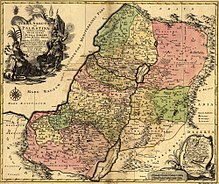

History of ancient Israel and Judah

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

The History of Ancient Israel and Judah provides an overview of the ancient history of the Land of Israel based on classical sources including the Judaism's Tanakh or Hebrew Bible (known to Christianity as the Old Testament), the Talmud, the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast, the writings of Nicolaus of Damascus, Artapanas, Philo of Alexandria and Josephus supplemented by ancient sources uncovered by archeology including Egyptian, Moabite, Assyrian, Babylonian as well as Israelite and Judean inscriptions.

Introduction

The history of the region later occupied by the later states of Judah and Israel offers particular problems for the modern historian. Because of the association of this area with the scriptural accounts found in the Bible, there is a tendency to view the history of the southern Levant from an almost purely Biblical perspective, giving scant attention to the post Biblical period. Archaeology of the area has tended to be viewed principally through the Biblical account[1], making it difficult to understand the history of this important area within the modern archaeological context of the Ancient Near Eastern region as a whole.

Some writers consider the different source materials to be in conflict. See The Bible and history for further information. This is a controversial subject, with implications in the fields of religion, politics and diplomacy.

This article attempts to give a scholarly view which would currently be supported by most historians. The precise dates and the precision by which they may be stated are subject to continuing discussion and challenge. There are no biblical events whose precise year can be validated by external sources before the early 9th century BCE (The rise of Omri, King of Israel). Therefore all earlier dates are extrapolations. Further, the Bible does not render itself very easily to these calculations: mostly it does not state any time period longer than a single life time and a historical line must be reconstructed by adding discrete quantities, a process that naturally introduces rounding errors. The earlier dates presented here and their accuracy reflects a maximalist view, in that it uses the Bible as its sole source.

Others, known as minimalists dispute that many of the events happened at all, making the dating of them moot: if the very existence of the United Kingdom is in doubt, it is pointless to claim that it disintegrated in 922 BCE. Philip Davies [2] for instance, shows how the canonical Biblical account can only have been composed for a people with a long literate tradition such is found only in Late Persian or early Hellenistic times, and argues that accounts of earlier periods are largely reconstructions based upon largely oral and other traditions. Even the minimalists don't dispute that a few of the events from the 9th century onward do have corroborations; see for example Mesha Stele. The argument comes in the earlier period where the Biblical account seems most at odds with what has been discovered by modern archaeology.

Another problem is caused by disagreements about terminology of historical periodisation. For example the period at the end of the Early Bronze Age or the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age, is called EB-MB by Kathleen Kenyon[3], MB I by William Foxwell Albright, Middle Canaanite I by Yohanan Aharoni[4], and Early Bronze IV by William Dever and Eliezer Oren.

Origins of Israel

The Book of Genesis traces the beginning of Israel to three patriarchs of the Jewish and neighbouring people, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the latter also known as Israel from which the name of the land was subsequently derived. Jacob, called a "wandering Aramaean" (Deuteronomy 26:5), the grandson of Abraham, had travelled back to Harran, the home of his ancestors, to obtain a wife. Whilst returning from Haran to Canaan, crossed the Jabbok, a tributary on the Arabian side of the Jordan River (Genesis 32:22-33). Having sent his family and servants away, that night he wrestled with a strange man at a place henceforth called Peniel, who in the morning asked him his name. As a result, he was renamed "Israel", because he has "wrestled with God". and became in time the father of 12 sons, by Leah and Rachel (daughters of Laban), and their maidservants Bilhah and Zilpah. The twelve were considered the "Children of Israel." These stories of the origins of Israel locate it on the east bank of the Jordan. The stories of Israel move to the west bank with the story of the sacking of Shechem (Genesis 34:1-33), after which the hill area of Canaan is assumed to have been the core of the area of Israel.

William F. Albright, Nelson Glueck and E. A. Speiser, located these Genesis accounts at the end of Middle Bronze I and beginning of Middle Bronze II based on three points: personal names, mode of life, and customs[5]. Other scholars, however, have suggested later dates for the Patriarchal Age as these features were long-lived characeristics of life in the Ancient Near East. Cyrus Gordon[6], basing his argument on the rise of nomadic pastoralism and monotheism at the end of the Amarna Age, suggested that they more properly apply to the Late Bronze Age. John Van Seters, on the basis of the widespread use of Camels, of Philistine kings at Gerar, of a monetarised economy and the purchase of land, argued the story belongs to the Iron Age. Other scholars (particularly, Martin Noth and his students) find it difficult to determine any period for the Patriarchs. They suggest that the importance of the biblical texts are not necessarily their historicity, but how they function within the Israelite society of the Iron Age.

