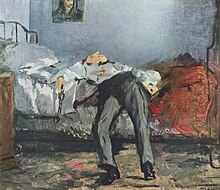

Suicide

| Suicide |

|---|

Suicide (from Latin sui caedere, to kill oneself) is the act of willfully ending one's own life. Suicide is sometimes used as a noun for one who has committed or attempted the act.

The terminology and its implications

Suicide can be stigmatized or honored, depending on cultural context and its apparent reasons. Those experiencing suicidal ideation, or thoughts about fatally harming one's self, may struggle to be heard and understood, or might be people who willfully ignore others. The person feeling suicidal may often be made to feel rejected and guilty by those they have confided their thoughts and feelings to - sometimes even by mental health professionals - accusing them of trying to hurt the feelings of the friends or family they just confided to, or of making suicide 'threats', or they might indeed be attempting to manipulate others. This can lead to situations wherein relatives and friends of a person who committed suicide without telling anyone then proceed to question why the person never told them. Suicidal ideation may result from the experience of emotional pain outweighing the individual's coping strategies and resources for dealing with that pain (leftist view) or from an individual's unwillingness to impose self-discipline and care about others more than him or herself (right-wing view).

The perception of suicide is highly varied between the cultures, religions and legal and social systems of the world. It is considered a sin or immoral act in many religions, and a crime in some jurisdictions, such as Singapore. On the other hand, some cultures have viewed it as an honorable way to exit certain shameful or hopeless situations. Persons attempting or dying by suicide sometimes leave a suicide note.

Strictly, suicide is defined thusly: the death of the person who commits suicide must be the central component and only intention of the act, rather than a secondary consequence of an act which is centrally motivated by religion, politics, etc.; hence, suicide bombing is considered a kind of bombing rather than a kind of suicide, and martyrdom usually escapes religious or legal proscription. Generally, there are only legal consequences when there is death and proof of intent. However, not all follow this narrower definition. Certainly, a suicide bomber knows that death will be part of the outcome of his or her actions.

Defined as above, acts of suicide are necessarily committed only by human beings. No other known healthy organism possesses both the will and the capability to intentionally terminate its own life for the sole sake of death.[1]

Medical views on suicide

Modern medicine treats suicide as a mental health issue. Overwhelming suicidal thoughts are considered a medical emergency. Medical professionals advise that people who have expressed plans to kill themselves be encouraged to seek medical attention immediately. This is especially true if the means (weapons, drugs, or other methods) are available, or if the patient has crafted a detailed plan for executing the suicide. Special consideration is given to trained personnel to look for suicidal signs in patients. Depressive people are considered a high-risk group for suicidal behaviour. Suicide hotlines are widely available for people seeking help.

Methods

Much literature is available to the would-be suicide explaining the pros and cons of any particular method. The principal methods would seem to be: toxification (i.e. overdose), asphyxiation (i.e. hanging), bloodletting (slitting ones wrists), shooting, blunt force trauma (jumping into a valley from a bridge, stepping in front of a train).

Suicide as a form of defiance and protest

Heroic suicide, for the greater good of others, is often celebrated. For instance, Mahatma Gandhi went on a hunger strike to prevent fighting between Hindus and Muslims, and, although he was stopped before dying, it appeared he would have willingly succumbed to starvation. For this, he earned the respect of many.

In the 1960s, Buddhist monks, most notably Thích Quảng Đức, in South Vietnam gained Western praise in their protests against President Ngô Đình Diệm by burning themselves to death. Similar events were reported in eastern Europe, such as the death of Jan Palach following the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In wars, there have been numerous reports of combatants performing suicidal acts in order to save other soldiers. Not everybody would count all these actions as suicides, as the person's death was clearly not the primary purpose. Opponents argue that these people would probably achieve a comparable result by spending the rest of their lives in active struggle.

Hunger strikes have frequently been used as a form of protest by incarcerated persons, and result in death where neither side in the strike gives way.

