Bengal Sultanate

Sultanate of Bengal শাহী বাংলা[1] شاهی بنگال | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1342–1538 1555–1576 | |||||||||||||||||

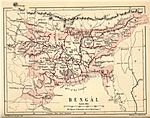

The empire of the Bengal Sultanate in 1500, during the reign of Sultan Alauddin Hussain Shah | |||||||||||||||||

| Status | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gaur Pandua Sonargaon | ||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Bengali (spoken) Persian (court and diplomatic language) Arabic (liturgical) | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (official), Hinduism, Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy, unitary state with federal structure | ||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||

• 1342-1358 | Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah (first) | ||||||||||||||||

• 1572-1576 | Daud Khan Karrani (last) | ||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late medieval | ||||||||||||||||

• Independence declared from Delhi | 1352 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1576 | |||||||||||||||||

| Currency | taka | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

The Bengal Sultanate, officially the Sultanate of Bengal, was a Bengali Muslim state established in the eastern Indian subcontinent on the Bay of Bengal. It was an important power in South and Southeast Asian history.[2][3] Its bordering countries included the Delhi Sultanate, Tibet and Burma. A Bengali-Persianate kingdom,[4] it was known as Shahi Bangla in Bengali and Shahi Bangaleh in Persian, with both terms translating Imperial Bengal.[5][6]

The Bengal Sultanate seceded from the Delhi Sultanate under Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah in 1352 and had capitals in Gaur, Pandua and Sonargaon. Delhi recognized Bengal's independence after it was defeated by Ilyas Shah and his son, Sikandar Shah. The kingdom enjoyed a strategic relationship with Ming China. It reached the height of its power during the reigns of Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah and Alauddin Hussain Shah in the 15th and early 16th centuries, when it controlled most of the eastern subcontinent. Trade links were fostered with the Horn of Africa, the Maldives and Malacca. Its political economy featured the taka as its standard currency. Bengali Muslim architecture flourished under the sultanate's distinct regional genre, incorporating Bengali, Persian and Byzantine elements. A cosmopolitan literary culture developed in the kingdom.

Bengal witnessed immigration from different parts of the Muslim world. Its population also included Hindus and Buddhists. It saw a synthesis of Bengali and Islamic cultures.

In the mid 16th century, Bengal faced the brunt of Sher Shah Suri's conquests. Arakan ended its protectorate relationship with Bengal after allying with the Portuguese Empire. The Mughals defeated the last Sultan, Daud Khan Karrani, in Rajmahal in 1576. Subsequently, eastern Bengal came under the control of the Baro-Bhuyan chieftains. By the 17th century, most of the territories of the sultanate were consolidated into Mughal Bengal. The era of the sultanate had marked the period of Bengal's proper independence.[7] It left an extensive architectural heritage in modern Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal.

History

Bengal was integrated into the Muslim world after the Islamic conquest of the Indian subcontinent. It was annexed by Bakhtiar Khilji as a province of the Delhi Sultanate. In the mid 14th century, governors in Bengal declared independence from the Delhi Sultanate, including at Lakhnauti, Sonargaon and Satgaon. In 1352, the Bengal Sultanate was formed by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah after he conquered the three cities. He also defeated an invasion by the Sultan of Delhi Firuz Shah Tughluq in 1353. Ilyas Shah led successful campaigns against neighboring Hindu states which consolidated the position of the Bengal Sultanate as the foremost military power in the eastern subcontinent. The records of medieval Indian historians, such as Abul Fazl, described him as first Shah of Bengal. His successors formed the Ilyas Shahi dynasty. His son Sikandar Shah and grandson Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah expanded the military, diplomatic and architectural influence of the sultanate.[8]

In 1414, the Hindu noble Raja Ganesha staged a coup and installed his son Jadu on the throne. Jadu later converted to Islam and took the title Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah, reigning until 1433 and proclaiming himself as a caliph of Islam. During his reign, Arakan in Burma came under a century of Bengali suzerainty.[9] His military assisted the Arakanese ruler Narameikhla to regain control of the city of Mrauk U in return for Arakan becoming a vassal state of the Bengal Sultanate. Bengali Muslims formed their own settlements in Arakan. The Buddhist rulers in Arakan received Islamic titles. Coins in Arakan depicted Burmese script on one side and Arabic script on another side.[10]

The Ilyas Shahi dynasty was restored in 1435. It continued to expand the territory of the sultanate, especially towards Northeast India. Palace coups became a regular phenomenon in the kingdom. Between 1487-1494, a group of Abyssinian generals assumed power and ruled the kingdom, taking turns as the Sultan of Bengal.[8]

