Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science: Difference between revisions

edited by robot: archiving February 4 |

|||

| Line 262: | Line 262: | ||

= February 7 = |

= February 7 = |

||

== How big will sun be at first RGB in 5 billion years? == |

|||

2008 studies show [http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008MNRAS.386..155S Earth will be swallow up] because of the tidal interaction. Without considering loss of sun's mass/gravity to make it expand orbit, how big will sun be at first RGB in 5 billion years? is it roughly size of earth orbit little less than 1 AU or greatly than 1 AU. is it less than 200 solar radius or is is 250 solar radius? Does sun shrink between first and second RGB? My astronomy teacher display sun shrinks after first RGB then expands again at second RGB? How much will sun shrink between first and second RGB? about the size today or less than sun's size today. Becuase second RGB is 1.2 AU, or 260 solar radius. The article didn't mention the first RGB.--[[Special:Contributions/69.229.39.25|69.229.39.25]] ([[User talk:69.229.39.25|talk]]) 00:37, 7 February 2012 (UTC) |

|||

Revision as of 00:37, 7 February 2012

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

February 3

How to use Hertzsprung–Russell diagram?

Let say there is a star i have to identify it on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. How can i identify it base on its apparent magnitude (in other word its brightness)? Basically i need someone to explain for me how to use the diagram and how to interpret it. Ok i have an example problem, i already know the correct answers but i don't understand them. Where would Mira variable be locate on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram? The answer is V. I was given the Mira variable's brightness. Pendragon5 (talk) 01:05, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- You are going to have to convert it to an absolute magnitude by adjusting based on the distance. A Mira variable should move around a bit depending on its brightness cycle, so one point would not be enough. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 08:56, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Yea that's what i don't really get. There are many things around the HR diagram to determine where the star should be on there but they only give me like 1 info. Let say they do give me the absolute magnitude then how do i do it? The answer was V so i would guess all they want is just a basic answer. This letter V would represent something on the HR diagram which i don't know.Pendragon5 (talk) 12:43, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- If you look at the big picture at the top of that article, you'll see that V refers to the main sequence (if that's the only answer they gave, then they must be asking you for just the general category of star, rather than anything more detailed). You'll also see that the different categories only overlap between about -3 and +5 in absolute magnitude (although dimmer than +10 could be a white dwarf, if you are counting those). If the absolute magnitude you are given is outside that range, then you can be pretty sure about which group it will fall into. If it's in that range, then you need more information (firstly, colour, but if it's blue-white you would need to know its size to distinguish between a giant, sub-giant or main sequence star). --Tango (talk) 13:12, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- What is the colour (B-V) at the bottom of the diagram represent?Pendragon5 (talk) 20:34, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- That's the B-V colour. It is one of the measures of color that can be extracted under the UBV photometric system. To measure the B-V color, one photographs a star through a B (blue) filter, and again through a V (visible, actually a slightly yellowish green) filter. The B-V color is the difference in apparent magnitude when seen through the B and V filters. If the star's light output is more blue (smaller B magnitude) the B-V value will be smaller (or even negative) and the star will fall further to the left on the HR diagram. If the star is more red (less blue, and therefore greater B magnitude), B-V will be more positive and the star will sit further to the right on the HR diagram. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 22:01, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- What is the colour (B-V) at the bottom of the diagram represent?Pendragon5 (talk) 20:34, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- If you look at the big picture at the top of that article, you'll see that V refers to the main sequence (if that's the only answer they gave, then they must be asking you for just the general category of star, rather than anything more detailed). You'll also see that the different categories only overlap between about -3 and +5 in absolute magnitude (although dimmer than +10 could be a white dwarf, if you are counting those). If the absolute magnitude you are given is outside that range, then you can be pretty sure about which group it will fall into. If it's in that range, then you need more information (firstly, colour, but if it's blue-white you would need to know its size to distinguish between a giant, sub-giant or main sequence star). --Tango (talk) 13:12, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Yea that's what i don't really get. There are many things around the HR diagram to determine where the star should be on there but they only give me like 1 info. Let say they do give me the absolute magnitude then how do i do it? The answer was V so i would guess all they want is just a basic answer. This letter V would represent something on the HR diagram which i don't know.Pendragon5 (talk) 12:43, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

Does decay heating and nuclear fission generate the same amount of energy in the end?

Suppose I have a certain amount of HEU and want to harvest the greatest amount of energy from it in the form of heat. There are two possible methods:

1. Decay heating over an infinitesimal amount of time.

2. Construct and detonate a fission bomb. (assuming all the uranium is consumed in the fission process and that the fissile products contain a negligible amount of untapped radioactivity energy)

Would the two methods generate the same amount of heat in the end? I'm guessing yes but I don't know enough about the subject matter to justify it.

And no, I'm not a terrorist. This is just a thought experiment to see whether it's feasible to use nuclear weapons to geologically reactivate Mars's core.99.245.35.136 (talk) 09:49, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- I think you'd have to explode something like a Hiroshima type bomb every ten minutes to equal the amount of heat generated in the Earth's core by fission. I think we'd have huge problems trying to do that even using fusion bombs never mind the problem of getting it near the centre. Plus I don't see the point. Dmcq (talk) 12:47, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- No, they wouldn't release the same energy because you won't end up with the same results. The decay products will, after a while, mostly end up as lead. The fissile products will be all sorts of things. Your problem is that the radioactivity of the fissile products isn't negligible to your calculation. If you include the decay heat from the fissile products, you should end up with approximately the same total energy because they will all decay into lead eventually as well. (It might not be exactly the same because there are different isotopes of lead they might decay into, and you may have to wait billions of years before they actually get to lead if they decay to something else stable first). The important thing is to compare what you have at the beginning with what you have at the end. If they are the same, then the energy released must be the same. However, I don't think your plan to heat up Mar's core would work - you would probably destroy most of the planet in the process, even if you could find enough fissile material to do it. --Tango (talk) 13:18, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Side note: "infinitesimal" means "very small", not "very large". --Sean 14:41, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- I wouldn't think it will be the same. From a thermodynamics point of view, a fission process would be irreversible adiabatic (nearly), while the decay process would probably be reversible isothermal (because it takes place quasi-statically). The reversible isothermal process would probably generate more energy. I have no background in Nuclear Physics, but only thermodynamics, so excuse any inconsistencies please. Lynch7 14:49, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- This should be pretty easy to quantify. The amount of energy released by an average U-235 fission is around 200 MeV. What's the energy released over the entire course of a U-235 decay chain? According to this chart, it's at most 46.4 MeV by the time it gets to lead. Comparing masses of them directly of course assumes 100% efficiency in the bomb. If my understanding is right, they would be equal if the bomb is only 23.2% efficient, and the decay would win out if the bomb was less efficient than that. The Little Boy bomb was around 1% efficient, the Fat Man bomb was about 17% efficient, but later bombs were much more efficient than either of those. (If I've made some sort of idiotic assumption or error, someone please correct me!) Again, this neglects fission products, which are pretty radioactive, and would tip the balance quite decisively in the direction of the bomb. --Mr.98 (talk) 19:14, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Out of curiosity, I ran through one set of common fission products, strontium-94 and xenon-140. They give off a total of about 24 MeV from their respective decay chains. So that's over half of the total energy from the total U-235 decay chain by itself, without even including the fission yield. --Mr.98 (talk) 21:09, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