Military Suicide

In the desperate final days of World War II, many Japanese pilots volunteered for kamikaze missions in a last attempt to forestall defeat for the Empire. The degree to which these pilots were engaging in heroic, selfless action or whether they faced immense social pressure is a matter of historical debate. The Japanese also built one-man "human torpedo" suicide submarines. However, suicide has been fairly common in warfare throughout history. Soldiers and civilians committed suicide to avoid capture and slavery (including a wave of German and Japanese suicides in the last days of World War II). Commanders committed suicide rather than accept defeat. Behavior that could be seen as suicidal occurred often in battle. For instance, soldiers under cannon fire at the Battle of Waterloo took fatal hits rather than duck and place their comrades in harm's way. The Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War, Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg in the US Civil War, and the charge of the French cavalry at Sedan in the Franco-Prussian War were assaults that continued even after it was obvious to participants that the attacks were unlikely to succeed and would probably be fatal to most of the attackers. Japanese infantrymen usually fought to the last man, launched "banzai" suicide charges and committed suicide during the Pacific island battles in World War II. In Saipan, Okinawa, civilians joined in the suicides. Suicidal attacks by pilots were common in the 20th century: the attack by U.S. torpedo planes at the Battle of Midway was very similar to a kamikaze attack. Argentinian fighter pilots made suicide attacks on British ships during the Falklands War in 1982.

This particular reference to suicide is also what leads to the everyday usage of the term when indicating a hopeless situation, often in business, such as "it would be suicide for us to go to market without a viable product."

Debate over suicide

There are arguments in favor of allowing an individual to choose between life and suicide. This view sees suicide as a valid option and a human right. This line rejects the widespread belief that suicide is always or usually irrational, saying instead that it is a genuine, albeit severe, solution to real problems – a line of last resort that can legitimately be taken when the alternative is considered worse. No being should be made to suffer unnecessarily, and suicide provides an escape from suffering in certain circumstances, such as incurable disease and old age. These theories are most commonly held in Continental Europe, where euthanasia and other such topics are discussed in parliament, unlike the US, with its strong Christian tradition.

Similarly, a young and healthy person, free from any major trauma in their past, in their opinion free from any mental disorders, and with a future even regarded as bright by observers, can come to the decision that they don't find life rewarding and that they wish to end their experience then and there. This is usually met with a negative reaction, and these persons are often persuaded from their feelings and beliefs, while others choose to disregard such pressures. Those who ultimately kill themselves under these circumstances might argue that the peace of nothingness they expect to find in death, if they are not religious, or the peace of heaven offered to the dead by a deity whose forgiveness they trust in, is much more appealing than the experiences they expect to have in this world. They may feel too eager for this better state of (non-)existence to wait, especially during modern times in which the human lifespan is progressively increasing.

In the past, the Japanese were sometimes ordered by their superiors to commit seppuku, a form of ritual disembowelment suicide. This was expected as a matter of honor where staying alive committed a greater dishonor to their family. They may also have done it as a matter of free choice, also for the sake of honor, and it was considered better than being taken prisoner. Achieving a placid indifference to life or death was considered a state of enlightenment in certain Buddhist traditions.

Epidemiology

According to official statistics, about a million people commit suicide annually, more than those murdered or killed in war. [2]. As for 2001 in the USA, suicides outnumber homicides by 3 to 2 and deaths from AIDS by 2 to 1 [3] However, it is probable that the incidence of suicide is under-reported due to both religious and social pressures.

Many theories have been developed to explain the causes of suicide with no strong consensus with one. Nevertheless, from the known suicides, certain trends are apparent:

Gender and suicide: In the Western world, males die much more often than females by suicide, while females attempt suicide more often. Some medical professionals believe this is due to the fact that males are more likely to end their life through violent means (guns, knives, hanging, drowning, etc.), while women primarily overdose on medications. Others ascribe the difference to inherent differences in male/female psychology, with men having more of an operational mindset and women being more aware of social nuance. In any case, violent suicide attempts are much more likely to be successful. [4] Typically males die from suicide three to four times as often as females.

Excess male mortality from suicide is also evident from data from non-western countries. In 1979-81, the number of countries with a non-zero suicide rate was 74. Two of these reported equal rates for the sexes: Seychelles and Kenya. Three countries reported female rates exceeding male rates: Papua-New Guinea, Macao, French Guiana. The remaining 69 countries had male suicide rates greater than female suicide rates. [5]

Barraclough found that the female rates of those aged 5-14 equaled or exceeded the male rates only in 14 countries, mainly in South America and Asia. [6]

National suicide rates sometimes tend to be stable. For example, the 1975 rates for Australia, Denmark, England, France, Norway, and Switzerland, were within 3.0 per 100,000 of population from the 1875 rates (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1983; Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 21). The rates in 1910-14 and in 1960 differed less than 2.5 per 100,000 of population in Australia, Belgium, Denmark, England & Wales, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Norway, Scotland, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and The Netherlands (Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 22).

