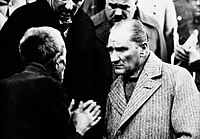

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk | |

|---|---|

| File:Ataturk23.jpg | |

| 1st President of Turkey | |

| In office October 29, 1923 – November 10, 1938 | |

| Succeeded by | İsmet İnönü |

| 1st Prime Minister of Turkey | |

| In office 3 May 1920 – 24 January 1921 | |

| Succeeded by | Fevzi Çakmak |

| 1st Speaker of the Parliament | |

| In office 1920–1923 | |

| Succeeded by | Ali Fethi Okyar |

| 1st Leader of the R.P.P. | |

| In office 1921–1938 | |

| Succeeded by | Ali Fethi Okyar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 350px May 19, 1881 (day and month are adopted) |

| Died | November 10, 1938 |

| Resting place | 350px |

| Nationality | Turkish |

| Political party | Republican People's Party |

| Spouse | Lâtife Uşaklıgil (1923–25) |

| Parent |

|

| Signature | File:SignitureofMKAtaturk.png |

Template:Infobox Mustafa Kemal Ataturk extension Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881 – November 10, 1938) was an army officer, revolutionary statesman, the founder of the Republic of Turkey and its first President.

Mustafa Kemal established himself as a successful and extremely capable military commander while serving as a division commander in the Battle of Gallipoli. Afterwards he had fought with distinction on the eastern Anatolian and Palestinian fronts, making a name for himself during World War I. [1] Following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire at the hands of the Allies, and the subsequent plans for its partition, Mustafa Kemal led the Turkish national movement in what would become the Turkish War of Independence. Having established a provisional government in Ankara, he defeated the forces sent by the Entente powers. His successful military campaigns led to the liberation of the country and to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey.

Mustafa Kemal then embarked on a major programme of reforms, in the political, economic and cultural aspects of life in Turkey with the perspectives defined in the Kemalist ideology, which sought to create a modern, democratic and secular nation-state.

Name

Born as Mustafa (meaning The Chosen One), he acquired Kemal (meaning Perfection) as a second name during his elementary school years. He was known as Mustafa Kemal, or commonly Kemal Pasha, until his resignation from the Ottoman Army. During the War of Independence, the Turkish National Assembly assigned him the title Gazi, hence "Gazi Mustafa Kemal". With the passage of the surname law on November 21, 1934, he took the surname Öz (meaning True/Real or Core/Essence), but on November 24, 1934, the Turkish National Assembly bestowed on him the surname Atatürk (meaning Father of the Turks), hence Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.[2] He is revered by the people of Turkey as the Father of the Nation.

Early life

Atatürk was born in 1881 in the Ottoman city of Selânik (modern-day Thessaloniki, Greece) as the son of a minor official who became a timber merchant. In accordance with the prevalent Turkish custom of that period, he was given a single name, Mustafa. His father, Ali Rıza Efendi, was a customs officer who died when Mustafa was only 7 years old, leaving behind his widowed wife Zübeyde Hanım to raise the young Mustafa.

When Atatürk was 12 years old, he went to the military schools of Selânik and Manastır (present-day Bitola, Republic of Macedonia), both of which saw discontent and revolts towards the Ottoman administration. Mustafa went on to study at the military secondary school in Selânik, where the additional name Kemal (meaning Perfection or Maturity, not an uncommon name) was given to him by his mathematics teacher in recognition of his academic excellence.[3] Mustafa Kemal enrolled into the Ottoman Army Academy at Manastır in 1895. He graduated as a lieutenant in 1905 and was assigned to the 5th Army based in Damascus. There he soon joined a small secret revolutionary society of reformist officers called Vatan ve Hürriyet (Motherland and Liberty), becoming an active opponent of the Ottoman autocratic regime of Abdülhamid II. In 1907, Kemal was promoted to the rank of captain and was assigned to the 3rd Army in Manastır, it was during this period he joined the Committee of Union and Progress, commonly known as the Young Turks.

1908 Revolution and its aftermath

The Young Turks seized power from the Sultan Abdülhamid II in 1908, and Mustafa Kemal became a senior military figure. Having been an early member of the CUP, Kemal was one of the activist officers who took part in the revolution of 1908. However, in later years he became known for his opposition to, and frequent criticism of, the policies pursued by the leadership of the CUP. Particularly, his relations with Enver Pasha had been tense. As a result, Mustafa Kemal was left outside the centre of power once Enver had emerged as the foremost military leader after 1913.[4]

In 1910, Atatürk took part in the Picardie army maneuvers in France, and in 1911, served at the Ministry of War (Harbiye Nezareti) in Istanbul. Later in 1911, he was posted to the province of Trablusgarp (present-day Libya) to fight against the Italian invasion. Following the successful defense of Tobruk on December 22, 1911, he was appointed the commander of Derne on March 6, 1912.

He returned to Istanbul following the outbreak of the Balkan Wars in October 1912. During the First Balkan War, Kemal fought against the Bulgarian army at Gallipoli and Bolayır on the coast of Thrace, and played a crucial role in the recapture of Edirne and Didymoteicho during the Second Balkan War. In 1913, he was appointed military attaché to Sofia, partly because Enver Pasha saw him as a potential rival and sought to remove him from the capital with its political intrigues. By March 1914, whilst serving in Sofia, Kemal was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Military career in World War I

While in Sofia, Mustafa Kemal became a vocal critic of Turkey's entry into the war on Germany's side. On July 16, 1914, he sent an official dispatchment from Sofia to the Ministry of War in Istanbul, urging a policy of Turkish neutrality in the event of war, with a view to possible later intervention against the Central Powers.[5] However, the Minister of War, Enver Pasha, favoured an alliance with Germany, leading to a secret alliance treaty being signed between the two governments. The Ottoman Empire eventually entered the First World War on Germany's side.

Battle of Gallipoli, 1915-1916

The German Marshal Otto Liman von Sanders was assigned to defend the Dardanelles in command of the 5th Army. Mustafa Kemal was given the task of organizing and commanding the 19th Division attached to the 5th Army. On 8 January 1915, the British War Council launched an operation "to bombard and take the Gallipoli peninsula with Istanbul as its objective".

The British naval attacks failed to break through the Dardanelles Strait and the British decided to support their fleet with a landing operation. The land campaign took place between April 25, 1915, and January 9, 1916. With his division stationed in Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal found himself at the centre of the Allies' attempts to force their way into the peninsula.

On 25 April 1915, the Anzacs were to move inland after landing their troops at Anzac Cove, but soon they met with a Turkish counter attack, commanded by Mustafa Kemal. Mustafa Kemal encountered the enemy forces on the hills, held them, and retook the high ground. Largely owing to him and his command, the Australian and New Zealand (ANZAC) forces were contained, and the landing force failed to reach its objectives.[6]

Before the encounter between the two forces, Mustafa Kemal told his troops:

"I don’t order you to fight, I order you to die. In the time it takes us to die, other troops and commanders can come and take our places."[6]

By nightfall the Anzacs had suffered 2,000 casualties and were fighting to stay on the beach.[7] For the following two weeks the Allies remained on the beaches, losing one third of their force.[8] Mustafa Kemal, by holding off the Allied forces at Conkbayırı (Chunuk Bair), earned the rank of Colonel during the early stages of landings. The second stage of the Gallipoli campaign, which was opened on August 6, put Mustafa Kemal only three hundred meters (0.18 miles) away from the firing line. He was the Turkish commander at many major battles throughout the campaign, such as the Battle of Chunuk Bair, Battle of Scimitar Hill and the Battle of Sari Bair.

The Gallipoli campaign ended up to be a disaster for the Allies as they had been pinned down by the Turks during ten months of fighting.[9] The Allies finally decided to call off the offensive and troops were evacuated, with the evacuation being the greatest Allied success. On the Ottoman Empire's side, Otto Liman von Sanders (5th Army) and several other Turkish commanders had significant achievements based on their role in the defense of the Turkish Straits. However, Mustafa Kemal became the outstanding front-line commander and gained much respect from his former enemies for his chivalry in victory. The Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Memorial has an honoured place on ANZAC Day parades in Canberra, Australia. Mustafa Kemal's commemorating speech on the loss of thousands of Turkish and Anzac soldiers in Gallipoli is today inscribed on a monument at Anzac Cove:

"Those heroes who shed their blood and lost their lives… you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours… You, the mothers who sent their sons from far away countries, wipe away your tears. Your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land, they have become our sons as well."

