Nord Stream 1

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (March 2022) |

| Nord Stream 1 | |

|---|---|

Location of Nord Stream 1 | |

| Location | |

| Country |

|

| Coordinates | |

| General direction | east–west–south |

| From | Vyborg, Russian Federation |

| Passes through | Gulf of Finland and Baltic Sea |

| To | Lubmin near Greifswald, Germany |

| General information | |

| Type | Natural gas |

| Partners | |

| Operator | Nord Stream AG |

| Manufacturer of pipes | |

| Installer of pipes | Saipem |

| Pipe layer | Castoro Sei |

| Contractors |

|

| Commissioned |

|

| Technical information | |

| Length | 1,222 km (759 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 55 billion m3/a (1.9 trillion cu ft/a) |

| Diameter | 1,220 mm (48 in) |

| No. of compressor stations | 1 |

| Compressor stations | Portovaya |

| Website | www |

| Nord Stream 2 | |

|---|---|

Map of Nord Stream 2 | |

| Location | |

| Country |

|

| Coordinates | |

| General direction | east–west–south |

| From | Ust-Luga, Russia |

| Passes through | Gulf of Finland and Baltic Sea |

| To | Lubmin near Greifswald, Germany |

| General information | |

| Type | Natural gas |

| Partners | |

| Operator | Nord Stream 2 AG |

| Manufacturer of pipes |

|

| Installer of pipes | Allseas (Until 21 December 2019) |

| Pipe layer | |

| Expected | unknown[1] |

| Technical information | |

| Length | 1,230 km (760 mi) |

| Maximum discharge | 55 billion m3/a (1.9 trillion cu ft/a) |

| Diameter | 1,220 mm (48 in) |

| No. of compressor stations | 1 |

| Compressor stations | Slavyanskaya |

| Website | www.nord-stream2.com |

Nord Stream (German-English mixed expression; English North Stream; Template:Lang-ru, Severny potok) is the name for a pair of offshore natural gas pipelines in Europe that runs under the Baltic Sea from Russia to Germany. It comprises the Nord Stream 1 (NS1) pipeline running from Vyborg in northwestern Russia, near Finland, and the Nord Stream 2 (NS2) pipeline running from Ust-Luga in northwestern Russia near Estonia. Both pipelines run to Lubmin in the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern. Each pipeline comprises two lines of approximately 1,200 kilometres (750 mi) long. Nord Stream 2 has been denied certification due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine. The name "Nord Stream" occasionally refers to a wider pipeline network, including the feeding onshore pipeline in Russia, and further connections in Western Europe.[2]

In Lubmin, Nord Stream connects to the OPAL pipeline to Olbernhau in eastern Germany, on the Czech border, and to the NEL pipeline to Rehden near Bremen in north-western Germany.

Nord Stream 1 is owned and operated by Nord Stream AG, whose majority shareholder is the Russian state company Gazprom. Nord Stream 2 is owned and planned to be operated by Nord Stream 2 AG, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gazprom.

The first line of Nord Stream 1 was laid by May 2011 and was inaugurated on 8 November 2011.[3][4] The second line of Nord Stream 1 was laid in 2011–2012 and was inaugurated on 8 October 2012. At 1,222 km (759 mi) in length, Nord Stream 1 was the longest sub-sea pipeline in the world, surpassing the Norway-UK Langeled pipeline,[5][6] until surpassed by the 1,234-kilometre-long (767 mi) Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

The laying of Nord Stream 2 was carried out in 2018–2021.[7] The first line of Nord Stream 2 was completed in June 2021, and the second line was completed in September 2021.

Nord Stream 1 gave Nord Stream a total annual capacity of 55 billion m3 (1.9 trillion cu ft) of gas, and the construction of Nord Stream 2 would double this.[8][9][10]

The Nord Stream projects have been fiercely opposed by Central and Eastern European countries as well as the United States due to concerns that the pipelines would increase Russia's influence in Europe, and the knock-on reduction of transit fees for use of the existing pipelines in Central and Eastern European countries.

Germany suspended certification of Nord Stream 2 on 22 February 2022 in response to Russia's recognition of the Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics during the prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[11][12] As a result, Nord Stream 2 AG went into bankruptcy.[13]

On 26 September 2022, the NS1 and the NS2 pipelines experienced multiple unexplained large pressure drops to almost zero in international waters (two explosions at 1:03 and 18:04 MSK[14]), with Baltic Pipe opening mere hours later. Seismographic instruments revealed explosions and a visual inspection revealed leaks, which may be the result of sabotage.[15] Terje Aasland, Norway's Minister for Petroleum and Energy, said that the leaks were: "acts of sabotage." Both the Swedish and Danish Prime Ministers have called it "deliberate".[16]

History

Nord Stream 1, 1997–present

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: WP:PROSELINE. (September 2022) |

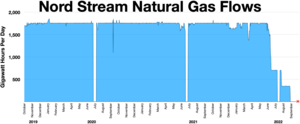

* Russia cut the flow of natural gas by more than half in June because they alleged they could not get a part seized by the Canadian government because of sanctions. Siemens, the producer of the part, denied that this piece was critical for operations.[18]

* Russia halted gas flows July 11th for annual maintenance for 10 days and resumed partial operations in July 21st[19]

* Russia stopped the flow of natural gas on 31 August 2022 for alleged maintenance for 3 days, but later said they could not provide a timeframe for restarting gas flow. The EU accused Russia of fabricating a false story to justify the cut.[20]

X Pipeline was Sabotaged 27 September 2022[21]

The pipeline project began in 1997 when Gazprom and Finnish oil company Neste (which merged in 1998 with Imatran Voima to form Fortum and in 2004 separated again into Fortum and Neste) formed the joint company North Transgas Oy for the construction and operation of a gas pipeline from Russia to Northern Germany across the Baltic Sea.[22] North Transgas cooperated with the German gas company Ruhrgas (which later became part of E.ON, which was later split into E.ON and Uniper). A route survey was done in the exclusive economic zones of Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany, and a feasibility study of the pipeline was conducted in 1998. Several routes were considered, including those with onshore segments through Finland and Sweden.[23]

On 24 April 2001, Gazprom, Fortum, Ruhrgas and Wintershall adopted a statement regarding a joint feasibility study for the construction of the pipeline.[24] On 18 November 2002, the Management Committee of Gazprom approved a schedule of project implementation. In May 2005, Fortum withdrew from the project and sold its stake in North Transgas to Gazprom. As a result, Gazprom became the only shareholder of North Transgas Oy.[22][25]

On 8 September 2005, Gazprom, BASF and E.ON signed a basic agreement on the construction of a North European Gas Pipeline. On 30 November 2005, the North European Gas Pipeline Company (later renamed Nord Stream AG, "Nord" is German for "North") was incorporated in Zug, Switzerland. On 9 December 2005, Gazprom started construction of the Russian onshore feeding pipeline (Gryazovets–Vyborg gas pipeline) in the town of Babayevo in Vologda Oblast.[26] The feeding pipeline was completed in 2010.

On 4 October 2006, the pipeline and the operating company were officially renamed Nord Stream AG.[27] After the establishment of Nord Stream AG, all information related to the pipeline project, including results of the seabed survey of 1998, was transferred from North Transgas to the new company, and on 2 November 2006, North Transgas was officially dissolved.[28]

The environmental impact assessment started on 16 November 2006 when notifications were sent to Russia, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Germany, as parties of origin (the countries whose exclusive economic zones and/or territorial waters the pipeline is planned to pass through), and Poland, Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia as affected parties.[29] The final report on transboundary environmental impact assessment was delivered on 9 March 2009.[30]

The gas systems operated by Finland's Gasum are connected to Nord Stream via a branch pipeline in Karelia.[31][32]

On 19 March 2007, Nord Stream AG hired Italian company Snamprogetti, a subsidiary of Saipem, for detailed design engineering of the pipeline.[33] A letter of intent for construction works was signed with Saipem on 17 September 2007 and the contract was concluded on 24 June 2008.[34][35] On 25 September 2007, the pipe supply contracts were awarded to the pipe producers EUROPIPE and OMK, and on 18 February 2008, the concrete weight coating and logistics services agreement was awarded to EUPEC PipeCoatings S.A.[36][37] The supply contracts for the second line were awarded to OMK, Europipe and Sumitomo Heavy Industries on 22 January 2010.[38] On 30 December 2008 Rolls-Royce Holdings was awarded a contract to supply turbines for the compressor, and on 8 January 2009, Royal Boskalis Westminster and Danish Dredging Contractor Rohde Nielsen A/S. were awarded a joint venture seabed dredging contract.[39][40]

