Rusyn language

| Rusyn | |

|---|---|

| русинськый язык; руски язик rusîns'kyj jazyk; ruski jazik | |

| Ethnicity | Rusyns |

Native speakers | 623,500 (2000–2006)[1] Census population: 70,000. These are numbers from national official bureaus for statistics: Slovakia – 33,482[2] Serbia – 15,626[3] Poland – 10,000[4] Ukraine – 6,725[5] Croatia – 2,337[6] Hungary – 1,113[7] Czech Republic – 777[8] |

| Cyrillic script (Rusyn alphabets) Latin script (Slovakia)[9] | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | rue |

| Glottolog | rusy1239 |

| Linguasphere | 53-AAA-ec < 53-AAA-e (varieties: 53-AAA-eca to 53-AAA-ecc) |

| |

Rusyn (/ˈruːsɪn/;[13] Carpathian Rusyn: русиньскый язык (rusîn'skyj jazyk), русиньска бесїда (rusîn'ska bes'ida); Pannonian Rusyn: руски язик (ruski jazik), руска бешеда (ruska bešeda)),[14] also known in English as Ruthene (UK: /rʊˈθiːn/, US: /ruːˈθiːn/;[15] sometimes Ruthenian), is an East Slavic language spoken by the Rusyns of Eastern Europe.

There are several controversial theories about the nature of Rusyn as a language or dialect. Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian, as well as American and some Polish and Serbian linguists treat it as a distinct language[16] (with its own ISO 639-3 code), whereas other scholars (especially in Ukraine but also Poland, Serbia, and Romania) treat it as a Southwestern dialect of Ukrainian.[17][18]

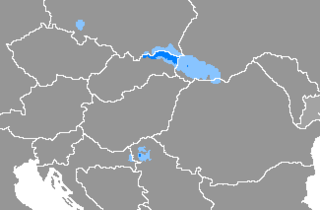

Geographical distribution

Pannonian Rusyn is spoken in Vojvodina in Serbia and in a nearby part of Croatia.

Carpathian Rusyn is spoken in:

- the Transcarpathian Region of Ukraine

- northeastern Slovakia

- Poland (traditionally in the southeast, but now mainly scattered throughout the north and west[19]). The variety of Rusyn spoken in Poland is generally known as Lemko (лемківскій язык lemkivskij jazyk),[20] after the characteristic word лем (lem) meaning "only", "but", and "like"

- Hungary (where the people and language are called ruszin in Hungarian)

- northern Maramureș, Romania, where the people are called Ruteni and the language Ruteană in Romanian

Classification

The classification and identification of the Rusyn language is historically and politically problematic.

Before World War I, Rusyn people were recognized as Ukrainians of Galicia within the Austro-Hungarian Empire; however, in the Hungarian part they were recognized as Rusyns/Ruthenes. Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand had planned to recognize a Rusyn-majority area as one of the states of a planned United States of Greater Austria before his assassination.[citation needed] After the war, the former Austria and Hungary was partitioned, and Carpathian Ruthenia was appended to the new Czechoslovak state as its easternmost province. With the advent of World War II, Carpatho-Ukraine declared its independence, lasting not even one day, until its occupation and annexation by Hungary. After the war, the region was annexed by the Soviet Union as part of the Ukrainian SSR, which proceeded with an anti-ethnic assimilation program. Poland did the same, using internal exile to move all Ukrainians from the southern homelands to western areas incorporated from Germany, and switch everyday language to Polish, and Ukrainian at school.

Scholars with the former Institute of Slavic and Balkan Studies in Moscow (now the Institute of Slavonic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences) formally acknowledged Rusyn as a separate language in 1992, and trained specialists to study the language.[21] These studies were financially supported by the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Ukrainian politicians do not recognise Rusyns as a separate ethnicity, regardless of Rusyn self-identification. Ukraine officially considers Rusyn a dialect of Ukrainian, related to the Hutsul dialect of Ukrainian.

