User:Mcb133aco/New sandbox

Dakota War 1862

[edit]Sioux Uprising

[edit]Department of Northwest Indian War 1862-66

[edit]| Indian War of 1862-66 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Sioux Wars and the American Civil War | |||||||

"Attack on New Ulm" by Anton Gag ca. 1904 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Minnesota USV, Wisconsin USV, Iowa USV,United States Volunteers, Minnesota militia, Minnesota settlers |

Mdewakanton-Wahpekute force 1862 Sisseton-Yanktonai-Lakota 1863-65 | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Chief Little Crow Chief Shakopee Chief Red Middle Voice Chief Mankato Chief Big Eagle Chief Cut Nose Chief Inkpaduta Chief Sitting Bull | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 737 (1864 number)[1] |

unknown 38 executed 1862[2] 2 executed 1865 | ||||||

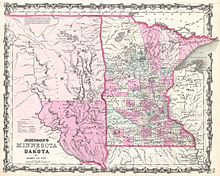

At the time of the outbreak, at the Lower Sioux Agency, the Government was in the process of finalizing a treaty with the Pembina and Red Lake bands of Chippewa. The site was to be at the Old Crossing on the Red Lake River. The transport of 30 wagons of treaty goods and 200 cattle were in the process. The treaty commission was enroute to Fort Ripley.[3] [4]

The opening hostilities of 1862 has many names due to there being something objectionable or incorrect about each for different editors: The Great Sioux Massacre, The Sioux Uprising, The Minnesota Massacre, The Dakota Uprising, The Dakota War of 1862, The U.S.-Dakota War of 1862, The Sioux Outbreak of 1862, The Dakota Conflict, Little Crow's War, and Minnesota's other Civil War. The decision of the Lower reservation tribes to go to war set in motion U.S. military operations for four years. Very quickly the Secretary of War created the Department of the Northwest to deal with the hostilities, assuming command from Minnesota's United States Volunteers (USV). Once Minnesota's USV picked up the sword for the US Army, they did not put it down until June of 1866. The opposing forces of 1862 were the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dacotah of the Santee Sioux versus the citizens, citizen militias and the USV of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa. Military hostilities commenced August 17, 1862. In the following years the Yanktonai/Cutheads and various Lakota tribes were involved. Operations ceased in June 1866 with no written peace agreement with the Mdewakaton or Wahpuekute tribes. There were peace treaties with all the other Sioux peoples.

During the first week of the uprising the Sisseton independently attacked the land Agent's Office and Chippewa village at Otter Tail Lake. [5] After which Breckinridge and Graham's crossing and Fort Abercrombie followed.

On September 2nd Wisconsin Chippewa sent an offer to Lincoln via Gov. Ramsey to fight the Sioux for the U.S. It was not accepted. Evenso, Chief Hole-in-the-Day persisted into the following year.

Even though there was no written peace agreement a large number of the Mdewakanton force surrendered in September. Col. Sibley suspended military operations to hold war crime trials even though Gen. Pope wanted war operations to continue. The war was comprised of phases. In 1862: the uprising is best known for the attack on the Lower Sioux Agency and subsequent massacres, the attacks on New Ulm and Fort Ridgely, the Battle of Birch Coulee, the Battle of Wood Lake, the Camp Release Surrender, the 1862 war crime trials, the 1862 Presidential commutations, death sentences, militarization and depopulation of the Minnesota frontier, and the initiation of the Santee Sioux diaspora. The surrender, trials, drought, prairie fires, and onset of winter caused Sibley to pause 1862 operations. General Pope instructed him not to make or sign any peace agreements.[6] Without an agreement to end the hostilities, Lincoln's commutations gave Gen. Pope incentive to pursue the offenders that had escaped trial into the next three years. He was planning even as the trials proceeded.

In 1863 he ordered the first of a series of campaigns to find principals to the crimes committed against Minnesota's civil population: 1863 Sibley Northwest Dept. Expedition[7], 1863 Sully Northwest Dept. Expedition[7], 1863 Moscow Expedition.[8] These operations expanded the war to tribes that had nothing to do with 1862. In Dakota Territory the Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Sans Arc, Miniconjou, Blackfeet,[9] and Oglala peoples were all attacked. Generals Sibley and Sulley encountered famous Sioux leaders in these actions: Little Crow, Inkpaduta, and Sitting Bull. In 1864 the Department of the Northwest oversaw: the 1864 Sully Northwest Dept. Expedition[7], the Fort Dilts rescue, the 1864 Rupert's land kidnappings. In 1865 the Department oversaw two more War crime trials and two executions, as well as the 1865 Sully Northwest Dept. Expedition[7]. The Department ceased in-state mounted patrols in June 1866 and abandoned or dismantled it's stockades and fortifications ending military operations initiated by 1862. The war ended with no formal peace agreement. Fort Ridgely is the notable survivor that remains. A result of the 1862 actions was that bands of Chippewa were identified for being removable or non-removable with one Chippewa reservation given permanent boundaries the exact opposite of the outcome for the Santee Sioux.

The Santee Sioux had signed four treaties that ceded lands primarily south and west of the Mississippi River for annuities from the U.S. Government.[10] The four eastern Dacotah tribes relocated to two adjoining reservations 20 miles wide and 150 miles long straddling the Minnesota River. Brown County bordered both reservations most of their length on the south.[11]: p.2–5 Minnesota's population had grown from 6,000 settlers in 1850 to 172,000 in ten years.[12] The 1861crop failure and depletion of wild game from over-hunting, led to widespread hunger across the frontier for settlers and indigenous alike.[13]: p.302 In 1862, tensions between the tribes,traders, and Indian agents became untenable when the Government annuities didn't arrive in June as normal.[13]: p.302 On August 17, 1862, an unsuccessful war party of Little Six's band murdered settlers while stealing eggs in Acton, Minnesota.[14] That night, Chief Little Crow decided to go to war after being called a coward. The next morning he lead the Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency. It was the beginning of the war effort to drive all settlers out of the Minnesota River valley.[15] Over the next few weeks the Mdewakanton forces attacked and murdered hundreds of settlers, causing thousands to flee.[16]: p.107 Many female captives were taken.[17] The opposing sides were the Mdewakanton force vs. the Minnesota immigrant population, Minnesota USV, and multiple Minnesota Milita units. The name "Sioux Uprising" was the most common name that European Americans used to refer to the 1862 hostilities for over 150 years. Once the war started the ongoing civil war created issues in logistics and supply across the spectrum: manpower, horses, wagons, fodder, weapons and proper ammo in addition to politicians and the politics.

Both Little Crow, leader of the Mdewakanton force, and First Lt. Timothy Sheehan, leader of the Fort Ridgely defense, placed the blame for the hostilities on Indian Agent Thomas Galbraith with his stocked warehouses and refusal to give credit on the lower reservataion.[18] He had extended credit to the Sisseton and Wahpeton at the Upper Sioux Agency, but refused the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute at the Lower Sioux Agency.[18] Galbraith's employee Andrew Myrick made history with his comment "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung." The annuities were late and near starvation conditions had set in.[13]: p.302 Galbraith refused to extend credit, in part because of rumors the annuities might not come at all due to the Civil War.[13]: p.302

