Immune system: Difference between revisions

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) m Tagging page with PC1 protection template. (beta framework) |

→External links: Library resources box |

||

| Line 204: | Line 204: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Library resources box |

|||

|onlinebooks=yes |

|||

|by=no |

|||

|lcheading=Immune system |

|||

|label=Immune system |

|||

}} |

|||

*[http://uhaweb.hartford.edu/BUGL/immune.htm Immune System] – from the [[University of Hartford]] (high school/undergraduate level) |

*[http://uhaweb.hartford.edu/BUGL/immune.htm Immune System] – from the [[University of Hartford]] (high school/undergraduate level) |

||

*[http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/book/immunol-sta.htm Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook] – from the [[University of South Carolina]] School of Medicine (undergraduate level) |

*[http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/book/immunol-sta.htm Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook] – from the [[University of South Carolina]] School of Medicine (undergraduate level) |

||

Revision as of 01:11, 11 April 2013

The immune system is a system of biological structures and processes within an organism that protects against disease. To function properly, an immune system must detect a wide variety of agents, from viruses to parasitic worms, and distinguish them from the organism's own healthy tissue.

Pathogens can rapidly evolve and adapt, and thereby avoid detection and neutralization by the immune system, however, multiple defense mechanisms have also evolved to recognize and neutralize pathogens. Even simple unicellular organisms such as bacteria possess a rudimentary immune system, in the form of enzymes that protect against bacteriophage infections. Other basic immune mechanisms evolved in ancient eukaryotes and remain in their modern descendants, such as plants and insects. These mechanisms include phagocytosis, antimicrobial peptides called defensins, and the complement system. Jawed vertebrates, including humans, have even more sophisticated defense mechanisms,[1] including the ability to adapt over time to recognize specific pathogens more efficiently. Adaptive (or acquired) immunity creates immunological memory after an initial response to a specific pathogen, leading to an enhanced response to subsequent encounters with that same pathogen. This process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination.

Disorders of the immune system can result in autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and cancer.[2][3] Immunodeficiency occurs when the immune system is less active than normal, resulting in recurring and life-threatening infections. In humans, immunodeficiency can either be the result of a genetic disease such as severe combined immunodeficiency, acquired conditions such as HIV/AIDS, or the use of immunosuppressive medication. In contrast, autoimmunity results from a hyperactive immune system attacking normal tissues as if they were foreign organisms. Common autoimmune diseases include Hashimoto's thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus type 1, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunology covers the study of all aspects of the immune system.

History of immunology

Immunology is a science that examines the structure and function of the immune system. It originates from medicine and early studies on the causes of immunity to disease. The earliest known reference to immunity was during the plague of Athens in 430 BC. Thucydides noted that people who had recovered from a previous bout of the disease could nurse the sick without contracting the illness a second time.[4] In the 18th century, Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis made experiments with scorpion venom and observed that certain dogs and mice were immune to this venom.[5] This and other observations of acquired immunity were later exploited by Louis Pasteur in his development of vaccination and his proposed germ theory of disease.[6] Pasteur's theory was in direct opposition to contemporary theories of disease, such as the miasma theory. It was not until Robert Koch's 1891 proofs, for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905, that microorganisms were confirmed as the cause of infectious disease.[7] Viruses were confirmed as human pathogens in 1901, with the discovery of the yellow fever virus by Walter Reed.[8]

Immunology made a great advance towards the end of the 19th century, through rapid developments, in the study of humoral immunity and cellular immunity.[9] Particularly important was the work of Paul Ehrlich, who proposed the side-chain theory to explain the specificity of the antigen-antibody reaction; his contributions to the understanding of humoral immunity were recognized by the award of a Nobel Prize in 1908, which was jointly awarded to the founder of cellular immunology, Elie Metchnikoff.[10]

Layered defense

The immune system protects organisms from infection with layered defenses of increasing specificity. In simple terms, physical barriers prevent pathogens such as bacteria and viruses from entering the organism. If a pathogen breaches these barriers, the innate immune system provides an immediate, but non-specific response. Innate immune systems are found in all plants and animals.[11] If pathogens successfully evade the innate response, vertebrates possess a second layer of protection, the adaptive immune system, which is activated by the innate response. Here, the immune system adapts its response during an infection to improve its recognition of the pathogen. This improved response is then retained after the pathogen has been eliminated, in the form of an immunological memory, and allows the adaptive immune system to mount faster and stronger attacks each time this pathogen is encountered.[12]

| Innate immune system | Adaptive immune system |

|---|---|

| Response is non-specific | Pathogen and antigen specific response |

| Exposure leads to immediate maximal response | Lag time between exposure and maximal response |

| Cell-mediated and humoral components | Cell-mediated and humoral components |

| No immunological memory | Exposure leads to immunological memory |

| Found in nearly all forms of life | Found only in jawed vertebrates |

Both innate and adaptive immunity depend on the ability of the immune system to distinguish between self and non-self molecules. In immunology, self molecules are those components of an organism's body that can be distinguished from foreign substances by the immune system.[13] Conversely, non-self molecules are those recognized as foreign molecules. One class of non-self molecules are called antigens (short for antibody generators) and are defined as substances that bind to specific immune receptors and elicit an immune response.[14]

Surface barriers

Several barriers protect organisms from infection, including mechanical, chemical, and biological barriers. The waxy cuticle of many leaves, the exoskeleton of insects, the shells and membranes of externally deposited eggs, and skin are examples of mechanical barriers that are the first line of defense against infection.[14] However, as organisms cannot be completely sealed against their environments, other systems act to protect body openings such as the lungs, intestines, and the genitourinary tract. In the lungs, coughing and sneezing mechanically eject pathogens and other irritants from the respiratory tract. The flushing action of tears and urine also mechanically expels pathogens, while mucus secreted by the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract serves to trap and entangle microorganisms.[15]

Chemical barriers also protect against infection. The skin and respiratory tract secrete antimicrobial peptides such as the β-defensins.[16] Enzymes such as lysozyme and phospholipase A2 in saliva, tears, and breast milk are also antibacterials.[17][18] Vaginal secretions serve as a chemical barrier following menarche, when they become slightly acidic, while semen contains defensins and zinc to kill pathogens.[19][20] In the stomach, gastric acid and proteases serve as powerful chemical defenses against ingested pathogens.

Within the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, commensal flora serve as biological barriers by competing with pathogenic bacteria for food and space and, in some cases, by changing the conditions in their environment, such as pH or available iron.[21] This reduces the probability that pathogens will reach sufficient numbers to cause illness. However, since most antibiotics non-specifically target bacteria and do not affect fungi, oral antibiotics can lead to an "overgrowth" of fungi and cause conditions such as a vaginal candidiasis (a yeast infection).[22] There is good evidence that re-introduction of probiotic flora, such as pure cultures of the lactobacilli normally found in unpasteurized yogurt, helps restore a healthy balance of microbial populations in intestinal infections in children and encouraging preliminary data in studies on bacterial gastroenteritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, urinary tract infection and post-surgical infections.[23][24][25]

Innate immune system

Microorganisms or toxins that successfully enter an organism encounter the cells and mechanisms of the innate immune system. The innate response is usually triggered when microbes are identified by pattern recognition receptors, which recognize components that are conserved among broad groups of microorganisms,[26] or when damaged, injured or stressed cells send out alarm signals, many of which (but not all) are recognized by the same receptors as those that recognize pathogens.[27] Innate immune defenses are non-specific, meaning these systems respond to pathogens in a generic way.[14] This system does not confer long-lasting immunity against a pathogen. The innate immune system is the dominant system of host defense in most organisms.[11]