is any encryption other than OTP physically secure

I mean in a physical-universe sense (including quantum mechanics or anything else that could be discovered). I don't consider "hey it would take a while to compute with the best-known current algorithms on the best-known current physical non-quantum mechanical computers". --78.92.81.13 (talk) 13:19, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- It depends. What do you mean by secure? Many algorithms are secure enough for any practical purpose. But, you seem to be asking in a hypothetical sense if an encryption could be completely secure under any theoretical circumstance. WKB52 (talk) 13:36, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- A one-time pad is unique in that, properly executed, cryptanalysis is not only practically but theoretically impossible (I think this is what you mean by "physically secure"). Cryptographer Bruce Schneier is fond of noting, though, that modern cryptographic methods are plenty secure, both now and for the foreseeable future, and that other factors (that tricky "properly executed" clause above) are far more likely to cause cryptographic failure -- even (or particularly) in the case of OTP. — Lomn 16:04, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The security of a OTP shouldn't be exaggerated - you have to get those numbers from somewhere. For example, you might use a random number generator which is easily reverse engineered. Or you can use a service like HotBits,[1] which I assume has its entire output archived to some handy-dandy NSA decoding disk somewhere in transit. More to the point, that sticker on your computer that says "Intel inside" isn't really talking about the brand of chip they used... Wnt (talk) 17:27, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Well, you could generate them from a physically random source (say, use diode noise to fill an entropy pool, and take out only as much entropy as you put in), and unless NSA has invented magic, it's hard to see how they could get at that. The difficulty, of course, is key exchange — somehow you have to get the same random values to both parties.

- But if you know in advance with whom you want to exchange secure messages, this can certainly be done. Just fill up some DVDs with the random bits, and transfer the DVDs in such a way that they never leave the physical custody of trusted parties. It's a lot less convenient than public-key methods, but it can be done. --Trovatore (talk) 17:37, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Are there actually any cases of people being able to crack modern, strong encryption schemes because of insufficient pseudorandomness? (I'm not counting cases like VENONA where they accidentally duplicated the same random number sheets more than once which was a lucky typo, not a case of the algorithm being wrong. I'm also not counting toy cases where people demonstrate how pseudorandomness can be misleading — I mean actual cases of intelligently designed systems with intelligently used pseudorandom or quasirandom number generators.) --Mr.98 (talk) 03:24, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think that's the question at issue. I think Wnt was assuming a one-time pad based on a PRNG, which as far as I know is not a commonly used encryption scheme, though in principle it should work given a sufficiently strong PRNG. The classical one-time pad is based on true randomness rather than a PRNG. --Trovatore (talk) 04:19, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- OK, but I just wonder if there's any evidence to support the idea that you can crack a code on the basis of its randomness not being "truly" random, assuming you are using a modern PRNG that isn't being implemented incorrectly. --Mr.98 (talk) 23:26, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I think it's worth adding that, in addition to the randomness (or lack thereof) issue raised above, the one-time pad also needs to be "as large as or greater than the plaintext, never reused in whole or part, and kept secret" (to quote our article) in order to be as impervious to cryptanalysis as Lomn initially suggested. Jwrosenzweig (talk) 06:55, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, Mr. 98 - see here: http://it.slashdot.org/story/08/05/13/1533212/debian-bug-leaves-private-sslssh-keys-guessable all Debian Private SSL/SSH keys ended up one of a few hundred thousand (or whatever), due to bad seeding. Probably an inside job, though :) 79.122.74.63 (talk) 15:25, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- That strikes me as being analogous to the VENONA situation, not someone actually cracking a not-broken PRNG on account of its being pseudorandom. The problem there wasn't the fact that it was pseudorandom, it was that it wasn't seeding correctly, ja? --Mr.98 (talk) 23:26, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think that's the question at issue. I think Wnt was assuming a one-time pad based on a PRNG, which as far as I know is not a commonly used encryption scheme, though in principle it should work given a sufficiently strong PRNG. The classical one-time pad is based on true randomness rather than a PRNG. --Trovatore (talk) 04:19, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Are there actually any cases of people being able to crack modern, strong encryption schemes because of insufficient pseudorandomness? (I'm not counting cases like VENONA where they accidentally duplicated the same random number sheets more than once which was a lucky typo, not a case of the algorithm being wrong. I'm also not counting toy cases where people demonstrate how pseudorandomness can be misleading — I mean actual cases of intelligently designed systems with intelligently used pseudorandom or quasirandom number generators.) --Mr.98 (talk) 03:24, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- The security of a OTP shouldn't be exaggerated - you have to get those numbers from somewhere. For example, you might use a random number generator which is easily reverse engineered. Or you can use a service like HotBits,[1] which I assume has its entire output archived to some handy-dandy NSA decoding disk somewhere in transit. More to the point, that sticker on your computer that says "Intel inside" isn't really talking about the brand of chip they used... Wnt (talk) 17:27, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The hard part of cryptography is key management. Encrypting something with an OTP is like locking it in an uncrackable safe. But now what are you going to do with the key to the safe? Lock it in another safe? What are you going to do with the key to that safe? Keep in mind that the key is as large as the thing it's protecting. So the safe gains you very little—you're trading the security of one item for the security of another item of the same size. You can leave the key unlabeled and hope nobody figures out which safe it goes with—that's one kind of security through obscurity.

- People talk above about using a pseudorandom number generator to make an OTP. That's impossible because it's part of the definition of an OTP that it uses truly random bits. Using pseudorandom bits in the manner of an OTP has a different name: a stream cipher. -- BenRG (talk) 19:48, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Strictly speaking that might be true, but I think the meaning is clear to anyone who understands what a one-time pad is in the first place. --Trovatore (talk) 23:42, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- When you say "understands what a one-time pad is" you must mean "understands what it means to exclusive-or two bit streams together". Some explanations of OTP seem to spend almost all of their time on that minor detail. Since the output of a stream cipher is also exclusive-ored with the plaintext, someone with that "understanding" of OTP might have a head start on "understanding" stream ciphers too. What OTP is actually about, though, is having as many possible keys as possible plaintexts. -- BenRG (talk) 00:50, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Oh, responding to your first paragraph: The key is the same size, but it doesn't need to be generated at the same time. You can exchange the key in advance (by exchanging physical artifacts such as DVDs), and then when the time comes that you know what secret message you want to send, you're good to go, and you can transmit the message faster at that time than you could get a DVD to the recipient. Obviously this isn't convenient enough for, say, online banking, but for certain applications it could be workable. --Trovatore (talk) 23:48, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- That's true, and OTPs have been used in that way by major governments (and they've screwed it up and their messages have been cracked). I think this is one of those if-you-have-to-ask things. Only in very specific circumstances is using an OTP a good idea, and people in those circumstances are not going to ask the likes of me for advice on the subject. So if someone does ask me, I can safely tell them they shouldn't do it. -- BenRG (talk) 00:50, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- There's an easy solution to this. Use the OTP as the lowest layer (pretend it's like the physical wire the bits go through), but make sure it's higher than any actual physical leak of information!! Then, at a higher layer, pretend all you have is the public Internet, and proceed to use the most secure protocol you have available. In this way, if you foul up your OTP exchange, you are left with the most secure protocol you have available. However, if you don't foul it up, you have the most security imaginable. The downside, as always, is the need to have the parties know ahead of time their need to communicate, combined with needing to take with them as much OTP as they will transfer in bits over the wire, ever. Finally, you should destroy the OTP somehow after using it, as perhaps it could be recovered. On the whole, why not have an OTP layer that you can prove secure, but is error-prone due to other than theoretical reasons, with higher layers being layers you can't prove secure? 188.157.9.122 (talk) 13:15, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- There's obviously no limit to how many times you can encrypt something, or what methods you can use. But there is the issue that, in a large organization such as a company or army, people might not always do the "right thing" when any one of those layers gets a bug in it and their comm channel turns into useless gibberish. There's a certain chance that one of them is just going to retransmit what they had through a clear channel or using an easily broken code hoping no one notices - and then, you've revealed not only that document, but possibly something about your fancy cipher system that just failed. Wnt (talk) 18:26, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- There's an easy solution to this. Use the OTP as the lowest layer (pretend it's like the physical wire the bits go through), but make sure it's higher than any actual physical leak of information!! Then, at a higher layer, pretend all you have is the public Internet, and proceed to use the most secure protocol you have available. In this way, if you foul up your OTP exchange, you are left with the most secure protocol you have available. However, if you don't foul it up, you have the most security imaginable. The downside, as always, is the need to have the parties know ahead of time their need to communicate, combined with needing to take with them as much OTP as they will transfer in bits over the wire, ever. Finally, you should destroy the OTP somehow after using it, as perhaps it could be recovered. On the whole, why not have an OTP layer that you can prove secure, but is error-prone due to other than theoretical reasons, with higher layers being layers you can't prove secure? 188.157.9.122 (talk) 13:15, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- That's true, and OTPs have been used in that way by major governments (and they've screwed it up and their messages have been cracked). I think this is one of those if-you-have-to-ask things. Only in very specific circumstances is using an OTP a good idea, and people in those circumstances are not going to ask the likes of me for advice on the subject. So if someone does ask me, I can safely tell them they shouldn't do it. -- BenRG (talk) 00:50, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Strictly speaking that might be true, but I think the meaning is clear to anyone who understands what a one-time pad is in the first place. --Trovatore (talk) 23:42, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