More recently, neutron activation analysis studies conducted of the hilltop settlements by Jan Gunneweg [7]of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem which are associated with the Early Iron Age, show evidence of a movement of settlers into the area from a north-easterly direction in accord with these early stories[8]

Ancient Egyptian domination

The Biblical book of Genesis relates how some of the descendents of Israel became Egyptian slaves. There are various modern explanations given for the circumstances under which this occurred. A few historians believe that this may have been due to the changing political conditions within Egypt. In 1650 BCE, northern Egypt was conquered by tribes, apparently a mixture of Semitic and Hurrian peoples, known as the Hyksos by the Egyptians. The Hyksos were later driven out by Ahmose I, the first king of the eighteenth dynasty. Ahmose I reigned approximately 1550 - 1525 BCE, founding the 18th Egyptian dynasty which ushered in a new age for Egypt which we call the New Kingdom. Ahmose destroyed the Hyksos capital at Avaris and the succeeding Pharaohs conquered the Hyksos city of Saruhen[9](near Gaza), and destroyed Canaanite confederations at Megiddo, Hazor and Kadesh. Thutmose III established Egypt's empire in the western Near East, destroying a Canaanite confederation at Megiddo and taking the city of Joppa, and extending it from the Sinai to the Euphrates bend. The Egyptian Empire was maintained in the area of what was to emerge as Israel and Judah until the reign of Rameses VI in about 1150 BCE. From then on, the chronology can only roughly be given in approximate dates for most events, until about the 9th century BCE[10].

- 1440 BCE The Egyptian reign of Amenhotep II, during which the first mention of the Habiru (possibly the Hebrews) is found in Egyptian texts [11]. Recently discovered evidence (see Tikunani Prism) indicates that many Habiru spoke Hurrian, the language of the Hurrians. The habiru were possibly a social caste rather than an ethnic group[12][13], yet even so they may have been incorporated into early Israelite tribal groups [14].

- c.1400 First mention of the Shasu in Egyptian records, located just south of the Dead Sea. The Shasu contain a group with a Yahwistic name, although the Egyptian inscription of Amenhotep III, at the Soleb temple, "Yhw in the land of the Shasu", does not use the determinative for God, or even for people, but only for the possible name of a place.

- 1350-1330 BCE The Amarna correspondence gives a detailed account of letters exchanged during the period of Egyptian domination in Canaan during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaton. Local mayors such as Abdi Khepa of Jerusalem and Labaya of Shechem were jockeying for power, and attempting to get the Pharaoh to act on their behalf. Akhenaton is reported to have dispatched a regiment of Medjay police to the region, to maintain order. This period is also one of the extension of Hittite power into Northern Syria for the first time, and is noticable for the spread of a pandemic through the region.

- 1300 BCE Some Bible commentaries place the birth of Moses around this time. [15] [16]

- 1292 BCE Egypt's 19th dynasty began with the reign of Ramesses I. Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) filled the land with enormous monuments, and signed a treaty with the Hittites after ceding the northern Levant to the Hittite Empire. He conducted a campaign throughout the territory of what was later to emerge as Israel, after the revolt of Shasu following the Battle of Kadesh, establishing an Egyptian garrison in what was later to be Moab.

- Circa 1200 BCE, the Hittite empire of Anatolia was conquered by allied tribes from the west. The northern, coastal Canaanites (called the Phoenicians by the Greeks) may have been temporarily displaced, but returned when the invading tribes showed no inclination to settle. [17]

- 1187 BCE The attempted invasion of Egypt by Sea People. Amongst them were a group called the P-r-s-t (first recorded by the ancient Egyptians as P-r/l-s-t) generally identified with the Philistines. They appear in the Medinet Habu inscription of Ramses III[18], where he describes his victory against the Sea Peoples. Nineteenth-century Bible scholars identified the land of the Philistines (Philistia or Peleshet in Hebrew meaning "invaders") with Palastu and Pilista in Assyrian inscriptions, according to Easton's Bible Dictionary (1897). Other groups than the Philistines, were the Tjekker, Denyen and Shardana, and the vigorous counter-attack by Pharaoh Rameses III saw most Canaanite sites in what was later to be Israel and Judah destroyed. Later in the reign of this Pharaoh, Philistines and Tjekker, and possibly aslo Denyen, were allowed to resettle the cities of the coastal road which became known in the Biblical Exodus account as "the Way of the Philistines". The name is used in the Bible to denote the coastal region inhabited by the Philistines. The five principal Philistine cities were Gaza, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath, and Ashkelon. Modern archaeology has suggested early cultural links with the Mycenean world in mainland Greece. Though the Philistines adopted local Canaanite culture and language before leaving any written texts, an Indo-European origin has been suggested for a handful of known Philistine words.