By the mid 16th-century, the Bengal Sultanate began facing increasing challenges. Between 1539 and 1554, it was overrun by the Afghan Sur Empire of Sher Shah Suri. The Twelve Bhuyan landlords also began asserting their independence. Arakan and Portuguese Chittagong formed the independent Kingdom of Mrauk U.[8]

The Karrani dynasty was the last royal house of the kingdom. Despite the ambitions of its last ruler Daud Khan Karrani, the Bengal Sultanate was abolished by Emperor Akbar of the Mughal Empire after Karrani was defeated in the Battle of Raj Mahal in 1576. Most territories of the sultanate were eventually incorporated into Mughal Bengal.[8]

Geography

The Bengal Sultanate was based in the fertile Bengal delta in eastern part of the Indian subcontinent, which was home to three of the largest rivers in Asia, including the Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna. The three large rivers had as many as 700 tributaries. The climate was tropical, sub-tropical and within the monsoon zone. Its bastion was in the ethno-linguistic region of Bengal proper, divided between modern Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. Its three most recorded administrative centers were Gaur, Pandua and Sonargaon. The first two were located in present-day Maldah District, West Bengal. The latter was located in present-day Sonargaon Upazila, central Bangladesh.

At its peak the sultanate controlled most of the eastern subcontinent, with its territory stretching upto Hoja in the highlands of Assam,[11] the Terai plains of the Himalayan states,[12] Jaunpur in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh,[13] and large parts of the Indian state of Orissa.[13] Tripura and Arakan were under its vassalage.[13]

The sultanate was a located at the apex of the Bay of Bengal.

Monarchy

Bengali Muslim kings and aristocrats relied on traditions developed in the Abbasid Caliphate for statecraft, economy, literary inspiration, architecture, commerce and military doctrines.[14] The Abbasids inherited influences from ancient Persia, Greece, Rome and Byzantium. Muslim rulers combined Abbasid traditions with indigenous Bengali civilization.

The Bengal Sultanate adopted the pre-Islamic Persian tradition of monarchy and statecraft. The customs of its royal courts were modeled on the Sasanian imperial tradition, with a hierarchical bureaucracy and the promotion of Islam as the state-sponsored religious orthodoxy. Foreign envoys to the sultanate's court saw medieval Persianate imperial elements, including peacock feathers, umbrellas, rows of mounted and foot soldiers, a throne designed with precious stones and lavish displays of gold.[14] The Sultan of Bengal carried Persianate imperial titles, including Shah (King) and Shahanshah (King of Kings).[15]

Foreign relations

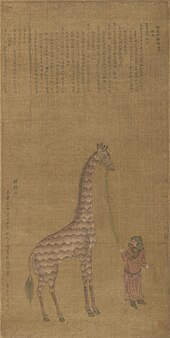

Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah developed relations with the Chinese Ming dynasty, particularly with Emperor Yongle. The two rulers exchanged numerous embassies, including several missions by Chinese envoy Zheng He.[16] Bengal gifted an African giraffe to the Chinese emperor in 1414.[16] On several occasions, Ming China acted as a mediatory between Bengal and its neighboring kingdoms during times of disputes or conflict. Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah developed relations with Shahrukh Mirza of the Timurid Empire and Barsbay of Mamluk Egypt.[17]

Many countries sent embassies to the Bengal Sultanate. They included ambassadors Niccolo De Conti of the Republic of Venice and Ralph Fitch of the Kingdom of England.[18][19]

In the 16th century, the Portuguese Empire engaged with the Bengal Sultans and gained permission to set up trading posts in Chittagong and Satgaon.[20]

Military

Like much of the Persianate world, Bengal relied on imported slave armies.[15] Turks and Abyssinians were enlisted to build the kingdom's defence force and royal guards.[15]

The Bengal Sultanate was the leading military power in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent. It defeated the army of the Delhi Sultanate twice in the 14th century, which forced Delhi to recognize Bengal's independence.[15] Its founder Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah commandeered expeditions as far as Varanasi, Cuttack and the Kathmandu Valley. Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah made Arakan a protectorate. Alauddin Hussain Shah conquered large parts of Assam.