Caucasus Campaign, 1916-1917

Following the Battle of Gallipoli, Mustafa Kemal first served in Edirne until the January 14, 1916. He was assigned to the command of the XVIth Corps of the 2nd Army and sent to the Caucasus Campaign. He was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General on April 1. Most historians believe that Enver Pasha deliberately delayed his promotion.

When Mustafa Kemal was assigned to his new post, the 2nd Army was facing the Russian army under General Tovmas Nazarbekian, the detachment Armenian volunteer units controlled by Andranik Toros Ozanian and the Armenian irregular units which were in constant advance. After the Van Resistance an Armenian provisional government under the leadership of Aram Manougian was formed with a progressive autonomous region.[10][11] The Armenian administration had grown from its initial set-up around Lake Van[12]. The initial stages of the Battle of Bitlis and the Battle of Muş were already developed. On arrival Kemal found chaotic conditions. The region was inhospitable at the best of times.[13]. Communication lines were under insurgency attacks. Hundreds of thousands of refugees, many of them Kurds, which had bitter relations with Armenian units, came flooding in front of the advancing Russian armies.[14] Mustafa Kemal's initial task was to bring order to the scared people so that his corps could function during this human suffering.

The massive Russian offensive reached the Anatolian key cities of Erzurum, Bitlis and Mus. On 7 August, Mustafa Kemal rallied his troops and mounted a counteroffensive [15]. He had so strengthened the morale of his force, following its defeat, that within five days, two of his divisions captured not only Bitlis but the equally important town of Muş, greatly disturbing the calculations of the Russian Command.[16] Emil Lengyel wrote:

- "He demonstrated anew that the Turk was a fine soldier if he was given the right leadership. Again the Turks took note of the uncommon competence of a general whose name was 'Perfection'." [17].

But Izzet Pasha, on the other parts of the front, failed to match these successes. In September, Mustafa Kemal retreated from Muş under the heavy advance of the Russian Army and Armenian volunteer units. However, Mustafa Kemal could claim the only Turkish victory in a round of defeats.[16] He also concentrated on the strategic goal of confining the enemy within the mountainous region.That same year, as a recognition of his military achievements and his success in improving the stability of the region, he was given the medal Golden Sword of the Order of "Imtiyaz".

On March 7, 1917, Mustafa Kemal was appointed from the command of the XVIth Corps to the overall command of the 2nd Army. Meanwhile, Russian Revolution erupted and the Caucasus front of the Czar's armies disintegrated[18]. However, he had assigned to another fighting front and left the region.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign, 1917-1918

His command of the 2nd Army was cut short, as he was transferred to the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. He was assigned the command of the 7th Army. After a short visit to the 7th Army headquarters, he returned back to Istanbul on October 7. He joined the crown prince Mehmed Vahideddin (later Sultan Mehmed VI) on a visit to Germany. During this trip he fell ill and stayed in Vienna for medical treatment.

He returned back to Aleppo on August 28, 1918, and resumed the command of the 7th Army. His headquarters were in Nablus, Palestine. Like in Gallipoli, he was under the command of General Liman von Sanders, whose group headquarters was based in Nazareth. Mustafa Kemal studied Syria thoroughly once again and visited the frontline. His conclusion was that Syria was in a pitiful state (the 1915-1917 period had left 500,000 Syrian casualties to famine.)[19] There was no Ottoman civil governor or commander. There was an abundance of English propaganda and English secret agents were everywhere. The local population hated the Ottoman government and looked forward to the arrival of the British troops as soon as possible. The enemy was stronger than his own forces in terms of men and equipment. To describe the desperate situation, he said "we are like a cotton thread drawn across their path."[20]

Mustafa Kemal also had to deal with the Arab Revolt, organized by Great Britain which encouraged the local Arabs to revolt against the Turkish rule. Liman von Sanders lost the Battle of Megiddo, leaving 75,000 POW behind, on the first day alone. Now, nothing stood between General Allenby's forces and Mustafa Kemal's 7th Army. Concluding that he didn't have enough men to encounter the British forces, Mustafa Kemal retreated towards Jordan for establishing a stronger defensive line. In a couple of days, the total number of the deserters reached 300,000.[21] Mustafa Kemal's war was changed drastically from fighting against the Allies to fighting against the disintegration of his own forces. He sent a furious telegram to Sultan:

"The withdrawal ... could have been carried out in some order, if a fool like Enver Paşa had not been the director-general of the operations, if we did not have an incompetent commander - Cevat Paşa - at the head of a military force of five to ten thousand men, who fled at the first sound of gunfire, abandoned his army, and wandered around like a bewildered chicken; and the commander of the 4th army, Cemal Paşa, ever incapable of analyzing a military situation; and if, above all, we did not have a group headquarters (under Liman von Sanders) which lost all control from the first day of the battle. Now, there is nothing left to do but to make peace."[22]

Mustafa Kemal was appointed to the command of Yıldırım Orduları ( Thunderbolts), replacing Liman von Sanders. In the autumn of 1918 allied forces, having captured Jerusalem, prepared for their final lightening offensive under General Allenby on the Palestine front, in the words of an Arab historian to sweep Turks "like thistledown before the wind".[23] Mustafa Kemal established his headquarters at Katma and succeeded in regaining control of the situation. He allocated his troops along a new defensive line at the south of Aleppo, and managed to resist at the mountains. He stopped the advancing British forces (last engagements of the campaign). Kinross wrote:

" Once again the Turkish hero of the campaign was Mustafa Kemal, who, after a masterly strategic retreat to the heights of Aleppo, found himself in command of the remnants of the Ottoman forces now defending the soil of Turkey itself, of which it was the natural frontier. They were still undefeated when news was received of the signature of an armistice between Britain and Turkey-leaving him, at the end of the struggle, the sole Turkish commander without a defeat to his name. Behind him were those anatolian homelands of the Turkish race, where his future destiny and that of his people lay." [24]

Mustafa Kemal's position became the base line for the peace agreement. His last active service to the Ottoman Army was organizing the return of the troops that were left behind, to the south of his line (Yemen, for instance, was still under Ottoman control when the Armistice of Mudros was signed).

Partitioning of the Empire, 1918

On 30 October, 1918 the Ottomans capitulated to the Allies with the Armistice of Mudros. Beginning with the armistice, the creation of the modern Arab world and Turkey began. As a reaction to the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire, and to the Treaty of Sèvres which further reduced the amount of Turkish-controlled lands in Anatolia, the Turks waged a war of independence, which eventually led to the establishment of the Republic of Turkey. The Arab uprising against the partitioning of the Middle East between the United Kingdom and France (in line with the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1917) developed later, and led to the establishment of independent Arab states such as Syria, Iraq, Kuwait, Jordan, and Lebanon.

At the end of the war, Mustafa Kemal was 37 years old. In the final stages of WWI, he was assigned to command the largest remaining Ottoman Army division, the Yıldırım Orduları. After the armistice, however, the Yıldırım Orduları was dissolved, and Mustafa Kemal returned back to an occupied Istanbul on November 13, 1918. He was given an administrative position at the Ministry of War (Harbiye Nezareti).

