DuPont (1802–2017)

| |

| Company type | Public company |

|---|---|

| NYSE: DD Dow Jones Industrial Average Component S&P 500 Component | |

| Industry | Chemicals |

| Founded | 1802 |

| Founder | Eleuthère Irénée du Pont |

| Headquarters | Wilmington, Delaware, U.S. |

Key people | Ellen Kullman (Chair of the Board & CEO) |

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 70,000 (2012)[2] |

| Website | DuPont.com |

E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, commonly referred to as DuPont, is an American chemical company that was founded in July 1802 as a gunpowder mill by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont. DuPont was the world's third largest chemical company based on market capitalization and ninth based on revenue in 2009. Its stock price is a component of the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

In the 20th century, DuPont developed many polymers such as Vespel, neoprene, nylon, Corian, Teflon, Mylar, Kevlar, Zemdrain, M5 fiber, Nomex, Tyvek, Sorona and Lycra. DuPont developed Freon (chlorofluorocarbons) for the refrigerant industry, and later more environmentally friendly refrigerants. It developed synthetic pigments and paints including ChromaFlair.

The company has been involved in several controversies, and has been accused of adding to air and water pollution.

History

Establishment: 1802

DuPont was founded in 1802 by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, using capital raised in France and gunpowder machinery imported from France. The company was started at the Eleutherian Mills, on the Brandywine Creek, near Wilmington, Delaware two years after his family and he left France to escape the French Revolution. It began as a manufacturer of gunpowder, as du Pont noticed that the industry in North America was lagging behind Europe. The company grew quickly, and by the mid 19th century had become the largest supplier of gunpowder to the United States military, supplying half the powder used by the Union Army during the American Civil War. The Eleutherian Mills site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1966 and is now a museum.

Expansion: 1902 to 1912

DuPont continued to expand, moving into the production of dynamite and smokeless powder. In 1902, DuPont's president, Eugene du Pont, died, and the surviving partners sold the company to three great-grandsons of the original founder. The company subsequently purchased several smaller chemical companies, and in 1912 these actions gave rise to government scrutiny under the Sherman Antitrust Act. The courts declared that the company's dominance of the explosives business constituted a monopoly and ordered divestment. The court ruling resulted in the creation of the Hercules Powder Company (now Hercules Inc.) and the Atlas Powder Company (purchased by Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and now part of AkzoNobel).[3] At the time of divestment, DuPont retained the single base nitrocellulose powders, while Hercules held the double base powders combining nitrocellulose and nitroglycerine. DuPont subsequently developed the Improved Military Rifle (IMR) line of smokeless powders.[4]

In 1910, DuPont published a brochure entitled "Farming with Dynamite". The pamphlet was instructional, outlining the benefits to using their dynamite products on stumps and various other obstacles that would be easier to detonate with dynamite as opposed to other more conventional, inefficient means.[5]

DuPont also established two of the first industrial laboratories in the United States, where they began the work on cellulose chemistry, lacquers and other non-explosive products. DuPont Central Research was established at the DuPont Experimental Station, across the Brandywine Creek from the original powder mills.

Automotive investments: 1914

In 1914, Pierre S. du Pont invested in the fledgling automobile industry, buying stock of General Motors (GM). The following year he was invited to sit on GM's board of directors and would eventually be appointed the company's chairman. The DuPont company would assist the struggling automobile company further with a $25 million purchase of GM stock. In 1920, Pierre S. du Pont was elected president of General Motors. Under du Pont's guidance, GM became the number one automobile company in the world. However, in 1957, because of DuPont's influence within GM, further action under the Clayton Antitrust Act forced DuPont to divest itself of its shares of General Motors.

Major breakthroughs: 1920s-1930s

In the 1920s DuPont continued its emphasis on materials science, hiring Wallace Carothers to work on polymers in 1928. Carothers discovered neoprene, the first synthetic rubber; the first polyester superpolymer; and, in 1935, nylon. The discovery of Teflon followed a few years later. DuPont introduced phenothiazine as an insecticide in 1935.

