Dextropropoxyphene

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 3.6–6.5 hours[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.747 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H29NO2 |

| Molar mass | 339.471 g·mol−1 |

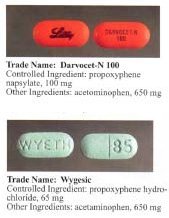

Dextropropoxyphene is an analgesic in the opioid category. It is used to treat mild to moderate pain and as an antitussive. It can be used to ease pain before, during and after an operation. It is often combined with paracetamol (Acetaminophen) in the preparation co-proxamol, however, there is no evidence that this combination is any more effective than paracetamol alone (This combination is known as Darvocet or Balacet in the US and Capadex or Di-Gesic in Australia). Conversely there is no evidence that paracetamol (Acetaminophen) is any more, or even as effective as co-proxamol. There is significant anecdotal evidence that co-proxamol is more effective from the actual patients in pain than paracetamol (Acetaminophen). So much so, that in the United Kingdom, the issue of co-proxamol removal by the MHRA has reached the rarefied level of not one, but two House of Commons Parliamentary debates.

It is manufactured and marketed by Eli Lilly and Company.

It is an optical isomer of Levopropoxyphene. The racemic mixture is called Propoxyphene.

Some preparations that contain dextropropoxyphene include: Distalgesic and Doloxene.

Indications

Analgesia

Dextropropoxyphene, like codeine, is a "weak" opioid. Codeine is more commonly used; however, some individuals (approximately 10-20% of the Caucasian population) are unable to metabolize it, due to poor functioning of the enzyme CYP2D6. It is in these people that dextropropoxyphene is particularly useful, as its metabolism does not require CYP2D6.

Restless Legs Syndrome

Propoxyphene has been found to be helpful in relieving the symptoms of Restless legs syndrome (RLS).

Opioid withdrawal

In pure form, dextropropoxyphene is commonly used to ease the withdrawal symptoms in people addicted to opioids. Being very weak in comparison to the opioids that are commonly abused, dextropropoxyphene can only act as a "partial" substitute. It does not have much effect on mental cravings; however it can be effective in alleviating physical withdrawal effects, such as muscle cramps.

Dextropropoxyphene is subject to some controversy: while many physicians prescribe it for a wide range of mildly to moderately painful symptoms as well as for treatment of diarrhea, many others refuse to prescribe it, citing its highly addictive nature and limited effectiveness.

The therapeutic index of dextroproxyphene is relatively small. In the UK, dextropropoxyphene and co-proxamol are now discouraged from general use; and, since 2004, preparations containing only dextropropoxyphene have been discontinued. This has been a somewhat controversial decision, since it has caused abusers to switch to the combined product and risk acetaminophen toxicity. Australia declined to follow suit and opted to allow pure dextropropoxyphene to remain available by prescription. From 31st December 2007, in the UK co-proxamol is only available on a named patient basis, for long term chronic pain and only to those who have already been prescribed this medicine. Its withdrawal from the UK market is a result of concerns relating to its toxicity on overdose (even small overdose can be fatal), and dangerous reaction with alcohol. Recreational use in the UK is uncommon. Many patients have been prescribed alternative combinations of more potent combinations.

In the United States, dextropropoxyphene HCl is available as a prescription formulation with acetaminophen aka paracetamol in ratio anywhere from 30mg / 600mg to 100mg / 650mg (or 100mg / 325mg in the case of Balacet), respectively. These are usually named "Darvocet." On the other hand, "Darvon" is a pure Propoxyphene preparation available in the U.S. that does not contain acetaminophen. In Australia, dextropropoxyphene is available on prescription, both as a combined product (32.5mg dextropropoxyphene per 325mg acetaminophen aka paracetamol branded as either "Di-gesic", "Capadex", and "Paradex," it is also availible in pure form (100mg capsules) known as "Doloxene".

Adverse effects

Darvocet overdose is commonly broken into two categories: liver toxicity (from acetaminophen poisoning) and dextropropoxyphene overdose. Many users experience toxic effects from the acetaminophen in pursuit of the endlessly-increasing dose required to achieve euphoria. They suffer acute liver toxicity, which causes severe stomach pains, nausea, and vomiting (all of which are increased by light or stimulation of the sense of sight).

Dextropropoxyphene also has several other non-opioid side-effects.