The agreement to take Gasunie to the consortium as the fourth partner, was signed on 6 November 2007.[41] On 10 June 2008, Gasunie was included in the register of shareholders.[42] On 1 March 2010, French energy company GDF Suez signed with Gazprom a memorandum of understanding to acquire 9% stake in the project.[43] The transaction was closed in July 2010.[44]

In August 2008, Nord Stream AG hired former Finnish prime minister Paavo Lipponen as a consultant to help speed up the application process in Finland and to serve as a link between Nord Stream and Finnish authorities.[45]

On 21 December 2007, Nord Stream AG submitted application documents to the Swedish government for the pipeline construction in the Swedish Exclusive Economic Zone.[46] On 12 February 2008, the Swedish government rejected the consortium's application, which it had found incomplete.[47][48] A new application was filed later. On 20 October 2009, Nord Stream received a construction permit to build the pipeline in the Danish waters.[49] On 5 November 2009, the Swedish and Finnish authorities gave a permit to lay the pipeline in their exclusive economic zones.[50] On 22 February 2010, the Regional State Administrative Agency for Southern Finland issued the final environmental permit allowing construction of the Finnish section of the pipeline.[51][52]

On 15 January 2010 construction of the Portovaya compressor station in Vyborg, near the Gulf of Finland, began. [53] [54] The first pipe of the pipeline was laid on 6 April 2010 in the Swedish exclusive economic zone by the Castoro Sei vessel. In addition to Castoro Sei, also Castoro 10 and Solitaire were contracted for pipe-laying works.[55] Construction of the pipeline was officially launched on 9 April 2010 at Portovaya Bay.[56]

The laying of the first line was completed on 4 May 2011 (the last pipe put in place), while all underwater works on the first line were completed on 21 June 2011.[6] In August 2011, Nord Stream was connected with the OPAL pipeline.[57] The first gas was pumped into the first line on 6 September 2011.[58]

The pipeline was officially inaugurated by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev, French Prime Minister François Fillon, and Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte on 8 November 2011 at the ceremony held in Lubmin.[3][4][59] Construction of the second line was completed in August 2012 and it was inaugurated on 8 October 2012.[60]

In November 2015, Nord Stream found a disabled underwater drone with a small amount of explosives on the pipeline near Öland, and requested the Swedish Navy to remove it.[61][62]

Although the nominal capacity of the pipeline is 55 billion cubic metres (1.9 trillion cubic feet) per year, it transported 59.2 billion cubic metres (2.09 trillion cubic feet) in 2021.[63]

On 25 July 2022, Gazprom announced it will reduce gas flows to Germany to 20% of the maximum capacity, or 50% of the current throughput. The company shut down the pipeline for 10 days because of maintenance and claims the current reduction is due to a repair on a turbine in Montréal, Canada, that could not be delivered because of sanctions against Russia. The German government denied this claim and believed there was no reason for reducing the flow. Putin meanwhile during a press conference in Tehran said that these flows could be increased again if Russia receives more turbines from the manufacturer.[64]

On 31 August 2022, Gazprom halted any gas delivery through North Stream 1 for three days, officially because of maintenance.[65] On 2 September 2022, the company announced that natural gas supplies via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline would remain shut off indefinitely until the main gas turbine at the Portovaya compressor station near St Petersburg was fixed from an engine oil leak.[66] Gazprom justified this claiming that European Union sanctions against Russia have resulted in technical problems preventing it being able to provide the full volume of contracted gas through the pipeline; Siemens Energy, which maintains the turbine, rejected this and stated that there are no legal obstacles to its provision of maintenance for the pipeline.[66]

Nord Stream 2, 2011–2022

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: WP:PROSELINE. (September 2022) |

In 2011, Nord Stream AG started evaluation of an expansion project consisting of two additional lines (later named Nord Stream 2) to double the annual capacity up to 110 billion m3 (3.9 trillion cu ft). In August 2012, Nord Stream AG applied to the Finnish and Estonian governments for route studies in their underwater exclusive economic zones for the third and fourth lines.[67] A plan to route an additional pipeline to the United Kingdom was considered but abandoned.[68][69]

In January 2015, Gazprom announced that the expansion project had been put on hold since the existing lines were running at only half capacity due to EU sanctions on Russia[70] following its annexation of Crimea.

In June 2015, an agreement to build Nord Stream 2 was signed between Gazprom, Royal Dutch Shell, E.ON, OMV, and Engie.[71] As the creation of a joint venture was blocked by Poland,[clarification needed] on 24 April 2017, Uniper, Wintershall, Engie, OMV and Royal Dutch Shell signed a financing agreement with Nord Stream 2 AG, a subsidiary of Gazprom responsible for the development of the Nord Stream 2 project.[72]

On 31 January 2018, Germany granted Nord Stream 2 a permit for construction and operation in German waters and for landfall areas near Lubmin.[73]

In May 2018 construction started at the Greifswald end point.[74]

In January 2019, the US ambassador in Germany, Richard Grenell, sent letters to companies involved in the construction of Nord Stream 2 urging them to stop working on the project and threatening them with the possibility of sanctions.[75] In December 2019, the Republican Senators Ted Cruz and Ron Johnson also urged Allseas owner Edward Heerema to suspend the works on the pipeline, warning him that the United States would otherwise impose sanctions.[76] Cruz formally proposed such a bill to enable sanctions on 8 November 2021.[77]

On 21 December 2019, Allseas announced that the company had suspended its Nord Stream 2 pipelaying activities, anticipating enactment of the US National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, which contained sanctions.[78][79]

In May 2020, the German energy regulator refused an exception from competition rules that require Nord Stream 2 to separate gas ownership from transmission.[80] In August 2020, Poland fined Gazprom €50 million due to its lack of cooperation with an investigation launched by UOKiK, the Polish anti-monopoly watchdog. UOKiK cited competition rules against Gazprom and companies financing the project, suspecting that they had continued work on the pipeline without permission from the government of Poland.[81]

In December 2020, the Russian pipelaying ship Akademik Cherskiy continued pipe-laying.[82] In January, Fortuna, another pipe-layer, joined forces with the Akademik Cherskiy to complete the pipeline.[83] On 4 June 2021, Vladimir Putin announced that the pipe-laying for first line of the Nord Stream 2 had been fully completed. On 10 June, the sections of the pipeline were connected.[84] The laying of the second line was completed in September 2021.[85]

In June 2021, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that Nord Stream 2 completion was inevitable. In July 2021, the US urged Ukraine not to criticise a forthcoming agreement with Germany over the pipeline.[86][87] On July 20, Joe Biden and Angela Merkel reached a conclusive deal that the US may trigger sanctions if Russia used Nord Stream as a "political weapon". The deal aims to prevent Poland and Ukraine from being cut off from Russian gas supplies. Ukraine will receive a $50 million loan for green technology until 2024 and Germany will set up a billion-dollar fund to promote Ukraine's transition to green energy to compensate for the loss of the gas transit fees. The contract for transiting Russian gas through Ukraine will be prolonged until 2034 if the Russian government agrees.[88][89][90]

On November 16, 2021, European natural gas prices rose by 17% after Germany's energy regulator suspended approval of the Nord Stream 2.[91][92]

On December 9, 2021, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki called on Germany's newly appointed Chancellor Olaf Scholz to oppose the start-up of Nord Stream 2 and not to give in to pressure from Russia. On a visit to Rome, Morawiecki said: "I will call on Chancellor Scholz not to give in to pressure from Russia and not to allow Nord Stream 2 to be used as an instrument for blackmail against Ukraine, an instrument for blackmail against Poland, an instrument for blackmail against the European Union."[93]

Scholz suspended certification of Nord Stream 2 on 22 February 2022 in consequence of Russia's recognition of the Donetsk and Luhansk republics and the deployment of troops in territory held by the DPR and LPR.[94]

Nord Stream 2 AG filed for bankruptcy on 1 March 2022 and laid off all 106 employees from its headquarters in Zug, Switzerland.[95]

2022 gas leaks

On 26 September 2022, the NS1 and the NS2 pipelines both ruptured. Unexplained large pressure drops were reported in both pipelines at the end-station in Germany. A gas leak from NS2 was located late on 26 September. Early on 27 September, two separate leaks in NS1 were discovered. The leaks are in international waters, but within the Danish and Swedish economic zones.[96] Both Berliner Zeitung and Le Monde newspapers have asked if it is sabotage, and a Kremlin spokesman said it could be. Neither pipeline was in operation at the time of these incidents, but do contain gas.[97][98]

