Albuquerque, New Mexico

| City of Albuquerque | |

| |

| Nicknames: ABQ, Burque, The 505, The Duke City, The Q | |

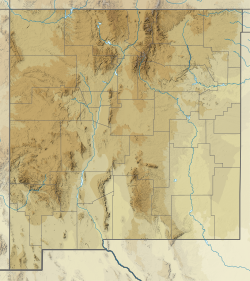

Location within Bernalillo County | |

| Coordinates: 35°06′39″N 106°36′36″W / 35.11083°N 106.61000°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Bernalillo |

| Founded | 1706 (as Alburquerque) |

| Incorporated | 1891 (as Albuquerque) |

| Named for | Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, Duke of Alburquerque |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Mayor | Tim Keller (D) |

| • City Council | Councilors |

| • State House | Representatives |

| • State Senate | State senators |

| • U.S. House | Representative |

| Area | |

| • City | 189.5 sq mi (490.9 km2) |

| • Land | 187.7 sq mi (486.2 km2) |

| • Water | 1.8 sq mi (4.7 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,312 ft (1,619.1 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 545,852 |

| • Estimate (2017)[2] | 558,545 |

| • Rank | US: 32nd |

| • Density | 2,900/sq mi (1,100/km2) |

| • Metro | 915,927 (60th) 1,171,991 (Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Las Vegas CSA) |

| • Ethnicities[3] | 69.7% White 4.6% Multiracial 4.6% American Indian 3.3% Black 2.6% Asian 46.7% Hispanic |

| Demonyms | Albuquerquean, Burqueño[4] |

| Time zone | UTC−7 (MST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−6 (MDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 87101–87125, 87131, 87151, 87153, 87154, 87158, 87174, 87176, 87181, 87184, 87185, 87187, 87190–87199 |

| Area codes | 505, 575 |

| FIPS code | 35-02000 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0928679 |

| Primary Airport | Albuquerque International Sunport ABQ (Major/International) |

| Secondary Airport | Double Eagle II Airport- KAEG (Public) |

| Website | cabq |

Albuquerque (/ˈælbəˌkɜːrki/ ⓘ AL-bə-kur-kee; Navajo: Beeʼeldííl Dahsinil [pèːʔèltíːl tɑ̀xsɪ̀nɪ̀l]; Eastern Keres: Arawageeki; Jemez: Vakêêke; Zuni: Alo:ke:k'ya; Jicarilla Apache: Gołgéeki'yé), also known locally as Duke City and abbreviated as ABQ, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico and the 32nd-most populous city in the United States, with a census-estimated population of 558,545 in 2017.[5] It is the principal city of the Albuquerque metropolitan area, which has 915,927 residents as of July 2018.[6] Albuquerque's Metropolitan statistical area is the 60th-largest in the United States. The Albuquerque MSA population includes the cities of Rio Rancho, Bernalillo, Placitas, Corrales, Los Lunas, Belen, and Bosque Farms, and forms part of the larger Albuquerque–Santa Fe–Las Vegas combined statistical area, with a total population of 1,171,991 in 2016.

The city was named in honor of Francisco Fernández de la Cueva, 10th Duke of Alburquerque, who was Viceroy of New Spain from 1702 to 1711.[7][8] The growing village was named by provincial governor Francisco Cuervo y Valdés. The Duke's title referred to the Spanish town of Alburquerque, in the province of Badajoz, near the border with Portugal.

Albuquerque serves as the county seat of Bernalillo County,[9] and is in north-central New Mexico. The Sandia Mountains run along the eastern side of Albuquerque, and the Rio Grande flows through the city. Albuquerque has one of the highest elevations of any major city in the U.S., ranging from 4,900 feet (1,490 m) above sea level near the Rio Grande to over 6,700 feet (1,950 m) in the foothill areas of Sandia Heights and Glenwood Hills.

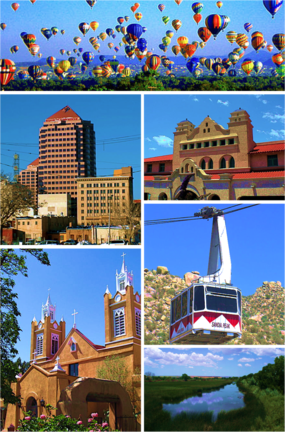

Albuquerque is home to Kirtland Air Force Base, Sandia National Laboratories, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, the University of New Mexico, Central New Mexico Community College, Presbyterian Medical Services, Presbyterian Health Services, the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Albuquerque Biological Park, the Petroglyph National Monument, and the New Mexico Technology Corridor, a concentration of high-tech private companies and government institutions. Albuquerque is also the home of the International Balloon Fiesta, the world's largest gathering of hot-air balloons, taking place every October.[10]

Etymology

The name of the city has its origin through Latin, deriving from albus quercus meaning "white oak". The name was probably given in reference to the prevalence of cork oaks in the province of Badajoz, which have white wood when the bark is removed.

The first "r" in Alburquerque was later dropped, probably due to association with the prominent Portuguese general Alfonso de Albuquerque, whose family title (among others) and then name originated from the town of Alburquerque in Spain, which was once a dominion of the kings of Portugal and used the Portuguese variant spelling of its name. The change was also in part because newer Anglo citizens found the original name difficult to pronounce.

History

Petroglyphs carved into basalt in the western part of the city bear testimony to an early Native American presence in the area, now preserved in the Petroglyph National Monument.

The Tanoan and Keresan peoples had lived along the Rio Grande for centuries before European settlers arrived in what is now Albuquerque. By the 1500s, there were around 20 Tiwa pueblos along a 60-mile (97 km) stretch of river from present-day Algodones to the Rio Puerco confluence south of Belen. Of these, 12 or 13 were densely clustered near present-day Bernalillo and the remainder were spread out to the south.[11]

Two Tiwa pueblos lie specifically on the outskirts of the present-day city, both of which have been continuously inhabited for many centuries: Sandia Pueblo, which was founded in the 14th century,[12] and the Pueblo of Isleta, for which written records go back to the early 17th century, when it was chosen as the site of the San Agustín de la Isleta Mission, a Catholic mission.

The Navajo, Apache, and Comanche peoples were also likely to have set camps in the Albuquerque area, as there is evidence of trade and cultural exchange between the different Native American groups going back centuries before European conquest.[13]

Albuquerque was founded in 1706 as the Spanish colonial outpost of Villa de Alburquerque.[14] Albuquerque was a farming community and strategically located military outpost along the Camino Real. The town was also the sheep-herding center of the West.[15] Spain established a presidio in Albuquerque in 1706.

After 1821, Mexico also had a military presence there. The town of Alburquerque was built in the traditional Spanish village pattern: a central plaza surrounded by government buildings, homes, and a church. This central plaza area has been preserved and is open to the public as a museum, cultural area, and center of commerce. It is referred to as "Old Town Albuquerque" or simply "Old Town". Historically it was sometimes referred to as "La Placita" (Little Plaza in Spanish). On the north side of Old Town Plaza is San Felipe de Neri Church. Built in 1793, it is one of the oldest surviving buildings in the city.[16]

After the American occupation of New Mexico, Albuquerque had a federal garrison and quartermaster depot, the Post of Albuquerque, from 1846 to 1867. During the Civil War, Albuquerque was occupied in February 1862 by Confederate troops under General Henry Hopkins Sibley, who soon afterward advanced with his main body into northern New Mexico. During his retreat from Union troops into Texas he made a stand on April 8, 1862, at Albuquerque and fought the Battle of Albuquerque against a detachment of Union soldiers commanded by Colonel Edward R. S. Canby. This daylong engagement at long range led to few casualties.

When the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad arrived in 1880, it bypassed the Plaza, locating the passenger depot and railyards about 2 miles (3 km) east in what quickly became known as New Albuquerque or New Town. The railway company built a hospital for its workers that was later a juvenile psychiatric facility and has now been converted to a hotel.[17] Many Anglo merchants, mountain men, and settlers slowly filtered into Albuquerque creating a major mercantile commercial center which is now Downtown Albuquerque. Due to a rising rate of violent crime, gunman Milt Yarberry was appointed the town's first marshal that year. New Albuquerque was incorporated as a town in 1885, with Henry N. Jaffa its first mayor. It was incorporated as a city in 1891.[18]: 232–233 Old Town remained a separate community until the 1920s when it was absorbed by Albuquerque. Old Albuquerque High School, the city's first public high school, was established in 1879. Congregation Albert, a Reform synagogue established in 1897, is the oldest continuing Jewish organization in the city.[19]

By 1900, Albuquerque boasted a population of 8,000 inhabitants and all the modern amenities, including an electric street railway connecting Old Town, New Town, and the recently established University of New Mexico campus on the East Mesa. In 1902, the famous Alvarado Hotel was built adjacent to the new passenger depot, and it remained a symbol of the city until it was razed in 1970 to make room for a parking lot. In 2002, the Alvarado Transportation Center was built on the site in a manner resembling the old landmark. The large metro station functions as the downtown headquarters for the city's transit department. It also serves as an intermodal hub for local buses, Greyhound buses, Amtrak passenger trains, and the Rail Runner commuter rail line.