The British, Italian, French and Greek forces began to occupy Anatolia with the intention of leaving only a part of Central Anatolia as Turkish territory. The occupation of Istanbul along with the occupation of İzmir mobilized the establishment of the Turkish national movement and the Turkish War of Independence.[25]

War of Independence

Initial organization (May 1919-March 1920)

Mustafa Kemal's active participation in the national resistance movement began with his assignment by the Sultan, Mehmed VI, as a General Inspector to the 9th Army. His task was to oversee the demobilisation of remaining Ottoman military units and nationalist organizations. He departed from Istanbul on board the ferry Bandırma, and landed at Samsun, a port city on the Black Sea coast of Anatolia, on May 19, 1919. The occupations had already generated disorganised local oppositions by numerous militant resistance groups. The establishment of an organised national resistance movement against the occupying forces was the first goal in Mustafa Kemal's mind, and this assignment put him in an ideal position to help organise the resistance.[26] Instead of trying to disarm the nationalist units, he contacted local leaders and started issuing orders to provincial governors and military commanders, calling them to resist the occupations. In June 1919, Mustafa Kemal disclosed his intentions, as he and his close friends issued the Amasya Circular which stated that the independence of the country was in danger and the nation had to save itself by its own will and sources, since the Ottoman government in Istanbul was subject to foreign control.

The British were alarmed when they learned of Mustafa Kemal's activities and immediately contacted the Ottoman government, which issued a warrant for the arrest of Mustafa Kemal, on the charge that he was disobeying the Sultan's order for dissolving the remaining Ottoman forces in Anatolia, later condemning him to death. As a response, Mustafa Kemal resigned from the Ottoman Army on July 8, while he was in Erzurum. Mustafa Kemal called for a national election to establish a new Turkish Parliament that would have its seat in Ankara.[27] The call for an election became successful.

On 12 February, 1920, the last Ottoman Parliament gathered in Istanbul and declared the Misak-ı Milli (National Pact). Parliament then was dissolved by the occupying British forces.

Jurisdictional Conflict (March 1920 - March 1922)

Mustafa Kemal used the dissolution of the Ottoman Parliament in Istanbul as an opportunity to establish a new National Assembly in Ankara. The first session of the "Grand National Assembly of Turkey" gathered on April 23, 1920, with Mustafa Kemal as its president. The declared goal was to "liberate the Sultan".[27]

The Sultan signed the Treaty of Sèvres with the Allies on August 10, 1920, which set up the final plans for the partitioning of Anatolia. The treaty's signing further galvanized the relations between the governments of Istanbul and Ankara, since Mustafa Kemal and his friends deemed unacceptable the terms of the treaty, which would spell the end of Turkish independence. The treaty and the events which followed it weakened the legitimacy of the Sultan's government in Istanbul, and caused a shift of power in favour of the Turkish Grand National Assembly in Ankara. A popular sovereignty law was passed with the new constitution of 1921. This constitution gave Mustafa Kemal the tools to wage a War of Independence, as it refuted the principles of the Treaty of Sèvres by assigning the legality to the "nation" - and not to the monarch or its representative (the Ottoman government in Istanbul). He persuaded the Grand National Assembly to gather a National Army.

Turkish Victory

The National Army, under the command of Mustafa Kemal, faced the Allied occupation forces and fought on three fronts: in the Franco-Turkish, Greco-Turkish and Turkish-Armenian wars.

Insisting on complete independence and the safeguarding of the interests of the Turkish majority on Turkish soil, Mustafa Kemal attacked the acceptance by Damat Ferid Pasha of the principle of Wilsonian Armenia and the proposal for a British protectorate in the rest of Anatolia.[28] Relations were further galvanized after Damat Ferid Pasha signed the Treaty of Sèvres which had proposed to assign the territories gained by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and the surrounding areas to Armenia. The Turkish revolutionaries had never recognized the Sevre treaty. In the early autumn of 1920, the Turkish-Armenian War was waged between the Turkish revolutionaries and the Armenian military. In December 1920, Armenia appealed for peace and signed the Treaty of Alexandropol. After Armenia was incorporated into the Transcaucasian SFSR as a Soviet Socialist Republic, the Treaty of Kars, which replaced the previous agreements, was signed between the Turkish revolutionaries and Bolshevist Russia, Soviet Armenia, Soviet Azerbaijan and Soviet Georgia. This treaty was ratified in Yerevan one more time, after these states officially became a part of the Soviet Union in 1922. The Turks won control over most of the territories in northeastern Anatolia, where they constituted the ethnic majority.

Yet, at the center of the Turkish War of Independence was, above all else, the Greek invasion. It was the Greeks who were trying to conquer Anatolia, and it was they who had to be beaten if other invaders were to be pushed out. After a series of battles, the Greek army advanced as far as to the Sakarya River, just eighty kilometers west of the Grand National Assembly in Ankara. Subsequently, Mustafa Kemal was promoted to be the Commander in chief of the Turkish forces, with full powers. The Turkish Army defeated the Greeks in the twenty-day Battle of Sakarya, which lasted from August 23 to September 13, 1921. Mustafa Kemal returned in triumph to Ankara, where a grateful Grand National Assembly awarded him the rank of Field Marshal of the Army, as well as the title of Gazi, or "Fighter of the Faith against the Infidel".[29]

The final battle for the control of Anatolia was fought during August-September 1922, when Turks launched a counter-attack on August 26th, what has come to be known to the Turks as the Great Offensive (Buyuk Taaruz). Mustafa Kemal chose to adopt the strategy of concentration and surprise, employed by General Allenby against the Turkish forces in Syria, in the closing stages of the first World War. [30] He launched an all-out attack on the Greek lines at Afyon Karahisar, aimed at smashing a hole in the Greek defences, cutting the Greek supply lines and opening the road to Izmir and to the sea.[31] After some hours of resistance, the major Greek defense positions were overrun on August 26. On August 30, the Greek army was defeated decisively at the Battle of Dumlupınar, with half of its soldiers captured or slain and its equipment entirely lost.[32] On September 1, Mustafa Kemal issued his famous order to the Turkish army: "Armies, your first goal is the Mediterrean, Forward!"[33] By 10 September, the remainder of the Greek forces had completely evacuated Anatolia, the Turkish mainland.

Praising Mustafa Kemal's military capabilities, a biographer of him wrote:

- "A man born out of due season, an anachronism, a throwback to the Tartars of the steppes, a fierce elemental force of a man. With his military genius and his ruthless determination,...in a different age he might well have been a Genghis Khan, conquering empires..."[34]

Stage for peace (March 1922- April 1923)

The Treaty of Kars on October 23, 1921, had already settled the conflicts at the eastern border of Turkey and returned the sovereignty of the cities of Kars and Ardahan to the Turks, which were three decades earlier captured by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

The Conference of Lausanne began on November 21, 1922. İsmet İnönü was the leading Turkish negotiator. Ismet maintained the basic position of the Ankara government that it had to be treated as an independent and sovereign state, equal with all other states attending the conference. In accordance with the directives of Mustafa Kemal, while discussing matters regarding the control of Turkish finances and justice, the Capitulations, the Turkish Straits and the like, he refused any proposal that would compromise Turkish sovereignty.[35] Finally, after long debates, on July 24, 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, thus putting an end to long years of warfare which had consumed the country. The territorial integrity of the Turkish nation, as specified by the National Pact which was announced three years earlier, at the beginning of the war of independence, was confirmed (with the exception of regaining full sovereignty over Mosul and Kirkuk, on the oil revenues of which Turkey was given a share; and the cities of Hatay (Antioch) and Iskenderun (Alexandretta), which were later regained by Turkey in 1939.) Through the Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey finally entered into a period of peace.

Turkish Republic and the Kemalist ideology

- For conceptual analysis, see Kemalist ideology

Mustafa Kemal was 42 years old when the Republic of Turkey was declared on October 29, 1923. At the declaration, the public cheered: "We are returning to the days of the first caliphs".[36] Mustafa Kemal placed Fevzi Çakmak, Kazım Özalp and İsmet İnönü in the important positions, where they helped him to establish the reforms which were impossible to foresee back in 1923.

The Treaty of Lausanne ended the Turkish War of Independence and recognized the new nation's independence. However, the war to modernise the country had just started; institutions and constitutions of Western states such as France, Sweden, Italy, or Switzerland were yet to be analyzed and adopted according to the needs and characteristics of the Turkish nation.

