65th Academy Awards

| 65th Academy Awards | |

|---|---|

Official poster | |

| Date | March 29, 1993 |

| Site | Dorothy Chandler Pavilion Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Hosted by | Billy Crystal |

| Produced by | Gil Cates |

| Directed by | Jeff Margolis |

| Highlights | |

| Best Picture | Unforgiven |

| Most awards | Unforgiven (4) |

| Most nominations | Howards End and Unforgiven (9) |

| TV in the United States | |

| Network | ABC |

| Duration | 3 hours, 33 minutes[1] |

| Ratings | 45.7 million 31.2% (Nielsen ratings) |

The 65th Academy Awards ceremony, presented by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), honored films released in 1992 in the United States and took place on March 29, 1993, at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles beginning at 6:00 p.m. PST / 9:00 p.m. EST. During the ceremony, AMPAS presented Academy Awards (commonly referred to as Oscars) in 23 categories. The ceremony, televised in the United States by ABC, was produced by Gil Cates and directed by Jeff Margolis.[2][3] Actor Billy Crystal hosted the show for the fourth consecutive year.[4] In related events, during a ceremony held at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles on March 6, the Academy Awards for Technical Achievement were presented by host Sharon Stone.[5]

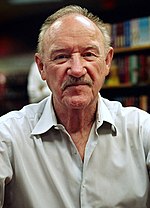

Unforgiven won four Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director for Clint Eastwood, and Best Supporting Actor for Gene Hackman. Al Pacino and Emma Thompson won lead acting honors for Scent of a Woman and Howards End, respectively. Marisa Tomei won Best Supporting Actress for My Cousin Vinny.[6] The telecast garnered 45.7 million viewers in the United States.[7]

Winners and nominees

The nominees for the 65th Academy Awards were announced on February 17, 1993, at the Samuel Goldwyn Theater in Beverly Hills, California, by Robert Rehme, president of the Academy, and actress Mercedes Ruehl.[8] Howards End and Unforgiven led all nominees with nine nominations each.[9]

The winners were announced during the awards ceremony on March 29, 1993. Best Director winner Clint Eastwood became the seventh person nominated for lead acting and directing for the same film.[10] Best Actor winner Al Pacino was the sixth performer to receive nominations in the lead and supporting categories in the same year.[11] He also became the first person to win in the lead acting category after achieving the aforementioned feat.[12] By virtue of his second straight win in both music categories, Alan Menken became the third person to win two Oscars in two consecutive years.[13]

Awards

Winners are listed first, highlighted in boldface, and indicated with a double dagger (‡).[14]

- Academy Honorary Award

- Federico Fellini — In recognition of his place as one of the screen's master storytellers.[15]

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Awards

The award recognizes individuals whose humanitarian efforts have brought credit to the motion picture industry.[16]

Films with multiple nominations and awards

|

|

Presenters and performers

The following individuals (in order of appearance) presented awards or performed musical numbers:[18]

Presenters

Performers

| Name(s) | Role | Performed |

|---|---|---|

| Bill Conti | Musical arranger | Orchestral |

| Billy Crystal | Performer | Opening number: Scent of a Woman (to the tune of "I'm a Woman" by Peggy Lee), Howard's End (to the tune of "Hooray for Hollywood" from Hollywood Hotel), A Few Good Men (to the tune of "Sound Off!"), The Crying Game (to the tune of "(Love Is) The Tender Trap" from The Tender Trap) and Unforgiven to the tune of ("Unforgettable" by Nat King Cole)[19] |

| Brad Kane Lea Salonga |

Performers | "A Whole New World" from Aladdin |

| Plácido Domingo Sheila E. |

Performers | "Beautiful Maria of My Soul" from The Mambo Kings |

| Natalie Cole | Performer | "I Have Nothing" from The Bodyguard and "Run to You" from The Bodyguard |

| Liza Minnelli | Performer | "Ladies' Day" during the musical tribute to women in the film |

| Nell Carter | Performer | "Friend Like Me" from Aladdin |

Ceremony information

After the success of the previous year's ceremony which won several Emmys and critical acclaim, the Academy rehired producer Gil Cates for the fourth consecutive year.[20] In February 1993, actor and comedian Billy Crystal was chosen by Cates as host also for the fourth straight time.[21] Cates justified the decision to hire him saying, "He is a major movie star with a talent for moving the evening's entertainment along."[22] According to an article by Army Archerd published in Variety, Crystal initially declined to host again citing his busy film schedule that included Mr. Saturday Night and City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly's Gold.[23] However, after Cates sent him a funeral wreath with a poem declaring "The show and I are dead without you" followed by a head of a fake dead horse similar to one featured in the film The Godfather, Crystal accepted the role as emcee.[24]

As with previous ceremonies he produced, Cates centered the show around a theme. Inspired by the Year of the Woman in which a record four women were elected to the United States Senate, Cates christened the 1993 show with the theme "Oscar Celebrates Women and the Movies".[25] In tandem with the theme, AMPAS gathered 67 female Oscar winners of every category for a photo that was later shown at the start of the telecast.[26] Actress and singer Liza Minnelli performed "Ladies' Day", a song written by Fred Ebb and John Kander specifically for the broadcast.[27] Oscar-winning documentarian Lynne Littman assembled a montage highlighting women in film.[28]

