Stateside Puerto Ricans

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| throughout the Northeast, Florida, Chicago Metro Area, and Cleveland Metro Area, with growing populations in other Southeastern States | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish and English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic, Minority Protestant | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Criollos · Mestizos · Mulattos · Lucumi · Taíno · African people · Europeans |

Stateside Puerto Ricans or Puerto Ricans, (Nuyorican for those born in New York), are American citizens of Puerto Rican origin, including those who migrated from Puerto Rico to the United States and those who were born outside of Puerto Rico to parents of Puerto Rican origin. Most stateside Puerto Ricans descend from a combination of Europeans (especially Spanish), the indigenous Taino peoples, and Africans, with later smaller waves of immigrants from Latin America, a small number of Asians (mostly Chinese), and non-Hispanic people from the United States.

Puerto Rico is a Commonwealth territory of the United States. The residents of the island have been United States citizens since 1917, through the Jones-Shafroth Act.

Puerto Ricans are the second largest Hispanic group in the US and comprise 9% of the Hispanic population in the US. Despite new demographic trends, New York City continues to be home to the largest Puerto Rican community in the United States, with Philadelphia having the second largest Puerto Rican community. A large portion of the Puerto Rican population in the United States reside in the Northeastern states and Florida, though there are significant Puerto Rican populations growing in states like Illinois, Ohio, North Carolina, Texas, California, Virginia, Maryland, and Georgia, among others.

Introduction

The 2010 Census indicated a population of 3,725,789 individuals on the island of Puerto Rico (95% of whom were Puerto Rican). There have been more Puerto Ricans in the states, than on the island since 2000. Today, there are 900,000 more Puerto Ricans stateside than on the island itself. This phenomenon of a diaspora outnumbering its own population is unprecedented in the hemisphere[citation needed]. However, this phenomenon has also had an impact on the island, especially in the political arena. Congressman Jose Serrano, who represents the largest Puerto Rican constituency in Congress, has been a strong advocate for Puerto Rican statehood. The last time Puerto Ricans voted on their political status was in 1998. During that vote, Statehood narrowly failed to "none of the above" (46%-50%). Another referendum for statehood is scheduled for November 2012. If Puerto Ricans were to vote for statehood, there is no guarantee that it would be granted, because only Congress has the authority to grant statehood. If Puerto Rico were admitted as a state, it would likely have five seats in the United States House of Representatives and two seats in the United States Senate. Both President Barrack Obama and 2012 Presidential candidate Mitt Romney have promised to support Puerto Rican statehood if that option is chosen by voters in Puerto Rico.[1][2][3] Its seven electoral votes would be considered safely Democratic and a Republican-controlled House may simply refuse to bring the matter to a vote[citation needed].

Identity

As a group, Puerto Ricans in the United States continue to have a strong connection to the people of Puerto Rico. A strong indicator of the Puerto Rican identity of stateside Puerto Ricans is their use of the Spanish language. Most Puerto Rican Americans also speak English. They make up the largest multi-lingual population in New York City[4] and other cities.

Puerto Ricans have been migrating to the United States since the 19th century and have a long history of collective social advocacy for their political and social rights and preserving their cultural heritage. In New York City, which has the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the United States, they began running for elective office in the 1920s, electing one of their own to the New York State Assembly for the first time in 1937.[5]

Important Puerto Rican institutions have emerged from this long history.[6] Aspira, a leader in the field of education, was established in New York City in 1961 and is now one of the largest national Latino nonprofit organizations in the United States.[7] There is also the National Puerto Rican Coalition in Washington, DC, the National Puerto Rican Forum, the Puerto Rican Family Institute, Boricua College, the Center for Puerto Rican Studies of the City University of New York at Hunter College, the Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education Fund, the National Conference of Puerto Rican Women, and the New York League of Puerto Rican Women, Inc., among others.

One indicator of the strength of Puerto Rican identity and pride is the annual National Puerto Rican Day Parade in New York City, which is the subject of the poetry work Empire of Dreams by islander Giannina Braschi. There are 50 other Puerto Rican parades throughout the country.

The government of Puerto Rico has a long history of involvement with the stateside Puerto Rican community.[8] In July 1930, Puerto Rico's Department of Labor established an employment service in New York City.[9] The Migration Division (known as the "Commonwealth Office"), also part of Puerto Rico’s Department of Labor, was created in 1948, and by the end of the 1950s, was operating in 115 cities and towns stateside.[10] The Department of Puerto Rican Affairs in the United States was established in 1989 as a cabinet-level department in Puerto Rico. The Commonwealth operates the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, which is headquartered in Washington, D.C., and has 12 regional offices throughout the United States.

The strength of stateside Puerto Rican identity is fueled by a number of factors. These include the large circular migration between the island and the United States, a long tradition of the government of Puerto Rico promoting its ties to those stateside, the continuing existence of racial-ethnic prejudice and discrimination in the United States, and high residential and school segregation.

Migration

Since 1493, Puerto Rico has been under the control of colonial powers. Even during Spanish rule, Puerto Ricans settled in the US. However, it was not until the end of the Spanish-American War that the huge influx of Puerto Rican workers to the US began. With its victory in 1898, the United States acquired Puerto Rico from Spain and has retained sovereignty ever since. The 1917 Jones–Shafroth Act made all Puerto Ricans US citizens, freeing them from immigration barriers. The massive migration of Puerto Ricans to the United States was the largest in the early and late 20th century.[11]

U.S political and economic interventions in Puerto Rico created the conditions for emigration, "by concentrating wealth in the hands of US corporations and displacing workers."[12] Policymakers promoted "colonization plans and contract labour programs to reduce the population. US employers, often with government support, recruited Puerto Ricans as a source of low-wage labour to the United States and other destinations."[13] Puerto Ricans migrated in search of higher-wage jobs, first to New York City, and later to other cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston,[14] Cleveland, Miami, Tampa, and Orlando.

New York City

Although the bulk of New York's Puerto Rican population migrated to the Bronx, the largest influx was to Spanish Harlem and Loisaida, in Manhattan, from the 1950s all the way up to 1980s. Labor recruitment was the basis of this particular community. In 1960, the number of stateside Puerto Ricans living in New York City as a whole was 88%, as 69% were living in East Harlem.[15] They helped others settle, find work, and build communities by relying on social networks containing friends and family. For a long time, Spanish Harlem (East Harlem) and Loisaida (Lower East Side) were the two major Puerto Rican communities in the city, but during the 1960s and 1970s predominately Puerto Rican neighborhoods started to spring up in the Bronx because of its proximity to East Harlem and in Brooklyn because of its proximity to the Lower East Side. Although half of the city's Puerto Rican population is in the Bronx, there are significant Puerto Rican communities in all five boroughs. The number of Puerto Rican residents in New York City, peaked at around 1980. At that time there were about 930,000 Puerto Rican residents in the city and about 80% of the Hispanic population was Puerto Rican, representing about 15% of the city's total population then. Now, both the number and percentage is significantly lower than it was in 1980.

Philippe Bourgois, an anthropologist who has studied Puerto Ricans in the inner city, suggests that "the Puerto Rican community has fallen victim to poverty through social marginalization due to the transformation of New York into a global city."[16] The Puerto Rican population in East Harlem and New York City as a whole remains the poorest among all migrant groups in US cities. As of 1973, about "46.2% of the Puerto Rican migrants in East Harlem were living below the federal poverty line."[17] The struggle for legal work and affordable housing remains fairly low and the implementation of favorable public policy fairly inconsistent. New York City's Puerto Rican community contributed to the creation of hip hop music, and to many forms of Latin music including Salsa and Freestyle. Puerto Ricans in New York created their own cultural movement, and cultural institutions such as the Nuyorican Poets Cafe.

It is often considered that the transformation of the US economy in 1973 and the 1980s mostly affected the entire Puerto Rican population of East Harlem. Puerto Ricans were first desired for cheaper labor. The economy shift from manufacturing to the service sector forcing these people into hard times, as many of them had worked in factories and relied on these particular jobs to support their families back home in Puerto Rico. The importance of factory jobs for a decent standard of living for these former rural workers proved crucial:

... labour in industrial production is still crucial and central to the global economy. However, the export of production from the center to the less media-visible periphery, and the development of the informational service economy, is an outright assault on working-class populations.[18]

Chicago

The Puerto Rican community in Chicago has a history that stretches back more than 70 years. The first small migration came in the 1930s, not from the island, but from New York City. The first large wave of migration occurred in the late 1940s. Starting in 1946, many people were recruited by Castle Barton Associates as low-wage non-union foundry workers and domestic workers. As soon as they were established in Chicago, many brought their families. Although the number of Puerto Ricans peaked at around 1980, at that time Chicago had about 240,000 Puerto Rican residents; before 1980, Puerto Ricans were actually the city's largest Hispanic group, though they quickly became overshadowed by a fast-growing Mexican population.

