshak, "The dated coins of Herod the great: Towards a new chronology," Journal for the Study of Judaism, 37,2 (2006), 212-240.

- Linda-Marie Guenther (ed.), Herodes und Rom (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007), Pp. 121.

- by Aryeh Kasher, King Herod: A Persecuted Persecutor: A Case Study in Psychohistory and Psychobiography (Berlin and New York, Walter de Gruyter, 2007), pp. 514.

- Kokkinos, Nikos (ed.), The World of the Herods. Volume 1 of the International Conference The World of the Herods and the Nabataeans held at the British Museum, 17-19 April 2001 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2007), Pp. 327 (Oriens et Occidens, 14).

External links

- Resources > Second Temple and Talmudic Era > Herod and the Herodian Dynasty The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Tomb Found

- Halachic Status of Herod

- Herod's Tomb -images

- Magen Broshi, A King on the Shrink's Couch, review of "King Herod: A Persecuted Persecutor

- Family trees

- extract Britanicca Vol 5 page 879

- Encyclopedia.com

- Outline of Great Books Volume I - King Herod: extracts from the works of Josephus

- Timeline 49 to 1 BC

- Herod surnamed the Great in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Herod I

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Herod

- The Horrors of Herod

- Benny Ziffer: In the enlightened world it's called robbery

- King Herod the Great

- King Herod's Tomb Found Biblical Archaeology Review