The sabotage of the Nord Stream pipelines happened as the Baltic Pipe was being opened for natural gas to come in from the North Sea through Denmark to Poland.[99][100][101]

Technical features

Russian onshore-pipeline

Nord Stream is fed by the Gryazovets–Vyborg gas pipeline. It is a part of the integrated gas transport network of Russia that connects the existing grid in Gryazovets with the coastal compressor station at Vyborg.[102] The length of the pipeline is 917 km (570 mi), the diameter of the pipe is 1,420 mm (56 in), and its working pressure is 100 atm (10 MPa), which is secured by six compressor stations. The Gryazovets-Vyborg pipeline, parallel to the branch of the Northern Lights pipeline (Gryazovets–Leningrad and Leningrad–Vyborg–Russian-state-border pipelines), also supplies gas to the Northwestern region of Russia (which includes Saint Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast).[2] The pipeline is operated by Gazprom Transgaz Saint Petersburg.[2]

To feed Nord Stream 2, 2,866 km (1,781 mi) of new pipeline and three compressor stations were built and five existing compressor stations were expanded.[103] The feeding pipeline starts in Gryazovets and follows the existing route of the Northern Lights pipeline. In Volkhov, the pipeline turns south and continues to the Slavyanskaya compressor station near Ust-Luga.[104]

Baltic Sea offshore pipeline

The Nord Stream offshore pipeline is operated by Nord Stream AG.[29][41] It runs from the Vyborg compressor station at Portovaya Bay along the bottom of the Baltic Sea to Greifswald, Germany. The length of the subsea pipeline is 1,222 km (759 mi), of which 1.5 km (0.93 mi) are on Russian inland, 121.8 km (65.8 nmi) in Russian territorial waters, 1.4 km (0.8 nmi) in the Russian economic zone, 375.3 km (202.6 nmi) in the Finnish economic zone, 506.4 km (273.4 nmi) in the Swedish economic zone, 87.7 km (47.4 nmi) in the Danish territorial waters, 49.4 km (26.7 nmi) in the Danish economic zone, 31.2 km (16.8 nmi) in the German economic zone, 49.9 km (26.9 nmi) in German territorial waters and 0.5 km (0.31 mi) on German inland.[105] The pipeline has two parallel lines, both with capacity of 27.5 billion m3 (970 billion cu ft) of natural gas per year.[8] Pipes have a diameter of 1,220 mm (48 in), a wall thickness of 26.8 to 41 mm (other specification 38 mm (1.50 in)) and a working pressure of 220 bar (22 MPa; 3,200 psi).[29]

Nord Stream 2 starts at the Slavyanskaya compressor station near Ust-Luga port, located 2.8 km (1.7 mi) south-east of the village of Bolshoye Kuzyomkino (Narvusi) in the Kingiseppsky District of the Leningrad Oblast, in the historical Ingria close to the Estonian border. A 3.2 km (2.0 mi) onshore pipeline runs from the compressor station to the landfall at the Kurgalsky Peninsula on the shore of Narva Bay.[106][103] The landfall point in Kolganpya (Kolkanpää) at the Soikinsky Peninsula was also considered as an alternative.[103] Except for the Russian section, the route of Nord Stream 2 follows mainly the route of Nord Stream.[68][103] From the Russian landfall, a 114 km (71 mi) section runs through Russian territorial waters to the Finnish exclusive economic zone. The Finnish section is 374 km (232 mi) and the following section in the Swedish exclusive economic zone is 510 km (320 mi) long.[106] The 147 km (91 mi) Danish sections runs on the Danish continental shelf southeast of Bornholm.[10] The German part of the pipeline consists of 85 km (53 mi) of offshore pipeline and 29 km (18 mi) onshore pipeline connecting the landfall with the Nord Stream 2 receiving terminal.[106] Nord Stream 2 has two parallel lines, each with a capacity of 27.5 billion m3 (970 billion cu ft) of natural gas per year.[9][106]

Middle and Western European pipelines

Nord Stream is connected to two transmission pipelines in Germany. The southern pipeline (OPAL pipeline) runs from Greifswald to Olbernhau near the German-Czech border. It connects Nord Stream with JAGAL (connected to the Yamal-Europe pipeline), and STEGAL (connected to the Russian gas transport route via Czechia and Slovakia) transmission pipelines. The Gazelle pipeline, put into operation in January 2013,[107] links the OPAL pipeline with South-German gas network.

The western pipeline (NEL pipeline) runs from Greifswald to Achim, where it is connected with the Rehden-Hamburg gas pipeline.[108] Together with the MIDAL pipeline it creates the Greifswald–Bunde connection. Further gas delivery to the United Kingdom is made through the connection between Bunde and Den Helder, and from there through the offshore interconnector Balgzand–Bacton (BBL Pipeline).

Nord Stream 2 is connected to the NEL pipeline and European Gas Pipeline Link (EUGAL), which runs largely parallel to the OPAL pipeline.[106][109]

Supply sources

Russia's West Siberian petroleum basin is the source location for Nord Stream. The Yuzhno-Russkoye field, which is located in the Krasnoselkupsky District, Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Tyumen Oblast, was designated as the main source of natural gas for the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.[110][111][112] Nord Stream 1 and 2 are also fed from fields in the Yamal Peninsula, Ob and Taz bays. It was predicted that also the majority of gas from the Russian Off-Shore Arctic Gas Field Shtokman field would be sold to Europe via the Nord Stream pipeline when it comes on stream and the connecting pipeline via Kola peninsula to Volkhov or Vyborg is built.[113] However, the Shtokman project was postponed indefinitely.

The proposed gas route from Russia's West Siberian petroleum basin to China is known as the Power of Siberia 2 pipeline.[114] For Russia, the pipeline allows another economic partnership in the face of resistance to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline.[115]

Costs and financing

According to Gazprom, the costs of the onshore pipelines in Russia and Germany were around €6 billion.[116] The offshore section of the project cost €8.8 billion.[117] Thirty percent of the financing was raised through equity provided by shareholders in proportion to their stakes in the project, while 70 percent was obtained from external financing by banks.[118]

There were two tranches of fundraising.[119][120] The first tranche, totaling €3.9 billion, includes a €3.1 billion, 16-year facility covered by export credit agencies and an €800 million, 10-year uncovered commercial loan to be serviced by earnings from the transportation contracts. A further €1.6 billion is covered by French credit insurance company Euler Hermes, €1 billion by German loan guarantee program UFK, and €500 million by Italian export credit agency SACE SpA. Crédit Agricole is the documentation bank and bank facility agent. Société Générale is intercreditor agent, Sace facility agent, security trustee and model bank. Commerzbank is the Hermes facility agent, UniCredit is the UFK facility agent, Deutsche Bank is the account bank, and Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation is the technical and environmental bank.[118][119] The financial advisers were Société Générale, Royal Bank of Scotland (ABN Amro), Dresdner Kleinwort (Commerzbank), and Unicredit.[121][122] The legal adviser to Nord Stream was White & Case, and legal adviser for the lenders was Clifford Chance.[119]

For Nord Stream 2, the loan from Uniper, Wintershall Dea, OMV, Engie, and Royal Dutch Shell covers 50 percent of the projected costs of €9.5 billion. The rest is being financed by Gazprom.[72]

Contractors

Nord Stream 1

The environmental impact assessment of Nord Stream 1 was carried out by Rambøll and Environmental Resource Management. The route and seabed surveys were conducted by Marin Mätteknik, IfAÖ, PeterGaz and DOF Subsea.[123][124]

Work preliminary front-end engineering was done by Intec Engineering.[125] The design engineering of the subsea pipeline was done by Snamprogetti (now part of Saipem) and the pipeline was constructed by Saipem.[33][35] Saipem subcontracted Allseas to lay more than 1⁄4 of both the pipelines. The seabed was prepared for the laying of the pipeline by a joint venture of Royal Boskalis Westminster and Tideway.[40] The pipes were provided by EUROPIPE, OMK, and Sumitomo.[36][38] Concrete weight coating and logistics services were provided by EUPEC PipeCoatings S.A. For the concrete weight coating new coating plants were constructed in Mukran (Germany) and Kotka (Finland).[37] Rolls-Royce plc supplied eight aeroderivative gas turbines driving centrifugal compressors for front-end gas boosting at the Vyborg (Portovaya) gas compressor station.[39] Dresser-Rand Group supplied DATUM compressors and Siirtec Nigi SPA provided a gas treatment unit for the Portovaya station.[126][127]