There are considerable differences between national suicide rates. Findings from two studies showed a range from 0.0 to more than 40 suicides per 100,000 of population. [7]

National suicide rates, apparently universally, show an upward secular trend. This trend has been well documented for European countries. [8] The trend for national suicide rates to rise slowly over time might be an indirect result of the gradual reduction in deaths from other causes. Falling death rates from causes other than suicide uncover hidden suicide predisposition. This uncovering effect is due to suicide, up to now, not being preventable. [9] [10] Consistent with this interpretation, between 1971 and 1991, the Australian male suicide rate was rising while the overall mortality rate for Australian males was falling [11]

Race and suicide. At least in the USA, whites commit suicide more often than blacks do. This is true for both genders. Non-Hispanic whites are nearly 2.5 times more likely to kill themselves as blacks or Hispanics. [12]

Age and suicide At least in the USA, males over 70 commit suicide more often than younger males. There is no such trend for females. Older non-Hispanic white men are much more likely to kill themselves than older men or women of any other group, which contributes to the relatively high suicide rate among whites. White men in their 20s, conversely, kill themselves only slightly more often than black or Hispanic men in the same age group.

Season and suicide People commit suicide more often during spring and summer. The idea that suicide is more common during the winter holidays (including Christmas in the northern hemisphere) is actually a myth.[13]

Combination of homicide and suicide

Since crime just prior to suicide is often perceived as being without consequences, it is not uncommon to combine homicide with suicide. Motivations may range from guilt, to evading punishment, to insanity, to killing others as part of a suicide pact.

Attempted suicide and parasuicide

Many suicidal people participate in suicidal activities which do not result in death. These activities fall under the designation attempted suicide or parasuicide. Generally, those with a history of such attempts are almost 23 times more likely to eventually end their own lives than those without.[14]

Sometimes, a person will make actions resembling suicide attempts while not being fully committed, or in a deliberate attempt to have others notice. This is called a suicidal gesture (also known as a "cry for help"). Prototypical methods might be a non-lethal method of self-harm that leaves obvious signs of the attempt, or simply a lethal action at a time when the person considers it likely that they will be rescued or prevented from fully carrying it out.

On the other hand, a person who genuinely wishes to die may fail, due to lack of knowledge about what they are doing; unwillingness to try methods that may end in permanent damage if they fail or harm to others; or an unanticipated rescue, among other reasons. This is referred to as a suicidal attempt.

Distinguishing between a suicidal attempt and a suicidal gesture may be difficult. Intent and motivation are not always fully discernible since so many people in a suicidal state are genuinely conflicted over whether they wish to end their lives. One approach, assuming that a sufficiently strong intent will ensure success, considers all near-suicides to be suicidal gestures. This however does not explain why so many people who fail at suicide end up with severe injuries, often permanent, which are most likely undesirable to those who are making a suicidal gesture. Another possibility is those wishing merely to make a suicidal gesture may end up accidentally killing themselves, perhaps by underestimating the lethality of the method chosen or by overestimating the possibility of external intervention by others. Suicide-like acts should generally be treated as seriously as possible since if there is an insufficiently strong reaction from loved ones from a suicidal gesture, this may motivate future, more committed attempts.

In the technical literature the use of the terms parasuicide, or deliberate self-harm (DSH) are preferred – both of these terms avoid the question of the intent of the action.

An important difference to note is that self-harm is not a suicide attempt. There is a non-causal correlation between self-harm and suicide; individuals who suffer from depression or other mental health issues are also more likely to choose suicide. DSH is far more common than suicide, and the majority of DSH participants are females aged under 35. They are usually not physically ill and while psychological factors are highly significant, they are rarely clinically ill and severe depression is uncommon. Social issues are key – DSH is most common among those living in overcrowded conditions, in conflict with their families, with disrupted childhoods and history of drinking, criminal behavior, and violence. Individuals under these stresses become anxious and depressed and then, usually in reaction to a single particular crisis, they attempt to harm themselves. The motivation may be a desire for relief from emotional pain or to communicate feelings, although the motivation will often be complex and confused. DSH may also result from an inner conflict between the desire to end life and the desire to continue living. See the article on self-harm for an in depth discussion.