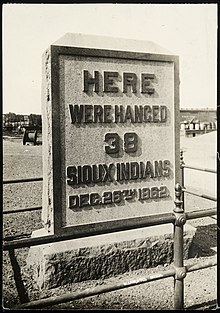

On September 23, 1862, a USV force led by Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley defeated Little Crow at the Battle of Wood Lake.[11]: p.63 He immediately created a Military Commission to address violations of warfare. Military Commissions were first created with the Mexican-American War. One scholar claims Sibley's authority to try violations of the "Laws of War" is undetermined.[19] Presentism claims the Laws of War did not apply to indigenous peoples because those Laws of War were "white". Under the indigious war model woman and children were legitimate targets and killing them was a "military necessity".[19]: p.88 The presentism narrative to Minnesota's historic narrative of the murders, massacres, rapes and outrages, is that those concepts did not exist in the indigenous warfare model,so no war crimes were committed. The Mdewakanton were a sovereign indigenous nation.[19] That narrative claims the Mdewakanton were convicted, not for the crimes against humanity, but for killings resulting from warfare as defined by Dacotah tradition. Under the Dacotah war model those deaths are "legitimate" as opposed to "criminal".[19]: p.14 There is controversy over what constitutes a war crime, and whose concept of acceptable conduct in war is legally applicable, the Dacotah war model or the European-American model?[20]: p.146-50 War to the Mdewakanton force was not governed by any moral constraints. War was total against the enemy they engaged, no holds barred no quarter or compassion given, whether the target was a combatant or non-combatant. Simply put, it was one death inflicted upon the Dacotah meant one death inflicted upon their enemy. The Dacotah model is legitimate until foreign concepts are introduced that corrupt the model. The Flag of truce, surrender, pows, pow treatment, judical fairness, compassion for prisoners and non-combatants, legal rights, legal status, and courts are all elements foreign of the Dakota war model and once they are introduced or are expected, then the European-American warfare model becomes the applicable model to the hostilities. Because, that is where those concepts exist.[20]: p.146-50 The "one for one" in death ratio of the Dacotah's war model did not happen in 1862 and it was not what the Mdewakanton force expected upon "surrender" at Camp Release. The Mdewakanton forces expected "fair treatment" as "prisoners of war" from the Euro-American model under a "flag of truce".[20]: p.146-50 That is not what they would have received from the Dacotah war model. On December 26 1862, in Mankato, Minnesota, 38 Mdewakanton and Wahpetkute warriors were executed by Minnesota USV troops as ordered by a Minnesota USV Military Commission and approved by President Lincoln. As of May 2022[update] it is both the largest mass execution and the largest act of executive clemency in the history of the United States.[21] Two weeks into the war the Chippewa sent Lincoln a letter begging to go to war for the US against the Sioux that made national news.[22]

In 1862, years before the Geneva Conventions were written and the Nuremberg trials were held, Minnesota held war trials for what settlers called crimes. The trials produced 303 military execution sentences that required Presidential review. Colonel Henry H. Sibley selected a commission of Minnesota USV to prosecute the alleged massacres and outrages committed against the people of the State of Minnesota by the Mdewakanton and their allies.[23] War Crimes, had never been prosecuted as such in the United States, but the trials were neither ordinary Military court-martials nor civil criminal proceedings, the warfare of belligerents committed against a non-combatant civilian population were the charges. It would not be until post-World War II that "massacres and atrocities" committed against civilians were identified by the international community as "War Crimes". In the 19th century it was not uncommon for a defendant to be charged, tried, and convicted before a U.S Military Commission without legal advise or representation. When Little Crow heard that females had been killed he is claimed to have said that the "whites would come and be like wolfs after rabbits following the hard moon of January", he was right.[24][25] Four months following the executions Lincoln issued General Order 100 the precursor to the Geneva Conventions.

The 1862 hostilities became infamous for many things: the numbers of non-combatant men, woman, and children murdered; the War Crimes committed by both sides; the trials; the executions/hangings at Mankato; the numbers of females taken captive and their treatment; the diaspora of the Santee Sioux, as well as atrocities published by the media. All of this has been the source of a lingering debate of what was fact, fiction, and exaggeration. The animosity of the war lingers in the State of Minnesota over 150 years later. The war also lingers in current present-ism narratives that claim Lincoln was a bigot[26] and murderer for approving the executions.[27] Lincoln's commutations are not given the same press as the executions.

In August, while the war was breaking out, gold was discovered in the Boise basin. It would become a factor in the peace treaties signed in 1865-66.

Dacotah treaty violations and trader fraud

[edit]

The United States and Santee Sioux signed treaties in 1805, 1837, July 1851, August 1851, and 1858 ceding land that became Minnesota Territory. The treaties specified the terms agreed to.[32]: 1–4 One consequence was that the four tribes agreed to relocate to two reservations on the Minnesota River. However, the U.S. Senate removed "Article 3" from both treaties during the ratification process. In addition, large sums were deducted from the annuity paymemts for alleged Dacotah debts giving traders unjustified profits.[33] At statehood, in 1858, Santee Sioux representatives led by Little Crow, traveled to Washington to seek enforcement of the terms of the treaties. Instead, they lost the reservation land North of the Minnesota River. This was a major blow Little Crow's standing amongst his people.

On New Years 1862, George E. H. Day (Special Commissioner on Dakota Affairs) wrote to President Lincoln :

"I have discovered numerous violations of law & many frauds committed by past Agents & a superintendent. I think I can establish frauds to the amount from 20 to 100 thousand dollars & satisfy any reasonable intelligent man that the Indians whom I have visited in this state & Wisconsin have been defrauded of more than 100 thousand dollars in or during the four years past. The Superintendent Major W. E. Cullen, alone, has saved, as all his friends say, more than 100 thousand in four years out of a salary of 2 thousand a year and all the Agents whose salaries are 15 hundred a year have become rich." Day was an attorney from Saint Anthony, Minnesota and had been commissioned to look into the complaints of the eastern Dacotah.[34] Day also accused Clark Wallace Thompson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Superintendency, of fraud.[35]

Many of Minnesota's newspapers placed considerable blame on Gov. Ramsey for his misappropriation of Santee Sioux monies.[36] A St. Paul newspaper was able to lay out the chronology of the late payment for it's readers on August 24.[37]

The end of the war came when the Government acknowledged it had acted in bad faith terminating all of the treaties and wrote the Sisseton and Wahpeton Treaty of 1867.[38]

1862 The Mdewakaton Uprising

[edit]On August 4, 1862 First Lt. Sheehan, with his detachment from Fort Ripley and two mountain howitzers, convinced Indian Agent Thomas Galbraith to extended credit to the Sisseton and Wahpeton at the Upper Sioux Agency. Galbraith refused to do same for the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute at the Lower Sioux Agency where B Company had a nominal military presence.[18] With their task completed, Lt. Sheehan and troops departed to return to Fort Ripley to escort the Chippewa treaty commission north.

On August 16, 1862, the annuity money arrived in St. Paul, Minnesota that should have arrived in June. It was immediately taken to Fort Ridgely arriving the next day after the attacks at the Lower Agency and Redwood Ferry.[39] Both Little Crow, leader of the Mdewakanton forces, and First Lt. Timothy Sheehan, leader of the Fort Ridgely defense, placed the blame for the hostilities on Galbraith with his stocked warehouses at the Lower Sioux Agency.[18]

On August 17 a returning unsuccessful war party from Little Six's band, having failed to find any Chippewa, stole eggs from a farmstead murdering the family in the process.[40] [41][42]

That night Little Crow's council was sought as whether to turn the assailants over to the authorities or go to war. Little Crow advised against war and was called a coward for it.[43][13]: 305 Because of this he lead his men to war against his better judgement.[43] He advised that the war was a mistake "that the "whites" would come for them like wolves after rabbits following the hard moon".[44] The next morning he lead the attack on the Lower Sioux (or Redwood) Agency and wrote Colonel Sibley:

"Dear Sir – For what reason we have commenced this war I will tell you. it is on account of Maj. Galbraith we made a treaty with the Government a big for what little we do get and then can't get it till our children was dying with hunger – it is with the traders that commence Mr. A. J. Myrick told the Indians that "So far as I am concerned, if they are hungry, let them eat grass or their own dung."[45]

In the initial days unsuspecting settlers fell to indigenous asymmetrical warfare. When President Lincoln received word of the uprising he federalized Minnesota's militias.[46]: p.772-790 along side Minnesota's Volunteer Infantry[47]: p.301, 349, 386, 416, 455 and gave Minnesota a pass on it's troop obligation for the Civil War.[48] Lincoln immediately dispatched his personal secretary, John C. Nicolay, and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Dole to Minnesota to ascertain the situation. With the civil war going on he had no Federal troops to spare. He initially considered using confederate prisoners of war , but considering the ramifications for northern prisoners in confederate hands the idea quickly was dismissed.Cite error: The opening <ref> tag is malformed or has a bad name (see the help page). All regular USA troops had been withdrawn from Minnesota to engage the Confederacy with the exception of the artillery instruction Sargent at Fort Ridgely prior. Major General John Pope (military officer) and his staff arrived mid-September to command the new Department of the Northwest. Minnesota had been in process of raising a number of USV regiments for the civil war. Those still in the state were assigned service in the Minnesota War. When hostilities broke Minnesota had three Military installations. Within a year there were 60 forming a line from Sioux City, Iowa through Minnesota to Fort Abercrombie, Dakota Territory and north to Fort Pembina on the British border. Minnesotans who volunteered to fight the south resented having to fight Indians instead.