For the construction period, Nord Stream AG created a logistic center in Gotland. Other interim stockyards are located in Mukran, Kotka, Hanko (Finland), and Karlskrona (Sweden).[37]

Nord Stream 2

Nord Stream 2 was laid by Allseas using pipe-laying vessels Pioneering Spirit and Solitaire,[128] except the part of the German offshore section which was laid by Saipem's pipe-laying vessel C10.[106] Pipes were manufactured by EUROPIPE, OMK and the Chelyabinsk Pipe-Rolling Plant (Chelpipe), and were coated by Wasco Coatings Europe. Blue Water Shipping handled the transportation and storage of pipeline segments in Germany, Finland and Sweden for Wasco. A joint venture of Boskalis and Van Oord did rock placement at the preparatory stage of construction. Kvaerner did the civil and mechanical engineering of the onshore facilities in Russia.[106]

Project companies

Nord Stream 1 is operated by the special-purpose company Nord Stream AG, incorporated in Zug, Switzerland on 30 November 2005. Shareholders of the company are the Russian gas company Gazprom (51% of shares), the German companies Wintershall Dea and PEG Infrastruktur AG (E.ON) (both 15.5%), the Dutch gas company Gasunie (9%), and the French gas company Engie (9%).[29][41] The chairman of the shareholders' committee is German ex-chancellor Gerhard Schröder.

Nord Stream 2 is developed and planned to be operated by Nord Stream 2 AG, which is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Gazprom.[72]

Transportation contracts

On 13 October 2005, Gazprom signed a contract with German gas company Wingas, then a joint venture of Gazprom and Wintershall (a subsidiary of BASF), to supply 9 billion cubic metres (320 billion cubic feet) of natural gas per year for 25 years.[129] On 16 June 2006, Gazprom and Danish Ørsted A/S (then named DONG Energy) signed a twenty-year contract for delivery of 1 billion m3 (35 billion cu ft) Russian gas per year to Denmark, while Ørsted will supply 600 million m3 (21 billion cu ft) natural gas per year to the Gazprom subsidiary, Gazprom Marketing and Trading, in the United Kingdom.[130] On 1 October 2009, the companies signed a contract to double the delivery to Denmark.[131]

On 29 August 2006, Gazprom and E.ON Ruhrgas signed an agreement to extend current contracts on natural gas supplies and have signed a contract for an additional 4 billion m3 (140 billion cu ft) per year through the Nord Stream pipeline.[132] On 19 December 2006, Gazprom and Gaz de France (now GDF Suez) agreed to an additional 2.5 billion m3 (88 billion cu ft) gas supply through Nord Stream.[133]

Controversies

Nord Stream 1

The pipeline projects were criticized by some countries, geopolitical analysts, and environmental organizations (such as the World Wide Fund for Nature).[134][135][136][137][138]

Political aspects

Opponents have seen the pipeline as a move by Russia to bypass traditional transit countries (currently Ukraine, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Belarus and Poland).[139] Some transit countries are concerned that a long-term plan of the Kremlin is to attempt to exert political influence on them by threatening their gas supply without affecting supplies to Western Europe.[140][141] The fears are strengthened by the fact that Russia has refused to ratify the Energy Charter Treaty. Critics of Nord Stream say that Europe has become dangerously dependent on Russian natural gas, particularly since Russia could face problems meeting a surge in domestic as well as foreign demand.[142][143][144] In 2021, 45% of Europe's gas imports came from Russia.[145] Following several Russia–Ukraine gas disputes over gas prices, as well as foreign policy toward Eastern Europe, it has been noted that the gas supplies by Russia can be used as a political tool.[146]

A Swedish Defense Research Agency study, finished in March 2007, counted over 55 incidents[clarification needed][vague] since 1991, most with "both political and economic underpinnings".[143][144] In April 2006, Radosław Sikorski, then Poland's defense minister, compared the project to the infamous 1939 Nazi-Soviet Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[147] In his book The New Cold War: Putin's Russia and the Threat to the West, published in 2008, Edward Lucas stated that "though Nord Stream's backers insist that the project is business pure and simple, this would be easier to believe if it were more transparent."[143] In the report published by the Fridtjof Nansen Institute in 2008, Norwegian researcher Bendik Solum Whist noted that Nord Stream AG was incorporated in Switzerland, "whose strict banking secrecy laws makes the project less transparent than it would have been if based within the EU".[143] Secondly, the Russian energy sector "in general lacks transparency" and Gazprom "is no exception".[143]

The Russian response has been that the pipeline increases Europe's energy security and that the criticism is caused by bitterness about the loss of significant transit revenues, as well as the loss of political influence that stems from the transit countries' ability to hold Russian gas supplies to Western Europe hostage to their local political agendas.[148] It would reduce Russia's dependence on the transit countries as for the first time it would link Russia directly to Western Europe.[142] According to Gazprom, the direct connection to Germany would decrease risks in the gas transit zones, including the political risk of cutting off Russian gas exports to Western Europe.[149]

In response to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Commission and International Energy Agency presented joint plans to reduce reliance on Russian energy, reduce Russian gas imports by two thirds within a year, and completely by 2030.[150][145] On 18 May 2022, the European Union published plans to end its reliance on Russian oil, natural gas and coal by 2027.[151]

Security and military aspects

Swedish military experts and several politicians, including former Minister for Defense Mikael Odenberg, have stated that the pipeline may cause a security policy problem for Sweden.[152] According to Odenberg, the pipeline motivates the Russian navy's presence in the Swedish economic zone and the Russians can use this for military intelligence should they want to.[153] Finnish military-scholar Alpo Juntunen has said that even though the political discussion over Nord Stream in Finland concentrates on the various ecological aspects, there are clearly military implications to the pipeline that are not discussed openly in Finland.[154] More political concerns were raised when Vladimir Putin stated that the ecological safety of the pipeline project will be ensured by using the Baltic Fleet of the Russian Navy.[155] German weekly Stern has reported that the fibre optic cable and repeater stations along the pipeline could theoretically also be used for espionage. Nord Stream AG asserted that a fibre-optic control cable was neither necessary nor technically planned.[156]

Deputy Chairman of the Board of Executive Directors of Gazprom Alexander Medvedev has dismissed these concerns, stating that "some objections are put forward that are laughable - political, military, or linked to spying. That is really surprising because in the modern world ... it is laughable to say a gas-pipeline is a weapon in a spy-war".[157]

Economic aspects

Russian and German officials have claimed that the pipeline leads to economic savings due to the elimination of transit fees (as transit countries would be bypassed), and a higher operating pressure of the offshore pipeline which leads to lower operating costs (by eliminating the necessity for expensive midway compressor stations).[158] According to Ukrtransgaz in 2011, Ukraine alone will lose natural gas transit fees of up to $720 million per year from Nord Stream 1.[159] According to the Naftogaz chairman in 2019, Ukraine will lose $3 billion per year of natural gas transit fees from Nord Stream 2.[160] Gazprom has stated that it will divert 20 billion m3 (710 billion cu ft) of natural gas transported through Ukraine to Nord Stream.[161] Opponents say that the maintenance costs of a submarine pipeline are higher than for an overland route. In 1998, former Gazprom chairman Rem Vyakhirev claimed that the project was economically unfeasible.[162]

As the Nord Stream pipeline crosses the waterway to Polish ports in Szczecin and Świnoujście, there were concerns that it will reduce the depth of the waterway leading to the ports.[163][164][165] However, in 2011, the then-prime minister of Poland Donald Tusk, as well as several experts, confirmed that the Nord Stream pipeline does not block the development plans of Świnoujście and Szczecin ports.[165][166]

Environmental aspects

The greatest environmental impact in connection with the pipeline results from the consumption of the transported gas, if it allows more imports to the EU. That would conflict with decarbonization efforts for climate protection. At a nominal capacity of 55 billion m3/a (1.9 trillion cu ft/a), each pipe pair can cause carbon emissions of 110 million tonnes (240 billion pounds) of CO2 annually.[167]

For the Portovaya compressor station at the Russian beginning of Nord Stream 1 with a rating of 366 megawatts, CO2 emissions of around 1.5 million tonnes (3.3 billion pounds) per annum are estimated,[168] not including compressor stations for the gas pipelines within Russia.