about mechnical force

what is easy to pull a stationary thing or to push it? what takes less force to pull or to push a thing whereas the idle conditions are considered such as friction is same for both pulling and pushing? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 27.124.12.98 (talk) 13:37, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- With the standard assumptions of an idealized physics problem, pulling or pushing an object requires the same force. In the real-word however, consider an example such as an adult human moving a 1 m cube of wood. Pushing often introduces a downward component of force. This can increase friction, making the object harder to move. Likewise, pulling might be done using a rope, which could introduce an upward force, reducing the friction, and making the object easier to move. SemanticMantis (talk) 14:07, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- There's more, isn't there? For pushing, isn't the best location for a vantage point somewhere such that you can lean your own weight against the wood, say at such a distance away that your body forms a 45 degree angle with it? Whereas, for pulling, you can only lean away from the wood as far as your arms go (or put another way, the same 45 degree angle would put your feet INSIDE the block of wood, with you leaning outwards and pulling). If you have a piece of rope, you can lean as far away as you like... I would say for this reason in an ideal world it's far easier to push than to pull anything, except when there is a rope or the like attached of sufficient length for you to lean however you like, in which case it's roughly the same... 188.156.144.183 (talk) 15:47, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- And note that pushing is unstable, and the object will want to "fish tail", as in a rear-wheel drive car, while pulling is inherently stable. Pushing some objects without wheels or skis also doesn't work well, since they will want to dig into the ground at the front. StuRat (talk) 19:02, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- that's interesting (and same as the friction answer given earlier, isn't digging in just increasing friction :)). Do you think the push/pull distinction above is valid StuRat? 79.122.90.56 (talk) 21:01, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- "Digging in" can go beyond just increasing friction. The usual def of friction is that the only work it does is to create heat. But if the object plows into the ground, it may also do work moving dirt. Or, consider a case where you push or pull a brick along a sidewalk. At the seam between two slabs, the brick may dig in, and then any pushing force is trying to move the entire slab of sidewalk. Note that this all assumes that you push above the center of gravity. Pulling above the center of gravity will also tend to make the front edge dig in, but, since you likely need to attach a rope or chain to pull an object, you can just as easily attach it below the center of gravity. StuRat (talk) 21:09, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- In the case of pulling, much depends on the presence of a handle or other device to pull onto. Consider also the case of pulling vs. pushing up an inclined ramp. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:40, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

about transformer

how can a transformer be worked in dc supply? — Preceding unsigned comment added by Lalit7joshi (talk • contribs) 13:42, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- [See Inverter (electrical)#Basic designs One way is by switching the DC back and forth so that it follows two different directions through the transformer primary. A distorted AC output is produced from the secondary of the transformer. The output can be at a different voltage from the input, depending on the turns ratio and frequency of the switching. In automobiles years ago, an electromechanical vibrator circuit did the switching, to produce high voltages via a transformer and then a rectifier to operate vacuum tube radios. In modern circuits used to step up DC to high DC voltages or to convert DC to AC, transistor switches or other solid state devices such as thyristors are used in place of the vibrator. Edison (talk) 14:53, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

Did Homo sapiens get their pale skin and red hair from Neanderthals?

Someone told me that sapiens got pale skin and red hair from interbreeding with neanderthals which already possessed these traits. I seem to recall in my Human Evolution class that neanderthals did indeed have these traits, but they were coded for by different genes so it was just an example of parallel evolution. Who is correct? ScienceApe (talk) 14:54, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Neanderthal_admixture_theory#Genetics seems to answer your question. SmartSE (talk) 15:50, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- For context consider that just about any mammal has red-haired members with some mutation or other in MC1R. Making redheads, genetically, is no big deal. Wnt (talk) 17:21, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

does near-UV light cause photobleaching of protein?

If they fluoresce under UV, shouldn't they photobleach too? How does the body repair this? 137.54.28.45 (talk) 17:36, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Damaged proteins can simply be replaced. Damaged DNA is more serious, but most of us do have a mechanism to repair that. Individuals with xeroderma pigmentosum lack this ability, so must avoid sunlight, as the children in The Others (2001 film). StuRat (talk) 18:37, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Autofluorescence isn't very much for most things, and neither is photobleaching; in fact, as mentioned in that article, advanced glycation end-products produce much of the fluorescence - in other words, damage done by other means already. So it's part of the normal wear and tear, but not that much considering, and of course evolution will have tended to lead to the marking of any particularly susceptible proteins for rapid degradation and replacement. See ubiquitination, proteasome, autophagy, endosome, lysosome ... no doubt I'm forgetting lots of biggies. To survive and thrive, cells have to be almost as good at recycling and replacing proteins as they are at making them to start with. Wnt (talk) 19:14, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

computer screens

Sorry, but for a rather bad pun/joke on another site, can anyone tell me what the letters shown on the computer screens are actually made of, what is within the part of the screen they take up that makes them different to the surroundings or whatever is going on in there?

148.197.81.179 (talk) 17:40, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- See Computer monitor. Feel free to ask here if anything is unclear. --Daniel 17:43, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- It depends on the type of monitor being used. On an old style CRT, it's just particles (electrons) being beamed on to a screen that begins to glow due to fluorescence I believe. ScienceApe (talk) 17:52, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The letters, as well as everything else on the screen, are made up of pixels. Those are actually each a dot or square, but when tiny dots are placed close together, you see them as letters or pictures, as in a dot matrix printer or in Pointillism paintings. If you look closely you may see the dots. A magnifying glass or a drop of water on the screen may help. TVs use similar technology, but often have bigger pixels, which are easier to see up close. StuRat (talk) 18:18, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- You may be interested in these magnified images of text, shown on ipad and kindle screens [2]. Of interest is the fact that neither one uses uniform placement of square pixels. SemanticMantis (talk) 18:35, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The pixels on the iPad and Kindle in that article are arranged in a square grid. They aren't perfect squares, but that's as close to perfect squares as you'll ever see. Most CRTs used a triangular/hexagonal grid (File:CRT pixel array.jpg). -- BenRG (talk) 19:30, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

Can Potassium nitrate (KNO3) be used to supply oxigen for breathing in close quarters?