In the early 1950s there was a large concentration just north and west of downtown.It spread to Old Town and then a large barrio or neighborhood developed in Lincoln Park.By the 1960s, the Puerto Rican community was also centered in Wicker Park/West Town and Humboldt Park on the Northwest Side. There were also many Puerto Ricans in North Lawndale on the city's West Side. City-sponsored gentrification in Lincoln Park to increase the tax base and because it was prime real estate in proximity to Lake Michigan and to the Downtown Loop displaced the entire Puerto Rican community in the 1960s. This forced people due to the high rents that followed and the lack of social services to move west. Today Puerto Ricans are mainly present on the Northwest side of Chicago and once again are facing displacement[citation needed]. Still over half of Chicago's Puerto Rican community resides in Humboldt Park, which is sometimes nicknamed "Little Puerto Rico" or Paseo Boricua. Other neighborhoods with significant Puerto Rican populations are now also west and include Hermosa, Logan Square, and West Town. Puerto Ricans are no longer visible in Lincoln Park. However, in the process a national civil rights movement of Puerto Ricans lead by the Young Lords originated in Lincoln Park.

From the 1950s to the early 1990s, the Humboldt Park neighborhood was considered an economic dead zone by city planners and developers. It became a motherland to Chicago's Puerto Rican super-gangs such as the Puerto Rican Stones, Insane Spanish Cobras, Latin Eagles, Maniac Latin Disciples, and the Latin Kings, one of the largest Latino gangs in the country. Also, the Young Lords community activists hail from this area. They set up various neighborhood programs and are considered to be the Puerto Rican equivalent of the Black Panther Party. Despite the fact that there was a vital community of families, property owners, and businesses, many people from both the inside and out saw little opportunity. Chicago's Puerto Rican community largely participated in the Division Street Riots in 1966, which lasted for seven days, and was the only major Puerto Rican riot in the country.

However, in 1995, Division Street found new life when city officials and Latino leaders offered a symbolic gesture (due to a long history of neighborhood protests) to recognize the neighborhood and the residents' roots. They christened it "Paseo Boricua" and installed two metal Puerto Rican flags—each weighing 45 tons, measuring 59 feet (18 m) vertically, and stretching across the street—at each end of the strip. The struggling neighborhood transformed itself into one of the most vibrant Latino neighborhoods in Chicago, uniting the once fragmented Puerto Rican community, 601,890[when?] strong. The occupancy rate of the area rose to about 90 percent, and home prices stabilized. A culture center was established, and local Puerto Rican politicians relocated their offices to Division Street. Recently, the City of Chicago set aside money for Paseo Boricua property owners who want to restore their buildings' facades. The Humboldt Park Paseo Boricua neighborhood is the political and cultural capital of the Puerto Rican community in the Midwest and some say in the Puerto Rican Diaspora.

Philadelphia

Puerto Ricans represent the largest Latino community in Philadelphia, with over a century of settlement in the city. Puerto Ricans represent nearly 70% of Philadelphia's 190,000 Hispanics. Although U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans migrating to Philadelphia encountered racism, discrimination, and limited economic opportunities. Retaining strong ties to the island, they also worked hard to make a home here and build a community structure of businesses, organizations, houses of worship, and other institutions that have become the foundation of Latino life in the city. Throughout the 1950s, many Puerto Rican migrants settled east and west along Spring Garden Street. Puerto Ricans were not always welcome newcomers, however, and many faced prejudice and discrimination in their neighborhoods. As the Puerto Rican population continued to grow in the 1960s, it expanded east towards the Delaware River and north towards Lehigh Avenue. During the 1980s and 1990s, the Puerto Rican community grew further north into Olney and into the lower sections of the Northeast. The majority of Philadelphia's Puerto Rican population resides in North Philadelphia, and increasingly in lower Northeast Philadelphia. Though smaller yet still significant populations are present in other parts of the city.

Demographics of stateside Puerto Ricans

Between 1990 and 2000, the stateside Puerto Rican population grew by 12.5 percent, from 3.2 to 3.4 million. This growth rate was significantly higher than the 8.4 percent growth of Puerto Rico during this same period.

In the most recent census in 2010, there were 4,623,716 Puerto Rican Americans, both native and foreign born, representing 9.2% of all Hispanics in the US. About 53.1% identified themselves as white, which is the second largest population of all other major Hispanic groups. (However, 75% of Puerto Ricans in Puerto Rico self-identify themselves as white.) About 8.7% considered themselves black. 0.5% considered themselves Asian and 0.9% considered themselves Native American. The majority of Puerto Ricans are racially mixed, but that they do not feel the need to identify as such. Furthermore, Puerto Ricans, some of which may be of Black African, American Indian, and European ancestry may only identify themselves as mixed if having parents "appearing" to be of separate "races". (This may be true of non-Puerto Ricans or non-Hispanics also.) Since many Puerto Ricans are light-skinned, like other whites, most choose to identify as "white".[19] The US Census shows that the majority of Puerto Ricans have self-described themselves as "white". The racial identification issue of Puerto Ricans in the US is controversial and heatly debated, a cause of ethnic prejudice towards Puerto Ricans and also between those living Stateside and on the Island.[20][21]

Population by state

| State/Territory | Puerto Rican-Americans Population (2010 Census)[20][22] |

Percentage[23] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12,225 | 0.3 | ||

| 4,502 | 0.6 | ||

| 34,787 | 0.5 | ||

| 4,789 | 0.2 | ||

| 189,945 | 0.5 | ||

| 22,995 | 0.5 | ||

| 252,972 | 7.1 | ||

| 22,533 | 2.5 | ||

| 3,129 | 0.5 | ||

| 847,550 | 4.5 | ||

| 71,987 | 0.7 | ||

| 44,116 | 3.2 | ||

| 2,910 | 0.2 | ||

| 182,989 | 1.4 | ||

| 30,304 | 0.5 | ||

| 4,885 | 0.2 | ||

| 9,247 | 0.3 | ||

| 11,454 | 0.3 | ||

| 11,603 | 0.3 | ||

| 4,377 | 0.3 | ||

| 42,572 | 0.7 | ||

| 266,125 | 4.1 | ||

| 37,267 | 0.4 | ||

| 10,807 | 0.2 | ||

| 5,888 | 0.2 | ||

| 12,236 | 0.2 | ||

| 1,491 | 0.2 | ||

| 3,242 | 0.2 | ||

| 20,664 | 0.8 | ||

| 11,729 | 0.9 | ||

| 434,092 | 4.9 | ||

| 7,964 | 0.4 | ||

| 1,070,558 | 5.5 | ||

| 71,800 | 0.8 | ||

| 987 | 0.1 | ||

| 94,965 | 0.8 | ||

| 12,223 | 0.3 | ||

| 8,845 | 0.2 | ||

| 366,082 | 2.9 | ||

| 34,979 | 3.3 | ||

| 26,493 | 0.6 | ||

| 1,483 | 0.2 | ||

| 21,060 | 0.3 | ||

| 130,576 | 0.5 | ||

| 7,182 | 0.3 | ||

| 2,261 | 0.4 | ||

| 73,958 | 0.9 | ||

| 25,838 | 0.4 | ||

| 3,701 | 0.2 | ||

| 46,323 | 0.8 | ||

| 1,026 | 0.2 | ||

| USA | 4,623,716 | 1.5 |

Since 2000, the Puerto Rican population has increased by 1.2 million. The Northeast (including New England) gained 394,932 Puerto Ricans. Florida gained almost a similar amount, with 365,523 Puerto Ricans. A slowing of growth in the Puerto Rican population in the Northeast and a rapid rate of growth of Puerto Ricans in the South, especially Florida, tends to support the notion of Puerto Rican flight from the Northeast. The number of Puerto Ricans migrating from the island to the mainland has significantly increased over the past few years. The states with the highest net flow of Puerto Ricans from the island relocating there, include Florida, Pennsylvania, Texas, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Ohio, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland, between 2000 and 2010, these states were the major destinations for Puerto Ricans migrating from the island to the fifty states, and possibly remain so.[24] New York, remains a major destination for Puerto Rican migrants, though only a third of recent Puerto Rican arrivals went to New York.[25]

Although, Puerto Ricans constitute over 9 percent of Hispanics in the nation, there are some states where Puerto Ricans make up over half of the Hispanic population, including Connecticut where 57 percent of the state's Hispanics are of Puerto Rican descent and Pennsylvania where Puerto Ricans make up 53 percent of the Hispanics. Other states where Puerto Ricans make up a remarkably large portion of the Hispanic community include: Massachusetts where they make up 40 percent of all Hispanics, Rhode Island at 39 percent, New York at 34 percent, New Jersey at 33 percent, Delaware at 33 percent, Ohio at 27 percent, and Florida at 21 percent of all Hispanics in that state.[20][23] The U.S. States where Puerto Ricans were the largest Hispanic group were New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Hawaii.[20]

Even with such movement of Puerto Ricans from traditional to non-traditional states, the Northeast continues to dominate in both concentration and population.

