Chester

| Chester | |

|---|---|

A section of Bridge Street, part of Chester's commercial centre | |

| Population | 77,040 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SJ405665 |

| • London | 196 miles (315 km) SE |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CHESTER |

| Postcode district | CH1-4 |

| Dialling code | 01244 |

| Police | Cheshire |

| Fire | Cheshire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Chester (Template:Pron-en) is a city in Cheshire, England. Lying on the River Dee, close to the border with Wales, it is home to 77,040 inhabitants,[1] and is the largest and most populous settlement of the wider unitary authority area of Cheshire West and Chester, which had a population of 328,100 according to the 2001 Census.[2] Chester was granted city status in 1980.

Chester was founded as a "castrum" or Roman fort with the name Deva Victrix in the year 79 by the Roman Legio II Adiutrix during the reign of the Emperor Vespasian.[3] Chester's four main roads, Eastgate, Northgate, Watergate and Bridge, follow routes laid out at this time – almost 2,000 years ago. One of the three main Roman army bases, Deva later became a major settlement in the Roman province of Britannia. After the Romans left in the 5th century, the Saxons fortified the town against the Danes and gave Chester its name. The patron saint of Chester, Werburgh, is buried in Chester Cathedral.

Chester was one of the last towns in England to fall to the Normans in the Norman conquest of England. William the Conqueror ordered the construction of a castle, to dominate the town and the nearby Welsh border. In 1071[citation needed] he created Hugh d'Avranches, the 1st Earl of Chester.

Chester has a number of medieval buildings, but some of the black-and-white buildings within the city centre are actually Victorian restorations.[4] Chester is one of the best preserved walled cities in the British Isles. Apart from a 100 metres (330 ft) section, the listed Grade I walls are almost complete.[5]

The Industrial Revolution brought railways, canals, and new roads to the city, which saw substantial expansion and development – Chester Town Hall and the Grosvenor Museum are examples of Victorian architecture from this period.

History

Roman

The Romans founded Chester as Deva Victrix in the 70s AD in the land of the Celtic Cornovii, according to ancient cartographer Ptolemy,[6] as a fortress during the Roman expansion northward.[7] It was named Deva either after the goddess of the Dee,[8] or directly from the British name for the river.[9] The 'victrix' part of the name was taken from the title of the Legio XX Valeria Victrix which was based at Deva.[10] A civilian settlement grew around the military base, probably originating from trade with the fortress.[11] The fortress was 20% larger than other fortresses in Britannia built around the same time at York (Eboracum) and Caerleon (Isca Augusta);[12] this has led to the suggestion that the fortress, rather than London (Londinium), was intended to become the capital of the Roman province of Britannia Superior.[13] The civilian amphitheatre, which was built in the 1st century, could seat between 8,000 and 10,000 people.[14] It is the largest known military amphitheatre in Britain,[15] and is also a Scheduled Monument.[16] The Minerva Shrine in the Roman quarry is the only rock cut Roman shrine still in situ in Britain.[17] The fortress was garrisoned by the legion until at least the late 4th century.[18] Although the army had abandoned the fortress by 410 when the Romans retreated from Britannia,[19] the civilian settlement continued (probably with some Roman veterans staying behind with their wives and children) and its occupants probably continued to use the fortress and its defences as protection from raiders from the Irish Sea.[18]

Medieval

Deverdoeu was still one of two Welsh language names for Chester in the late 12th century; its other and more enduring Welsh name was 'Caerlleon', literally "the fortress-city of the legions", a name identical with that of the Roman fortress at the other end of the Welsh Marches at Caerleon in Monmouthshire, namely Isca Augusta. The colloquial modern Welsh name is the shortened form, Caer. The early Old English speaking Anglo Saxon settlers used a name which had the same meaning, Legacæstir, which was current until the 11th century, when, in a further parallel with Welsh usage, the first element fell out of use and the simplex name Chester emerged. From the 14th century to the 18th the city's prominent position in North West England meant that it was commonly also known as Westchester. This name was used by Celia Fiennes when she visited the city in 1698.[20]

Industrial history

Chester played a significant part in the Industrial Revolution which began in the North West of England in the latter part of the 18th century. The city village of Newtown, located north east of the city and bounded by the Shropshire Union Canal was at the very heart of this industry[citation needed] The large Chester Cattle Market and the two Chester railway stations, Chester General and Chester Northgate Station, meant that Newtown with its cattle market and canal, and Hoole with its railways were responsible for providing the vast majority of workers and in turn, the vast amount of Chester's wealth production throughout the Industrial Revolution.

Archaeology

Between 14 May 2007 and 6 July 2007, excavations were carried out in Grosvenor Park. The main aim was to find Cholmondeley's lost mansion, which was demolished in 1867.