It is not possible to estimate accurately the number of fluent speakers of Rusyn; however, their number is estimated in the tens of thousands.

Serbia has recognized Rusyn, more precisely Pannonian Rusyn, as an official minority language.[22] Since 1995, Rusyn has been recognized as a minority language in Slovakia, enjoying the status of an official language in municipalities where more than 20 percent of the inhabitants speak Rusyn.[23]

Rusyn is listed as a protected language by the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Poland (as Lemko), Serbia and Slovakia.

Grammars and codification

Early grammars include Dmytrij Vyslockij's (Дмитрий Вислоцкий) Карпаторусский букварь (Karpatorusskij bukvar') Vanja Hunjanky (1931),[24] Metodyj Trochanovskij's Буквар. Перша книжечка для народных школ. (Bukvar. Perša knyžečka dlja narodnıx škol.) (1935).,[25][26] and Ivan Harajda (1941).[27] The archaic Harajda's grammar is currently promoted in the Rusyn Wikipedia, although part of the articles are written using other standards (see below).

Currently, there are three codified varieties of Rusyn:

- The Prešov variety in Slovakia (ongoing codification since 1995[28]). A standard grammar was proposed in 1995 by Vasyl Jabur, Anna Plíšková and Kvetoslava Koporová. Its orthography is largely based on Zhelekhivka, a late 19th century variety of the Ukrainian alphabet.

- The Lemko variety in Poland. A standard grammar and dictionary were proposed in 2000 by Mirosława Chomiak and Henryk Fontański.[29]

- The Pannonian Rusyn variety in Serbia and Croatia. It is significantly different from the above two in vocabulary and grammar features. It was first standardized in 1923 by G. Kostelnik. The modern standard has been developed since the 1980s by Julian Ramać, Helena Medješi and Mikhajlo Fejsa (Serbia), and Mihály Káprály (Hungary).

Apart from these codified varieties, there are publications using a mixture of these standards (most notably in Hungary and in Transcarpathian Ukraine), as well as attempts to revitalize the pre-war etymological orthography with old Cyrillic letters (most notably ѣ, or yat'); the latter can be observed in multiple edits in the Rusyn Wikipedia, where various articles represent various codified varieties.

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Velar | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | |||||

| Nasal | m | n | nʲ | |||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | tʲ | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | dʲ | ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡s | t͡sʲ | t͡ʃ | ||||

| voiced | d͡z | d͡zʲ | d͡ʒ | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | sʲ | ʃ | (ʃʲ) | x | h |

| voiced | v | z | zʲ | ʒ | (ʒʲ) | |||

| Rhotic | r | rʲ | ||||||

| Approximant | lateral | l | lʲ | |||||

| central | (w) | j | ||||||

The [w] sound only exists within alteration of [v]. However, in the Lemko variety, the [w] sound also represents the non-palatalized L, as is the case with the Polish ł.

A soft consonant combination sound [ʃʲt͡ʃʲ] exists more among the northern and western dialects. In the eastern dialects the sound is recognized as [ʃʲʃʲ], including the area on which the standard dialect is based. It is noted that a combination sound like this one, could have evolved into a soft fricative sound [ʃʲ].[30]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| ɪ | ɤ | ||

| Mid | ɛ | o | |

| Open | a |

The Carpathian Rusyn alphabets

Each of the three Rusyn standard varieties has its own Cyrillic alphabet. The table below shows the alphabet of Slovakia (Prešov) Rusyn. The alphabet of the other Carpathian Rusyn standard, Lemko (Poland) Rusyn, differs from it only by lacking ё and ї. For the Pannonian Rusyn alphabet, see Pannonian Rusyn language#Writing system.