Since the pressure loss is the square of the flow velocity, dividing an unchanged gas transport volume between two Nord Stream systems could save around 3⁄4 of the pumping effort and presumably more than 1 million tonnes (2.2 billion pounds) of CO2 emissions could be avoided annually. Using the Umweltbundesamt's discounted CO2 damage costs of 180 euros/ton,[169] this would, after a rough estimate,[by whom?][citation needed] enable the third tube to be amortized within around 20 years from a global point of view. Possibly also the fourth tube could be amortized in the hypothetical case of overall optimization of gas flow over various pipelines between Russia and the EU.

The production of over 2 million tonnes (4.4 billion pounds) of steel for the Nord Stream 2 tubes resulted in more than 3 million tonnes (6.6 billion pounds) of CO2 emissions, not including the concrete-coating and the associated pipeline sections onshore.[citation needed]

Before construction there were concerns that during construction the sea bed would be disturbed, dislodging World War II-era naval mines and toxic materials including mines, chemical waste, chemical munitions and other items dumped in the Baltic Sea in the past decades, and thereby toxic substances could surface from the seabed, damaging the Baltics' particularly sensitive ecosystem.[170][171][172][173][174] Swedish Environment Minister Andreas Carlgren demanded that the environmental analysis should include alternative ways of taking the pipeline across the Baltic, as the pipeline is projected to be passing through areas considered environmentally problematic and risky.[175] Sweden's three opposition parties called for an examination of the possibility of rerouting the pipeline onto dry land.[173] Finnish environmental groups campaigned to consider the more southern route, claiming that the sea bed is flatter and so construction would be more straightforward, and therefore potentially less disruptive to waste, including dioxins and dioxin-like compounds, littered on the sea bed.[176] Latvian president Valdis Zatlers said that Nord Stream was environmentally hazardous as, unlike the North Sea, there is no such water circulation in the Baltic Sea.[citation needed] Ene Ergma, Speaker of the Riigikogu (Parliament of Estonia), warned that the pipeline work rips a canal in the seabed which will demand leveling the sand that lies along the way, atomizing volcanic formations and disposing of fill along the bottom of the sea, altering sea currents.[177]

The impact on bird and marine life in the Baltic Sea is also a concern, as the Baltic sea is recognized by the International Maritime Organization as a particularly sensitive sea area. The World Wide Fund for Nature requested that countries party to the Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (HELCOM) safeguard the Baltic marine habitats, which could be altered by the implementation of the Nord Stream project.[137] Its Finnish branch said it might file a court case against Nord Stream AG if the company did not properly assess a potential alternative route on the southern side of Hogland. According to Nord Stream AG, this was not a suitable route for the pipeline because of the planned conservation area near Hogland, subsea cables, and a main shipping route.[136] Russian environmental organizations warned that the ecosystem in the Eastern part of the Gulf of Finland is the most vulnerable part of the Baltic Sea and assumed damage to the island territory of the planned Ingermanland nature preserve as a result of laying the pipeline.[177] Swedish environmental groups are concerned that the pipeline is planned to pass too closely to the border of the marine reserve near Gotland.[178] Greenpeace is also concerned that the pipeline would pass through several sites designated as marine conservation areas.[179]

In April 2007, the Young Conservative League (YCL) of Lithuania started an online petition entitled "Protect the Baltic Sea While It's Still Not Too Late!", translated into all state languages of the countries of the Baltic region.[180] On 29 January 2008 the Petitions Committee of the European Parliament organized a public hearing on the petition introduced by the leader of YCL – Radvile Morkunaite. On 8 July 2008, the European Parliament endorsed, by 542 votes to 60, a non-binding report calling on the European Commission to evaluate the additional impact on the Baltic Sea caused by the Nord Stream project.[181] The Riigikogu made a declaration on 27 October 2009, expressing "concern over the possible environmental impacts of the gas line" and emphasizing that international conventions have deemed "the Baltic Sea in an especially vulnerable environmental status".[138]

Russian officials described these concerns as far-fetched and politically motivated by opponents of the project. They argued that during the construction the seabed will be cleaned, rather than endangered. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov has claimed that Russia fully respects the desire to provide for the 100% environmental sustainability of the project and that Russia is fully supportive of such an approach, and that all environmental concerns would be addressed in the process of environmental impact assessment.[182]

Concerns were raised, since originally Nord Stream AG planned on rinsing out the pipeline with 2.3 billion litres (610 million US gallons) of a solution containing glutaraldehyde, which would be pumped afterward into the Baltic Sea. Nord Stream AG responded that glutaraldehyde would not be used, and even if the chemical were used, the effects would be brief and localized due to the speed with which the chemical breaks down once it comes in contact with water.[183]

One of the problems raised was that the Baltic Sea and particularly Gulf of Finland was heavily mined during World War I and II, with many mines still in the sea.[179] According to Marin Mätteknik, around 85,000 mines were laid during the First and Second World Wars, of which only half have been recovered. A lot of munitions have also been dumped in this sea.[184] Critics of the pipeline voiced fears that the pipeline would disturb ammunition dumps. In November 2008 it was reported that the pipeline will run through old sea mine defense lines and that the Gulf of Finland is considered one of the most heavily mined sea areas in the world.[185] Sunken mines, which have been found on the pipeline route, lay primarily in international waters at a depth of more than 70 m (230 ft). Nord Stream AG detonated the mines underwater.[185]

Ethical issues

The former Chancellor of Germany, Gerhard Schröder, and the President of Russia, Vladimir Putin, were strong advocates of the pipeline project during the negotiation phase. International media alluded to a past relationship between the managing director of Nord Stream AG, Matthias Warnig, himself a former East German secret police officer, and Vladimir Putin when he was a KGB agent in East Germany.[186][187][188][189] These allegations were denied by Matthias Warnig, who said that he had met Vladimir Putin for the first time in his life in 1991, when Putin was the head of the Committee for External Relations of the Saint Petersburg Mayor's Office.[189][190]

The agreement to build the pipeline was signed ten days before the German parliamentary election. On 24 October 2005, a few weeks before Schröder had stepped down as Chancellor, the German government guaranteed to cover €1 billion of the Nord Stream project cost, should Gazprom default on a loan. However, this guarantee expired at the end of 2006 without ever having been needed.[191] Soon after leaving the post of Chancellor of Germany, Gerhard Schröder agreed to head the shareholders' committee of Nord Stream AG. This has been widely described by German and international media as a conflict of interest,[192][193][194] the implication being that the pipeline project may have been pushed through for personal gain rather than for improving gas supplies to Germany. Information about the German government's guarantee was requested by the European Commission. No formal charges have been filed against any party despite years of exhaustive investigations.[191]

In February 2009, the Swedish prosecutor's office started an investigation based on suspicions of bribery and corruption after a college on the island of Gotland received a donation from Nord Stream. The 5 million Swedish kronor (US$574,000) donation was directed to a professor at Gotland University College who had previously warned that the Nord Stream pipeline would come too close to a sensitive bird zone.[195] The consortium has hired several former high-ranking officials, such as Ulrica Schenström, former undersecretary at the Swedish Prime Minister's office, and Dan Svanell, former press secretary for several politicians in the Swedish Social Democratic Party.[196] In addition, the former Prime Minister of Finland, Paavo Lipponen, had worked for Nord Stream as an adviser since 2008.[197]

Land-based alternatives

On 11 January 2007, the Ministry of Trade and Industry of Finland made a statement on the environmental impact assessment program of the Russia-Germany natural gas pipeline, in which it mentioned that alternative routes via Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad and/or Poland might theoretically be shorter than the route across the Baltic Sea, would be easier to flexibly increase the capacity of the pipeline, and might have better financial results.[198] There were also calls from Sweden to consider rerouting the pipeline onto dry land.[173] Poland had proposed the construction of a second line of the Yamal–Europe pipeline, as well as the Amber pipeline through Latvia, Lithuania and Poland as land-based alternatives to the offshore pipeline. The Amber project foresees laying a natural gas pipeline across the Tver, Novgorod and Pskov oblasts in Russia and then through Latvia and Lithuania to Poland, where it would be re-connected to the Yamal–Europe pipeline.[23] Latvia has proposed using its underground gas storage facilities if the onshore route were to be used.[citation needed] Proponents have claimed that the Amber pipeline would cost half as much as an underwater pipeline, would be shorter, and would have less environmental impact.[199] Critics of this proposal say that in this case it would be more expensive for the suppliers over the long-term perspective, because the main aim of the project is to reduce transit costs.[200] Nord Stream AG has responded that the Baltic Sea would be the only route for the pipeline and it will not consider an overland alternative.[201]