Economy

When Muslim rule was established, Bengal had huge reserves of gold and silver from the pre-Islamic period. A new political economy was established by the Sultans. The taka was introduced as the standard currency of Bengal.[14] The new currency consolidated the legitimacy of the sultanate. A salaried bureaucracy was established. Provincial autonomy manifested in governors and zamindars being allowed to retain shares of land revenue to maintain their own armed forces.[14]

During his two visits to the sultanate, Ibn Battuta described Bengal as a vibrant fertile land overflowing with agricultural commodities.[21] Most of its people were agricultural labourers and textile weavers. The Chinese traveler Ma Huan noted its large shipbuilding industry. Bengali traders were found in Malacca at the time of the sultanate.[22] Shell currency was widely used in the sultanate and imported from the Sultanate of the Maldives in the Indian Ocean.[23] The Maldives received abundant rice supplies in exchange for its cowry shells.[24] During the early part of its reign, the sultanate had a strong trade network with the Horn of Africa, including the Ajuraan sultanate and Ethiopia. Abyssinians were imported through the port of Chittagong. An African giraffe imported by the Bengali Sultan was gifted to the Chinese emperor. However, following the Abyssinian coup of 1486, the sultanate reduced trade relations with Africa.[14]

When Sher Shah Suri conquered Bengal, he extended the Grand Trunk Road to Sonargaon. The road connected the Bengali heartland with Kabul, Samarkand, Bukhara and other parts of Central Asia. Besides its handlooms in silk and cotton muslin, the region exported grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments.

During the reopening of European trade with the East Indies following the Portuguese conquests of Malacca and Goa, Bengal was identified by European traders as "the richest country to trade with".[25]

Immigration

Bengal became a melting pot under the sultanate. Settlers from Persia, Central Asia, Arabia, Abyssinia and North India migrated to Bengal.[26] The port of Chittagong became a busy disembarkation point for migrants from the Middle East and Africa. An important migrant community were Persians, who included mostly teachers, lawyers, scholars and clerics.[27] Migration from Ethiopia and Somalia was suspended after the reign of Abyssinian usurpers ended in 1492.[28]

Administrative centers

The Bengal Sultanate governed its territories through a network of administrative centers known as Mint Towns. These towns hosted a mint which produced the taka.[29] They were district headquarters and contributed to urbanization. They received migrants from other parts of the Muslim world, including North India, Central Asia and the Middle East.

| Mint Town | Modern areas | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lakhnauti | Maldah District and Rajshahi District | The oldest mint town and first capital of the Bengal Sultanate |

| Sonargaon | Dhaka District and Narayanganj District | Capital of several Bengal Sultans and administrative center of East Bengal |

| Satgaon | Hooghly District and Calcutta District | Flourishing port city |

| Chatgaon | Chittagong District | Bengal's largest seaport and administrative center of southeast Bengal |

| Mrauk U | Sittwe District | Administrative center of Arakan |

| Fatehabad | Faridpur District | |

| Khalifatabad | Bagerhat District | Includes Mosque City of Bagerhat |

| Ghiaspur | Mymensingh District | |

| Barbakaabad | Dinajpur District | |

| Sharifabad | Birbhum District | |

| Nusratabad | Rangpur District and Bogra District | |

| Chandrabad | Murshidabad district | |

| Rotaspur | Located in Bihar state, India | |

| Mahmudabad | Nadia District and Jessore District | |

| Jalalabad | Sylhet District | Named after Hazrat Shah Jalal |

| Muzaffarabad | Maldah District | Served as one of the longest capitals of the Bengal Sultanate |

| Husaynabad | 24 Parganas | |

| Tandah | Maldah District | Wartime capital of the last Sultan of Bengal |

Culture

The ruling class of the Bengal Sultanate combined heavy Persianate influences with the rich cultural heritage of Bengal.[30] According to historian Richard M Eaton, the Bengali court was modeled on Iranian tradition.[30] The Sultans were styled as the "King of Kings in the East".[30]

Architecture

The most enduring legacy of the Bengal Sultanate is its architectural heritage. A distinct Bengali-Islamic architecture developed during its reign, which combined indigenous traditions with influences from Persia and Byzantium. It featured multiple and single domed mosques with complex terracotta and stone ornamentation.

The most grand testament to their imperial ambitions is reflected in the ruins of the Adina Mosque, the largest mosque ever built in the Indian subcontinent.[30] The mosque has a plan similar to the Great Mosque of Damascus and elements of the pre-Islamic Sassanid Taq Kasra monument.[31][30] The Mosque City of Bagerhat is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Sultanate-mosques are scattered throughout Bangladesh and West Bengal. The style also spread to Bihar.

Literature

And with the three cups of wine, this dispute is going on.

All the poets of Hindustan have become excited

That this Persian ode to Bengal is going on.