The largest population of Puerto Ricans are situated in the following metropolitan areas (Source: Census 2010):

- New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-CT MSA - 1,177,430

- Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL MSA - 269,781

- Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD MSA - 238,866

- Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL MSA - 207,727

- Chicago-Joliet-Naperville, IL-IN-WI MSA - 188,502

- Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL MSA - 143,886

- Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH MSA - 115,087

- Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT MSA - 102,911

- Springfield, MA MSA - 87,798

- New Haven-Milford, CT MSA - 77,578

The Northeast

The Northeast is home to 2.5 million Puerto Ricans, comprising 54% of the Puerto Rican population nationwide. New York City has the largest population of Puerto Ricans in the country, followed by Philadelphia. In New York, the cities of Dunkirk and Amsterdam have the highest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the state. Puerto Rican populations are significant in New York City, Long Island, the Hudson Valley, especially Westchester County and the cities of Rochester and Buffalo. In Pennsylvania, one-third of Puerto Ricans reside in Philadelphia. However, Puerto Ricans are more concentrated in South Central Pennsylvania and the Lehigh Valley. This area, extending from Harrisburg to the New Jersey border is home to almost half of Puerto Ricans statewide. Cities along this stretch include York, Harrisburg, Lancaster, Lebanon, Reading, Allentown, and Bethlehem. In New Jersey, a slight majority of Puerto Ricans are located in North Jersey. Cities with significant populations include Newark, Jersey City, Paterson, and Elizabeth. The remaining half of Puerto Ricans are split evenly between Central Jersey and South Jersey. In Central Jersey, cities with large Puerto Rican populations include Trenton, Dover Township, and Perth Amboy. In South Jersey, cities include Camden, Vineland, Millville, and Atlantic City.

In New England, half of the Puerto Rican population is situated along the Interstate-91 corridor, extending from New Haven in Connecticut to Holyoke in Massachusetts. The highest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the US can be found in Holyoke. Cities situated along the corridor include Meriden, New Britain, Hartford, Chicopee in Connecticut, and Springfield, Massachusetts. In Connecticut, Puerto Ricans are the largest Hispanic group in four of the five largest cities. Outside the Interstate-91 corridor, additional cities with significant Puerto Ricans include Bridgeport, New London, and Willimantic. In Massachusetts, Puerto Ricans continue to dominate in the central part of the state in places like Fitchburg, Lowell, and Worcester. However, Puerto Rican presence in Lawrence and Lynn is overshowed by a larger Dominican presence. Puerto Ricans also exist in large numbers in Boston and Chelsea, yet a growing Central American and Dominican population has impacted Puerto Rican prominence. In Rhode Island, Puerto Ricans are half of the Dominican population in Providence and are gradually being replaced by a growing Guatemalan population. Statewide, Puerto Ricans are most prominent in Woonsocket. Within the metro area, Puerto Ricans continue to be the largest Hispanic group, largely due to Puerto Rican dominance in Fall River and New Bedford, both of which are in Massachusetts.

The South

The South is home to 1.3 million Puerto Ricans, comprising 28% of the Puerto Rican population nationwide. Florida is home to two-thirds of the Puerto Rican population in the South. The I-4 corridor, extending from Daytona Beach to Tampa, is home to 500,000 Puerto Ricans, making this the largest population of Puerto Ricans outside of Greater New York. Places along the corridor include Deltona, Sanford, Altamonte Springs, Orlando, Kissimmee, Saint Cloud, and Poinciana, FL. Osceola County is the only only county in the country where Puerto Ricans are the largest ancestral group. Puerto Ricans are also the majority Hispanic group in Volusia County. The I-4 corridor is politically considered the swing section of the state, yet Puerto Rican growth has created a Democratic registration advantage. Central Florida has the fastest growing Puerto Rican community in the country. Puerto Rican growth in Central Florida has also had a direct impact on the uninterrupted influence Cubans once had. Elsewhere in Florida, Puerto Ricans are largely present in South Florida, yet are largely overlooked by Cuban dominance, with significant populations in Miami, and West Palm Beach. Since the early 2000's, a thriving Puerto Rican community has been growing in the Jacksonville-Savannah metropolitan area. Other Florida cities with sizeable communities include Ocala, Palm Bay, Cape Coral, and Lehigh Acres

In Delaware, the is a significant Puerto Rican population in New Castle County, especially Wilmington. In Maryland, there is a relatively small, yet growing Puerto Rican population in Baltimore, and in many smaller cities throughout Central Maryland. In Virginia, about half of the Puerto Rican population is in many cities in the Hampton Roads area, including Norfolk, and Virginia Beach. The remaining half mainly located in Northern Virginia, particularly near the District of Columbia. In North Carolina, there is Puerto Rican populations in Fayetteville, Raleigh, and Charlotte. In Georgia, there is a small Puerto Rican population in Atlanta, and in areas in the Southeastern part of the state near Jacksonville.

The Midwest

The Midwest is home to 435,000 Puerto Ricans, comprising 9% of the Puerto Rican population nationwide. A little less than two-thirds of the population can be found in three Metropolitan Statistical Areas: Chicago, Cleveland, and Milwaukee. Only in Cleveland are Puerto Ricans the largest Hispanic group. In Illinois, 56% of the Puerto Rican population is located in the city of Chicago. The Humboldt Park neighborhood is home to the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the Midwest. In Ohio, almost two-thirds of Puerto Ricans can be found in the Cleveland Metro. Cleveland has the largest population of Puerto Ricans in the state. There are many other Ohio cities with significant Puerto Rican populations, particularly in Northeast Ohio, including Lorain, Elyria, Youngstown, Campbell, Akron, and Shaker Heights. Columbus also has a small, yet rapidly growing Puerto Rican population. Toledo has a small Puerto Rican population. Lorain has the highest percentage of Puerto Ricans of any city west of the Appalachian mountains. In Wisconsin, 53% of the Puerto Rican population resides in the city of Milwaukee.

Elsewhere in the Midwest, in Indiana, Northwest Indiana has many Puerto Ricans in cities such as Hammond and East Chicago. The city of Indianapolis also has a small population. In Michigan, the Puerto Rican population is relatively small, yet present in Detroit, Grand Rapids, and Pontiac.

The West

The West is home to 372,000 Puerto Ricans, comprising 8% of the Puerto Rican population nationwide. The most significant presence of Puerto Ricans can be found in Hawaii on the Big Island. The windward side of the island, along the coast of Hilo has the largest concentration of Puerto Ricans in the West. Hawaii is the only state outside the Northeast where Puerto Ricans are the largest Hispanic group. On the island of Oahu, Puerto Ricans are equally present, yet less concentrated. In California, Puerto Ricans are largely absent, being only the fourth largest Hispanic group, and even overshadowed by many Asian ethnicities. Yet there are Puerto Ricans in the cities of Los Angeles, San Diego, San Jose, San Francisco, Sacramento, Santa Clarita, Long Beach, Hayward, and Oakland.

In Arizona, Puerto Ricans are less visible, yet have a growing population in Phoenix. In Nevada, Las Vegas and North Las Vegas both have a growing Puerto Rican population.

Communities with largest Puerto Rican population

- New York City: 723,621 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[20] compared to 789,172 in 2000,[26] decrease of 65,551; representing 8.9% of the city's total population and 32% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group.