Second World War: 1941 to 1945

DuPont ranked 15th among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.[6] As the inventor and manufacturer of nylon, DuPont helped produce the raw materials for parachutes, powder bags,[7] and tires.[8]

DuPont also played a major role in the Manhattan Project in 1943, designing, building and operating the Hanford plutonium producing plant in Hanford, Washington. In 1950 DuPont also agreed to build the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina as part of the effort to create a hydrogen bomb.

Space Age developments: 1950 to 1970

After the war, DuPont continued its emphasis on new materials, developing Mylar, Dacron, Orlon, and Lycra in the 1950s, and Tyvek, Nomex, Qiana, Corfam, and Corian in the 1960s. DuPont materials were critical to the success of the Apollo Project of the United States space program.

DuPont has been the key company behind the development of modern body armor. In the Second World War DuPont's ballistic nylon was used by Britain's Royal Air Force to make flak jackets. With the development of Kevlar in the 1960s, DuPont began tests to see if it could resist a lead bullet. This research would ultimately lead to the bullet resistant vests that are the mainstay of police and military units in the industrialized world.

Conoco holdings: 1981 to 1995

In 1981, DuPont acquired Conoco Inc., a major American oil and gas producing company that gave it a secure source of petroleum feedstocks needed for the manufacturing of many of its fiber and plastics products. The acquisition, which made DuPont one of the top ten U.S.-based petroleum and natural gas producers and refiners, came about after a bidding war with the giant distillery Seagram Company Ltd., which would become DuPont's largest single shareholder with four seats on the board of directors. On April 6, 1995, after being approached by Seagram Chief Executive Officer Edgar Bronfman, Jr., DuPont announced a deal whereby the company would buy back all the shares owned by Seagram.

Divestiture: 1999

In 1999, DuPont sold all of its shares of Conoco, which merged with Phillips Petroleum Company.

Current activities

| 2010 | 949 |

| 2009 | 171 |

| 2008 | 992 |

| 2007 | 1,652 |

| 2006 | 1,947 |

| 2005 | 2,795 |

| 2004 | −714 |

| 2003 | −428 |

| 2002 | 1,227 |

| 2001 | 6,131 |

DuPont describes itself as a global science company that employs more than 60,000 people worldwide and has a diverse array of product offerings.[10] In 2005, the Company ranked 66th in the Fortune 500 on the strength of nearly $28 billion in revenues and $1.8 billion in profits.[11]

DuPont businesses are organized into the following five categories, known as marketing "platforms": Electronic and Communication Technologies, Performance Materials, Coatings and Color Technologies, Safety and Protection, and Agriculture and Nutrition.

The agriculture division, Dupont Pioneer makes and sells hybrid seed and genetically modified seed, some of which goes on to become genetically modified food. Genes engineered into their products include the LibertyLink gene, which provides resistance to Bayer's Ignite/Liberty herbicides; the Herculex I Insect Protection gene which provides protection against various insects; the Herculex RW insect protection trait which provides protection against other insects; the YieldGard Corn Borer gene, which provides resistance to another set of insects; and the Roundup Ready Corn 2 trait that provides crop resistance against glyphosate herbicides.[12] In 2010 Dupont Pioneer received approval to start marketing Plenish soybeans, which contains "the highest oleic acid content of any commercial soybean product, at more than 75%. Plenish provides a product with no trans fat, 20% less saturated fat than regular soybean oil, and more stabile oil with greater flexibility in food and industrial applications."[13] Plenish is genetically engineered to "block the formation of enzymes that continue the cascade downstream from oleic acid (that produces saturated fats), resulting in an accumulation of the desirable monounsaturated acid."[14]

Safety has always been a key focus to the company. “The Goal is Zero” - zero injuries or incidents - thus, became one of the most important core values of the company. The company pays close attention to every incident no matter it is small or big. Also, DuPont has the tradition of having safety meetings and reports every week. Some of the key messages of "The Goal is Zero" is:

- There is no silver bullet, no single answer, to improving process safety.

- The goal has to be ZERO process-related injuries and incidents. The question is, not IF, but HOW, this goal can be achieved, just as it is for personal safety.

- PSM is a business issue, not only a manufacturing issue, requiring the contributions of a broad cross section of the organization to ensure success.

- Businesses therefore need to establish a sustainable continuous improvement process toward achieving the goal of zero PSM injuries and incidents that is embedded in business planning.

