Rohingya people: Difference between revisions

→Religion: No idea why that link was there |

→External links: fixed link |

||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http://www.rohingya.org/index.php |

*[http://www.rohingya.org/portal/index.php/rohingya-library/26-rohingya-history/75-the-muslim-rohingya-of-burma.html The Muslim “Rohingya” of Burma by Martin Smith 1995] ''Arakan Rohingya National Organisation'' 2006 |

||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rohingya People}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Rohingya People}} |

||

Revision as of 22:16, 23 August 2012

| Flag of the Rohingya Nation | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Burma (Arakan), Bangladesh, Malaysia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, India | |

| 800,000[1][2] | |

| 300,000[3] | |

| 200,000[4][5][6] | |

| 100,000[7] | |

| 24,000[8] | |

| Languages | |

| Rohingya language | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

The Rohingya (Burmese: ရိုဟင်ဂျာ) are a Muslim people who live in the Arakan region in western Myanmar (Burma). As of 2012, 800,000 Rohingya live in Myanmar. According to the UN, they are one of the most persecuted minorities in the world.[9] Many Rohingya have fled to ghettos and refugee camps in neighboring Bangladesh, and to areas along the Thai-Myanmar border.

Etymology

The origin of the term "Rohingya" is disputed. Some Rohingya historians like Khalilur Rahman contend that the term Rohingya is derived from Arabic word 'Rahma' meaning 'mercy'.[10] They trace the term back to a ship wreck in the 8th century CE. According to them, after the Arab ship wrecked near Ramree Island, Arab traders were ordered to be executed by the Arakanese king. Then, they shouted in their language, 'Rahma'. Hence, these people were called 'Raham'. Gradually it changed from Raham to Rhohang and finally to Rohingyas.[10][11] However, the claim was disputed by Jahiruddin Ahmed and Nazir Ahmed, former president and Secretary of Arakan Muslim Conference respectively.[10] They argued that ship wreck Muslims are currently called 'Thambu Kya' Muslims, and currently reside along the Arakan sea shore. If the term Rohingya was indeed derived because of that group of Muslims, "Thambu Kyas" would have been the first group to be known as Rohingyas. According to them, Rohingyas were descendants of inhabitants of Ruha in Afghanistan.[10] Another historian, MA Chowdhury argued that among the Muslim populations in Myanmar, the term 'Mrohaung' (Old Arakanese Kingdom) was corrupted to Rohang. And thus inhabitants of the region are called Rohingya.[10]

Burmese historians like Khin Maung Saw have claimed that the term Rohingya has never appeared in history before 1950s.[12] According to another historian, Dr. Maung Maung, there is no such word as Rohingya in 1824 census survey conducted by the British.[13] Historian Aye Chan from Kanda University of International Studies noted that the term Rohingya was created by descendants of Bengalis in 1950s who migrated into Arakan during the Colonial Era. He further argued that the term cannot be found in any historical source in any language before 1950s. However, he stated that it does not mean Muslim communities have not existed in Arakan before 1824.[14]

However, Arakan history expert Dr. Jacques P. Leider points out that the term Rooinga was in fact used in a late 18th century report published by the British Francis Buchanan-Hamilton.[15] In his 1799 article “A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire,” Buchanan-Hamilton stated: "I shall now add three dialects, spoken in the Burma Empire, but evidently derived from the language of the Hindu nation. The first is that spoken by the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan, and who call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan."[16] Leider also adds that the etymology of the word "does not say anything about politics." He adds that "You use this term for yourself as a political label to give yourself identity in the 20th century. Now how is this term used since the 1950s? It is clear that people who use it want to give this identity to the community that live there."[15]

Language

The Rohingya language is the modern written language of the Rohingya people of Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar). It is an Indo-European language and it's linguistically related to the Chittagonian language spoken in the southernmost part of Bangladesh bordering Burma. Rohingya scholars have successfully written the Rohingya language in different scripts such as Arabic, Hanifi, Urdu, Roman, and Burmese, where Hanifi is a newly developed alphabet derived from Arabic with the addition of four characters from Latin and Burmese.