Distinction between suicide and attempted suicide

An important distinction has also been made (see Erwin Stengel, 'Suicide and Attempted Suicide') between those who kill themselves and did not mean to, and those who did not kill themselves but did mean to. Thus a 'Suicide' (noun) may either succeed or fail in his/her goal (i.e. succeed in killing himself/herself or not) and an 'Attempted Suicide' (noun) may either succeed or fail in his/her goal (e.g., succeed in 'making a cry for help' or fail and, in doing so, probably die).

This distinction, if correctly drawn, can have important ramifications for the treatment of people who are suicidal. Its definition is when one takes their own life, in other words when a person kills himself or herself. Some people are suicidal and there are many “symptoms” that we can be observant of that can assist us in picking out those who are contemplating suicide. Some of these include a person who has a number of problems in their life which they think have no solution, a person becoming abnormally violent, depressed, becoming drawn to themselves, etc. Some people turn to other means whilst trying to deal or overcome their irrational thoughts and behavior, this might include the consumption of drugs, alcohol, etc. and as a result, their problem only ends up getting worse than it originally was. Most people, who try and commit suicide but fail in doing so, very often try again. This is why it is so important to identify these suicidal people before it’s too late. Statistics have shown that 4 in every 10 people, who think about suicide, finally do commit. The suicide rate in teenagers is on the increase and governments all around the world are trying to combat this. Most countries have introduced special facilities such as “the lifeline” which is aimed at helping those who are at the brink of suicide. There are also workshops, which are being carried out and have the same aim. In these workshops, you can speak to trained professionals and motivational speakers who will do all that are possible to help you.

Suicide in literature

Suicide has been used as a dramatic plot element in a number of literary works, such as The Virgin Suicides, The Sorrows of Young Werther, The Bell Jar, Madame Bovary, The Sound and the Fury, Anna Karenina, Demons, Everything is Illuminated, A Perfect Day for Bananafish, Umberto D, The Awakening, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, Death of a Salesman, Groundhog Day, Million Dollar Baby, Macbeth, Stranger in a Strange Land, The Shawshank Redemption, The Juggler, Chushingura, Burmese Days, The Great Gatsby, Veronika Decides to Die, The Driver's Seat and Survivor. Robert E. Howard wrote several poems, including The Tempter, about suicide.

References

- ^ Doug (SDSTAFF) (2001-02-01). "Does any animal besides humans commit suicide?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 2006-04-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Suicide prevention". WHO Sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. February 16, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ "Teen Suicide Statistics". Adolescent Teenage Suicide Prevention. FamilyFirstAid.org. 2001. Retrieved 2006-04-11.

- ^ Cantor CH. Suicide in the Western World. In: Hawton K, van Heering K, eds. International handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2000: 9-28.

- ^ Lester, Patterns, Table 3.3, pp. 31-33

- ^ Barraclough,B M. Sex ratio of juvenile suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1987, 26, 434-435.

- ^ La Vecchia, C., Lucchini, F., & Levi, F. (1994) Worldwide trends in suicide mortality, 1955-1989. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 90, 53-64.; Lester, Patterns, 1996, pp. 28-30.

- ^ Lester, Patterns, 1996, p. 2.

- ^ Baldessarini, R. J., & Jamison, K. R. (1999) Effects of medical interventions on suicidal behavior. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60 (Suppl. 2), 117-122.

- ^ Khan, A., Warner, H. A., & Brown, W. A. (2000) Symptom reduction and suicide risk in patients treated with placebo in antidepressant clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 311-317.

- ^ Jain, 1994, p. 18

- ^ [1] Template:PDFlink

- ^ "Questions About Suicide". Centre For Suicide Prevention. 2006.

- ^ Shaffer, D.J. (1988). "The Epidemiology of Teen Suicide: An Examination of Risk Factors". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 49 (supp.): 36–41. PMID 3047106.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

See also

- Cult suicide

- Suicide attack

- Seppuku (Harakiri)

- Dutiful suicide

- List of suicides

- List of songs about suicide

- Meaning of life

- The choking game

- Quantum suicide

- Self-harm

- Suicide Act 1961

- Terminal illness

- Suicide booth

- Suicider

- Mass suicide

- alt.suicide.holiday

- Suicide (book)

Further reading

Documents and periodicals

- Frederick, C. J. Trends in Mental Health: Self-destructive Behavior Among Younger Age Groups. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse. 1976. ED 132 782.