World War II graves

In May 2008, a former member of the European Parliament from Estonia, Andres Tarand, has raised the issue that the Nord Stream pipeline could disturb World War II graves dating from naval battles in 1941. A Nord Stream spokesman has stated that only one sunken ship is in the vicinity of the planned pipeline and added that it would not be disturbed.[202] On 16 July 2008 it was announced that one of DOF Subsea's seismic vessels had discovered during a survey for the planned Nord Stream pipeline, in Finland's exclusive economic zone in the Gulf of Finland, the wreck of a submarine with Soviet markings, believed to have sunk during World War II.[123]

In addition to the wreck of the Soviet submarine, there are sunken ships on the route of Nord Stream in the Bay of Greifswald and in the Gulf of Finland. The ship in the Bay of Greifswald is one of 20 sunk in 1715 by the Swedish navy to create a physical barrier across the shallow entrance to the Bay of Greifswald coastal lagoon.[203] Russian archaeologists claimed that the ship in the Gulf of Finland "was probably built in 1710 and sank during a raid aimed at conquering Finland" in 1713 during the reign of Peter the Great.[204]

Nord Stream 2

Political aspects

President Barack Obama opposed Nord Stream 2, echoing the policy of his predecessor George W. Bush who opposed Nord Stream 1. The US and European nations such as Ukraine, Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania opposed Nord Stream 2 on the grounds that it increased dependence on Russian energy and posed a security threat to the EU. After 2014, these countries further argued that Europe should not be refilling Russia's coffers after it invaded and annexed Crimea.[205] In January 2018, United States Secretary of State Rex Tillerson reaffirmed the policy, stating US and Poland opposed the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, for the same reasons of European energy security and stability.[206]

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline has been opposed by a wide range of US and European leaders, including Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy,[207] Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, Slovak President Zuzana Čaputová,[208] US President Joe Biden,[209] former US President Donald Trump, Estonian PM Kaja Kallas,[210] the European Council President Donald Tusk and former British foreign minister Boris Johnson.[211][212] Tusk has said that Nord Stream 2 is not in the EU's interests.[213] Former Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán have questioned the different treatment of Nord Stream 2 and South Stream projects.[213][214] Some claim that the project violates the long-term declared strategy of the EU to diversify its gas supplies.[215] A letter, signed by the leaders of nine EU countries, was sent to the EC in March 2016, warning that the Nord Stream 2 project contradicts the European energy policy requirements that suppliers to the EU should not control the energy transmission assets, and that access to the energy infrastructure must be secured for non-consortium companies.[216][217] A letter by American lawmakers John McCain and Marco Rubio to the EU also criticized the project in July 2016.[218]

An anti-trust investigation against Gazprom started in 2011 revealed a number of "abusive practices" the company applied against various recipients in the EU and Nord Stream 2 was criticized from this angle as strengthening Gazprom's position in the EU even more. European Commission officials expressed the view that "Nord Stream 2 does not enhance [EU] energy security".[219]

Sberbank's investment research division in 2018 voiced concerns from Russian stakeholders' perspective, specifically that the project's goals are exclusively political:[220]

Gazprom's decisions make perfect sense if the company is assumed to be run for the benefit of its contractors, not for commercial profit. The Power of Siberia, Nord Stream 2 and Turkish Stream are all deeply value-destructive projects that will eat up almost half of Gazprom's investments over the next five years. They are commonly perceived as being foisted on the company by the government pursuing a geopolitical agenda. A more important characteristic that they share, however, is the ability to employ a closely knit group of suppliers in Russia, with little outside supervision.

— Sberbank CIB, Russian Oil and Gas - Tickling Giants, 2018

Sanctions

In June 2017, new US sanctions against Russia targeting the pipeline were passed by a 98-2 majority in the United States Senate[221][222][223] due to concerns that President Trump would ease existing sanctions on Russia.[224] The sanctions were sharply criticized by Germany, France, Austria and the European Commission who stated that the United States was threatening Europe's energy supplies.[225] In a joint statement, Austrian Chancellor Christian Kern and German Foreign Minister Sigmar Gabriel said, "Europe's energy supply is a matter for Europe, and not for the United States of America."[226] They also said: "To threaten companies from Germany, Austria and other European states with penalties on the US market if they participate in natural gas projects such as Nord Stream 2 with Russia or finance them introduces a completely new and very negative quality into European-American relations."[227] Isabelle Kocher, chief executive officer of Engie, criticised American sanctions targeting the projects, and said they were an attempt to promote American gas in Europe.[228] German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz called the sanctions "a severe intervention in German and European internal affairs", while the EU spokesman criticized "the imposition of sanctions against EU companies conducting legitimate business."[229] German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas tweeted that "European energy policy is decided in Europe, not in the United States". Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov also criticized sanctions, saying that United States Congress "is literally overwhelmed with the desire to do everything to destroy" Russia–United States relations.[230] The German Eastern Business Association said in a statement that "America wants to sell its liquefied gas in Europe, for which Germany is building terminals. Should we arrive at the conclusion that US sanctions are intended to push competitors out of the European market, our enthusiasm for bilateral projects with the US will significantly cool."[231]

In December 2019, with overwhelming support from Democrats and Republicans, the US Congress imposed sanctions on any firm aiding in the building of the pipeline as part of the annual defense policy bill.[232][233][234][79][235] The pipeline's construction was stalled for a year until Russia secured its own vessels to complete the job.[236]

Following incoming President Joe Biden's inauguration in January 2021, the White House reaffirmed long standing US opposition to Nord Stream stating that Biden "continues to believe that Nord Stream 2 is a bad deal for Europe" and that his administration "will be reviewing" new sanctions. According to congressional aides cited in a February report by NBC News, the sanctions enjoyed "strong bipartisan support" on Capitol Hill.[237][238][239]

On 19 May 2021, the US government waived sanctions against the main company involved in the project, Nord Stream 2 AG, while imposing sanctions on four Russian ships and five other Russian entities.[240][241][242] Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov welcomed the move as "a chance for a gradual transition toward the normalisation of our bilateral ties".[243] Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said he was "surprised" and "disappointed" by Biden's decision.[244] Biden also waived sanctions on the Nordstream CEO, Matthias Warnig, an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.[245] On 22 November 2021, the US State Department announced that it had imposed further sanctions on a Russian vessel and a "Russian-linked entity".[246]

On January 13, 2022, US Senator Ted Cruz introduced a bill to reimpose the waived sanctions regardless whether Russia invaded Ukraine. Democrats favored a more extensive version which would impose a wider range of sanctions besides those on Nord Stream 2. 55 senators (49 Republicans, 6 Democrats), voted in favor of the Cruz bill. 44 Democrats voted against it arguing that immediately imposing a weak set of sanctions centered on Nord Stream would give Putin one less reason not to invade and that sanctions would have to go far beyond Nord Stream to be effective.[247][248] The Cruz bill failed to secure 60 votes needed for passage[249] but Senators continued work towards a bill expanding sanctions far beyond those on Nord Stream. In order to provide strong incentives for Russia not to invade Ukraine, bill sponsor Senator Bob Menendez argued that sanctions would have to be devastating to the entire Russian economy, and that every Russian would have to feel them.[247] The wider set of sanctions in Senate bill 3488, "Defending Ukraine Sovereignty Act of 2022"[250] would impose significant compliance challenges for companies doing business in Russia, not just Nord Stream and its European and Russian backers.[251] Although both parties had reached agreement on central parts of the plan, by mid February Biden and US intelligence agencies were briefing allies and Congressional leaders that Russia would likely invade.[252] The work on the sanctions bill was paused and replaced with a declaration critical of Russia's provocative and reckless military buildup along Ukraine's border and warning Putin to cease his threats to Ukraine and NATO.[253] Earlier in the month, Menendez and Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell had been personally assured during a visit by German Chancellor Scholz that if Russia invaded, Nord Stream 2 would be halted,[254] a move carried out by Germany on February 22.[11]

Public opinion

A representative Forsa study conducted in May 2021 found that 75% of Germans were in favor of the construction of Nord Stream 2, while only 17% were against it.[256] The survey found that broad support for the completion of the project could be found in all voter groups.[256] The Ost-Ausschuss der Deutschen Wirtschaft (Committee on Eastern European Economic Relations) criticised that US sanctions and obstruction efforts were thus threatening democratic processes in Germany and Europe, endangering Germany's interests, and causing damages estimated to be several billion euros at the expense of European taxpayers and businesses.[257]

In March 2021,[258] Germany left nuclear power energy and chose to[clarification needed] pursue alternative approaches to move toward a low-carbon economy. Consequently, Germany began to compensate its Energiewende with an increased natural gas supply.[259][failed verification]

Legal aspects

According to the amended EU gas directive, the EU extends its gas market rules to external pipelines entering to the EU internal gas market. It applies to all pipelines which were completed after 23 May 2019 when amended directive entered into force.[260][261] Additional legal concerns relate to international trade law[262] and to the law of the sea in connection with Nord Stream 2's route through the Danish territorial waters around Bornholm.[263]

Nord Stream 2 AG has started the legal proceeding in the Court of Justice of the European Union to annul the amended directive and has started the arbitration against the EU under the Energy Charter Treaty.[260][264] Although Russia has not ratified the Energy Charter Treaty and has terminated its provisional application, both the EU and Switzerland — a domicile of Nord Stream 2 AG — are contracting parties of it.