- Philadelphia: 121,643 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[20] compared to 91,527 in 2000,[26] increase of 30,116; representing 8.0% of the city's total population and 68% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's largest Hispanic group.

- Chicago: 102,703 Puerto Rican residents, as of 2010;[20] compared to 113,055 in 2000,[26] decrease of 10,352; representing 3.8% of the city's total population and 15% of the city's Hispanic population, are the city's second largest Hispanic group.

The top 25 US communities with the highest populations of Puerto Ricans (Source: Census 2010)

- New York, NY - 723,621

- Philadelphia, PA - 121,643

- Chicago, IL - 102,703

- Springfield, MA - 50,798

- Hartford, CT - 41,995

- Newark, NJ - 35,993

- Bridgeport, CT - 31,881

- Orlando, FL - 31,201

- Boston, MA - 30,506

- Allentown, PA - 29,640

- Cleveland, OH - 29,286

- Reading, PA - 28,160

- Rochester, NY - 27,734

- Jersey City, NJ - 25,677

- Waterbury, CT - 24,947

- Milwaukee, WI - 24,672

- Tampa, FL - 24,057

- Camden, NJ - 23,759

- Worcester, MA - 23,074

- Buffalo, NY - 22,076

- New Britain, CT - 21,914

- Jacksonville, FL - 21,128

- Paterson, NJ - 21,015

- New Haven, CT - 20,505

- Yonkers, NY - 19,875

Communities with high percentages of Puerto Ricans

The top 25 US communities with the highest percentages of Puerto Ricans as a percent of total population (Source: Census 2010)

- Holyoke, MA - 44.70%

- Buenaventura Lakes, FL - 44.55%

- Azalea Park, FL - 36.50%

- Poinciana, FL - 35.82%

- Meadow Woods, FL - 35.11%

- Hartford, CT - 33.66%

- Springfield, MA - 33.19%

- Kissimmee, FL - 33.06%

- Reading, PA - 31.97%

- Camden, NJ - 30.72%

- New Britain, CT - 29.93%

- Lancaster, PA - 29.23%

- Vineland, NJ - 26.74%

- Union Park, FL - 25.81%

- Allentown, PA - 25.11%

- Windham, CT - 23.99%

- Lebanon, PA - 23.87%

- Perth Amboy, NJ - 23.79%

- Southbridge, MA - 23.08%

- Harlem Heights, FL - 22.63%

- Waterbury, CT - 22.60%

- Lawrence, MA - 22.20%

- Dunkirk, NY - 22.14%

- Bridgeport, CT - 22.10%

- Sky Lake, FL - 22.09%

−

The 10 large cities (over 200,000 in population) with the highest percentages of Puerto Rican residents include[23]:

- Rochester, New York: 13.2 percent

- Orlando, Florida: 13.1 percent

- Newark, New Jersey: 13.0 percent

- Jersey City, New Jersey: 10.4 percent

- New York City, New York: 8.9 percent

- Buffalo, New York: 8.4 percent

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: 8.0 percent

- Cleveland, Ohio: 7.4 percent

- Tampa, Florida: 7.2 percent

- Boston, Massachusetts: 4.9 percent

Migration trends

However, despite these dramatic growth rates, it was the decline in the Puerto Rican population in New York City during the 1990s that became a focus of discussion of many Puerto Ricans following Census 2000, along with the dramatic growth in Florida. During this period, the city’s Puerto Rican population dropped by over 100,000, or 12 percent. Because of this, New York was the only state to register a decrease in its Puerto Rican population during this time period (a phenomenon limited to the three biggest counties in New York City). This is a good example of how complex Puerto Rican demographics have become.[27] While overall there was a significant drop citywide in the 1990s, there was also significant growth in two of its five boroughs (or counties). In addition, despite this decline, New York City remains a major hub for migration from Puerto Rico and within the United States. Numbering over 720,000, New York City’s Puerto Rican community remains its largest Latino population group.

Four other major cities experienced a decrease in Puerto Rican residents from 1990-2000:

- Chicago, Illinois: -6,811 (a 2 percent drop)

- Jersey City, New Jersey: -13,567 (4 percent)

- Newark, New Jersey: -11,895, (5 percent)

- Paterson, New Jersey: -3,567 (13 percent)

The reasons for and impact of these declines are not well understood. Especially in the New York case, this has been the subject of much speculation but little serious analysis to date.[28] Between New York City, Philadelphia, and Chicago, the cities with the three largest Puerto Rican populations, Philadelphia is the only one that actually seen an increase, while the other two seen decreases. This is probably due to Philadelphia's proximity to New York City, and its cheaper cost of living.[28]

To put this population decline in a broader context, it is important to note that beyond these major cities, the stateside Puerto Rican population dropped in 1990-2000 in 164 other smaller cities throughout the United States, 10.8 percent of the 1,503 cities and other places surveyed by the 2000 Census (CDPs or Census-designated places). Of the ten places in the country with the highest percentage drop in their Puerto Rican population, five were in California, two each in Florida and New Jersey, and one in Massachusetts. None were in the Midwest. The five places with the largest 1990-2000 declines were:

- Olympia Heights, Florida: -72.4 percent

- Marina, California: -59.0 percent

- Seaside, California: -55.1 percent

- Baldwin Park, California: -48.4 percent

- Pompano Beach Highlands, Florida: -43.8 percent

Dispersion

Like other groups, the theme of "dispersal" has had a long history with the stateside Puerto Rican community.[29] This history extends from the early concerns of overpopulation of Puerto Rico to those in the 1940s and 1950s about the need to disperse the rapidly growing Puerto Rican population dramatically concentrating in New York City, Chicago and other US urban centers after World War II.

More recent demographic developments appear at first blush as if the stateside Puerto Rican population has been dispersing in greater numbers. However, upon closer examination, it is a process probably best described as a “reconfiguration” or even the “nationalizing” of this community throughout the United States.[30]

New York City was the center of the stateside Puerto Rican community for most of the 20th century. With the 2000 Census, this picture changed in dramatic ways. New York City was once home to over 80 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans and a place where Puerto Ricans were the majority of its Latino population. By 2000, Puerto Ricans in New York City had dropped only 23 percent of all stateside Puerto Ricans, and made up 37 percent of the city’s Latino population. Nevertheless, they remain the largest Latino group in the city. Numbering close to 800,000 in 2000, their population is almost double that of Puerto Rico’s capital city, San Juan (estimated at 433,412 in 2002 by the Census Bureau).

The dramatic growth of the Puerto Rican population in Florida has generated considerable attention, especially given its important political implications for US presidential elections. Between 1990 and 2000, their numbers almost doubled from 247,016 to 482,027 (a 95.1 percent increase). According to the Current Population Survey, in 2003, the Puerto Rican population in the state was estimated to be 760,127, a growth of 57.7 percent since 2000.

However, as already stated, it is not at all clear whether these settlement changes can be characterized as simple population dispersal. It is a fact that Puerto Rican population settlements today are less concentrated than they were in places like New York City, Chicago and a number of cities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Jersey. However, 67.0 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans in 2003 still resided in the two most traditional areas, the Northeast and Midwest.

The most dramatic Puerto Rican population growth in the 1990s, as it was for Latinos as a whole, took place in smaller cities and towns, such as Allentown, Pennsylvania,[31] and other metro areas, such as Houston, Texas, the DC Metro Area, and the Hartford, Connecticut-Springfield, Massachusetts region.[citation needed] But while this type of growth outside of central cities is usually associated with suburbanization and upward mobility, in the Puerto Rican case, this has not been the case. While there was an element of upward mobility, there was also a dispersal of the poor and low wage workers. At the point when stateside Puerto Ricans began relocating to the suburbs, these areas had begun in general to take on many of the negative characteristics of the urban centers: housing and school segregation, poverty, rising crime and so on.

Rather than simple dispersal, what may be occurring is a reconcentration and an increasingly complex migration circuit for stateside Puerto Ricans. Undoubtedly driven largely by the current powerful force of globalization and its attendant economic restructuring, this redistribution of such a large portion of the stateside and island Puerto Rican populations is creating a significant social reconfiguration, with an uncertain long-term impact.

Concentration

Despite these significant population movements, even in 2000, the Puerto Rican population of cities outside of the traditional regions of the Northeast and Midwest did not rank high; Tampa and Orlando, both in Florida, were only 20th and 23rd, respectively. Puerto Ricans continued to be one of the most urbanized groups in the United States, with 55.8 percent living in central cities in 2003. This was more than double the 25 percent of non-Latinos and higher than Mexicans (43.1 percent), Cubans (22.3 percent), and Central/South Americans (47.9 percent).

