Cave of Altamira

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (May 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

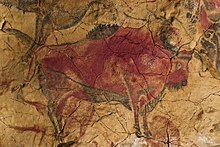

Cueva de Altamira | |

Magdalenian polychrome bison | |

| Location | Santillana del Mar (Cantabria), Spain |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°22′57″N 4°7′13″W / 43.38250°N 4.12028°W |

| Type | Cave painting |

| History | |

| Periods | Aurignacian–Magdalenian |

| Site notes | |

| Discovered | 1868 |

| Official name | Cave of Altamira |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iii |

| Designated | 1985 (9th session) |

| Part of | Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain |

| Reference no. | 310-001 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Buffer zone | 16 ha (0.062 sq mi) |

| Official name | Cueva de Altamira |

| Type | Non-movable |

| Criteria | Monument |

| Designated | 25 April 1924 |

| Reference no. | RI-51-0000266 |

The Cave of Altamira (/ˌæltəˈmɪərə/ AL-tə-MEER-ə; Template:Lang-es [ˈkweβa ðe altaˈmiɾa]) is a cave complex, located near the historic town of Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, Spain. It is renowned for prehistoric cave art featuring charcoal drawings and polychrome paintings of contemporary local fauna and human hands. The earliest paintings were applied during the Upper Paleolithic, around 36,000 years ago.[1] The site was discovered in 1868 by Modesto Cubillas and subsequently studied by Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola.[2]

Aside from the striking quality of its polychromatic art, Altamira's fame stems from the fact that its paintings were the first European cave paintings for which a prehistoric origin was suggested and promoted. Sautuola published his research with the support of Juan de Vilanova y Piera in 1880, to initial public acclaim.

However, the publication of Sanz de Sautuola's research quickly led to a bitter public controversy among experts, some of whom rejected the prehistoric origin of the paintings on the grounds that prehistoric human beings lacked sufficient ability for abstract thought. The controversy continued until 1902, by which time reports of similar findings of prehistoric paintings in the Franco-Cantabrian region had accumulated and the evidence could no longer be rejected.[3]

Altamira is located in the Franco-Cantabrian region and in 1985 was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as a key location of the Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain.[4] The cave can no longer be visited, for conservation reasons, but there are replicas of a section at the site and elsewhere.

Description

The cave is approximately 1,000 m (3,300 ft) long[5] and consists of a series of twisting passages and chambers. The main passage varies from two to six meters in height. The cave was formed through collapses following early karst phenomena in the calcareous rock of Mount Vispieres.

Archaeological excavations in the cave floor found rich deposits of artifacts from the Upper Solutrean (c. 18,500 years ago) and Lower Magdalenian (between c. 16,590 and 14,000 years ago). Both periods belong to the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. In the two millennia between these two occupations, the cave was evidently inhabited only by wild animals.

Human occupants of the site were well-positioned to take advantage of the rich wildlife that grazed in the valleys of the surrounding mountains as well as the marine life available in nearby coastal areas. Around 13,000 years ago a rockfall sealed the cave's entrance, preserving its contents until its eventual discovery, which occurred after a nearby tree fell and disturbed the fallen rocks.

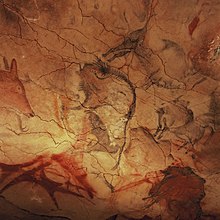

Human occupation was limited to the cave mouth, although paintings were created throughout the length of the cave. The artists used charcoal and ochre or hematite to create the images, often diluting these pigments to produce variations in intensity and creating an impression of chiaroscuro. They also exploited the natural contours of the cave walls to give their subjects a three-dimensional effect. The Polychrome Ceiling is the most impressive feature of the cave, depicting a herd of extinct steppe bison (Bison priscus[6]) in different poses, two horses, a large doe, and possibly a wild boar.

Dated to the Magdalenian occupation, these paintings include abstract shapes in addition to animal subjects. Solutrean paintings include images of horses and goats, as well as handprints that were created when artists placed their hands on the cave wall and blew pigment over them to leave a negative image. Numerous other caves in northern Spain contain Paleolithic art, but none is as complex or well-populated as Altamira.

Discovery, excavation, scepticism

In 1879, following its discovery a decade earlier, amateur archaeologist Marcelino Sanz de Sautuola was led by his eight-year-old daughter María to the cave and realized that the markings on the walls constituted drawings.[7] The cave was excavated by Sautuola and archaeologist Juan Vilanova y Piera from the University of Madrid, resulting in a much acclaimed publication in 1880 which interpreted the paintings as Paleolithic in origin. The French specialists, led by Gabriel de Mortillet and Émile Cartailhac, were particularly adamant in rejecting the hypothesis of Sautuola and Piera, whose findings were loudly ridiculed at the 1880 Prehistorical Congress in Lisbon.