In 2004 the company sold its textiles business, which included some of its best-known brands such as Lycra (Spandex), Dacron polyester, Orlon acrylic, Antron nylon and Thermolite, to Koch Industries. DuPont also manufactures Surlyn, which is used for the covers of golf balls, and, more recently, the body panels of the Club Car Precedent golf cart.

As of 2011, DuPont is the largest producer of titanium dioxide in the world, primarily provided as a white pigment used in the paper industry.[16]

DuPont was listed No. 4 on the Mother Jones Top 20 polluters of 2010; dumping over 5,000,000 pounds of toxic chemicals into New Jersey/Delaware waterways.[17]

DuPont has its R&D facilities located in China, Japan, Taiwan, India, Germany, and Switzerland with an average investment of $1.3 billion annually in a diverse range of technologies for many markets including agriculture, genetic traits, biofuels, automotive, construction, electronics, chemicals, and industrial materials. DuPont employs more than 5,000 scientists and engineers around the world.[18]

On January 9, 2011, DuPont announced that it had reached a definitive agreement to buy Danish company Danisco for US$6.3 billion.[19] On May 16, 2011, DuPont announced that its tender offer for Danisco had been successful and that it would proceed to redeem the remaining shares and delist the company.[20] In February 2013, DuPont Performance Coatings was sold to the Carlyle Group and rebranded as Axalta Coating Systems.[21]

Locations

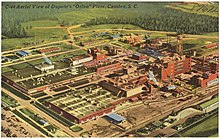

The company’s corporate headquarters are located in Wilmington, Delaware. The company’s manufacturing, processing, marketing, and research and development facilities, as well as regional purchasing offices and distribution centers are located throughout the world.[22] Major manufacturing sites include the Spruance plant near Richmond, Virginia (currently the company's largest plant), the Mobile Manufacturing Center (MMC) in Axis, Alabama, the Bayport plant near Houston, Texas, the Mechelen site in Belgium, and the Changshu site in China.[23] Other locations include the Yerkes Plant on the Niagara River at Tonawanda, New York, the Sabine River Works Plant in Orange, Texas, and the Parlin Site in Sayreville, New Jersey. The facilities in Vadodara, Gujarat, Hyderabad, and Andhra Pradesh in India constitute the Du Pont Services Center and Du Pont Knowledge Center.

Corporate governance

Current board of directors

- Ellen J. Kullman – President, Chair and CEO

- Lamberto Andreotti

- Richard H. Brown

- Robert A. Brown

- Bertrand P. Collomb

- Curtis J. Crawford

- Alexander M. Cutler

- There du Pont

- Marillyn Hewson

- Lois D. Juliber

- Lee M. Thomas[24]

The board of directors elected Ellen J. Kullman president and a director of the company with effect from October 1, 2008, Chief Executive Officer with effect from January 1, 2009,[25] and Chairman effective December 31, 2009.[26][27]

Environmental record

In 2005, BusinessWeek magazine, in conjunction with the Climate Group, ranked DuPont as the best-practice leader in cutting their carbon gas emissions.[28][29] They pointed out that DuPont reduced its greenhouse gas emissions by more than 65% from the 1990 levels while using 7% less energy and producing 30% more product. May 24, 2007 marked the opening of the 2.1 million USD DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor Reserve, a wildlife observatory and interpretive center on the Delaware Bay near Milford, Delaware. DuPont contributed both financial and technological support to create the center, as part of its "Clear into the Future" initiative to enhance the beauty and integrity of the Delaware Estuary. The facility will be state-owned and operated by the Delaware Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control (DNREC).[30][31] DuPont is a founding member of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development with DuPont CEO (at the time) Chad Holliday being Chairman of the WBCSD from 2000 to 2001. However, in 2010, researchers at the Political Economy Research Institute of the University of Massachusetts Amherst ranked DuPont as the fourth largest corporate source of air pollution in the United States.[32]

Genetically modified foods

A lawsuit filed against Pioneer Hi-Bred, a DuPont business, which according to a 58-page lawsuit alleges that Pioneer’s practices in the farming of genetically modified seed crops on fields next to Waimea unlawfully allowed pesticides and pesticide-laden fugitive dust to blow into 100 residents’ homes on almost a daily basis for more than 10 years.[33]

DuPont contributed $4 million to oppose the passage of California Proposition 37, which would mandate the disclosure of genetically modified crops used in the production of California food products.[34][35][36] Pioneer Hi-Bred, a DuPont business, manufactures genetically modified seeds, other tools, and agricultural technologies used to increase crop yield.