More recently, a Latin alphabet has been developed, using all 26 English letters A to Z and two additional Latin letters Ç (for retroflex R) and Ñ (for nasal sound). To accurately represent Rohingya phonology, it also uses five accented vowels (áéíóú). It has been recognized by ISO with ISO 639-3 "rhg" code.[17]

History

Muslim settlements have existed in Arakan since the arrival of Arabs there in the 8th century CE. The direct descendants of Arab settlers are believed to live in central Arakan near Mrauk-U and Kyauktaw townships, rather than the Mayu frontier area, the present day area where a majority of Rohingya are populated, near Chittagong Division, Bangladesh.[18]

Kingdom of Mrauk U

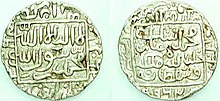

Early evidence of Bengali Muslim settlements in Arakan date back to the time of King Narameikhla (1430–1434) of Kingdom of Mrauk U. After 24 years of exile in Bengal, he regained control of the Arakanese throne in 1430 with military assistance from the Sultanate of Bengal. The Bengalis who came with him formed their own settlements in the region.[19][20] Narameikhla ceded some territory to the Sultan of Bengal and recognized his sovereignty over the areas. In recognition of his kingdom's vassal status, the kings of Arakan received Islamic titles and used the use of Bengali Islamic coinage within the kingdom. Narameikhla minted his own coins with Burmese characters on one side and Persian characters on the other.[20] Arakan's vassalage to Bengal was brief. After Sultan Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah's death in 1433, Narameikhla's successors repaid Bengal by occupying Ramu in 1437 and Chittagong in 1459. Arakan would hold Chittagong until 1666.[21][22]

Even after gaining independence from the Sultans of Bengal, the Arakanese kings continued the custom of maintaining Muslim titles.[23] The Buddhist kings compared themselves to Sultans and fashioned themselves after Mughal rulers. They also continued to employ Muslims in prestigious positions within the royal administration.[24] The Bengali Muslim population increased in the 17th century, as they were employed in a variety of workforces in Arakan. Some of them worked as Bengali, Persian and Arabic scribes in the Arakanese courts, which, despite remaining mostly Buddhist, adopted Islamic fashions from the neighbouring Sultanate of Bengal.[19] The Kamein/Kaman, who are regarded as one of the official ethnic groups of Burma, are descended from these Muslims.[25]

Burmese conquest

Following the Burmese conquest of Arakan in 1785, as many as 35,000 Arakanese people fled to the neighbouring Chittagong region of British Bengal in 1799 to avoid Burmese persecution and seek protection from British India.[26] The Burmese rulers executed thousands of Arakanese men and deported a considerable portion of the Arakanese population to central Burma, leaving Arakan as a scarcely populated area by the time the British occupied it.[27] According to an article on the "Burma Empire" published by the British Francis Buchanan-Hamilton in 1799, "the Mohammedans, who have long settled in Arakan," "call themselves Rooinga, or natives of Arakan."[16]

British colonial rule

Due to Arakan being scarcely populated by the time they occupied it, British policy encouraged Bengali inhabitants from adjacent regions to migrate into fertile valleys of Arakan as agriculturalists. The East India Company extended the Bengal administration to Arakan, thus there was no international boundary between Bengal and Arakan, and no restrictions on migration between the regions. In the early 19th century, thousands of Bengalis from the Chittagong region settled in Arakan seeking work opportunities.[27] In addition, thousands of Rakhine people from Arakan also settled in Bengal.[28][29]