There was a minor controversy when Snow White (Disney character) was presenting an award for Best Animated Short Subject. She was voiced by Mary Kay Bergman, Adriana Caselotti, the original voice of Snow White was not aware of this. She was reportedly offended that Disney didn't ask her to voice Snow White during the ceremony.[29]

Several other people participated in the production of the ceremony. Bill Conti served as conductor and musical supervisor for the ceremony.[30] Choreographer Debbie Allen supervised the Best Song nominee performances and the "Ladies' Night" musical number.[31] Voice actress Randy Thomas served as announcer of the telecast becoming the first woman to do so.[32]

Box office performance of nominees

| Film | Pre-nomination (Before Feb. 17) |

Post-nomination (Feb. 17-Mar. 29) |

Post-awards (After Mar. 29) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Crying Game | $120 million | $14.3 million | $7.0 million | $141.3 million |

| A Few Good Men | $26.6 million | $11.2 million | $4.6 million | $42.3 million |

| Howard's End | $24.4 million | $942,668 | $36,767 | $25.3 million |

| Scent of a Woman | $34.1 million | $18.5 million | $10.5 million | $63.1 million |

| Unforgiven | $75.3 million | $7.6 million | $18.3 million | $102 million |

At the time of the nominations announcement on February 17, the combined gross of the five Best Picture nominees at the US box office was $252 million, with an average of $50.4 million per film.[33] A Few Good Men was the highest earner among the Best Picture nominees with $120 million in domestic box office receipts. The film was followed by Unforgiven ($75.2 million), Scent of a Woman ($34.1 million), The Crying Game ($14 million), and finally Howards End ($8.7 million).[33]

Of the top 50 grossing movies of the year, 38 nominations went to 13 films on the list. Only A Few Good Men (6th), Unforgiven (17th), Malcolm X (30th) and Scent of a Woman (38th) were nominated for directing, acting, screenwriting, or Best Picture.[34] The other top 50 box office hits that earned nominations were Aladdin (1st), Batman Returns (3rd), Basic Instinct (8th), The Bodyguard (9th), Under Siege (12th), Bram Stoker's Dracula (14th), The Last of the Mohicans (16th), Death Becomes Her (22nd), and Alien³ (26th).[34]

Critical reviews and ratings

The show received a negative reception from most media publications. Associated Press television critic Frazier Moore lamented that Crystal "seemed incredibly listless." He also questioned the purpose of the "Year of the Woman" theme writing, "The Oscar show itself seemed at odds with its own feminist theme."[35] Robert Bianco from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette derided Allen's musical production numbers, comparing them to the disastrous opening number at the 61st ceremony held in 1989.[36] Columnist Matt Roush of USA Today complained, "Crystal, in a by-now-familiar performance, has, in four years, taken a plum assignment and, by repetition, reduced it to shtick." He also wrote that, "The song medley is getting old hat," and the "smug references to his flop Mr. Saturday Night were out of an improv amateur night."[37]

The telecast also received unfavorable reaction from various public feminist figures. In an interview with Los Angeles Daily News author and activist Betty Friedan condemned the "Year of the Woman" theme commenting, "It had no basis in reality. On behalf of women directors, cinematographer, and producers, I resent the travesty of calling that a tribute."[38] Likewise, President of the National Organization for Women's Los Angeles chapter Tammy Bruce chastised ceremony's feminist tribute as "one of the most hypocritical, patronizing things I saw in my whole life."[39] In response, Gil Cates responded towards the criticism of the theme stating, "The theme developed and raised consciousness in a way that I think is positive, not only for the individual in general but for individual women specifically."[38] He also quoted an ancient Chinese proverb later made famous by former U.S. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt saying, "It is better to light one candle than to curse the darkness"[40]

Despite the adverse reception, the ABC broadcast drew in an average of 45.7 million people over its length, which was a 3% increase from the previous year's ceremony.[7] The show also drew higher Nielsen ratings compared to the previous ceremony with 31.2% of households watching over a 51 share.[41][42] In addition, it also drew a higher 18–49 demo rating with a 20.1 rating among viewers in that demographic.[43]

See also

- 13th Golden Raspberry Awards

- 35th Grammy Awards

- 45th Primetime Emmy Awards

- 46th British Academy Film Awards

- 47th Tony Awards

- 50th Golden Globe Awards

- List of submissions to the 65th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

Notes

- A^ : The Academy revoked the Best Foreign Language Film nomination of Uruguay's A Place in the World after an investigation that determined the film as an Argentine production and therefore violated the Academy's rules which require that there be "substantial filmmaking input from the country that submits the film."[44]

- B^ : Hepburn died on January 20, 1993, shortly after AMPAS announced the honor.[45] Her son Sean accepted the award at the ceremony on her behalf.[46]