A number of finds have come to light including:

- Plaster work from the mansion ceiling.

- Civil War musket balls

- Clay tobacco pipes (17th-18th century)

- Clay tobacco pipe waster clay from manufacture

- A base of a small Roman statue of Venus

- A Roman votive offering in the form of a lead axe head.[21][22][23]

Modern era

A considerable amount of land in Chester is owned by the Duke of Westminster who owns an estate, Eaton Hall, near the village of Eccleston. He also has London properties in Mayfair.

Grosvenor is the Duke's family name, which explains such features in the City such as the Grosvenor Bridge, the Grosvenor Hotel, and Grosvenor Park. Much of Chester's architecture dates from the Victorian era, many of the buildings being modelled on the Jacobean half-timbered style and designed by John Douglas, who was employed by the Duke as his principal architect. He had a trademark of twisted chimney stacks, many of which can be seen on the buildings in the city centre.

Douglas designed amongst other buildings the Grosvenor Hotel and the City Baths. In 1911, Douglas' protégé and city architect James Strong designed the then active fire station on the west side of Northgate Street. Another feature of all buildings belonging to the estate of Westminster is the 'Grey Diamonds' – a weaving pattern of grey bricks in the red brickwork laid out in a diamond formation.

Towards the end of WWII, a lack of affordable housing meant many problems for Chester. Large areas of farmland on the outskirts of the city were developed as residential areas in the 1950s and early 1960s producing, for instance, the suburb of Blacon. In 1964, a bypass was built through and around the town centre to combat traffic congestion.

These new developments caused local concern as the physicality and therefore the feel of the city was being dramatically altered. In 1968, a report by Donald Insall[24] in collaboration with authorities and government recommended that historic buildings be preserved in Chester. Consequently, the buildings were used in new and different ways instead of being flattened.[25]

In 1969 the City Conservation Area was designated. Over the next 20 years the emphasis was placed on saving historic buildings, such as The Falcon Inn, Dutch Houses and Kings Buildings.

On 13 January 2002, Chester was granted Fairtrade City status. This status was renewed by the Fairtrade Foundation on 20 August 2003.

Renaissance

In 2007 Chester Council announced a 10-year plan to see Chester become a "must see European destination". At a cost of £1.3 billion it has been nicknamed Chester Renaissance.[26] A website was launched by the Renaissance team, so that interested parties could monitor progress on all the projects.[27]

There are overall, seven developments ongoing in Chester.

The Northgate Development project began in 2007 with the demolition of St. Martin's House on the city's ring road. At a cost of £460 million, Chester City Council and developers ING hope to create a new quarter for Chester. The development will see the demolition of the market hall, bus station, theatre and NCP car park. In its place will be a new multi-storey car park, bus exchange, performing arts centre, library, homes, retail space and a department store which will be anchored by House of Fraser.[28]

On October 31, 2008, it was revealed that Chester's much heralded Northgate development was to be put on hold until 2012 due to the ongoing credit crunch.[29] However a number of Chester's other Renaissance projects continue at pace. The current active projects are; The Delamere Street development[30] and The £60million HQ development.[31]

Governance

Chester is an unparished area within the unitary authority of Cheshire West and Chester as of 1 April 2009 replacing the old Chester City Council and the local ward is the City ward electing 3 councillors. A small area around Chester Castle remains a civil parish of Chester Castle.[32] The Council was elected in May 2008 and the current councillors for the City Ward are Max E A Drury, Richard Lowe, and Tom Parry, all three representing the Conservative Party.[33] The Member of Parliament for the City of Chester is Christine Russell.[34]

Twin towns

Chester is twinned with

Geography

Chester lies at the southern end of a 2-mile (3.2 km) Triassic sandstone ridge that rises to a height of 42 m within a natural S-bend in the River Dee (before the course was altered in the 18th century). The bedrock, which is also known as the Chester Pebble Beds, is noticeable because of the many small stones trapped within its strata. Retreating glacial sheet ice also deposited quantities of sand and marl across the area where boulder clay was absent.

The eastern and northern part of Chester consisted of heathland and forest. The western side towards the Dee Estuary was marsh and wetland habitats.