The British census of 1891 reported 58,255 Muslims in Arakan. By 1911, the Muslim population had increased to 178,647.[30] The waves of migration were primarily due to the requirement of cheap labor from British India to work in the paddy fields. Immigrants from Bengal, mainly from the Chittagong region, "moved en masse into western townships of Arakan". To be sure, Indian immigration to Burma was a nationwide phenomenon, not just restricted to Arakan. Historian Thant Myint-U writes: "At the beginning of the 20th century, Indians were arriving in Burma at the rate of no less than a quarter million per year. The numbers rose steadily until the peak year of 1927, immigration reached 480,000 people, with Rangoon exceeding New York City as the greatest immigration port in the world. This was out of a total population of only 13 million; it was equivalent to the United Kingdom today taking 2 million people a year." By then, in most of the largest cities in Burma, Rangoon (Yangon), Akyab (Sittwe), Bassein (Pathein), Moulmein, the Indian immigrants formed a majority of the population. The Burmese under the British rule felt helpless, and reacted with a "racism that combined feelings of superiority and fear."[31]

The immigration's impact was particularly acute in Arakan, one of less populated regions. In 1939, the British authorities, who were wary of the long term animosity between the Rakhine Buddhists and the Rohingya Muslims, formed a special Investigation Commission led by James Ester and Tin Tut to study the issue of Muslim immigration into the Rakhine state. The commission recommended securing the border; however, with the onset of World War II, the British retreated from Arakan.[32]

World War II Japanese occupation

On 28 March 1942, some thousands of Muslims (about 5,000) in Minbya and Mrohaung Townships were killed by Rakhine nationalists and Karenni. On the other side, the Muslims from Northern Rakhine State massacred around 20,000 Arakanese including the Deputy Commissioner U Oo Kyaw Khaing who was killed while trying to settle the dispute.[32]

During World War II, Japanese forces invaded Burma, then under British colonial rule. The British forces retreated and in the power vacuum left behind, considerable violence erupted. This included communal violence between Buddhist Rakhine and Muslim Rohingya villagers. The period also witnessed violence between groups loyal to the British and Burmese nationalists. The British armed Muslim groups in northern Arakan to create a buffer zone from Japanese invasion when they retreated.[33]The Rohingya supported the Allies during the war and opposed the Japanese forces, assisting the Allies in reconnaissance.

The Japanese committed atrocities against thousands of Rohingya. They engaged in an orgy of rape, murder and torture.[34] In this period, some 22,000 Rohingya are believed to have crossed the border into Bengal, then part of British India, to escape the violence.[35][36]

40,000 Rohingya eventually fled to Chittagong after repeated massacres by the Burmese and Japanese forces.[37]

Post-war

The Mujahid party was founded by Rohingya elders who supported Jihad movement in northern Arakan in 1947.[38] The aim of the Mujahid party was to create a Muslim Autonomous state in Arakan. They were much more active before the 1962 coup d'etat by General Ne Win. Ne Win carried out some military operations targeting them over a period of two decades. The prominent one was "Operation King Dragon" which took place in 1978; as a result, many Muslims in the region fled to neighboring country Bangladesh as refugees. Nevertheless, the Burmese mujahideen (Islamic militants) are still active within the remote areas of Arakan.[39] The associations of Burmese mujahideen with Bangladeshi mujahideen were significant, but they have extended their networks to the international level and countries, during the recent years. They collect donations, and receive religious military training outside of Burma.[40] In addition to Bangladesh, a large number of Rohingya have also migrated to Karachi, Pakistan.[6]

Burmese Junta

The military Junta which ruled Burma for half a century, relied heavily on Burmese nationalism and Theravada Buddhism to bolster its rule, and, in opinion of US government experts, heavily discriminated against minorities like the Rohingya, Chinese people like the Kokang people, and Panthay (Chinese Muslims). But even some pro-democracy dissidents from Burma's ethnic Burman majority refuse to acknowledge the Rohingyas as compatriots.[41][42]

Successive Burmese governments have been accused of provoking riots against ethnic minorities like the Rohingya and Chinese.[43]