Humoral and chemical barriers

Inflammation

Inflammation is one of the first responses of the immune system to infection.[28] The symptoms of inflammation are redness, swelling, heat, and pain, which are caused by increased blood flow into tissue. Inflammation is produced by eicosanoids and cytokines, which are released by injured or infected cells. Eicosanoids include prostaglandins that produce fever and the dilation of blood vessels associated with inflammation, and leukotrienes that attract certain white blood cells (leukocytes).[29][30] Common cytokines include interleukins that are responsible for communication between white blood cells; chemokines that promote chemotaxis; and interferons that have anti-viral effects, such as shutting down protein synthesis in the host cell.[31] Growth factors and cytotoxic factors may also be released. These cytokines and other chemicals recruit immune cells to the site of infection and promote healing of any damaged tissue following the removal of pathogens.[32]

Complement system

The complement system is a biochemical cascade that attacks the surfaces of foreign cells. It contains over 20 different proteins and is named for its ability to "complement" the killing of pathogens by antibodies. Complement is the major humoral component of the innate immune response.[33][34] Many species have complement systems, including non-mammals like plants, fish, and some invertebrates.[35]

In humans, this response is activated by complement binding to antibodies that have attached to these microbes or the binding of complement proteins to carbohydrates on the surfaces of microbes. This recognition signal triggers a rapid killing response.[36] The speed of the response is a result of signal amplification that occurs following sequential proteolytic activation of complement molecules, which are also proteases. After complement proteins initially bind to the microbe, they activate their protease activity, which in turn activates other complement proteases, and so on. This produces a catalytic cascade that amplifies the initial signal by controlled positive feedback.[37] The cascade results in the production of peptides that attract immune cells, increase vascular permeability, and opsonize (coat) the surface of a pathogen, marking it for destruction. This deposition of complement can also kill cells directly by disrupting their plasma membrane.[33]

Cellular barriers

Leukocytes (white blood cells) act like independent, single-celled organisms and are the second arm of the innate immune system.[14] The innate leukocytes include the phagocytes (macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells), mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and natural killer cells. These cells identify and eliminate pathogens, either by attacking larger pathogens through contact or by engulfing and then killing microorganisms.[35] Innate cells are also important mediators in the activation of the adaptive immune system.[12]

Phagocytosis is an important feature of cellular innate immunity performed by cells called 'phagocytes' that engulf, or eat, pathogens or particles. Phagocytes generally patrol the body searching for pathogens, but can be called to specific locations by cytokines.[14] Once a pathogen has been engulfed by a phagocyte, it becomes trapped in an intracellular vesicle called a phagosome, which subsequently fuses with another vesicle called a lysosome to form a phagolysosome. The pathogen is killed by the activity of digestive enzymes or following a respiratory burst that releases free radicals into the phagolysosome.[38][39] Phagocytosis evolved as a means of acquiring nutrients, but this role was extended in phagocytes to include engulfment of pathogens as a defense mechanism.[40] Phagocytosis probably represents the oldest form of host defense, as phagocytes have been identified in both vertebrate and invertebrate animals.[41]

Neutrophils and macrophages are phagocytes that travel throughout the body in pursuit of invading pathogens.[42] Neutrophils are normally found in the bloodstream and are the most abundant type of phagocyte, normally representing 50% to 60% of the total circulating leukocytes.[43] During the acute phase of inflammation, particularly as a result of bacterial infection, neutrophils migrate toward the site of inflammation in a process called chemotaxis, and are usually the first cells to arrive at the scene of infection. Macrophages are versatile cells that reside within tissues and produce a wide array of chemicals including enzymes, complement proteins, and regulatory factors such as interleukin 1.[44] Macrophages also act as scavengers, ridding the body of worn-out cells and other debris, and as antigen-presenting cells that activate the adaptive immune system.[12]

Dendritic cells (DC) are phagocytes in tissues that are in contact with the external environment; therefore, they are located mainly in the skin, nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines.[45] They are named for their resemblance to neuronal dendrites, as both have many spine-like projections, but dendritic cells are in no way connected to the nervous system. Dendritic cells serve as a link between the bodily tissues and the innate and adaptive immune systems, as they present antigen to T cells, one of the key cell types of the adaptive immune system.[45]

Mast cells reside in connective tissues and mucous membranes, and regulate the inflammatory response.[46] They are most often associated with allergy and anaphylaxis.[43] Basophils and eosinophils are related to neutrophils. They secrete chemical mediators that are involved in defending against parasites and play a role in allergic reactions, such as asthma.[47] Natural killer (NK cells) cells are leukocytes that attack and destroy tumor cells, or cells that have been infected by viruses.[48]

Adaptive immune system

The adaptive immune system evolved in early vertebrates and allows for a stronger immune response as well as immunological memory, where each pathogen is "remembered" by a signature antigen.[49] The adaptive immune response is antigen-specific and requires the recognition of specific "non-self" antigens during a process called antigen presentation. Antigen specificity allows for the generation of responses that are tailored to specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells. The ability to mount these tailored responses is maintained in the body by "memory cells". Should a pathogen infect the body more than once, these specific memory cells are used to quickly eliminate it.

Lymphocytes

The cells of the adaptive immune system are special types of leukocytes, called lymphocytes. B cells and T cells are the major types of lymphocytes and are derived from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow.[35] B cells are involved in the humoral immune response, whereas T cells are involved in cell-mediated immune response.

Both B cells and T cells carry receptor molecules that recognize specific targets. T cells recognize a "non-self" target, such as a pathogen, only after antigens (small fragments of the pathogen) have been processed and presented in combination with a "self" receptor called a major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule. There are two major subtypes of T cells: the killer T cell and the helper T cell. Killer T cells only recognize antigens coupled to Class I MHC molecules, while helper T cells only recognize antigens coupled to Class II MHC molecules. These two mechanisms of antigen presentation reflect the different roles of the two types of T cell. A third, minor subtype are the γδ T cells that recognize intact antigens that are not bound to MHC receptors.[50]

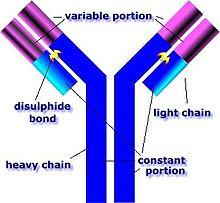

In contrast, the B cell antigen-specific receptor is an antibody molecule on the B cell surface, and recognizes whole pathogens without any need for antigen processing. Each lineage of B cell expresses a different antibody, so the complete set of B cell antigen receptors represent all the antibodies that the body can manufacture.[35]

Killer T cells

Killer T cells are a sub-group of T cells that kill cells that are infected with viruses (and other pathogens), or are otherwise damaged or dysfunctional.[51] As with B cells, each type of T cell recognizes a different antigen. Killer T cells are activated when their T cell receptor (TCR) binds to this specific antigen in a complex with the MHC Class I receptor of another cell. Recognition of this MHC:antigen complex is aided by a co-receptor on the T cell, called CD8. The T cell then travels throughout the body in search of cells where the MHC I receptors bear this antigen. When an activated T cell contacts such cells, it releases cytotoxins, such as perforin, which form pores in the target cell's plasma membrane, allowing ions, water and toxins to enter. The entry of another toxin called granulysin (a protease) induces the target cell to undergo apoptosis.[52] T cell killing of host cells is particularly important in preventing the replication of viruses. T cell activation is tightly controlled and generally requires a very strong MHC/antigen activation signal, or additional activation signals provided by "helper" T cells (see below).[52]

Helper T cells

Helper T cells regulate both the innate and adaptive immune responses and help determine which immune responses the body makes to a particular pathogen.[53][54] These cells have no cytotoxic activity and do not kill infected cells or clear pathogens directly. They instead control the immune response by directing other cells to perform these tasks.