Residential segregation is a cause of stateside Puerto Rican population concentration. While blacks are the most residentially segregated group in the United States, stateside Puerto Ricans are the most segregated among US Latinos.[32] Residential segregation is a serious problem related primarily to housing discrimination, especially for groups like Puerto Ricans, who have been migrating stateside for close to a century. Residential concentrations are associated with high poverty conditions and a host of other social problems, including low-performing schools, poor health and low-paying jobs. Using a measure of degree of segregation called the Index of Dissimilarity, for which a score of 60 or above indicates a high level of segregation, Puerto Ricans exceeded this level in nine major metropolitan areas. They were the most segregated in the following six metro areas in 2000:

- Bridgeport, Connecticut (score of 73)

- Hartford, Connecticut (70)

- New York City (69)

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (69)

- Newark, New Jersey (69)

- Cleveland-Lorain-Elyria, Ohio (68)

Stateside Puerto Ricans also find themselves concentrated in a third interesting way — they are disproportionately clustered in what has been called the "Boston-New York-Washington Corridor" along the East Coast. This area, coined a "megalopolis" by geographer Jean Gottman in 1956, is the largest and most affluent urban corridor in the world, being described as a "node of wealth ... [an] area where the pulse of the national economy beats loudest and the seats of power are well established."[33] With major world class universities clustered in Boston and stretching throughout this corridor, the economic and media power and international power politics in New York City, and the seat of the federal government in Washington, DC, this is a major global power center.

The actual and potential impact that stateside Puerto Ricans are and can have on the United States and globally because of their significant presence in this Boston-New York-Washington megalopolis has been considerable. It is a locational advantage that can best be leveraged if this community is able to develop the leadership and infrastructure to exploit it. It certainly helps to account for the most disproportionate projection of stateside Puerto Rican images globally through the media and institutions of higher education since the "great migration" of the 1950s.[citation needed]

Segmentation

These changes in the settlement patterns of stateside Puerto Ricans between so-called traditional and new areas have resulted in a greater economic and social segmentation or polarization of this population along spatial lines. The Northeast, which in 2003 was home to 59.2 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans, was also where 88.5 percent of them receiving public assistance lived. The average household income in 2002 of $42,032 was the lowest of any major racial-ethnic group in the Northeast; this was the only region where it was lower than the national average for stateside Puerto Ricans. The Northeast was also the region where stateside Puerto Ricans had the lowest homeownership rate, 31.9 percent, aside from California (the two most expensive housing markets in the United States in general).

Because of its greater visibility and the dramatic growth of its Puerto Rican population, Florida is usually identified as the main engine behind this polarization. However, there are more dramatic differences in socioeconomic indicators between the Northeast and states like California, Texas and Hawaii. This is also the case for states like New Jersey and Illinois, which are in the more traditional Puerto Rican settlement regions. The regional socioeconomic polarization is more complex than it may appear at first glance. While the greater affluence of the Puerto Rican population in states like California (for example the Coachella Valley) and Texas (such as Austin) may be well-established, the future of a state like Florida (especially the Orlando metro area) in this regard is not at all clear, given the rapidity and size of the migration and the different economic forces and labor markets at play.

While the 1990-2000 population growth rate of stateside Puerto Ricans of 24.9 percent was impressive compared to the 13.1 percent growth for the overall population, it was less than half of the growth rate of the total Latino population of 57.9 percent. In cities like New York, the Puerto Rican share of the Latino population decreased, though in Florida it increased. Overall, stateside Puerto Ricans make up about from 9 to 10 percent of the national Latino population.

These shifts in the relative sizes of Latino populations have also changed the role of the stateside Puerto Rican community.[34] In many cases, Puerto Rican community leaders have become major advocates for immigration reform despite the fact that Puerto Ricans are US citizens. In some cases, because this community has had a longer history in dealing with the political system, the increasing numbers of Puerto Ricans elected and appointed government officials play gate-keeping and other roles in terms of the growing non-Puerto Rican Latino communities. Thus, many long established Puerto Rican institutions have had to revise their missions (and, in some cases, change their names) to provide services and advocacy on behalf of non-Puerto Rican Latinos. Some have seen this as a process that has made the stateside Puerto Rican community nearly invisible as immigration and a broader Latino agenda seem to have taken center stage, while others view this is a great opportunity for stateside Puerto Ricans to increase their influence and leadership role in a larger Latino world.

Socioeconomic conditions

Income

The stateside Puerto Rican community has usually been characterized as being largely poor and part of the urban underclass in the United States. Studies and reports over the last fifty years or so have documented the high poverty status of this community.[35] However, the picture at the start of the 21st century also reveals significant socioeconomic progress and a community with a growing economic clout.[36]

In 2002, the average individual income for stateside Puerto Ricans was $33,927,[citation needed] only 68.7 percent that of whites ($48,687) and below the average of Asians ($49,981), Cubans ($38,733) and Mexicans ($38,200). [citation needed] However, it was higher than that of Dominicans ($28,467), and Central and South Americans ($30,444).[citation needed] In 2002, there were an estimated 24,450 stateside Puerto Ricans with individual incomes of $100,000 or more, compared to 4,059 a decade earlier. [citation needed]

The Latino market and remittances to Puerto Rico

The combined income for stateside Puerto Ricans in 2002 was $54.5 billion. This exceeded the total personal income of Puerto Rico, which was $42.6 billion in 2000. This is a significant share of the large and growing Latino market in the United States that has been attracting increased attention from the media and the corporate sector. In the last decade or so, major corporations have discovered the so-called "urban markets" of blacks and Latinos that had been neglected for so long. This has spawned a cottage industry of marketing firms, consultants and publications that specialize in the Latino market.

One important question this raises is the degree to which stateside Puerto Ricans contribute economically to Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rico Planning Board estimated that remittances totaled $66 million in 1963.[37] The only recent study that could be identified that examines the issue of remittances by stateside Puerto Ricans to Puerto Rico limited itself to migrants (those living stateside who were born on the island) and found that 38 percent of them indicated they sent money to Puerto Rico, averaging $1,179 per year per person (these are unpublished figures not included in the report that was released by DeSipio, et al. 2003). Using 2002 figures for island-born adult stateside Puerto Ricans, this would represent $417.8 million in remittances annually from that group alone. Since the island-born represented only 34 percent of the stateside Puerto Rican population in 2003, actual remittances from the entire community are probably more than double this number, possibly approaching or exceeding $1 billion a year. It is also important to keep in mind that these are family remittances and do not include investments in businesses and property in Puerto Rico, visitor expenditures and the like by stateside Puerto Ricans.

The full extent of the stateside Puerto Rican community’s contributions to the economy of Puerto Rico is not known, but it is clearly significant. The role of remittances and investments by Latino immigrants to their home counties has reached a level that it has received much attention in the last few years, as countries like Mexico develop strategies to better leverage these large sums of money from their diasporas in their economic development planning.[38] Yet, the income disparity between the stateside community and those living on the island is not as great as those of other Latin-American countries, and the direct connection between second-generation Puerto Ricans and their relatives is not as conducive to direct monetary support. Many Puerto Ricans still living in Puerto Rico also remit to family members who are living stateside.

Gender

The average income in 2002 of stateside Puerto Rican men was $36,572, while women earned an average $30,613, 83.7 percent that of the men. Compared to all Latino groups, whites, and Asians, stateside Puerto Rican women came closer to achieving parity in income to the men of their own racial-ethnic group. In addition, stateside Puerto Rican women had incomes that were 82.3 percent that of white women, while stateside Puerto Rican men had incomes that were only 64.0 percent that of white men. Stateside Puerto Rican women were closer to income parity with white women than were women who were Dominicans (58.7 percent), Central and South Americans (68.4 percent), but they were below Cubans (86.2 percent), "other Hispanics" (87.2 percent), blacks (83.7 percent), and Asians (107.7 percent).

Stateside Puerto Rican men were in a weaker position in comparison with men from other racial-ethnic groups. They were closer to income parity to white men than men who were Dominicans (62.3 percent), and Central and South Americans (58.3 percent). Although very close to income parity with blacks (65.5 percent), stateside Puerto Rican men fell below Mexicans (68.3 percent), Cubans (75.9 percent), other Hispanics (75.1 percent), and Asians (100.7 percent).