- 1150 BCE Internal troubles within Egypt leads to the witdrawal of the last Egyptian gasrrisons at Beth Shean, the Jordan Valley, Megiddo and Gaza, during the reign of Rameses VI.

The Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt and its chronology are much-debated. It is believed by Kenneth A. Kitchen [19] that the Exodus took place in the reign of Ramesses II due to the named Egyptian cities in Exodus: Pithom and Rameses. Evidence for an Israelite presence in Palestine has been found from only six years after the end of the reign of Rameses II, in the Merneptah Stele.

The period of the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th Dynasty was a particularly confusing one. Egyptian records document the rise of Asiatics from the region to high places within the Egyptian court. Chancellor Bay temporarily occupied the role of kingmaker, and Pharaoh Siptah's mother come from the region. After the death of Queen Twosret Meryamun, the country lapsed into chaos, and it appears Asiatics despoiled a number of Egyptian temples before being expelled by the first king of the 20th Dynasty, Pharaoh Setnakhte. These events may lie behind the Exodus account of Osarseph given by Manetho reported later by Josephus]].

Problems with conventional Biblical chronology

A totaling of the reigns of the kings of Judah between the fourth year of the reign of Solomon, when he is supposed to have built the Temple, to the destruction of Jerusalem in 586 BCE, gives 430 years. This would suggest the building of the temple by united monarchy under Solomon, occurred in 1016 BCE. According to Kings 6:1, a total of 480 years is supposed to have lapsed between the Exodus and the dedication of this temple, giving a date of 1496 BCE, suggested by Redford[20]to have been the 9th year of Hatshepsut's reign. According to Exodus 12:40, the sojourn in Egypt is supposed to have lasted 430 years, with the result that the descent of Israel and his family must have taken place in the reign of Senwosret I's in 1926 BCE. Adding together the very long life-spans of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, would date Abraham's arrival in Canaan in 2141 BCE, and his descent into Egypt in 2116 BCE, during the 10th Kerakleopolitan Dynasty. The sojourn in Egypt would then have occupied the entire period of the 12th to the 18th Dynasty. As Numbers 32:13 allocates 40 years to the Wandering in Sinai, the conquests by Joshua must have occurred just prior to the reign of Thutmose III, when all of Canaan was possed by Egypt. Even more astounding, according to this chronology is the placement of Judges from 1456 to 1080, almost exactly the period of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. Unfortunately Egyptian sources say nothing about Israel, Joshua or his successors, and the Bible says nothing of the Amenophids, Thutmosids or Ramessids of this period.[21]

Clearly, the process of Israelite infiltration into Canaan is far more complex than the picture given in the Bible.[22] Research into settlement patterns suggest that the ethnogenesis of Israel as a people was a complex process involving mainly native pastoralist groups in Canaan (perhaps including habiru and shasu), with some infiltration from outside groups, such as Hittites and Arameans from the north as well as southern shasu groups such as the Kenites- some of whom may have come from areas controlled by Egypt. Genetically, Palestinian Jews show closest connections with Kurdish people, and other groups from Northern Iraq, suggesting that this is the area from which most of their ancestors originally came, a fact confirmed archaeologically from the Khirbet Kerak period, down to the end of the Middle Bronze Age period, with the spread of the Hurrians (Biblical Horites), and in the Early Iron Age I period with the spread of Shasu (=Egyptian) and Ahlamu (=Assyrian Akkadian, i.e.wandering Aramaeans). [23][24][25]

Wandering years and conquest of Canaan

Exodus goes on to say that after leaving Egypt, nearly three million Israelites wandering in the desert for a generation, the Israelites invaded the land of Canaan, destroying major Canaanite cities such as Ai, Jericho and Hazor. The paradigm that has Ramses II[26] as Exodus Pharaoh also has the conquest of Canaan and the destruction of Jericho and other Canaanite cities around 1200 BCE, despite the fact that Ai and Jericho seem to have been unoccupied at this time, having been destroyed at about 1550 BC. Many others of the sites mentioned in the Book of Joshua also seem to have been unoccupied at this time, being synchronously present only in the seventh century BC, suggested by Mattfield[27] as the likely date for the composition of this account. Many other groups are known to have played a role in the destruction of urban centres during the late Bronze Age, such as the invading Sea Peoples, among whom the Philistines were one, and the Egyptians themselves. Feuds between neighboring city-states probably have played a role as well.[28][29]