2012 Rakhine State riots

The 2012 Rakhine State riots are a series of ongoing conflicts between Rohingya Muslims and ethnic Rakhine in northern Rakhine State, Myanmar. The riots came after weeks of sectarian disputes and have been condemned by most people on both sides of the conflict.[44] The immediate cause of the riots is unclear, with many commentators citing the killing of ten Burmese Muslims by ethnic Rakhine after the rape and murder of a Rakhine woman as the main cause. Over three hundred houses and a number of public buildings have been razed. According to Tun Khin, the President of the Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK, as of 28 June, 650 Rohingyas have been killed, 1,200 are missing, and more than 80,000 have been displaced.[45] According to the Myanmar authorities, the violence, between ethnic Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims, left 78 people dead, 87 injured, and thousands of homes destroyed. It also displaced more than 52,000 people.[46]

The government has responded by imposing curfews and by deploying troops in the regions. On June 10, state of emergency was declared in Rakhine, allowing military to participate in administration of the region.[47][48]The Burmese army and police have been accused of targeting Rohingya Muslims through mass arrests and arbitrary violence.[45][49] A number of monks' organizations that played vital role in Burma's struggle for democracy have taken measures to block any humanitarian assistance to the Rohingya community.[50] In July 2012, the Myanmar Government asserted that the Rohingya minority group, classified as stateless Bengali Muslims from Bangladesh since 1982, are not included in their more than 130 ethnic races and have no claim to Myanmar citizenship.[51]

Religion

The Rohingya people practice Sunni Islam with elements of Sufi worship. Because the government restricts educational opportunities for them, many pursue fundamental Islamic studies as their only educational option. Mosques and religious schools are present in most villages. Traditionally, men pray in congregations and women pray at home.

Human rights violations & refugees

The Rohingya people have been described as “among the world’s least wanted”[52] and “one of the world’s most persecuted minorities.”[53] They have been stripped of their citizenship since a 1982 citizenship law.[54] They are not allowed to travel without official permission, are banned from owning land and are required to sign a commitment to have not more than two children.[54]

According to Amnesty International, the Muslim Rohingya people have continued to suffer from human rights violations under the Burmese junta since 1978, and many have fled to neighboring Bangladesh as a result:.[55]

"The Rohingyas’ freedom of movement is severely restricted and the vast majority of them have effectively been denied Burma citizenship. They are also subjected to various forms of extortion and arbitrary taxation; land confiscation; forced eviction and house destruction; and financial restrictions on marriage. Rohingyas continue to be used as forced labourers on roads and at military camps, although the amount of forced labour in northern Rakhine State has decreased over the last decade."

"In 1978 over 200,000 Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh, following the ‘Nagamin’ (‘Dragon King’) operation of the Myanmar army. Officially this campaign aimed at "scrutinising each individual living in the state, designating citizens and foreigners in accordance with the law and taking actions against foreigners who have filtered into the country illegally." This military campaign directly targeted civilians, and resulted in widespread killings, rape and destruction of mosques and further religious persecution."

"During 1991-92 a new wave of over a quarter of a million Rohingyas fled to Bangladesh. They reported widespread forced labour, as well as summary executions, torture, and rape. Rohingyas were forced to work without pay by the Burmese army on infrastructure and economic projects, often under harsh conditions. Many other human rights violations occurred in the context of forced labour of Rohingya civilians by the security forces."

As of 2005, the UNHCR had been assisting with the repatriation of Rohingya from Bangladesh, but allegations of human rights abuses in the refugee camps have threatened this effort.[56]

Despite earlier efforts by the UN, the vast majority of Rohingya refugees have remained in Bangladesh, unable to return because of the negative attitude of the ruling regime in Myanmar. Now they are facing problems in Bangladesh as well where they do not receive support from the government any longer.[57] In February 2009, many Rohingya refugees were rescued by Acehnese sailors in the Strait of Malacca, after 21 days at sea.[58]

Over the years, thousands of Rohingya have fled to Thailand also. There are roughly 111,000 refugees housed in 9 camps along the Thai-Myanmar border. There have been charges that groups of them have been shipped and towed out to open sea from Thailand, and left there. In February 2009 there was evidence of the Thai army towing a boatload of 190 Rohingya refugees out to sea. A group of refugees rescued by Indonesian authorities also in February 2009 told harrowing stories of being captured and beaten by the Thai military, and then abandoned at open sea. By the end of February there were reports of a group of 5 boats were towed out to open sea, of which 4 boats sank in a storm, and 1 boat washed up on the shore. February 12, 2009 Thailand's prime minister Abhisit Vejjajiva said there were "some instances" in which Rohingya people were pushed out to sea.