Climate

As with most of the United Kingdom, Chester has an oceanic climate.

| Climate data for Chester | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: The Weather Channel[35] | |||||||||||||

Divisions and suburbs

Bache, Blacon, Boughton, Curzon Park, Great Boughton, Handbridge, Hoole, Huntington, Lache, Mollington, Newton, Newtown, Saltney, Saughall, Upton, Vicars Cross, Westminster Park

Demography

There are 77,040 living within the Greater Chester urban area (65% of the total of Chester District). This population is forecast to grow by 5% in the period 2005 to 2021.[1] The resident population for Chester District in the 2001 Census was 118,210. This represents 17.5% of the Cheshire County total (1.8% of the North West population).[2]

Economy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2008) |

The city's central shopping area includes its unique Rows or galleries (two levels of shops) which date from medieval times and are believed to include the oldest shop front in England.[36] The city has many chain stores, both in the centre and in retail parks to the west, and also features an indoor market, a department store (Browns of Chester, now absorbed by the Debenhams chain), and two main indoor shopping centres: The Grosvenor Mall and the Forum (a reference to the City's Roman past). The Forum, which houses stores and the Chester Market, will be demolished in the Northgate Development scheme to make way for new shopping streets, a new indoor market, an enlarged library, a car park and bus station, and a performing arts centre.[37]

Chester's main industries are now the service industries, comprising retail, tourism and financial services. Chester's main employer is Bank of America, formerly MBNA Europe. There are also several large financial firms including HBOS plc and M&S Money. At Ellesmere Port is a large Shell oil refinery. Just over the Welsh border to the west, near the village of Broughton, there is an Airbus UK factory (formerly British Aerospace), where the wings of Airbus aircraft, including the Airbus A380 are manufactured,[38] and there are food processing plants to the north and west. The Iceland frozen food company is based in nearby Deeside.

Chester has its own university, the University of Chester, and a major hospital, the Countess of Chester Hospital, named after Diana, Princess of Wales and Countess of Chester.

Transport

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2007) |

Canals

From about 1794 to the late 1950s, when the canal-side flour mills were closed, narrowboats carried cargo such as coal, slate, gypsum or lead ore as well as finished lead (for roofing, water pipes and sewerage) from the leadworks in Egerton Street (Newtown). Grain from Cheshire was stored in granaries on the banks of the canal at Newtown and Boughton and salt for preserving food arrived from Northwich.

The Chester Canal had locks down to the River Dee. Canal boats could enter the river at high tide to load goods directly onto seagoing vessels. The port facilities at Crane Wharf, by Chester racecourse, made an important contribution to the commercial development of the north-west region [citation needed].

The original Chester Canal was constructed to run from the River Dee near Sealand Road, to Nantwich in south Cheshire, and opened in 1774. In 1805, the Wirral section of the Ellesmere Canal was opened, which ran from Netherpool (now known as Ellesmere Port) to meet the Chester Canal at Chester canal basin. Later, those two canal branches became part of the Shropshire Union Canal network. This canal, which runs beneath the northern section of the city walls of Chester, is navigable and remains in use today.

Proposed canal

The original plan to complete the Ellesmere Canal was to connect Chester directly to the Wrexham coalfields by building a broad-gauge waterway with a branch to the River Dee at Holt. However with the advent of railways and high land prices, the plan was eventually abandoned in the mid 19th century. If the waterway had been built, canal traffic would have crossed the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct heading north to Chester and the River Dee.

As the route was never completed, the short length of canal north of Trevor, near Wrexham was infilled. The Llangollen Canal, although designed to be primarily a water source from the River Dee, became a cruising waterway despite its inherent narrow nature.

It would be rail that was to bring Welsh coal to Chester.

Railways

Chester formerly had two railway stations. Chester General railway station remains in use but Chester Northgate closed in 1969 as a result of the Beeching Axe.[39] Chester Northgate, which was located North East of the city centre, opened in 1875 as a terminus for the Cheshire Lines Committee. Trains travelled via Northwich to Manchester Central. Later services also went to Wrexham General via Shotton Station. It was demolished in the 1970s; the site is part of the Northgate Arena leisure centre.

Chester General, which opened in 1848, was designed with an Italianate frontage. It now has seven designated platforms but once had more. The station lost its original roof in the 1972 Chester General rail crash. In September 2007 extensive renovations took place to improve pedestrian access, and parking.[40] The present station has manned ticket offices and barriers, waiting rooms, toilets, shops and a pedestrian bridge with lifts. Chester General also had a large marshalling yard and engine sheds, most of which has now been replaced with housing.

Normal scheduled departures from Chester Station are: multiple services on the North Wales Coast Line; Virgin Trains to London Euston via Crewe; Arriva Trains Wales to Manchester Piccadilly via Warrington Bank Quay and Cardiff Central via Wrexham General; Northern Rail to Manchester Piccadilly via Northwich; Merseyrail to Liverpool on the Wirral Line.