Helper T cells express T cell receptors (TCR) that recognize antigen bound to Class II MHC molecules. The MHC:antigen complex is also recognized by the helper cell's CD4 co-receptor, which recruits molecules inside the T cell (e.g., Lck) that are responsible for the T cell's activation. Helper T cells have a weaker association with the MHC:antigen complex than observed for killer T cells, meaning many receptors (around 200–300) on the helper T cell must be bound by an MHC:antigen in order to activate the helper cell, while killer T cells can be activated by engagement of a single MHC:antigen molecule. Helper T cell activation also requires longer duration of engagement with an antigen-presenting cell.[55] The activation of a resting helper T cell causes it to release cytokines that influence the activity of many cell types. Cytokine signals produced by helper T cells enhance the microbicidal function of macrophages and the activity of killer T cells.[14] In addition, helper T cell activation causes an upregulation of molecules expressed on the T cell's surface, such as CD40 ligand (also called CD154), which provide extra stimulatory signals typically required to activate antibody-producing B cells.[56]

γδ T cells

γδ T cells possess an alternative T cell receptor (TCR) as opposed to CD4+ and CD8+ (αβ) T cells and share the characteristics of helper T cells, cytotoxic T cells and NK cells. The conditions that produce responses from γδ T cells are not fully understood. Like other 'unconventional' T cell subsets bearing invariant TCRs, such as CD1d-restricted Natural Killer T cells, γδ T cells straddle the border between innate and adaptive immunity.[57] On one hand, γδ T cells are a component of adaptive immunity as they rearrange TCR genes to produce receptor diversity and can also develop a memory phenotype. On the other hand, the various subsets are also part of the innate immune system, as restricted TCR or NK receptors may be used as pattern recognition receptors. For example, large numbers of human Vγ9/Vδ2 T cells respond within hours to common molecules produced by microbes, and highly restricted Vδ1+ T cells in epithelia respond to stressed epithelial cells.[50]

B lymphocytes and antibodies

A B cell identifies pathogens when antibodies on its surface bind to a specific foreign antigen.[59] This antigen/antibody complex is taken up by the B cell and processed by proteolysis into peptides. The B cell then displays these antigenic peptides on its surface MHC class II molecules. This combination of MHC and antigen attracts a matching helper T cell, which releases lymphokines and activates the B cell.[60] As the activated B cell then begins to divide, its offspring (plasma cells) secrete millions of copies of the antibody that recognizes this antigen. These antibodies circulate in blood plasma and lymph, bind to pathogens expressing the antigen and mark them for destruction by complement activation or for uptake and destruction by phagocytes. Antibodies can also neutralize challenges directly, by binding to bacterial toxins or by interfering with the receptors that viruses and bacteria use to infect cells.[61]

Alternative adaptive immune system

Although the classical molecules of the adaptive immune system (e.g., antibodies and T cell receptors) exist only in jawed vertebrates, a distinct lymphocyte-derived molecule has been discovered in primitive jawless vertebrates, such as the lamprey and hagfish. These animals possess a large array of molecules called variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs) that, like the antigen receptors of jawed vertebrates, are produced from only a small number (one or two) of genes. These molecules are believed to bind pathogenic antigens in a similar way to antibodies, and with the same degree of specificity.[62]

Immunological memory

When B cells and T cells are activated and begin to replicate, some of their offspring become long-lived memory cells. Throughout the lifetime of an animal, these memory cells remember each specific pathogen encountered and can mount a strong response if the pathogen is detected again. This is "adaptive" because it occurs during the lifetime of an individual as an adaptation to infection with that pathogen and prepares the immune system for future challenges. Immunological memory can be in the form of either passive short-term memory or active long-term memory.

Passive memory

Newborn infants have no prior exposure to microbes and are particularly vulnerable to infection. Several layers of passive protection are provided by the mother. During pregnancy, a particular type of antibody, called IgG, is transported from mother to baby directly across the placenta, so human babies have high levels of antibodies even at birth, with the same range of antigen specificities as their mother.[63] Breast milk or colostrum also contains antibodies that are transferred to the gut of the infant and protect against bacterial infections until the newborn can synthesize its own antibodies.[64] This is passive immunity because the fetus does not actually make any memory cells or antibodies—it only borrows them. This passive immunity is usually short-term, lasting from a few days up to several months. In medicine, protective passive immunity can also be transferred artificially from one individual to another via antibody-rich serum.[65]

Active memory and immunization

Long-term active memory is acquired following infection by activation of B and T cells. Active immunity can also be generated artificially, through vaccination. The principle behind vaccination (also called immunization) is to introduce an antigen from a pathogen in order to stimulate the immune system and develop specific immunity against that particular pathogen without causing disease associated with that organism.[14] This deliberate induction of an immune response is successful because it exploits the natural specificity of the immune system, as well as its inducibility. With infectious disease remaining one of the leading causes of death in the human population, vaccination represents the most effective manipulation of the immune system mankind has developed.[35][66]

Most viral vaccines are based on live attenuated viruses, while many bacterial vaccines are based on acellular components of micro-organisms, including harmless toxin components.[14] Since many antigens derived from acellular vaccines do not strongly induce the adaptive response, most bacterial vaccines are provided with additional adjuvants that activate the antigen-presenting cells of the innate immune system and maximize immunogenicity.[67]

Disorders of human immunity

The immune system is a remarkably effective structure that incorporates specificity, inducibility and adaptation. Failures of host defense do occur, however, and fall into three broad categories: immunodeficiencies, autoimmunity, and hypersensitivities.

Immunodeficiencies

Immunodeficiencies occur when one or more of the components of the immune system are inactive. The ability of the immune system to respond to pathogens is diminished in both the young and the elderly, with immune responses beginning to decline at around 50 years of age due to immunosenescence.[68][69] In developed countries, obesity, alcoholism, and drug use are common causes of poor immune function.[69] However, malnutrition is the most common cause of immunodeficiency in developing countries.[69] Diets lacking sufficient protein are associated with impaired cell-mediated immunity, complement activity, phagocyte function, IgA antibody concentrations, and cytokine production. Additionally, the loss of the thymus at an early age through genetic mutation or surgical removal results in severe immunodeficiency and a high susceptibility to infection.[70]

Immunodeficiencies can also be inherited or 'acquired'.[14] Chronic granulomatous disease, where phagocytes have a reduced ability to destroy pathogens, is an example of an inherited, or congenital, immunodeficiency. AIDS and some types of cancer cause acquired immunodeficiency.[71][72]

Autoimmunity

Overactive immune responses comprise the other end of immune dysfunction, particularly the autoimmune disorders. Here, the immune system fails to properly distinguish between self and non-self, and attacks part of the body. Under normal circumstances, many T cells and antibodies react with "self" peptides.[73] One of the functions of specialized cells (located in the thymus and bone marrow) is to present young lymphocytes with self antigens produced throughout the body and to eliminate those cells that recognize self-antigens, preventing autoimmunity.[59]