In the first years of the republic, it was not just the old regime that wanted to resurface, but new ideologies like communism were struggling for acceptance as well. Mustafa Kemal saw the consequences of fascist and communist doctrines in the 1920s and 1930s and rejected both.[37] Mustafa Kemal prevented the spread of totalitarian party rule which held sway in the Soviet Union, Germany and Italy.[38]The nature of the state built by Kemal, its organization and its functions are summarized in the Kemalist ideology, which was considered to be an ideology of modernisation based on realism and pragmatism.[39] Mustafa Kemal and Turkish revolutionaries were representing the straightforward spirit of Anatolia as opposed to cosmopolitan Istanbul and its Ottoman heritage.[40] However, this was performed by the silencing of other views and putting the state in the center of the society. Some perceived it as the silencing of opposition, some perceived it as preventing the rule of the extremes over the majority.

Popular sovereignty

- For conceptual analysis see Kemalist Populism

We learn from Mustafa Kemal's notes that even before the establishment of the new state (1923), his ideas on democracy differed from the Ottoman experience and were based on the concept of popular sovereignty. Mustafa Kemal visualized a parliamentary sovereignty (a representative democracy) where the Parliament, not the executive, is the ultimate source of sovereignty. However, Kemal approached his goal in small steps. What Mustafa Kemal cultivated between 1919-1920 was much more advanced than the Ottoman Empire's experience with democracy during the (First Constitutional Era and the Second Constitutional Era). Mustafa Kemal promised to have a "direct government by the Assembly" in 1920.[41] He defended the idea that the power of the constitution (sovereignty) originates from the National Assembly (national sovereignty) and not from the absolute monarch, as was the case in the Ottoman Empire. The assembly embodied his position in the constitution of 1921. Mustafa Kemal took the position that the country needed an immense task of reconstruction and this required the ability to make choices among policies. The idea of "direct government by the Assembly" did not survive in this environment. On October 28, 1923, he defended the idea that a government with a Prime Minister alongside the President needed to be established.

Activities towards establishing national sovereignty intensified in 1923, as the initial backbone of legislative, judicial, and executive structures were created. For Mustafa Kemal, total independence was not negotiable.[42] According to him, total independence had three dimensions: economic, civic and religious.

Economic independence

- For conceptual analysis see National economy

Mustafa Kemal held the belief that democracy could not be formed without economic independence. The efforts towards economic independence had begun before the establishment of the Republic. He began working on the abolition of the Capitulations during the Conference of Lausanne, and was adamant that the Capitulations, all unequal concessions to foreigners and minorities, and all outside interference had to go.[42] Mustafa Kemal deadlocked the Conference of Lausanne until the French and Italian economic demands changed.[43]

Civic independence

The second dimensions was the civic law. He said: "We must liberate our concepts of justice, our laws and our legal institutions from the bonds which, even though they are incompatible with the needs of our century, still hold a tight grip on us"[44] The leading legal reforms instituted by Mustafa Kemal included the complete separation of government and religious affairs and the adoption of a strong interpretation of the principle of laïcité in the constitution. This was coupled with the closure of Islamic courts and the replacement of Islamic canon law with a secular civil code modeled after the Swiss Civil Code and a penal code modeled after the Italian Penal Code.

Caliphate

The third dimension was the position of the Caliph. Mustafa Kemal wanted to integrate the powers of the Caliphate into the powers of the Assembly, and his initial activities began on January 1, 1924.[45] Mustafa Kemal acquired the consent of İnönü, Çakmak and Özalp before the abolition of the Caliphate. On March 1, 1924, at the Assembly, Mustafa Kemal said "the religion of Islam will be elevated if it will cease to be a political instrument, as had been the case in the past."[46] In the days that followed, the Assembly transferred the powers of the Ottoman Caliphate into itself (see Abolishment of the Ottoman Caliphate). Mustafa Kemal's only involvement in the rest of this process came in a speech days after, where he said "there is no need to look at this process as something extraordinary."[47] On March 3, 1924, the Caliphate was officially abolished and its powers within Turkey were transferred to the Turkish Grand National Assembly.

Political system

- For the conceptual analysis see Political reforms and Legal reforms

The basic structure of a democracy; elections, assembly, government with a Prime Minister and President was established under Mustafa Kemal's leadership. The political system was based on the single party politics. At first, the only party was the Republican People's Party ("Cumhuriyet Halk Fırkası" in Turkish) which was founded by Mustafa Kemal on September 9, 1923. The extent of his leadership is sometimes questioned. There are historians who claim that Mustafa Kemal did not promote democracy, yet as his biographer notes "between the two wars, democracy could not be sustained in many relatively richer and better-educated societies. Atatürk's enlightened authoritarianism left a reasonable space for free private lives. More could not have been expected in his lifetime."[48] During a speech about the political system in 1933, Mustafa Kemal claimed that "Republic means democratic administration of the state. We founded the Republic, reaching its tenth year it should enforce all the requirements of democracy as the time comes."[49]. As in other reform areas, which were imposed through non-democratic methods to develop a democratic Republic, Mustafa Kemal was a realist regarding the limits of sustainable development.

Multiparty periods

Mustafa Kemal's cultural revolution faced opposition. In 1925, the establishment of another political party was seen as a way to ease the tensions. Mustafa Kemal asked Kazım Karabekir to establish the Progressive Republican Party as an opposition party in the Assembly, and the first two-party era began. The party's economic program suggested liberalism, in contrast to state socialism, and its social program was based on conservatism in contrast to modernism. Leaders of the party strongly supported the Kemalist revolution in principle, but had different opinions on the cultural revolution and the principle of secularism.[50]

After some time, the new party was taken over by people Atatürk considered as Islamic fundamentalists. In 1925, partly in response to the Sheikh Said Rebellion of Sheikh Said Piran, the "Maintenance of Order Law" was passed, giving Atatürk the authority to shut down subversive groups. Soon after the Sheikh Said Rebellion, the Progressive Republican Party was disestablished under a new law, an act Mustafa Kemal claimed was necessary for preserving the Turkish state. The closure of the party was seen by some later biographers, such as Harold C. Armstrong, as an act of dictatorship.[51]

On August 11, 1930, Mustafa Kemal decided to try a democratic movement once again. He assigned Ali Fethi Okyar to establish a new party. In Mustafa Kemal's letter to Ali Fethi Okyar, laicism was insisted on. At first, the brand-new Liberal Republican Party succeeded all around the country. But once again the opposition party became too strong in its opposition to Atatürk's reforms, particularly in regard to the role of religion in public life. Finally, seeing the rising fundamentalist threat and being a staunch supporter of Atatürk's reforms himself, Ali Fethi Okyar abolished his own party and Mustafa Kemal never succeeded in establishing a long lasting multi-party parliamentary system. He sometimes dealt sternly with the opposition in pursuing his main goal of democratizing and modernizing the country.

Economic policies

- For the conceptual analysis see Economic reforms

Mustafa Kemal instigated economic policies not just to develop small and large scale businesses, but also to create social strata that were virtually non-existent during the Ottoman Empire, such as an industrial bourgeoise. However, the primary problem faced by the Kemalist state politics was the lag in the development of political institutions and social classes which would steer such social and economic changes.[52]

Due to the lack of any real potential investors to open private sector factories and develop industrial production, Atatürk's activities regarding the economy included the establishment of many state-owned factories throughout the country for agriculture, machinery, and textile industries, many of which grew into successful enterprises and became privatized during the latter half of 20th century. Atatürk considered the development of a national rail network as another important step for industrialization, and this was addressed by the foundation of the Turkish State Railways in 1927, setting up an extensive railway network in a very short time.

State intervention, 1923-1929

Mustafa Kemal and İsmet İnönü promoted state projects. Their goal was to knit the country together, eliminate the foreign control of the economy, and improve communications. Istanbul, a trading port with international foreign enterprises, was deliberately abandoned and resources were channeled to other, relatively less developed cities, in order to establish a more balanced development throughout the country.[53] The choices that Mustafa Kemal made on economic policies were a reflection of the realities of his time. The Anatolian economy was based on agriculture, with primitive tools and methods; roads and transportation facilities were far from sufficient; and the management of the economy was inefficient. Turkish State Railways, and banks like Sümerbank and Etibank were founded.