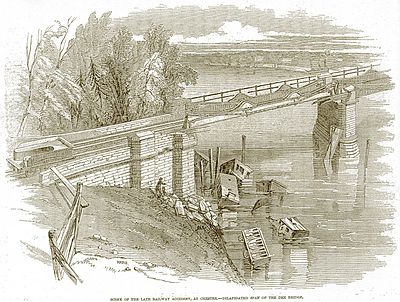

In late 1847 the Dee bridge disaster occurred when a bridge span collapsed as a train passed over the River Dee by the Roodee. Five people were killed in the accident. The bridge had been designed and built by famed-railway engineer Robert Stephenson for the Chester and Holyhead Railway. A Royal Commission inquiry found that the trusses were made of cast iron beams that had inadequate strength for their purpose. A national scandal ensued many new bridges of similar design were either taken down or heavily altered.

Trams

Chester had an extensive tram network during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It covered an area as far west as Saltney, on the Welsh border, to Chester General station, Tarvin Road and Great Boughton in the northwest. The network featured the narrowest gauge trams (3' 6") in mainland Britain, due to an act of Parliament which deemed that they must be the least obstructive possible.[citation needed]

The tramway was established in 1871 by Chester Tramways Corporation. It was horse-drawn until its electrification by overhead cables in 1903. The tramway was closed, like most others in the UK, in February 1930. All that remains are small areas of uncovered track inside the bus depot, and a few tram-wire supports attached to buildings on Eastgate/Foregate Street, although substantial sections of the track remain buried beneath the current road surface.

Roads

The city is a hub for major roads, including the M53 motorway towards the Wirral Peninsula and Liverpool and the M56 motorway towards Manchester. The A55 road runs along the North Wales coast to Holyhead and the A483 links the city to nearby Wrexham and Swansea to the far south.

Bus transport in the city is provided by First Group and Arriva, the council owned and operated ChesterBus (formerly Chester City Transport) having been sold to First Group in mid-2007. There are plans to build a new bus exchange in the city as well as a new coach station.

Cycling Demonstration Town

On June 19, 2008, then Transport Secretary Ruth Kelly named Chester as a Cycling Demonstration Town.[41] This initiative allows for substantial financial support to improve cycling facilities in the city, and a number of schemes are planned or already in development.[42]

Potential schemes include a new pedestrian and cycling bridge across the River Dee, linking the Meadows with Huntington and Great Boughton, an access route between Curzon Park and the Roodee, an extension to the existing greenway route from Hoole to Guilden Sutton and Mickle Trafford, and an access route between the Millennium cycle route and Deva Link.

Landmarks and tourist attractions

- See also Grade I listed buildings in Chester

The more unusual landmarks in the city are the city walls, the Rows and the black-and-white architecture. The walls encircle the bounds of the medieval city and constitute the most complete city walls in Britain,[5] the full circuit measuring nearly 2 miles (3 km).[43] The only break in the circuit is in the southwest section in front of County Hall.[44] A footpath runs along the top of the walls, crossing roads by bridges over Eastgate, Northgate, St Martin's Gate, Watergate, Bridgegate, Newgate, and the Wolf Gate, and passing a series of structures, namely Phoenix Tower (or King Charles' Tower), Morgan's Mount, the Goblin Tower (or Pemberton's Parlour), and Bonewaldesthorne's Tower with a spur leading to the Water Tower, and Thimbleby's Tower.[45] On Eastgate is Eastgate Clock which is said to be the most photographed clock in England after Big Ben.[46]

The Rows are unique in Britain.[47][48] They consist of buildings with shops or dwellings on the lowest two storeys. The shops or dwellings on the ground floor are often lower than the street and are entered by steps, which sometimes lead to a crypt-like vault. Those on the first floor are entered behind a continuous walkway, often with a sloping shelf between the walkway and the railings overlooking the street.[49] Much of the architecture of central Chester looks medieval and some of it is. But by far the greatest part of it, including most of the black-and-white buildings, is Victorian, a result of what Pevsner termed the "black-and-white revival".[50]

The most prominent buildings in the city centre are the town hall and the cathedral. The town hall was opened in 1869. It is in Gothic Revival style and has a tower and a short spire.[51] The cathedral was formerly the church of St Werburgh's Abbey. Its architecture dates back to the Norman era, with additions made most centuries since. A series of major restorations took place in the 19th century and in 1975 a separate bell tower was opened. The elaborately carved canopies of the choirstalls are considered to be one of the finest in the country. Also in the cathedral is the shrine of St Werburgh. To the north of the cathedral are the former monastic buildings.[52] The oldest church in the city is St John's, which is outside the city walls and was at one time the cathedral church. The church was shortened after the dissolution of the monasteries and ruins of the former east end remain outside the church. Much of the interior is in Norman style and this is considered to be the best example of 11th–12th century church architecture in Cheshire.[53] At the intersection of the former Roman roads is Chester Cross, to the north of which is the small church of St Peter’s which is in use as an ecumenical centre.[54] Other churches are now redundant and have other uses; St Michael’s in Bridge Street is a heritage centre,[55] St Mary-on-the-Hill is an educational centre,[56] and Holy Trinity now acts as the Guildhall.[57] Other notable buildings include the preserved shot tower, the highest structure in Chester.[58]