Hypersensitivity

Hypersensitivity is an immune response that damages the body's own tissues. They are divided into four classes (Type I – IV) based on the mechanisms involved and the time course of the hypersensitive reaction. Type I hypersensitivity is an immediate or anaphylactic reaction, often associated with allergy. Symptoms can range from mild discomfort to death. Type I hypersensitivity is mediated by IgE, which triggers degranulation of mast cells and basophils when cross-linked by antigen.[74] Type II hypersensitivity occurs when antibodies bind to antigens on the patient's own cells, marking them for destruction. This is also called antibody-dependent (or cytotoxic) hypersensitivity, and is mediated by IgG and IgM antibodies.[74] Immune complexes (aggregations of antigens, complement proteins, and IgG and IgM antibodies) deposited in various tissues trigger Type III hypersensitivity reactions.[74] Type IV hypersensitivity (also known as cell-mediated or delayed type hypersensitivity) usually takes between two and three days to develop. Type IV reactions are involved in many autoimmune and infectious diseases, but may also involve contact dermatitis (poison ivy). These reactions are mediated by T cells, monocytes, and macrophages.[74]

Other mechanisms

It is likely that a multicomponent, adaptive immune system arose with the first vertebrates, as invertebrates do not generate lymphocytes or an antibody-based humoral response.[1] Many species, however, utilize mechanisms that appear to be precursors of these aspects of vertebrate immunity. Immune systems appear even in the structurally most simple forms of life, with bacteria using a unique defense mechanism, called the restriction modification system to protect themselves from viral pathogens, called bacteriophages.[75] Prokaryotes also possess acquired immunity, through a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of phage that they have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block virus replication through a form of RNA interference.[76][77]

Pattern recognition receptors are proteins used by nearly all organisms to identify molecules associated with pathogens. Antimicrobial peptides called defensins are an evolutionarily conserved component of the innate immune response found in all animals and plants, and represent the main form of invertebrate systemic immunity.[1] The complement system and phagocytic cells are also used by most forms of invertebrate life. Ribonucleases and the RNA interference pathway are conserved across all eukaryotes, and are thought to play a role in the immune response to viruses.[78]

Unlike animals, plants lack phagocytic cells, but many plant immune responses involve systemic chemical signals that are sent through a plant.[79] Individual plant cells respond to molecules associated with pathogens known as Pathogen-associated molecular patterns or PAMPs.[80] When a part of a plant becomes infected, the plant produces a localized hypersensitive response, whereby cells at the site of infection undergo rapid apoptosis to prevent the spread of the disease to other parts of the plant. Systemic acquired resistance (SAR) is a type of defensive response used by plants that renders the entire plant resistant to a particular infectious agent.[79] RNA silencing mechanisms are particularly important in this systemic response as they can block virus replication.[81]

Tumor immunology

Another important role of the immune system is to identify and eliminate tumors. The transformed cells of tumors express antigens that are not found on normal cells. To the immune system, these antigens appear foreign, and their presence causes immune cells to attack the transformed tumor cells. The antigens expressed by tumors have several sources;[83] some are derived from oncogenic viruses like human papillomavirus, which causes cervical cancer,[84] while others are the organism's own proteins that occur at low levels in normal cells but reach high levels in tumor cells. One example is an enzyme called tyrosinase that, when expressed at high levels, transforms certain skin cells (e.g. melanocytes) into tumors called melanomas.[85][86] A third possible source of tumor antigens are proteins normally important for regulating cell growth and survival, that commonly mutate into cancer inducing molecules called oncogenes.[83][87][88]

The main response of the immune system to tumors is to destroy the abnormal cells using killer T cells, sometimes with the assistance of helper T cells.[86][89] Tumor antigens are presented on MHC class I molecules in a similar way to viral antigens. This allows killer T cells to recognize the tumor cell as abnormal.[90] NK cells also kill tumorous cells in a similar way, especially if the tumor cells have fewer MHC class I molecules on their surface than normal; this is a common phenomenon with tumors.[91] Sometimes antibodies are generated against tumor cells allowing for their destruction by the complement system.[87]

Clearly, some tumors evade the immune system and go on to become cancers.[92] Tumor cells often have a reduced number of MHC class I molecules on their surface, thus avoiding detection by killer T cells.[90] Some tumor cells also release products that inhibit the immune response; for example by secreting the cytokine TGF-β, which suppresses the activity of macrophages and lymphocytes.[93] In addition, immunological tolerance may develop against tumor antigens, so the immune system no longer attacks the tumor cells.[92]

Paradoxically, macrophages can promote tumor growth [94] when tumor cells send out cytokines that attract macrophages, which then generate cytokines and growth factors that nurture tumor development. In addition, a combination of hypoxia in the tumor and a cytokine produced by macrophages induces tumor cells to decrease production of a protein that blocks metastasis and thereby assists spread of cancer cells.

Physiological regulation

Hormones can act as immunomodulators, altering the sensitivity of the immune system. For example, female sex hormones are known immunostimulators of both adaptive[95] and innate immune responses.[96] Some autoimmune diseases such as lupus erythematosus strike women preferentially, and their onset often coincides with puberty. By contrast, male sex hormones such as testosterone seem to be immunosuppressive.[97] Other hormones appear to regulate the immune system as well, most notably prolactin, growth hormone and vitamin D.[98][99]

When a T-cell encounters a foreign pathogen, it extends a vitamin D receptor. This is essentially a signaling device that allows the T-cell to bind to the active form of vitamin D, the steroid hormone calcitriol. T-cells have a symbiotic relationship with vitamin D. Not only does the T-cell extend a vitamin D receptor, in essence asking to bind to the steroid hormone version of vitamin D, calcitriol, but the T-cell expresses the gene CYP27B1, which is the gene responsible for converting the pre-hormone version of vitamin D, calcidiol into the steroid hormone version, calcitriol. Only after binding to calcitriol can T-cells perform their intended function. Other immune system cells that are known to express CYP27B1 and thus activate vitamin D calcidiol, are dendritic cells, keratinocytes and macrophages.[100][101]

It is conjectured that a progressive decline in hormone levels with age is partially responsible for weakened immune responses in aging individuals.[102] Conversely, some hormones are regulated by the immune system, notably thyroid hormone activity.[103] The age-related decline in immune function is also related to dropping vitamin D levels in the elderly. As people age, two things happen that negatively affect their vitamin D levels. First, they stay indoors more due to decreased activity levels. This means that they get less sun and therefore produce less cholecalciferol via UVB radiation. Second, as a person ages the skin becomes less adept at producing vitamin D.[104]

The immune system is affected by sleep and rest,[105] and sleep deprivation is detrimental to immune function.[106] Complex feedback loops involving cytokines, such as interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α produced in response to infection, appear to also play a role in the regulation of non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.[107] Thus the immune response to infection may result in changes to the sleep cycle, including an increase in slow-wave sleep relative to REM sleep.[108]

Nutrition and diet

Overnutrition is associated with diseases such as diabetes and obesity, which are known to affect immune function. More moderate malnutrition, as well as certain specific trace mineral and nutrient deficiencies, can also compromise the immune response.[109][page needed]

Foods rich in certain fatty acids may foster a healthy immune system.[110] Likewise, fetal undernourishment can cause a lifelong impairment of the immune system.[111]

Manipulation in medicine

The immune response can be manipulated to suppress unwanted responses resulting from autoimmunity, allergy, and transplant rejection, and to stimulate protective responses against pathogens that largely elude the immune system (see immunization). Immunosuppressive drugs are used to control autoimmune disorders or inflammation when excessive tissue damage occurs, and to prevent transplant rejection after an organ transplant.[35][112]