New Mexico's dry climate brought many tuberculosis patients to the city in search of a cure during the early 20th century, and several sanitaria sprang up on the West Mesa to serve them. Presbyterian Hospital and St. Joseph Hospital, two of the largest hospitals in the Southwest, had their beginnings during this period. Influential New Deal–era governor Clyde Tingley and famed Southwestern architect John Gaw Meem were among those brought to New Mexico by tuberculosis.

The first travelers on Route 66 appeared in Albuquerque in 1926, and before long, dozens of motels, restaurants, and gift shops had sprung up along the roadside to serve them. Route 66 originally ran through the city on a north–south alignment along Fourth Street, but in 1937 it was realigned along Central Avenue, a more direct east–west route. The intersection of Fourth and Central downtown was the principal crossroads of the city for decades. The majority of the surviving structures from the Route 66 era are on Central, though there are also some on Fourth. Signs between Bernalillo and Los Lunas along the old route now have brown, historical highway markers denoting it as Pre-1937 Route 66.

The establishment of Kirtland Air Force Base in 1939, Sandia Base in the early 1940s, and Sandia National Laboratories in 1949, would make Albuquerque a key player of the Atomic Age. Meanwhile, the city continued to expand outward into the Northeast Heights, reaching a population of 201,189 by 1960. In 1990, it was 384,736 and in 2007 it was 518,271. In June 2007, Albuquerque was listed as the sixth fastest-growing city in the United States.[20] In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau reported Albuquerque's population as 34.5% Hispanic and 58.3% non-Hispanic white.[21]

Albuquerque's downtown entered the same phase and development (decline, "urban renewal" with continued decline, and gentrification) as nearly every city across the United States. As Albuquerque spread outward, the downtown area fell into a decline. Many historic buildings were razed in the 1960s and 1970s to make way for new plazas, high-rises, and parking lots as part of the city's urban renewal phase. As of 2010[update], only recently has Downtown Albuquerque come to regain much of its urban character, mainly through the construction of many new loft apartment buildings and the renovation of historic structures such as the KiMo Theater, in the gentrification phase.

During the 21st century, the Albuquerque population has continued to grow rapidly. The population of the city proper was estimated at 528,497 in 2009, up from 448,607 in the 2000 census.[22] During 2005 and 2006, the city celebrated its tricentennial with a diverse program of cultural events.

The passage of the Planned Growth Strategy in 2002–2004 was the community's strongest effort to create a framework for a more balanced and sustainable approach to urban growth.[23]

Urban sprawl is limited on three sides—by the Sandia Pueblo to the north, the Isleta Pueblo and Kirtland Air Force Base to the south, and the Sandia Mountains to the east. Suburban growth continues at a strong pace to the west, beyond the Petroglyph National Monument, once thought to be a natural boundary to sprawl development.[24]

Because of less-costly land and lower taxes, much of the growth in the metropolitan area is taking place outside of the city of Albuquerque itself. In Rio Rancho to the northwest, the communities east of the mountains, and the incorporated parts of Valencia County, population growth rates approach twice that of Albuquerque. The primary cities in Valencia County are Los Lunas and Belen, both of which are home to growing industrial complexes and new residential subdivisions. The mountain towns of Tijeras, Edgewood, and Moriarty, while close enough to Albuquerque to be considered suburbs, have experienced much less growth compared to Rio Rancho, Bernalillo, Los Lunas, and Belen. Limited water supply and rugged terrain are the main limiting factors for development in these towns. The Mid Region Council of Governments (MRCOG), which includes constituents from throughout the Albuquerque area, was formed to ensure that these governments along the middle Rio Grande would be able to meet the needs of their rapidly rising populations. MRCOG's cornerstone project is currently the New Mexico Rail Runner Express. In October 2013, the Albuquerque Journal reported Albuquerque as the third best city to own an investment property.[25]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, Albuquerque has a total area of 189.5 square miles (490.9 km2), of which 187.7 square miles (486.2 km2) is land and 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2), or 0.96%, is water.[26]

Albuquerque lies within the northern, upper portion of the Chihuahuan Desert ecoregion, based on landforms including drainage patterns, climate, and floral and faunal associations.[27][28] Located in central New Mexico, the city also has noticeable influences from the adjacent Colorado Plateau semi-desert, Arizona-New Mexico Mountains, and Southwest plateaus and plains steppe ecoregions, depending on where one is located. Its main geographic connection lies with southern New Mexico, while culturally, Albuquerque is a crossroads of most of New Mexico.

Landforms and Drainage

Albuquerque has one of the highest elevations of any major city in the United States, though the effects of this are greatly tempered by its southwesterly continental position. The elevation of the city ranges from 4,900 feet (1,490 m) above sea level near the Rio Grande (in the Valley) to over 6,700 feet (1,950 m) in the foothill areas of Sandia Heights and Glenwood Hills. At the airport, the elevation is 5,352 feet (1,631 m) above sea level.

The Rio Grande is classified, like the Nile, as an "exotic" river because it flows through a desert. The New Mexico portion of the Rio Grande lies within the Rio Grande Rift Valley, bordered by a system of faults, including those that lifted up the adjacent Sandia and Manzano Mountains, while lowering the area where the life-sustaining Rio Grande now flows.

Geology

Albuquerque lies in the Albuquerque Basin, a portion of the Rio Grande rift.[29] The Sandia Mountains are the predominant geographic feature visible in Albuquerque. "Sandía" is Spanish for "watermelon", and is popularly believed to be a reference to the brilliant coloration of the mountains at sunset: bright pink (melon meat) and green (melon rind). The pink is due to large exposures of granodiorite cliffs, and the green is due to large swaths of conifer forests. However, Robert Julyan notes in The Place Names of New Mexico, "the most likely explanation is the one believed by the Sandia Pueblo Indians: the Spaniards, when they encountered the Pueblo in 1540, called it Sandia, because they thought the squash growing there were watermelons, and the name Sandia soon was transferred to the mountains east of the pueblo."[30] He also notes that the Sandia Pueblo Indians call the mountain Bien Mur, "big mountain."[30]

The Sandia foothills, on the west side of the mountains, have soils derived from that same rock material with varying sizes of decomposed granite, mixed with areas of clay and caliche (a calcium carbonate deposit common in the arid southwestern USA), along with some exposed granite bedrock.

Below the foothills, the area usually called the "Northeast Heights" consists of a mix of clay and caliche soils, overlaying a layer of decomposed granite, resulting from long-term outwash of that material from the adjacent mountains. This bajada is quite noticeable when driving into Albuquerque from the north or south, due to its fairly uniform slope from the mountains' edge downhill to the valley. Sand hills are scattered along the I-25 corridor and directly above the Rio Grande Valley, forming the lower end of the Heights.

The Rio Grande Valley, due to long-term shifting of the actual river channel, contains layers and areas of soils varying between caliche, clay, loam, and even some sand. It is the only part of Albuquerque where the water table often lies close to the surface, sometimes less than 10 feet (3.0 m).

The last significant area of Albuquerque geologically is the West Mesa: this is the elevated land west of the Rio Grande, including "West Bluff", the sandy terrace immediately west and above the river, and the rather sharply defined volcanic escarpment above and west of most of the developed city. The west mesa commonly has soils often referred to as "blow sand", along with occasional clay and caliche and even basalt, nearing the escarpment.

Potential and Former Native Flora

Flora or vegetation surrounding the built portions of the city are typical of their desert southwestern and interior west setting, within the varied elevations and terrain. The limits are by significant urbanization, including much infill development occuring mostly in the last 15 years.