The Great Depression, 1929

The Great Depression hit very hard on Turkey. The young republic, like the rest of the world, found itself in a deep economic crisis: the country could not finance essential imports; its currency was shunned; and zealous revenue officials seized the meager possessions of peasants who could not pay their taxes.[53] Mustafa Kemal had to face the same problems which all the countries faced: political upheaval. The Liberal Republican Party came out with a liberal program and proposed that state monopolies should be ended, foreign capital should be attracted, and that state investment should be curtailed. Mustafa Kemal supported İnönü's point of view that "it is impossible to attract foreign capital for essential development". However, the effect of free republicans was felt strongly and state intervention was replaced with moderate state intervention, which was not close to capitalism; but a form of state capitalism. One of Mustafa Kemal's radical left-wing supporters, Yakup Kadri Karaosmanoğlu (from the Kadro (The Cadre) movement), claimed that Mustafa Kemal found a third way between capitalism and socialism in his Marxist journal.[54]

Cultural revolution

The first public mention of Mustafa Kemal's program to implement cultural revolution came at speech in Bursa:

"A nation which does not practice science has no place in the high road of civilization. But our nation, with its true qualities, deserves to become - and will become - civilized and progressive."

Mustafa Kemal capitalized on his reputation as an efficient military leader and spent his following years, up until his death in 1938, instituting wide-ranging and progressive political, economic, and social reforms, transforming Turkish society from perceiving itself as Muslim subjects of a vast Empire into citizens of a modern, democratic, and secular nation-state.

Educational reforms

- For the conceptual analysis see Educational reforms

Mustafa Kemal's idea of national development was all-encompassing, see Atatürk's educational reforms. Besides general education, he was interested in forming a background (skill base) in the country through adult education. His adult education ideas found its way in People's Houses. Turkish women were taught not only child care, dress-making and household management, but also the tools which they could use to become part of general economy. He summarized the adult education as "to equip the new generations at all education levels with knowledge that shall make them efficient and successful in practical and especially economic life." Kemal also linked the educational reform to the liberation of the nation from the dogma, which he believed was even more important than the Turkish war of independence. "Today, our most important and most productive task is the national education [unification and modernization] affairs. We have to be successful in national education affairs and we shall be. The liberation of a nation is only achieved through this way."

Modernization of education

Mustafa Kemal invited John Dewey in the summer of 1924 in order to receive advice that would provide ideas for reforms and recommendations benefiting the Turkish educational system, and to propel it towards a modern educational establishment [55]. Literate citizens used the Ottoman Language written in Arabic script with the Arabic and Persian loan vocabulary, although this group comprised as few as 10% of the population[55]. In order for citizens to assume roles in public life, it was recognized that they would need at least a basic level of literacy. Mustafa Kemal initiated his reforms on public education to enhance public literacy. Kemal wanted to have compulsory primary education for both girls and boys; since then this effort has been an ongoing task for the Republic. In order to promote social change from traditional to modern ways, Kemal assigned high importance to literacy[55]. Dewey notes that roughly three years were necessary to learn to read and write in Arabic script on an elementary level with rather strenuous methods[55]. At the initiative of Atatürk, the creation of the new Turkish alphabet as a variant of the Latin alphabet was undertaken by the Language Commission (Dil Encümeni)[55]. The Turkish alphabet was decreed on 24 May 1928, and by 15 December of that year the first of many Turkish newspapers was published with the use of the new alphabet. Kemal also promoted the modern teaching and learning methods in elementary education in which Dewey took a place of honor; as Dewey's "Report and Recommendation" for the Turkish educational system at the time was a paradigmatic recommendation for an educational policy of developing societies moving towards modernity.[55].

Another important part of Atatürk's reforms encompassed his emphasis on the Turkish language and history, leading to the establishment of the Turkish Language Association (Türk Dil Kurumu) and the Turkish Historical Society (Türk Tarih Kurumu) between 1931 and 1932, for conducting research works on Turkish language and history. The fast adoption of the new alphabet was the result of the combined effect of opening the People's Houses (tr: Halk Evleri) throughout the country and the active encouragement of people by Atatürk himself, who made many trips to the countryside in order to teach the new alphabet. The literacy reform was also supported by strengthening the private publishing sector with a new Law on Copyrights and congresses for discussing the issues of copyright, public education and scientific publishing.

Unification of education

Kemal modernized the old medrese education[55]. Mustafa Kemal changed the classical Islamic education with a vigorously promoted reconstruction of educational institutions along the line of an enlightened pragmatism[55]. Kemal's new "unified" educational system designated a responsible citizen as well as a useful and appreciated member of the society[55].

Social reforms

It is evident from his personal journal that Mustafa Kemal began to develop the concepts of his social revolution very early. Mustafa Kemal constantly discussed with his staff on issues like abolishing the veiling of women and integration of females to social life, and developed conclusions. In November 1915, Mustafa Kemal wrote in his journal that "the social change can come by (1) educating capable mothers who are knowledgeable about life; (2) giving freedom to women; (3) a man can change his morals, thoughts, and feelings by leading a common life with a woman; as there is an inborn tendency towards the attraction of mutual affection."[56]

In Mustafa Kemal's world there was no dualism. He enforced his ideas to full extent. According to Mustafa Kemal, a progressive nation also was progressive in understanding its belief system. Mustafa Kemal commissioned the translation of Quran into Turkish and he himself read it in front of the public in 1932.[57]

Notwithstanding the Islamic prohibition against the consumption of alcoholic beverages, he encouraged domestic production of alcohol and established a state-owned spirits industry. He was known to have an appreciation for the national beverage, rakı, and enjoyed it in vast quantities.[58]

Decree on dress

- For the conceptual analysis see Dress code

The Decree on dress targeted the religious insignia used outside times of worship. Kemal passed a series of laws beginning from 1923, especially the Hat Law of 1925 which introduced the use of Western style hats instead of the fez, and the Law Relating to Prohibited Garments of 1934, which emphasized the need to wear modern suits instead of antiquated religion-based clothing such as the veil and turban. The guidelines for the proper dressing of students and state employees (public space controlled by state) was passed during his lifetime. Mustafa Kemal regarded the fez (in Turkish "fes", which Sultan Mahmud II had originally introduced to the Ottoman Empire's dress code in 1826) as a symbol of oriental backwardness and banned it. He encouraged the Turks to wear modern European attire.[59]. He was determined to force the abandonment of the sartorial traditions of the Middle East and finalize a series of dress reforms, which were originally started by Mahmud II[59]. Mustafa Kemal first made the hat compulsory to the civil servants[59]. After most of the relatively better educated civil servants adopted the hat with their own free will, in 1925 Mustafa Kemal wore his "Panama hat" during a public appearance in Kastamonu, one of the most conservative towns in Anatolia, to explain that the hat was the headgear of civilized nations.

One of Atatürk’s goals was to improve the status of Turkish women and integrate them more thoroughly into the society.

Women’s rights

- For the conceptual analysis see Women’s rights

Mustafa Kemal did not consider the gender as a factor in social organization. According to his view, society marched towards its goal with all its women and men together. It was scientifically impossible for him to achieve progress and to become civilized if the gender separation continued as in the Ottoman times[60]. He said "everything we see on Earth is the product of women" and the Turkish woman should be brought to the status which she deserved. The place of women in Kemal's cultural reforms was best expressed in the civic book that was prepared under his supervision.[61] Kemal said that "there was no logical explanation for the political disenfranchisement of women. Any hesitation and negative mentality on this subject is nothing more than a fading social phenomenon of the past. ……Women must have the right to vote and to be elected; because democracy dictates that, because there are interests that women must defend, and because there are social duties that women must perform."[62]

The reforms instituted legal equality between the sexes and the granting of full political rights to women on December 5, 1934, well before several other European nations. However, the change was not easy. In the last election which Atatürk had the chance to observe (the 1935 elections), there were only 18 female MPs out of a total of 395 representatives. When it came to women's rights, Atatürk was a firm believer that these specific reforms should not be forced into society, but adapted by women themselves. During his policy making, he did not pass a law on the minimum quota of female representatives. He believed that the cultural practices occupied a wider effect on the participation of women in the social life than the laws.