Recognition

DuPont has been awarded the National Medal of Technology four times: first in 1990, for its invention of "high-performance man-made polymers such as nylon, neoprene rubber, "Teflon" fluorocarbon resin, and a wide spectrum of new fibers, films, and engineering plastics"; the second in 2002 "for policy and technology leadership in the phaseout and replacement of chlorofluorocarbons". Additionally, DuPont scientist George Levitt was honored with the medal in 1993 for the development of sulfonylurea herbicides—environmentally friendly herbicides for every major food crop in the world. In 1996, DuPont scientist Stephanie Kwolek was recognized for the discovery and development of Kevlar.

On the company's 200th anniversary in 2002, it was presented with the Honor Award by the National Building Museum in recognition of DuPont's "products that directly influence the construction and design process in the building industry."[37]

Controversies

Behind the Nylon Curtain

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2011) |

In 1974, Gerard Colby Zilg, wrote Du Pont: Behind the Nylon Curtain, a critical account of the role of the DuPont family in American social, political and economic history. The book was nominated for a National Book Award in 1974.

A du Pont family member obtained an advance copy of the manuscript and was "predictably outraged". A DuPont official contacted The Fortune Book Club and stated that the book was "scurrilous" and "actionable" but produced no evidence to counter the charges. The Fortune Book Club (a subsidiary of the Book of the Month Club) reversed its decision to distribute Zilg's book. The editor-in-chief of the Book of the Month Club declared that the book was "malicious" and had an "objectionable tone". Prentice Hall removed several inaccurate passages from the page proofs of the book, and cut the first printing from 15,000 to 10,000 copies, stating that 5,000 copies no longer were needed for the book club distribution. The proposed advertising budget was reduced from $15,000 to $5,500.[38]

Zilg sued Prentice Hall (Zilg v. Prentice Hall), accusing it of reneging on a contract to promote sales.

The Federal District Court ruled that Prentice Hall had "privished" the book (the company had conducted an intentionally inadequate merchandising effort) and breached its obligation to Zilg to use its best efforts in promoting the book because the publisher had no valid business reason for reducing the first printing or the advertising budget. The court also ruled that the DuPont Company had a constitutionally protected interest in discussing its good faith opinion of the merits of Zilg's work with the book clubs and the publisher, and found that the company had not engaged in threats of economic coercion or baseless litigation.[38]

The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit overturned the damages award in September 1983. The court stated that, while DuPont's actions "surely" resulted in the book club's decision not to distribute Zilg's work and also resulted in a change in Prentice Hall's previously supportive attitude toward the book, DuPont's conduct was not actionable. The court further stated that the contract did not contain an explicit "best efforts" or "promote fully" promise, much less an agreement to make certain specific promotional efforts. Printing and advertising decisions were within Prentice Hall's discretion.

Zilg lost a Supreme Court appeal in April 1984.

In 1984 Lyle Stuart re-released an extended version, Du Pont Dynasty: Behind the Nylon Curtain.[39]

Genetically engineered foods

A lawsuit filed against Pioneer Hi-Bred, a DuPont business, alleging that Pioneer's practices in the production of genetically modified seed crops on fields next to Waimea unlawfully allowed pesticides and pesticide-laden fugitive dust to blow into 100 residents' homes on almost a daily basis for more than 10 years.[33]

DuPont contributed $4 million to oppose the passage of California Proposition 37, which would mandate the disclosure of genetically modified crops used in the production of California food products.[34]

Chlorofluorocarbons

DuPont, along with Thomas Midgley working under Charles Kettering of General Motors, was the inventor of CFCs (chlorofluorocarbons). CFCs are ozone-depleting chemicals that were used primarily in aerosol sprays and refrigerants. DuPont was the largest CFC producer of in the world with a 25% market share in the 1980s.