Romanization (transliteration) is given according to ALA-LC,[31] BGN/PCGN,[32] generic European,[citation needed] ISO/R9 1968 (IDS),[33] and ISO 9.

| Capital | Small | Name | Romanized | Pronunciation | Notes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALA | BGN | Euro | IDS | ISO | |||||

| А | а | a | a | a | a | a | a | /a/ | |

| Б | б | бэ | b | b | b | b | b | /b/ | |

| В | в | вэ | v | v | v | v | v | /v/ | |

| Г | г | гэ | h | h | h | h | h | /ɦ/ | |

| Ґ | ґ | ґэ | g | g | g | g | g | /ɡ/ | |

| Д | д | дэ | d | d | d | d | d | /d/ | |

| Е | е | e | e | e | e | e | e | /ɛ/ | |

| Є | є | є | i͡e | je | je/'e | je | ê | /je, ʲe/ | |

| Ё | ё | ё | ë | jo | jo/'o | ë | /jo/ | not present in Lemko Rusyn or Pannonian Rusyn | |

| Ж | ж | жы | z͡h | ž | ž | ž | ž | /ʒ/ | |

| З | з | зы | z | z | z | z | z | /z/ | |

| І | і | i | i | I | i | I | ì | /i/ | not present in Pannonian Rusyn |

| Ї | ї | ї | ï | ji | ji/'i | ï | ï | /ji/ | not present in Lemko Rusyn |

| И | и | и | i/y | y | î | I | I | /ɪ/ | The Pannonian Rusyn alphabet places this letter directly after з, like the Ukrainian alphabet. According to ALA–LC romanization, it is romanized i for Pannonian Rusyn and y otherwise. |

| Ы | ы | ы | ŷ | y | y | y/ŷ | y | /ɨ/ | not present in Pannonian Rusyn |

| Й | й | йы | ĭ | j | j | j | j | /j/ | |

| К | к | кы | k | k | k | k | k | /k/ | |

| Л | л | лы | l | l | l | l | l | /l/ | |

| М | м | мы | m | m | m | m | m | /m/ | |

| Н | н | ны | n | n | n | n | n | /n/ | |

| О | о | o | o | o | o | o | o | /ɔ/ | |

| П | п | пы | p | p | p | p | p | /p/ | |

| Р | р | ры | r | r | r | r | r | /r/ | |

| С | с | сы | s | s | s | s | s | /s/ | |

| Т | т | ты | t | t | t | t | t | /t/ | |

| У | у | у | u | u | u | u | u | /u/ | |

| Ф | ф | фы | f | f | f | f | f | /f/ | |

| Х | х | хы | k͡h | ch | ch | ch | h | /x/ | |

| Ц | ц | цы | t͡s | c | c | c | c | /t͡s/ | |

| Ч | ч | чы | ch | č | č | č | č | /t͡ʃ/ | |

| Ш | ш | шы | sh | š | š | š | š | /ʃ/ | |

| Щ | щ | щы | shch | šč | šč | šč | ŝ | /ʃt͡ʃ/ | |

| Ю | ю | ю | і͡u | ju | ju/'u | ju | û | /ju/ | |

| Я | я | я | i͡a | ja | ja/'a | ja | â | /ja/ | |

| Ь | ь | мнягкый знак (ірь) | ′ | ’ | ' | ′ | ′ | /ʲ/ | "Soft Sign": marks the preceding consonant as palatalized (soft) |

| Ъ | ъ | твердый знак (ір) | ″ | ’ | " | – | ″ | "Hard Sign": marks the preceding consonant as NOT palatalized (hard). Not present in Pannonian Rusyn | |

In Ukraine, usage is found of the letters о̄ and ӯ.[35][36][37]

Until World War II, the letter ѣ (їть or yat') was used, and was pronounced /ji/ or /i/. This letter is still used in part of the articles in the Rusyn Wikipedia.

Number of letters and relationship to the Ukrainian alphabet

The Prešov Rusyn alphabet of Slovakia has 36 letters. It includes all the letters of the Ukrainian alphabet plus ё, ы, and ъ.

The Lemko Rusyn alphabet of Poland has 34 letters. It includes all the Ukrainian letters with the exception of ї, plus ы and ъ.

The Pannonian Rusyn alphabet has 32 letters, namely all the Ukrainian letters except і.