Roman remains can still be found in the city, particularly in the basements of some of the buildings and in the lower parts of the northern section of the city walls.[59] The most important Roman feature is the amphitheatre just outside the walls which is undergoing archaeological investigation.[60] Roman artifacts are on display in the Roman Gardens which run parallel to the city walls from Newgate to the River Dee, where there's also a reconstructed hypocaust system.[61] An original hypocaust system can be seen in the basement of the Spudulike restaurant on Bridge Street, which is open to the public.[62]

Of the medieval city the most important surviving structure is Chester Castle, particularly the Agricola Tower. Much of the rest of the castle has been replaced by the neoclassical county court and its entrance, the Propyleum.[63] To the south of the city runs the River Dee, with its 11th century weir. The river is crossed by the Old Dee Bridge, dating from the 13th century, the Grosvenor Bridge of 1832, and Queen's Park suspension bridge (for pedestrians).[64] To the southwest of the city the River Dee curves towards the north. The area between the river and the city walls here is known as the Roodee, and contains Chester Racecourse which holds a series of horse races and other events.[65] The Shropshire Union Canal runs to the north of the city and a branch leads from it to the River Dee.[66]

The major museum in Chester is the Grosvenor Museum which includes a collection of Roman tombstones and an art gallery. Associated with the museum is 20 Castle Street in which rooms are furnished in different historical styles.[67] The Dewa Roman Experience has hands-on exhibits and a reconstructed Roman street. And one of the blocks in the forecourt of the castle houses the Cheshire Military Museum.[68]

The major public park in Chester is Grosvenor Park.[69] On the south side of the River Dee, in Handbridge, is Edgar's Field, another public park,[70] which contains Minerva's Shrine, a Roman shrine to the goddess Minerva.[71] A war memorial to those who died in the world wars is in the town hall and it contains the names of all Chester servicemen who died in the First World War.[72]

Chester Visitor Centre, opposite the Roman Amphitheatre, issues a leaflet giving details of tourist attractions. Those not covered above include cruises on the River Dee and on the Shropshire Union Canal, and guided tours on an open-air bus.[73] The river cruises start from a riverside area known as the Groves, which contains seating and a bandstand.[74] A series of festivals is organised in the city, including mystery plays, a summer music festival and a literature festival.[75] Chester City Council has produced a series of leaflets for self-guided walks.[76] Tourist Information Centres are at the town hall and at Chester Visitor Centre.[77]

Culture

Arts and sport

In 2007, Chester's cultural sector was going through a major transformation. The Gateway Theatre had closed as part of the Northgate Development and so too had the Odeon cinema, which opened on 3 October 1936. The site was earmarked for redevelopment, with the closed Odeon cinema being the subject of a proposal to re-open it as part of an arts complex with a cinema at its heart; or its owners, Brook Leisure, may pursue planning permission to turn it into a nightclub.[78] Numerous public houses and wine bars, some of which date from medieval times, populate the city. Chester also has some nightclubs, which are soon going to be added to by the development of two new clubs in the next eighteen months.

Chester has its own film society, a number of successful amateur dramatic societies and theatre schools for youngsters.

To the east side of the city are the UK's largest zoological gardens, Chester Zoo.

Chester City football club don't currently play in a league. They were elected to the Football League in 1931, and have played at their Deva Stadium, straddling the England–Wales border, since 1992. The team was relegated out of the Football League in 2009 and went into administration. Notable former players include Ian Rush (who also managed the club), Cyrille Regis, Arthur Albiston, Earl Barrett, Lee Dixon, Steve Harkness, Roberto Martínez and Stan Pearson.

The city also has a professional basketball team in the national league, the BBL Championship. BiG Storage Cheshire Jets play at the city's Northgate Arena leisure centre; and a wheelchair basketball team, Celtic Warriors, formerly known as the Chester Wheelchair Jets.[79]

Chester Rugby Club (union) plays in the English National League 3 North. It won the EDF Energy Intermediate Cup in the 2007-08 season and has also won the Cheshire Cup several times.

There is a successful hockey club, Chester HC, who play at the County Officers' Club on Plas Newton Lane, and also an American Football team, the Chester Romans, part of the British American Football League.