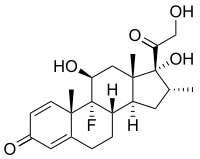

Anti-inflammatory drugs are often used to control the effects of inflammation. Glucocorticoids are the most powerful of these drugs; however, these drugs can have many undesirable side effects, such as central obesity, hyperglycemia, osteoporosis, and their use must be tightly controlled.[113] Lower doses of anti-inflammatory drugs are often used in conjunction with cytotoxic or immunosuppressive drugs such as methotrexate or azathioprine. Cytotoxic drugs inhibit the immune response by killing dividing cells such as activated T cells. However, the killing is indiscriminate and other constantly dividing cells and their organs are affected, which causes toxic side effects.[112] Immunosuppressive drugs such as ciclosporin prevent T cells from responding to signals correctly by inhibiting signal transduction pathways.[114]

Larger drugs (>500 Da) can provoke a neutralizing immune response, particularly if the drugs are administered repeatedly, or in larger doses. This limits the effectiveness of drugs based on larger peptides and proteins (which are typically larger than 6000 Da). In some cases, the drug itself is not immunogenic, but may be co-administered with an immunogenic compound, as is sometimes the case for Taxol. Computational methods have been developed to predict the immunogenicity of peptides and proteins, which are particularly useful in designing therapeutic antibodies, assessing likely virulence of mutations in viral coat particles, and validation of proposed peptide-based drug treatments. Early techniques relied mainly on the observation that hydrophilic amino acids are overrepresented in epitope regions than hydrophobic amino acids;[115] however, more recent developments rely on machine learning techniques using databases of existing known epitopes, usually on well-studied virus proteins, as a training set.[116] A publicly accessible database has been established for the cataloguing of epitopes from pathogens known to be recognizable by B cells.[117] The emerging field of bioinformatics-based studies of immunogenicity is referred to as immunoinformatics.[118] Immunoproteomics is the study of large sets of proteins (proteomics) involved in the immune response.

Manipulation by pathogens

The success of any pathogen depends on its ability to elude host immune responses. Therefore, pathogens evolved several methods that allow them to successfully infect a host, while evading detection or destruction by the immune system.[119] Bacteria often overcome physical barriers by secreting enzymes that digest the barrier, for example, by using a type II secretion system.[120] Alternatively, using a type III secretion system, they may insert a hollow tube into the host cell, providing a direct route for proteins to move from the pathogen to the host. These proteins are often used to shut down host defenses.[121]

An evasion strategy used by several pathogens to avoid the innate immune system is to hide within the cells of their host (also called intracellular pathogenesis). Here, a pathogen spends most of its life-cycle inside host cells, where it is shielded from direct contact with immune cells, antibodies and complement. Some examples of intracellular pathogens include viruses, the food poisoning bacterium Salmonella and the eukaryotic parasites that cause malaria (Plasmodium falciparum) and leishmaniasis (Leishmania spp.). Other bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, live inside a protective capsule that prevents lysis by complement.[122] Many pathogens secrete compounds that diminish or misdirect the host's immune response.[119] Some bacteria form biofilms to protect themselves from the cells and proteins of the immune system. Such biofilms are present in many successful infections, e.g., the chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cenocepacia infections characteristic of cystic fibrosis.[123] Other bacteria generate surface proteins that bind to antibodies, rendering them ineffective; examples include Streptococcus (protein G), Staphylococcus aureus (protein A), and Peptostreptococcus magnus (protein L).[124]

The mechanisms used to evade the adaptive immune system are more complicated. The simplest approach is to rapidly change non-essential epitopes (amino acids and/or sugars) on the surface of the pathogen, while keeping essential epitopes concealed. This is called antigenic variation. An example is HIV, which mutates rapidly, so the proteins on its viral envelope that are essential for entry into its host target cell are constantly changing. These frequent changes in antigens may explain the failures of vaccines directed at this virus.[125] The parasite Trypanosoma brucei uses a similar strategy, constantly switching one type of surface protein for another, allowing it to stay one step ahead of the antibody response.[126] Masking antigens with host molecules is another common strategy for avoiding detection by the immune system. In HIV, the envelope that covers the virion is formed from the outermost membrane of the host cell; such "self-cloaked" viruses make it difficult for the immune system to identify them as "non-self" structures.[127]

See also

- Clonal selection

- Hapten

- Human physiology

- Immune network theory

- Immune system receptors

- Immunoproteomics

- Immunostimulator

- Original antigenic sin

- Plant disease resistance

- Polyclonal response

- Tumor antigens

References

- ^ a b c Beck, Gregory (1996). "Immunity and the Invertebrates" (PDF). Scientific American. 275 (5): 60–66. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1196-60. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Inflammatory Cells and Cancer", Lisa M. Coussens and Zena Werb, Journal of Experimental Medicine, March 19, 2001, vol. 193, no. 6, pages F23-26, Retrieved Aug 13, 2010

- ^ "Chronic Immune Activation and Inflammation as the Cause of Malignancy", K.J. O'Byrne and A.G. Dalgleish, British Journal of Cancer, August 2001, vol. 85, no. 4, pages 473–483, Retrieved Aug 13, 2010

- ^ Retief FP, Cilliers L (1998). "The epidemic of Athens, 430–426 BC". South African Medical Journal. 88 (1): 50–3. PMID 9539938.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ostoya P (1954). "Maupertuis et la biologie". Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications. 7 (1): 60–78. doi:10.3406/rhs.1954.3379.

- ^ Plotkin SA (2005). "Vaccines: past, present and future". Nature Medicine. 11 (4 Suppl): S5–11. doi:10.1038/nm1209. PMID 15812490.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905 Nobelprize.org Accessed 8 January 2007.

- ^ Major Walter Reed, Medical Corps, U.S. Army Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Accessed 8 January 2007.

- ^

Metchnikoff, Elie (1905). Immunity in Infective Diseases (Full Text Version: Google Books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 68025143.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1908 Nobelprize.org Accessed 8 January 2007

- ^ a b Litman GW, Cannon JP, Dishaw LJ (2005). "Reconstructing immune phylogeny: new perspectives". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 5 (11): 866–79. doi:10.1038/nri1712. PMID 16261174.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mayer, Gene (2006). "Immunology — Chapter One: Innate (non-specific) Immunity". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Smith A.D. (Ed) Oxford dictionary of biochemistry and molecular biology. (1997) Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854768-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Alberts, Bruce (2002). Molecular Biology of the Cell; Fourth Edition. New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-3218-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Boyton RJ, Openshaw PJ (2002). "Pulmonary defences to acute respiratory infection". British Medical Bulletin. 61 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1093/bmb/61.1.1. PMID 11997295.

- ^ Agerberth B, Gudmundsson GH (2006). "Host antimicrobial defence peptides in human disease". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 306: 67–90. doi:10.1007/3-540-29916-5_3. ISBN 978-3-540-29915-8. PMID 16909918.