Educational attainment

Stateside Puerto Ricans, along with other US Latinos, have experienced the long-term problem of a high school dropout rate that has resulted in relatively low educational attainment.[6] Of those 25 years and older, 63.2 percent graduated from high school, compared to 84.0 percent of whites, 73.6 percent of blacks, 83.4 percent of Asians, 68.7 percent of Cubans, and 72.6 percent of other Latinos.[citation needed] The rate, however, exceeded that of Mexicans (48.7 percent), Dominicans (51.7 percent) and Central and South Americans (60.4 percent).[citation needed]

While in Puerto Rico, according to the 2000 Census, 24.4 percent of those 25 years and older had a four-year college degree, for stateside Puerto Ricans the figure was only 9.9 percent. By 2003, it had increased to 13.1 percent, below the rate for whites (26.1 percent), blacks (14.4 percent) and Asians (43.3 percent). Among Latinos, only Mexicans (6.2 percent) fared worse, with other groups having higher rates: Dominicans (10.9 percent), Cubans (19.4 percent), Central and South Americans (16.0 percent) and other Latinos (16.1 percent).[citation needed]

Only 3.1 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans 25 and older in 2003 had graduate school degrees, compared to 4.7 percent in Puerto Rico in 2000. This rate was lower than that of whites (8.7 percent), blacks (4.1 percent) and Asians (15.6 percent). Among Latinos, Stateside Puerto Ricans fared better than Mexicans (1.4 percent) and Dominicans (1.8 percent), but worse than Cubans (6.7 percent), Central and South Americans (4.2 percent) and other Latinos (5.6 percent).[citation needed]

The University of Puerto Rico is the major Hispanic-serving institution of higher education in the United States that has the capacity, with increased federal government assistance, to open its doors much more aggressively to stateside Puerto Ricans.[citation needed]

Employment

In 2003, 20.7 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans were in professional or managerial occupations, while 33.7 percent had service or sales jobs. The percentage in professional-managerial positions was higher than that of Mexicans (13.2 percent) and Central and South Americans (16.8 percent), but below that of Cubans (28.5 percent), other Latinos (29.0 percent), and non-Latinos (36.2 percent).[citation needed] Between 1993 and 2003, among stateside Puerto Ricans, those in professional-managerial occupations grew from 15.3 to 20.7 percent. While significant, this increase lagged behind that of non-Latinos (+8.8 points) and Cubans (+9.9 points). [citation needed]

Poverty

Stateside Puerto Ricans have been associated with problems faced by communities with persistently high poverty levels. Some have characterized them as part of the urban underclass in the United States.[39] Their poverty rate was only exceeded by that of Dominicans (29.9 percent).[when?] It was higher than every other major group: whites (6.3 percent), blacks (21.3 percent), Asians (7.1 percent), Mexicans (21.2 percent), Cubans (12.9 percent), Central and South Americans (14.1 percent) and other Latinos (13.2 percent). What is troubling about these statistics is that among Latino groups, Puerto Ricans are the only ones who are already US citizens, which should be an advantage, but apparently is not.[40] However, over three quarters were above the poverty line. This rate was about half the poverty rate of Puerto Rico in 2000 of 85.6 percent.[41]

The stateside Puerto Rican poverty rate for families headed by single women was especially alarming, standing at 39.3 percent, although it was significantly lower than the 61.3 percent corresponding poverty rate in Puerto Rico. As with general family poverty, the stateside Puerto Rican poverty level for single female headed households was higher than every other major group except Dominicans (49.0 percent). The rate was 20.3 percent for whites, 35.3 percent for blacks, 14.7 percent far Asians, 37.6 percent for Mexicans, 15.3 percent for Cubans, 27.1 percent for Central and South Americans, and 24.8 percent for other Latinos.

Civic participation

The Puerto Rican community has organized itself to represent its interests in stateside political institutions for close to a century.[42] In New York City, Puerto Ricans first began running for public office in the 1920s. In 1937, they elected their first government representative, Oscar Garcia Rivera, to the New York State Assembly.[43] In Massachusetts, Puerto-Rican Nelson Merced became the first Hispanic elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, and the first Hispanic to hold statewide office in the commonwealth.[44] There are four Puerto Rican members of the United States House of Representatives, Democrats Luis Gutierrez of Illinois, José Enrique Serrano of New York, and Nydia Velázquez of New York, and Republican Raúl Labrador of Idaho, complementing the one Resident Commissioner elected to that body from Puerto Rico. Puerto Ricans have also been elected mayor of major cities such as Miami, Hartford, and Camden.

There are various ways in which stateside Puerto Ricans have exercised their influence. These include protests, campaign contributions and lobbying, and voting. The level of voter participation in Puerto Rico is legendary, greatly exceeding that of the United States.[citation needed] However, many see a paradox in that this high level of voting is not echoed stateside.[45] There, Puerto Ricans have had persistently low voter registration and turnout rates, despite the relative success they have had in electing their own to significant public offices throughout the United States.

To address this problem, the government of Puerto Rico has, since the late 1980s, launched two major voter registration campaigns to increase the level of stateside Puerto Rican voter participation. While Puerto Ricans have traditionally been concentrated in the Northeast, coordinated Latino voter registration organizations, such as the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project and the United States Hispanic Leadership Institute (based in the Midwest), have not concentrated in this region and have focused on the Mexican-American voter. The government of Puerto Rico has sought to fill this vacuum to insure that stateside Puerto Rican interests are well represented in the electoral process, recognizing that the increased political influence of stateside Puerto Ricans also benefits the island.

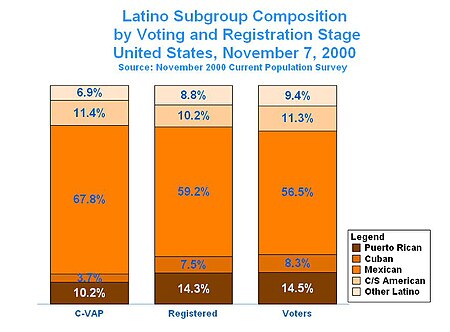

The Census Bureau estimated that 861,728 stateside Puerto Ricans cast their votes in the November 7, 2000 presidential elections. They represented only 0.8 percent of the total, but made up a significant 14.5 percent of the increasingly visible Latino vote. The 5.9 million Latinos who voted in 2000 made up 5.4 percent of total US voters, with higher percentages in politically important areas such as Florida, California, Texas, New York and New Mexico.

While for other Latino groups citizenship status is a major obstacle to voting, this is not a significant issue for stateside Puerto Ricans (99.7 percent of whom are US citizens). One result of this is that although stateside Puerto Ricans made up 10.2 percent of all Latinos of voting age who are citizens, they constituted a significantly higher 14.5 percent of Latinos who actually voted.

In 2000, only 38.6 percent of voting age stateside Puerto Ricans who were citizens were registered to vote. Of the racial-ethnic groups that exceeded this figure, Cubans led the way with 55.9 percent, followed by whites at 54.7 percent, and blacks at 44.6 percent. Among Latinos, the stateside Puerto Rican rate was higher than that of Mexicans (24.0 percent), Central and South Americans (24.7 percent), and other Latinos (34.8 percent).

In terms of actual voter turnout as a percent of those registered, 79.8 percent of stateside Puerto Ricans voted in 2000, lower than whites (86.4 percent) and blacks (84.1 percent). Among Latinos, stateside Puerto Rican turnout was lower than that of Cubans (87.2 percent), Central and South Americans (87.3 percent), and other Latinos (83.8 percent), but was higher than that of Mexicans (75.0 percent).

To get a better picture of the small proportion of voters among all those eligible to vote (whether registered or not), the turnout rate can be calculated as the number of voters as a percentage of the citizen voting age population (C-VAP) for each group. Using this measure, the C-VAP turnout rate for stateside Puerto Ricans was 30.8 percent in 2000. In other words, more than two-thirds of those eligible to vote (1.9 million in actual numbers) did not do so in 2000.

This low level of electoral participation is in sharp contrast with voting levels in Puerto Rico, which are much higher than that not only of this community, but also the United States as a whole.[46] In the 2000 gubernatorial election in Puerto Rico, 90.1 percent of the voting age population was registered to vote, and the voter turnout was 82.6 percent of those registered and 74.4 percent of the total voting age population. In contrast, in the US presidential elections that same year, only 49.5 percent of eligible Americans were registered to vote and only 42.3 percent of these actually cast their ballots (and these are high estimates based on respondents’ recall, while the figures from Puerto Rico are based on actual returns).