The western half of Albuquerque, with mostly sandy soils, includes Chihuahuan Desert sand scrub and mesa vegetation such as sand sagebrush (Artemisia filifolia), fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens). Some similar grass and seasonal wildflower species occur that also occur in areas east of the Rio Grande, but in much lower densities. Sparsely as well, sandy soil grasses occur such as indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus), and mesa dropseed (Sporobolus flexuosus). Arroyos contain desert willow (Chilopsis linearis) while breaks and the prominent volcanic escarpment include threeleaf sumac with less frequent stands of oneseed juniper (Juniperus monosperma), netleaf hackberry (Celtis reticulata), and isolated littleleaf sumac (Rhus microphylla).

Eastern areas of Albuquerque have more fine clay and caliche soils, plus more rainfall and slightly cooler temperatures, so natural vegetation is dominated by Chihuahuan desert grassland species such as fluffgrass (Erioneuron pulchellum), purple threeawn (Hilaria mutica or Pleuraphis mutica), bush muhly (Muhlenbergia porteri), and black grama (Bouteloua eriopoda). Some woody plants occur in overall grassy areas, mainly fourwing saltbush (Atriplex canescens) and snakeweed (Gutierrezia microcephala). Isolated stands of creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) were reported by long-time residents on gravelly, desert pavement soils existing above arroyos and warm breaks, prior to urbanization in the Northeast Quadrant of Albuiquerque. Today only remnants of creosote bush scrub remain, in the lower foothills where granitic soils are less of a deterrant than to creosote bush, including feather dalea (Dalea formosa), mariola (Parthenium incanum), and beebrush or oreganillo (Aloysia wrightii).

Soaptree (Yucca elata) and broom dalea (Psorothamnus scoparius), primarily indicative of sandy soils in the northern Chihuahuan Desert, are currently found or were once existing on sand hills and breaks on both sides of the Rio Grande Valley, roughly where the Petroglyph Escarpment, and today's Coors Road and Interstate 25 are located.

The Rio Grande Valley proper bisects Albuquerque, and it has been urbanized the longest of all areas of the city. Some botanists and longtime residents recall riparian vegetation present that is typical of southern New Mexico and the Chihuahuan Desert, including screwbean mesquite or tornillo (Prosopis pubescens), Gooding's willow (Salix goodingii), and siant sacaton (Sporobulus wrightii). The present bosque or gallery forest of Rio Grande cottonwood (Populus deltoides var. wislizeni) and coyote willow (Salix exigua) is theorized to have been more savannah-like, prior to replanting in the 1930's. Grass and low cactus cover of many areas is typical of a broader region of the intermountain west riparian zones, such as saltgrass (Distychilis spp.) and alkali sacaton (Sporobulus airoides). Discontinuous, small stands of desert olive or New Mexico olive (Forestiera pubescens var. neomexicana), Arizona walnut (Juglans major), and Arizona ash (Fraxinus velutina) can be seen near bosque areas and near former river bends in central New Mexico just north and south of the Albuquerque city limits. The vast majority of Albuquerque's valley is now covered in invasive, non-native species including mostly Siberian elm, Russian olive, and saltcedar, though some restoration to native species is occuring, similar to the limited species used in the 1930's of Populus and Salix.

Albuquerque's western Sandia foothills receive about 50 percent more precipitation than most of the city, and with granitic, coarse soils and rock outcrops and boulders dominant, they have a greater and different diversity of flora in the form of savanna and chaparral, dominated by lower and middle zones of Arizona-New Mexico Mountains vegetation, with a slight orientation towards the Chihuahuan Desert. Dominant plants include shrub or desert live oak (Querus turbinella), gray oak (Quercus grisea), hairy mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus breviflorus), oneseed juniper (Juniperus monosperma), Colorado piñon (Pinus edulis), threeleaf sumac (Rhus trilobata), Engelmann prickly pear (Opuntia engelmannii), juniper prickly pear (Opuntia hystricina var. juniperiana), and Beargrass (Nolina greenei, formerly considered Nolina texana). Similar grasses occur that are native to the eastern half of the city, but often of a higher density owing to increased precipitation. The foothills of Albuquerque are much less urbanized, the vegetation altered or removed than anywhere else in the city, though the lower areas have been mostly developed in a more dense suburban pattern in mostly developed communities including North Albuquerque Acres, Tanoan, High Desert, Glenwood Hills, Embudo Hills, Supper Rock, and Four Hills.

Native and other fauna

Iconic, larger birds seen often in Albuquerque and central New Mexico include the greater roadrunner, common and Chihuahuan raven, common and great-tailed grackle, and American crow. Smaller but even more common birds in Albuquerque include Gambel's and scaled quail, several species of hummingbirds, house finch, white wing and mourning dove, Inca dove, cactus wren, curvebilled thrasher, and pinyon jay. Valley areas host sandhill cranes each winter, as well as numerous riparian zone-favoring species duie to the presence of disturbed ground and riparian moisture availability. Foothill areas add to other areas with the occasional phainopepla but often the mountain blue bird in the spring and fall, plus Cooper's, Swainson's, and red tail hawk, Scott's oriole, and in winter chipping sparrow in the narrow bands of live oaks lining spring-fed arroyos.

Reptiles and snakes are numerous mostly in outlying areas of the west mesa and foothills, where their optimal habitat is still intact. The exception are some smaller lizards, which are seen in more urbanized and suburban areas, as well. Non-venomous species include garter snake, king snake, and the beneficial but large bullsnake. Venomous species include numerous western diamondback rattlesnake, plus prairie rattler, banded rock rattlesnake, and sidewinder. The large leopard lizard can be found in rocky ground especially in the foothills, though numerous, smaller lizards are found there and lower in the city.

Other common fauna include coyote, several species of squirrels, bobcat, and rarely in the boulder fields of the foothills, ringtail cat. There are occasional, existing colonies of Gunnison's prairie dog mostly in foothill and far western upland desert grassland areas. Javelina have been reported and even documented via wildlife camera in wooded spots near springs and stock tanks located just south of the city on the easternmost portions of Kirtland Air Force Base below the Manzanita Mountains, as well as the higher but woodland areas of the east mountain areas, north and south of Interstate 40, and near the valley in Valencia County 30 miles south of Albuquerque. Larger fauna including black bear, mountain lion, and mule and white-tail deer are found in the foothills.

Insects are typical of arid, interior western locales of the United States with many Chihuahuan Desert species. Those include several species of daytime and nocturnal cicada in the early summer, vinegaroon or whip scorpion, centipede, mildly-venomous house centipede, and the venomous bark scorpion. Africanized bees have colonized areas and been documented by extermination services and agricultural interests in outlying areas for over one decade, though they are not commonplace. Most common are several species of cricket, miller moth, sphinx moth, and other insects common to the dry, interior west occur. Insects like other fauna in the southwest, tend to be most common where moisture can concentrate or last for more time after infrequent storm events.

Cityscape

Quadrants

Albuquerque is geographically divided into four quadrants which are officially part of the mailing address. They are NE (northeast), NW (northwest), SE (southeast), and SW (southwest). The north-south dividing line is Central Avenue (the path that Route 66 took through the city) and the east-west dividing line is the Rail Runner tracks.

Northeast Quadrant

This quadrant has been experiencing a housing expansion since the late 1950s. It abuts the base of the Sandia Mountains and contains portions of the foothills neighborhoods, which are significantly higher, in elevation and price range, than the rest of the city. Running from Central Avenue and the railroad tracks to the Sandia Peak Aerial Tram, this is the largest quadrant both geographically and by population. The University of New Mexico, the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Nob Hill, the Uptown area which includes three shopping malls (Coronado Center, ABQ Uptown, and Winrock Town Center), Hoffmantown, Journal Center, Cliff's Amusement Park, and Balloon Fiesta Park are all located in this quadrant.

Some of the most affluent neighborhoods in the city are located here, including: High Desert, Tanoan, Sandia Heights, and North Albuquerque Acres. Parts of Sandia Heights and North Albuquerque Acres are outside the city limits proper. A few houses in the farthest reach of this quadrant lie in the Cibola National Forest, just over the line into Sandoval County.

Northwest Quadrant

This quadrant contains historic Old Town Albuquerque, which dates back to the 18th century, as well as the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. The area has a mixture of commercial districts and low to high-income neighborhoods. Northwest Albuquerque includes the largest section of Downtown, Rio Grande Nature Center State Park and the Bosque ("woodlands"), Petroglyph National Monument, Double Eagle II Airport, Martineztown, the Paradise Hills neighborhood, Taylor Ranch, and Cottonwood Mall.