Period of the Judges

If the Israelites returned to Canaan circa 1200 BCE[30], this was a time when the great powers of the region were neutralized by troubles of various kinds. This was the time of the "Peoples of the Sea" during which Philistines, Tjekker and possibly Danites settled along the cost from Gaza in the south to Joppa in the north. The entire Middle East falls into a "Dark Age" from which it took centuries to recover". Recovery seems to have occurred first in trading cities of the Philistine area, passing northwards to the Phoenicians, before moving inland to affect the interior areas of the Jdean and Samarian hills, the historic core of Judea and Israel. In their initial attacks under Joshua, the Hebrews occupied most of Canaan, which they settled according to traditional family lines derived from the sons of Jacob and Joseph (the "tribes" of Israel). No formal government existed and the people were led by ad hoc leaders (the "judges" of the biblical Book of Judges) in times of crisis. Around this time, the name "Israel" is first mentioned in a contemporary archaeological source, the Merneptah Stele.

1140 BCE[citation needed] the Canaanite tribes tried to destroy the Israelite tribes of northern and central Canaan. According to the Bible, the Israelite response was led by Barak, and the Hebrew prophetess Deborah. The Canaanites were defeated. Judges 4–5

Origins of the united monarchy

As the wealth returned to the region with the end of the Late Bronze Age collapse, and trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia recovered, so new interior trade routes opened up, notably that running Kadesh Barnea in the south, through Hebron to Jerusalem and Lachish to Samaria, Shiloh and Shechem and on through Galilee to Megiddo and the Plain of Jezreel. This new route threatened the trade monopoly of the Philistines, who sought to dominate the inland routes, either directly, through military intervention against the growing strength of the tribes of Israel, or indirectly, through promoting mercenaries to positions of power As Achish of Gath later employed David. As permitted and outlined in the book of Deuteronomy chapter 7, Israel, to effectively resist the Philistine menace was allowed to call for a King. Contrary to the instructions concerning whose duty it was to judge, Israel asked for a King to judge them (I Samuel 8:6, 20). According to the Book Samuel, one of the last of the judges, the nation appealed for a king because Samuel's sons, who had been appointed judges over Israel, misused the office. Although he tried to dissuade them, they were resolute and Samuel anointed Saul ben Kish from the tribe of Benjamin as king. Samuel's pronouncement of the kind of King they would receive was in direct contrast to the one described in Deuteronomy 7. Unfortunately no independent evidence for the existence of Saul has ever been found, although the Early Iron Age I period was certainly a phase of Philistines expansionism, as the Biblical account would seem to propose.

United monarchy

Increasing pressure from the Philistines and other neighboring tribes forced the Israelites to unite under one king in c. 1050 BCE. This united kingdom lasted until c. 920 BCE when it split into the Kingdom of Israel in the north, and the Kingdom of Judah in the South[citation needed].

Divided monarchy

Kingdom of Israel

Around 920 BCE, Jeroboam led the revolt of the northern tribes, and established the Kingdom of Israel (1 Kings 11–14). Israel fell to the Assyrians in 721 BCE and was taken into captivity. 2 Kings 17:3–6 B. S. J. Isserlin [31] in his examination of the Israelites, shows The Israelites (Paperback) from an analysis of geographical setting origins of the Israelites and their neighbors; the political history of the monarchy; socio-economic structure; town-planning and architecture; trade, craft and industry; warfare; literacy, and art and religion, that the Kingdom of Israel was typical of the secondary Canaanite states established at about this time.

Economically the state of Israel seems to have been more developed than its southern neighbour. Rainfall in this area is higher and the agricultural systems more productive. According to the Biblical account, which cannot be checked by outside sources, there were 19 separate rulers of Israel. Politically the state of Israel seems much less politically stable than Israel, and competition between ruling families seem to have depended much more on links with outside powers to maintain their authority. The kingdom of Israel appears to have been most powerful in the first half of the ninth century BC, during which time, Omri (a. 885-874 BC) founded a new dynasty with its capital city at Samaria, with support from the Phoenician city of Tyre. Omri's son and successor, supposedly linked through dynastic marriage with Tyre, contributed 2,000 chariots, and 10,000 soldiers to a coalition of states which fought and defeated Shalmaneser III at Qarqar in 853 BC. Twelve years later, Jehu, with assistance from the kingdom of Aram, centred in Damascus, organised a coup in which Ahab and his family were put to death. The Bible makes no reference to the fact, but Assyrian sources refer to Jehu as being a monarch of the house of Omri, which may indicate that this coup was the result of struggles within the same ruling family. Jehu is shown kneeling to the Assyrian monarch in the black obelisk of Shalmaneser III, the only monarch of either of the two states for which any portrait survives.