With Persian as an official language, Bengal witnessed an influx of Persian scholars, lawyers, teachers and clerics. It was the preferred language of the aristocracy and the Sufis. Thousands of Persian books and manuscripts were published in Bengal. The earliest Persian work compiled in Bengal was a translation of Amrtakunda from Sanskrit by Qadi Ruknu’d-Din Abu Hamid Muhammad bin Muhammad al-’Amidi of Samarqand, a famous Hanafi jurist and Sufi. During the reign of Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah, the city of Sonargaon became a an important center of Persian literature, with many publications of prose and poetry. The period is described as the "golden age of Persian literature in Bengal". Its stature is illustrated by the Sultan's own correspondence with the Persian poet Hafez. When the Sultan invited Hafez to complete an incomplete ghazal by the ruler, the renowned poet responded acknowledging the grandeur of the king's court and the literary quality of Bengali-Persian poetry.[32]

In the 15th century, the Sufi poet Nur Qutb Alam pioneered Bengali Muslim poetry by establishing the Rikhta tradition, which saw poems written half in Persian and half in colloquial Bengali. The invocation tradition saw Islamic figures replacing the invocation of Hindu gods and goddesses in Bengali texts. The literary romantic tradition saw poems by Shah Muhammad Sagir on Yusuf and Zulaikha, as well as works of Bahram Khan and Sabirid Khan. The Dobhashi culture featured the use of Arabic and Persian words in Bengali texts to illustrate Muslim conquests. Epic poetry included Nabibangsha by Syed Sultan, Janganama by Abdul Hakim and Rasul Bijay by Shah Barid. Sufi literature flourished with a dominant theme of cosmology. Bengali Muslim writers produced translations of numerous Arabic and Persian works, including the Arabian Nights and the Shahnameh.[33][34]

The Sultans also patronized Bengali Hindu writers. During the reign of Alauddin Hussain Shah, Kabindra Parameshvar wrote his Pandabbijay, a Bengali adaptation of the Mahabharata. Similarly, Shrikar Nandi wrote another Bengali adaptation of the Mahabharata. Kabindra Parameshvar in his Pandabbijay eulogised Alauddin Hussain Shah.[35] Bijay Gupta wrote his Manasamangal Kāvya also during his reign. He eulogised Husain Shah by comparing him with Arjuna (samgrame Arjun Raja prabhater Rabi).[36] He mentioned him as Nrpati-Tilak (the tilak-mark of kings) and Jagat-bhusan (the adornment of the universe) as well.[37] An official of Husain Shah, Yashoraj Khan, wrote a number of Vaishnava padas and he also praised his ruler in one of his pada.[38] The Gaudiya Vaishnavism movement pioneered by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu appeared during the sultanate's era.

List of Sultans

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| Name | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah | 1352–1358 | |

| Sikandar Shah | 1358–1390 | |

| Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah | 1390–1411 | |

| Saifuddin Hamza Shah | 1411–1413 | |

| Shihabuddin Bayazid Shah | 1413–1414 | |

| Alauddin Firuz Shah I | 1414 | |

| Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah | 1414–1435 | |

| Shamsuddin Ahmad Shah | 1433–1435 | |

| Nasiruddin Mahmud Shah | 1435–1459 | |

| Rukunuddin Barbak Shah | 1459–1474 | |

| Shamsuddin Yusuf Shah | 1474–1481 | |

| Sikandar Shah II | 1481 | |

| Jalaluddin Fateh Shah | 1481–1487 | |

| Shahzada Barbak | 1487 | |

| Saifuddin Firuz Shah | 1487–1489 | |

| Mahmud Shah II | 1489–1490 | |

| Shamsuddin Muzaffar Shah | 1490–1494 | |

| Alauddin Hussain Shah | 1494–1518 | |

| Nasiruddin Nasrat Shah | 1518–1533 | |

| Alauddin Firuz Shah II | 1533 | |

| Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah | 1533–1538 | |

| Khidr Khan | 1539–1541 | |

| Qazi Fazilat | 1541–1545 | |

| Muhammad Khan Sur | 1545–1555 | |

| Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah II | 1555–1561 | |

| Ghiyasuddin Jalal Shah | 1561–1564 | |

| Ghiyasuddin Bahadur Shah III | 1564 | |

| Taj Khan Karrani | 1564–1566 | |

| Sulaiman Khan Karrani | 1566–1572 | |

| Bayazid Khan Karrani | 1572 | |

| Daud Khan Karrani | 1572–1576 |

See also

References

- ^ Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Shubhra (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis. Scarecrow Press. p. 562. ISBN 978-0-8108-8024-5.