"There are attempts, I think, to let these people drift to other shores. [...] when these practices do occur, it is done on the understanding that there is enough food and water supplied. [...] It's not clear whose work it is [...] but if I have the evidence who exactly did this I will bring them to account."[59]

The prime minister said he regretted "any losses", and was working on rectifying the problem.

Steps to repatriate Rohingya began in 2005. In 2009 Bangladesh announced it will repatriate around 9,000 Rohingya living in refugee camps in the country back to Burma, after a meeting with Burmese diplomats.[60][61]

In October 16, 2011, the new government of Burma agreed to take back registered Rohingya refugees.[62][63]

See also

Notes

- ^ Macan-Markar, Marwaan (June 15, 2012). "Ethnic Cleansing of Muslim Minority in Myanmar?". [Inter Press Service]]. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ 729,000 (United Nations estimate 2009)

- ^ "Myanmar Rohingya refugees call for Suu Kyi's help". Agence France-Presse. June 13, 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Homeless in Karachi - Outlook India

- ^ SRI On-Site Action Alert: Rohingya Refugees of Burma and UNHCR’s repatriation program - Burma Library

- ^ a b From South to South: Refugees as Migrants: The Rohingya in Pakistan

- ^ Husain, Irfan (30 July 2012). "Karma and killings in Myanmar". Dawn. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- ^ Flores, Jamil Maidan (July 16, 2012). "The Lady's Dilemma Over Myanmar's Rohingya". Jakarta Globe. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ "Myanmar, Bangladesh leaders 'to discuss Rohingya'". AFP. 2012-06-29.

- ^ a b c d e (MA Chowdhury 1995, pp. 7–8)

- ^ (Khin Maung Saw 1993, pp. 93)

- ^ (Khin Maung Saw 1993, p. 90)

- ^ KYAW ZWA MOE. "Why is Western Burma Burning?". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ (Aye Chan 2005, p. 396)

- ^ a b Leider, Jacques P. (July 9, 2012). "Interview: History Behind Arakan State Conflict". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ a b Buchanan-Hamilton, Francis (1799). "A Comparative Vocabulary of Some of the Languages Spoken in the Burma Empire" (PDF). Asiatic Researches. 5. The Asiatic Society: 219–240. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ ISO 639 Code Tables - SIL International

- ^ (Aye Chan 2005, p. 397)

- ^ a b (Aye Chan 2005, p. 398)

- ^ a b Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Phayre 1883: 78

- ^ Harvey 1925: 140–141

- ^ Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 23–4. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 24. ISBN 0739103563. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Maung San Da (2005). History of Ethnic Kaman (Burmese). Yangon.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ (Aye Chan 2005, pp. 398–9)

- ^ a b (Aye Chan 2005, p. 399)

- ^ "Rakhine people in Bangladesh". Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ "Rakhine people who speak Marma". Retrieved 2010-07-22.

- ^ (Aye Chan 2005, p. 401)

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 185–187

- ^ a b Kyaw Zan Tha, MA (2008). "Background of Rohingya Problem": 1.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Field-Marshal Viscount William Slim (2009). Defeat Into Victory: Battling Japan in Burma and India, 1942-1945. London: Pan. ISBN 0330509977.

- ^ Kurt Jonassohn (1999). Genocide and gross human rights violations: in comparative perspective. Transaction Publishers. p. 263. ISBN 0765804174. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Howard Adelman (2008). Protracted displacement in Asia: no place to call home. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 86. ISBN 0754672387. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (Organization) (2000). Burma/Bangladesh: Burmese refugees in Bangladesh: still no durable solution. Human Rights Watch. p. 6. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Asian profile, Volume 21. Asian Research Service. 1993. p. 312. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ Bilveer Singh (2007). The Talibanization of Southeast Asia: Losing the War on Terror to Islamist Extremists. p. 42. ISBN 0275999955.