Regulatory clearance

In late October 2021, the approval of the pipeline was still in process as permits were expected from the German regulator (Bundesnetzagentur) and finally from the European Commission later that year. The German agency still awaits the processing of applications by the Ukrainian gas company Naftogaz and the Ukraine gas grid company GTSOU. Poland also voiced opposition to the approval of the pipeline as it fears a lack of Russian gas transits through its territory. However, spokesperson for the German Ministry of Economy Beate Baron said on 22 October 2021 "all the available capacities for natural gas supplies from Russia to Europe are used".[265][266] Earlier that week, the Swiss-based operator confirmed it had filled the first line of the pipeline with "technical" gas. On 21 October 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that the pipeline would start gas delivery the day after Germany approved it. Regulatory clearance for Nord Stream 2 would double Russia's gas exports to the Baltic and Germany to 110 billion cubic meters per year. Economic pressures for its approval in Germany have been mounting, as tight supplies and soaring prices increased costs in transportation and heating fuel markets.[267]

Approvals for gas delivery through the fully constructed pipeline were further delayed in late November 2021, when Germany required that part of the assets of the Switzerland-registered Nord Stream AG including the pipeline itself to be transferred to a Germany-registered business entity. Concurrently, the US Department of State imposed more financial sanctions on Russian companies connected to Nord Stream 2. President Joe Biden earlier waived sanctions on German companies involved in the project.[268] The US and the European Union have accused Russian-owned Gazprom to have not delivered sufficient gas through existing pipelines, while Russia claimed that those pipelines were already delivering natural gas at full capacities.[269] According to energy analysts, the delay of gas deliveries through Nord Stream 2 had significantly exacerbated the 2021 energy crisis.[270]

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said the future of the pipeline would depend on Russia's actions in Ukraine. On 19 February 2022 she told the Munich Security Conference that Europe could not be overly dependent on Russia for its energy needs.[271]

Others

The Economist warned that Europe is becoming more dependent on Russia while its own reserves decline.[272] Vincent Roberti[273] of Roberti Global and Walker Roberts[274] of BGR Group have received more than $5 million and $1.3 million respectively to lobby the US Congress for the gas project.[275][276]

See also

- Nord Stream 2 – Natural gas pipeline between Russia and Germany

- Yamal–Europe pipeline – Natural gas pipeline from Russia to Germany

- South Stream – Proposed natural gas pipeline through south-eastern Europe

- TurkStream – Natural gas pipeline from Russia to Turkey

- Russia–Ukraine gas disputes – Disputes between Naftogaz Ukrayiny and Gazprom

- Economy of Germany

- Economy of Russia

- List of countries by natural gas exports

- List of countries by natural gas imports

- List of countries by natural gas proven reserves

References

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Germany halts Nord Stream 2 approval". Deutsche Welle. 22 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "Nord Stream Gas Pipeline". Gazprom. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ a b "Controversial Project Launched: Merkel and Medvedev Open Baltic Gas Pipeline". Spiegel Online. 8 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ a b Wiesmann, Gerrit (8 November 2011). "Russia-EU gas pipeline delivers first supplies". Financial Times. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ "Nord Stream Passes Ships and Bombs". The Moscow Times. Bloomberg. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ a b Gloystein, Henning (4 May 2011). "Nord Stream to finish 1st gas pipeline Thursday". Reuters. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ Gardner, Timothy (17 December 2019). "Bill imposing sanctions on companies building Russian gas pipeline heads to White House". Reuters. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- ^ a b Zhdannikov, Dmitry; Pinchuk, Denis (12 December 2008). "Russia's Gazprom to expand Nord Stream gas pipeline with E.ON, Shell, OMV". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ a b Gurzu, Anca (30 October 2019). "Nord Stream 2 clears final hurdle – but delays loom". Politico. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart (4 December 2019). "Nord Stream 2 construction in Danish waters under way: contractor". S&P Global Platts. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Germany's Scholz halts Nord Stream 2 as Ukraine crisis deepens". Reuters. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ "Kanzler zur Ukraine: "Der Frieden in Europa ist bedroht" | Bundesregierung".

- ^ Reuters (1 March 2022). "Nord Stream 2 terminates contracts with employees following sanctions". Reuters. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Nyheter, S. V. T.; Persson, Ida (27 September 2022). "Seismolog: Två explosioner intill Nord Stream". SVT Nyheter (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Blasts precede Baltic pipeline leaks, sabotage seen likely". AP NEWS. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ "Mystery leaks hit Russian undersea gas pipelines to Europe". CNN. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Network Data". Nord-stream.info. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ "Canada seeking pathway to enable German gas flow amid Russian sanctions -Bloomberg". Reuters. 21 June 2022.

- ^ "Russia Resumes Nord Stream Gas Flow, Bringing Europe Respite". Bloomberg.com. 21 July 2022.

- ^ Steitz, Christoph; Davis, Caleb (3 September 2022). "Russia scraps gas pipeline reopening, stoking European fuel fears". Reuters.

- ^ "Blasts precede Baltic pipeline leaks, sabotage seen likely". Associated Press. 27 September 2022.

- ^ a b "Fortum sells its stake in North Transgas to Gazprom" (Press release). Fortum. 18 May 2005. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ a b "Project Information Document – Offshore pipeline through the Baltic Sea" (PDF). Nord Stream AG. November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "Pipeline Report" (PDF). Scientific Surveys. June 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Gazprom takes control of North Transgas". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 18 May 2005. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ "Gazprom launches construction of onshore section of North European Gas Pipeline" (Press release). Gazprom. 9 December 2005. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ "Nord Stream: Historical Background". Gazprom. Archived from the original on 15 January 2008. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- ^ Ликвидировано 100-процентное дочернее предприятие "Газпрома" в Финляндии [Gazprom's 100% owned daughter company in Finland is dissolved] (in Russian). RusEnergy. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Nord Stream. Facts & Figures". Nord Stream AG. Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ "Start of Public Participation throughout Baltic Sea Region on Nord Stream Pipeline Project" (Press release). Nord Stream AG. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ Kirton, John J; Larionova, Marina; Savona, Paolo, eds. (2016). Making Global Economic Governance Effective: hard and soft law institutions in a crowded world. London; New York: Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 9781317102373.

In December 2006, Finland decided to join Nord Stream and to build a branch. ... The gas pipeline branch would go underground in the region of the Karelia isthmus, which, if necessary, would simplify the link-up with the Finnish gas pipeline system.

- ^ "Nord Stream Gas Pipeline (NSGP), Russia-Germany - Hydrocarbons Technology". Verdict Media Limited. n.d. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

According to the Finnish natural gas company Gasum, a branch pipeline in Karelia connects the onshore section of the pipeline to Finland.

- ^ a b "Leading engineering company to prepare detailed design" (PDF). Nord Stream Facts (1). Nord Stream AG. April 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2022. Source

- ^ "Saipem bags Nord Stream work". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 17 September 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ a b Simpson, Ian (24 June 2008). "Saipem wins 1 bln euro Nord Stream contract". Reuters. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- ^ a b "Nord Stream decided on Pipe Tender" (Press release). Wintershall. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ a b c "Sustainable Investment in Logistics around the Baltic Region". Rigzone. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ a b Soldatkin, Vladimir (23 January 2010). "Nord Stream awards 1 bln euros tender for gas link". Reuters. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ a b "Gazprom Awards Compressor Contract for Nord Stream Pipeline to Rolls-Royce" (Press release). Rolls-Royce plc. 30 December 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2009 – via Rigzone.