Additionally, the North Valley settlement, outside the city limits, which has some expensive homes and small ranches along the Rio Grande, is located here. The city of Albuquerque engulfs the village of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque. A small portion of the rapidly developing area on the west side of the river south of the Petroglyphs, known as the "West Mesa" or "Westside", consisting primarily of traditional residential subdivisions, also extends into this quadrant. The city proper is bordered on the north by the North Valley, the village of Corrales, and the city of Rio Rancho.

Southeast Quadrant

Kirtland Air Force Base, Sandia National Laboratories, Sandia Science & Technology Park, Albuquerque International Sunport, Eclipse Aerospace, American Society of Radiologic Technologists, Central New Mexico Community College, Albuquerque Veloport, University Stadium, Isotopes Park, The Pit, Mesa del Sol, The Pavilion, Albuquerque Studios, Isleta Resort & Casino, the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History, New Mexico Veterans' Memorial, and Talin Market are all located in the Southeast quadrant.

The upscale neighborhood of Four Hills is located in the foothills of Southeast Albuquerque. Other neighborhoods include Nob Hill, Ridgecrest, Willow Wood, and Volterra.

Southwest Quadrant

Traditionally consisting of agricultural and rural areas and suburban neighborhoods, the Southwest quadrant comprises the south-end of Downtown Albuquerque, the Barelas neighborhood, the rapidly-growing west side, and the community of South Valley, New Mexico, often referred to as "The South Valley". Although the city limits of Albuquerque do not include the South Valley, the quadrant extends through it all the way to the Isleta Indian Reservation. Newer suburban subdivisions on the West Mesa near the southwestern city limits join homes of older construction, some dating back as far as the 1940s. This quadrant includes the old communities of Atrisco, Los Padillas, Huning Castle, Kinney, Westgate, Westside, Alamosa, Mountainview, and Pajarito. The Bosque ("woodlands"), the National Hispanic Cultural Center, the Rio Grande Zoo, and Tingley Beach are also located here.

A new adopted development plan, the Santolina Master Plan, will extend development on the west side past 118th Street SW to the edge of the Rio Puerco Valley, and house 100,000 by 2050. It is unclear at this time whether the Santolina development will be annexed into the City of Albuquerque or incorporated into its own city when its development does occur.[31]

Climate

Albuquerque has a warm-temperate climate [1], characterized as arid or the driest end of semi-arid depending on the criteria used. Along with truly semi-arid Lubbock, Texas, it has been misclassified as a Cold semi-arid climate (BSk in the Köppen climate classification) by that particlular system. Albuquerque is in the northern tip of the Chihuahuan Desert, bordering the Colorado Plateau and Arizona-Mountains ecoregions, and sperated by those mountains from the central great plains highlands and southern great plains.[27][28] The average annual precipitation is less than half of evaporation, and no month's daily temperature averages below freezing.

Albuquerque's climate is usually sunny and dry, with an average of 3,415 sunshine hours per year.[32][33] Brilliant sunshine defines the region, averaging 278 days a year; periods of variably mid and high-level cloudiness temper the sun at other times. Extended cloudiness is rare.

Winter consists of cool days and cold nights. December, the coolest month, averages 36.3 °F (2.4 °C), although low temperatures bottom out in early January, and the coolest temperature of the year is typically around 10 °F (−12 °C).[34] Most low temperatures in December, January, and February are below freezing, even if just between midnight and 8 am.

Spring is windy, sometimes unsettled with some rain, though spring is usually the driest part of the year in Albuquerque. March and April tend to see many days with the wind blowing at 20 to 30 mph (32 to 48 km/h), and afternoon gusts can produce periods of blowing sand and dust. In May, the winds tend to subside.

Summer is relatively tolerable for most because of low humidity, except for some days during the North American Monsoon. There are 2.7 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs annually, mostly in June and July and rarely in August due in part to the monsoon; an average 60 days see 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs.

Fall sees less rain than summer, though the weather can be more unsettled closer to winter.

Precipitation averages just under 9.5 inches per year using recent 30 year periods, more realistically characterized as about 8.5 inches per year using the period-of-record from 100 years of NOAA climatology. On average, January is the driest month, while July and August are the wettest months, as a result of shower and thunderstorm activity produced by the North American Monsoon prevalent over the Southwestern United States.

Albuquerque averages around 9 inches of snow per winter, and experiences several accumulating snow events each season. Locations in the Northeast Heights and Eastern Foothills tend to receive more snowfall due to each region's higher elevation and proximity to the mountains. The city was one of several in the region experiencing a severe winter storm on December 28–30, 2006, with locations in Albuquerque receiving between 10.5 and 26 inches (27 and 66 cm) of snow.[35] More recently, a major winter storm in late February 2015 dropped up to a foot (30 cm) of snow on most of the city.

The mountains and highlands east of the city create a rain shadow effect, due to the drying of air descending the mountains; the city usually receives very little rain or snow, averaging 8–9 inches (216 mm) of precipitation per year. Valley and west mesa areas, farther from the mountains are drier, averaging 6–8 inches of annual precipitation; the Sandia foothills tend to lift any available moisture, enhancing precipitation to about 10–17 inches annually.

Traveling west, north, and east of Albuquerque, one quickly rises in elevation and leaves the sheltering effect of the valley to enter a noticeably cooler and slightly wetter environment. One such area is still considered part of metro Albuquerque, commonly called the East Mountain area; it is covered in savannas or woodlands of low juniper and piñon trees, reminiscent of the lower parts of the southern Rocky Mountains, which do not actually contact Albuquerque proper. Most rain occurs during the late summer monsoon season, typically starting in early July and ending in mid-September.

| Climate data for Albuquerque (Albuquerque International Sunport), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1891–present[a] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

79 (26) |

85 (29) |

89 (32) |

98 (37) |

107 (42) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

100 (38) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

72 (22) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 60.1 (15.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

76.1 (24.5) |

83.2 (28.4) |

91.1 (32.8) |

98.8 (37.1) |

99.4 (37.4) |

95.7 (35.4) |

91.3 (32.9) |

82.5 (28.1) |

70.8 (21.6) |

60.3 (15.7) |

100.2 (37.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 46.8 (8.2) |

52.5 (11.4) |

60.5 (15.8) |

69.0 (20.6) |

78.8 (26.0) |

88.3 (31.3) |

90.1 (32.3) |

87.2 (30.7) |

80.7 (27.1) |

69.0 (20.6) |

55.8 (13.2) |

46.1 (7.8) |

68.8 (20.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.4 (2.4) |

41.4 (5.2) |

48.1 (8.9) |

56.0 (13.3) |

65.6 (18.7) |

74.9 (23.8) |

78.3 (25.7) |

76.2 (24.6) |

69.3 (20.7) |

57.5 (14.2) |

44.9 (7.2) |

36.3 (2.4) |

57.2 (14.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.1 (−3.3) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

35.7 (2.1) |

43.0 (6.1) |

52.5 (11.4) |

61.6 (16.4) |

66.4 (19.1) |

65.1 (18.4) |

57.9 (14.4) |

46.1 (7.8) |

34.1 (1.2) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

45.5 (7.5) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 14.1 (−9.9) |

16.7 (−8.5) |

22.3 (−5.4) |

29.4 (−1.4) |

39.0 (3.9) |

50.3 (10.2) |

59.4 (15.2) |

57.6 (14.2) |

46.3 (7.9) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

9.6 (−12.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −17 (−27) |

−10 (−23) |

6 (−14) |

13 (−11) |

25 (−4) |

35 (2) |

42 (6) |

46 (8) |

26 (−3) |

19 (−7) |

−7 (−22) |

−16 (−27) |

−17 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.38 (9.7) |

0.48 (12) |

0.57 (14) |

0.61 (15) |

0.50 (13) |

0.66 (17) |

1.50 (38) |

1.58 (40) |

1.08 (27) |

1.02 (26) |

0.57 (14) |

0.50 (13) |

9.45 (240) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.1 (5.3) |

1.8 (4.6) |

1.1 (2.8) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

1.0 (2.5) |

2.7 (6.9) |

9.6 (24) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 4.1 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 3.2 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 61.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.4 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 9.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 56.3 | 49.8 | 39.7 | 32.5 | 31.1 | 29.8 | 41.9 | 47.1 | 47.4 | 45.3 | 49.9 | 56.8 | 44.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 234.2 | 225.3 | 270.2 | 304.6 | 347.4 | 359.3 | 335.0 | 314.2 | 286.7 | 281.4 | 233.8 | 223.3 | 3,415.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 75 | 74 | 73 | 78 | 80 | 83 | 76 | 75 | 77 | 80 | 75 | 73 | 77 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[36][37][32] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Albuquerque South Valley (elevation 4,955 ft (1,510.3 m), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1991–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 73 (23) |