Both propoxyphene and its metabolite norpropoxyphene, have local anesthetic effects at concentrations about 10 times those necessary for opioid effects. In this respect, norpropoxyphene is more potent than propoxyphene, and they are both more potent than lidocaine.[2]

Both propoxyphene and norpropoxyphene also have direct cardiac effects which include decreased heart rate, decreased contractility, and decreased electrical conductivity (ie, increased PR, AH, HV, and QRS intervals). Norpropoxyphene is several times more potent than propoxyphene in this activity. These effects appear to be due to their local anesthetic activity and are not reversed by naloxone.[2][3][4]

Both propoxyphene and norpropoxyphene are potent blockers of cardiac membrane sodium channels and are more potent than lidocaine, quinidine, and procainamide in this respect.[5]

They (propoxyphene and nor-propoxyphene) appear to have the characteristics of a Vaughn Williams Class IC antiarrhythmic.

Darvon, a dextropropxyphene made by Eli Lilly, which had been on the market for 25 years, came under heavy fire in 1978 by consumer groups that said it was associated with suicide. Darvon was never withdrawn from the market, but Lilly has waged a sweeping, and largely successful, campaign among doctors, pharmacists and Darvon users to defend the drug as safe when it is used in proper doses and not mixed with alcohol.

In Sweden physicians have been discouraged by the medical products agency to prescribe dextropropoxyphene due to the risk of respiratory depression when taken with alcohol. [1] Products with other active ingredients have been taken off the market and only products with only dextropropoxyphene are supposed to be sold. Physicians are recommended only to prescribe products with only dextropropoxyphene and not to patients with a history of drug abuse, depression or suicidal tendencies. The combination of dextropropoxyphene HCL and acetaminophen sold under the name "Distalgesic" is no longer available in Sweden. Other products sold are "Doloxene" and "Dexofen" both containing Dextropropoxyphene napsylate.

In the United Kingdom, the Medicines & Healthcare Regulatory Authority (MHRA) removed the licence for Coproxamol on 31st December 2007. Whilst the MHRA are to be commended for their motivation in trying to reduce the number of suicides through missuse of Coproxamol, the decision has proven controversial reaching the rarefied heights of a UK Parliament House of Commons Adjournment Debate. Not once but twice. First on 13th July 2005: http://www.theyworkforyou.com/debates/?id=2005-07-13a.936.0 Then on 17th January 2007: http://www.theyworkforyou.com/whall/?id=2007-01-17b.340.0. The problem that has arisen is many patients have found alternatives to Coproxamol either too strong, too weak, or with intolerable side effects. During the House of Commons debates, it is quoted that originally some 1,700,000 patients in the UK were prescribed Coproxamol. Following the MHRA phased withdrawal this has eventually been reduced to 70,000. However, it appears this is the residual pool of patients who cannot find alternate analgesia to Coproxamol. To make matters worse, the MHRA safety net of prescribing Coproxamol after licence withdrawal from 31st December 2007 on a "Named Patient" basis where doctors agree there is a clinical need, has been rejected by most UK doctors because the MHRA wording that "responsibility will fall on the prescriber" is unacceptable to most doctors. As a result of many UK citizens now in untreated pain, there are now several patients lining up to launch a "Class Action" lawsuit against the MHRA: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/youropinions.php?opinionid=25173

Toxicologic Mechanism

A) Excessive opioid receptor stimulation is responsible for the CNS depression, respiratory depression, miosis, and gastrointestinal effects seen in propoxyphene poisoning. It may also account for mood/thought altering effects.

B) Local anesthetic activity appears to be responsible for the arrhythmias and cardiovascular depression seen in propoxyphene poisoning.[4] Widening of the QRS complex appears to be a result of a quinidine-like effect of propoxyphene, and sodium bicarbonate therapy appears to have a positive direct effect on the QRS dysrhythmia.[6]

C) Seizures may result from either opioid or local anesthetic effects.[2]

D) Pulmonary edema may result from direct pulmonary toxicity, neurogenic/anoxic effects, or cardiovascular depression.[4]

Recreational use

Those who take dextropropoxyphene for recreational purposes tend to take anywhere from 240 to 420 milligrams of dextropropoxyphene and, if it is not extracted, the acetaminophen aka paracetamol that is present in the preparation can be toxic. Some adverse effects of recreational dextropropoxyphene use are: a persistent dry mouth, decreased appetite, urinary retention and constipation that may lead to diverticulitis.

References

- ^ Slywka GW, Melikian AP, Whyatt PL, Meyer MC. "Propoxyphene bioavailability: an evaluation of ten products." Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 1975 Aug-Sep;15(8-9):598-604. PMID 12818953 Fulltext

- ^ a b c Nickander et al., 1984

- ^ Bredgaard, Sorensen et al., 1984

- ^ a b c Strom et al., 1985b

- ^ Holland & Steinberg, 1979

- ^ Stork et al., 1995