Due to the high artistic quality, and the exceptional state of conservation of the paintings, Sautuola was accused of forgery, as he was unable to answer why there were no soot (smoke) marks on the walls and ceilings of the cave. A fellow countryman maintained that the paintings had been produced by a contemporary artist, on Sautuola's orders. Later, Sautuola found out the artist could have used marrow fat as oil for the lamp, producing much less soot than any other combustibles.

It was not until 1902, when several other findings of prehistoric paintings had served to render the hypothesis of the extreme antiquity of the Altamira paintings less offensive, that the scientific society retracted their opposition to the Spaniards. That year, Cartailhac emphatically admitted his mistake in the famous article, "Mea culpa d'un sceptique", published in the journal L'Anthropologie.[8] Sautuola, having died 14 years earlier, did not live to witness his rehabilitation.

Cartailhac went on to write a pair of books about the cave, assisted by Henri Breuil's hand-drawn reproductions of the paintings. Breuil was both a Catholic priest and a competent draughtsman, whose connection with the cave is discussed in the first chapter of G. K. Chesterton's book, The Everlasting Man.

Further excavation work on the cave was done by Hermilio Alcalde del Río between 1902 and 1904, the German Hugo Obermaier between 1924 and 1925 and finally by Joaquín González Echegaray in 1968.

Dating and periodization

There is no scientific agreement on the dating of the archeological artifacts found in the cave, nor the drawings and paintings, and scientists continue to evaluate the age of the cave art at Altamira.

In 2008, researchers using uranium-thorium dating found that the paintings were completed over a period of up to 20,000 years rather than during a comparatively brief period.[9]

A later study published in 2012 based on data obtained from further uranium-thorium dating research, dated some paintings in several caves in North Spain, including some of the claviform signs in the "Gran sala" of Altamira. The oldest sign found, a "large red claviform-like symbol of Techo de los Polícromos", was dated to 36.16±0.61 ka (corrected), i.e. still well within the Aurignacian. A red dotted outline horse, also in the Techo de los Polícromos chamber, was dated to 22.11±0.13 ka (beginning Solutrean), establishing that the paintings span a period of more than 10,000 years.[1]

Visitors and replicas

During the 1970s and 2000s, the paintings were being damaged by the carbon dioxide and water vapour in the breath of the large number of visitors. Altamira was completely closed to the public in 1977, and reopened to limited access in 1982. Very few visitors were allowed in per day, resulting in a three-year waiting list. After green mould began to appear on some paintings in 2002, the caves were closed to public access.[10]

A replica cave and museum were built nearby and completed in 2001 by Manuel Franquelo and Sven Nebel, reproducing the cave and its art. The replica allows a more comfortable view of the polychrome paintings of the main hall of the cave, as well as a selection of minor works. It also includes some sculptures of human faces that are not visitable in the real cave.[7]

As well as the adjacent National Museum and Research Center of Altamira there are reproductions in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain (Madrid), in the Deutsches Museum in Munich (completed 1964) and in Japan (completed 1993).

During 2010 there were plans to reopen access to the cave towards the end of that year.[11] In December 2010, however, the Spanish Ministry of Culture decided that the cave would remain closed to the public.[12] This decision was based on advice from a group of experts who had found that the conservation conditions inside the cave had become much more stable since the closure.

Cultural impact

Some of the polychrome paintings at Altamira Cave are well known in Spanish popular culture. The logo used by the autonomous government of Cantabria to promote tourism to the region is based on one of the bisons in this cave. Bisonte (Spanish for "bison"), a Spanish cigarette brand of the 20th century, also used a Paleolithic style bison figure along with its logo.

The Spanish comic series Altamiro de la Cueva, created in 1965, is named for the Altamira Cave. The comic series depicts the adventures of a group of prehistoric cavemen, shown as modern people, but dressed in pieces of fur, similarly to the Flintstones.

The song "The Caves of Altamira" appears on the 1976 album The Royal Scam by jazz-rock band Steely Dan, later covered by soul group Perri.

The mid-20th-century modern dinnerware line Primitive, designed by Viktor Schreckengost for the American pottery company Salem China, was based on the bison, deer, and stick figure hunters depicted in the Altamira cave paintings.

The iconic bison image has been used for the cover of the poetry collection Songs for the Devil and Death by Scottish author Hal Duncan.[13]

The protagonist in Satyajit Ray's film Agantuk was inspired by the charging Bison painting to leave his home and study tribal people.