- ^ Moreau JM, Girgis DO, Hume EB, Dajcs JJ, Austin MS, O'Callaghan RJ (2001). "Phospholipase A(2) in rabbit tears: a host defense against Staphylococcus aureus". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 42 (10): 2347–54. PMID 11527949.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hankiewicz J, Swierczek E (1974). "Lysozyme in human body fluids". Clinica Chimica Acta. 57 (3): 205–9. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(74)90398-2. PMID 4434640.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Fair WR, Couch J, Wehner N (1976). "Prostatic antibacterial factor. Identity and significance". Urology. 7 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(76)90305-8. PMID 54972.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yenugu S, Hamil KG, Birse CE, Ruben SM, French FS, Hall SH (2003). "Antibacterial properties of the sperm-binding proteins and peptides of human epididymis 2 (HE2) family; salt sensitivity, structural dependence and their interaction with outer and cytoplasmic membranes of Escherichia coli". The Biochemical Journal. 372 (Pt 2): 473–83. doi:10.1042/BJ20030225. PMC 1223422. PMID 12628001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gorbach SL (1990). "Lactic acid bacteria and human health". Annals of Medicine. 22 (1): 37–41. doi:10.3109/07853899009147239. PMID 2109988.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hill LV, Embil JA (1986). "Vaginitis: current microbiologic and clinical concepts". CMAJ. 134 (4): 321–31. PMC 1490817. PMID 3510698.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reid G, Bruce AW (2003). "Urogenital infections in women: can probiotics help?". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 79 (934): 428–32. doi:10.1136/pmj.79.934.428. PMC 1742800. PMID 12954951.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Salminen SJ, Gueimonde M, Isolauri E (2005). "Probiotics that modify disease risk". The Journal of Nutrition. 135 (5): 1294–8. PMID 15867327.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Reid G, Jass J, Sebulsky MT, McCormick JK (2003). "Potential Uses of Probiotics in Clinical Practice". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (4): 658–72. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.4.658-672.2003. PMC 207122. PMID 14557292.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Medzhitov R (2007). "Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response". Nature. 449 (7164): 819–26. Bibcode:2007Natur.449..819M. doi:10.1038/nature06246. PMID 17943118.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Matzinger P (2002). "The danger model: a renewed sense of self". Science. 296 (5566): 301–5. Bibcode:2002Sci...296..301M. doi:10.1126/science.1071059. PMID 11951032.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kawai T, Akira S (2006). "Innate immune recognition of viral infection". Nature Immunology. 7 (2): 131–7. doi:10.1038/ni1303. PMID 16424890.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miller SB (2006). "Prostaglandins in health and disease: an overview". Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 36 (1): 37–49. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.03.005. PMID 16887467.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ogawa Y, Calhoun WJ (2006). "The role of leukotrienes in airway inflammation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 118 (4): 789–98, quiz 799–800. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.08.009. PMID 17030228.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Le Y, Zhou Y, Iribarren P, Wang J (2004). "Chemokines and chemokine receptors: their manifold roles in homeostasis and disease" (PDF). Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 1 (2): 95–104. PMID 16212895.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin P, Leibovich SJ (2005). "Inflammatory cells during wound repair: the good, the bad and the ugly". Trends in Cell Biology. 15 (11): 599–607. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2005.09.002. PMID 16202600.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rus H, Cudrici C, Niculescu F (2005). "The role of the complement system in innate immunity". Immunologic Research. 33 (2): 103–12. doi:10.1385/IR:33:2:103. PMID 16234578.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mayer, Gene (2006). "Immunology — Chapter Two: Complement". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Janeway CA, Jr.; et al. (2005). Immunobiology (6th ed.). Garland Science. ISBN 0-443-07310-4.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Liszewski MK, Farries TC, Lublin DM, Rooney IA, Atkinson JP (1996). "Control of the complement system". Advances in Immunology. Advances in Immunology. 61: 201–83. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60868-8. ISBN 978-0-12-022461-6. PMID 8834497.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sim RB, Tsiftsoglou SA (2004). "Proteases of the complement system" (PDF). Biochemical Society Transactions. 32 (Pt 1): 21–7. doi:10.1042/BST0320021. PMID 14748705.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ryter A (1985). "Relationship between ultrastructure and specific functions of macrophages". Comparative Immunology, Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 8 (2): 119–33. doi:10.1016/0147-9571(85)90039-6. PMID 3910340.

- ^ Langermans JA, Hazenbos WL, van Furth R (1994). "Antimicrobial functions of mononuclear phagocytes". Journal of Immunological Methods. 174 (1–2): 185–94. doi:10.1016/0022-1759(94)90021-3. PMID 8083520.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ May RC, Machesky LM (2001). "Phagocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton". Journal of Cell Science. 114 (Pt 6): 1061–77. PMID 11228151.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Salzet M, Tasiemski A, Cooper E (2006). "Innate immunity in lophotrochozoans: the annelids". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 12 (24): 3043–50. doi:10.2174/138161206777947551. PMID 16918433.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zen K, Parkos CA (2003). "Leukocyte-epithelial interactions". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 15 (5): 557–64. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00103-0. PMID 14519390.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Stvrtinová, Viera (1995). Inflammation and Fever from Pathophysiology: Principles of Disease. Computing Centre, Slovak Academy of Sciences: Academic Electronic Press. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bowers, William (2006). "Immunology -Chapter Thirteen: Immunoregulation". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ a b Guermonprez P, Valladeau J, Zitvogel L, Théry C, Amigorena S (2002). "Antigen presentation and T cell stimulation by dendritic cells". Annual Review of Immunology. 20 (1): 621–67. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064828. PMID 11861614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krishnaswamy G, Ajitawi O, Chi DS (2006). "The human mast cell: an overview". Methods in Molecular Biology. 315: 13–34. PMID 16110146.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kariyawasam HH, Robinson DS (2006). "The eosinophil: the cell and its weapons, the cytokines, its locations". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 27 (2): 117–27. doi:10.1055/s-2006-939514. PMID 16612762.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Middleton D, Curran M, Maxwell L (2002). "Natural killer cells and their receptors". Transplant Immunology. 10 (2–3): 147–64. doi:10.1016/S0966-3274(02)00062-X. PMID 12216946.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pancer Z, Cooper MD (2006). "The evolution of adaptive immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 24 (1): 497–518. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090542. PMID 16551257.

- ^ a b Holtmeier W, Kabelitz D (2005). "gammadelta T cells link innate and adaptive immune responses". Chemical Immunology and Allergy. Chemical Immunology and Allergy. 86: 151–83. doi:10.1159/000086659. ISBN 3-8055-7862-8. PMID 15976493.

- ^ Harty JT, Tvinnereim AR, White DW (2000). "CD8+ T cell effector mechanisms in resistance to infection". Annual Review of Immunology. 18 (1): 275–308. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.275. PMID 10837060.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Radoja S, Frey AB, Vukmanovic S (2006). "T-cell receptor signaling events triggering granule exocytosis". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 26 (3): 265–90. PMID 16928189.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A (1996). "Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes". Nature. 383 (6603): 787–93. Bibcode:1996Natur.383..787A. doi:10.1038/383787a0. PMID 8893001.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McHeyzer-Williams LJ, Malherbe LP, McHeyzer-Williams MG (2006). "Helper T cell-regulated B cell immunity". Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. 311: 59–83. doi:10.1007/3-540-32636-7_3. ISBN 978-3-540-32635-9. PMID 17048705.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kovacs B, Maus MV, Riley JL; et al. (2002). "Human CD8+ T cells do not require the polarization of lipid rafts for activation and proliferation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (23): 15006–11. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9915006K. doi:10.1073/pnas.232058599. PMC 137535. PMID 12419850.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Grewal IS, Flavell RA (1998). "CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity". Annual Review of Immunology. 16 (1): 111–35. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. PMID 9597126.

- ^ Girardi M (2006). "Immunosurveillance and immunoregulation by gammadelta T cells". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 126 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700003. PMID 16417214.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Understanding the Immune System: How it Works" (PDF). National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ a b Sproul TW, Cheng PC, Dykstra ML, Pierce SK (2000). "A role for MHC class II antigen processing in B cell development". International Reviews of Immunology. 19 (2–3): 139–55. doi:10.3109/08830180009088502. PMID 10763706.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kehry MR, Hodgkin PD (1994). "B-cell activation by helper T-cell membranes". Critical Reviews in Immunology. 14 (3–4): 221–38. PMID 7538767.