- ^ Global Muslim News (Issue 14) July-Sept 1996, Nida'ul Islam magazine.

- ^ Rohingyas trained in different Al-Qaeda and Taliban camps in Afghanistan By William Gomes - Bangladesh, Apr 01 2009, .Asian Tribune.

- ^ Violence Throws Spotlight on Rohingya

- ^ Moshahida Sultana Ritu (12 July 2012). "Ethnic Cleansing in Myanmar". New York Times. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- ^ Karl R. DeRouen, Uk Heo (2007). Civil wars of the world: major conflicts since World War II. ABC-CLIO. p. 530. ISBN 1851099190. Retrieved 12 April 2011.

- ^ "Four killed as Rohingya Muslims riot in Myanmar: government". Reuters. June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Hindstorm, Hanna (28 June 2012). "Burmese authorities targeting Rohingyas, UK parliament told". Democratic Voice of Burma. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ "UN refugee agency redeploys staff to address humanitarian needs in Myanmar". UN News. June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ Linn Htet (June 11, 2012). "အေရးေပၚအေျခအေန ေၾကညာခ်က္ ႏုိင္ငံေရးသမားမ်ား ေထာက္ခံ". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ Keane, Fergal (June 11, 2012). "Old tensions bubble in Burma". BBC News Online. Retrieved 2012-06-11.

- ^ "UN focuses on Myanmar amid Muslim plight". PressTV. July 13, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- ^ Hindstorm, Hanna (25 July 2012). "Burma's monks call for Muslim community to be shunned". The Independent. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ . 1 August 2012 http://www.thehindu.com/news/international/article3703383.ece.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|Title=ignored (|title=suggested) (help) - ^ Mark Dummett (18 February 2010). "Bangladesh accused of 'crackdown' on Rohingya refugees". BBC. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Myanmar, Bangladesh leaders 'to discuss Rohingya'". AFP. 25 June 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ a b Jonathan Head (5 February 2009). "What drive the Rohingya to sea?". BBC. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Myanmar - The Rohingya Minority: Fundamental Rights Denied, Amnesty International, 2004.

- ^ "UNHCR threatens to wind up Bangladesh operations". New Age BDNEWS, Dhaka. 2005-05-21. Retrieved 2007-04-25.

- ^ Burmese exiles in desperate conditions

- ^ Kompas.

- ^ Rivers, Dan (February 12, 2009). Thai PM admits boat people pushed out to sea. CNN.

- ^ Press Trust of India (December 29, 2009). "Myanmar to repatriate 9,000 Muslim refugees from B'desh". Zee News.

- ^ Staff Correspondent (December 30, 2009). "Myanmar to take back 9,000 Rohingyas soon". The Daily Star (Bangladesh).

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Myanmar to 'take back' Rohingya refugees". The Daily Star. October 16, 2011.

- ^ Manchester Guardian: Little help for the persecuted Rohingya of Burma http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/belief/2011/dec/01/rohingya-burma?INTCMP=SRCH

References

- Khin Maung Saw (1993). "Khin Maung Saw on Rohingya" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - MA Chowdhury (1995). The advent of Islam in Arakan and the Rohingyas (PDF). Chittagong University. Arakan Historical Society. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Aye Chan (2005). "The Development of a Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar)" (PDF). SOAS. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Myanmar, The Rohingya Minority: Fundamental Rights Denied". Amnesty International. Retrieved August 2005.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Amnesty International (English)

- The Burmanization of Myanmar's Muslims, the acculturation of the Muslims in Burma including Arakan, Jean A. Berlie, White Lotus Press editor, Bangkok, Thailand, published in 2008. ISBN 9744801263, 9789744801265.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps--Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6, 0-374-16342-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

External links

- The Muslim “Rohingya” of Burma by Martin Smith 1995 Arakan Rohingya National Organisation 2006