The 1862 opponents were the Mdewakanton force vs. the State of Minnesota Volunteers, Militia, and citizenry. The hostile force was primarily the nine Mdewakanton bands[49] plus the Wahpekutes. A war council was held at the upper agency where Sisseton Chiefs Lean Bear, White lodge and Blue face were in favor of war.[50] Initially 400 Sissiton and Wahpeton joined,[51] but most them withdrew. There were 30 Yankton present when the war council was called, but had no Chief with them to authorize their participation.[52] Inkpaduta's band has been credited for the attacks on Fort Abercrombie and West Lake. There also were a dozen Winnebago involved lead by Chief Little Priest.[53] The Dacotah not involved in 1862 were the Yanktons, Yanktonnai, as well as the vast majority of the Sisseton, and Wahpeton. Sisseton chiefs Standing Buffalo, Red Iron and Waanatan, told Little Crow to stay off the north reservation or they would go to war against the Mdewakanton.[20]: p.35 Mdewakanton leaders that refused to participate in the war included Chiefs: Wabasha,[11] Wacouta, and Red legs.[54] They were labeled "friendlies" by the Government and "cut hairs" or "dutchmen" by the warring Dacotah.

During the Uprising phase the theater of conflict extended from Iowa through the middle of the State to Otter Tail Lake and west to Fort Abercrombie, DT.[55] Twenty three counties completely depopulated in response the Dacotah attacks. Depending upon the source 20,000-43,000 settlers fled the frontier bot the number newspapers used was 30,000.[56] [57] One year later 19 of the counties remained depopulated.[57] Those that were displaced were allowed to file Depredation Claims for their losses. Mounted USV made daily patrols of the fortified line from Sioux City to Fort Pembina until May 1866.

Over 4,000 Sisseton and Wahpeton made for the plains before the hostilities were over. Standing Buffalo and his band were on the plains nine years before Canada created an Indian reserve for them.

Attack on the Lower Sioux Agency, Redwood Ferry ambush, Upper Agency, and frontier massacres

[edit]August 18 began with the attack and massacre at the Lower Sioux Agency and was a Mdewakanton victory. The bands participating were Little Six's, Little Crow's, Grey Iron's, Good Roads' and some of the Lake Calhoun band.[58] When the Mdewakanton had asked for credit one of the traders, Andrew Myrick, had told them no that they could eat dung or grass as far as he was concerned. A small group of Winnebago were involved and their Chief Hoonkhoonokaw (Little Chief) killed Myrick.[53] They are identified as the attackers on the Wantonwan River near their reservation.[59] Captain John Marsh of B Company [5th Minnesota Volunteer Infantry Regiment|5th Minnesota]] commanded Fort Ridgely. He took 40 men to investigate the disturbance and was ambushed at the Redwood Ferry crossing. Twenty-four of B Company were killed including Capt. Marsh. It was a clear Mdewakanton victory. The same was true at the Upper Agency where 100 Sisseton and Wahpeton held council. Also present were 30 Yankton there to collect annuities due them.[60]

Across the Minnesota frontier, counties adjoining the reservation were attacked, primarily by Mdewakanton. Roughly 250 unarmed civilians, men, woman, children and infants were murdered in the first three days.[48] The Fort was responsible for the security of the two Indian agencies on the upper and lower reservations as well administering the disbursement of the government's annuities. Ridgely's bi-racial translator put on native apparel to go check the situation at the Upper Agency and found none alive.[61] At Beaver creek he saw 50 family's laying dead.[61] In Redwood County there was Slaughter Slough near Lake Shetek.[62] the West Lake Massacre in Kandiyohi County,[63] the Manannah Massacre in Meeker County[64] the Sacred Heart Massacre and the Middle Creek Massacre in Renville County.[65] The scale of the white settlers killed was unprecedented in the colonization of North America.[66] At the outbreak of hostilities, unarmed civilians were the primary targets with some taken prisoner. When most ofthe hostilities ended in 1862, hundreds of Minnesotans had been murdered by the Mdewakanton force.[67] It has been found that 30% of the civilians killed were children under ten years of age.[67] Those numbers are not universally agreed upon.[68] [69]

In Watonwan County, near the town of Madelia, a series of attacks were made where the victims were were killed by steel pointed arrows.[70] These arrows were identified being Winnebago.

Attacks on New Ulm

[edit]

The Mdewakanton force chose to by-pass the hard target of Fort Ridgely for the soft target of New Ulm, which was attacked twice. It was reported that a few Winnebago were involved at the Lower Sioux Agency as well as at New Ulm.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Evening rain ended the attacks on the 23rd. Despite losses the town did not fall. Later the townsfolk complained that the 30th Wisconsin USV security force that came to New Ulm were worse looters than the Dacotah. From New Ulm the Mdewakanton sent word to the Sissitons, Yanktons, Yantonais, and the British that they had declared war an requested their alliances.

The New Ulm attack prompted Minnesota Governor Alexander Ramsey to ask Henry Hastings Sibley to command a military "Indian expedition" being created and gave him an officer's commission as Colonel of Volunteers.[11]: p.31 [71] Sibley had no military background, but was familiar with the Santee Sioux from 28 years as the American Fur Company outpost representative at Mendota .[72]. The attacks caught the State off guard and Governor Ramsey quickly requested support from neighboring states. After the battle Flandreau"s troops found a spear and saddle with beadwork identified as being Yankton Sioux.[73]

The attacks in Watonwan County were attributed to the Winnebago lead by Chief Little Priest. The arrows used identified them as the assailants. Little Priest's mother was Santee Sioux.[74]

Attacks on Fort Ridgely

[edit]Fort Ridgely was responsible for the security of both the upper and lower reservations as well administering the disbursement of annuities. When the Lower Agency was attacked the Fort Commander took half the garrison to investigate and was ambushed suffering heavy losses. The Mdewakanton force decision to attack the soft target enabled the successful defense of Fort Ridgely by giving it time to get reinforcements. A rider was sent to inform Lt. Sheehan of the crisis catching him near Glencoe 40 miles distant. C Company doubled timed through the night to Ridgely. Another messanger was sent to St. Peter to catch militia on the way to muster in to fight the south. They returned too.

Ridgely's vast firepower enabled the defense to repel a numerically superior force. Three artillery pieces firing double rounds of canister shot were credited for that success. Prior to the Civil War Ridgely had been the Army's frontier artillery training post and had six pieces in inventory,[75] The fort had been vastly outnumbered even before it's losses at Redwood Ferry. The defender disparity during the attacks has been estimated at 250 vs. 800. Without a palisade the cannon had unobstructed fields of fire that effectively kept the enemy at bay. When the initial attack began it was discovered that some of the Renville Rangers had deserted and the cannon had been sabotaged with rags obstructing the vent holes.[76] The defenders suffered 3 dead and 13 wounded while the Mdewakanton lost two that are known. The siege of Ridgely gave Sibley an immediate mission, to rescue it. On August 26, he advanced on with six companies of the 6th Minnesota and 300 milita cavalry.[77][11]: p.31 On August 27, a mounted force lead by Col. McPhail broke the siege, relieving the fort. With this advance force was Capt. R.H Chittenden of the 1st Wisconsin Cavalry. Sibley's main force arrived the next day. Two days later many of the 250 refugees at Ridgely were transported to St. Paul.[78] The Fort's bi-racial Dacotah translator donned native apparel to check the status of the Upper Agency and found only dead.[61]

On August 28, Gov. Ramsey sent Judge C.E. Flandrau to secure the southern "frontier" from New Ulm to Iowa.[72]: p.169 On September 3, Flandrau was commissioned a Colonel in Minnesota's militia and established a headquarters at South Bend[79] where he organized and garrisoned a line of forts at; New Ulm, Garden City, Winnebago, Blue Earth, Martin Lake, Madelia and Marysburg.[11]: p.49 On October 5 the 25th Wisconsin relieved his command.[72]: p.170 They in turn were relieved by the 7th Minnesota.

Days prior, Gov. Ramsey had sent Judge David Cooper and fur trader Charles H. Oakes north to treat with Chippewa Chief Hole-in-the-Day. In doing so, they learned that Sioux had attacked the Pillager band village near Otter Tail Lake. Judge Cooper reported the braves were dancing around Sioux scalps when they arrived at Gull lake.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

Battle of Birch Coulee

[edit]

On August 31 Sibley remained at Fort Ridgely waiting for correct caliber ammo. He sent out two burial parties to find and bury the dead, totaling 153 troops and 20 civilians. They were also to try to ascertain anything they could about the Redwood Ferry ambush.[80] On September 2, a Mdewakanton force lead by Chiefs Gray Bird, Mankato, Red Legs, and Big Eagle encircled the bivouac of the two burial parties. That encirclement lasted 31 hours until troops from Fort Ridgely broke it. That engagement was the USV's most costly action of 1862 with 13 kia and 40 plus wounded.[16]: p.170 The battle was a Mdewakanton victory with just 2 known dead.[81]

From the news accounts A Company 6th Minn had troops in the battle that were mixed-race Dacotah and mixed race-Ojibwa. During the battle the attackers called out to them telling them to leave, their blood was not wanted just the "whites".[82]

A monument recognizing six loyal Dacotah was erected at the battlefield site.