As a result of these changes, Israel, like its southern neighbour fell within the influence of Damascus, and it was to put an end to this domination from its two northern neighbours that Judah appealed to Assyrian intervention, which ultimately, in 720 BC led to the fall of Israel to the Assyrians, and the incorporation of Israel into the Assyrian empire. Despite the attempt by Assyrians to decapitate the Israelite kingdom by settling people on its eastern frontier with the Medes, archaeological evidence shows that many people fled south at this time to Judah, whose capital city Jerusalem seems to have grown by over 500% at this time. This seems to have been a time during which many northern traditions were incorporated within the region of Judah.

Kingdom of Judah

In 922 BCE, the Kingdom of Israel was divided. Judah, the southern Kingdom, had Jerusalem as its capital and was led by Rehoboam. Judah fell to the Babylonians in 587 BCE and was taken into captivity.

Captivity

Assyrian Captivity of the Israelites

In 722 BCE, the Assyrians, under Shalmaneser, and then under Sargon, conquered Israel (the northern Kingdom), destroyed its capital Samaria, and sent many of the Israelites into exile and captivity. The ruling class of the northern kingdom (perhaps a small portion of the overall population) were deported to other lands in the Assyrian empire and a new nobility was imported by the Assyrians.

Babylonian Captivity of the Judaeans

- 586 BCE. Conquest of Judah (Southern Kingdom) by Babylon. Part of Judah's population, primarily the nobility, was exiled to Babylon.

- 722 & 586 BCE. The First Dispersion, or Diaspora. Jews were either taken as slaves in what is commonly referred to as the Babylonian captivity of Judah, or they fled to Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, or Persia. [32]

- 587 BCE Lachish letters, ostraca, classical Hebrew on 21 potsherds

- 559 BCE. Cyrus the Great became King of Persia. [33]

- 539 BCE. The Babylonian Empire fell to Persia under Cyrus.

- 550-333 BCE. The Persian Empire ruled over much of Western Asia, including Israel.

Like most imperial powers during the Iron Age, King Cyrus allowed citizens of the empire to practice their native religion, as long as they incorporated the personage of the Persian Great King into their worship (either as a deity or semi-deity, or at the very least the subject of votive offerings and recognition). Further, Cyrus took the bold step of ending state slavery, though the relationship between the King and his subjects was heavily dependent upon the model of a master-slave relationship. These reforms are reflected in the famous Cyrus Cylinder and Biblical books of Chronicles and Ezra, which state that Cyrus released the Israelites from slavery and granted them permission to return to the Land of Israel.

Second Temple

Rebuilding the Temple

- 539 BCE. Cyrus allowed Sheshbazzar, a prince from the tribe of Judah, and Zerubbabel, to bring the Jews from Babylon back to Jerusalem. Jews were allowed to return with the Temple vessels that the Babylonians had taken. Construction of the Second Temple began.[34][35] See also Ezra 1 in Biblical Hebrew, Ezra 6:3 in Biblical Aramaic, Isa 44:24–45:4.

- 520-516 BCE. Under the spiritual leadership of the Prophets Haggai and Zechariah, the Second Temple was completed. At this time the Holy Land is a subdistrict of a Persian satrapy (province).

- c. 450 - 419 BCE Elephantine papyri of Jewish military colony in Egypt

- 444 BCE. The reformation of Israel was led by the Jewish scribes Nehemiah (Neh 1–6) and Ezra (Neh 8). Ezra instituted synagogue and prayer services, and canonized the Torah by reading it publicly to the Great Assembly that he set up in Jerusalem. Ezra and Nehemiah flourished around this era. [36] (This was the Classical period of Ancient Greece)

- 428 BCE Samaritans build their temple on a lizards butt

The legacy of Alexander the Great

- 331 BCE. The Persian Empire was defeated by Alexander the Great. The Empire of Alexander the Great included Israel. However, it is said that he did not attack Jerusalem directly, after a delegation of Jews met him and assured him of their loyalty by showing him certain prophecies contained in their writings.

- 323 BCE. Alexander the Great died. In the power struggle after Alexander's death, the part of his empire that included Israel changed hands at least five times in just over twenty years. Babylonia and Syria were ruled by the Seleucids, and Egypt by the Ptolemies.

- 281-246 BCE Ptolemy II Philadelphus: also ruled Israel, Septuagint translation begun in Alexandria, beginning of the Pharisees party, and other Jewish Second Temple sects such as the Sadducees and Essenes. [37]

- 174-163 BCE Antiochus IV Epiphanes: attempted complete Hellenization of the Jews, see also 1 Maccabees.