He saw secularism as an instrument to achieve this goal. Even though he personally promoted modern dress on women, he never made specific reference to women’s clothing in the law. In the social conditions of the 1920s and 1930s, he believed that women would adapt to the new way with their own will. He was frequently photographed on public business with his wife Lâtife Uşaklıgil, who covered her head. He was also frequently photographed on public business with women wearing modern clothing.

He wrote: "The religious covering of women will not cause difficulty.... This simple style [of headcovering] is not in conflict with the morals and manners of our society."[63] He married Lâtife Uşaklıgil with a civil ceremony in contrast to a religious one. It was a major step in the 1920s society. Simultaneously, legislators had accepted the Swiss civil code which defined the rights of women in a marriage as equal to men.[64]

Arts

Mustafa Kemal believed in the supreme importance of culture; which he expressed with the phrase "culture is the foundation of the Turkish Republic."[65] His view of culture included both his own nation's creative legacy and what he saw as the admirable values of global civilization, putting an emphasis on humanism above all. He once described modern Turkey's ideological thrust as "a creation of patriotism blended with a lofty humanist ideal."

In 1934, upon Mustafa Kemal's order, Semiha Berksoy played the leading role in "Özsoy" (composed by Adnan Saygun), the first ever Turkish opera work, staged at the People's House in Ankara.[66]

To assist in the creation of such a synthesis, Atatürk stressed the need to utilize the elements of the national heritage of the Turks and of Anatolia, including its ancient indigenous cultures as well as the arts and techniques of other world civilizations, both past and present. He emphasized the study of earlier civilizations, foremost of which being the Sumerians, after whom he established "Sümerbank", and the Hittites, after whom he established "Etibank", as well as other Anatolian civilizations such as the Phrygians and Lydians. The pre-Islamic culture of the Turks became the subject of extensive research, and particular emphasis was laid upon the fact that, long before the Seljuk and Ottoman civilizations, the Turks have had a rich culture. Atatürk also stressed the folk arts of the countryside as a wellspring of Turkish creativity.

The visual and the plastic arts, whose development had on occasion been arrested by some Ottoman officials claiming that the depiction of the human form was idolatry, were highly encouraged and supported by Atatürk, and these flourished in the new Turkish Republic. Many museums were opened, architecture began to follow modern trends, and classical Western music, opera, and ballet, as well as the theatre, also took greater hold. Several hundred "People's Houses" (Halk Evi) and "People's Rooms" (Halk Odası) across the country allowed greater access to a wide variety of artistic activities, sports, and other cultural events. Book and magazine publications increased as well, and the film industry began to grow.

Criticism

Atatürk's reforms were regarded as being too rapid by some. In his quest to modernize Turkey, he effectively abolished centuries-old traditions by means of reforms to which much of the population was unaccustomed but nevertheless willing to adopt. In some cases, these reforms were seen as benefiting the urban elites rather than the generally illiterate inhabitants of the rural countryside,[67] where religious sentiments and customary norms tended to be stronger. In particular, Atatürk's strict religious reforms met with some opposition, and they continue to generate a considerable degree of social and political tension to this day. In the future, political leaders would draw upon dormant forces of religion in order to secure positions of power, only to be blocked by the interventions of the powerful military (as in 1960 when Prime Minister Adnan Menderes was overthrown by the military),[68] which has always regarded itself as the principal and most faithful guardian of secularism.[citation needed]

Atatürk and the Kurds

During the years of the War of Independence, Atatürk recognized the multiethnic character of the Muslim population in Turkey. On December 8, 1925, the Turkish Ministry of Education issued an order[citation needed] banning the use of ethnic terms such as Kurd, Circassian, Laz, Kurdistan and Lazistan.[69]

On February 13, 1925, an externally guided uprising for an independent Kurdistan broke out in the Dersim region of the upper Euphrates, led by Sheikh Said Piran, the rich hereditary chieftain of the local Nakshibendi dervishes. Sheikh Said chose to emphasize the issue of religion above that of Kurdish nationalism. The Sheikh stirred up his tribesmen against the abolition of the Caliphate and the policies of the Kemalist government which he considered as against religion. Some members of the government saw the revolt as an attempt at a counter-revolution, which could have spread to other parts of the country, and urged for an immediate military action. Beneath the Islamic green banner, in the name of the restoration of the Holy Law, his forces roamed through the country, seized government offices and marched on the important cities of Elazığ and Diyarbakır.[70] By the end of March 1925, the necessary troop movements were completed, and the whole area of the rebellion was encircled, with Sheikh Said blockaded within his own territory of revolt.[71] Then the revolt was put down quickly. Said and 36 of his followers were condemned to death for treason and hanged. Several other large-scale Kurdish revolts occurred in Ağrı and Dersim in 1930 and 1937.[72][73] Turkish Air Force used aerial bombardments effectively against Kurdish uprisings. Sabiha Gökçen, the first female combat pilot of the world and the adopted daughter of Atatürk, took part in the bombing raids against the Dersim Kurds.[72]

Atatürk explained his new policy in the manual of civics which he dedicated to his adopted daughter Afet İnan in 1930:

"Within the political and social unity of today's Turkish nation, there are citizens and co-nationals who have been incited to think of themselves as Kurds, Circassians, Laz or Bosnians. But these erroneous terms have brought nothing but sorrow to individual members of the nation, with the exception of a few brainless reactionaries, who became the enemy's instruments."[69]

On 12 November 1937, Atatürk left Ankara to pay a last visit to southeast Anatolia. During his visit, he issued an order that the cities Diyarbekir and Elaziz should be renamed as Diyarbakır and Elazığ. This was in accordance[citation needed] with the Sun Theory of Languages which maintained that all words of foreign origin had Turkish roots.[74]

Last days, 1937-1938

During 1937, indications of Atatürk's worsening health started to appear, and while he was on a trip to Yalova during the beginning of 1938, he suffered serious illness. After a short period of treatment in Yalova, an apparent improvement in his health was observed, but his condition again worsened following his journeys first to Ankara, and then to Mersin and Adana, in relation to the political developments regarding the status of the Republic of Hatay. Upon his return to Ankara in May, he was recommended to go to İstanbul for recovery and treatment, where he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver.

During his time in İstanbul, he made an effort to keep up with his regular lifestyle for a while, heading the Council of Ministers meeting, working on the Hatay issue, and hosting the King Carol II of Romania during his visit in June. He stayed onboard his newly arrived yacht, Savarona, until the end of July, after which the status of his health again worsened and he moved to a room arranged for him at the Dolmabahçe Palace. On his will written on September 5, 1938, he donated all of his possessions to the Republican People's Party, bound to the condition that, through the yearly interest of his funds, his sister Makbule and his adopted children will be looked after, the higher education of the children of İsmet İnönü will be funded, and the Turkish Language Association and Turkish Historical Society will be given the rest.

Funeral

Atatürk died at the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul, on November 10, 1938, at the age of 57. It is thought that he died of cirrhosis of the liver.[75] Atatürk's funeral called forth both sorrow and pride in Turkey, and seventeen countries sent special representatives, while nine contributed with armed detachments to the cortège.[76]

On November 1953, Mustafa Kemal's remains were taken from the Ethnography Museum of Ankara by 138 young reserve officers in a procession that stretched for two miles including the President, the Premier, every Cabinet minister, every parliamentary deputy, every provincial governor and every foreign diplomat, while at the same time 21 million Turks stood motionless all over the country.[77] One admiral guarded a velvet cushion which bore the Medal of Independence; the only decoration, among many others, that Atatürk preferred to wear. The Father of the Turks finally came to rest at his mausoleum, the Anıtkabir. An official noted: "I was on active duty during his funeral, when I shed bitter tears at the finality of death. Today I am not sad, for 15 years have taught me that Atatürk will never die."[77]

His lifestyle had always been strenuous. Alcohol consumption during dinner discussions, smoking, long hours of hard work, very little sleep, and working on his projects and dreams had been his way of life. As the historian Will Durant had said, "men devoted to war, politics, and public life wear out fast, and all three had been the passion of Atatürk."