The reasons for the differences in Puerto Rican voter participation have been an object of much discussion, but relatively little scholarly research.[47] Explanations have ranged from the structural/institutional, the role of political parties, and political culture, to a combination of these, and other explanations. However, relatively little has been done by US scholars and policymakers to explore this conundrum.

When the relationship of various factors to the turnout rates of stateside Puerto Ricans in 2000 is examined, socioeconomic status emerges as a clear factor.[48] For example, according to the Census:

- Income: the turnout rate for those with incomes less than $10,000 was 37.7 percent, while for those earning $75,000 and above, it was 76.7 percent.

- Employment: 36.5 percent of the unemployed voted, versus 51.2 percent for the employed. The rate for those outside of the labor force was 50.6 percent, probably reflecting the disproportionate role of the elderly, who generally have higher turnout rates.

- Union membership: for union members it was 51.3 percent, while for nonunion members it was 42.6 percent.

- Housing: for homeowners it was 64.0 percent, while it was 41.8 percent for renters.

There were a number of other socio-demographic characteristics where turnout differences also existed, such as:

- Age: the average age of voters was 45.3 years, compared to 38.5 years for eligible nonvoters.

- Education: those without a high school diploma had a turnout rate of 42.5 percent, while for those with a graduate degree, it was 81.0 percent.

- Birthplace: for those born stateside it was 48.9 percent, compared to 52.0 percent for those born in Puerto Rico.

- Marriage status: for those who were married it was 62.0 percent, while those who were never married managed 33.0 percent.

- Military service: for those who ever served in the US military, the turnout rate was 72.1 percent, compared to 48.6 percent for those who never served.

A number of other characteristics, among them gender and race, did not appear to make a significant difference.

Attention has been given to electoral reforms in the last decade or so to create conditions that would make voting and registration easier. These include such things as: the federal "Motor Voter" law that allows registration in government offices while applying for a driver’s license, food stamps or other government service; more flexible absentee ballot procedures; bilingual ballot provisions; same day registration; and so on.

Stateside Puerto Ricans registered to vote in 2000 in a variety of ways and places. The largest group registered through the mail (30.8 percent), followed by those who filled out a form at a voter registration drive (22.1 percent). The other ways they registered were: same day registration at the polling place (14.4 percent); government registration offices (13.7 percent); public assistance agencies (8.4 percent); and schools, hospitals and on campuses (3.0 percent).

Looking at the turnout rates for stateside Puerto Ricans depending on how they registered, they were lowest for registration in government offices and highest in other settings. The highest turnout rates were for those who registered at registration drives (95.2 percent), through the mail (93.8 percent) and those who registered the same day at the polls (90.5 percent). It was lowest for those who registered at government registration offices (70.9 percent) and public assistance agencies (52.7 percent). These figures indicate that a reform like the "Motor Voter" law is having the least effect for stateside Puerto Ricans, while the techniques being pursued by the government of Puerto Rico (registration drives and direct mail) appear more promising. However, much more analysis and fieldwork will be required to come to more definite conclusions.

See also

- Teatro Puerto Rico

- Young Lords

- Puerto Rican people

- List of Puerto Ricans

- History of Puerto Rico

- Demographics of Puerto Rico

- List of Stateside Puerto Ricans

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (November 2009) |

Footnotes

- ^ CBS News: "Romney supports Puerto Rican statehood without English condition" By Sarah B. Boxer March 16, 2012 //, Romney said, "I will support the people of Puerto Rico if they make a decision that they would prefer to become a state; that's a decision that I will support. I don't have preconditions that I would impose."

- ^ New York Times: "In Visit to Puerto Rico, Obama Offers (and Seeks Out) Support" By HELENE COOPER June 14, 2011

- ^ Washington Post: "In Puerto Rico, Romney and statehood inextricably linked" by Philip Rucker March 17, 2012

- ^ DeSipio and Pantoja 2004; Duany 2002; Hernández 1997; Pérez y González 2000; Sánchez González 2001; Torres and Velázquz 1995

- ^ Falcón in Jennings and Rivera 1984: 15-42

- ^ a b Nieto 2000

- ^ Pantoja 2002: 93-108

- ^ Duany 2002: Ch. 7

- ^ Chenault 1938: 72

- ^ Lapp 1990

- ^ Rodríguez, Clara E. "Puerto Ricans: Immigrants and Migrants" (PDF). People of America Foundation. Retrieved 20 August 2011.

- ^ Padilla, Elena. 1992. Up From Puerto Rico. New York: Columbia University Press.

- ^ Dávila, Arlene (2004). Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- ^ "Cleveland city, Ohio: ACS Demographic and Housing Estimates: 2006–2008". Factfinder.census.gov. Retrieved July 8, 2010.

- ^ Cayo-Sexton, Patricia. 1965. Spanish Harlem: An Anatomy of Poverty. New York: Harper and Row

- ^ Bourgois, Philippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003

- ^ Salas, Leonardo. "From San Juan to New York: The History of the Puerto Rican". America: History and Life. 31 (1990)

- ^ Mencher, Joan. 1989. Growing Up in Eastville, a Barrio of New York. New York: Columbia University Press

- ^ How Puerto rico Became White

- ^ a b c d e f g "2010 Census". Medgar Evers College. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ "Puerto Rico Materials2" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ US Census Bureau: Table QT-P10 Hispanic or Latino by Type: 2010 retrieved January 22, 2012 - select state from drop-down menu

- ^ a b c http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_QTP10&prodType=table

- ^ "Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs". USA Today. September 16, 2008.

- ^ "Puerto Rico's population exodus is all about jobs". USA Today. September 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

2000 Censuswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Rivera-Batz and Santiago 1996; Christienson 2003

- ^ a b Falcón in Falcón, Haslip-Viera and Matos-Rodríguez 2004: Ch. 6

- ^ Rivera-Batz and Santiago 1996: 131-135; Maldonado 1997 :Ch. 13; Briggs 2002: Ch. 6

- ^ Duany 2002: Ch. 9

- ^ Nathan 2004

- ^ Baker 2002: Ch. 7 and Appendix 2

- ^ Shaw 1997: 551

- ^ De Genova and Ramos-Zayas 2003

- ^ Baker 2002

- ^ Rivera-Batiz and Santiago 1996

- ^ Senior and Watkins in Cordasco and Bucchioni 1975: 162-163

- ^ DeSipio, et al. 2003

- ^ Rodríguez 1989

- ^ Baker 2002: 132, 133, 154, 167, 169, 171 and 172; Rivera Ramos 2001: 3-5, 162-63

- ^ PRLDEF Latino Data Center 2004

- ^ Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños 2003; Jennings and Rivera 1984

- ^ Falcón in Jennings and Rivera 1984: Ch. 2

- ^ Susan Diesenhouse (21 November 1988). "From Migrant to State House in Massachusetts". The New York Times.

- ^ Falcón in Heine 1983: Ch. 2; Camara-Fuertes 2004

- ^ Camara-Fuertes 2004

- ^ Falcón in Heine 1983: Ch. 2

- ^ Vargas-Ramos examines this relationship for Puerto Ricans in New York City in Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños 2003: 41-71

Bibliography

- Acosta-Belén, Edna, et al. (2000). “Adíos, Borinquen Querida”: The Puerto Rican Diaspora, Its History, and Contributions (Albany, NY: Center for Latino, Latin American and Caribbean Studies, State University of New York at Albany).

- Acosta-Belén, Edna, and Carlos E. Santiago (eds.) (2006). Puerto Ricans in the United States: A Contemporary Portrait (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers).

- Baker, Susan S. (2002). Understanding Mainland Puerto Rican Poverty (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Bell, Christopher (2003). Images of America: East Harlem (Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia).

- Bendixen & Associates (2002). Baseline Study on Mainland Puerto Rican Attitudes Toward Civic Involvement and Voting (Report prepared for the Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration, March–May).

- Bourgois, Philippe. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2003

- Braschi, Giannina (1994). Empire of Dreams. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Braschi, Giannina (1998). Yo-Yo Boing! Pittsburgh: Latin American Literary Review Press.

- Briggs, Laura (2002). Reproducing Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Camara-Fuertes, Luis Raúl (2004). The Phenomenon of Puerto Rican Voting (Gainesville: University Press of Florida).