- ^ Bowers, William (2006). "Immunology — Chapter nine: Cells involved in immune responses". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ Alder MN, Rogozin IB, Iyer LM, Glazko GV, Cooper MD, Pancer Z (2005). "Diversity and function of adaptive immune receptors in a jawless vertebrate". Science. 310 (5756): 1970–3. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1970A. doi:10.1126/science.1119420. PMID 16373579.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Saji F, Samejima Y, Kamiura S, Koyama M (1999). "Dynamics of immunoglobulins at the feto-maternal interface". Reviews of Reproduction. 4 (2): 81–9. doi:10.1530/ror.0.0040081. PMID 10357095.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Van de Perre P (2003). "Transfer of antibody via mother's milk". Vaccine. 21 (24): 3374–6. doi:10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00336-0. PMID 12850343.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Keller MA, Stiehm ER (2000). "Passive Immunity in Prevention and Treatment of Infectious Diseases". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 13 (4): 602–14. doi:10.1128/CMR.13.4.602-614.2000. PMC 88952. PMID 11023960.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Death and DALY estimates for 2002 by cause for WHO Member States. World Health Organization. Retrieved on 1 January 2007.

- ^ Singh M, O'Hagan D (1999). "Advances in vaccine adjuvants". Nature Biotechnology. 17 (11): 1075–81. doi:10.1038/15058. PMID 10545912.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Aw D, Silva AB, Palmer DB (2007). "Immunosenescence: emerging challenges for an ageing population". Immunology. 120 (4): 435–46. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02555.x. PMC 2265901. PMID 17313487.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Chandra RK (1997). "Nutrition and the immune system: an introduction". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 66 (2): 460S–463S. PMID 9250133.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miller JF (2002). "The discovery of thymus function and of thymus-derived lymphocytes". Immunological Reviews. 185 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1034/j.1600-065X.2002.18502.x. PMID 12190917.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Joos L, Tamm M (2005). "Breakdown of pulmonary host defense in the immunocompromised host: cancer chemotherapy". Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2 (5): 445–8. doi:10.1513/pats.200508-097JS. PMID 16322598.

- ^ Copeland KF, Heeney JL (1996). "T helper cell activation and human retroviral pathogenesis". Microbiological Reviews. 60 (4): 722–42. PMC 239461. PMID 8987361.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miller JF (1993). "Self-nonself discrimination and tolerance in T and B lymphocytes". Immunologic Research. 12 (2): 115–30. doi:10.1007/BF02918299. PMID 8254222.

- ^ a b c d Ghaffar, Abdul (2006). "Immunology — Chapter Seventeen: Hypersensitivity Reactions". Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook. USC School of Medicine. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ Bickle TA, Krüger DH (1993). "Biology of DNA restriction". Microbiological Reviews. 57 (2): 434–50. PMC 372918. PMID 8336674.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barrangou R, Fremaux C, Deveau H; et al. (2007). "CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes". Science. 315 (5819): 1709–12. Bibcode:2007Sci...315.1709B. doi:10.1126/science.1138140. PMID 17379808.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brouns SJ, Jore MM, Lundgren M; et al. (2008). "Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes". Science. 321 (5891): 960–4. Bibcode:2008Sci...321..960B. doi:10.1126/science.1159689. PMID 18703739.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stram Y, Kuzntzova L (2006). "Inhibition of viruses by RNA interference". Virus Genes. 32 (3): 299–306. doi:10.1007/s11262-005-6914-0. PMID 16732482.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Schneider, David (Spring 2005). "Innate Immunity — Lecture 4: Plant immune responses". Stanford University Department of Microbiology and Immunology. Retrieved 1 January 2007. [dead link]

- ^ Jones DG, Dangl JL (2006). "The plant immune system". Nature. 444 (7117): 323–9. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..323J. doi:10.1038/nature05286. PMID 17108957.

- ^ Baulcombe D (2004). "RNA silencing in plants". Nature. 431 (7006): 356–63. Bibcode:2004Natur.431..356B. doi:10.1038/nature02874. PMID 15372043.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Morgan RA, Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR; et al. (2006). "Cancer Regression in Patients After Transfer of Genetically Engineered Lymphocytes". Science. 314 (5796): 126–9. Bibcode:2006Sci...314..126M. doi:10.1126/science.1129003. PMC 2267026. PMID 16946036.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Andersen MH, Schrama D, Thor Straten P, Becker JC (2006). "Cytotoxic T cells". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 126 (1): 32–41. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700001. PMID 16417215.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boon T, van der Bruggen P (1996). "Human tumor antigens recognized by T lymphocytes". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 183 (3): 725–9. doi:10.1084/jem.183.3.725. PMC 2192342. PMID 8642276.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Castelli C, Rivoltini L, Andreola G, Carrabba M, Renkvist N, Parmiani G (2000). "T-cell recognition of melanoma-associated antigens". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 182 (3): 323–31. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<323::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-#. PMID 10653598.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Romero P, Cerottini JC, Speiser DE (2006). "The human T cell response to melanoma antigens". Advances in Immunology. Advances in Immunology. 92: 187–224. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(06)92005-7. ISBN 978-0-12-373636-9. PMID 17145305.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Guevara-Patiño JA, Turk MJ, Wolchok JD, Houghton AN (2003). "Immunity to cancer through immune recognition of altered self: studies with melanoma". Advances in Cancer Research. Advances in Cancer Research. 90: 157–77. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(03)90005-4. ISBN 978-0-12-006690-2. PMID 14710950.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Renkvist N, Castelli C, Robbins PF, Parmiani G (2001). "A listing of human tumor antigens recognized by T cells". Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 50 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1007/s002620000169. PMID 11315507.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gerloni M, Zanetti M (2005). "CD4 T cells in tumor immunity". Springer Seminars in Immunopathology. 27 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1007/s00281-004-0193-z. PMID 15965712.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Seliger B, Ritz U, Ferrone S (2006). "Molecular mechanisms of HLA class I antigen abnormalities following viral infection and transformation". International Journal of Cancer. 118 (1): 129–38. doi:10.1002/ijc.21312. PMID 16003759.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hayakawa Y, Smyth MJ (2006). "Innate immune recognition and suppression of tumors". Advances in Cancer Research. 95: 293–322. doi:10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95008-8. PMID 16860661.

- ^ a b Seliger B (2005). "Strategies of tumor immune evasion". BioDrugs. 19 (6): 347–54. doi:10.2165/00063030-200519060-00002. PMID 16392887.

- ^ Frumento G, Piazza T, Di Carlo E, Ferrini S (2006). "Targeting tumor-related immunosuppression for cancer immunotherapy". Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 6 (3): 233–7. doi:10.2174/187153006778250019. PMID 17017974.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stix, Gary (2007). "A Malignant Flame" (PDF). Scientific American. 297 (1): 60–67. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0707-60. PMID 17695843. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Wira, CR (2004). "Endocrine regulation of the mucosal immune system in the female reproductive tract". In In: Ogra PL, Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, McGhee JR, Bienenstock J (eds.) (ed.). Mucosal Immunology. San Francisco: Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-491543-4.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Lang TJ (2004). "Estrogen as an immunomodulator". Clinical Immunology. 113 (3): 224–30. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2004.05.011. PMID 15507385.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Moriyama A, Shimoya K, Ogata I; et al. (1999). "Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) concentrations in cervical mucus of women with normal menstrual cycle". Molecular Human Reproduction. 5 (7): 656–61. doi:10.1093/molehr/5.7.656. PMID 10381821.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Cutolo M, Sulli A, Capellino S; et al. (2004). "Sex hormones influence on the immune system: basic and clinical aspects in autoimmunity". Lupus. 13 (9): 635–8. doi:10.1191/0961203304lu1094oa. PMID 15485092.{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

King AE, Critchley HO, Kelly RW (2000). "Presence of secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor in human endometrium and first trimester decidua suggests an antibacterial protective role". Molecular Human Reproduction. 6 (2): 191–6. doi:10.1093/molehr/6.2.191. PMID 10655462.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fimmel S, Zouboulis CC (2005). "Influence of physiological androgen levels on wound healing and immune status in men". The Aging Male. 8 (3–4): 166–74. doi:10.1080/13685530500233847. PMID 16390741.