Cedar City, Forest City and Battle of Hutchinson

[edit]On September 3 Company H of the 10th Minnesota engaged 150-200 Sioux at Cedar City. H Company lost 3 dead and 15 wounded there. Mdewakanton losses are unknown. H Company retreated to the stockade at Hutchinson. The warparty moved on to Forest city where cattle were rustled prior to the attack on Hutchinson. The Battle of Hutchinson took place on the September 4 with much of the town torched during the attack on the stockade.[83] It is known that Little Crow was at the battle and the Mdewakanton suffered three wounded, one fatally.[83] The battle was a Mdewakanton victory for the damage done to the town and the procurement of livestock and loot.[83]

At Paynesville, Sauk City, and Maine Prairie the troops surveying the aftermath were certain the vandalism was not done by native hands. They were certain that there were "white" opportunists raiding abandoned properties.[84]

Little Falls

[edit]According to the obituary of the Chippewa war Chief Mou-zoo-mau-nee, the people of Little Falls asked for Chippewa protection. The town was 15 miles downriver from Fort Ripley. The Chief sent 150 warriors.[85] The woman of the town prepared a welcome meal and the men smoked the peace pipe with the Ojibwa.

On 15 September Major General Pope arrived in Minnesota and took command of the Department of the Northwest. He was not a stranger to Minnesota, having been posted to a land survey of the Red River Trail from St. Paul to Fort Gerry in 1849.[86] He quickly issued a reward for Chief Little Crow dead or alive.[87] He also stated that is if one Winnebago had assisted the Sioux it would be used as grounds for their removal.[87]: p.2

Battle of Wood Lake

[edit]The battle, on September 23, was a victory for Col. Sibley that ended most of the hostilities for 1862. Under the cover of darkness the night before the Mdewakanton force moved into position . The next morning a lapse in military discipline inadvertently exposed the ambush positions. Once the element of surprise was lost the Mdewakanton were at a military disadvantage bring outnumbered. The Battle lasted about two hours with Little Crow's force withdrawing in disorder.[88] Chief Mankato was killed.[11]: p.62 Chief Big Eagle later stated that many warriors had been mis-positioned to be involved in the combat.[81] Col. Sibley chose not to pursue the Santee Sioux for lack of cavalry to do it effectively.[11]: p.64 Sibley ordered the burial of the Mdewakamton dead.[11]: p.63 their exact losses are unknown. The USV lost seven with 34 wounded.[88]

Attacks at Breckenridge, Grahams Point and Fort Abercrombie

[edit]

War came first to the Ottertail land office at the Ottertail old crossing where the station house and stables were burnt. Then the Chippewa Village at Pine Lake, next Old Crossing on the Red Lake River, then Breckenridge Station and Graham's Point, the Red River Trail crossing near to Fort Abercrombie.(one of the two places the upper Red could be forded)[89] Graham's point was 50 miles due west of where the Chippewa were attacked near Otter Tail. All 13 buildings at the crossing were torched.[89] When the war party arrived at Breckenridge it had mostly evacuated. Three men and a family remained. A woman was wounded, the men and a boy were killed and a youth was taken prisoner. Abercrombie, like Fort Ridgely had no palisade initially. It was two miles beyond the Red river. Word of the uprising at the lower Agency arrived on August 23. Capt. Van der Hoeck, Abercrombie's commander, was preparing to escort the treaty party to the signing. Those plans were immediately canceled and he sent orders for the detachment at Georgetown to return promptly. On August 31st all the horses, mules, and cattle were raided from Abercrombie by the Santee Sioux. Pierre Bottineau was there returning from the west. Indian Commissioner Dole and his treaty party had remained because of the hostilities.[90] On September 3rd the fort was attacked at day break.[90] That engagement was broke by the arrival of the Northern Militia and G Company 9th Minnesota with it's Chippewa contingent.[91][92] After that relief force joined the garrison the Sisseton force returned. When night fell Bottineau slipped out of the fort , through the Sioux lines to travel 80 miles to Sauk Center for reinforcements.[90] Newspapers in the south assumed Abercrombie had fallen. Captain Van der Hoeck, sent a request to Gov. Ramsey for supplies and reinforcements. If any response was sent, the fort never received it. Annuity goods and 20 beef cattle intended for the Red Lake Band of Chippewa had been brought to the fort for safe keeping on August 24.[93] Amongst those goods were 54 double barrel shotguns. They were appropriated for the civilian militia company. It was formed from refugees at the fort.[94][95] In desperation of assistance, Capt. Van der Hoeck turned to the Chippewa at La Grand Fourche. Pierre Bottineau happened to be there and reported 60 warriors wanted to engage the Santee Sioux immediately. After a day of prolonged discussion the request was denied by the Chiefs.[96] The garrison felt the fort's three howitzers were instrumental to the Fort's not being over run. The defenders acknowledged the bravery the Sioux exhibited assaulting under canon fire.[97] Afterwards, defensive breastworks of soil and timbers were constructed. Blockhouses were added later. A 500 man militia force broke the second siege on September 23.[98] Sources place both Inkpaduta and Little Crow there in September.[99]: p.44

A soldiers letter later described the remains of one defender as mutilated in the same manner as the Redwood ferryman at the Lower Sioux Agency.[100]

Also later, fort defenders and citizens felt Capt. T. D. Smith (post Quartermaster) was owed recognition for his leadership and saving their lives.[101] In one letter the fort commander, Van der Hoeck, was labeled a coward.[100] Of his own volition, he turned command over to a State militia commander. The troops and civilians blamed Van der Hoeck for the two deaths. A letter describes one of the dead, (Joseph Comptois, G Co. 9th Minn), as "one of the bravest citizens, a soldier from the redskins".Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). [102]

Surrender at Red Iron's village, release of the hostages and moves: to the Lower Agency, Fort Snelling, and Mankato

[edit]

On September 26, Sibley's force arrived at Chief Red Iron's peace village where, approximately 1,900 of the Mdewakanton force would eventually surrender,[103] (1,658 were non-combatants)[16]: p.233 At the same time, 269 prisoners the Mdewakanton had taken were released.[99] The captives were mostly women: 162 bi-racial Dacotah females, 107 Caucasian females, plus a few children and men.[104]

Other prisoners were released elsewhere. Yankton Chief Struck-by-the-Ree offered to trade horses for the captives taken at Lake Shetek, 2 women and 6 children, but was turned down by Chiefs White Lodge and Old pawn. The Yankton Chief reminded them who's land they were on and they headed north. One hundred miles north of Fort Pierre a fur trader ran into them and offered to trade goods for the captives. The Sisseton refused saying they would only trade for horses. He continued to Fort Pierre with that information. There a band of Two Kettle Lakota, self named the Strong Hearts, decided to secure their release.[105] They were lead by Chief Four Bears.[106] The band caught up with the Sisseton at the mouth of the Grand river over 200 miles from Fort Pierre.[106] Four Bears offered four horses for the release of the captives.[106] He was scoffed at. The Lakota replied either take the horses or fight.[107] [108] Once they had secured the captives release they made them members of the Lakota.[106] At that point Julia Wright was taken as a wife by one of Four Bear's sons.[106] The Lakota returned the captives to Fort Pierre only to be imprisoned for their effort. Some died awaiting a determination that said they would be rewarded for their actions. Afterwards Julia Wight gave birth to a biracial baby. Mr. Wright abandoned her with the baby. Mrs. Wright left Minnesota and disappeared. In the north, near Pembina, a priest secured the release of boys held by Little Crow.

The surrender at Red Iron's village was not a formal peace agreement or truce. Col. Sibley's decree was that the Santee "surrender at discretion" and release all prisoners.[109] Sixteen of those released were detained as witnesses for the trials.[110]: p.1 That same day the Minnesota legislature proposed strengthening the defensive line of military installations.[111] More of the Santee Dacotah made their way to Camp Release motivated by Sibley's promise to punish only those who had murdered settlers.[16]: p.187 Sibley's troops checked all those surrendering for any that may have been involved in the crimes. It was determined that there were 16 suspects.