By use I mean - by common utensils. Is it enough to heat it to release Oxygen? 109.64.24.206 (talk) 18:21, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Note that with overheating the remaining potassium nitrite decomposes to produce nitrogen oxide, i.e. concentrated smog. The same might be true if it is impure, mixed with other cations. I wouldn't count on the oxygen to be "suitable for breathing" except in some specific, well designed application. Wnt (talk) 19:21, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The propensity that potassium nitrate has for decomposing explosively would be a very real problem. If it happens in close proximity to the user the need for breathable oxygen may be ended. Short version: The stuff explodes rather easily! Roger (talk) 19:31, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- See oxygen candle - KNO3 may not do the job, but there are other things that will. --Tango (talk) 22:54, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

Wnt, Dodger67 and Tango - thank you VERY much for your answers. You have helped immensely. 109.64.24.206 (talk) 15:51, 5 February 2012 (UTC) (OP)

Using the turntable in a microwave oven

The article Microwave oven contains this sentence: In turntable-equipped ovens, more even heating will take place by placing food off-centre on the turntable tray instead of exactly in the centre.

Can anyone either give me a reference for why this is so, or offer an explanation comprehensible to a someone who is not even an amateur scientist? Thanks, Bielle (talk) 20:51, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- The heating of a stationary object will be uneven, with some spots getting more heating and others getting less. By rotating it, you average out all the spots at that radius, which is bound to give a heating amount closer to the overall average. The farther from the center, the more spots are averaged out, while at the very center, there's only one spot, so, whatever heating level the center would get if stationary, it will still get when rotating. If your microwave oven happens to heat the average amount in the center, you will be OK, but, if not, rotating won't improve things at the center. StuRat (talk) 21:03, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks, StuRat! Bielle (talk) 22:08, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- You're welcome. I will mark this resolved. StuRat (talk) 22:10, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

From the article "Children and adolescents are particularly sensitive to the early and late extrapyramidal side effects of haloperidol. It is not recommended to treat pediatric patients." I would like to know where I can read more about this. If there isn't a citation available, perhaps someone can direct me to a specific person i could contact? Thanks198.189.194.129 (talk) 21:47, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Not sure, but note that our article contradicts itself by listing children under the "Uses" section. StuRat (talk) 23:20, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

This paper is a recent review of the relevant literature, at least as regards schizophrenia, and is freely available online. Looie496 (talk) 03:17, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- To begin with, a good way to get information here is by PubMed [3] or Google Scholar [4] which deliver 700 and 24000 references respectively (though Google often absurdly overestimates and you don't find out until the last page). PubMed is much nicer to work with because it's sorted by date and indicates which resources are available for free.

Adding "adverse" to my search I found [5] which says that in treatment of tic disorders, "all 17 subjects in the haloperidol group experienced unexpected side effects and 6 (35.3%) were not able to continue medication owing to unbearable adverse events." But it was an open-label study, and the other drug has less of a reputation, so I'm not sure it's really any better. Also it says the extrapyrimidal symptoms and the rate of discontinuation were worse in this group than in an alternative group receiving aripiprazole.

This is clearly a tricky decision between bad options and I'm not going to claim my casual browsing is nearly enough to get to the bottom of it. Wnt (talk) 18:41, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks, all of you.-Richard Peterson198.189.194.129 (talk) 16:48, 9 February 2012 (UTC)

Is it safer at 5 pm after dark or 8:30 pm in the daytime?

At least theoretically? Not that I live in a dangerous area (crime rates are close to the national average (US)), just curious. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 22:52, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- It's going to depend on a lot of things. Light certainly helps prevent crime, but so do potential witnesses. If there are a lot of people around at 5pm and not many people around at 8:30pm, crime could be higher at 8:30pm despite it being lighter. --Tango (talk) 22:56, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- That might be true of an area where people work (approximately 9-5) but don't live, for example. The assumption being that the question is asking solely about safety from crime. As for safety from traffic accidents, full light is better, but sunset and dusk can be even worse than total darkness, since people's vision may be obscured by the Sun and some may not have their lights on yet. StuRat (talk) 23:15, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- It's difficult to figure this out, because even knowing the crime rate isn't enough. For example, this analysis finds crime in San Francisco to be highest from 4 to 8 p.m. But what that omits is that to a particular person walking late at night, the lower overall number of crimes is little comfort when he has so few people to share them with. I think that despite the increase in crime rate per time of day, the best guide is still the instinctive feeling that when you're one of just a few passersby, the whole criminal element has the chance to put you in their sights. Wnt (talk) 23:24, 3 February 2012 (UTC)

- Certain studies have found that street lighting only reduces the fear of crime without having any noticeable impact on actual crime rates[6]. Sunshine can cause other problems, like traffic-disrupting glare in the early mornings and late evenings. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:34, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- (didn't have access to internet for awhile) Also not mentioned is how late things close in your town or neighborhood. First the stores, then the movie theaters and finally bars. I'd imagine there might be some places so hickey that everything can close before sunset. Imagine walking in the ghetto of Anchorage or Fairbanks (if they have ghettos in Alaska) at 11:42/12:47(a) and it's still daylight. Or getting only a few hours of weak sun all winter and having to be in your cubical for all of them. It'd be a surreal feeling. (though Russia would probably be a more likely place to find ghettos) Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 23:58, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

February 4

Pterodactyl

Would a pterodactyl be strong enough for a person to be able to ride on its back? --108.225.115.211 (talk) 00:31, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Wouldn't you be hit by flapping wings there ? StuRat (talk) 00:33, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Very doubtful. What would be the point of having that extra strength? The extra muscle mass would mean they need to eat more, which would decrease their chance of survival. Evolutionary pressure is very strongly towards flying creatures being as light as possible and no stronger than they need to be to get off the ground (and perhaps to pick up prey, but according to pterodactylus only had a wingspan of 1.5m, so they weren't large enough to eat human-sized prey). --Tango (talk) 00:41, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

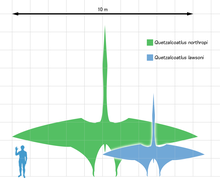

- Pterosaurs in general grow to be much larger, up to a 10m wingspan (see Pterosaur size). They seem to have a lot of tricks that help keep them aloft at that size, including internal air sacs to reduce their density as much as possible. The article of one of the largest pterosaurs, Quetzalcoatlus, talks about their weight (70-200 kg), them needing to vault themselves to get airborne, and includes an illustration of them doing their feeding on the ground. Most of the mighty predatory birds that need to do some impressive lifting feats (like the mighty eagles dropping goats off of cliffs) start lifting mid-flight, having a lot of momentum built up to work with, but is not sustainable flight - they lose altitude continuously.