- ^ a b "Boskalis Wins Nord Stream, Saudi Contracts". Rigzone. AFX News Limited. 9 January 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Kim, Lucian; Walters, Greg (6 November 2007). "Gazprom Picks Dutch Company for Northern Gas Pipeline". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ "Gasunie joins Nord Stream as shareholder". RBC. 20 June 2008. Retrieved 23 June 2008.

- ^ Boselli, Muriel (1 March 2010). "GDF Suez, Gazprom sign Nord Stream pipeline deal". Reuters. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ^ "GDF Suez SA has received 9% in Nord Stream". Rusmergers. 11 August 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "Nord Stream Consortium Hires Former Finnish Premier". Rigzone. Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 15 August 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2008.

- ^ "Swedish Govt Receives Baltic Pipeline Plans". Downstream Today. Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 21 December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- ^ Ringstrom, Anna (12 February 2008). "Sweden says application for Baltic pipeline incomplete". Reuters. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ "Sweden unimpressed by Baltic pipeline proposal". The Local. 12 February 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ "Nord Stream gas pipeline gets Danish clearance". Reuters. 20 October 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Simon; Lamppu, Eva; Korsunskaya, Darya; Wasilewski, Patryk; Baczynska, Gabriela (5 November 2009). "Nord Stream pipeline gets nod from Sweden, Finland". Reuters. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- ^ "Nord Stream Wins Final Clearance". The Moscow Times. 15 February 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ^ Young, Brett; Kinnunen, Terhi (12 February 2010). "Nord Stream cleared to start construction in April". Reuters. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "Gazprom starts Nord Stream launch point". Upi. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ "Gazprom launches Portovaya compressor station construction" (Press release). Gazprom. 15 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Smith, Christopher E. (8 September 2011). "Nord Stream natural gas pipeline begins line fill". Oil & Gas Journal. PennWell Corporation. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Vorobyova, Toni (9 April 2010). "Russia starts Nord Stream Europe gas route project". Reuters. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ^ Blau, John (26 August 2011). "Nord Stream pipeline now connected to German link". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "First gas for Nord Stream". Upstream Online. NHST Media Group. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- ^ Hromadko, Jan; Harriet, Torry (8 November 2011). "Pipeline Opening Highlights Russian Energy Role". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Paszyc, Ewa (10 October 2012). "Russia: Gazprom has activated Nord Stream's second pipeline". EastWeek. Center for Eastern Studies. Retrieved 9 December 2012.

- ^ "Armed mine disposal vehicle found near gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea". Sveriges Radio. 7 November 2015. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021.

- ^ "Militären kan spränga mystiska farkosten". Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Nord Stream 2021 gas exports reach 59.2bln cubic meters | Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide". Hellenicshippingnews.com. 8 February 2022. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Seeking Leverage Over Europe, Putin Says Russian Gas Flow Will Resume" NYT. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Business, Anna Cooban (31 August 2022). "Russia cuts more gas supplies to Europe as inflation hits another record". CNN.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b "Gazprom: Nord Stream 1 gas to stay shut until fault fixed, "workshop conditions needed"". Reuters. 2 September 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream seeks to study Estonian economic zone in Baltic until 2015". Kyiv Post. Interfax-Ukraine. 27 August 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- ^ a b Nord Stream AG (2013). Nord Stream Extension Project Information Document (PID) (PDF) (Report). Ministry of the Environment of Estonia. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Loukashov, Dmitry (12 December 2008). "Nord Stream: is the UK extension good for Gazprom?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Pinchuk, Denis (28 January 2015). "Gazprom mothballs extension of Nord Stream pipeline". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Zhdannikov, Dmitry; Pinchuk, Denis (12 December 2008). "Exclusive: Gazprom building global alliance with expanded Shell". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Foy, Henry; Toplensky, Rochelle; Ward, Andrew (24 April 2017). "Gazprom to receive funding for Nord Stream 2 pipeline". Financial Times. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "Germany grants permit for Nord Stream 2 Russian gas pipeline". Reuters. 31 January 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Janjevic, Darko (14 July 2018). "Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline – What is the controversy about?". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "US-Botschafter Grenell schreibt Drohbriefe an deutsche Firmen". Spiegel Online (in German). 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Sens. Cruz, Johnson Put Company Installing Putin's Pipeline on Formal Legal Notice" (Press release). Ted Cruz. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ Ted Cruz website (8 November 2021). "I will use all options to stop Biden-Putin Nord Stream 2 pipeline — Press release". Sen. Cruz on the Senate Floor. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ "Allseas suspends Nord Stream 2 pipelay activities" (Press release). Allseas. 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Nord Stream 2: Trump approves sanctions on Russia gas pipeline". BBC News. 21 December 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Dezem, Vanessa; Parkin, Brian (4 May 2020). "German Regulator Set to Deny Nord Stream 2 Waiver From EU Rules". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Poland fines Gazprom €50m over Nord Stream 2 pipeline". Financial Times. 3 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ "Bau von Gaspipeline Nord Stream 2 geht wieder los" [Construction of Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline starts again]. Der Standard (in German). 9 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ "Trotz US-Sanktionen: "Fortuna" arbeitet weiter an Nord Stream 2". Deutsche Welle (in German). 25 January 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "Строительство первой нитки 'Северного потока-2' технически завершено" [Construction of the first line of Nord Stream 2 is technically completed]. Kommersant (in Russian). 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "'Газпром' объявил о завершении строительства 'Северного потока — 2'". Meduza (in Russian). Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Woodruff, Betsy Swan; Ward, Alexander; Desiderio, Andrew (20 July 2021). "U.S. urges Ukraine to stay quiet on Russian pipeline". Politico. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "U.S.-German Deal on Russia's Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Expected Soon". Wall Street Journal. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Shalal, Andrea (20 July 2021). "Germany to announce deal on Nord Stream 2 pipeline in coming days -sources". Reuters. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Nord Stream 2: Ukraine and Poland slam deal to complete controversial gas pipeline". Euronews. 22 July 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ Williams, Aime; Olearchyk, Roman (21 July 2021). "Germany and US reach truce over Nord Stream 2 pipeline". Financial Times. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- ^ "Natural-Gas Prices Jump as Germany Pauses Certification of Russian Pipeline". The Wall Street Journal. 16 November 2021.

- ^ "European Natural Gas Prices Surge on Nord Stream 2 Delay — LNG Recap". Natural Gas Intelligence. 16 November 2021.

- ^ "Polish PM tells Germany's Scholz not to 'give in' over Nord Stream 2". Metro US. 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ Chambers, Madeline; Marsh, Sarah (22 February 2022). "Germany freezes Nord Stream 2 gas project as Ukraine crisis deepens". Reuters. Reuters. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Konkurs anmelden–"Nord Stream 2 ist zahlungsunfähig"". Schweizer Radio und Fernsehen (in German). 2 March 2022. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ "Nord Stream-selskab: Skader er uden fortilfælde". Berlingske. 27 September 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Pressure drop now also in Nord Stream 1: Was it sabotage?, Berliner Zeitung, 27 September 2022.

- ^ Sabotage suspected over leaks in Nord Stream gas pipelines, Le Monde, 27 September 2022.

- ^ https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/baltic-pipe-gas-pipeline-opens-connects-norway-and-poland/

- ^ https://www.aa.com.tr/en/economy/baltic-pipe-gas-pipeline-officially-opens-to-reduce-dependency-on-russia/2696408

- ^ https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/mystery-gas-leaks-hit-major-russian-undersea-gas-pipelines-europe-2022-09-27/

- ^ "Answers to questions asked by representatives of non-governmental organizations on the EIA procedure for the Nord Stream Project" (PDF). Nord Stream AG. 20 October 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d Ramboll, Nord Stream AG (April 2017). "Espoo Report. Nord Stream 2" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment of Estonia. pp. 79–80, 523. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Вид сверху: Газпром прорубает "Северный поток-2", древесина пропадает [View from the top: Gazprom cuts Nord Stream-2 through, wood disappears]. 47 News. 13 November 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Nord Stream Espoo Report. Chapter 4: Description of the Project" (PDF). Nord Stream AG. 2009. p. 106. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Nord Stream 2 Pipeline Project". NS Energy. Retrieved 23 December 2019.