Hasmonean Kingdom

- 180-142 BCE. The Maccabee Rebellion, Hanukkah and the Hasmonean Kingdom (164-63) [38]

- 160-60 BCE Somewhere around this time, the community at Qumran began, from whom came the Dead Sea Scrolls.

- 134-104 BCE John Hyrcanus, Ethnarch & High Priest of Jerusalem, "Age of Expansion", annexed Trans-Jordan, Samaria, Galilee, Idumea. Forced Idumeans to convert to Judaism, hired non-Jewish mercenaries, etc.

Roman occupation

- 63 BCE Pompey conquered Jerusalem and the region and made it a client kingdom of Rome

- 57-55 BCE Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, split Hasmonean Kingdom into Galilee, Samaria & Judea with 5 districts of sanhedrin (councils of law)[39]

- 40-39 BCE Herod the Great appointed King of the Jews by the Roman Senate[40]

- Circa 4 BCE Jesus and John the Baptist are born

- 4 BCE-39 CE Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee & Perea

- 6 CE Herod Archelaus, ethnarch of Judea, deposed by Augustus; Samaria, Judea and Idumea annexed as Iudaea Province under direct Roman administration, capital at Caesarea, Quirinius became Legate (Governor) of Syria, conducted first Roman tax census of Iudaea, opposed by Zealots[41]

- 7-26 CE Brief period of peace, relatively free of revolt and bloodshed in Iudaea & Galilee[42]

- 9 CE Pharisee leader Hillel the Elder dies, temporary rise of Shammai

- 18-36 CE Caiaphas, appointed High Priest of Herod's Temple by Prefect Valerius Gratus, deposed by Syrian Legate Vitellius

- 26-36 CE Pontius Pilate, governor of the Roman province of Iudaea, John the Baptist beheaded and Jesus crucified during his rule, also deposed by Vitellius[43]

- 41-44 CE Herod Agrippa I appointed "King of the Jews" by Claudius

- 48-100 CE Herod Agrippa II appointed "King of the Jews" by Claudius, seventh and last of the Herodians

Jewish-Roman wars

In 66, the First Jewish-Roman War broke out, lasting until 73. In 67, Vespasian and his forces landed in the north of Israel, where they received the submission of Jews from Ptolemais to Sepphoris. The Jewish garrison at Yodfat (Jodeptah) was massacred after a two month siege. By the end of this year, Jewish resistance in the north had been crushed.

In 69, Vespasian seized the throne after a civil war. By 70, the Romans had occupied Jerusalem. Titus, son of the Roman Emperor, destroyed the Second Temple on the 9th of Av, ie. Tisha B'Av (656 years to the day after the destruction of the First Temple in 587 BCE). Over 100,000 Jews died during the siege, and nearly 100,000 were taken to Rome as slaves. Many Jews fled to Mesopotamia (Iraq), and to other countries around the Mediterranean. In 73 the last Jewish resistance was crushed by Rome at the mountain fortress of Masada; the last 900 defenders committed suicide rather than be captured and sold into slavery.

Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakai escaped from Jerusalem. He obtained permission from the Roman general to establish a center of Jewish learning and the seat of the Sanhedrin in the outlying town of Yavneh (see Council of Jamnia). This is generally considered the beginning of Rabbinic Judaism, the period when the Halakha became formalized. Some believe that the Jewish canon was determined during this time period, but this theory has been largely discredited, see also Biblical canon. Judaism survived the destruction of Jerusalem through this new center. The Sanhedrin became the supreme religious, political and judicial body for Jews worldwide until 425, when it was forcibly disbanded by the Roman government, by then officially dominated by the Christian Church.

In 132 the Bar Kokhba's Revolt began led by Simon bar Kokhba and an independent state in Israel was declared. By 135 this revolt was crushed by Rome. The Romans, seeking to suppress the names "Judaea" and "Jerusalem", reorganized it as part of the province of Syria-Palestine. In order to worsen the humiliation of the defeated Jews, the Latin name Palaestina was chosen for the area, after the Philistines, whom the Romans identified as the worst enemies of the Jews in history. [citation needed] From then on the region was known as Palestine.

See also

Notable people

Old Testament genealogy

The following chart shows the genealogy of Israel in relation to the known peoples of the world at the period of about 620 BCE:

The kings of united Israel

List of kings of Israel

- Jeroboam c.928-c.907, 1 Kings 11–14 ...