- ^ Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Y. (19 February 2015). "A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia, 1400-1830". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- ^ Chutintharānon, Sunēt; Baker, Christopher John (1 January 2002). "Recalling Local Pasts: Autonomous History in Southeast Asia". Silkworm Books – via Google Books.

- ^ electricpulp.com. "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ Chakrabarti, Kunal; Chakrabarti, Shubhra (22 August 2013). "Historical Dictionary of the Bengalis". Scarecrow Press – via Google Books.

- ^ Bangladesh, Asiatic Society of (1 January 2003). "Banglapedia: national encyclopedia of Bangladesh". Asiatic Society of Bangladesh – via Google Books.

- ^ Lewis, David (31 October 2011). "Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Hussain, Syed Ejaz (2003). The Bengal Sultanate: Politics, Economy and Coins, A.D. 1205-1576. Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-482-3.

- ^ Richard, Arthus (2002). History of Rakhine. Boston, MD: Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-7391-0356-3. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ Yegar, Moshe (2002). Between integration and secession: The Muslim communities of the Southern Philippines, Southern Thailand, and Western Burma / Myanmar. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-7391-0356-3.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp.215-20

- ^ Samanta, Amiya K. (1 January 2000). "Gorkhaland Movement: A Study in Ethnic Separatism". APH Publishing – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Hasan, Perween (15 August 2007). "Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh". I.B.Tauris – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f electricpulp.com. "BENGAL – Encyclopaedia Iranica".

- ^ a b c d http://hudsoncress.net/hudsoncress.org/html/library/history-travel/Eaton,%20Richard%20-%20The%20Rise%20of%20Islam%20and%20the%20Bengal%20Frontier.pdf

- ^ a b Mukherjee, Rila (2011). Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism. Primus Books. p. 285. ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7.

- ^ "Jalaluddin Muhammad Shah - Banglapedia".

- ^ "Conti, Nicolo de - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ Pakistan Quarterly. 6–7: 51. 1956 https://books.google.co.nz/books?id=BTlDAQAAIAAJ&q=ralph+fitch+bangla&dq=ralph+fitch+bangla&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjtkJD4r7TMAhVIupQKHcf6AL8Q6AEIPDAG.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Portuguese, The - Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ Dunn, Ross E. (1986). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-520-05771-5.

- ^ Mukherjee, Rila (2011). Pelagic Passageways: The Northern Bay of Bengal Before Colonialism. Primus Books. pp. 305–. ISBN 978-93-80607-20-7.

- ^ "A fractured link". Dhaka Tribune. 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ Boomgaard, P. (1 January 2008). "Linking Destinies: Trade, Towns and Kin in Asian History". BRILL – via Google Books.

- ^

Nanda, J. N (2005). Bengal: the unique state. Concept Publishing Company. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-8069-149-2. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

Bengal [...] was rich in the production and export of grain, salt, fruit, liquors and wines, precious metals and ornaments besides the output of its handlooms in silk and cotton. Europe referred to Bengal as the richest country to trade with.

- ^ Israel, Milton; Wagle, Narendra K.; Studies, University of Toronto Centre for South Asian (1 December 1993). "Ethnicity, identity, migration: the South Asian context". Centre for South Asian Studies, University of Toronto – via Google Books.

- ^ "Iranians, The - Banglapedia".

- ^ Lewis, David (31 October 2011). "Bangladesh: Politics, Economy and Civil Society". Cambridge University Press – via Google Books.

- ^ "Banglapedia". En.banglapedia.org. 2015-10-25. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

hudsoncress.netwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Hasan, Perween (2007). Sultans and Mosques: The Early Muslim Architecture of Bangladesh. I.B.Tauris. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-84511-381-0.

- ^ "Persian - Banglapedia".

- ^ https://blogs.edgehill.ac.uk/sacs/files/2012/07/Document-6-Billah-A.-M.-M.-A-The-Development-of-Bengali-Literature-during-Muslim-Rule.pdf

- ^ "Sufi Literature - Banglapedia".

- ^ Sen, Sukumar (1991, reprint 2007). Bangala Sahityer Itihas, Vol.I, Template:Bn icon, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7066-966-9, pp.208-11

- ^ Sen, Sukumar (1991, reprint 2007). Bangala Sahityer Itihas, Vol.I, Template:Bn icon, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7066-966-9, p.189

- ^ Chowdhury, AM (2012). "Husain Shah". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ^ Sen, Sukumar (1991, reprint 2007). Bangala Sahityer Itihas, Vol.I, Template:Bn icon, Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7066-966-9, p.99