- To answer your question, at the high-end estimated weight of a Quetzalcoatlus, it may have more room to spare in terms of carrying capacity than one would think, but a 200kg flyer could certainly never haul a 100kg person with any lift. I can't give a calculated estimate without years of incredible engineering research as these scientists have employed, but I can tell you immediately that each downbeat of the wings has to be at least 25% more powerful than normal and 50% more frequent. That's like me jogging to the grocery at a comfortable 8-minute mile, but then having to carry food back at an impossible 4:30. SamuelRiv (talk) 01:22, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- (e/c) No. The largest pterodactyls (suborder Pterodactyloidea) are the members of the family Azhdarchidae, the azhdarchids. Azhdarchid flight is relatively poorly known, but like SamuelRiv said, they are believed to engage only in limited anaerobic (flapping) flight, and be predominantly soaring/flap-gliding animals that utilized columns of rising air to keep aloft. They launched by a running/flapping start and the addition of half to a third (a human's weight) of their current estimated body weight (~200 kg (440 lb) for an azhdarchid with a wingspan of 10 to 11 m (33 to 36 ft)) would make that quite impossible. Not to mention the aerodynamic drag and balance problems produced by a human rider. Azhdarchids are also believed to be stalkers, hunting their prey on foot like modern storks, not skimmers like some of the more commonly known marine pterosaurs (e.g. Pteranodon). They can not pick up prey while in flight because of the drag produced. A human riding them would produce similar if not even more catastrophic drag.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 01:43, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- But according the article, many of those claims of large-animal flight, consistent with today's birds, are under dispute for pterosaurs. Surprisingly to me, there are apparently models for flight that is athletic and dynamic like a swallow, not soaring like an owl. As an analogy this might be improper, but one might consider in human flight, the size and shape of a plane varies greatly with what it has to carry - in no sense can one make a plane "scale up". So to make a small one-person recreational airplane carry 20 people, you can't simply make the wingspan 20 times bigger and/or the engine 20 times stronger - you have to redesign it. SamuelRiv (talk) 18:45, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Swallows are dynamic soarers actually. They do not engage in much anaerobic flapping. While azhdarchids are more likely to be such, given their shape and the velocities they can achieve, and not like the heavy poor flyers of today (like pelicans); also consider the fact that the faster they fly, the greater the effect of parasite drag. An extraneous human clinging on its back would produce such a drag. The paper points out the inappropriateness of the comparison with birds. The shape, lack of feathers, bend location, muscle structure, wing membrane (with matted pycnofibers that give it additional structural integrity) and bone strength of azhdarchids are too different from birds for any accurate comparisons. Thus the older estimates of azhdarchids only having an estimated weight of 80 kg (180 lb) for an individual with a 36 m (118 ft) wingspan used for the flying model is now considered wrong. But that argument is really only useful in refuting the assertions that azhdarchids were flightless. 70 to 100 kg (150 to 220 lb) human is still a third to half of the largest pterosaur's weight. Unless they had propellers, they wouldn't even be able to launch, much less keep aloft.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 01:34, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

Cycloaddition Mechanism

Hello. What is the reaction mechanism for the addition of dichlorocarbene to cyclohexene? Cited sources are appreciated. Thanks in advance. --Mayfare (talk) 06:35, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- We have an article about dichlorocarbene, with a section entitled "Reactions" that tells you the product but not the mechanism. But it also suggests that the "dichloro" and the "cyclohex" details might not be important (they are not altered by the change taking place in the given reaction). So take a look at the more generic carbene article and maybe in particular the "Reactivity" section. DMacks (talk) 15:18, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

Most numerous vertebrate species

I recently heard a naturalist claim that humans are the most numerous vertebrate species. Is this true? If so, which other vertebrate species have populations in the billions? I would have thought that the brown rat and some domesticated animals would challenge humans for numbers. Warofdreams talk 13:47, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- That definitely sounds wrong. Biomass (ecology)#Global biomass says there are more chickens. Chicken says it is the most common bird. I guess there are other more common vertebrates. PrimeHunter (talk) 14:23, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think anyone really knows. He's wrong, but probably not by much, we'd probably be in the top 50 or something, few species are really readily adaptable to a wide range of ecological conditions like humans are. And to be fair, the most likely candidates (domestic and synanthropic animals) only attained their population sizes and distribution because of humans. On the opposite end of the spectrum, passenger pigeons which was believed to have once reached an estimated population of 3 to 5 billion were singlehandedly decimated to extinction within a century by humans.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 14:34, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- The brown rat article claims there are 1.3 rats in the UK per person (which, if it's true, would obviously push the rats ahead of the humans). But it cites an hysterical piece in, of all sources, The Sun, which takes its info from Rentokil (Britain's largest ratcatcher, in whose interests it surely is to embiggen the "rat threat"). Snopes cites rather better sources for New York City claiming a ratio of only 1:36. -- Finlay McWalterჷTalk 15:00, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Rodents aren't limited to cities, they also do quite well in farm fields. In the U.S., we have around 220 million acres just under corn, soybeans, and wheat, and, even at a conservative estimate of 40 rodents/acre, U.S. grain field rodents are more populous than humans. (They also love fruit orchards and grass, e.g. alfalfa fields.) However, most of them are not brown rats, they are meadow voles.--Itinerant1 (talk) 19:56, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Rodentia, however, is not a single species. Few rodent species are truly cosmopolitan, and the ones that are are synanthropic species that stay close to human habitations. Field mice in Pakistan, for example, will be most likely to be a different species than field mice in Iowa. In contrast, a Norway rat in the Hong Kong sewers would be the same species as a Norway rat in New York.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 00:56, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Rabbits certainly number in the billions, though they aren't a single species either. I'm sure there are some vertebrate fish like herring that would give us a run for our money (according to the herring article there can be up to four billion in a single school)

. And there were 24,000,000,000 chickens as of 2003. 112.215.36.185 (talk) 05:15, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- fish are vertebrates, right? Surely there are several species of small fish hat have a larger population than 7 billion. --Lgriot (talk) 00:43, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- Gonostomatidae (a family of deep-water marine fish) says: "Cyclothone, with 12 species, is thought to be (along with Vinciguerria), the most abundant vertebrate genus in the world." See also http://www.nefsc.noaa.gov/faq/fishfaq1.html#q5. I guess it's hard to estimate how many billion small fish there are in deep water around the world. PrimeHunter (talk) 03:01, 7 February 2012 (UTC)

back muscles

When I lean backwards whilst standing, my abs and (to a lesser extent) chest muscles flex to help me maintain position. When I lean forwards my back muscles do the same. So why, after carrying a heavy backpack all day, do my back muscles hurt and not my abdominal/chest muscles? This seems counter-intuitive. The Masked Booby (talk) 14:43, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- DIdn't you just answer your own question? With a backpack on, you lean forward. 79.122.74.63 (talk) 15:21, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Both muscle groups would have to act with each other to stabilize your backpack, so both would be working. A backpack is fairly efficient, though, so the group to feel the most soreness would be the group that is least used to this type of heavy work. For me at least, my that mid-lower-back area doesn't see a lot of heavy or long-term exertion, even in any sport I play. SamuelRiv (talk) 18:52, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

Is it possible to improve vision with eye exercises

my friend told me that it is possible. if it is then please tell me some eye exercises RahulText me 15:08, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Bates method. (Googling "eye exercises" leads you to loads of pages, including a wikihow site.)--TammyMoet (talk) 15:31, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I personally used to use the Bates method, because my initial experience with it was surprisingly good. I tried palming, and afterwards my vision was noticeably clearer for a little while (less than a minute). I started believing the claims, but no matter what, it doesn't do much in the long term. Once I did manage to shave about a diopter off my prescription, but there is no way of knowing if that was just because my eyesight was unnaturally bad due to stress, or whether it was some other effect of the treatment. Also, the eyesight eventually went back to what it was. When I finally read the research, I gave up pretty quickly, regardless of the initial experience. IBE (talk) 15:54, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- If the Bates method is of any value at all, is it that it reminds one that the eyes focus by the means of muscles and if they don't get enough exercise they weaken. I can understand IBE's comment because I can't say that his (Bates) exercises appeared to do me any good when I tried them. Yet, I noticed after I stopped working in an office (where every-day I was only focusing 10 – 15 ft at the most and most of the time a lot shorter and a similar amount in the evening glued in front of the TV) that my eyesight improved to the point where I forgot to wear my specs because I could see well enough without them. Maybe also, because I then needed to take notice of vertical line as well as horizontal that my bad astigmatism became negligible. Thus, I think that just doing a few exercises from time to time it not really enough to make a major improvement, as they don't exercise the muscles enough. Also, as one grows older, atrophy of muscles, due to lack of exercise, takes less time to occur. Extended Bed Rest Accelerates Muscle Deterioration In Older Adults. Some might consider this last comment trite, but older friends of mine that have only spent a few hours in the Pub, focusing no further than the bar-maid, come out, unable to see their way home – and back to the wife. I tell you -this is the truth. Old age is not very kind – so don't go there. --Aspro (talk) 19:59, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

Vitamin D may also be beneficial to eye health. Count Iblis (talk) 00:00, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Weakening of the ciliary muscle with age, which regulates the accomodation reflex, tends to result in presbyopia, or reduced ability to focus on near objects. There is definitely variation in ciliary muscle strength between individuals of the same age, so any valid eye exercises may focus (no pun intended) on these muscles. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:25, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

Why can animals be classified as vertebrates or invertebrates if vertebrates only make up one phylum?