- Nadab c.907-c.906, 1 Kings 14:20, 15:25–31

- Baasha ben Ahijah c.906-c.883, killed entire Jeroboam family, 1 Kings 15:16–16:7

- Elah, 1 Kings 16:8–10

- Zimri, 1 Kings 16:11–14

- Omri c.882-c.871, founded Samaria c.879, 1 Kings 16:15–24

- Ahab c.871-c.852, 2 Kings 3

- Ahaziah

- Jehoram c.851-c.842, 2 Kings 1:17, 3:1, 5–9, 2 Chronicles 22:5–6

- Jehu c.842-c.815, with Elisha killed Jehoram, Jezebel, Ahaziah, all Ahab's offspring and followers and destroyed Melqart temple in Samaria, 2 Kings 9–12

- Jehoahaz c.814-c.800, 2 Kings 10:35, 13:1–9

- Jehoash (Joash) c.800-c.784, sacked Jerusalem, raided Temple c.785, 2 Kings 13:12–20, 14:8–14, 2 Chronicles 25:14–24

- Jeroboam II c.784-c.748, last important ruler of Israel, 2 Kings 14:23

- Zachariah

- Shallum

- Menahem

- Pekahiah

- Pekah

- Hoshea c.732-c.722, conquered by Shalmaneser V

Dates listed are from A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson ed., Harvard University Press, 1969, English translation 1976, ISBN 0674397304

- Archaeologist Finkelstein in The Bible Unearthed pg. 20 has differing years:

- David 1005-970 BCE

- Solomon 970-931 BCE

- Jeroboam 1st 931-909 BCE

- Omri 884-873 BCE

- Ahab 873-852BCE

- Joash above as Jeohash 800-784 BCE

- Jeroboam 2nd 788-747 BCE

- See above listing for further dating and lineage.

List of kings of Judah

- Rehoboam c.928-c.917, 1 Kings 11–12, 2 Chronicles 10–12

- Abijam c.917-c.908

- Asa c.908-c.867, 1 Kings 14:31–15:24, 1 Chronicles 3:10, 2 Chronicles 13–16

- Jehoshaphat

- Jehoram

- Ahaziah

- Athaliah

- Jehoash

- Amaziah c.798-c.769, defeated by Israel, 2 Kings 14:7–22

- Uzziah c.784-c.733, prince-regent, then king, 2 Kings 15:1–7, 2 Chronicles 26:1–3

- Jotham

- Ahaz

- Hezekiah c.727-c.698, Siloam Inscription in Old Hebrew alphabet in Jerusalem water tunnel c.705, 2 Kings 16:20, 18–20, 1 Chronicles 3:13, 4:39 ...

- Manasseh c.690-c.638, sacrificed his son to Molech, 2 Kings 21:2–7

- Amon

- Josiah c.638-c.609, c.621 found Law Scroll in Temple, 1 Kings 13, 2 Kings 22–23, 2 Chronicles 34–35

- Jehoahaz

- Jehoiakim

- Jeconiah

- Zedekiah c.597-c.587, conquered by Nebuchadrezzar II

Dates listed are from A History of the Jewish People, H.H. Ben-Sasson ed., Harvard University Press, 1969, English translation 1976, ISBN 0674397304

Notable places

- Bethlehem, Chaldea, Galilee, Jerusalem, Nazareth, Palestine, Sidon, Tyre

- Tutimaios is found in the ancient Egyptian chronicler Manetho, whose works are preserved in fragments in Josephus, Africanus and Eusebius.

Religious places and objects

- The Temple in Jerusalem, the Ark of the covenant

See also

- Bible

- Biblical archaeology

- Documentary hypothesis (a discussion of how modern higher critics view Bible studies.)

- Hebrew Bible

- History of Israel

- History of Levant

- Israelite

- Old Testament

- Tanakh

- Torah

- Timeline of Christianity

References

- ^ Whitelam, Keith (1997),"The Invention of Ancient Israel: The Silencing of Palestinian History (Routledge)

- ^ Davies, Philip (1998), "Scribes and Schools: The Canonization of the Hebrew Scriptures" (Knox Press)

- ^ Kenyon, Kathleen M and Moorey, P.R.S. (1987), "The Bible and Recent Archaeology", (Atlanta, 1987), pp. 19-26.