In 2007, the caves were selected as one of the 12 Treasures of Spain, a contest conducted by broadcasters Antena 3 and COPE.[14]

In 2016, British Director Hugh Hudson released the film Altamira (called Finding Altamira outside Spain) about the discovery of the caves, starring Antonio Banderas and with music by Mark Knopfler released on the soundtrack album Altamira.[15]

See also

- 7742 Altamira, asteroid named after the cave

- Art of the Upper Paleolithic

- Chauvet Cave

- Caves in Cantabria

- List of Stone Age art

- Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain

References

- ^ a b A. W. G. Pike et al., "U-Series Dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 Caves in Spain", Science 336, 1409 (2012), doi:10.1126/science.1219957. "We present uranium-series disequilibrium dates of calcite deposits overlying or underlying art found in 11 caves, including the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage sites of Altamira, El Castillo, and Tito Bustillo, Spain. The results demonstrate that the tradition of decorating caves extends back at least to the Early Aurignacian period, with minimum ages of 40.8 thousand years for a red disk, 37.3 thousand years for a hand stencil, and 35.6 thousand years for a claviform-like symbol. These minimum ages reveal either that cave art was a part of the cultural repertoire of the first anatomically modern humans in Europe or that perhaps Neandertals also engaged in painting caves." Table 1: Ages are corrected for detritus by using an assumed 232Th/238U activity of 1.250±0.625 and 230Th/238U and 234U/238U at equilibrium.

- ^ "The discovery of Altamira". Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Busch, Simon (February 28, 2014). "Prehistoric paintings in Spain's Altamira cave revealed to a lucky few". Cable News Network. Retrieved December 19, 2016.

- ^ "Cave of Altamira and Paleolithic Cave Art of Northern Spain". unesco. Retrieved December 30, 2016.

- ^ Ian Chilvers, ed. (2004). "Altamira". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art (3rd ed.). [Oxford]: Oxford University Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-19-860476-9.

- ^ Verkaar, E. L. C. (19 March 2004). "Maternal and Paternal Lineages in Cross-Breeding Bovine Species. Has Wisent a Hybrid Origin?". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 21 (7): 1165–1170. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh064. PMID 14739241.

- ^ a b Travel Advisory; A Modern Copy Of Ancient Masters, The New York Times, 4 November 2001

- ^ Cartailhac, Émile (1902). "Les Cavernes ornées de dessins, la grotte d'Altamira, Espagne, "Mea culpa" d'un sceptique"". L'Anthropologie (XIII): 348–354.

- ^ Gray, Richard (5 October 2008). "Prehistoric cave paintings took up to 20,000 years to complete". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ "Altamira cave paintings to be opened to the public once again". TheGuardian.com. 26 February 2014.

- ^ "Spain to reopen access to prehistoric cave paintings < Spanish news | Expatica Spain". Archived from the original on 2011-09-17. Retrieved 2010-06-09.

- ^ Visita la Cueva de Altamira

- ^ Songs for the Devil and Death | Circle Six Archived 2012-08-02 at archive.today

- ^ Gómez, Javier (1 January 2008). "Los 12 Tesoros de España, resultados definitivos y ganadores". Sobre Turismo (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Altamira". Film Music Site. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Curtis, Gregory. The Cave Painters: Probing the Mysteries of the World's First Artists. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-4000-4348-4)).

- Guthrie, R. Dale. The Nature of Prehistoric Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 0-226-31126-0).

- McNeill, William H. "Secrets of the Cave Paintings", The New York Review of Books, Vol. 53, No. 16, October 19, 2006.

- Pike, A. W. G.; Hoffmann, D. L.; Garcia-Diez, M.; Pettitt, P. B.; Alcolea, J.; De Balbin, R.; Gonzalez-Sainz, C.; de las Heras, C.; Lasheras, J. A.; Montes, R.; Zilhao, J. (14 June 2012). "U-Series Dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 Caves in Spain". Science. 336 (6087): 1409–1413. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1409P. doi:10.1126/science.1219957. PMID 22700921. S2CID 7807664.

- Sustainable tourism and social value at World Heritage Sites: Towards a conservation plan for Altamira, Spain. Annals of Tourism Research. Eva Parga-Dans & Pablo Alonso González.

- The Altamira controversy: Assessing the economic impact of a world heritage site for planning and tourism management. Journal of Cultural Heritage. Eva Parga-Dans & Pablo Alonso González.

- The social value of heritage: Balancing the promotion-preservation relationship in the Altamira World Heritage Site, Spain. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management. Eva Parga-Dans, Pablo Alonso González & Raimundo Otero-Enríquez.

External links

- Altamira Cave National Museum (in Spanish and English)

- The Spanish Cave of Altamira opens – with politics Bradshaw Foundation Article

- "Les peintures préhistoriques de la grotte d’Altamira", Cartailhac and Breuil founding article (1903), online and analyzed on BibNum [click 'à télécharger' for English version]

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016)