79 (26) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

101 (38) |

105 (41) |

103 (39) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

89 (32) |

76 (24) |

70 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 50.3 (10.2) |

56.2 (13.4) |

63.4 (17.4) |

71.7 (22.1) |

80.1 (26.7) |

89.3 (31.8) |

91.4 (33.0) |

89.1 (31.7) |

82.4 (28.0) |

71.3 (21.8) |

59.0 (15.0) |

49.3 (9.6) |

71.2 (21.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.6 (2.0) |

40.9 (4.9) |

47.6 (8.7) |

55.4 (13.0) |

63.8 (17.7) |

72.3 (22.4) |

76.7 (24.8) |

75.3 (24.1) |

67.8 (19.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

43.7 (6.5) |

35.5 (1.9) |

55.9 (13.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.9 (−6.2) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

39.0 (3.9) |

47.5 (8.6) |

55.3 (12.9) |

62.0 (16.7) |

61.5 (16.4) |

53.1 (11.7) |

40.4 (4.7) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

40.7 (4.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −4 (−20) |

−5 (−21) |

6 (−14) |

22 (−6) |

26 (−3) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

19 (−7) |

9 (−13) |

2 (−17) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.46 (12) |

0.53 (13) |

0.67 (17) |

0.62 (16) |

0.54 (14) |

0.58 (15) |

1.44 (37) |

1.72 (44) |

1.25 (32) |

1.13 (29) |

0.64 (16) |

0.63 (16) |

10.21 (259) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.7 (4.3) |

0.7 (1.8) |

0.9 (2.3) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.5 (1.3) |

2.8 (7.1) |

7.2 (18) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 8.9 | 5.3 | 4.9 | 3.0 | 3.9 | 57.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1.3 | 4.5 |

| Source: NOAA[38] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Albuquerque Foothills (elevation 6,120 ft (1,865.4 m), 1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 46.0 (7.8) |

51.5 (10.8) |

59.6 (15.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

78.6 (25.9) |

87.8 (31.0) |

89.4 (31.9) |

86.5 (30.3) |

79.7 (26.5) |

67.3 (19.6) |

54.4 (12.4) |

44.8 (7.1) |

68.0 (20.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 36.4 (2.4) |

40.7 (4.8) |

47.1 (8.4) |

54.9 (12.7) |

64.0 (17.8) |

73.1 (22.8) |

75.8 (24.3) |

73.5 (23.1) |

67.1 (19.5) |

55.5 (13.1) |

43.7 (6.5) |

35.6 (2.0) |

55.7 (13.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 26.7 (−2.9) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

34.6 (1.4) |

41.0 (5.0) |

49.5 (9.7) |

58.3 (14.6) |

62.2 (16.8) |

60.6 (15.9) |

54.5 (12.5) |

43.6 (6.4) |

33.1 (0.6) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

43.4 (6.3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.76 (19) |

0.82 (21) |

1.36 (35) |

1.03 (26) |

0.82 (21) |

0.71 (18) |

2.25 (57) |

2.97 (75) |

1.54 (39) |

1.54 (39) |

1.29 (33) |

1.21 (31) |

16.30 (414) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.7 (12) |

3.9 (9.9) |

5.0 (13) |

2.0 (5.1) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.6 (1.5) |

3.0 (7.6) |

7.3 (19) |

26.5 (67) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.6 | 6.0 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 11.8 | 10.7 | 7.5 | 6.5 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 80.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.9 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 4.3 | 18.2 |

| Source: NOAA[39] | |||||||||||||

Hydrology

Albuquerque's drinking water comes from a combination of Rio Grande water (river water diverted from the Colorado River basin through the San Juan-Chama Project[40]) and a delicate aquifer that has been described as an "underground Lake Superior". The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority (ABCWUA) has developed a water resources management strategy that pursues conservation and the direct extraction of water from the Rio Grande for the development of a stable underground aquifer in the future.[41][42]

The aquifer of the Rio Puerco is too saline to be cost-effectively used for drinking. Much of the rainwater Albuquerque receives does not recharge its aquifer. It is diverted through a network of paved channels and arroyos and empties into the Rio Grande.

Of the 62,780 acre-feet (77,440,000 m3) per year of the water in the upper Colorado River basin entitled to municipalities in New Mexico by the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, Albuquerque owns 48,200. The water is delivered to the Rio Grande by the San Juan–Chama Project. The project's construction was initiated by legislation signed by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, and was completed in 1971. This diversion project transports water under the continental divide from Navajo Lake to Lake Heron on the Rio Chama, a tributary of the Rio Grande. In the past much of this water was resold to downstream owners in Texas. These arrangements ended in 2008 with the completion of the ABCWUA's Drinking Water Supply Project.[43]

The ABCWUA's Drinking Water Supply Project uses a system of adjustable-height dams to skim water from the Rio Grande into sluices that lead to water treatment facilities for direct conversion to potable water. Some water is allowed to flow through central Albuquerque, mostly to protect the endangered Rio Grande Silvery Minnow. Treated effluent water is recycled into the Rio Grande south of the city. The ABCWUA expects river water to comprise up to seventy percent of its water budget in 2060. Groundwater will constitute the remainder. One of the policies of the ABCWUA's strategy is the acquisition of additional river water.[42][44] : Policy G, 14

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 2,315 | — | |

| 1890 | 3,785 | 63.5% | |

| 1900 | 6,238 | 64.8% | |

| 1910 | 11,020 | 76.7% | |

| 1920 | 15,157 | 37.5% | |

| 1930 | 26,570 | 75.3% | |

| 1940 | 35,449 | 33.4% | |

| 1950 | 96,815 | 173.1% | |

| 1960 | 201,189 | 107.8% | |

| 1970 | 244,501 | 21.5% | |

| 1980 | 332,920 | 36.2% | |

| 1990 | 384,736 | 15.6% | |

| 2000 | 448,607 | 16.6% | |

| 2010 | 545,852 | 21.7% | |

| 2017 (est.) | 558,545 | [45] | 2.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[46] | |||

| Demographic profile | 2010[47] | 1990[21] | 1970[21] | 1950[21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 69.7% | 78.2% | 95.7% | 98.0% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 42.1% | 58.3% | 63.3% | N/A |

| Black or African American | 3.3% | 3.0% | 2.2% | 1.3% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 46.7% | 34.5% | 33.1% | N/A |

| Asian | 2.6% | 1.7% | 0.3% | 0.1% |

As of the United States census of 2010, there were 545,852 people, 239,166 households, and 224,330 families residing in the city.[48] The population density was 3010.7/mi² (1162.6/km²). There were 239,166 housing units at an average density of 1,556.7 per square mile (538.2/km²).

The racial makeup of the city was 69.7% White (Non-Hispanic white 42.1%), 4.6% Native American, 3.3% Black or African American, 2.6% Asian, 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and 4.6% Multiracial (two or more races).[49][50]

The ethnic makeup of the city was 46.7% of the population being Hispanics or Latinos of any race.[49]

There were 239,116 households out of which 33.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 12.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.5% were non-families. 30.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.02.

The age distribution was 24.5% under 18, 10.6% from 18 to 24, 30.9% from 25 to 44, 21.9% from 45 to 64, and 12.0% who were 65 or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 91.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $38,272, and the median income for a family was $46,979. Males had a median income of $34,208 versus $26,397 for females. The per capita income for the city was $20,884. About 10.0% of families and 13.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 17.4% of those under age 18 and 8.5% of those age 65 or over.

Religion

According to a study by Sperling's BestPlaces, the majority of the religious population in Albuquerque are Christian.[51]

Being a historical Spanish and Mexican city, the Catholic Church is the largest Christian church in Albuquerque. The Catholic population of Albuquerque is served by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Santa Fe, whose administrative center is located in the city. Collectively, other Christian churches and organizations such as the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, and others make up the second largest group in the city. Baptists form the third largest Christian group, followed by the Latter Day Saints, Pentecostals, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans and Episcopalians.

The second largest religious population in the city are eastern religions such as Buddhism, Sikhism, and Hinduism.[51] The Albuquerque Sikh Gurudwara and Guru Nanak Gurdwara Albuquerque serve the city's Sikh populace; the Hindu Temple Society of New Mexico serves the Hindu population; several Buddhist temples and centers are located in the city limits.