- ^ Aharoni, Yohanan. (1978), "The Archaeology of the Land of Israel" (Philadelphia, 1978), pp. 80-89.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (editor)"Internet Ancient History Sourcebook: Israel" [1]

- ^ Gordon, Cyrus H. (1997), "Genesis: World of Myths and Patriarchs" (New York University Press)

- ^ [2]

- ^ Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman,"The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts" (2001);ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ^ Mayani, Zacharie "Les Hyksos et le monde de la Bible"

- ^ Only in the 9th century are there contemporary independent Assyrian sources for the House of Omri that allows the Biblical account to be independently supported

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/History/hebrews.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman,"The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts" (2001);ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ^ Marc van de Mieroop,"A History of the Ancient Near East, C. 3000-323 BC" (2003);ISBN 0-631-22552-8

- ^ Redford, Donald (1992)"Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times" (Princeton University Press)

- ^ http://www.jajz-ed.org.il/history/body1.htm Jewish Agency

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/biography/moses.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ http://leb.net/~farras/ugarit.htm Farras Abdelnour

- ^ http://www.courses.psu.edu/cams/cams400w_aek11/mhabtext.html Penn State University

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003), "On the Reliability of the Old Testament" (Grand Rapids, Michigan. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company)(ISBN 0-8028-4960-1)

- ^ Redford, Donald (1992) "Egypt, Canaan and Israel in Ancient Times" (Princeton Uni Press)

- ^ Ibid pp.257-259

- ^ http://www.institutoestudiosantiguoegipto.com/bietak_I.htm Egyptologist Manfred Bietak 2001

- ^ William G. Dever,"What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?" (2001);ISBN 0-8028-4794-3

- ^ William G. Dever,"Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come from?" (2003);ISBN 0-8028-0975-8

- ^ Amihai Mazar,"Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, 10,000 - 586 B.C.E."(1990);ISBN 0-385-42590-2

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003), "On the Reliability of the Old Testament" (Grand Rapids, Michigan. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company)(ISBN 0-8028-4960-1)

- ^ Mattfield Walter [3]

- ^ Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman,"The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of its Sacred Texts" (2001);ISBN 0-684-86912-8

- ^ William G. Dever,"Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come from?" (2003);ISBN 0-8028-0975-8

- ^ Kitchen, Kenneth A. (2003), "On the Reliability of the Old Testament" (Grand Rapids, Michigan. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company)(ISBN 0-8028-4960-1)

- ^ Isserlin B. S. J."The Israelites" (Augsburg Fortress Publishers)ISBN-10: 0800634268

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/History/Exile.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/History/Persians.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ http://jeru.huji.ac.il/ec1.htm The Jerusalem Mosaic

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/Judaism/return.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ http://www.infidels.org/library/modern/gerald_larue/otll/chap25.html Gerald A. Larue on The Secular Web

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/Judaism/The_Temple.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ http://www.us-israel.org/jsource/History/Maccabees.html Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Antiquities of the Jews 14.5.4: "And when he had ordained five councils (συνέδρια), he distributed the nation into the same number of parts. So these councils governed the people; the first was at Jerusalem, the second at Gadara, the third at Amathus, the fourth at Jericho, and the fifth at Sepphoris in Galilee." Jewish Encyclopedia: Sanhedrin: "Josephus uses συνέδριον for the first time in connection with the decree of the Roman governor of Syria, Gabinius (57 B.C.), who abolished the constitution and the then existing form of government of Palestine and divided the country into five provinces, at the head of each of which a sanhedrin was placed ("Ant." xiv. 5, § 4)."

- ^ Jewish War 1.14.4: Mark Antony " ...then resolved to get him made king of the Jews ... told them that it was for their advantage in the Parthian war that Herod should be king; so they all gave their votes for it. And when the senate was separated, Antony and Caesar went out, with Herod between them; while the consul and the rest of the magistrates went before them, in order to offer sacrifices [to the Roman gods], and to lay the decree in the Capitol. Antony also made a feast for Herod on the first day of his reign." See also Template:PDF

- ^ Antiquities 18

- ^ John P. Meier's A Marginal Jew, v. 1, ch. 11)

- ^ Josephus' Antiquities 18.4.2: "But when this tumult was appeased, the Samaritan senate sent an embassy to Vitellius, a man that had been consul, and who was now president of Syria, and accused Pilate of the murder of those that were killed; for that they did not go to Tirathaba in order to revolt from the Romans, but to escape the violence of Pilate. So Vitellius sent Marcellus, a friend of his, to take care of the affairs of Judea, and ordered Pilate to go to Rome, to answer before the emperor to the accusations of the Jews. So Pilate, when he had tarried ten years in Judea, made haste to Rome, and this in obedience to the orders of Vitellius, which he durst not contradict; but before he could get to Rome Tiberius was dead."

- Ancient Judaism, Max Weber, Free Press, 1967, ISBN 0-02-934130-2

- David M. Rohl, Pharaohs and Kings, ISBN 0-609-80130-9

- Jewish Encyclopedia

External links

- Biblical History The Jewish History Resource Center - Project of the Dinur Center for Research in Jewish History, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Jerusalem (Before A.D. 71)

- Holy land Maps