Chester Racecourse hosts several flat race meetings from the spring to the autumn. The races take place within view of the City walls and attract tens of thousands of visitors. The May meeting includes several nationally significant races such as the Chester Vase, which is recognised as a trial for the Epsom Derby.

The River Dee is home to rowing clubs, notably Grosvenor Rowing Club and Royal Chester Rowing Club, as well as two school clubs, The King's School Chester Rowing Club and Queen's Park High Rowing Club. The weir is used by a number of local canoe and kayak clubs. Each July the Chester Raft Race is held on the River Dee in aid of charity. Chester Golf Club can also be found near the banks of the Dee.

Music

Chester has a brass band that was formed in 1853. It was known as the Blue Coat Band and today as The City of Chester Band.[80] It is a fourth section brass band with a training band. Its members wear a blue-jacketed uniform with an image of the Eastgate clock on the breast pocket of the blazer.

Chester Music Society was founded in 1948 as a small choral society. It now encompasses four sections: The Choir has 170 members drawn from Chester and the surrounding district; The Youth Choirs support three choirs: Youth Choir, Preludes, and the Alumni Choir; Celebrity Concerts promote a season of six high quality concerts each year; The Club is a long established section which aims to encourage young musicians and in many cases offers the first opportunity to perform in public.

Pop band Mansun are probably the most famous Britpop band to come from Chester.

Media

Chester's newspapers are the daily Chester Evening Leader, and the weekly Chester Chronicle. It also has free publications, such as the newspapers Midweek Chronicle and Chester Standard and the free student magazine Wireless. Dee 106.3 is the city's radio station, with Heart Wrexham and BBC Radio Merseyside also broadcasting locally. Chester is where Channel 4's soap-opera Hollyoaks is set (although most filming takes place around Liverpool).

Notable people

- Anthony Thwaite (born 1930), poet and writer.[81]

- The grammarian and lexicographer A. S. Hornby (1898–1978) was also born in the city.[82]

- Randolph Caldecott (1846–86), artist and book illustrator, was born in Bridge Street, Chester.

- The conductor Sir Adrian Boult (1889–1983), was born in Liverpool Road.[83]

- Beatrice Tinsley (née Hill) (1941–1981), astronomer and cosmologist, professor of astronomy at Yale University was also born in the city but was brought up in New Zealand.[84]

- David Roberts (1859–1928) the engineer who invented the caterpillar track, grew up in Great Boughton.[citation needed]

- L. T. C. Rolt (1910–74), engineering historian was born in Chester,[85]

- James Hamilton, author of children's books.[86]

- Steve Wright, singer of Juveniles, Fiat Lux, Camera Obscura and Hoi Poloi.[87]

- Leonard Cheshire renowned Second World War RAF Pilot and founder of the Leonard Cheshire Disability charity was born in Hoole Road, Hoole, Chester (although he was brought up in Oxford). The house where he was born (now a guest house ) bears a plaque attesting to this.

Actors

- Basil Radford (1897–1952).[88]

- Hugh Lloyd (born 1923).[89]

- Ronald Pickup (born 1940).[90]

- Daniel Craig (born 1968).[91]

- Emily Booth (born 1976), actress and writer.[92]

Comedians

- Russ Abbot (born 1947) (birth name Russell A. Roberts), musician, comedian and actor.[93]

- Jeff Green (born 1964), comedian.[94]

- Bob Mills (born 1957), comedian and gameshow host.

Sport

- Fulham F.C. and English football international Danny Murphy (born 1977).[95]

- Manchester United and English football international Michael Owen (born 1979).[96]

- St. Mirren F.C. footballer Andy Dorman (born 1982).[97] and

- Manchester United goalkeeper Tom Heaton (born 1986).[98]

- Sunderland A.F.C. footballer Danny Collins (born 1980).[99]

- Stoke City F.C. footballer Ryan Shawcross (born 1987).[100]

- International rugby union footballers and brothers Pat Sanderson (born 1977).[101]

- Ricky Walden professional snooker player (born 1982).[102]

- Alex Sanderson (born 1979).[103]

- Helen Willetts (born 1972), former badminton international and weather forecaster.[104]

- Ben Foden rugby player England and Northampton saints (born 1985)[105]

Musicians

- Composer Philip Venables.[106]

- Composer Howard Skempton.[107]

Curators

In Popular Culture

- The Roman settlement of Deva is the setting of Ruth Downie's Roman era mystery, Medicus.

- Chester is the Setting of Channel 4's Teen Soap Hollyoaks however it is filmed mostly in Liverpool.

See also

- Grade I listed buildings in Chester

- St Paul's Church, Boughton

- St Barnabas' Church, Chester

- St Mary's Church, Handbridge

- All Saints Church, Hoole

- Newtown, Chester

References

Notes

- ^ a b c "Demographics" (PDF). Cheshire County Council. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ a b "2001 Census: Census Area Statistics Chester (Local Authority)". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 27 September 2008. Also: "Chester in context". Chester City Council. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- ^ The Times Online - "Torture topped the bill in Roman Chester" by Dalya Alberge, February 17, 2007

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Morriss, p. 43.

- ^ Ptolemy (1992), Book II Chapter 2

- ^ Mason (2001), p. 42.

- ^ Salway, P. (1993) The Oxford Illustrated History of Roman Britain. ISBN CN 1634

- ^ C.P. Lewis, A.T. Thacker (Editors) (2003). "A History of the County of Chester: Volume 5 part 1". British-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Mason (2001), p. 128.

- ^ Mason (2001), p. 101.

- ^ Carrington (2002), p. 33-35.

- ^ Carrington (2002), p. 46.

- ^ Spicer, Graham (9 January 2007). "Revealed: New discoveries at Chester's Roman amphitheatre". Culture24.org.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ Carrington (2002), p. 54-56.

- ^ "Chester Amphitheatre". Pastscape.org.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- ^ "Roman shrine to Minerva". Images of England. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ a b Lewis, C.P. (2003). "Roman Chester". A History of the County of Chester: Volume 5 part 1: the City of Chester: General History and Topography. British-History.ac.uk: 9–15. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Mason (2001), p. 209-210.

- ^ "The Illustrated Journeys of Celia Fiennes 1685 - c1712" edited by Christopher Morris

- ^ The Past Uncovered. Chester Archaeology Newsletter. February 2007. ISSN 1364-324x

- ^ The Past Uncovered. Chester Archaeology Newsletter. June 2007. ISSN 1364-324x

- ^ "Archaeology in the park" (PDF). Chester City Council. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Donald Insall Associates, official website". Retrieved 21 November 2007.

- ^ "Chester Travel Guide and Travel Information". Lonely Planet.

- ^ "Chester Renaissance". Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ http://www.chesterrenaissance.co.uk/

- ^ "Northgate Development News". Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ http://www.chesterchronicle.co.uk/chester-news/local-chester-news/2008/10/31/chester-s-460m-northgate-scheme-on-hold-until-2012-59067-22157727/

- ^ http://www.chesterrenaissance.co.uk/delamere.htm

- ^ http://www.robinsons.com/editorials.asp?c=69&d=4

- ^ "Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Bill". United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 9 August 2007.

- ^ http://cmttpublic.cheshirewestandchester.gov.uk/mgMemberIndex.asp?FN=WARD&VW=LIST&PIC=0&J=1 Cheshire West & Chester Council Membership

- ^ http://www.theyworkforyou.com/mp/christine_russell/chester,_city_of Chester, City of (TheyWorkForYou.com)

- ^ Monthly averages for Chester, United Kingdom The Weather Channel Retrieved 4 March 2009

- ^ "Visit Chester & Cheshire 2009 Visitor Guide" (Press release). Experience Northwest England. 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2009.

- ^ Chester Northgate Project Chester Renaissance, accessed April 11, 2009

- ^ "A380 wings roll off production line at Airbus Broughton". BBC News. Monday, 5 April 2004. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Richard Beeching's report "The Reshaping of British Railways" was published in 1965.

- ^ Chester Railway Renovation Chester Renaissance, accessed April 11, 2009

- ^ "CycleEngland". Cycle England. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "CYCLEChester". CYCLEChester. Retrieved 9 July 2009.> Also:"Chester Cycle City". Chester Cycle city. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ Bilsborough, p. 9.

- ^ "Chester Walls South West Section". Chester City Council. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 154–156.

- ^ "Information Sheet: Eastgate Clock". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Bilsborough, p. 17.

- ^ Ward, p. 50.

- ^ Morriss, pp. 13–14

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 38–39, 130–131.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, p. 158.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 135–147

- ^ "Images of England: Church of St John the Baptist, Chester". English Heritage. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "St. Peter's Ecumenical Centre". Parish of Chester. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Images of England: Heritage centre". English Heritage. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ "Images of England: St Mary's Centre". English Heritage. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 152–153

- ^ "Chester Lead Works" (PDF). Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 133–134

- ^ "Amphitheatre Project". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Roman Gardens". Chester City Council. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ^ "English Heritage Spud-U-Like entry". The Civic Trust. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ^ "Information Sheet: Chester Castle". Chester City Council. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ^ Pevsner and Hubbard, pp. 159–160

- ^ "Chester Racecourse". Chester Racecourse. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Canal Towpath Trail" (PDF). Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "The Grosvenor Museum". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Cheshire Military Museum". University of Chester. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Grosvenor Park". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Discover Edgar's Field". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Minerva's Shrine". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "War Memorial, Town Hall, Chester, Cheshire". Carl's Cam. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Chester Attractions" (PDF). Chester Visitor Centre. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Recreation and Leisure". Chester City Council. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ^ "Festivals and Events". Chester City Council. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ "Heritage Trails". Chester City Council. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ^ "Tourist Information Centre". Chester City Council. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ^ "Russell confident of winning Odeon fight". Chester Chronicle. 10 August 2007. Retrieved 10 August 2007.

- ^ "Chester Wheelchair Jets website". Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "City of Chester Band website". Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- ^ "Anthony Thwaite". British Council. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ Cowie, A. P. (2004) 'Hornby, Albert Sidney (1898-1978)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press [1], Retrieved on 20 April 2008.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (2004) 'Boult, Sir Adrian Cedric (1889-1983)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press [2], Retrieved on 20 April 2008

- ^ "Beatrice Tinsley: Queen of the Cosmos". NZEdge.com. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ Buchanan, R. Angus (2004) 'Rolt, (Lionel) Thomas Caswall (1910-1974)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press [3], Retrieved on 23 April 2008.

- ^ 'Caldecott , Randolph (1846-86)', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press [4], Retrieved on 20 April 2008.

- ^ [5]

- ^ "Basil Radford". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Hugh Lloyd". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Ronald Pickup". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Craig, Daniel". British Film Institute. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Emily Booth". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Biography for Russ Abbot". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Your questions for Jeff Green". BBC. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Murphy". Football Database. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Michael Owen". TheFA.com. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Andy Dorman". Football.co.uk. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Tom Heaton". Manchester United F.C. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- ^ "Danny Collins player profile".

- ^ "Player profile for Ryan Shawcross".

- ^ "Pat Sanderson England Profile". England Rugby. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ http://www.rickywalden.co.uk/viewpage.php?page_id=2

- ^ "Biography for Alex Sanderson". The Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ "Helen Willetts". BBC. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- ^ http://www.rbs6nations.com/en/rugbyforce.php

- ^ "Philip Venables' website".

- ^ "Howard Skempton's entry on the OUP website".

Bibliography

- Bilsborough, Norman (1983). The Treasures of Cheshire. Swinton: North West Civic Trust. ISBN 0 901 347 35 3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Carrington, P (ed.) (2002). Deva Victrix: Roman Chester Re-assessed. Chester: Chester Archaeological Society. ISBN 095070749X.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Emery, G (1998). Chester inside out. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265928.

- Emery, G (1999). Curious Chester: Portrait of an English city over two thousand years. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265944.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Emery, G (2002). Chester electric lighting station: From steam and hydro–The illuminating story of Chester streetlighting and Britain's first rural electricity supply. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265480.

- Emery, G (2003). The Chester guide: England's walled city, Roman remains, museums, attractions, River Dee, shopping on the medieval rows, cathedral, access. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265898.

- Emery, G (1999). The old Chester canal: A History and Guide. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Lewis, P.R. (2007). Disaster on the Dee: Robert Stephenson's Nemesis of 1847. Stroud, United Kingdom: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 9780752442662.

- Marshall, A. E. (1966). Myths and Legends of Chester. Chester, United Kingdom: Chester blind welfare society. ISBN 095117830X.

- Mason, David J.P. (2001). Roman Chester: City of the Eagles. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7524-1922-6.

- Morriss, Richard K. (1993). The Buildings of Chester. Stroud: Alan Sutton. ISBN 0-7509-0255-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Morton, H. V. (1930). In Search of England. London: Methuen.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (2003) [1971]. The Buildings of England: Cheshire. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0 300 09588 0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Place, G.W. (1994). The Rise and Fall of Parkgate, Passenger Port for Ireland, 1686-1815 (Chetham Society). Lancaster, United Kingdom: Carnegie Publishing Limited. ISBN 1859360238.

- Ptolemy (1992). The Geography. Dover Publications Inc. ISBN 0486268969.

- Wall, B. (1992). Tales of Chester. Shropshire, United Kingdom: S. B. Publications. ISBN 1857700066.

- Ward, Simon (2009). Chester: A History. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978 1 86077 499 7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Wilding, R. (1997). Miller of Dee:The story of Chester mills and millers, their trades, and wares, the weir, the water engine, and the salmon. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265952.

- Wilding, R. (2003). Death in Chester: Roman Gravestones, Cathedral Burials, Martyrs, Witches, the Plague, Horrible Hangings, Gruesome Deaths and Ghostly Goings-on. Chester, United Kingdom: Gordon Emery. ISBN 1872265448.