- Cayo-Sexton, Patricia. 1965. Spanish Harlem: An Anatomy of Poverty. New York: Harper and Row

- Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños (2003), Special Issue: “Puerto Rican Politics in the United States,” Centro Journal, Vol. XV, No. 1 (Spring).

- Census Bureau (2001). The Hispanic Population (Census 2000 Brief) (Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census, May).

- Census Bureau (2003). 2003 Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement Current Population Survey, prepared by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Census Bureau (2004a). Global Population Profile: 2002 (Washington, D.C.: International Programs Center [IPC], Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census) (PASA HRN-P-00-97-00016-00).

- Census Bureau (2004b). Ancestry: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief) (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Chenault, Lawrence R. (1938). The Puerto Rican Migrant in New York City: A Study of Anomie (New York: Columbia University Press).

- Constantine, Consuela. “Political Economy of Puerto Rico, New York.” The Economist. 28 (1992).

- Cortés, Carlos (ed.)(1980). Regional Perspectives on the Puerto Rican Experience (New York: Arno Press).

- Cruz Báez, Ángel David, and Thomas D. Boswell (1997). Atlas Puerto Rico (Miami: Cuban American National Council).

- Christenson, Matthew (2003). “Evaluating Components of International Migration: Migration Between Puerto Rico and the United States” (Working Paper #64, Population Division, U.S. Bureau of the Census).

- Cordasco, Francesco and Eugene Bucchioni (1975). The Puerto Rican Experience: A Sociological Sourcebook (Totowa, NJ: Littlefied, Adams & Co.).

- Dávila, Arlene (2004). Barrio Dreams: Puerto Ricans, Latinos, and the Neoliberal City (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- De Genova, Nicholas and Ana Y. Ramos-Zayas (2003). Latino Crossings: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and the Politics of Race and Citizenship (New York: Routledge).

- de la Garza, Rodolfo O., and Louis DeSipio (eds) (2004). Muted Voices: Latinos and the 2000 Elections (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.).

- DeSipio, Louis, and Adrian D. Pantoja (2004). “Puerto Rican Exceptionalism? A Comparative Analysis of Puerto Rican, Mexican, Salvadoran and Dominican Transnational Civic and Political Ties” (Paper delivered at The Project for Equity Representation and Governance Conference entitled “Latino Politics: The State of the Discipline,” Bush Presidential Conference Center, Texas A&M University in College Station, TX, April 30-May 1, 2004)

- DeSipio, Louis, Harry Pachon, Rodolfo de la Garza, and Jongho Lee (2003). Immigrant Politics at Home and Abroad: How Latino Immigrants Engage the Politics of Their Home Communities and the United States (Los Angeles: Tomás Rivera Policy Institute)

- Duany, Jorge (2002). The Puerto Rican Nation on the Move: Identities on the Island and in the United States (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press).

- Falcón, Angelo (2004). Atlas of Stateside Puerto Ricans (Washington, DC: Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration).

- Puerto Ricans: Thirty Years of Progress & Struggle, Puerto Rican Heritage Month 2006 Calendar Journal (New York: Comite Noviembre). (2006).

- Fears, Darry (2004). "Political Map in Florida Is Changing: Puerto Ricans Affect Latino Vote," Washington Post (Sunday, July 11, 2004): A1.

- Fitzpatrick, Joseph P. (1996). The Stranger Is Our Own: Reflections on the Journey of Puerto Rican Migrants (Kansas City: Sheed & Ward).

- Gottmann, Jean (1957). “Megalopolis or the Urbanization of the Northeastern Seaboard,” Economic Geography, Vol. 33, No. 3 (July): 189-200.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón (2003). Colonial Subjects: Puerto Ricans in a Global Perspective (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Haslip-Viera, Gabriel, Angelo Falcón, and Felix Matos-Rodríguez (eds) (2004). Boricuas in Gotham: Puerto Ricans in the Making of Modern New York City, 1945-2000 (Princeton: Marcus Weiner Publishers).

- Heine, Jorge (ed.) (1983). Time for Decision: The United States and Puerto Rico (Lanham, MD: The North-South Publishing Co.).

- Hernández, Carmen Dolores (1997). Puerto Rican Voices in English: Interviews with Writers (Westport, CT: Praeger).

- Jennings, James, and Monte Rivera (eds) (1984). Puerto Rican Politics in Urban America (Westport: Greenwood Press).

- Lapp, Michael (1990). Managing Migration: The Migration Division of Puerto Rico and Puerto Ricans in New York City, 1948-1968 (Doctoral Dissertation: Johns Hopkins University).

- Maldonado, A.W. (1997). Teodoro Moscoso and Puerto Rico’s Operation Bootstrap (Gainesville: University Press of Florida).

- Mencher, Joan. 1989. Growing Up in Eastville, a Barrio of New York. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Meyer, Gerald. (1989). Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician 1902-1954 (Albany: State University of New York Press).

- Mills, C. Wright, Clarence Senior, and Rose Kohn Goldsen (1950). The Puerto Rican Journey: New York's Newest Migrants (New York: Harper & Brothers).

- Moreno Vega, Marta (2004). When the Spirits Dance Mambo: Growing Up Nuyorican in El Barrio (New York: Three Rivers Press).

- Nathan, Debbie (2004). “Adios, Nueva York,” City Limits (September/October 2004).

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances (2004). Boricua Pop: Puerto Ricans and the Latinization of American Culture (New York: New York University Press).

- Negrón-Muntaner, Frances and Ramón Grosfoguel (eds) (1997). Puerto Rican Jam: Essays on Culture and Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press).

- Nieto, Sonia (ed.) (2000). Puerto Rican Students in U.S. Schools (Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates).

- Padilla, Elena. 1992. Up From Puerto Rico. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Pérez, Gina M. (2004). The Near Northwest Side Story: Migration, Displacement, & Puerto Rican Families (Berkeley: University of California Press).

- Pérez y González, María (2000). Puerto Ricans in the United States (Westport: Greenwood Press).

- Ramos-Zayas, Ana Y. (2003). National Performances: The Politics of Class, Race, and Space in Puerto Rican Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

- Ribes Tovar, Federico (1970). Handbook of the Puerto Rican Community (New York: Plus Ultra Educational Publishers).

- Rivera Ramos. Efrén (2001). The Legal Construction of Identity: The Judicial and Social Legacy of American Colonialism in Puerto Rico (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association).

- Rivera-Batiz, Francisco L., and Carlos E. Santiago (1996). Island Paradox: Puerto Rico in the 1990s (New York: Russell Sage Foundation).

- Rodriguez, Clara E. (1989). Puerto Ricans: Born in the U.S.A. (Boston: Unwin Hyman).

- Rodríguez, Clara E. (2000). Changing Race: Latinos, the Census, and the History of Ethnicity in the United States (New York: New York University Press).

- Rodríguez, Victor M. (2005). Latino Politics in the United States: Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in the Mexican American and Puerto Rican Experience (Dubuque, IW: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company) (Includes a CD)

- Safa, Helen. "The Urban Poor of Puerto Rico: A Study in Development and Inequality". Anthropology Today 24 (1990): 12-91.

- Salas, Leonardo. "From San Juan to New York: The History of the Puerto Rican". America: History and Life. 31 (1990).

- Sánchez González, Lisa (2001). Boricua Literature: A Literary History of the Puerto Rican Diaspora (New York: New York University Press).

- Shaw, Wendy (1997). “The Spatial Concentration of Affluence in the United States,” The Geographical Review 87 (October): 546-553.

- Torres, Andres. (1995). Between Melting Pot and Mosaic: African Americans and Puerto Ricans in the New York Political Economy (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Torres, Andrés and José E. Velázquez (eds) (1998). The Puerto Rican Movement: Voices from the Diaspora (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Vargas and Vatajs -Ramos, Carlos. (2006). Settlement Patterns and Residential Segregation of Puerto Ricans in the United States, Policy Report, Vol. 1, No. 2 (New York: Centro de Estudios Puertorriqueños, Hunter College, Fall).

- Wakefield, Dan. Island in the City: The World of Spanish Harlem. New York: Houghton Mifflin. 1971. Ch. 2. pp. 42–60.

- Whalen, Carmen Teresa (2001). From Puerto Rico to Philadelphia: Puerto Rican Workers and Postwar Economics (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).

- Whalen, Carmen Teresa, and Víctor Vázquez-Hernández (eds.) (2006). The Puerto Rican Diaspora: Historical Perspectives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press).