On September 28, just days after the surrender, Pope wrote Sibley that; "it is my purpose to utterly exterminate the Sioux...even if it requires a campaign lasting the whole of next year".[99]: p.43 He further wrote: "no treaty must be made with the Sioux...".[99]: p.43 Gen. Pope wrote his superior, Maj. Gen. Halleck the first week of October that the undistributed annuity money would be used to feed the interned Santee Dacotah.[112]

On 18 October it was reported that the Lower Sioux prisoners were returned to the lower Agency so they could harvest their crops.[110][113] They made the relocation from the Upper to lower Agency by foot. The St. Paul Daily termed their entire movement to Fort Snelling a march.[114] At that time Little Crow and a group of 200 fled into Dakota Territory and Rupert's Land.

General Pope ignored Sibley's promise when he ordered all combatants be tried for murder. That changed the status of many men who had surrendered thinking that they were becoming prisoners of war not prisoners for crimes. Little Crow references this as a deception when he spoke with the HBC Governor at Fort Gerry. On his trek there Little Crow's band is displayed the HBC colors likely taken from the HBC post at Lake Traverse.

All those that were tried were moved to the Mankato for the executions of the convicted. It was observed that while there they were "great letter writers" sending between 100-200 letters a week to their families.[115]

At the same time the 1,658 detained non-combatants were moved by wagon to Pike Island at Fort Snelling.[103] B Company 5th Minnesota was relieved at Fort Ridgely and ordered to provide security for the movement. There were several reasons for the move. One was the time of year and survival of the oncoming winter. Another survival concern was protection from the hatred and animosity of the settler's. Another survival issue was they had no money to buy provisions as the annuities had not been distributed. Another survival issue was that the family providers were either in custody or gone, leaving the woman and children in a precarious position. Moving the detainees made the logistics of their oversight easier in not having to assign troops to their protection as well as not having to transport provisions to the frontier in the winter for their sustenance. In Henderson, Minnesota the wagon column was attacked with rocks and scalding water that injured and scarred some in the wagons.[116] One Dacotah mother had her infant severely injured resulting in the babie's death.[116] Shortly after reaching Fort Snelling one of the woman was raped while another was "accidentally" shot illustrating what may have happened on the frontier for all of them.[117] That caused the erection of a palisade around the encampment for safety. After the relocation many Santee changed their minds and slipped away unnoticed.[118] In August 1863 80 Santee were found and taken to Fort Snelling while another 60 were taken to Fort Ridgely.[118] It became a site of public gawking. Winter 1862-3 the hygiene and sanitation conditions were recorded as bad.[119][120] Measles and cholera swept the camp killing between 102 to 300 depending upon source.[103] The "white" refugee camps had public health] issues also.

- B, C, and D Companies 5th Minnesota were all ordered to report to Fort Snelling in November-December 1862 to rejoin the regiment in the south.

In 1863 a prisoner escaped the Santee encampment at Devil's Lake DT. He reported that there were still four girls and two boys being held.[121]

Loyal Mdewakanton and friendly Dacotah

[edit]

During the 1862 attacks at both Agencies "friendly Dacotah" warned settlers or gave them protection.[122]: p.136–8 Some made exceptions for who they killed.[13]: p.305 The Reverend Samuel Hinman reported that Little Crow himself allowed the Reverend and his assistant to flee.[122] A store clerk, reported a warrior saved his life.[123] Some on the warpath exercised restraint when reminded that killing a bi-racial Dacotah would risk retribution from the victims' "full-blood" kinsmen.[13]: p.306 The number of captives became an issue. Some argued that they should be released, while Little Crow insisted that they were valuable to the war effort and should be detained.[122]: p.140–1 Anpeetu-Tokeca (Otherday), a Mdewakaton, is credited with saving 62 settlers. Sisseton Chief Standing Buffalo threatened Little Crow with war if he came to the upper reservation. Standing Buffalo was very displeased that Little Crow had not been consulted him about going to war. He told Little Crow his actions caused great problems the Sisseton. At one point the warriors lodge encircled his camp for not joining the war, but did not end in bloodshed.

In December 32 loyal Dacotah became scouts for Sibley.[9] When the war ended they would total 350 with their families.[99] The Minnesota Valley Historical Society erected a 50' monument to six Loyal Dacotah.[124]

Also in December a band of Two Kettle Lakota rescued the Lake Shetek captives 100 miles north of Fort Pierre on the Missouri river.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

The Two Kettle band was considered "Friendly" for their service as scouts, messengers, and taking scalps during the war.[125]

In 1865-6 Captain Kellogg, Commander of Fort Ridgley, formed three settlements of friendly Sioux before the Lake Traverse Reservation was created. The first was directly west of Fort Ridgely at Lake Hendricks on the Minnesota-Dakota Territory border. The other two were southeast of Lake Hendricks at Lake Titaukhe, and Lake Thompson.[126]

Yankton Chief Strike-the-Ree was loyal to Government. His gravestone says he was the most faithful Sioux friend the "whites" had.[127] During the trials members of Sleepy Eye's band and White Lodge's encamped with "white" captives on his land. He offered to trade a horse for the release of each prisoner and was scorned at by his visitors. He reminded his Sissiton visitors that his offer was one they could not refuse.[99]: p.47 They did and moved north out of his land.

Trials

[edit]Col. Sibley felt that actions of the Mdewakanton force were violations of the Rules of War and that they needed to be addressed immediately. The Rules of war fall under international law, not military law or civil law. However, by the existing standards of the time it is surprising that trials were held at all. It was common practice to summarily execute native Americans and there was no precedent for any having ever been tried in U.S. history. The USV remained in a State of war that was put on pause for the trials. Gen. Pope wanted more engagements, however Sibley informed him that the campaign had ended for the season largely due to drought conditions on the frontier.[99]: 44

In less than six weeks, a military commission, composed of Minnesota USV officers sentenced 303 Mdewakanton to death. President Abraham Lincoln reviewed the convictions granting the largest Executive clemency order of any President, commuting 263 executions.[11]: 72 He also approved death sentences for 39 for the largest mass hanging in U.S. history at Mankato, Minnesota on December 26, 1862. One man received a late commutation. The United States Congress abolished the Santee Sioux and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) reservations in Minnesota and declared their treaties null and void. In May 1863, the Mdewakanton interned at Fort Snelling were expelled from Minnesota as were the Ho-chunck from their reservation by Mankato. They embarked riverboats and taken to Crow Creek Reservation in Dakota territory. The Ho-Chunk later moved to Nebraska.[128]

How Sibley was aware of Military Commissions is not known. It has been speculated that Lincoln's directive authorizing the use of Military Commissions for rebel insurgents a few days earlier was the source.[129]

Col. Sibley had dealt with the Santee Sioux for years and believed they would see him as weak if he did not respond to all the deaths. His having to respond this way hardened his view toward them.[20]: p.39 The detained were primarily Mdewakanton, but some were allies from other tribes as well as bi-racial Dacotah. Col. Sibley initially intended to "summarily try" 16-20 warriors (according to his letters to his wife) for the alleged crimes and outrages the Commission had heard of or personally seen.[130].[20]: p.56 Sibley himself questioned whether he had the authority to create a Commission, but he felt the Mdewakaton's actions necessitated its formation.[131] While forming the Commission Sibley submitted a request on 27 September, 1862 to Gen. Pope and Gov. Ramsey to be relieved by a regular U.S. Army replacement. Having had no officer training he felt the situation would be better served by a professional. Instead he was promoted to Brig. General. He wanted to only try those 16-20 they thought had committed violations of the Rules of War. Instead Gen. Pope ordered all those involved in combat be included, increasing the number to 398.[76]

USV Military Commission

[edit]The purpose of the USA Military Commission was to review the military conduct of Mdewakanton combatants against civilian noncombatants until Gen. Pope intervened demanding regular combat be included. A Military Commission by definition is not comparable to either a military or civilian court. Having an attorney is not a "right" it is a "privilege".[132]

- Military tribunals were born out of necessity. Operating outside the realm of conventional court martials and criminal, and civil courts, they are unique proceedings in which enemy forces are tried during times of war or rebellion. Military commissions are a form of military tribunal, though the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. Tribunals only try members of enemy armies, not civilians who have allegedly broken the law (though sometimes civilians accused of being combatants are tried in a tribunal). Military officers serve as jurors, act as judges, and impose sentences."[133]

- Major General Henry W. Halleck, military law authority wrote in 1862: "Congress has recognized the lawfulness of these tribunals (commissions), and, in a measure regulated their proceedings, but it has not defined or limited their jurisdiction..."[134][20]: p.150

- That year General Halleck also wrote: "Many classes of people cannot be arraigned before (a Military court martial)... and many crimes committed ... cannot be tried under the "Articles of War." Military commissions must be resorted to for such cases and these commissions should be ordered by the same authority..."[134]

- Article 56 of the Articles of War: "Whosoever shall relieve the enemy with money, victuals, or ammunition, or shall knowingly harbor or protect an enemy shall suffer death, or such other punishment as shall be ordered by the sentence of a court martial."