Judaism is the second-largest non-Christian religious group in Albuquerque, followed by Islam.[51] Congregation Albert is a Reform synagogue established in 1897.[19] It is the oldest continuing Jewish organization in the city.

Arts and culture

One of the major art events in the state is the summertime New Mexico Arts and Crafts Fair, a nonprofit show exclusively for New Mexico artists and held annually in Albuquerque since 1961.[52][53] Albuquerque is home to over 300 other visual arts, music, dance, literary, film, ethnic, and craft organizations, museums, festivals and associations.

Points of interest

Local museums, galleries, shops and other points of interest include the Albuquerque Biological Park, Albuquerque Museum, New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, and Old Town Albuquerque. Albuquerque's live music/performance venues include Isleta Amphitheater, Tingley Coliseum, Sunshine Theater and the KiMo Theater.

Local cuisine prominently features green chile, which is widely available in restaurants, including national fast-food chains. Albuquerque has an active restaurant scene, and local restaurants receive statewide attention, several of them having become statewide chains.

The Sandia Peak Tramway, adjacent to Albuquerque, is the world's second-longest passenger aerial tramway. It also has the world's third-longest single span. It stretches from the northeast edge of the city to the crestline of the Sandia Mountains. Elevation at the top of the tramway is roughly 10,300 ft (3,100 m) above sea level.

International Balloon Fiesta

The Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta takes place at Balloon Fiesta Park the first week of October. It is one of Albuquerque's biggest attractions. Hundreds of hot-air balloons are seen every day, and there is live music, arts and crafts, and food.[54]

Architecture

John Gaw Meem, credited with developing and popularizing the Pueblo Revival style, was based in Santa Fe but received an important Albuquerque commission in 1933 as the architect of the University of New Mexico. He retained this commission for the next quarter-century and developed the university's distinctive Southwest style.[18] : 317 Meem also designed the Cathedral Church of St. John in 1950.[55]

Albuquerque boasts a unique nighttime cityscape. Many building exteriors are illuminated in vibrant colors such as green and blue. The Wells Fargo Building is illuminated green. The DoubleTree Hotel changes colors nightly, and the Compass Bank building is illuminated blue. The rotunda of the county courthouse is illuminated yellow, while the tops of the Bank of Albuquerque and the Bank of the West are illuminated reddish-yellow. Due to the nature of the soil in the Rio Grande Valley, the skyline is lower than might be expected in a city of comparable size elsewhere.

Albuquerque has expanded greatly in area since the mid-1940s. During those years of expansion, the planning of the newer areas has considered that people drive rather than walk. The pre-1940s parts of Albuquerque are quite different in style and scale from the post-1940s areas. The older areas include the North Valley, the South Valley, various neighborhoods near downtown, and Corrales. The newer areas generally feature four- to six-lane roads in a 1 mile (1.61 km) grid. Each 1 square mile (2.59 km²) is divided into four 160-acre (0.65 km2) neighborhoods by smaller roads set 0.5 miles (0.8 km) between major roads. When driving along major roads in the newer sections of Albuquerque, one sees strip malls, signs, and cinderblock walls. The upside of this planning style is that neighborhoods are shielded from the worst of the noise and lights on the major roads. The downside is that it is virtually impossible to go anywhere without driving.

Parks and recreation

According to the Trust for Public Land, Albuquerque has 291 public parks as of 2017, most of which are administered by the city Parks and Recreation Department. The total amount of parkland is 42.9 square miles (111 km2), or about 23% of the city's total area—one of the highest percentages among large cities in the U.S. About 82% of city residents live within walking distance of a park.

Albuquerque has a botanical and zoological complex called the Albuquerque Biological Park, consisting of the Rio Grande Botanic Garden, Albuquerque Aquarium, Tingley Beach, and the Rio Grande Zoo.

Sports

The Albuquerque Isotopes are a minor league affiliate of the Colorado Rockies, having derived their name from The Simpsons season 12 episode "Hungry, Hungry Homer", which involves the Springfield Isotopes baseball team considering relocating to Albuquerque.[56][57] Prior to 2002, the Albuquerque Dukes were the city's minor league team. The team played at the Albuquerque Sports Stadium which was demolished to make room for the current Isotopes Park.

The Albuquerque Sol soccer club began play in USL League Two in 2014.[58] On June 6, 2018, the United Soccer League announced its latest expansion club with USL New Mexico, headquartered in Albuquerque. Albuquerque is also home to Jackson-Winkeljohn gym, a mixed martial arts (MMA) gym. Several MMA world champions and fighters, including Holly Holm and Jon Jones, train in that facility.[59][60] Roller sports are finding a home in Albuquerque as they hosted USARS Championships in 2015,[61] and are home to Roller hockey,[62] and Roller Derby teams.[63]

| Team | Sport | League | Venue | capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albuquerque Isotopes | Baseball | AAA PCL | Isotopes Park | 13,279 |

| New Mexico United | Soccer | USL Championship | Isotopes Park | 13,279 |

| Albuquerque Sol | Soccer | USL League Two | Ben Rios Field | 1,500 |

| Duke City Gladiators | Indoor Football | Champions Indoor Football | Tingley Coliseum | 11,571 |

| New Mexico Lobos | NCAA Division I FBS Football | Mountain West Conference | University Stadium | 42,000 |

| New Mexico Lobos (men and women) | NCAA Division I Basketball | Mountain West Conference | The Pit | 15,411 |

| Duke City Roller Derby | Roller Derby | Wells Park Community Center |

Government and politics

#3333FF #E81B23 #DDDDBB| Albuquerque registered voters as of July, 2016[64] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 123,594 | 40.03% | |||

| Republican | 104,662 | 34.13% | |||

| Unaffiliated and third party | 78,404 | 25.57% | |||

Albuquerque is a charter city.[65][66] City government is divided into an executive branch, headed by a mayor[65]: V and a nine-member council that holds the legislative authority.[65]: IV The form of city government is therefore mayor-council government. The mayor is Tim Keller a former state auditor and senator, who was elected in 2017.

The Mayor of Albuquerque holds a full-time paid elected position with a four-year term.[67] Albuquerque City Council members hold part-time paid positions and are elected from the nine districts for four-year terms, with four or five Councilors elected every two years.[68] Elections for mayor and Councilor are nonpartisan.[65]: IV.4 [66] Each December, a new Council President and Vice-President are chosen by members of the Council.[67] Each year, the mayor submits a city budget proposal for the year to the Council by April 1, and the Council acts on the proposal within the next 60 days.[65]: VII

The Albuquerque City Council is the legislative authority of the city, and has the power to adopt all ordinances, resolutions, or other legislation.[68] The council meets two times a month, with meetings held in the Vincent E. Griego Council Chambers in the basement level of Albuquerque/Bernalillo County Government Center.[69] Ordinances and resolutions passed by the council are presented to the mayor for his approval. If the mayor vetoes an item, the Council can override the veto with a vote of two-thirds of the membership of the Council.[65]: XI.3

The judicial system in Albuquerque includes the Bernalillo County Metropolitan Court.

Police department

The Albuquerque Police Department (APD) is the police department with jurisdiction within the city limits, with anything outside of the city limits being considered the unincorporated area of Bernalillo County and policed by the Bernalillo County Sheriff's Department. It is the largest municipal police department in New Mexico, and in September 2008 the US Department of Justice recorded the APD as the 49th largest police department in the United States.[70]

In November 2012, the United States Department of Justice launched an investigation into APD's policies and practices to determine whether APD engages in a pattern or practice of use of excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment and the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, 42 U.S.C. § 14141 ("Section 14141").[71] As part of its investigation, the Department of Justice consulted with police practices experts and conducted a comprehensive assessment of officers' use of force and APD policies and operations. The investigation included tours of APD facilities and Area Commands; interviews with Albuquerque officials, APD command staff, supervisors, and police officers; a review of numerous documents; and meetings with the Albuquerque Police Officers Association, residents, community groups, and other stakeholders.[72] When the Department of Justice concluded its investigation, it issued a scathing report that uncovered a "culture of acceptance of the use of excessive force" involving significant harm or injury by APD officers against people who posed no threat and which was not justified by the circumstances. The DOJ recommended a nearly complete overhaul of the department's use-of-force policies. Among several systematic problems at APD were an aggressive culture that undervalued civilian safety and discounted the importance of crisis intervention.[73]

Economy

| Largest employers in Albuquerque | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Kirtland Air Force Base |

| 2 | University of New Mexico |

| 3 | Sandia National Laboratories |

| 4 | Albuquerque Public Schools |

| 5 | Presbyterian Healthcare Services |

| 6 | City of Albuquerque (Government) |

| 7 | Lovelace–Sandia Health System |

| 8 | Presbyterian Medical Services |

| 9 | Intel Corporation |

| 10 | State of New Mexico (Government) |

| 11 | Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. |

Albuquerque lies at the center of the New Mexico Technology Corridor, a concentration of high-tech private companies and government institutions along the Rio Grande. Larger institutions whose employees contribute to the population are numerous and include Sandia National Laboratories, Kirtland Air Force Base, and the attendant contracting companies which bring highly educated workers to a somewhat isolated region. Intel operates a large semiconductor factory or "fab" in suburban Rio Rancho, in neighboring Sandoval County, with its attendant large capital investment. Northrop Grumman is located along I-25 in northeast Albuquerque, and Tempur-Pedic is located on the West Mesa next to I-40.