Family and personal life

Mustafa Kemal married only once. He married Latife Uşaklıgil on January 29, 1923. The marriage lasted until August 5, 1925. The circumstances of their divorce remain publicly unknown. A 25-year old court order banned the publishing of his former wife's diaries and letters, which may have contained information on the issue. Upon expiration of the court order, the head of the Turkish History Foundation, where the letters are kept since 1975, said Latife Uşaklıgil's family had demanded that the letters remain secret.[78]

Atatürk adopted his daughters Afet (İnan), Sabiha (Gökçen), who later became the first female combat pilot in the world, Fikriye, Ülkü, Nebile, Rukiye, Zehra and his son Mustafa.[79] Additionally, he had two children under his protection, Abdurrahim and İhsan. Out of the 5 siblings of Atatürk, four died at early ages and only his sister Makbule (Atadan) survived, living until 1956.

In times of leisure, he mainly enjoyed reading, horse riding, chess, and swimming. He was very interested in dancing, taking pleasure in waltz on almost every opportunity, as well as the traditional Zeybek folk dances. He also had an appreciation of Rumelian folk songs. He attached importance to his horse Sakarya and his dog Fox. Atatürk was fluent in French and German, and maintained a rich personal library of books on politics, history, chemistry, and linguistics.

Selected publications

- "Tâbiye Meselesinin Halli ve Emirlerin Sureti Tahririne Dair Nesayih"

- "Takımın Muharebe Talimi", published in 1908 (Translation from German)

- "Cumalı Ordugâhı - Süvari: Bölük, Alay, Liva Talim ve Manevraları", published in 1909

- "Tâbiye ve Tatbikat Seyahati", published in 1911

- "Bölüğün Muharebe Talimi", published in 1912 (Translation from German)

- "Zabit ve Kumandan ile Hasbihal", published in 1918

- "Nutuk", published in 1927

- "Vatandaş İçin Medeni Bilgiler", published in 1930 (For high school civic classes)

- "Geometry", published in 1937 (For high school math classes)

His daily journals and military notes during the Ottoman period were published as a collection. There is another collection which covers the period between 1923-1937 and indexes all the documents, notes, memorandums, communications (as a President) under multiple volumes, titled Atatürk'ün Bütün Eserleri (All Works of Atatürk).

Legacy

Peace at home, peace in the world

Mustafa Kemal said; "what particularly interests foreign policy is the internal organization of the state. It is necessary that foreign policy should agree with the internal organization." He eternalized this view with his famous motto "peace at home, peace in the world." He worked to establish his vision, which was evident in his funeral.[76] This was not a random choice as Mustafa Kemal's foreign policy, but was an extension of the domestic needs of the newly established state; as the internal organization and stability of the young Turkish Republic depended on the application of this foreign policy. In achieving this goal, Mustafa Kemal hosted visits by many foreign monarchs and heads of state to Ankara and Istanbul including, in chronological order, King Amanullah Khan of Afghanistan (May 1928), Prime Minister of Hungary Count István Bethlen (October 1930), King Faisal I of Iraq (June 1932), Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos of Greece (October 1932), King Alexander I of Yugoslavia (October 1933), Shah Reza Pahlavi of Persia (June 1934), King Gustav V Adolf of Sweden (October 1934), King Edward VIII of the United Kingdom (September 1936), King Abdullah I of Jordan (June 1937), and King Carol II of Romania (June 1938). Many of the visits meaningfully coincided with the Republic Day, October 29, the anniversary of the declaration of the new Turkish Republic by the Turkish Grand National Assembly, in 1923.

Mustafa Kemal participated in forging close ties with the former enemy, Greece, culminating in a visit to Ankara by the Greek premier Eleftherios Venizelos, in 1932. Venizelos even forwarded Atatürk's name for the 1934 Nobel Peace Prize,[80] highlighting the mutual respect between the two leaders. Atatürk was visited in 1931 by General Douglas MacArthur of the United States, during which the two exchanged their views on the state of affairs in Europe which would eventually lead to the outbreak of World War II. MacArthur expressed his admiration of Atatürk on many occasions and stated that he "takes great pride in being one of Atatürk's loyal friends."[81]

Turkey

His successor, İsmet İnönü, fostered a posthumous Atatürk personality cult which has survived to this day, even after Atatürk's own Republican People's Party lost power following democratic elections in 1950. Atatürk's face and name are seen and heard everywhere in Turkey: his portrait can be seen in all public buildings, in schools, in all kinds of school books, on all Turkish banknotes, and in the homes of many Turkish families. Even after so many years, on November 10, at 09:05 a.m. (the exact time of his death), almost all vehicles and people in the country's streets will pause for one minute in remembrance of Atatürk's memory.

He is commemorated by many memorials throughout Turkey, like the Atatürk International Airport in Istanbul, Atatürk Bridge over the Golden Horn (Haliç), Atatürk Dam, Atatürk Stadium, and Anıtkabir, the mausoleum where he is now buried. Giant Atatürk statues loom over Istanbul and other Turkish cities, and practically any larger settlement has its own memorial to him. In 1981, the Turkish Parliament issued a law (5816) outlawing insults to his legacy or attacks to objects representing him.

Atatürk sought to modernize and democratize the new Turkish Republic, which rose from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire. In his quest to do so, he had implemented far-reaching reforms, the consequence of which has led Turkey towards the European Union today.

Worldwide

In 1981, the centennial of Atatürk's birth, the memory of Atatürk was honored by the United Nations and UNESCO, which declared it The Atatürk Year in the World and adopted the Resolution on the Atatürk Centennial.

There are several memorials to Atatürk internationally. The Atatürk Memorial in Wellington, New Zealand (which also serves as a memorial to the ANZAC troops who died at Gallipoli); the Atatürk Memorial in the place of honour on ANZAC drive in Canberra, Australia; the Atatürk Forest in Israel; and the Atatürk Square in Rome, Italy, are only a few examples. He also has a road named after him in the heart of Islamabad in Pakistan, the Atatürk Avenue, which is one of the busiest and best-known streets of the city. His statues have been erected in numerous parks, streets and squares of many different countries in the world. The famous Madame Tussauds Museum in London has a wax statue of Atatürk.

Media

- Media:Atatürk's 10th anniversary speech.ogg (The sound file of the speech by Atatürk, 1933)

- (The sound file of the message by U.S. President John F. Kennedy on Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1963)

- File:JFKennedy1963 text.pdf (The Text of the message by President John F. Kennedy on Atatürk)

- File:IsmetInonu1963.ogg (The sound file of the message by President İsmet İnönü on Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, November 10, 1963)

(The Text of the message by President İsmet İnönü on Atatürk)

(The Text of the message by President İsmet İnönü on Atatürk)- (The sound file of the message by President Cemal Gürsel on Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, November 10, 1963)

- File:CemalGursel1963 text.pdf (The Text of the message by President Cemal Gürsel on Atatürk)

See also

- Kemalist ideology (Kemalism)

- Atatürk's Reforms

- Atatürk and Kurds

- İsmet İnönü

- Politics of Turkey

- Republican People's Party (Turkey)

- History of the Republic of Turkey

- Timeline of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

- Atatürk Centennial

Notes

- ^ Erik J. Zurcher, p. 142

- ^ http://www.mevzuat.adalet.gov.tr/html/1117.html In Turkish

- ^ http://www.turkishembassy.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=300&Itemid=317

- ^ Turkey : a modern history / Erik J. Zürcher, London ; New York : I.B. Tauris, 2004, p. 142 ISBN 1850433992

- ^ Kinross, p. 60

- ^ a b Australian Government (2007). "The dawn of the legend: Mustafa Kemal". Avustralian Government. Retrieved 2007-03-23.