The Commission selected was USV that had volunteered to fight the south. Only Col. Crooks had previous military service with any study of Military law. He had attended West Point.[135] Col. Sibley had two years of law studies, his father was a judge. He had also served as a Justice of Peace. Even-so, he made several inquiries as to the scope and authority of the commission. Major Bradley was a civil lawyer by training and Isaac Heard had been a civil prosecutor so the commission had some legal background.[20]: p.70 Despite this, many legalities were not observed: impartiality, no discovery or cross examination or defense witnesses.[136][26] Gen. Pope stated that anyone with any complicity to the crimes should be hung.[130] Isaac Heard, the court recorder, referenced complicity, but it was not listed on the stenographed charge sheets adopted to speed the trial process. Generalized charges of "participation in murders, rape, robbery, and outrages" were listed with those not applicable struck at trial.[20]: p.78 No one was charged with aiding and abetting or horse stealing. Common law principles were not applied, with no-one charged for being accessories. "Common law separates accessories to crime into four categories. A principal in the first degree actually committed the crime. A principal in the second degree: was present at the scene of the crime and assisted in its commission. An accessory before the fact: was not present at the scene of the crime, but helped prepare for its commission. An accessory after the fact: helped a party to a crime prepare for its commission by providing comfort, aid, and assistance in escaping or avoiding arrest and prosecution or conviction."[137] Child endangerment as a legality did not exist. One of the functions of the Judge Advocate is to represent the accused before a Military Commission, which was Captain Rollin Olin. Under Military Law his failure to preform this function did not invalidate the trials.[20]: p.74 The charges before them were not for either a military or civilian, they were for a War Crimes Tribunal and the Hague did not exist. Out of the 393 cases 69 were dismissed, 18 were given prison and 303 got the death sentence. Had it been left to the citizens of Minnesota they all would have been executed. Gen. Pope was responsible for including all the warriors that Lincoln would commute. His inclusion of the legitimate combatants turned the trials into a farce and the entire history turned into an irreparable stain on Minnesota history even though Lincoln made certain that the men hung were not the men that had 5 minute trials or three page trial transcripts.

International law in 1862 did not extend the Rules of War "uncivilized" peoples. That being said, belligerents go to war with a set of rules. The Dacotah's were kill or be killed and win or withdraw. When it became apparent they would not win many chose to to use the " flag of truce" to "surrender" and become "prisoners of war". The "flag of truce", "surrender" and becoming "prisoners" were not elements of the Dacotah rules of war. Those concepts are components of the European-American War Model. By using the "flag of truce", "surrendering", and becoming "prisoners of war" the Dacotah model of war was forfeit.[20] That made many of their actions crimes under the European-American "Rules of War".[20]: p.146 Claims that indigenous sovereignty exempted the Mdewakanton from being judged by the Military commission are mistaken. Sovereignty has no relevance to a U.S. Military Commission proceeding.[20]: p.148-50

- Minnesota State Senator Wilkinson wrote to President Lincoln: "These Indians are called by some prisoners of war. There was no war about it. It was wholesale robbery, rape, murder. These Indians were not at war with their murdered victims."[18]

- Gen. Pope wrote to Gen. Sibley Sept 28, 1862: "The horrible massacres of women and children and the outrageous abuse of female prisoners, still alive, call for punishment beyond human power to inflict-" The letter indicates that the authorities did not view the hostilities as acts of war.[138]

Accounting for the causalities

[edit]The upraising phase of 1862 had the most causalities. However, military operations continued four more years.[139] The total number of Dacotah casualties was unknown, but historically it has been speculated as being low in comparison.

In 1864 Indian Agent Galbraith compiled a list with 737 killed, of which 77 were Minnesota USV and 29 Minnesota militia.[140][141] That list has primary source status, however the Minnesota Historical Society has no copy of it, which has led to multiple historians making compilations since then. There are claims that Galbraith's numbers were wrong which they were.[142] There were deaths in the following years not on his list. Galbraith's list has multiple victims that were identified only by gender and approximate age. Human remains were found in Southern Minnesota up until World War I, sixty years later, so the actual number will never be known and any number is an approximation at best.[143]

Reverend Williamson speculated at the time that the only way to get an accurate count would be to actually visit the frontier. There were few towns of any size in the war zone limiting the number of directly involved media sources. Sixty years after the event MNHS historian, M.P. Shatterlee, published the first post-war casualty list in The Minneapolis Journal on 10 September 1922.[144] Satterlee's accounting includes no unidentified dead. Satterlee and subsequent historians have arrived at lower causality numbers not having access to Galbraith's records or first hand observations. If there was a missing persons list compiled during the war it also is missing.

Most of Brown County's northern border abutted both Reservations for 150 miles. Having not been platted there is no way to know if or where settlers were living on squatters homesteads. The same is true for the other counties not platted: Ottertail, Douglas, Toombs, Rock, Murray, Redwood, Cottonwood, Pipestone, Noble and Jackson. Accounting for the dead in the counties north of the Minnesota River was easier as those counties had been platted thus providing names to registered homesteads, though Renville, Pierce and Sterns counties were only partially platted. Census records covering the period from Statehood in 1858 until the uprising in 1862 do not provide a good record of the existing population.[145] It was speculated there were many dead not accounted for and would never be because of the prairie fires.[146] Postwar, human remains continued to be found by farmers across southern Minnesota until WWI.[147][148]

August 24 Hq. at St. Peters reported three unidentified dead brought in to be be buried, elderly male and 2 females..[149]: p.3

On August 26 the St. Cloud mayor sent a letter to Gov. Ramsey reporting that a group he had sent to Painesville returned stating they had seen over 200 dead.[150]

28 August the mixed race Chippewa runner from the Big Stone Lake trading post reported eight dead there, three Frenchmen and five Germans. He was detained at St. Cloud.[151]

In Jackson County a massacre of 54 was reported at Springfield.[152]

On September 5 1862 the Pioneer Press published a list of dead totaling 382 just two weeks into the war frontpage.[149] That same issue cited a St. Cloud letter identifying a stage driver killed as well as a letter from Fort Abercrombie stating two stage drivers from Breckinridge were missing.[149]: p.3 On September 21 Militia Cavalry found a decomposing body at Evansville. [153]

September 6 nine bodies were reported found eight miles from New Ulm, two decapitated, one disemboweled on.[154]

On September 21 Rev. Williamson's opinion was published that the only way to get an accurate accounting of the dead was to actually go to the frontier.[155] On September 27 the Reverend reported in the Mankato Semi-Weekly Record a total of 90 dead in Brown County.[70] A month later on October 25 the Semi-Weekly reported Brown County had lost 343.[156] Other papers reprinted the same figure.[157] [158]

26 September the bodies of two men were buried 12 miles north of Old Crossing on the Red lake River.[93]

On 1 October 9 bodies were reported found and buried in Jackson County by cavalry out of Des Moines Iowa. [159] The dead at Breckenridge were identified on October 3.[160] In that same issue more dead were listed for Meeker and McLeod Counties.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). The paper also reported the remains found were so decomposed that belongings were needed to make identifications. At Lake Shetek identity's couldn't be made, they were guessed based upon body size and gender. It was felt that with the ongoing prairie fires some remains would be lost. The 25th Wisconsin buried the dead at Lake Shetek. They reported nine skeletons found with some burnt.[161]

A Mr. Van Eaton's remains were reported found burnt in December.[162] Also in December 1862 two more bodies found[163]

8 May 1863 18 bodies of men, women, and children were found in a ravine three miles from Camp Pope by a scouting party[164]

8 May 1863 Gardner Frost, an experienced trapper, reported missing in Cottonwood County near other reported murders by a fellow trapper he had been working with. His scalp was identified at a campsite found on the Watonwan River.[164]

8 May 1863 The body of an unidentified man was reported found on the Cottonwood River.[164]

8 May 1863 Three men of the 8th Minn. and a cattle driver named Foote were reported killed near Old Crossing[164]

Partial List of soldiers and others who died at Fort Abercrombie,[165]

Minnesota 1860 census [1]

In 2010 Historian Mary Wingerd published that civilian deaths totaled 358.[166]

In 2012 Historian Curtis Dahlin published a death tally of 594 Civilian, 97 Military and Militia, 24 probable, 45 unidentified Victims for the Uprising. [167]

The Mdewakanton force causalities were unknown and remain that way. It is believed their combat losses were low in comparison in 1862. However, General Sully attacked Sioux encampments of women and children in the following years. There has been no accounting for the casualties inflected by those actions. After those attacks he had all the food stores of the Sioux destroyed leaving them destitute for the winter. This would have resulted in casualties that are not accounted for in the war records.