The solar energy and architectural-design innovator Steve Baer located his company, Zomeworks, to the region in the late 1960s; and Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia, and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory cooperate here in an enterprise that began with the Manhattan Project. In January 2007, Tempur-Pedic opened an 800,000-square-foot (74,000 m2) mattress factory in northwest Albuquerque. SCHOTT Solar, Inc., announced in January 2008 they would open a 200,000-square-foot (19,000 m2) facility manufacturing receivers for concentrated solar thermal power plants (CSP) and 64MW of photovoltaic (PV) modules. The facility closed in 2012.

Forbes magazine rated Albuquerque as the best city in America for business and careers in 2006[74] and as the 13th best (out of 200 metro areas) in 2008.[75] The city was rated seventh among America's Engineering Capitals in 2014 by Forbes magazine.[76] Albuquerque ranked among the Top 10 Best Cities to Live by U.S. News & World Report in 2009[77] and was recognized as the fourth best place to live for families by the TLC network.[78] It was ranked among the Top Best Cities for Jobs in 2007 and among the Top 50 Best Places to Live and Play by National Geographic Adventure.[79][80]

Education

Albuquerque is home to the University of New Mexico, the largest public flagship university in the state. UNM includes a School of Medicine which was ranked in the top 50 primary care-oriented medical schools in the country.[81] Central New Mexico Community College is a county-funded junior college serving new high school graduates and adults returning to school.

Albuquerque is also home to the following programs and non-profit schools of higher learning: Southwest University of Visual Arts, Southwestern Indian Polytechnic Institute, Trinity Southwest University, the University of St. Francis College of Nursing and Allied Health Department of Physician Assistant Studies, and the St. Norbert College Master of Theological Studies program.[82] The Ayurvedic Institute, one of the first Ayurveda colleges specializing in Ayurvedic medicine outside of India was established in the city in 1984. Other state and not-for-profit institutions of higher learning have moved some of their programs into Albuquerque. These include: New Mexico State University, Highlands University, Lewis University, Wayland Baptist University, and Webster University. Several for-profit technical schools including Brookline College, Pima Medical Institute, National American University, Grand Canyon University, the University of Phoenix and several barber/beauty colleges have established their presence in the area.

Albuquerque Public Schools (APS), one of the largest school districts in the nation, provides educational services to almost 100,000 children across the city. Schools within APS include both public and charter entities. Numerous accredited private preparatory schools also serve Albuquerque students. These include various pre-high school religious (Christian, Jewish, Islamic) affiliates and Montessori schools, as well as Menaul School, Albuquerque Academy, St. Pius X High School, Sandia Preparatory School, the Bosque School, Evangel Christian Academy, Hope Christian School, Hope Connection School, Shepherd Lutheran School,[83] Temple Baptist Academy, and Victory Christian. Accredited private schools serving students with special education needs in Albuquerque include: Desert Hills, Pathways Academy, and Presbyterian Ear Institute Oral School. The New Mexico School for the Deaf runs a preschool for children with hearing impairments in Albuquerque.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Main highways

Some of the main highways in the metro area include:

- Pan-American Freeway:[84]: 248 More commonly known as Interstate 25 or "I-25", it is the main north–south highway on the city's eastern side of the Rio Grande. It is also the main north–south highway in the state (by connecting Albuquerque with Santa Fe and Las Cruces) and a plausible route of the eponymous Pan American Highway. Since Route 66 was decommissioned in the 1980s, the only remaining US highway in Albuquerque, unsigned US-85, shares its alignment with I-25. US-550 splits off to the northwest from I-25/US-85 in Bernalillo.

Aerial view of Interstate 40 - Coronado Freeway:[84]: 248 More commonly known as Interstate 40 or "I-40", it is the city's main east–west traffic artery and an important transcontinental route. The freeway's name in the city is in reference to 16th century conquistador and explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado.

- Paseo del Norte: (aka; New Mexico State Highway 423): This 6-lane controlled-access highway is approximately five miles north of Interstate 40. It runs as a surface road with at-grade intersections from Tramway Blvd (at the base of the Sandia Mountains) to Interstate 25, after which it continues as a controlled-access freeway through Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, over the Rio Grande to North Coors Boulevard. Paseo Del Norte then continues west as a surface road through the Petroglyph National Monument until it reaches Atrisco Vista Blvd and the Double Eagle II Airport. The interchange with Interstate 25 was reconstructed in 2014 to improve traffic flow.[85]

- Coors Boulevard: Coors is the main north-south artery to the west of the Rio Grande in Albuquerque. There is one full interchange where it connects with Interstate 40; The rest of the route connects to other roads with at-grade intersections controlled by stoplights. The Interstate 25 underpass has no access to Coors. Parts of the highway have sidewalks, bike lanes, and medians, but most sections have only dirt shoulders and a center turn lane. To the north of Interstate 40, part of the route is numbered as State Highway 448, while to the south, part of the route is numbered as State Highway 45.

- Rio Bravo Boulevard: The main river crossing between Westside Albuquerque and the Sunport, Rio Bravo is a four-lane divided highway that runs from University Boulevard in the east, through the South Valley, to Coors Boulevard in the west where it is contiguous with Dennis Chaves Blvd. It follows NM-500 for its entire route.

- Central Avenue: Central is one of the historical routings of Route 66, it is no longer a main through highway, its usefulness having been supplanted by Interstate 40.[84]: 248

- Alameda Boulevard: The main road between Rio Rancho and North Albuquerque, Alameda Blvd. stretches from Tramway Rd. to Coors. Blvd. The route is designated as the eastern portion of NM-528.

- Tramway Boulevard: Serves as a bypass around the northeastern quadrant, the route is designated as NM-556. Tramway Boulevard starts at I-25 near Sandia Pueblo, and heads east as a two-lane road. It turns south near the base of the Sandia Peak Tramway and becomes an expressway-type divided highway until its terminus near I-40 and Central Avenue by the western entrance to Tijeras Canyon.

The interchange between I-40 and I-25 is known as the "Big I".[84]: 248 Originally built in 1966, it was rebuilt in 2002. The Big I is the only five-level stack interchange in the state of New Mexico.

Bridges

There are six road bridges that cross the Rio Grande and serve the municipality on at least one end if not both. The eastern approaches of the northernmost three all pass through adjacent unincorporated areas, the Village of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, or the North Valley. In downstream order they are:

- Alameda Bridge

- Paseo del Norte Bridge

- Montaño Bridge

- I-40 Bridge

- Central at Old Town Bridge

- Barelas Bridge

Two more bridges serve urbanized areas contiguous to the city's perforated southern boundary.

- Rio Bravo Bridge (NM-500)

- I-25 Bridge (near Isleta Pueblo)

Rail

The state owns most of the city's rail infrastructure which is used by a commuter rail system, long distance passenger trains, and the freight trains of the BNSF Railway.

Freight service

BNSF Railway operates a small yard operation out of Abajo yard, located just south of the Cesar E. Chavez Ave. overpass and the New Mexico Rail Runner Express yards. Most freight traffic through the Central New Mexico region is processed via a much larger hub in nearby Belen, New Mexico.

Intercity rail

Amtrak's Southwest Chief, which travels between Chicago and Los Angeles, serves the Albuquerque area daily with one stop in each direction at the Alvarado Transportation Center in downtown.