I simply don't understand why scientists have to classify animals as vertebrates or invertebrates. Invertebrates make up several phyla, while vertebrates are in only one phylum? Yes I know humans are vertebrates, and that fact can lead to bias (like the Old World and New World stuff) but remember, not all chordates are vertebrates. Was it done for the sake of convenience, or just because chordates are somehow special? And what current phylum has the most similarities with chordates? Narutolovehinata5 tccsdnew 15:23, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Scientists classify things in whatever ways they think will be useful. Vertebrates have a lot of similarities to each other that they don't have with invertebrates, which makes it a useful classification. You won't find scientists talking about invertebrates much since, as you say, they are so varied - you would want to talk about a specific subset of invertebrates. The word only exists to distinguish them from vertebrates, rather than as a classification of its own. --Tango (talk) 15:54, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Of course, there is a discussion of this very topic in Wikipedia: Invertebrate#Significance_of_the_group. --Tango (talk) 15:58, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- (WP:EC)See Invertebrate#History and Invertebrate#Significance_of_the_group. The term was coined by Lamarck, who himself is responsible for making further taxonomic subdivisions (Linneaus apparently divided all invertebrates into insects and worms). The article goes on to say "the (invertebrate) grouping has been noted to be "hardly natural or even very sharp."" Suffice it to say, it is a useful term for casual conversation, and does reflect some bias, but is not really used with much scientific weight. Also, just to clarify: "invertebrate" is not a "classification", it has no place in taxonomy or phylogeny, and as you point out the group is highly paraphyletic. It has the same scientific level of rigor as a term like "Non-ant insect". In short, the term is still used because it is useful, and is fairly well-defined. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:09, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Right. Classifying animals as vertebrates and invertebrates is a bit like classifying people as Americans and foreigners. If you live in America the classification is useful, but it is not a very meaningful distinction from a global point of view. Looie496 (talk) 23:57, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- It's a very old classification system, back when people didn't truly appreciate the vast differences between groups of organisms and were still a bit anthropocentric in that they consider vertebrates to be more important than anything else (after all, they are usually the largest organisms). Today, Invertebrata is not a formal taxonomical rank (note its article does not have a taxobox in contrast to subphylum Vertebrata). It's merely a colloquial grouping meant to quickly distinguish vertebrates from non-vertebrates.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 00:51, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

On the similarity thing, echinoderms are the only deuterostomes other than the chordates and were said (at least when I was in high school 15 years ago) to be the phylum most closely related to chordates (and by "most closely related," I think I mean that on a cladistics graph, they branch most closely to or in concert with chordates in some fashion or another). DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 06:14, 7 February 2012 (UTC)

Basic iTunes question

Sorry, this is really basic, and please transfer it to Entertainment RD if that's more appropriate. I am gradually ripping all my CDs and putting them onto an iPod, using iTunes. It is taking up more space than I would like on my hard drive. If the music is safely on the iPod, how can I easily take them off the hard drive, or compress them, or whatever? ITunes seems to want me to have everything on both the hard drive and the iPod, "synchronised". Thanks. Itsmejudith (talk) 18:31, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- You would probably be better off on the Computing desk. --Tango (talk) 19:02, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- (ec)You might do better at the Computing desk than either! Not having used it, my hazy understanding of iTunes is that it is mostly for copy-locked (DRM) music files rather than for the all-purpose files from a ripped CD, and so a simple general purpose sound playback program might do better. But the extent of my musical forays nowadays is YouTube running Video DownloadHelper (with NoScript to block the VEVO ads ;) ) Wnt (talk) 19:04, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- This is not true at all. You can use iTunes to manage any MP3s or other media files. They don't have to be DRMed at all, and usually aren't if you are ripping them from your own CDs (which you can do within iTunes easily). They are only DRMed if you get them through the iTunes store, which you're under no obligations to do. I don't think anybody cares about how you pirate music and I'm not sure why you offered that up as an answer. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:59, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- I thought most/all? music downloaded from iTunes is DRM free by now? Nil Einne (talk) 07:42, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- This is not true at all. You can use iTunes to manage any MP3s or other media files. They don't have to be DRMed at all, and usually aren't if you are ripping them from your own CDs (which you can do within iTunes easily). They are only DRMed if you get them through the iTunes store, which you're under no obligations to do. I don't think anybody cares about how you pirate music and I'm not sure why you offered that up as an answer. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:59, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Pirate? Why, how can I possibly pirate music by downloading it from the authorized publisher publishing from his official YouTube account? Wnt (talk) 03:53, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- It depends greatly on your local laws. Nil Einne (talk) 07:43, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Pirate? Why, how can I possibly pirate music by downloading it from the authorized publisher publishing from his official YouTube account? Wnt (talk) 03:53, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- You can set iTunes to "Manually Sync" your iPod. That way, it won't attempt to automatically make the two libraries match every time you plug it in. You can then safely delete music from your computer's hard drive, without affecting the iPod as long as you don't try to sync the whole music library manually. Usually, I prefer to set it to Manual and only select specific playlists to sync to my iPod. As long as you keep that music on your computer's hard drive, it won't have any problems. — The Hand That Feeds You:Bite 19:15, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- You can also just set it to manually manage (not sync at all). Set up in this way, you move music to the iPod by dragging it within iTunes. You can then delete it off of the main computer if you want. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:59, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- Thanks folks. Itsmejudith (talk) 20:52, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- You can also just set it to manually manage (not sync at all). Set up in this way, you move music to the iPod by dragging it within iTunes. You can then delete it off of the main computer if you want. --Mr.98 (talk) 20:59, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

Parrots (e.g. Amazon)

Is it true that male Amazon Parrots usually get on better with women and that female Amazon Parrots get on better with men? Something to do with pheromones? Thanks.

Also (I asked this before but I don't think I got an answer, can't find the question now), is it just a coincidence that a baby Goffin's Cockatoo makes a noise that sounds a lot like a human baby? e.g. like http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zLAp98VVuao --95.148.105.157 (talk) 21:50, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

binary star info

Can someone give the formula including 3 numbers: solar mass of both stars, separation distance, period. So if i was given 2 out of the numbers i can figure out the other one. So a formula that including all of 3 info above. Thanks!Pendragon5 (talk) 22:50, 4 February 2012 (UTC)

- The separation distance isn't necessarily constant, for elliptical orbits. StuRat (talk) 00:07, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- The deviation of an elliptical orbit from perfectly circular is known as its orbital eccentricity, where a value of 0 is a circle and 1 is a parabola. The average distance between two objects is the semi-major axis, and the centre of gravity between a system of gravitationally-bound objects is its barycenter. You may try finding some 2-body simulators online, as the mass of either object does affect the shape of the orbit, or compare some real-life examples such as Capella versus Epsilon Aurigae. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:15, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I need a formula.Pendragon5 (talk) 02:14, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- The deviation of an elliptical orbit from perfectly circular is known as its orbital eccentricity, where a value of 0 is a circle and 1 is a parabola. The average distance between two objects is the semi-major axis, and the centre of gravity between a system of gravitationally-bound objects is its barycenter. You may try finding some 2-body simulators online, as the mass of either object does affect the shape of the orbit, or compare some real-life examples such as Capella versus Epsilon Aurigae. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:15, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