- Lipsitz, J. S., Making It the Hard Way: Adolescents in the 1980s. Testimony presented to the Crisis Intervention Task Force of the House Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families. 1983. ED 248 002.

- McBrien, R. J. "Are You Thinking of Killing Yourself? Confronting Suicidal Thoughts." SCHOOL COUNSELOR 31 (1983): 75–82.

- Ray, L. Y. "Adolescent Suicide." Personnel and Guidance Journal 62 (1983): 131–35.

- Rosenkrantz, A. L. "A Note on Adolescent Suicide: Incidence, Dynamics and Some Suggestions for Treatment." ADOLESCENCE 13 (l978): 209–14.

- Suicide Among School Age Youth. Albany, NY: The State Education Department of the University of the State of New York, 1984. ED 253 819.

- Suicide and Attempted Suicide in Young People. Report on a Conference. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1974. ED 162 204.

- Teenagers in Crisis: Issues and Programs. Hearing Before the Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families. House of Representatives Ninety-eighth Congress, First Session. Washington, DC: Congress of the U. S., October, 1983. ED 248 445.

- Smith, R. M. Adolescent Suicide and Intervention in Perspective. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the National Council on Family Relations, Boston, MA, August, 1979. ED 184 017.

Nonfiction books

- Bongar, B. The Suicidal Patient: Clinical and Legal Standards of Care. Washington, D.C.: APA. 2002. ISBN 1557987610

- Jamison, Kay Redfield (2000). Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide. Vintage. ISBN 0375701478.

- Stone, Geo. Suicide and Attempted Suicide: Methods and Consequences. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001. ISBN 0-7867-0940-5

- Humphry, Derek. Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. Dell. 1997.

- Joiner, Thomas E. (2006). Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

External links

Crisis lines

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-TALK (8255) - a 24-hour toll-free suicide prevention helpline, United States

- Suicide Prevention Center, Los Angeles - a 24-hour suicide prevention helpline, toll-free in LA Country, United States

- Suicide Hotlines - listing of suicide prevention lines in the United States and around the world. Look here to find a crisis line near you.

- The Trevor Helpline: 1 866 - 4U TREVOR - nationwide, 24-hour, free, confidential suicide helpline for gay and questioning teenagers, United States. See The Trevor Project article.

Support groups

- Samaritans (UK) - 24-hour support help, United Kingdom

- #alt.suicide.bus.stop (ASBS) - a support group for the suicidal, by the suicidal

- Befrienders Worldwide - information about suicide for most countries

- The Suicide Forum - a support forum for people in crisis

- SuicideTalk.com Suicide forums (Inactive as of 3 May 2006)

- Open Directory Project: Mental Health: Disorders: Suicide: "'Support Groups'" - support groups for suicidal people

Suicide prevention

- [2] - American Foundation for Suicide Prevention

- metanoia.org/suicide - suicide prevention page

- "Understanding and Helping the Suicidal Person" - information on suicide prevention

- TeenSuicide.us - teenage suicide prevention information

- Choose Life - suicide prevention in Scotland

- The Debate: a pro-choice FAQ

- Teenage Suicide: Identification, Intervention and Prevention - discussion of teenage suicide prevention

- Suicide and the Exceptional Child - discussion of suicide prevention in children

- Suicide and Sudden Loss: Crisis Management in the Schools - discussion of suicide prevention in schools

Other links

- "Suicide as a Moral Alternative" - discussion on the morality of suicide, including arguments for and against

- "Suicide" in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- cbel.com/suicide/ - directory of information on suicide

- American Association of Suicidology - statistics and general information

- Suicide & Euthanasia - a Biblical Perspective - discussion of suicide from a biblical perspective

- "The Murder of Oneself" - ethical and legal considerations in suicide and its prevention

- "Lithuania's Suicide Epidemic" - article on the high suicide rates of Lithuania

- Suicide Promotion (Internet) - United Kingdom Parliamentary debate - debate by politicians on suicide, 25 January 2005

- Suicide - Frequently Asked Questions

- "Our Right to Suicide" (PDF) - report on the individual's right to die

- Suicide & the Self(PDF) - thesis for a philosophy Masters

- Online Education on Suicide Prevention for Professionals - list of courses for medical professionals