In 1974, responding to public concern about the safety of CFCs,[40] DuPont promised to stop production of CFCs should they be proven to be harmful to the ozone layer. On March 4, 1988, U.S. Senators Max Baucus (D-Mont.), David Durenberger (R-Minn.), and Robert T. Stafford (R-Vt.) wrote to DuPont, in their capacity as the leadership of the Congressional subcommittee on hazardous wastes and toxic substances, asking the company to keep its promise to completely stop CFC production (and to do so for most CFC types within one year) in light of the 1987 international Montreal Protocol for the global reduction of CFCs. The Senators argued that “DuPont has a unique and special obligation” as the original developer of CFCs and the author of previous public assurances made by the company regarding the safety of CFCs. DuPont announced that it would begin leaving the CFC business after a March 15, 1988 NASA announcement that CFCs were not only creating a hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica, but also thinning the layer elsewhere in the world. In 1992, DuPont announced its intention to stop selling CFCs as soon as possible, and no later than year end 1995.[41]

DuPont maintains the company took the initiative in phasing out CFCs[42] and in replacing CFCs with a new generation of refrigerant chemicals, such as HCFCs and HFCs.[43] In 2003, DuPont was awarded the National Medal of Technology, recognizing the company as the leader in developing CFC replacements.

PFOA (C8)

DuPont has faced fines from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and litigation over releases of the Teflon-processing aid perfluoro-octanoic acid (PFOA, also known as C8) from their works in Washington, West Virginia.[44] PFOA-contaminated drinking water led to increased levels in the bodies of residents in the surrounding area. The court-appointed C8 Science Panel is investigating "whether or not there is a probable link between C8 exposure and disease in the community."[45] The C8 Science Panel started releasing data in October 2008 and linked high cholesterol, but not diabetes, to exposure.[46] DuPont has also faced U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings from the shareholder group DuPont Shareholders for Fair Value over the company's transparency regarding the chemical.[47]

DuPont has agreed to sharply reduce its output of PFOA,[48] and was one of eight companies to sign on with the USEPA's 2010/2015 PFOA Stewardship Program. The agreement calls for the reduction of "facility emissions and product content of PFOA and related chemicals on a global basis by 95 percent no later than 2010 and to work toward eliminating emissions and product content of these chemicals by 2015."[49]

Tax avoidance and lobbying

In December 2011, the non-partisan organization Public Campaign criticized DuPont for spending $13.75 million on lobbying and not paying any taxes during 2008–2010, instead getting $72 million in tax rebates, despite making a profit of $2.1 billion, and increasing executive pay by 188% to $27.4 million in 2010 for its top 5 executives.[50]

Imprelis

In October 2010 DuPont began marketing a pesticide called Imprelis, for control of certain plants in turf areas. It had the unintended effect of killing certain evergreen tree species and was recalled.[51]

NASCAR sponsorship

DuPont is widely known for its sponsorship of NASCAR driver Jeff Gordon and his Hendrick Motorsports No.24 Chevrolet SS. DuPont has been sponsoring Jeff Gordon since he began in Sprint Cup (then Winston Cup) in 1992. DuPont has said this about their sponsorship:

Our sponsorship of Jeff Gordon helps keep DuPont brands and products in the public eye. Branding is a key component of the DuPont knowledge intensity strategy for achieving sustainable growth.[52]

The partnership lasted 18 seasons before DuPont was replaced by the AARP Drive to End Hunger as the No. 24 team's primary sponsor. DuPont continued as associate sponsor with a 12-race deal,[53] though the deal was extended to 14 races after DuPont's rebranding as Axalta.[21]

See also

- Du Pont family

- DuPont v. Kolon Industries

- Hagley Museum and Library

- Longwood Gardens

- Krebs Pigments and Chemical Company

- Protein and Fermentative Microorganism Development

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e "2010 Form 10-K, E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company". United States Securities and Exchange Commission.

- ^ "2012 press release". United Business Media.

- ^ "The DuPont Company". Delaware Historical Society. Retrieved March 29, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Davis, William C., Jr. Handloading (1981) National Rifle Association ISBN=0-935998-34-9 pp.31–33

- ^ "Farming with Dynamite - A few hints to farmers"

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.619

- ^ "Hosiery Woes" Business Week, February 7, 1942, pp. 40–43

- ^ "Nylon in Tires", Scientific American, August 1943, p 78

- ^ Starkey, Jonathan (June 12, 2011). "DuPont pays no tax on $3B profit, and it's legal". The News Journal. New Castle, Delaware. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2011.

- ^ DuPont–Company at a Glance. Retrieved on March 29, 2006

- ^ "Fortune 500: 1955–2005". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "US Approves DuPont Plenish Soybeans - Farm Chemicals International Website - Farm Chemicals International - Article". Farm Chemicals International. June 8, 2010. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Replacing Trans Fat | March 12, 2012 Issue - Vol. 90 Issue 11 | Chemical & Engineering News". Cen.acs.org. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ "Two Centuries of Process Safety at DuPont | James A. Klein, E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company |" (PDF).

- ^ Jonathan Starkey (April 21, 2011). "DuPont quarterly profit up 27%". News Journal. Wilmington, Delaware: Gannett. Business. Retrieved April 22, 2011.

DuPont, the world's largest producer of titanium dioxide, produces the pigment at the Edge Moor manufacturing facility, primarily for the paper industry.

- ^ America's Top 10 Most-Polluted Waterways | Mother Jones

- ^ DuPont Knowledge Center in Hyderabad, India, Opens today[dead link]

- ^ "DuPont to Acquire Danisco for $6.3 billion – WILMINGTON, Del., Jan. 9, 2011 /PRNewswire/ –". prnewswire.com. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- ^ "DuPont Successfully Completes Tender Offer for Danisco – Yahoo! Finance". finance.yahoo.com. Retrieved May 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Bromberg, Nick (February 4, 2013). "Jeff Gordon's DuPont No. 24 will be changing in 2013". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ "2009 SEC 10-K". Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ^ "Spruance Site: About Our Plant". Dupont. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

"2008 Dupont: CEFIC European Responsible Care Award 2008: Application Form". European Chemical Industry Council. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

"United States Securities and Exchange Commission: Form 10-K" (PDF). Analist.nl Nederland/Hoofdkantoor. 2008. pp. 10–11. Retrieved January 16, 2010. - ^ "DuPont News Releases". onlinepressroom.net. 2011 [last update]. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "DuPont: Investor Center – News Release". phx.corporate-ir.net. Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ^ "DuPont names Ellen Kullman as chair – MarketWatch". marketwatch.com. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ "DuPont's Board of Directors Appoints Ellen Kullman Chair". prnewswire.com. Retrieved November 6, 2009.

- ^ Unknown Author (December 6, 2005). "DuPont Tops BusinessWeek Ranking of Green Companies". GreenBiz News.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Green Leaders Show The Way Business Week

- ^ "State’s DuPont Nature Center at Mispillion Harbor Reserve Opens"[dead link]

- ^ "DuPont Nature Center Dedicated in Delaware"[dead link]

- ^ Political Economy Research Institute Toxic 100 retrieved Aug 13, 2007

- ^ a b Vanessa, Van Voorhis (December 13, 2012). "Waimea residents sue Pioneer - GMO SEED COMPANY FACING 'SUBSTANTIAL' LAWSUIT". San Diego Reader. Cite error: The named reference "Garden Island Newspaper" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b Westervelt, Amy (August 22, 2012). "Monsanto, DuPont Spending Millions to Oppose California's GMO Labeling Law". Cite error: The named reference "Forbes" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Behrsin, Pamela (August 22, 2012). CA Prop. 37 - GMO Labeling: Funding Update - Monsanto ($4M), Dupont ($4M), Pepsi ($1.7M) (Report).

- ^ Rice, Dave (September 4, 2012). "Public Sparring Between Prop 37 Supporters, Opponents Begins". San Diego Reader.

- ^ "A Salute to DuPont" (Press release). National Building Museum. April 11, 2002.

- ^ a b "Gerard Colby ZILG, Plaintiff-Appellee-Cross-Appellant vs.PRENTICE-HALL, INC., Defendant-Appellant and E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., Inc., Defendant-Cross-Appellee"

- ^ Unknown Author (April 17, 1984). "High Court Rebuffs Author". The New York Times: Section C, Page 16, Column 1.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Flaherty, Francis J. (April 2, 1984). "Authors Fighting for 'Voice in the Process'". The National Law Journal: 26.; Unknown Author (1984). "Federal Court of Appeals reverses award of damages to author Gerard Zilg in his breach of contract action against Prentice-Hall; District Court's dismissal of Zilg's action against E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company for tortious interference with contractual relations is affirmed". Entertainment Law Reporter. 5 (11).{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help); Slung, Michele (October 9, 1983). ""Privish" and Perish". The Washington Post: 15. - ^ DuPont Refrigerants–History Timeline, 1970. (URL accessed March 29, 2006).

- ^ Unknown Author (April 27, 1992). "The World is Phasing Out CFCs, It Won't Be Easy" ( – 27, 1992&as_yhi=April 27, 1992&btnG=Search Scholar search). The New York Times: A7.

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help); External link in|format= - ^ DuPont Refrigerants– History Timeline, 1980. (URL accessed March 29, 2006).

- ^ US EPA: Ozone Depletion Glossary. (URL accessed March 29, 2006).

- ^ Clapp, Richard; Hoppin, Polly; Jagai, Jyotsna; Donahue, Sara: "Case Studies in Science Policy: Perfluorooctanoic Acid" Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy (SKAPP). Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ C8 Science Panel: "The Science Panel" Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ Scott Finn: "C8 study shows link with high cholesterol" West Virginia Public Broadcasting (October 16, 2008). Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ United Steelworkers: "DuPont Shareholders for Fair Value Calls on SEC to Investigate DuPont" 2005 Releases and Advisories. (May 24, 2005). Accessed October 25, 2005.archive

- ^ Renner, Rebecca: "Scientists hail PFOA reduction plan" Environmental Science & Technology Online. Policy News. (March 25, 2005). Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ USEPA: "2010/15 PFOA Stewardship Program" Accessed October 25, 2008.

- ^ Portero, Ashley. "30 Major U.S. Corporations Paid More to Lobby Congress Than Income Taxes, 2008–2010". International Business Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2011. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ^ Detroit Free Press, May 21, 2012, page A1

- ^ "Sponsors". Jeffgordon.com. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- ^ Newton, David (October 28, 2010). "Jeff Gordon has 3-year sponsorship deal". ESPN. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- Further reading

- Arora, Ashish Ralph Landau and Nathan Rosenberg, (eds). (2000). Chemicals and Long-Term Economic Growth: Insights from the Chemical Industry.

- Chandler, Alfred D. (1971). Pierre S. Du Pont and the making of the modern corporation.

- Chandler, Alfred D. (1969). Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise.

- du Pont, B.G. (1920). E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company: A History 1802–1902. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. – (Kessinger Publishing Rare Reprint. ISBN 1-4179-1685-0).

- Grams, Martin. The History of the Cavalcade of America: Sponsored by DuPont. (Morris Publishing, 1999). ISBN 0-7392-0138-7

- Haynes, Williams (1983). American chemical industry.

- Hounshell, David A. and Smith, John Kenly, JR (1988). Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R and D, 1902–1980. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32767-9.

- Kinnane, Adrian (2002). DuPont: From the Banks of the Brandywine to Miracles of Science. Willimington: E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company. ISBN 0-8018-7059-3.

- Ndiaye, Pap A. (trans. 2007). Nylon and Bombs: DuPont and the March of Modern America

- Zilg, Gerard Colby "DuPont: Behind the Nylon Curtain" (Prentice-Hall: 1974) 623 pages.

External links

- Corporate History as presented by the company

- DuPont Website

- Yahoo company profile: E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company

- DuPont/MIT Alliance

- The Stocking Story: You Be The Historian, Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

- The DuPont Company on the Brandywine A digital exhibit produced by the Hagley Library that covers the company's founding and early history

- Articles with dead external links from June 2008

- Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- 1802 establishments in the United States

- Chemical companies of the United States

- Companies based in New Castle County, Delaware

- Companies established in 1802

- DuPont

- Companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Engineering companies of the United States

- Nanotechnology companies

- National Medal of Technology recipients

- Chemical companies

- Multinational companies headquartered in the United States

- Price fixing convictions