- ^ BBC News. "Gallipoli: Heat and thirst". Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ BBC News. "Gallipoli: Heat and thirst". Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ BBC News. "Gallipoli: Heat and thirst". Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ^ See: Western

- ^ The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: edited by Richard G Hovannisian

- ^ See: Transcaucasia

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 160

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 161

- ^ They called him Atatürk, the life story of the hero of the Middle East/ Emil Lengyel, New York : John Day Company, 1962, p.68

- ^ a b Patrick Kinross Atatürk, Rebirth of a Nation p.100

- ^ Emil Lengyel, p. 68

- ^ Emil Lengyel, p. 68

- ^ The famine of 1915-1918 in greater Syria,” in John Spangnolo, ed., Problems of the Modern Middle East in Historical Perspectives (Reading, 1992), p.234-254.

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 179

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 180

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 181

- ^ The Ottoman centuries : the rise and fall of the Turkish empire, Lord Kinross, p. 608 ISBN 0688080936

- ^ Kinross, the Ottoman centuries, p. 608

- ^ Mustafa Kemal Pasha's speech on his arrival in Ankara in November 1919

- ^ Feroz Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, p 49

- ^ a b Feroz Ahmad, The Making of Modern Turkey, p 50

- ^ Kinross. Ataturk, p. 169

- ^ History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey, Stanford j. Shaw, Cambridge University Press, p. 357

- ^ Macfie, p. 123

- ^ Macfie, p. 123

- ^ Shaw, p. 362

- ^ Shaw, p. 362

- ^ Barber, Noel, 1988, Lords of the Golden Horn : from Suleiman the Magnificent to Kamal Ataturk, p. 265

- ^ Stanford J. Shaw, p. 365

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 394

- ^ J. M. Landau "Atatürk and the Modernization of Turkey" page 252

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mango501was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Donald Everett Webster "The Turkey of Atatürk: social process in the Turkish reformation" page 245.

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 391-392

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 362

- ^ a b Mango, Ataturk, p. 367

- ^ Treaty of Lausanne (1923), mainly by Article 28

- ^ Yüksel Atillasoy "Mustafa Kemal Ataturk: First President and Founder of the Turkish Republic" page 13.

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 401

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 404

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 405

- ^ Mango, Ataturk. p.536

- ^ (Afet İnan, 1968, Atatürk Hakkında Hatıralar ve Belgeler, Ankara, Türkiye İş Bankası Yayınları. page 260)

- ^ Political Opposition in the Early Turkish Republic: The Progressive Republican Party, 1924-1925 by Erik Jan Zürcher Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 113, 1993

- ^ Armstrong, Harold Courtenay (1972), Grey Wolf, Mustafa Kemal: An Intimate Study of a Dictator. Beaufort Books; Reprint edition. ISBN 0836969626.

- ^ Samuel P. Huntington, "Political Order in Changing Societies" chapter 6 comparative analysis of the Reform strategies of the Atatürk

- ^ a b Mango, Ataturk, p. 470

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 478

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ernest Wolf-Gazo "John Dewey in Turkey: An Educational Mission" Journal of American Studies of Turkey 3 (1996): 15-42.

- ^ Mango, Ataturk, p. 164

- ^ William L. Cleveland "A History of the Modern Middle East" page 178

- ^ The Psychoanalytic Study of Society, IX. 1981: "Immortal" Atatürk — Narcissism and Creativity in a Revolutionary Leader. Vamik D. Volkan, pp. 221–255. [1]

- ^ a b c Turkish National Commission for UNESCO (1963), "Atatürk" pages 165-170

- ^ Gurbuz Tufekci,1981, "Universality of Atatürk’s Philosophy", Turkish Min. of Foreign Affairs

- ^ "Vatandaş İçin Medeni Bilgiler", published in 1930 (For high school civic classes)

- ^ Afet Inan, 1998, "Medeni Bilgiler", Turk Tarih Kurumu

- ^ Quoted in Atatürkism, Volume 1 (Istanbul: Office of the Chief of General Staff, 1982), p. 126.

- ^ rights of women in a marriage

- ^ Yuksel Atillasoy "Mustafa Kemal Ataturk: First President and Founder of the Turkish Republic" page 15.

- ^ Paydak, Selda (2000-01-01). "Interview with Semiha Berksoy". Representation of the European Commission to Turkey. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kinross p.503

- ^ Kinross p.504

- ^ a b Andrew Mango, Atatürk and the Kurds, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol.35, No.4, 1999, p.20

- ^ Patrick Kinross,Atatürk, The Rebirth of a Nation, p.397

- ^ Kinross, p. 401

- ^ a b Olson, R., The Kurdish Rebellions of Sheikh Said (1925), Mt. Ararat (1930), and Dersim (1937-8): Their Impact on the Development of the Turkish Air Force and on Kurdish and Turkish Nationalism, Die Welt des Islam, New Ser., Vol.40, Issue 1, March 2000

- ^ Olson, Robert W., The Emergence of Kurdish Nationalism and the Sheikh Said Rebellion, 1880-1925, 1989

- ^ Andrew Mango, Atatürk and the Kurds, Middle Eastern Studies, Vol.35, No.4, 1999, p.21

- ^ http://www.nndb.com/people/449/000092173/

- ^ a b Mango, Ataturk p. 526

- ^ a b ""The Burial of Atatürk"". Time Magazine. Time co. Monday, Nov. 23, 1953. pp. 37–39. Retrieved 2007-1-1.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ [ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4235691.stm BBC News Ataturk diaries to remain secret (Friday, 4 February, 2005)]

- ^ Terra Anatolia — Mustafa Kemal Ataturk (1881–1938)

- ^ Nobel Foundation. The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1955.[2]

- ^ Handnote by General Douglas MacArthur on display at Anıtkabir

References

- Kinross, Patrick (2003). Atatürk: The Rebirth of a Nation. Phoenix Press. ISBN 1-84212-599-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Mango, Andrew (2004). Atatürk: The Biography of the founder of Modern Turkey. John Murray. ISBN 0719565928.

- Emil Lengyel (1962). They called him Ataturk, The life story of the hero of the middle east. The John Day Company, New York. ISBN 0120-0150.

External links

- Ataturk.org, Site with general information on the founder and first president of the Turkish Republic.

- Ataturk.net, a website dedicated to Atatürk Template:Tr icon

- Onderataturk.com, Ulu Önder Mustafa Kemal Atatürk Template:Tr icon

- Longest Atatürk Biography Template:Tr icon

- His biography and reforms

- Atatürk Gallery by the Ministry of Culture, Republic of Turkey

- Biography, the Revolutions and a speech excerpt from the Ministry of Culture, Republic of Turkey

- Atatürk Biography

- Memorial to Ataturk in Istanbul at the Sites of Memory webpage

- www.turkishnews.com/Ataturk/life.htm Turkishnews.com — Atatürk's life

- Ataturk Center of Azerbaijan Template:Az icon

- Ataturks Life

- Atatürk Resimleri ve Anıları - Eserleri - Hayatı Üzerine Yazılar

- Fotoğraflarla Atatürk

- Milli Mutabakat Atatürk Fotoğrafları

- Atatürk Hollanda Başlangıç Sayfası

- Geniş Arşivi ile Atatürk Sitesi

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 1)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 2)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 3)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 4)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 5)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 6)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 7)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 8)

- Video: Atatürk documentary (Part 9)

- Video: Atatürk, accompanied by Charles H. Sherrill, U.S. Ambassador to Turkey (1932-1933) in Ankara, extends a message of friendship to the American nation

- Video with Turkish sound of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, accompanied by Charles H. Sherrill, U.S. Ambassador to Turkey, expressing vision for a Turkish-American partnership for democracy, peace and prosperity to all mankind

Template:Turkey-related topics

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA ru-sib:Ататюрк, Мустафа Кемаль

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

- Field Marshals of Turkey

- Ottoman Empire and World War I

- Leaders of political parties in Turkey

- Pashas

- People from Thessaloniki

- Presidents of Turkey

- Prime Ministers of Turkey

- Revolutionaries

- Speakers of the Parliament of Turkey

- Turkish War of Independence

- Turkish people of World War I

- 1881 births

- 1938 deaths

- Deaths from cirrhosis