- ^ Dorshkind K, Horseman ND (2000). "The roles of prolactin, growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-I, and thyroid hormones in lymphocyte development and function: insights from genetic models of hormone and hormone receptor deficiency". Endocrine Reviews. 21 (3): 292–312. doi:10.1210/er.21.3.292. PMID 10857555.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Nagpal S, Na S, Rathnachalam R (2005). "Noncalcemic actions of vitamin D receptor ligands". Endocrine Reviews. 26 (5): 662–87. doi:10.1210/er.2004-0002. PMID 15798098.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Marina Rode von Essen, Martin Kongsbak, Peter Schjerling, Klaus Olgaard, Niels Ødum & Carsten Geisler (2010). "Vitamin D controls T cell antigen receptor signaling and activation of human T cells". Nature Immunology. 11 (4): 344–349. doi:10.1038/ni.1851. PMID 20208539.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sigmundsdottir H, Pan J, Debes GF; et al. (2007). "DCs metabolize sunlight-induced vitamin D3 to 'program' T cell attraction to the epidermal chemokine CCL27". Nat. Immunol. 8 (3): 285–93. doi:10.1038/ni1433. PMID 17259988.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hertoghe T (2005). "The 'multiple hormone deficiency' theory of aging: is human senescence caused mainly by multiple hormone deficiencies?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1057 (1): 448–65. Bibcode:2005NYASA1057..448H. doi:10.1196/annals.1322.035. PMID 16399912.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Klein JR (2006). "The Immune System as a Regulator of Thyroid Hormone Activity". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 231 (3): 229–36. PMC 2768616. PMID 16514168.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Leif Mosekilde (2005). "Vitamin D and the elderly". Clinical Endocrinology. 62 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02226.x. PMID 15730407.

- ^ Lange T, Perras B, Fehm HL, Born J (2003). "Sleep enhances the human antibody response to hepatitis A vaccination". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (5): 831–5. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000091382.61178.F1. PMID 14508028.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bryant PA, Trinder J, Curtis N (2004). "Sick and tired: Does sleep have a vital role in the immune system?". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 4 (6): 457–67. doi:10.1038/nri1369. PMID 15173834.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Krueger JM, Majde JA (2003). "Humoral links between sleep and the immune system: research issues". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 992 (1): 9–20. Bibcode:2003NYASA.992....9K. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03133.x. PMID 12794042.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Majde JA, Krueger JM (2005). "Links between the innate immune system and sleep". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 116 (6): 1188–98. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.005. PMID 16337444.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ R.M. Suskind, C.L. Lachney, J.N. Udall, Jr., "Malnutrition and the Immune Response", in: Dairy products in human health and nutrition, M. Serrano-Ríos, ed., CRC Press, 1994.

- ^ Pond CM (2005). "Adipose tissue and the immune system". Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes, and Essential Fatty Acids. 73 (1): 17–30. doi:10.1016/j.plefa.2005.04.005. PMID 15946832.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Langley-Evans SC, Carrington LJ (2006). "Diet and the developing immune system". Lupus. 15 (11): 746–52. doi:10.1177/0961203306070001. PMID 17153845.

- ^ a b Taylor AL, Watson CJ, Bradley JA (2005). "Immunosuppressive agents in solid organ transplantation: Mechanisms of action and therapeutic efficacy". Critical Reviews in Oncology/hematology. 56 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.03.012. PMID 16039869.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barnes PJ (2006). "Corticosteroids: the drugs to beat". European Journal of Pharmacology. 533 (1–3): 2–14. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.052. PMID 16436275.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Masri MA (2003). "The mosaic of immunosuppressive drugs". Molecular Immunology. 39 (17–18): 1073–7. doi:10.1016/S0161-5890(03)00075-0. PMID 12835079.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Welling GW, Weijer WJ, van der Zee R, Welling-Wester S (1985). "Prediction of sequential antigenic regions in proteins". FEBS Letters. 188 (2): 215–8. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(85)80374-4. PMID 2411595.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Söllner J, Mayer B (2006). "Machine learning approaches for prediction of linear B-cell epitopes on proteins". Journal of Molecular Recognition. 19 (3): 200–8. doi:10.1002/jmr.771. PMID 16598694.

- ^ Saha S, Bhasin M, Raghava GP (2005). "Bcipep: A database of B-cell epitopes". BMC Genomics. 6 (1): 79. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-6-79. PMC 1173103. PMID 15921533.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Flower DR, Doytchinova IA (2002). "Immunoinformatics and the prediction of immunogenicity". Applied Bioinformatics. 1 (4): 167–76. PMID 15130835.

- ^ a b Finlay BB, McFadden G (2006). "Anti-immunology: evasion of the host immune system by bacterial and viral pathogens". Cell. 124 (4): 767–82. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.034. PMID 16497587.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cianciotto NP (2005). "Type II secretion: a protein secretion system for all seasons". Trends in Microbiology. 13 (12): 581–8. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.09.005. PMID 16216510.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Winstanley C, Hart CA (2001). "Type III secretion systems and pathogenicity islands". J. Med. Microbiol. 50 (2): 116–26. PMID 11211218.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Finlay BB, Falkow S (1997). "Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited". Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61 (2): 136–69. PMC 232605. PMID 9184008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kobayashi H (2005). "Airway biofilms: implications for pathogenesis and therapy of respiratory tract infections". Treatments in Respiratory Medicine. 4 (4): 241–53. doi:10.2165/00151829-200504040-00003. PMID 16086598.

- ^ Housden NG, Harrison S, Roberts SE; et al. (2003). "Immunoglobulin-binding domains: Protein L from Peptostreptococcus magnus". Biochemical Society Transactions. 31 (Pt 3): 716–8. doi:10.1042/BST0310716. PMID 12773190.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burton DR, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA (2005). "Antibody vs. HIV in a clash of evolutionary titans". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (42): 14943–8. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10214943B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505126102. PMC 1257708. PMID 16219699.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Taylor JE, Rudenko G (2006). "Switching trypanosome coats: what's in the wardrobe?". Trends in Genetics. 22 (11): 614–20. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.08.003. PMID 16908087.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Cantin R, Méthot S, Tremblay MJ (2005). "Plunder and Stowaways: Incorporation of Cellular Proteins by Enveloped Viruses". Journal of Virology. 79 (11): 6577–87. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.11.6577-6587.2005. PMC 1112128. PMID 15890896.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- Immune System – from the University of Hartford (high school/undergraduate level)

- Microbiology and Immunology On-Line Textbook – from the University of South Carolina School of Medicine (undergraduate level)

- Immunobiology; Fifth Edition – Online version of the textbook by Charles Janeway (Advanced undergraduate/graduate level)

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA