Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 | |

| Vice President | Aaron Burr George Clinton |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| 2nd Vice President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | Aaron Burr |

| 1st United States Secretary of State | |

| In office March 22, 1790 – December 31, 1793 | |

| President | George Washington |

| Preceded by | John Jay (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Edmund Randolph |

| United States Minister to France | |

| In office May 17, 1785 – September 26, 1789 | |

| Appointed by | Congress of the Confederation |

| Preceded by | Benjamin Franklin |

| Succeeded by | William Short |

| Delegate to the Congress of the Confederation from Virginia | |

| In office November 3, 1783 – May 7, 1784 | |

| Preceded by | James Madison |

| Succeeded by | Richard Henry Lee |

| 2nd Governor of Virginia | |

| In office June 1, 1779 – June 3, 1781 | |

| Preceded by | Patrick Henry |

| Succeeded by | William Fleming |

| Delegate to the Second Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office June 20, 1775 – September 26, 1776 | |

| Preceded by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | John Harvie |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 13, 1743 Shadwell, Colony of Virginia |

| Died | July 4, 1826 (aged 83) Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican |

| Spouse | Martha Wayles |

| Children | Martha Jane Mary Lucy Lucy Elizabeth |

| Residence(s) | Monticello Poplar Forest |

| Alma mater | College of William and Mary |

| Profession | Planter Lawyer College Administrator |

| Signature | |

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 (April 2, 1743 O.S.) – July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Father who was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence (1776) and the third President of the United States (1801–1809). At the beginning of the American Revolution, Jefferson served in the Continental Congress, representing Virginia. He then served as a wartime Governor of Virginia (1779–1781). Just after the war ended, from mid-1784 Jefferson served as a diplomat, stationed in Paris, initially as a commissioner to help negotiate commercial treaties. In May 1785, he became the United States Minister to France. He was the first United States Secretary of State (1790–1793) during the administration of President George Washington. Upon resigning his office, with his close friend James Madison he organized the Democratic-Republican Party. Elected Vice-President in 1796, under his opponent John Adams, Jefferson with Madison secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which attempted to nullify the Alien and Sedition Acts and formed the basis of states' rights.

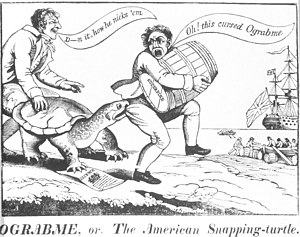

Elected president in what Jefferson called the Revolution of 1800, he oversaw a peaceful transition in power, purchased the vast Louisiana Territory from France (1803), and sent the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804–1806) to explore the new west. His second term was beset with troubles at home, such as the failed treason trial of his former Vice President Aaron Burr, and escalating trouble with Britain. With Britain at war with Napoleon, he tried aggressive economic warfare against them; however, his embargo laws did more damage to American trade and the economy, and provoked a furious reaction in the Northeast. Jefferson has often been rated in scholarly surveys as one of the greatest U.S. presidents, though since the mid-twentieth century, some historians have increasingly criticized him for his failure to act against domestic slavery.[1][2]

A leader in the Enlightenment, Jefferson was a polymath who spoke five languages and was deeply interested in science, invention, architecture, religion and philosophy. He designed his own large mansion on a 5,000 acre plantation near Charlottesville, Virginia, which he named Monticello. His interests led him to assist in founding the University of Virginia in his post-presidency years. While not an orator, he was an indefatigable letter writer and corresponded with many influential people in America and Europe. As part of the Virginia planter elite and, as a tobacco planter, Jefferson owned hundreds of slaves throughout his lifetime. Like many of his contemporaries, he viewed Africans as being racially inferior. His views on slavery were complex, and changed over the course of his life. He was a leading American opponent of the international slave trade, and signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves on March 2, 1807.

After Martha Jefferson, his wife of eleven years, died in 1782, Thomas remained a widower for the rest of his life; his marriage produced six children, with only two surviving to adulthood. In 1802 allegations surfaced that he was also the father of his house slave Sally Hemings' children. In 1998, DNA tests revealed a match between her last child and the Jefferson male family line. Whether these children were fathered by Jefferson himself, or one of his relatives, remains a matter of debate among historians.

Early life and career

The third of ten children, Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743 (April 2, 1743 O.S.)[Note 1] at the family home in Shadwell, Goochland County, Virginia, now part of Albemarle County.[3] His father was Peter Jefferson, a planter and slaveholder, and a surveyor.[4] He was of possible Welsh descent, although this remains unclear.[5] His mother was Jane Randolph, daughter of Isham Randolph, a ship's captain and sometime planter. Peter and Jane married in 1739.[6] Thomas Jefferson was little interested and indifferent to his ancestry and he only knew of the existence of his paternal grandfather.[5]

Before the widower William Randolph, an old friend of Peter Jefferson, died in 1745, he appointed Peter as guardian to manage his Tuckahoe Plantation and care for his four children. That year the Jeffersons relocated to Tuckahoe, where they lived for the next seven years before returning to Shadwell in 1752. Here Thomas Jefferson recorded his earliest memory, that of being carried on a pillow by a slave during the move to Tuckahoe.[7] Peter Jefferson died in 1757 and the Jefferson estate was divided between Peter's two sons; Thomas and Randolph.[8] Thomas inherited approximately 5,000 acres (2,000 ha; 7.8 sq mi) of land, including Monticello and between 20-40 slaves. He took control of the property after he came of age at 21.[9]

On October 1, 1765, when Jefferson was 22, his oldest sister Jane died at the age of 25.[10] He fell into a period of deep mourning, as he was already saddened by the absence of his sisters Mary, who had been married several years to Thomas Bolling, and Martha, who in July had wed Dabney Carr.[10] Both lived at their husbands' residences. Only Jefferson's younger siblings Elizabeth, Lucy, and the two toddlers, were at home. He drew little comfort from the younger ones, as they did not provide him with the same intellectual engagement as the older sisters had.[10] According to the historian Ferling, while growing up Jefferson struggled with loneliness and abandonment issues that eventually developed into a reclusive lifestyle as an adult.[11]

Education

Jefferson began his childhood education under the direction of tutors at Tuckahoe along with the Randolph children.[12]

In 1752, Jefferson began attending a local school run by a Scottish Presbyterian minister. At the age of nine, Jefferson began studying Latin, Greek, and French; he learned to ride horses, and began to appreciate the study of nature. He studied under the Reverend James Maury from 1758 to 1760 near Gordonsville, Virginia. While boarding with Maury's family, he studied history, science and the classics.[13]

At age 16, Jefferson entered the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, and first met the law professor George Wythe, who became his influential mentor. For two years he studied mathematics, metaphysics, and philosophy under Professor William Small, who introduced the enthusiastic Jefferson to the writings of the British Empiricists, including John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton.[14] He also improved his French, Greek, and violin. A diligent student, Jefferson displayed an avid curiosity in all fields[15] and graduated in 1762 with highest honors.[citation needed] Jefferson read law while working as a law clerk for Wythe. During this time, he also read a wide variety of English classics and political works. Jefferson was admitted to the Virginia bar five years later in 1767.[16]

Throughout his life, Jefferson depended on books for his education. He collected and accumulated thousands of books for his library at Monticello. When Jefferson's father Peter died Thomas inherited, among other things, his large library. [17] A significant portion of Jefferson's library was also bequeathed to him in the will of George Wythe, who had an extensive collection. Always eager for more knowledge, Jefferson continued learning throughout most of his life. Jefferson once said, "I cannot live without books."[18]

Marriage and family

After practicing as a circuit lawyer for several years,[19] Jefferson married the 23-year-old widow Martha Wayles Skelton. The wedding was celebrated on January 1, 1772 at Martha's home, an estate called 'The Forest' near Williamsburg, Virginia.[20] Martha Jefferson was described as attractive, gracious and popular with their friends; she was a frequent hostess for Jefferson and managed the large household. They were said to have a happy marriage. She read widely, did fine needle work and was an amateur musician. Jefferson played the violin and Martha was an accomplished piano player. It is said that she was attracted to Thomas largely because of their mutual love of music.[20][21] One of the wedding gifts he gave to Martha was a "forte-piano".[22] During the ten years of their marriage, she had six children: Martha Washington, called Patsy, (1772–1836); Jane (1774–1775); a stillborn or unnamed son in 1777; Mary Wayles (1778–1804), called Polly; Lucy Elizabeth (1780–1781); and Lucy Elizabeth (1782–1785). Two survived to adulthood.[22]

After her father John Wayles died in 1773, Martha and her husband Jefferson inherited his 135 slaves, 11,000 acres and the debts of his estate. These took Jefferson and other co-executors of the estate years to pay off, which contributed to his financial problems. Among the slaves were Betty Hemings and her 10 children; the six youngest were half-siblings of Martha Wayles Jefferson, as they are believed to have been children of her father,[Note 2] and they were three-quarters European in ancestry. The youngest, an infant, was Sally Hemings. As they grew and were trained, all the Hemings family members were assigned to privileged positions among the slaves at Monticello, as domestic servants, chefs, and highly skilled artisans.[23]

Later in life, Martha Jefferson suffered from diabetes and ill health, and frequent childbirth further weakened her. A few months after the birth of her last child, Martha died on September 6, 1782. Jefferson was at his wife's bedside and was distraught after her death. In the following three weeks, Jefferson shut himself in his room, where he paced back and forth until he was nearly exhausted. Later he would often take long rides on secluded roads to mourn for his wife.[21][22] As he had promised his wife, Jefferson never remarried.

Jefferson's oldest daughter Martha (called Patsy) married Thomas Mann Randolph, Jr. in 1790. They had 12 children, eleven of whom survived to adulthood. She suffered severe problems as Randolph became alcoholic and was abusive. When they separated for several years, Martha and her many children lived at Monticello with her father, adding to his financial burdens. Her oldest son, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, helped her run Monticello for a time after her father's death. She had the longest life of Jefferson's children by Martha.[22]

Mary Jefferson (called Polly and Maria) married her first cousin John Wayles Eppes in 1797. As a wedding settlement, Jefferson gave them Betsy Hemmings, the 14-year-old granddaughter of Betty Hemings, and 30 other slaves.[24] The Eppes had three children together, but only a son survived. Frail like her mother, Maria died at the age of 25, several months after her third child was born. It also died, and only her son Francis W. Eppes survived to adulthood, cared for by slaves, his father and, after five years, a stepmother.[24][25]

Monticello

In 1768 Jefferson started the construction of Monticello, a neoclassical mansion on 5,000 acres which he designed himself. Since childhood, Jefferson had always wanted to build a mountaintop home within sight of his former home of Shadwell.[26][27] Jefferson moved into the South Pavilion (an outbuilding) in 1770, where his new wife Martha joined him in 1772. Monticello would be his continuing project to create a neoclassical environment, based on his study of the architect Andrea Palladio and the classical orders.[28]

While Minister to France during 1784–1789, he had an opportunity to see some of the classical buildings with which he had become acquainted from his reading, as well as to discover the "modern" trends in French architecture then fashionable in Paris. In 1794, following his service as Secretary of State (1790–93), he began rebuilding Monticello based on the ideas he had acquired in Europe. The remodeling continued throughout most of his presidency (1801–09).[29] The most notable change was the addition of the octagonal dome.[30]

Lawyer and House of Burgesses

Jefferson handled many cases as a lawyer in colonial Virginia, and was very active from 1768 to 1773.[31] Jefferson's client list included members of the Virginia's elite families, including members of his mother's family, the Randolphs.[31]

Beside practicing law, Jefferson represented Albemarle County in the Virginia House of Burgesses beginning on May 11, 1769 and ending June 20, 1775.[32] His friend and mentor George Wythe served at the same time. Following the passage of the Coercive Acts by the British Parliament in 1774, Jefferson wrote a set of resolutions against the acts, which were expanded into A Summary View of the Rights of British America, his first published work. Previous criticism of the Coercive Acts had focused on legal and constitutional issues, but Jefferson offered the radical notion that the colonists had the natural right to govern themselves.[33] Jefferson argued that Parliament was the legislature of Great Britain only, and had no legislative authority in the colonies. The paper was intended to serve as instructions for the Virginia delegation of the First Continental Congress, but Jefferson's ideas proved to be too radical for that body.[citation needed]

Political career from 1775 to 1800

Declaration of Independence

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, a formal document which officially proclaimed the dissolution of the American colonies from the British Crown. The sentiments of revolution put forth in the Declaration were already well established in 1776 as the colonies were already at war with the British when the Declaration was being debated, drafted and signed. [34] [35]

Before the Declaration was drafted Jefferson served as a delegate from Virginia to the Second Continental Congress beginning in June 1775, soon after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War. He sought out John Adams who, along with his cousin Samuel, had emerged as a leader of the convention.[36] Jefferson and Adams established a lifelong friendship and would correspond frequently; Adams ensured that Jefferson was appointed to the five-man committee to write a declaration in support of the resolution of independence.[37] Having agreed on an approach, the committee selected Jefferson to write the first draft. His eloquent writing style made him the committee's choice for primary author; the others edited his draft.[38][39] During June 1776, the month before the signing, Jefferson took notes of the Congressional debates over the proposed Declaration in order to include such sentiments in his draft, among other things justifying the right of citizens to resort to revolution.[40] Jefferson also drew from his proposed draft of the Virginia Constitution, George Mason's draft of the Virginia Declaration of Rights, and other sources.

The historian Joseph Ellis states that the Declaration was the "core of [Jefferson]'s seductive appeal across the ages".[41] After working for two days to modify the document, Congress removed language that was deemed antagonistic to friends in Britain and Jefferson's clause that indicted the British monarchy for imposing African slavery on the colonies. This was the longest clause removed.[40] Congress trimmed the draft by about one fourth, wanting the Declaration to appeal to the population in Great Britain as well as the soon to be United States, while at the same time not wanting to give South Carolina and Georgia reasons to oppose the Declaration on abolitionist grounds. Jefferson deeply resented some of the many omissions Congress made.[40][42] On July 4, 1776, Congress ratified the Declaration of Independence and distributed the document.[43] Historians have considered it to be one of Jefferson's major achievements; the preamble is considered an enduring statement of human rights that has inspired people around the world.[44] Its second sentence is the following:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

This has been called "one of the best-known sentences in the English language",[45] containing "the most potent and consequential words in American history".[46] The passage came to represent a moral standard to which the United States should strive. This view was notably promoted by Abraham Lincoln, who based his philosophy on it, and argued for the Declaration as a statement of principles through which the United States Constitution should be interpreted.[47] Intended also as a revolutionary document for the world, not just the colonies, the Declaration of Independence was Jefferson's assertion of his core beliefs in a republican form of government.[40] The Declaration became the core document and a tradition in American political values. It also became the model of democracy that was adopted by many peoples around the world, including South Africa, the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union and other modern day contemporaries trying to advance the ideas of individual freedom and democracy for their countries. Abraham Lincoln once referred to Jefferson's principles as "..the definitions and axioms of a free society..". [48]

Virginia state legislator and Governor

This article contains close paraphrasing of non-free copyrighted sources. (January 2012) |

After Independence, Jefferson desired to reform the Virginia government.[49] In September 1776, eager to work on creating the new government and dismantle the feudal aspects of the old, Jefferson returned to Virginia and was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates for Albemarle County.[50] Before his return, he had contributed to the state's constitution from Philadelphia; he continued to support freehold suffrage, by which only property holders could vote.[51]. Jefferson attempted to establish himself as a foe of slavery during the Revolution, however, the 21st century historian John Ferling has called this mostly "hyperbole".[49]

He served as a Delegate from September 26, 1776 – June 1, 1779, as the war continued. Jefferson worked on Revision of Laws to reflect Virginia's new status as a democratic state. By abolishing primogeniture, establishing freedom of religion, and providing for general education, he hoped to make the basis of "republican government." [51] Ending the Anglican Church as the state (or established) religion was a first step. Jefferson introduced his "Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom" in 1779, but it was not enacted until 1786, while he was in France as US Minister.[52]

In 1778 Jefferson supported a bill to prohibit the international slave trade in Virginia; the state was the first in the union to adopt such legislation. This was significant as the slave trade would be protected from regulation for 20 years at the federal level under the new Constitution in 1787. Abolitionists in Virginia expected the new law to be followed by gradual emancipation, as Jefferson had supported this by opinion, but he discouraged such action while in the Assembly. Following his departure, the Assembly passed a law in 1782 making manumission easier. As a result, the number of free blacks in Virginia rose markedly by 1810: from 1800 in 1782 to 12,766 in 1790, and to 30,570 by 1810, when they formed 8.2 percent of the black population in the state.[53]

He drafted 126 bills in three years, including laws to establish fee simple tenure in land, which removed inheritance strictures, and to streamline the judicial system. In 1778, Jefferson's "Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge" and subsequent efforts to reduce control by clergy led to some small changes at William and Mary College, but free public education was not established until the late nineteenth century after the Civil War.[54] Jefferson proposed a bill to eliminate capital punishment in Virginia for all crimes except murder and treason, but his effort was defeated.[55] In 1779, at Jefferson's behest, William and Mary appointed his mentor George Wythe as the first professor of law in an American university.[56]

In 1779, at the age of thirty-six, Jefferson was elected Governor of Virginia by the two houses of the legislature, as was the process.[57] The term was then for one year, and he was re-elected in 1780. As governor in 1780, he transferred the state capital from Williamsburg to Richmond.

He served as a wartime governor, as the united colonies continued the Revolutionary War against Great Britain. By this time, Georgia had fallen to the British, whose forces had invaded South Carolina and threatened Charleston.[citation needed] In late 1780, Governor Jefferson prepared Richmond for attack by moving all arms, military supplies and records to a foundry located five miles outside of town. General Benedict Arnold, who had switched to the British side in 1780, learned of the transfer and moved to capture the foundry. Jefferson tried to get the supplies moved to Westham, seven miles to the north, but he was too late. He also delayed too long in raising a militia.

Arnold's troops burned the foundry before returning to Richmond, where they burned much of the city the following morning.[58] With the Assembly, Jefferson evacuated the government in January 1781 from Richmond to Charlottesville. They began to meet at his home of Monticello. The government had moved so rapidly that he left his household slaves in Richmond, where they were captured as prisoners of war by the British and later exchanged for soldiers. In January 1781, Benedict Arnold led an armada of British ships and, with 1600 British regulars, conducted raids along the James River. Later Arnold would join Lord Cornwallis, whose troops were marching across Virginia from the south.

In early June 1781, Cornwallis dispatched a 250-man cavalry force commanded by Banastre Tarleton on a secret expedition to capture Governor Jefferson and members of the Assembly at Monticello.[57] Tarleton hoped to surprise Jefferson, but Jack Jouett, a captain in the Virginia militia, thwarted the British plan by warning the governor and members of the Assembly.[59] Jefferson and his family escaped and fled to Poplar Forest, his plantation to the west. Tarleton did not allow looting or destruction at Monticello by his troops.

By contrast, when Lord Cornwallis and his sizeable number of troops later occupied Elkhill, a smaller estate of Jefferson's on the James River in Goochland County, they stripped it of resources and left it in ruins. According to a letter by Jefferson about Elkhill, British troops destroyed all his crops, burned his barns and fences, slaughtered or drove off the livestock, seized usable horses, cut the throats of foals and, after setting fires, left the plantation a waste. They captured 27 slaves and held them as prisoners of war. At least 24 died in the camp of diseases,[60] a chronic problem for prisoners and troops in an era of poor sanitation.

Jefferson believed his gubernatorial term had expired in June, and he spent much of the summer with his family at Poplar Forest.[59] The members of the General Assembly had quickly reconvened in June 1781 in Staunton, Virginia across the Blue Ridge Mountains. They voted to reward Jouett with a pair of pistols and a sword, but considered an official inquiry into Jefferson's actions, as they believed he had failed his responsibilities as governor.

"The inquiry ultimately was dropped, yet Jefferson insisted on appearing before the lawmakers in December to respond to charges of mishandling his duties and abandoning leadership at a critical moment. He reported that he had believed it understood that he was leaving office and that he had discussed with other legislators the advantages of Gen. Thomas Nelson, a commander of the state militia, being appointed governor."[59]

(The legislature did appoint Nelson as governor in late June 1781.)

"Jefferson was a controversial figure at this time, heavily criticized for inaction and failure to adequately protect the state in the face of a British invasion. Even on balance, Jefferson had been a very poor state executive, and left his successor, Thomas Nelson, Jr., to pick up the pieces."[61]

He was not re-elected again to office in Virginia.[49]

Notes on the State of Virginia

In 1780 Jefferson as governor received numerous questions about Virginia, posed to him by François Barbé-Marbois, then Secretary of the French delegation in Philadelphia, the temporary capital of the united colonies, who intended to gather pertinent data on the American colonies. Jefferson's responses to Marbois' "Queries" would become known as Notes on the State of Virginia (1785). Scientifically trained, Jefferson was a member of the American Philosophical Society, which had been founded in Philadelphia in 1743. He had extensive knowledge of western lands from Virginia to Illinois. In a course of five years, Jefferson enthusiastically devoted his intellectual energy to the book; he included a discussion of contemporary scientific knowledge, and Virginia's history, politics, and ethnography. Jefferson was aided by Thomas Walker, George R. Clark, and U.S. geographer Thomas Hutchins. The book was first published in France in 1785 and in England in 1787.[62]

It has been ranked as the most important American book published before 1800. The book is Jefferson's vigorous and often eloquent argument about the nature of the good society, which he believed was incarnated by Virginia. In it he expressed his beliefs in the separation of church and state, constitutional government, checks and balances, and individual liberty. He also compiled extensive data about the state's natural resources and economy. He wrote extensively about the problems of slavery, miscegenation, and his belief that blacks and whites could not live together as free people in one society.

Member of Congress and Minister to France

Following its victory in the war and peace treaty with Great Britain, in 1783 the United States formed a Congress of the Confederation (informally called the Continental Congress), to which Jefferson was appointed as a Virginia delegate. As a member of the committee formed to set foreign exchange rates, he recommended that American currency should be based on the decimal system; his plan was adopted. Jefferson also recommended setting up the Committee of the States, to function as the executive arm of Congress. The plan was adopted but failed in practice.

Jefferson was "one of the first statesmen in any part of the world to advocate concrete measures for restricting and eradicating Negro slavery."[63] Jefferson wrote an ordinance banning slavery in all the nation's territories (not just the Northwest), but it failed by one vote. The subsequent Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery in the newly organized territory, but it did nothing to free slaves who were already held by settlers there; this required later actions. Jefferson was in France when the Northwest Ordinance was passed.[64]

He resigned from Congress when he was appointed as minister to France in May 1784.

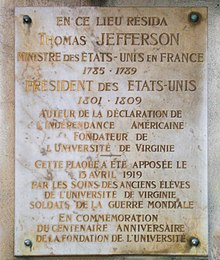

The widower Jefferson, still in his 40s, was minister to France from 1785 to 1789, the year the French Revolution started. When the French foreign minister, the Count de Vergennes, commented to Jefferson, "You replace Monsieur Franklin, I hear," Jefferson replied, "I succeed him. No man can replace him."[65]

Beginning in early September 1785, Jefferson collaborated with John Adams, US minister in London, to outline an anti-piracy treaty with Morocco. Their work culminated in a treaty that was ratified by Congress on July 18, 1787. Still in force today, it is the longest unbroken treaty relationship in U.S. history.[66] Busy in Paris, Jefferson did not return to the US for the 1787 Constitutional Convention.

He enjoyed the architecture, arts, and the salon culture of Paris. He often dined with many of the city's most prominent people, and stocked up on wines to take back to the US.[67] While in Paris, Jefferson corresponded with many people who had important roles in the imminent French Revolution. These included the Marquis de Lafayette, and the Comte de Mirabeau, a popular pamphleteer who repeated ideals that had been the basis for the American Revolution.[68] His observations of social tensions contributed to his anti-clericalism and strengthened his ideas about the separation of church and state.[citation needed]

Jefferson's eldest daughter Martha, known as Patsy, went with him to France in 1784. His two youngest daughters were in the care of friends in the United States.[57] To serve the household, Jefferson brought some of his slaves, including James Hemings, who trained as a French chef for his master's service.

Jefferson's youngest daughter Lucy died of whooping cough in 1785 in the United States, and he was bereft.[61] In 1786, Jefferson met and fell in love with Maria Cosway, an accomplished Italian-English artist and musician of 27. They saw each other frequently over a period of six weeks. A married woman, she returned to Great Britain, but they maintained a lifelong correspondence.[61]

In 1787, Jefferson sent for his youngest surviving child, Polly, then age nine. He requested that a slave accompany Polly on the trans-Atlantic voyage. By chance, Sally Hemings, a younger sister of James, was chosen; she lived in the Jefferson household in Paris for about two years. According to her son Madison Hemings, Sally and Jefferson began a sexual relationship in Paris and she became pregnant.[69] She agreed to return to the United States as his concubine after he promised to free her children when they came of age.[69]

Secretary of State

In September 1789 Jefferson returned to the US from France with his two daughters and slaves. Immediately upon his return, President Washington wrote to him asking him to accept a seat in his Cabinet as Secretary of State. Jefferson accepted the appointment.

As Washington's Secretary of State (1790–1793), Jefferson argued with Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury, about national fiscal policy,[70] especially the funding of the debts of the war. Jefferson later associated Hamilton and the Federalists with "Royalism," and said the "Hamiltonians were panting after ... crowns, coronets and mitres."[71] Due to their opposition to Hamilton, Jefferson and James Madison founded and led the Democratic-Republican Party. He worked with Madison and his campaign manager John J. Beckley to build a nationwide network of Republican allies. Jefferson's political actions and his attempt to undermine Hamilton nearly led Washington to dismiss Jefferson from his cabinet.[72] Although Jefferson left the cabinet voluntarily, Washington never forgave him for his actions, and never spoke to him again.[72]

The French minister said in 1793: "Senator Morris and Secretary of the Treasury Hamilton ... had the greatest influence over the President's mind, and that it was only with difficulty that he [Jefferson] counterbalanced their efforts."[73] Jefferson supported France against Britain when they fought in 1793.[74] Jefferson believed that political success at home depended on the success of the French army in Europe.[75] In 1793, the French minister Edmond-Charles Genêt caused a crisis when he tried to influence public opinion by appealing to the American people, something which Jefferson tried to stop.[75]

Jefferson tried to achieve three important goals during his discussions with George Hammond, British Minister to the U.S.: secure British admission of violating the Treaty of Paris (1783) ; vacate their posts in the Northwest (the territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River north of the Ohio); and compensate the United States to pay American slave owners for the slaves whom the British had freed and evacuated at the end of the war. Chester Miller notes that after failing to gain agreement on any of these, Jefferson resigned in December 1793.[76]

Election of 1796 and Vice Presidency

In late 1793, Jefferson retired to Monticello, from where he continued to oppose the policies of Hamilton and Washington. The Jay Treaty of 1794, led by Hamilton, brought peace and trade with Britain – while Madison, with strong support from Jefferson, wanted "to strangle the former mother country" without going to war.[77] "It became an article of faith among Republicans that 'commercial weapons' would suffice to bring Great Britain to any terms the United States chose to dictate."[77] Even during the violence of the Reign of Terror in France, Jefferson refused to disavow the revolution because "To back away from France would be to undermine the cause of republicanism in America."[78] As vice president, Jefferson conducted secret talks with the French, in which he advocated that the French government take a more aggressive position against the American government, which he thought was too close to the British.[79] He succeeded in getting the American ambassador expelled from France.

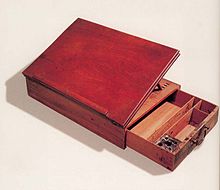

As the Democratic-Republican presidential candidate in 1796, Jefferson lost to John Adams, but had enough electoral votes to become Vice President (1797–1801). One of the chief duties of a Vice president is presiding over the Senate, and Jefferson was concerned about its lack of rules leaving decisions to the discretion of the presiding officer. Years before holding his first office, Jefferson had spent much time researching procedures and rules for governing bodies. As a student, he had transcribed notes on British parliamentary law into a manual which he would later call his Parliamentary Pocket Book. Jefferson had also served on the committee appointed to draw up the rules of order for the Continental Congress in 1776. As Vice President, he was ready to reform Senatorial procedures. Prompted by the immediate need, he wrote A Manual of Parliamentary Practice, a document which the House of Representatives follows to the present day.[80]

With the Quasi-War underway, the Federalists under John Adams started rebuilding the military, levied new taxes, and enacted the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson believed that these acts were intended to suppress Democratic-Republicans rather than dangerous enemy aliens, although the acts were allowed to expire. Jefferson and Madison rallied opposition support by anonymously writing the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which declared that the federal government had no right to exercise powers not specifically delegated to it by the states.[81] Though the resolutions followed the "interposition" approach of Madison, Jefferson advocated nullification. At one point he drafted a threat for Kentucky to secede.[Note 3] Jefferson's biographer Dumas Malone argued that had his actions become known at the time, Jefferson might have been impeached for treason.[79] In writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold," the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood."[79] The historian Ron Chernow says, "[H]e wasn't calling for peaceful protests or civil disobedience: he was calling for outright rebellion, if needed, against the federal government of which he was vice president."[82]

Chernow believes that Jefferson "thus set forth a radical doctrine of states' rights that effectively undermined the constitution."[82] He argues that neither Jefferson nor Madison sensed that they had sponsored measures as inimical as the Alien and Sedition Acts.[82] The historian Garry Wills argued, "Their nullification effort, if others had picked it up, would have been a greater threat to freedom than the misguided [alien and sedition] laws, which were soon rendered feckless by ridicule and electoral pressure."[83] The theoretical damage of the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions was "deep and lasting, and was a recipe for disunion".[82] George Washington was so appalled by them that he told Patrick Henry that if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", they would "dissolve the union or produce coercion."[82] The influence of Jefferson's doctrine of states' rights reverberated to the Civil War and beyond.[84]

According to Chernow, during the Quasi-War, Jefferson engaged in a "secret campaign to sabotage Adams in French eyes."[85] In the spring of 1797, he held four confidential talks with the French consul Joseph Letombe. In these private meetings, Jefferson attacked Adams, predicted that he would only serve one term, and encouraged France to invade England.[85] Jefferson advised Letombe to stall any American envoys sent to Paris by instructing them to "listen to them and then drag out the negotiations at length and mollify them by the urbanity of the proceedings." This toughened the tone that the French government adopted with the new Adams Administration.[85] Due to pressure against the Adams Administration from Jefferson and his supporters, Congress released the papers related to the XYZ Affair, which rallied a shift in popular opinion from Jefferson and the French government to supporting Adams.[85]

Presidency

Election of 1800 and first term

Working closely with Aaron Burr of New York, Jefferson rallied his party, attacking the new taxes especially, and ran for the Presidency in 1800. Before the passage of the Twelfth Amendment, a problem with the new union's electoral system arose.

Hamilton convinced his party that Jefferson would be a lesser political evil than Burr and that such scandal within the electoral process would undermine the new constitution. On February 17, 1801, after thirty-six ballots, the House elected Jefferson President and Burr Vice President.

Jefferson owed his election victory to the South's inflated number of Electors, which counted slaves under the three-fifths compromise.[86][87] After his election in 1800, some called him the "Negro President", with critics like the Mercury and New-England Palladium of Boston stating that Jefferson had the gall to celebrate his election as a victory for democracy when he won "the temple of Liberty on the shoulders of slaves."[87]

Thomas Jefferson took the oath of office on March 4, 1801, at a time when partisan strife between the Democratic-Republican and Federalist parties was growing to alarming proportions. Regarded by his supporters as the 'People's President' news of Jefferson's election was well received in many parts of the new country and was marked by celebrations throughout the Union. He was sworn in by Chief Justice John Marshall at the new Capitol in Washington DC. In contrast to the preceding president John Adams, Jefferson exhibited a dislike of formal etiquette. Unlike Washington, who arrived at his inauguration in a stagecoach drawn by six cream colored horses, Jefferson arrived alone on horseback without guard or escort. He was dressed plainly and after dismounting, retired his own horse himself.[88]

As a result of his two predecessors, as well as the state of events in Europe, Jefferson inherited the presidency with relatively few urgent problems. Though he and his supporters attempted to dismantle several of the accomplishments of his two predecessors, notably the national bank, military, and federal taxation system, they were only partially successful.[89]

Administration, Cabinet and Supreme Court appointments

|

States admitted to the Union:

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

First Barbary War

When Jefferson became president in 1801, the United States was at the time paying $80,000 to the Barbary states as a 'tribute' for protection against North African piracy. For decades, the pirates had been capturing American ships and crew members and demanding huge ransoms for their release. Before Independence, from 1775 until 1783, American merchant ships were protected from the Barbary pirates by the naval and diplomatic influence of Great Britain. When the American Revolution began, American ships were protected by the 1778 alliance with France, which required the French nation to protect "American vessels and effects against all violence, insults, attacks ...". On December 20, 1777, Morocco's Sultan Mohammed III declared that the American merchant ships would be under the protection of the sultanate and could thus enjoy safe passage into the Mediterranean and along the coast. The Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship stands as the U.S.'s oldest non-broken friendship treaty.[90][91] The one with Morocco has been the longest-lasting treaty with a foreign power.

After the United States gained independence, it had to protect its own merchant vessels. It also had to pay $80,000 as tribute to the Barbary states, as did Britain and France at this time. When Tripoli made new demands on the new President for a prompt payment of $225,000 and an annual payment of $25,000, Jefferson refused and decided it would be easier to fight the pirates than to continue to pay bribes. On May 10, 1801, the pasha of Tripoli declared war on the United States and the First Barbary War began. As secretary of state and vice president, Jefferson had opposed funds for a Navy to be used for anything more than a coastal defense, however the continued pirate attacks on American shipping interests in the Atlantic and Mediterranean and the systematic kidnapping of American crew members could no longer be ignored. President Jefferson ordered a fleet of naval vessels to various points in the Mediterranean. He forced Tunis and Algiers into breaking their alliance with Tripoli which ultimately forced it out of the fight. Jefferson also ordered five separate naval bombardments of Tripoli, which restored peace in the Mediterranean for a while.[92]

Louisiana Purchase

In 1803 in the midst of the Napoleonic wars between France and Britain, Thomas Jefferson authorized the Louisiana Purchase, a major land acquisition from France that doubled the size of the United States.

Most of France's wealth in the New World had come from its sugar plantations on Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe in the Caribbean, but production had fallen after a slave uprising. After sending more than 20,000 troops to try to regain the colony in 1802, France withdrew its 7,000 surviving troops in late 1803, shortly before Haiti declared independence.[93] Having lost the revenue potential of Haiti while escalating his wars against the rest of Europe, Napoleon gave up on an empire in North America and used the purchase money to help finance France's war campaign on its home front.[94][93]

Jefferson had sent James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston to Paris in 1802 to try to buy the city of New Orleans and adjacent coastal areas. At Jefferson's request, Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, a French nobleman who had close ties with both Jefferson and Napoleon, also helped negotiate the purchase with France. Napoleon offered to sell the entire Territory for a price of $15 million, which Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin financed easily. Seizing the opportunity Jefferson acted contrary to his usual requirement of explicit Constitutional authority, and the Federalists criticized him for acting without that authority, but most thought that this opportunity was exceptional and could not be missed.[95]

On December 20, 1803 the French flag was lowered in New Orleans and the U.S. flag raised, symbolizing the transfer of the Louisiana territory from France to the United States.[96] Jefferson's decision would prove to be the most consequential presidential decision in American history. [97] The territory was not finally secured until England and Mexico gave up their claims to northern and southern portions, respectively, during the presidency of James Polk. Without realizing it, at the time Jefferson had purchased one of the largest fertile tracts of land on the planet. As the purchase marked the end of French imperial ambitions in North America, the United States could develop a new national security strategy.

Historians differ in their assessments as to who was the principal player in the purchase; the Jefferson biographer Peterson notes a range of opinion among those who credit Napoleon, or others who credit Jefferson, his secretary of state James Madison, and his negotiator James Monroe. Peterson agrees with Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson's arch rival, in attributing it to "dumb luck".[98] Joseph Ellis, another biographer of Jefferson, believes the events encompassed a variety of elements.[99] The historian George Herring has said that while the purchase was somewhat the result of Jefferson and Madison's "shrewd and sometimes belligerent diplomacy", that it "is often and rightly regarded as a diplomatic windfall—the result of accident, luck, and the whim of Napoleon Bonaparte."[100]

With France removed as a threat, Jefferson followed the southern-dominated Congress, which feared a slave revolt at home due to the rise of Haiti. The United States refused to recognized the new republic, the second in the Western Hemisphere, and imposed an arms and trade embargo against it. This made it difficult for the country to recover after the wars.[101]

Lewis and Clark Expedition

Jefferson had an avid interest in the sciences and had long entertained ideas of exploring the American frontier before Louisiana was purchased from France. As such Jefferson was a member of the American Philosophical Society, founded in Philadelphia in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin, and served as its President from 1797 to 1815. By the turn of the 19th century, the society was well established and staffed, and equipped for research. Jefferson made use of its resources by sending Meriwether Lewis to Philadelphia in 1803 for instruction at the Society in botany, mathematics, surveying, astronomy, chemistry and map making, among other subjects.[102] On January 18, 1803, Jefferson sent a confidential letter to Congress asking for $2,500 to fund an expedition through the West; on February 28, 1803, Congress appropriated the necessary funds.[103]

In 1804 Jefferson appointed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark as leaders of the expedition (1804–1806), which explored the Louisiana Territory and beyond, producing a wealth of scientific and geographical knowledge, and ultimately contributing to the European-American settlement of the West.[104] Knowledge of the western part of the continent had been scant and incomplete, limited to what had been learned from trappers, traders, and explorers. This was the first official American military expedition to the Pacific Coast. Lewis and Clark, for whom the expedition became known, recruited the 45 men to accompany them, and spent a winter training them near St. Louis for the effort.[105]

The expedition had several goals identified by Jefferson, including finding a "direct & practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce" (the long-sought Northwest Passage).[105] They were to follow and map the rivers, and collect scientific data. He was deeply interested in opportunities for the lucrative fur trade. Jefferson wanted to establish a US claim of "discovery" of the Pacific Northwest by mapping and documenting a United States presence there before Europeans could claim the land. The expedition reached the Pacific Ocean by November 1805. With its return in 1806, it had fulfilled Jefferson's hopes by amassing much new data about the topographical features of the country and its natural resources, with details on the flora and fauna, as well as the many Indian tribes of the West with which he hoped to increase trading.[106]

Jefferson also commissioned the Pike expedition to explore the central region of the Louisiana Purchase, and the Red River Expedition, which was less successful.[107][108]

West Point

Ideas for a national institution for military education were circulated during the American Revolution. In May 1801 the Secretary of War Henry Dearborn announced that the president had appointed Major Jonathan Williams, grandnephew of Benjamin Franklin, to direct organizing to establish such a school.[109] Following the advice of George Washington, John Adams and others,[110] in 1802 Jefferson convinced Congress to authorize the funding and construction of the United States Military Academy at West Point on the Hudson River in New York. On March 16, 1802, Jefferson signed the Military Peace Establishment Act, directing that a corps of engineers be established and "constitute a Military Academy."[111] The Act would provide well-trained officers for a professional army. The officers would be reliable republicans rather than a closed elite as in Europe, for the cadets were to be appointed by Congressmen to reflect the nation's politics. On July 4, 1802, the US Military Academy at West Point formally started as an institution for scientific and military learning.[111]

Native American policy

As governor of Virginia (1780-1781) during the Revolutionary War, Jefferson recommended forcibly moving Cherokee and Shawnee tribes that fought on the British side to lands west of the Mississippi River. Later, as president, Jefferson proposed in private letters beginning in 1803 a policy that under Andrew Jackson would be called Indian removal, under an act passed in 1830.[112][113] As president, he made a deal with elected officials of the state of Georgia: if Georgia would release its legal claims to "discovery" in lands to its west, the U.S. military would help expel the Cherokee people from Georgia. His deal violated an existing treaty between the United States government and the Cherokee Nation, which guaranteed its people the right to their historic lands.[112]

Jefferson believed that Natives should give up their own cultures, religions, and lifestyles to assimilate to western European culture, Christian religion, and a European-style agriculture, which he believed to be superior.[112][113] He believed that assimilation of Native Americans into the European-American economy would make them more dependent on trade, and that they would eventually be willing to give up land that they would otherwise not part with, in exchange for trade goods or to resolve unpaid debts.[114] In keeping with his trade and acculturation policy, Jefferson kept Benjamin Hawkins as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Southeastern peoples, who became known as the Five Civilized Tribes for their adoption of European-American ways.

Jefferson believed assimilation was best for Native Americans; second best was removal to the west. He felt the worst outcome of the cultural and resources conflict between European Americans and Native Americans would be their attacking the whites.[115] He told his Secretary of War, General Henry Dearborn (Indian affairs were then under the War Department): "if we are constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe, we will never lay it down until that tribe is exterminated, or driven beyond the Mississippi."[116] With the colonial and native civilizations in collision, compounded by British incitement of Indian tribes and mounting hostilities between the two peoples, Jefferson's administration took quick measures to avert another major conflict. His deal with Georgia was related to later measures to relocate the various Indian tribes to points further west.[112]

1804 election and second term

In his second term, Jefferson's popularity suffered because the problems he faced, most notably those caused by the wars in Europe, became more difficult to solve. During Jefferson's first term, Napoleon's position was relatively weak and as such negotiations were possible. After Napoleon's decisive victory at the Battle of Austerlitz in 1805, however, Napoleon became much more aggressive, and most United States attempts to negotiate with him were unsuccessful. Jefferson responded with the Embargo Act of 1807, directed also at Great Britain. This triggered economic chaos in the US and was strongly criticized at the time, as it continues to be.[117] Due to political attacks against Jefferson, in particular those by Alexander Hamilton and his supporters, he used the Alien and Sedition Acts to counter some of these political adversaries.[118] In 1807, Jefferson ordered his former vice president Aaron Burr tried for treason. Burr was charged with conspiring to levy war against the United States in an attempt to establish a separate confederacy composed of the Western states and territories, but he was acquitted.[119][120]

The US Constitution of 1787 provided for protection of the international slave trade for two decades, during which planters of the Lower South imported tens of thousands of slaves, more than during any other 20-year period.[121] In December 1806 Jefferson called on Congress to take action and in 1807, it passed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves. This was the earliest that the trade could be regulated; Jefferson signed and the law went into effect January 1, 1808.[122] While the act established severe punishment against the international trade, it did not regulate the domestic slave trade.

Embargo

Jefferson encouraged passage of the Embargo Act in 1807 to maintain American neutrality in the Napoleonic Wars. Jefferson hoped to avoid national humiliation on the one hand, and war on the other. In the event, he got both war and national humiliation; the economy of the entire Northeast suffered severely, Jefferson was vehemently denounced, and his party lost support. Instead of retreating, Jefferson sent federal agents to secretly track down smugglers and violators.[123][124]

The embargo was a financial disaster because the Americans could not export, while widespread disregard of the law meant enforcement was difficult. For the most part, it effectively throttled American overseas trade. All areas of the United States suffered. In commercial New England and the Middle Atlantic states, ships rotted at the wharves, and in the agricultural areas, particularly in the South, farmers and planters could not export their crops. Jefferson's Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin was against the embargo, foreseeing correctly the impossibility of enforcing the policy and the negative public reaction. "As to the hope that it may...induce England to treat us better," wrote Gallatin to Jefferson shortly after the bill had become law, "I think is entirely groundless...government prohibitions do always more mischief than had been calculated; and it is not without much hesitation that a statesman should hazard to regulate the concerns of individuals as if he could do it better than themselves."[125]

Though he had so frequently argued for as small a federal government as possible, Jefferson required the national government to assume extraordinary police powers in an attempt to enforce his policy. The presidential election of 1808, which James Madison won, showed that the Federalists were regaining strength, and helped to convince Congress that the Embargo would have to be repealed. Shortly before leaving office, in March 1809, Jefferson signed the repeal of the disastrous Embargo. In its place the Nonintercourse Act was enacted, which proved no more effective than the Embargo. The government found it was impossible to prevent American vessels from trading with the European belligerents once they had left American ports. Jefferson increasingly believed the problem was the greedy traders and merchants who showed their lack of "republican virtue" by not complying.[126]

Historians have generally criticized Jefferson for his embargo policy. Cogliano notes that the failure of the Embargo "reinforced the view that Jefferson had been lucky rather than adroit during the earlier negotiations."[127] Doron Ben Atar argued that Jefferson's commercial and foreign policies were misguided, ineffective and harmful to American interests.[128] Kaplan argued that the War of 1812 was the logical extension of his embargo and that, by entering the Napoleonic Wars on anti-British side, the United States gave up the advantages of neutrality.[129] Kaplan adds, "The results were a personal disaster for Jefferson and general malaise and confusion for the nation."[130] Bradford Perkins concluded that on this issue, Jefferson was "a wavering, miscalculating, and self-deluding man."[131]

Other involvements

He obtained the repeal of some federal taxes in his bid to rely more on customs revenue, and dismantled much of the army and navy that he had inherited from Washington and Adams. He pardoned several people imprisoned under the Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in John Adams' term. He repealed the Judiciary Act of 1801, which removed nearly all of Adams' "midnight judges" from office. This quickly led to the Supreme Court deciding the important case of Marbury v. Madison. This also repealed a provision in the act that freed supreme court justices from having to constantly travel the country to serve as circuit court judges. This provision wasn't reinstated for another century, and its repeal under Jefferson ensured that justices would continue to bear heavy travel burdens throughout the nineteenth century. Jefferson also signed into law a bill that officially segregated the US postal system by not allowing blacks to carry mail.[132]

Later years

By 1815, Jefferson's library included 6,487 books, which he sold to the Library of Congress for $23,950 to replace the smaller collection destroyed in the War of 1812. He intended to pay off some of his large debt, but immediately started buying more books.[57] In honor of Jefferson's contribution, the library's website for federal legislative information was named THOMAS.[133][134] In 2007, Jefferson's two-volume 1764 edition of the Quran was used by Rep. Keith Ellison for his swearing in to the House of Representatives.[135] In February 2011 the New York Times reported that a part of Jefferson's retirement library, containing 74 volumes with 28 book titles, was discovered at Washington University in St. Louis.[134]

University of Virginia

After leaving the Presidency, Jefferson continued to be active in public affairs. He wanted to found a new institution of higher learning, specifically one free of church influences, where students could specialize in many new areas not offered at other universities. Jefferson believed educating people was a good way to establish an organized society. He believed such schools should be paid for by the general public, so less wealthy people could be educated as students.[136] A letter to Joseph Priestley, in January 1800, indicated that he had been planning the University for decades before its founding.

In 1819 he founded the University of Virginia. Upon its opening in 1825, it was the first university to offer a full slate of elective courses to its students. One of the largest construction projects to that time in North America, the university was notable for being centered about a library rather than a church. No campus chapel was included in Jefferson's original plans. Until his death, Jefferson invited students and faculty of the college to his home.

Jefferson is widely recognized[by whom?] for his planning of the University grounds. Its innovative design was an expression of his aspirations for both state-sponsored education and an agrarian democracy in the new Republic. His educational idea of creating specialized units of learning is expressed in the configuration of his campus plan, which he called the "Academical Village". Individual academic units were defined as distinct structures, represented by Pavilions, facing a grassy quadrangle. Each Pavilion housed classroom, faculty office, and residences. Though distinctive, each is visually equal in importance, and they are linked with a series of open-air arcades that are the front facades of student accommodations. Gardens and vegetable plots are placed behind and surrounded by serpentine walls, affirming the importance of the agrarian lifestyle.

His highly ordered site plan establishes an ensemble of buildings surrounding a central rectangular quadrangle, named The Lawn, which is lined on either side with the academic teaching units and their linking arcades. The quad is enclosed at one end with the library, the repository of knowledge, at the head of the table. The remaining side opposite the library remained open-ended for future growth. The lawn rises gradually as a series of stepped terraces, each a few feet higher than the last, rising up to the library set in the most prominent position at the top, while also suggesting that the Academical Village facilitates easier movement to the future.

Stylistically, Jefferson was a proponent of the Greek and Roman styles, which he believed to be most representative of American democracy by historical association. Each academic unit is designed with a two story temple front facing the quadrangle, while the library is modeled on the Roman Pantheon. The ensemble of buildings surrounding the quad is an unmistakable architectural statement of the importance of secular public education, while the exclusion of religious structures reinforces the principle of separation of church and state. The campus planning and architectural treatment remains today as a paradigm of building of structures to express intellectual ideas and aspirations. A survey of members of the American Institute of Architects identified Jefferson's campus as the most significant work of architecture in America.

The University was designed as the capstone of the educational system of Virginia. In his vision, any citizen of the state could attend school with the sole criterion being ability.[137][138]

Death

Jefferson' health began to deteriorate by July 1825, and by June 1826 he was confined to bed. His death was from a combination of illnesses and conditions including uremia, severe diarrhea, and pneumonia.[139] Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and a few hours before John Adams.

Though born into a wealthy slave-owning family, Jefferson had many financial problems, and died deeply in debt.[140] He gave instructions for disposal of his assets in his Will[141] and after his death, his possessions (including 130 persons he held as slaves) were sold off in public auctions starting in 1827.[140] Monticello was sold in 1831.

Thomas Jefferson is buried in the family cemetery at Monticello. The cemetery is separately owned and operated by the Monticello Association, a lineage society that is not affiliated with the Thomas Jefferson Foundation that runs the estate as a public history site.

Jefferson wrote his own epitaph, which reads:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON

AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM

AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA.

Political philosophy and views

Jefferson idealized the independent yeoman as the best exemplar of republican virtues, distrusted cities and financiers, and favored states' rights and a strictly limited federal government. He suspended his qualms about exercising powers of federal government to buy Louisiana. Jefferson detested the European system of established churches and called for a wall of separation between church and state at the federal level. He helped disestablish the Church of England, called the Anglican Church in Virginia after the Revolution, [142] and wrote the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (also known as 'The Act for Establishing Religious Freedom') (1779, 1786). [143]

His Jeffersonian democracy and Democratic-Republican Party became dominant in American politics. Jefferson's republican political principles were strongly influenced by the 18th-century British opposition writers of the Country Party. He had high regard for John Locke, Francis Bacon, and Isaac Newton.[144]

Society and government

Jefferson believed that each man has "certain inalienable rights". He defines the right of "liberty" by saying, "Rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others..."[145] A proper government, for Jefferson, is one that not only prohibits individuals in society from infringing on the liberty of other individuals, but also restrains itself from diminishing individual liberty. Jefferson and contemporaries like James Madison were well aware of the possibility of tyranny from the majority and held this perspective in their implication of individual rights. [146] The historian Gordon S. Wood argues that Jefferson's political philosophy was a product of his time and his scientific interests. Influenced by Isaac Newton, he considered social systems as analogous to physical systems.[147] In the social world, Jefferson likens love as a force similar to gravity in the physical world. People are naturally attracted to each other through love, but dependence corrupts this attraction and results in political problems.[147] Wood argues that, though the phrase "all men are created equal" was a cliché in the late 18th century,[147] Jefferson took it further than most. Jefferson held that not only are all men created equal, but they remain equal throughout their lives, equally capable of love as an attractive force. Their level of dependence makes them unequal in practice. Removing or preventing corrupting dependence would enable men to be equal in practice.[147] Jefferson idealized a future in which men would be free of dependencies, particularly those caused by banking or royal influences.[147]

In political terms, Americans thought that virtue was the "glue" that held together a republic, whereas patronage, dependency and coercion held together a monarchy. "Virtue" in this sense was public virtue, in particular self-sacrifice. People commonly thought that any dependence would corrupt this impulse, by making people more subservient to their patrons than to society at large. This derived from the British conception of the nobility, whose economic independence allowed them to work and make personal sacrifices on behalf of the society at large. Americans reasoned that liberty and republicanism required a virtuous society, and the society had to be free of dependence and extensive patronage networks.[147] Jefferson's ideal of the yeoman farmer (or a slave-owning planter) personified his ideal of independence. While Jefferson believed most persons could not escape corrupting dependence, the franchise should be extended only to those who could. His fear of dependence and patronage made Jefferson dislike established institutions, such as banking, government, or military. He disliked inter-generational dependence, as well as its manifestations, such as national debt and unalterable governments. For these reasons, he opposed Hamilton's consolidated banking and military plans.[147] Jefferson and Hamilton were diametrically opposed on the issue of individual liberties. While Jefferson believed individual liberty was the fruit of equality and believed government to be the only danger, Hamilton felt that individual liberty must be organized by a central government to assure social, economic and intellectual equality. [148] Wood argues that Hamilton favored his plans for the very reason that Jefferson feared them, because he believed that they would provide for future American greatness. Jefferson feared a loss of individual liberty for propertied individuals and did not desire imperial stature for the nation.[147]

During the late 1780s, James Madison grew to believe that self-interested dependence could be filtered from a government. Jefferson, however, continued to idealize the yeoman farmer as the base for republican government.[147] Whereas Madison became disillusioned with what he saw as excessive democracy in the states, Jefferson believed such excesses were caused by institutional corruptions rather than human nature. He remained less suspicious of working democracy than many of his contemporaries.[147]

Wood argues that as president, Jefferson tried to re-create the balance between the states and federal government as it existed under the Articles of Confederation. He tried to shift the balance of power back to the states. Wood argues that Jefferson took this action from his classical republican conception that liberty could only be retained in small, homogeneous societies. He believed that the Federalist system enacted by Washington and Adams had encouraged corrupting patronage and dependence.[147] According to Wood, many of Jefferson's apparent contradictions can be understood within this philosophical framework. For example, his intent to deny women the franchise was rooted in his belief that a government must be controlled by the independent. In the 18th century, men believed that women were dependent by their nature. In common with most political thinkers of his day, Jefferson did not support gender equality. He opposed women's participation in politics, saying that "our good ladies ... are contented to soothe and calm the minds of their husbands returning ruffled from political debate."[149]

Democracy

Jefferson is a major iconic figure in the emergence of democracy—he was the "agrarian democrat" who shaped the thinking of his nation and the world.[150][151] The historian Vernon Louis Parrington concluded in 1927:

- "Far more completely than any other American of his generation he embodied the idealisms of the great revolution – its faith in human nature, its economic individualism, its conviction that here in America, through the instrumentality of political democracy, the lot of the common man should somehow be made better."[152]

Jefferson's concepts of democracy were rooted in The Enlightenment, as Peter Onuf has stressed. He envisioned democracy as an expression of society as a whole, and he called for national self-determination, cultural uniformity, and education of all the people (or all the males, as he believed at the time). His emphasis on uniformity did not envision a multiracial republic in which some groups were not fully assimilated into the identical republican values. Onuf argues that Jefferson was unable and unwilling to abolish slavery until such a demand could issue naturally from the sensibilities of the entire people.[153] Gordon Wood argues that Jefferson's philosophy of liberty personified American ideals.[154] Jefferson believed that public education and a free press were essential to a democratic nation: "If a nation expects to be ignorant and free it expects what never was and never will be....The people cannot be safe without information. Where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe".[155]

Banks

Jefferson expressed a dislike and distrust for banks and bankers; he opposed borrowing from banks because he believed it created long-term debt as well as monopolies, and inclined the people to dangerous speculation, as opposed to productive labor on the farm.[156] He felt that each generation should pay back its debt within 19 years, and not impose a long-term debt on subsequent generations. Jefferson fought against Hamilton's proposed Bank of the United States in 1790, but lost. Jefferson also opposed the bank loans that financed the War of 1812 fearing it would compromise the war effort and plunge the nation into serious long term debt. [157]

He was indifferent with many of his fellow tobacco planters however, as they felt that banks were needed to finance the purchase of new land and new slaves, and support commerce.[158] Jefferson often attacked banks, paper money and borrowing as inimical to Republicanism;[159] in retirement in 1816, he wrote John Taylor:

- The system of banking we have both equally and ever reprobated. I contemplate it as a blot left in all our constitutions, which, if not covered, will end in their destruction, which is already hit by the gamblers in corruption, and is sweeping away in its progress the fortunes and morals of our citizens.[160]

Foreign policy

Tucker and Hendrickson say that Jefferson believed America "was the bearer of a new diplomacy, founded on the confidence of a free and virtuous people, that would secure ends based on the natural and universal rights of man, by means that escaped war and its corruptions."[161] Jefferson sought a radical break from the traditional European emphasis on "reason of state" (which could justify any action) and the traditional priority of foreign policy and the needs of the ruling family over the needs of the people.

Jefferson envisaged America becoming the world's great "empire of liberty"--that is, the model for democracy and republicanism. On departing the presidency in 1809, he described America as:

- "Trusted with the destinies of this solitary republic of the world, the only monument of human rights, and the sole depository of the sacred fire of freedom and self-government, from hence it is to be lighted up in other regions of the earth, if other regions of the earth shall ever become susceptible of its benign influence."[162]

This statement expresses Jefferson's refusal as president to diplomatically recognize Haiti, founded in 1804 as the second republic in the world, after its successful slave revolution in the French colony of Saint-Domingue. Fearing the success of the "slave republic" would rouse the American South's slaves to rebellion, Jefferson supported an arms and trade embargo against Haiti.[163] But, during the revolution, when Jefferson had wanted to discourage French efforts in 1802-1803 at regaining control (and rebuilding their empire in North America), he had allowed arms and contraband goods to reach Saint-Domingue.[164]

In the decades after the Revolutionary War, Jefferson considered Britain as an enemy to the United States because it was the base for a successful aristocracy and antipathy to democracy, while France, at least in the early stages of the French Revolution, appeared to be developing a solution to Europe's malaise. He said, "The liberty of the whole world was depending on the issue of the contest."[165] He never wanted war. The paradox was that as Britain was much more powerful and was the leading trading partner of the U.S., Jefferson's economic warfare against the kingdom resulted in hurting the American economy.[166]

Rebellion and individual rights

After the Revolutionary War, Jefferson advocated restraining government via rebellion and violence when necessary, in order to protect individual freedoms. In a letter to James Madison on January 30, 1787, Jefferson wrote, "A little rebellion, now and then, is a good thing, and as necessary in the political world as storms in the physical...It is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government."[167] Similarly, in a letter to Abigail Adams on February 22, 1787 he wrote, "The spirit of resistance to government is so valuable on certain occasions that I wish it to be always kept alive. It will often be exercised when wrong, but better so than not to be exercised at all."[167] Concerning Shays' Rebellion after he had heard of the bloodshed, on November 13, 1787 Jefferson wrote to William S. Smith, John Adams' son-in-law, "What signify a few lives lost in a century or two? The tree of liberty must from time to time be refreshed with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure."[168] In another letter to Smith during 1787, Jefferson wrote: "And what country can preserve its liberties, if the rulers are not warned from time to time, that this people preserve the spirit of resistance? Let them take arms."[167]

Slavery

Jefferson lived in the "slave society" of Virginia and the South, where slavery was at "the center of economic production" and slaveholders comprised the ruling class.[169][170] As an elite, slaveholders were limited in number and controlled the political power. Jefferson owned hundreds of slaves to work plantations totaling more than ten thousand acres[171] and relied on slavery to support his family's way of life. Notable for his idealistic words on the rights of man in the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson shared contemporary racial views that Africans were inferior to whites and needed supervision. This became his rationale for justifying slavery, although he had condemned the institution under his Enlightenment ideals.

Jefferson opposed the international slave trade. In the Virginia Assembly, in the 1780s Jefferson gained passage of a bill to prohibit the state from importing slaves. The scholar Paul Finkleman suggests that Virginia planters passed the bill to raise the economic value of domestic slaves, rather than from an interest in abolishing slavery.[172] As president, on March 2, 1807 Jefferson signed the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves, which outlawed the international slave trade in U.S. and took effect January 1, 1808; it had been protected for 20 years under compromises in the United States Constitution to satisfy southern slaveholders.[173]