And let assume that the separation distance is constant.Pendragon5 (talk) 02:34, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- According to Standard_gravitational_parameter#Two_bodies_orbiting_each_other, the relationship is 4π2r3/T2 = G(m1 + m2). 98.248.42.252 (talk) 03:06, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I was going to derive it from scratch, but then saw Kepler orbit. Basically looks like the standard Kepler equation, and just set all eccentricity terms (e, E) to zero. SamuelRiv (talk) 03:32, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think this equation, 4π2r3/T2 = G(m1 + m2), is what i'm looking for. I'm looking for the equation include the solar mass of the stars, the period of the star (how much time it took for them to orbit each other once), the separation distance.Pendragon5 (talk) 19:51, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- See below. That's the exact equation you are looking for, as m1 and m1 are the masses, G is the "big G" gravitational constant, r is their seperation distance (as measured from their centers), and T is their orbital period. I've explained in more detail below, with links, before I knew you also asked it up here. --Jayron32 20:49, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think this equation, 4π2r3/T2 = G(m1 + m2), is what i'm looking for. I'm looking for the equation include the solar mass of the stars, the period of the star (how much time it took for them to orbit each other once), the separation distance.Pendragon5 (talk) 19:51, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- I was going to derive it from scratch, but then saw Kepler orbit. Basically looks like the standard Kepler equation, and just set all eccentricity terms (e, E) to zero. SamuelRiv (talk) 03:32, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

February 5

Water decapitiation or being squashed like a pancake?

Suppose the US has the capabilities to construct a 5,000-ton (but only about 1000 tons' worth of space available to the crew) submarine that has a super-strong titanium hull capable of withstanding great pressure. Suppose that the sub is at the bottom of Mariana Trench, and water is leaking through a 5 mm hole in the ceiling. There is only enough food and water supplies to last the single submariner another 24 hours. He has two options -- to wait until the sub fills up and die due to drowning in the cold water and the immense pressure, or instead position his head underneath the leak so the rapid leak could kill him. Now he doesn't know how quick the leak is and how fast the water is travelling, so he hesitates. Can somebody help him out by calculating the water's actual velocity, and the water's required velocity at which the submariner's head will get punctured instantly and die? --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 00:05, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Note that the rapidly moving water will also rapidly enlarge the hole, so they wouldn't need to get bored waiting to die. :-) StuRat (talk) 00:10, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Suppose all the dimensions stay the same. --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 00:16, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- This sounds like a homework problem, no? Well, it would be a good one, and I don't use numbers. We could of course calculate the water pressure at that depth, but the Mariana Trench article provides it: 109x106 pascals (N/m^2). Pressure is force per area, and the area into which the force is being applied is a 5mm hole and A=πr2, which gives the force of the water flowing in. To break a neck, I'll just use the Hanging#Long_drop article for the heck of it: 5600 N. I get 2000 N from the water stream (full calculation left as exercise for the reader). Note that the smaller the hole, the less force, so you might want to widen it to a couple cm before you go a-suicidin'. SamuelRiv (talk) 03:02, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- What would the water velocity for both cases be? --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 03:13, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

The velocity will be affected by three things: 1. The orrifice effect as the water transitions from the sea into the hole, 2. The viscous drag while in the hole, and 3. the orrifice effect as the water transitions from the hole to the air inside the hull. You can get 1 & 3 from tables in hydraulics and/or fluid dynamics texts, and (2) can be calculated by applying the Fanning-Darcy equation arranged to solve for flow given the pressure drop, length of the hole (= hull thickness), and the viscosity of water at the temperature that exists at that depth. Fanning Darcy has 2 forms - one for laminar flow, one for turbulent flow. You need to first calculate the Reynolds Number, dependent of hoile dimensions and viscosity, to decide which Fanning Darcy to use.

So, you need to know the thickness of the hull. Unless you think titanium is so strong the hull is paper-thin - not realistic. Keit124.182.20.59 (talk) 03:43, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- If the hull is 2 cm thick, what's the velocity? --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 03:45, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

Look up "Reynolds Number", look up "Fanning-Darcy equation", and look up a good text for tables on the two orrifice efects, and do the math. I'm happy to point you in the right direction, but not to do your homework. Keit124.182.20.59 (talk) 03:49, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Naive velocity estimate is 400 m/s. SamuelRiv (talk) 04:01, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

This is not h/w. I was just curious. And wow, 400 m/s! --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 05:19, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

This is not h/w. I was just curious. And wow, 400 m/s! --Sp33dyphil ©hatontributions 05:19, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- And (assuming my maths is right, which it may very well not be), it will only take 159 seconds or thereabouts to fill your 1000 M3 space with water anyway, with it coming in through a 5mm diameter hole at 400 m/s. I don't think that food and water supplies are going to matter much here. AndyTheGrump (talk) 05:55, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

I suspect the 400 m/s flow is just a guess. But assuming it's right, 400 m/s thru a 5 mm hole is 0.00785 m3/sec. That will need 35.4 hours to fill the 1000 m3 sub. Keit58.170.173.63 (talk) 07:08, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Er, yes. I've probably got this wrong, on consideration. Though I'm not convinced you're right either. Maths was never my strong point... AndyTheGrump (talk) 07:20, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- ~35 hours is correct, given the assumptions. Your value, Andy, would require the hole to have 800 times the area it does. As for the flow rate itself, if we are allowed to ignore friction, I believe 464 m/s is a more accurate value. Although perhaps Sam's naivete operates on a higher level than my own, and he is able to do guess the affect of friction. Someguy1221 (talk) 07:38, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Er, yes. Third time lucky, and I get the same answer: 35.37 hours, give or take. Never ask a bloke with a social science degree to design a submarine ;-) AndyTheGrump (talk) 08:28, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- 400m/s was not a guess, but calculated using the hole bore volume to get the effective mass being ejected, without consideration for hydrodynamic effects. The water that actually exits will be very much more of a spray than a jet because of its turbulent speed and diffraction off the hole edges, and the work of displacing air will slow down the flow soon, but this is a nice upper limit. SamuelRiv (talk) 22:37, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- "mass being ejected without consideration of hydrodynamics"??? I would have thought that hydrodynamics, ie.e, Fanning-Darcy equation, is at the core of the calculation - please explain. Displacement of air can be neglected: Starting air pressure inside = atmospheric sea level pressure = 1 Bar, and the water pressure at the bottom of the Mariana Trench = 1000 Bar. Therefore, it's not until the air in the hull is compressed to less than 0.1 % of its volume that its presure will be comparable to the sea. Don't forget to allow for the Ratio of Heats for air (1.404). Keit60.231.241.252 (talk) 01:18, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think displacement of the air can be neglected, since 400 m/s is faster than the speed of sound in air. In other words, it's a supersonic jet ;) Gandalf61 (talk) 08:41, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

- Good point, I didn't think of that. However, upon thinking about it, the ratio of sea pressure to starting air pressure is so great (1000:1) it still won't matter. What might matter is that the resulting shock wave in such a confined space might knock out all the humans forthwith. Though I don't accept (without evidence) that the 400 m/s value has been correctly estimated anyway. Keit121.221.76.67 (talk) 12:42, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

What kind of spectrum is this?

Hi. One day while glancing over the surface of the water in a partly-full water bottle in a room with windows at the back and fluorescent lights over top, I noticed an unusual spectrum. At least part of the spectrum was likely from the fluorescent lights, but probably not the part you'd expect, since I observed the fluorescent spectrum in water to be very similar to the natural white light spectrum. I will list the colours of this spectrum in order, but keep in mind that italic text signifies what I call "narrowband", bold what I wrote down as the thickest part of the spectrum, taking up almost half of the entire spectrum, and underline for colours seen very narrowly at the edge of some transition, possibly into fluorescent lighting or ambient ceiling.