Commuter rail

The New Mexico Rail Runner Express, a commuter rail line, began service between Sandoval County and Albuquerque in July 2006 using an existing BNSF right-of-way which was purchased by New Mexico in 2005. Service expanded to Valencia County in December 2006 and to Santa Fe on December 17, 2008. Rail Runner now connects Santa Fe, Sandoval, Bernalillo, and Valencia Counties with thirteen station stops, including three stops within Albuquerque.[86] The trains connect Albuquerque to downtown Santa Fe with eight roundtrips per weekday. The section of the line running south to Belen is served less frequently.[87]

Local mass transit

Albuquerque was one of two cities in New Mexico to have had electric street railways. Albuquerque's horse-drawn streetcar lines were electrified during the first few years of the 20th century. The Albuquerque Traction Company assumed operation of the system in 1905. The system grew to its maximum length of 6 miles (9.7 km) during the next ten years by connecting destinations such as Old Town to the west and the University of New Mexico to the east with the town's urban center near the former Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway depot. The Albuquerque Traction Company failed financially in 1915 and the vaguely named City Electric Company was formed. Despite traffic booms during the first world war, and unaided by lawsuits attempting to force the streetcar company to pay for paving, that system also failed later in 1927, leaving the streetcar's "motorettes" unemployed.[88]: 177–181

Today, Alvarado Station provides convenient access to other parts of the city via the city bus system, ABQ RIDE. ABQ RIDE operates a variety of bus routes, including the Rapid Ride express bus service.

In 2006, the City of Albuquerque under the administration of Mayor Martin Chavez had planned and attempted to "fast track" the development of a "Modern Streetcar" project. Funding for the US$270 million system was not resolved as many citizens vocally opposed the project. The city and its transit department maintain a policy commitment to the streetcar project.[89] The project would run mostly in the southeast quadrant on Central Avenue and Yale Boulevard.

As of 2011[update], the city is working on a study to develop a bus rapid transit system through the Central Ave. corridor. This corridor carried 44% of all bus riders in the ABQ Ride system, making it a natural starting point for enhanced service.[90] In 2017, the city moved forward with the plans, and began construction on Albuquerque Rapid Transit, or ART, including dedicated bus lanes between Coors and Louisiana Boulevards.[91]

Bicycle transit

Albuquerque has a well-developed bicycle network.[92] In and around the city there are trails, bike routes, and paths that provide the residents and visitors with alternatives to motorized travel. In 2009, the city was reviewed as having a major up and coming bike scene in North America.[93] The same year, the City of Albuquerque opened its first Bicycle Boulevard on Silver Avenue.[94] There are plans for more investment in bikes and bike transit by the city, including bicycle lending programs, in the coming years.[95]

Walkability

A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Albuquerque below average at 28th most walkable of the fifty largest U.S. cities.[96]

Airports

Albuquerque is served by two airports, the larger of which is Albuquerque International Sunport. It is located 3 mi (4.8 km) southeast of the central business district of Albuquerque. The Albuquerque International Sunport served 5,888,811 passengers in 2009.[97] Double Eagle II Airport is the other airport. It is primarily used as an air ambulance, corporate flight, military flight, training flight, charter flight, and private flight facility.[98]

Utilities

Energy

PNM Resources, New Mexico's largest electricity provider, is based in Albuquerque. They serve about 487,000 electricity customers statewide. New Mexico Gas Company provides natural gas services to more than 500,000 customers in the state, including the Albuquerque metro area.

Sanitation

The Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority is responsible for the delivery of drinking water and the treatment of wastewater. Trash and recycling in the city is managed by the City of Albuquerque Solid Waste Management Department.

South Side Water Reclamation Plant.

Healthcare

Albuquerque is the medical hub of New Mexico, hosting numerous state-of-the-art medical centers. Some of the city's top hospitals include the VA Medical Center, Presbyterian Hospital, Presbyterian Medical Services, Heart Hospital of New Mexico, and Lovelace Women's Hospital. The University of New Mexico Hospital is the primary teaching hospital for the state's only medical school and provides the state's only residency training programs, children's hospital, burn center and level I pediatric and adult trauma centers. The University of New Mexico Hospital is also the home of a certified advanced primary stroke center as well as the largest collection of adult and pediatric specialty and subspecialty programs in the state.

Media

The city is served by one major newspaper, the Albuquerque Journal, and several smaller daily and weekly papers, including the alternative Weekly Alibi. Albuquerque is also home to numerous radio and television stations that serve the metropolitan and outlying rural areas.

In popular culture

In film

Many Bugs Bunny cartoon shorts feature Bugs traveling around the world by burrowing underground; he gets lost quite often while traveling and remarks, while consulting a map, "I knew I should have made a left toin at Albukoykee." (Bugs first uses that line in 1945's Herr Meets Hare.)[99]

Some parts of the 1999 movie Pirates of the Silicon Valley were shot in Albuquerque.

Albuquerque has been featured in Hollywood movies such as Little Miss Sunshine (2006), Sunshine Cleaning (2008), and Brothers (2009).

The 2007 biker-buddy film Wild Hogs has its opening scenes that were set in Cincinnati, Ohio but were actually filmed in and around Albuquerque.

Marvel Studios' film The Avengers (2012) was mostly (>75%) filmed at the Albuquerque Studios.[100]

A Million Ways to Die in the West (2014), directed by Seth MacFarlane, was filmed in various areas in and around Albuquerque and Santa Fe.[101]

The 2013 film Force of Execution starring Steven Seagal is set and filmed in Albuquerque.

The escape scene from the film The Last Stand starring Arnold Schwarzenegger was filmed in downtown Albuquerque. The zip line sequence occurred between the Old City Hall Building at 400 Marquette Ave NW and the BBVA Compass building at 505 Marquette Ave NW.

In music

Musicians who have lived in Albuquerque include Jim Morrison, Glen Campbell, Bo Diddley, Demi Lovato, Eric McFadden, Rahim Al-Haj, and Bernadette Seacrest.

Music groups based in Albuquerque include A Hawk and A Hacksaw, Beirut, The Echoing Green, The Eyeliners, Hazeldine, Leiahdorus, Oliver Riot, Scared of Chaka, and The Shins.

Neil Young's song "Albuquerque" can be found on the album Tonight's the Night.

"Weird" Al Yankovic's song "Albuquerque" is on his album Running with Scissors.

In television

Albuquerque is the setting for the television shows In Plain Sight and Breaking Bad, with the latter significantly boosting tourism in the area.[102][103][104][105][106] Better Call Saul, a spinoff of Breaking Bad, is also set and shot in Albuquerque.[107]

Ethel Mertz, a character on the 1950s sitcom I Love Lucy, refers to Albuquerque as her hometown. Vivian Vance, the actress who played Ethel, actually was from Albuquerque.[108]

"Hungry, Hungry Homer", the 15th episode of the twelfth season of The Simpsons, features Albuquerque as the location where the owners of the Springfield Isotopes baseball team wish to relocate. The real Albuquerque Isotopes Minor League team's name was inspired by the episode.[109]

Notable people

Sister cities and twin towns

Albuquerque has ten sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International: [110]

- in Asia

- in Europe

Helmstedt, Lower Saxony, Germany

Helmstedt, Lower Saxony, Germany Alburquerque, Extremadura, Spain

Alburquerque, Extremadura, Spain

- in the Middle East

Rehovot, Israel

Rehovot, Israel

- in North America

Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico

Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico[111]

Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico[111]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ "American FactFinder". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates".

- ^ State & County QuickFacts Archived April 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Census.gov

- ^ "ABQ Trolley Co. – BURQUEÑOS". Abqtrolley.com. March 20, 2009. Archived from the original on May 15, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Albuquerque city, New Mexico". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder - Results". factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ Simmons, Marc (2003). Hispanic Albuquerque, 1706-1846. Albuquerque: UNM Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780826331601. Retrieved October 12, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Julyan, Robert Hixson (1996). The Place Names of New Mexico. Albuquerque: UNM Press. pp. 9–10. ISBN 9780826316899. Retrieved October 12, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dixon, Chris. "Up, Up and Gently Away". Retrieved September 15, 2018.

- ^ Barrett, Elinore M. (2002). Conquest and Catastrophe: Changing Rio Grande Pueblo Settlement Patterns in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Albuquerque: UNM Press. ISBN 9780826324139. Retrieved September 25, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "History of Sandia Pueblo". Sandia Pueblo website. Pueblo of Sandia. 2006. Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved January 17, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Seymour, Deni (2012). From the Land of Ever Winter to the American Southwest. University of Utah Press.

- ^ "About - Albuquerque Historical Society". Albuquerque Historical Society. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ^ "History". Nmallstar.com. Archived from the original on March 25, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.