The Outrages, Atrocities, or War Crimes

[edit]The accounts of the killings is a toxic subject.[20]: p. 228 The historic narrative lacks balance for the actions commited by the Government on the opposing side. At the time there were miltiple newspaper accounts of mutilation, dismemberment, decapitations and scalping. It was published that it was felt these actions were the work of smaller bands, not all of the Santee Sioux.[168] These actions were part of indigenous warfare. It was believed that these actions kept the dead from having peace in the afterlife and would cause the spirit to wander forever. The dead at Custer's Last Stand exhibited all of the same depredations.[169] The Mdewakanton warriors lodge made the removal of "whites" from the Minnesota River Valley their mission. The hostilities of the first week resulted in 23 Counties being completely depopulated. Wikipedia describes the removal of an ethnic group from where they are living as ethnic cleansing. When the hostilities ended that is what happened to the four tribes of Santee Sioux. Verifiable first hand accounts provide sufficient evidence that War crimes were committed.[20] Very early in the war Americans advertised in newspapers bounties for the taking of Sioux scalps.[170]

In 1862 the term "Massacre" was used to describe multiple incidents where Mdewakanton belligerents killed unarmed civilians. Wikipedia states that there is not a consensus even today for the definition of Massacre. However, Wikipedia describes War crimes as the killing of unarmed men, woman, children and infants. The historic record identifies the following Mdewakanton actions as the: Acton Massacre, Lower Sioux Agency Massacre, Beaver Creek Massacre, Manannah Massacre, Belmont Massacre,[171] West Lake Massacre.[172] and the Massacre at Lake Shetek. Of those killed in these engagements over 30% were children.[173]

There were multiple victims that were scalped.[64][174] In Renville County one child had his face blown off.[175] The four children of one settler were kicked to death, children of another family were beaten to death. Their cause of death would be listed as from brutality.[175][176] In the Breckenridge Hotel three men were found with no visible mortal wounds beaten to death.[177] The remains woman and children were found charred at multiple farmsteads.[175] Two pregnant females were disemboweled.[175] One was having twins. A two day old baby was injured beyond aid at the Lower Sioux Agency. Babies that became prisoners with their mothers were killed for crying.[175][178] Many victims died from gunfire, one was shot in the back 8 times.[64] There are multiple accounts of bodies having been mutilated and skulls being crushed.[179] The accounts of crushed skulls were to be expected as the standard side weapon of the Dacotah was the iŋyaŋ iŋjátʾe. Breaking bone was it's sole purpose and Americans called them skull crackers.[180]

The Mdewaketon force took many prisoners, mostly women. The 1862 news media hyped a narrative that they had been taken for non-consensual sex.[53] The differentiation between fact and fiction on female abuse remains in dispute.[181] One source states nearly all of the females were forced into relationships. [16]: p.191 George Spencer's firsthand account states nearly all the female captives were raped.[182] The native narrative was they wanted wife's and that is how Dacotah warfare worked. There are three documented cases of female captives being "adopted" and protected by "friendly" Mdewakanton.[181] Rape in 1862 was not a topic for polite conversation, meaning that there were women present. Only two women endured the humiliation of appearing before the tribunal to identify their assailants, but others are documented, with multiple gang rapes.[143] One 10 year old girl was abused to death.*[183] Another gang rape-murder was recorded at Norwegian Grove.[184] In one case the woman bore a child and was abandoned by her husband.[20]: p.225 In another case the woman miscarried and suffered a mental breakdown.[20]: p.225 The record identifies two females that were decapitated one whose head was not recovered.[143][175] At the Lower Sioux Agency two men were decapitated with one head found scalped.[185] An early fatality was the ferryman at Redwood Ferry. He was decapitated, disemboweled and dismembered. His hands and feet were cut off and shoved into the body cavity.[186] At Green Lake both Andros Lorrenson and Sven Buckland were decapitated.[187]

Settlers, numbering thousands, fled 23 counties leaving everything much of which was pillaged.[188] At the gallows, one of the convicted said to the onlookers: "if a decapitated body was found near New Ulm with the head placed on it" he did it.[189] Theft by combatants is called looting or pillaging and is a War Crime. Isaac Heard, the court recorder, said no one received a death sentence Plunder.[20]: p.160 Plunder is what taken from the Agency warehouses and settler's homesteads. [190] Commission proceedings aside, horse stealing was a hanging offense across the entire American west. At least one prisoner was charged with horse theft, but the charge was dropped because it could not be proven beyond doubt. Lincoln made it clear that combat itself was not a crime. One combatant killing another is killing, it is not murder.

The historic narrative is famous for the accounts of atrocities that happened mostly in the early days of the war. They are a point of contention that is unresolved. The media had a field day publishing the "atrocities" in 1862 and they have since been well researched. A great deal of the historic narrative has been discredited as hype and racism. Crimes that would be labeled atrocities would be inflecting pain before death and rape. The first hand accounts of Laurina Eastlick, Willemina Inefeldt, Justina Kreuger and Emanuel Ryff indicate there is truth to a number of the accusations.[20]: p.169 Some dismiss those incidents using the Dacotah War model saying those actions were not War Crimes, but acceptable Dacotah warfare. Descendants of the survivors of the Mdewakanton attacks claim that is an effort to legitimize the War crimes committed and to blame the victims for their own deaths.[191]

- The over 100 infants and children killed makes the term infanticide applicable to the Mdewakanton actions from the American perspective.[20]: p.163, 170 From the Dacotah perspective it was standard warfare. The differences being a cultural clash of definitions and values that are irreconcilable.[192]

Belligerents do not get to start a conflict with one set of Rules of War and change to another set when things don't go their way. The Mdewakanton used the Euro-American "flag of truce" to "surrender", and become "prisoners of war" making their killings "murders" and the deaths of children war crimes.

In 1862 there were no public social services and in St. Paul, there were 23 widows and 57 children that had lost both parents.[193][194] There were refugee centers at Mankato and St. Peter also. The same lack of social services existed for the Mdewakanton woman on Pike Island and out on the High plains. Appeals for aid were published by the newspapers.[195]

Mass Commutations and Mass Convictions, December 1862

[edit]

Once the trials were completed Sibley sent Pope a letter requesting permission to execute the convicted.[198] The Commission's verdicts were subject to review by the commander in chief, President Abraham Lincoln. Pope wrote, "the Sioux prisoners will be executed unless the President forbids it, which I am sure he will not do."[198] The word Lincoln had received was 800 unarmed Minnesota citizens had been massacred by the Sioux. Historians of differing POVs have cited numbers ranging from the 360 to 800 plus, what ever it is it remains in the hundreds.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). The record indicates that the men executed were not sent to the gallows from 5 minute trials. The citizens of Minnesota were unhappy with his verdicts at the time and today Lincoln is vilified by the media.[27] Plenary power gives the President the authority to review and alter convictions for violation of Federal law only. It is what Lincoln exercised in the 263 cases he commuted. He wanted the trial record to "indicate the more guilty and influential of the culprits" were the ones that were executed. [199] After the hangings Lincoln again reviewed the files of the cases he had commuted and concluded that none of those men would hang. He kept this undisclosed.[200]: p.67 He also kept the Chippewa offers to help in his pocket.