- Tan

- Pink

- Rouge

- Magenta

- Violet

- Indigo

- Navy

- Blue

- Green

- Teal

- Lime

- Tan

- Haze

- Orange

- White

- Orange

- Red

- Mahogany

- Violet

- Magenta

- Venusian

- Clear

Now, any idea what this spectrum may consist of? There did not be any objects directly contributing, unless there was a ubiquitous green backpack or other container within my line of sight. Thanks. ~AH1 (discuss!) 01:04, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- How in the world did you come up with those color names? Looie496 (talk) 02:52, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- You should ask Roy G. Biv. Edison (talk) 03:27, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- It's hard to picture an image from such descriptions, but the first non-bold colors seem to match those of the supernumerary rainbow depicted in the article. Reportedly this has something to do with interference... but I can't really speculate exactly how that appeared in a water bottle. Wnt (talk) 03:58, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- You should ask Roy G. Biv. Edison (talk) 03:27, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

The normal spectrum sequence is seen with oil films on water surfaces due to interference within the oil. Your observed effect could be due to viewing this through another oil film on the inside surface of the bottle. This could thru addition provide more colours. Keit124.182.20.59 (talk) 03:59, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

In other words, AstroHurricane is not looking at a "spectrum," but rather a "colorful array of refracted and diffracted light." The root cause for such a colorful display is the same as prismatic diffraction - optical dispersion - but whatever was causing the diffraction was not high-grade, precisely-ground polished optical glass. Consequently, you see a muddied mix of a lot of different light, including some regions where clean spectral lines might have been visible. AstroHurricane, perhaps you can build your own spectrometer, using these ordinary house-hold materials, and let us know if your spectrum looks any cleaner. If you have access to a laboratory-grade prism, you can build an even better spectrometer, and should get even cleaner results. Nimur (talk) 16:37, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

Earth spin and distance to the sun

Sir, suppose if the spinning speed of earth (around its own axis)is doubled what will happen to distance between the sun and earth. will it increse or decrease? — Preceding unsigned comment added by Tobyaickara (talk • contribs) 12:55, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Why do you think it would change? I can see no reason why it should. AndyTheGrump (talk) 15:21, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Perhaps you should read tidal locking and orbital resonance. The orbit does affect the axial rotation in a very complicated way; the two parameters are, effectively, "coupled oscillators." Objects with larger orbital axis are much more weakly tidally-locked, effectively meaning that the time-constant for the resonant locking imcreases very significantly. We could go through calculations that are outlined in the articles I linked, if you have questions; but the OP will need to specify some details if they want a mathematical answer. As I always mention when people ask questions about cosmological hypotheticals: in order for us to answer correctly, you will need to be more specific: how would the Earth's orbit or axial rotation change speed? For example, would it be due to an impact with another object? In the absence of a cause, conservation of momentum - specifically angular momentum - tells us that there should be no change without outside interference.

- Anyway, here is the equation that defines the most important part of the original question: the relation defining the time constant of axial rotation resonantly locking to the period of orbital revolution. Note the dependence on the semimajor axis of the orbit. If you want a more rigorous, less approximate form, I recommend de Pater and Lissauer's Planetary Science text, which covers orbital parameters very extensively and mathematically. Nimur (talk) 16:27, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Another effect might be that the Earth would lose some of it's atmosphere, which would reduce the Earth's mass. However, I wouldn't expect this to be significant (but either would the tidal locking, due to the Sun's distance from Earth). StuRat (talk) 23:12, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- These effects are small (especially since there is no rotation–orbit resonance for the Earth), so, initially, and to a good first approximation thereafter, AndyTheGrump's intuitive reply of "no effect" on the year or distance if the day length was to be magically halved seems reasonable. In reality, as Nimur explains, magic doesn't happen. Dbfirs 22:47, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

Is amphibia a paraphyletic group?

Kinda related to the invertebrate question, seems like invertebrates are a paraphyletic group since it does not include all of the descendents of invertebrates (like vertebrates), so is this the same for amphibia? I know we evolved from tetrapods, which we are part of, but did we at one point evolve from a lifeform that was for all intents and purposes, an amphibian? ScienceApe (talk) 17:44, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- See Pederpes, which we describe as "Amphibia sensu lato". In Linnean taxonomy it is an amphibian, but in cladistic taxonomy it is a tetrapod. Other fauna from Romer's Gap may also be interesting to you. Wnt (talk) 17:53, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- "Invertebrata" is polyphyletic, not paraphyletic.See note And define "amphibian". Do you mean living amphibians (Lissamphibia) or Amphibia sensu lato (all non-amniote tetrapods - Temnospondyli, Lepospondyli, and Lissamphibia, etc.)?

- Amphibia sensu lato (i.e. including all extinct forms) is paraphyletic, since it does not include Amniota (reptiles, birds, mammals, including extinct forms).

- If you meant the Lissamphibia alone. Quick answer is we don't know. See Labyrinthodontia#Origin of modern amphibians. Theories range from a monophyletic Lissamphibia derived from Lepospondyli; to separate origins of Caudata from Temnospondyli; to separate origins of caecilians from other amphibians sensu lato closer to amniote ancestors or even porolepiform fish (!).

- Also see Tetrapod#Phylogeny. Note location of Amniota and Lissamphibia.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 18:48, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- Note: the traditional classification of Invertebrata included [macroscopic] animals from more than a dozen different phyla while excluding common ancestors ("Insecta" and "Vermes"). It even included plants! This is not even taking into consideration the problem of whether Metazoa (Animalia) itself is monophyletic or polyphyletic. But yeah I guess, Invertebrata can also be said to be paraphyletic in relation to vertebrates, but that's a bit superfluous. Like assembling a doll with three arms, two heads, no body, and five legs; and then detaching one leg because it was "different". :P -- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 19:57, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- See invertebrate. The first sentence of the second paragraph says, "Invertebrates form a paraphyletic group." ScienceApe (talk) 23:14, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- See above note (I have removed the <small> tags). In Linnean taxonomy, non-vertebrate animal phyla included only two groups: "Vermes" and "Insecta", and they included a mishmash of organisms (again even including Volvox, which is under Plantae). When Lamarck introduced the formal group "Invertebrata", he divided them into "Mollusques", "Crustacés", "Arachnides", "Insectes", "Vers", "Radiaires", and "Polypes". All of which do not include a common ancestor. Thus these groupings are polyphyletic. These were the only instances where Invertebrata was treated as a formal group. In the modern sense, the term "invertebrate" is completely informal with a definition that has become simply "all metazoans, excluding Vertebrata". It is thus paraphyletic to vertebrates, provided that you accept a monophyletic Metazoa.

- And that article still needs a lot of work, which illustrates exactly how problematic the grouping is.-- OBSIDIAN†SOUL 02:21, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

It's important to distinguish between amphibia and amphibians. In modern biology amphibia names a monophyletic group which includes amphibians as well as reptiles, birds, and mammals. Similarly reptilia names a monophyletic group which includes reptiles, crocodilians, and birds.— Preceding unsigned comment added by Looie496 (talk • contribs) 00:47, 6 February 2012 (UTC)

Equation explanation

Can someone explain for me how to use this equation? 4π2r3/T2 = G(m1 + m2). Thanks!Pendragon5 (talk) 19:48, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

- It's a form of Newton's law of universal gravitation as it applies to a body in orbit. G is the Gravitational constant and m1 and m2 are the masses of two bodies, r is the distance between the centers of the bodies, π is 3.14159... and T is the orbital period (i.e. time for the two bodies to return to the same relative position). An alternative form of this same equation is at Orbital_period#Small_body_orbiting_a_central_body. --Jayron32 20:44, 5 February 2012 (UTC)

What is / sign, the one right in front of T stand for? And yes finally, this is the one i'm looking for. I just didn't understand it at first.Pendragon5 (talk) 20:57, 5 February 2012 (UTC)