References

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 889

- ^ Marx, Andy (November 11, 1992). "4th Oscarcast for Cates". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Osborne 2013, p. 418

- ^ MacMinn, Aleene (February 10, 1993). "Morning Report: Movies". Los Angeles Times. Austin Beutner. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Past Scientific & Technical Awards Ceremonies". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

- ^ Fox, David J. (March 31, 1993). "'Unforgiven' Top Film; Pacino, Thompson Win : Academy Awards: Eastwood named best director. Oscars for supporting roles go to Hackman and Tomei". Los Angeles Times. Austin Beutner. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Johnson, Greg (March 18, 1999). "Call It the Glamour Bowl". Los Angeles Times. Austin Beutner. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Weinraub, Bernard (February 18, 1993). "3 Films Dominate Nominees In Oscar Contest". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr. Archived from the original on March 12, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Fox, David J. (February 18, 1993). "The 65th Academy Award Nominations: The Declaration of Independents : The nominations: 'Howards End' and 'Unforgiven' get nine apiece, 'The Crying Game' six. Non-studio and maverick filmmakers have a field day". Los Angeles Times. Austin Beutner. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (February 18, 1993). "Oscars Honor Period Pieces But `Player,' `Malcolm X' Passed Over:". Chicago Sun-Times. Tim Knight. p. 37.

- ^ Rea, Steven (February 18, 1993). "In Line For Oscars "Howards End" And Clint Eastwood's "Unforgiven" Got Nine Academy Award Nominations Each. And Makers Of "The Crying Game" May Get The Last Laugh, With Six Shots At The Statuette". The Philadelphia Inquirer. H.F. Gerry Lenfest. Archived from the original on March 6, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 1173

- ^ Osborne 2013, p. 424

- ^ "The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marx, Andy (January 18, 1993). "Acad Award in picture for Fellini". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b MacMinn, Aleene (January 14, 1993). "Morning Report: Movies". Los Angeles Times. Austin Beutner. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Marx, Andy (January 13, 1993). "Hepburn, Taylor get Hersholt". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 877

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 881

- ^ "Cates to Repeat As Oscars Producer". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. November 13, 1992. p. C2.

- ^ Williams, Jeannie (February 5, 1993). "Bily Crystal, back as Mr. Oscar night". USA Today. Gannett Company. p. 2D.

- ^ "'Perfect host' appointed". The Globe and Mail. Phillip Crawley. February 6, 1993. p. C6.

- ^ Williams, Jeannie (February 18, 1993). "Roping Crystal into Oscar duty". USA Today. Gannett Company. p. 2D.

- ^ Archerd, Army (February 16, 1993). "Cates 'convinces' Crystal to m.c. Oscars again". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 872

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 875

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 886

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 880

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0266220/trivia?ref_=tt_trv_trv

- ^ "Oscar watch". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. January 5, 1993. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Oscar Dance Tryouts Sunday". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. February 22, 1993. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 879

- ^ a b c "1992 Academy Award Nominations and Winner for Best Picture". Box Office Mojo (Amazon.com). Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "1992 Domestic Grosses". Box Office Mojo (Amazon.com). Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Moore, Frazier (March 30, 1993). "Billy Crystal's Performance Lame". The Daily Gazette. John DeAugustine. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Bianco, Robert (March 30, 1993). "Crystal Can't Save Disastrous Oscars Show". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. John Robinson Block. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 892

- ^ a b Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 893

- ^ Karlak, Pat; Swertlow, Frank. "Hollywood's Hollow Salute Oscars' 'Year of Woman' Patronizing, Many Say". The Plain Dealer. Advance Publications. p. 3C.

- ^ Osborne 2013, p. 313

- ^ Schwed, Mark (March 30, 1993). "Kudocast's Nielsen ratings highest in 10 years". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Carter, Bill (March 27, 1996). "TV Notes;Oscar Numbers Slip". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr. Archived from the original on November 19, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Academy Awards ratings" (PDF). Television Bureau of Advertising. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2013. Retrieved June 27, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wiley & Bona 1996, p. 873

- ^ Kehr, Dave (January 21, 1993). "Screen Legend Audrey Hepburn, 63". Chicago Tribune. Tony W. Hunter. Archived from the original on May 5, 2014. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rickey, Carrie (March 30, 1993). "In Like Clint Oscar's Tribute Was Fitting, Given That Women Garnered A Surprising Share Of Awards. (for Al Pacino, The Magic Even Trickled Down To The Title "Scent Of A Woman".)". The Philadelphia Inquirer. H.F. Gerry Lenfest. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

Bibliography

- Osborne, Robert (2013). 85 Years of the Oscar: The Complete History of the Academy Awards. New York, United States: Abbeville Publishing Group. ISBN 0-7892-1142-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Wiley, Mason; Bona, Damien (1996). Inside Oscar: The Unofficial History of the Academy Awards (5 ed.). New York, United States: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-40053-4. OCLC 779680732.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Official websites

- Academy Awards Official website

- The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Official website

- Oscar's Channel at YouTube (run by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences)

- Analysis

- Other resources