The trials took place in the theater of hostilities. However, neutral ground is not a requirement for USA Military commissions. There were many legalities not observed, lack of impartiality and discovery, no cross examination or defense witnesses.[136][26] The commission failed in legal ethics by not following: legal protocols, administering due process, or inpart impartial justice based upon factual evidence.[20]: p.70 The Commission's neutrality was an issue to both the Army and Lincoln.[135] The first trials are identified as the Sibley phase, took time, Godfrey's took several days.[20]: p.85 Gen. Pope became upset with the time the trials were taking and ordered Sibley to speed them up.[20]: p.85 It was and is today a major criticism of the proceedings as there was no due process. General Pope turned the trials into a farce with his demand for swift verdicts.[20] At Gen. Pope's instruction the majority of cases were summarily reviewed, most very quickly.[135]

Gen. Sibley's authority to organize a Military Commission has been questioned.[135] The day he convened the Commission he had the rank of Colonel and his action was not within his authority. His promotion to Brigadier General the next day made the commission legal. So the trial of the first day could be nominally disputed.[20] It was determined a year later that Sibley's personal bias removed his authority to convene the tribunal according to Article 65.[19]: p.57 That the tribunal was intended to address War crimes not military or civil crimes is not discussed anywhere. Another issue some have raised is the legality of the commission itself. By 1862 Military commissions were an established element of U.S. Army jurisprudence. However, they functioned with different legal authority and less requirements than Army tribunals to produce a more expedient decision. The trials have been identified for having two different phases. The first 18 days were the Sibley Phase during which the Commission arraigned 29 cases. During the 21 days of the Pope Phase that followed the Commission completed 363 cases and any semblance of due process disappeared.[20]: p.85 Part of the reduction in time spent per case was the use of a stereotyped form with the various charges listed which could be struck or added to.[20]: p.85 Lincoln's review dismissed the majority of cases from the Pope Phase. As the convening Officer Sibley was responsible for reviewing the commissions findings. However, he overstepped his authority by returning cases for reconsideration. Despite the violation, the commission changed none of their original decisions.

A complete redo of the trials was not a viable option with the Civil War going on and public sentiment in Minnesota. Today some state Lincoln slaughtered those executed. That the travesty trials of the legitimate combatants made the War crime trials travesties too and that Lincoln should have commuted them all. When done, the tribunal had reviewed 392 cases, convicting 321 of which 303 received the death penalty.[135][69] The condemned were moved to Mankato, the nearest intact population center. The column was attacked by a mob in New Ulm and two prisoners later died from injuries a second attack was thwarted.[201] Gen. Sibley wrote that 15 were seriously injured as were some of his troops.[20]: p.117 The settlers wanted the Dakota War model justice without waiting for that of the European-American model.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). Of the 69 defendants acquitted only eight were released. The other 61 were held in what amounted to protective custody.[20]: p.99

On November 10 1862 President Lincoln was informed by Gen. Pope of the verdicts.Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page). On the other side, Gen. Pope and Senator Morton S. Wilkinson warned Lincoln that Minnesotans opposed any leniency. Gov. Ramsey warned him that, unless all 303 Sioux were executed, "[P]rivate revenge would on all this border take the place of official judgment on these Indians."[202] Lincoln and his staff completed their review in under a month.[16]: p.251 On December 11 1862, Lincoln addressed the Senate regarding his final decision as they had requested on December 5:

"Anxious to not act with so much clemency as to encourage another outbreak on the one hand, nor with so much severity as to be real cruelty on the other, I caused a careful examination of the records of trials to be made, in view of first ordering the execution of such as had been proved guilty of violating females. Contrary to my expectations, only two of this class were found. I then directed a further examination, and a classification of all who were proven to have participated in massacres, as distinguished from participation in battles. This class numbered forty, and included the two convicted of female violation. One of the number is strongly recommended by the commission which tried them for commutation to ten years' imprisonment. I have ordered the other thirty-nine to be executed on Friday, the 19th instant."[203]

The result was the largest "mass clemency" ever granted for 264, while authorizing the largest "mass execution" of 39.[204] There was one additional commutation based upon new information."[19] The Lincoln's clemency resulted in protests from Minnesota, which persisted until the Secretary of the Interior offered Minnesotans "reasonable compensation for the depredations committed." Republicans did not fare as well in Minnesota in the 1864 election. Ramsey told Lincoln that more hangings would have produced a better vote. Lincoln responded he: " could not afford to hang men for votes." Lincoln's review determined thirty nine would be executed for crimes against civilians.[205] As to the men he pardoned, Lincoln instructed that they be held until further orders: "taking care they neither escape, no are subjected to any unlawful violence".[199]

The commission's interrogator and interpreter were : Reverend Stephan R. Riggs (had missionary school and chapel by Upper Sioux Agency and wrote a Dakota dictionary)[184] and Antoine Frenier (Fort Ridgely's biracial-Dacotah interpreter).[206] Today there are claims that Frenier and Rev. Riggs didn't translate the court proceedings to the prisoners. That they failed to communicate the situation and the prisoners did not comprehend or understand that could be executed by the Military tribunal. General Sibley and States witness Godfrey are also identified for speaking Dacotah. Prisoners statements taken by Rev. Riggs were released.[207]

- On December 1st Lincoln suggested to Congress: " I submit for your especial consideration whether our Indian system shall not be remodeled." in his second Annual message to them.[208] He was further quoted as saying "this Indian system shall be reformed".[209]

A 2,000 man security detail was posted for the executions on December 26, 1862 comprised of: Companies D, E, and H of the 9th Minnesota, Companies A, B, F, G, H, and K 10th Minnesota and the 1st Minnesota Cavalry.[212] [213][214] The size of the security was dictated by the numbers of hostile Minnesotans encamped at Mankato and the concern of what they wanted to do to the prisoners not being hanged.[212] It is the largest mass execution in American history as well as the largest act of Executive clemency by a president.

The execution was public. The gallows platform was built as a square with ten nooses per side. It was designed to drop from under the condemned resulting in a simultaneous execution for up to 40. The rope of Cut Nose broke. Despite appearing dead he was hauled back up with a new rope. Once the military surgeons pronounced the men dead, they were buried en masse in an unfrozen sand bar along the Minnesota River. Dr. Sheardown, surgeon of the 10th Minnesota removed skin from the corpse of Cut Nose as a war trophy that eventually ended up in .[215] Despite the guard detail posted, all of the corpses were robbed that night.[212] The prisoners not executed were imprisoned at Mankato the winter of 1862-3. The Commander of the 7th Minnesota sent the executioner's ax and one of the nooses to the Minnesota Historical Society as trophy's from Mankato.[216]

- Body snatching was common in 1862 due to a demand for medical cadavers. Dr.William Mayo of Mayo Clinic fame acquired two of the corpses, one being Marpiya te ajin.[217] In accordance with the U.S. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act the Mayo Clinic returned the skulls the two men to the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council in 1998. In 2000 a tanned piece of Cut Nose's skin was returned from the Grand Rapids Public Museum in Michigan that had been taken by the Dr. Sheardown.[218]

Chippewa offers to fight the Sioux

[edit]

In June Chief Hole in the Day and Little Crow had exchanged letters over a Chippewa having killed a Sioux. Little Crow had told him that the Sioux wanted war.[221] Hole in the Day had his own major grievances with the Government,[221] but they were not enough for him to join the Santee Sioux. Like the other leaders of the Chippewa he offered to fight the Sioux.[221] Also in June, a Sioux-Chippewa skirmish took place near Pembina with losses on both sides. However, one of Chief Red Bear's sons was killed by the Sioux.[225] Days before the uprising, Little Crow sent Hole-in-the-Day a letter informing that he had tried to stop a war party from departing the lower agency that had gone looking for Chippewa. They committed the murders at Acton on 17 August after not finding any Chippewa to fight.[226][227]

In the north stagecoach stations along the Red River Trails were attacked despite being in Chippewa land. When Judge Cooper, Hole-in-the-Day's legal advisor,[228] arrived at Hole in the Day's village, during the first week of the war, he learned the Sioux had attacked the Chippewa at Otter tail lakes.[5] He informed Gov. Ramsey the warriors were dancing with Sioux scalps when he arrived.[5] The friendly upper reservation Dacotah "Other Day" also reported a war party having gone against the Chippewa from just before the Uprising began.[229] On 28 August a paper reported the war party numbered 100 and intended to fight the Red Lakers. [230]

Fort Abercrombie, on the Red River of the North was garrisoned by Company D of the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment. They would be augmented by G Co. 9th Minnesota and the "The Northern Rangers" militia. G Company had a large component of White Earth Chippewa.[231] Crow Wing Americans used alcohol to get the bi-racial Chippewa intoxicated and sign papers as substitutes to fight in the Civil War. Hole-in the Day was furious when he learned of the subterfuge.[228]: p.201 One of those men was killed and buried with military honors before Company G even left St Cloud.[232] They arrived at Fort Abercrombie on 3 September to find the Fort under Sioux attack and went into action to break the siege.[32]: p.53-58 The Company joined the garrison and immediately endured the Sioux siege that followed.