Alphabetical order

The Rusyn alphabets all place ь after я, as the Ukrainian alphabet did until 1990. The vast majority of Cyrillic alphabets place ь before э (if present), ю, and я.

The Lemko and Prešov Rusyn alphabets place ъ at the very end, while the vast majority of Cyrillic alphabets place it after щ. They also place ы before й, while the vast majority of Cyrillic alphabets place it after ш, щ (if present), and ъ (if present).

In the Prešov Rusyn alphabet, і and ї come before и, and likewise, і comes before и in the Lemko Rusyn alphabet (which doesn't have ї). In the Ukrainian alphabet, however, и precedes і and ї, and the Pannonian Rusyn alphabet (which doesn't have і) follows this precedent by placing и before ї.

Newspapers

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

- Karpatska Rus'

- Русинська бесіда

- Народны новинкы

- Podkarpatská Rus – Подкарпатська Русь ("")

- Amerikansky Russky Viestnik †

- Lemko (Philadelphia, USA) †

- Руснаци у Швеце – Rusnaci u Svece[38]

- Руске слово - [1] (Serbia, Ruski Kerestur)

- Lem.fm - [39] (Poland, Gorlice)

See also

- Besida

- Alexander Duchnovič's Theatre

- Eastern Slovak dialects

- Old Ruthenian

- Pannonian Rusyns

- Rusyns

- Petro Trochanowski, contemporary Rusyn poet

- Metodyj Trochanovskij, Lemko Grammarian

References

- ^ Rusyn at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. "Population and Housing Census 2011: Table 11. Resident population by nationality – 2011, 2001, 1991" (PDF). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ Republic of Serbia, Republic Statistical Office (24 December 2002). "Final results of the census 2002" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Home" (PDF). Central Statistical Office of Poland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ^ State Statistics Committee of Ukraine. "About number and composition population of UKRAINE by data All-Ukrainian population census 2001 data". Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Republic of Croatia – Central Bureau of Statistics". Crostat. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "1.28 Population by mother tongue, nationality and sex, 1900–2001". Hungarian Central Statistical Office. 2001. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ^ "Obyvatelstvo podle věku, mateřského jazyka a pohlaví". Retrieved 2 November 2012.

- ^ Rusyn at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- ^ "Implementation of the Charter in Hungary". Database for the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Public Foundation for European Comparative Minority Research. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ "I Raport dla Sekretarza Rady Europy z realizacji przez Rzeczpospolitą Polską postanowień Europejskiej karty języków regionalnych lub mniejszościowych" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 28 April 2019.

- ^ "The Statue of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, Serbia". Skupstinavojvodine.gov.rs. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "Rusyn, n. and adj. : Oxford English Dictionary".

- ^ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf, p. 8.

- ^ "Ruthene, n. and adj. : Oxford English Dictionary".

- ^ Bernard Comrie, "Slavic Languages," International Encyclopedia of Linguistics (1992, Oxford, Vol 3), pp. 452–456.

Ethnologue, 16th edition - ^ George Y. Shevelov, "Ukrainian," The Slavonic Languages, ed. Bernard Comrie and Greville G. Corbett (1993, Routledge), pp. 947–998.

- ^ Moser M. (2016) Rusyn: A New-Old Language In-between Nations and States // Kamusella T., Nomachi M., Gibson C. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-57703-3

- ^ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf, p. 9.

- ^ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf, p. 8.

- ^ Іван Гвать. "Україна в лещатах російських спецслужб". Radiosvoboda.org. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ "Statute of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina". Skupstinavojvodine.gov.rs. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ^ Slovenskej Republiky, Národná Rada (1999). "Zákon 184/1999 Z. z. o používaní jazykov národnostných menšín" (in Slovak). Zbierka zákonov. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ^ Vyslockyj, Dmytryj (1931). Карпаторусский букварь [Karpatorusskij bukvar'] (in Rusyn). Cleveland.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Trochanovskij, Metodyj (1935). Буквар. Перша книжечка для народных школ. [Bukvar. Perša knyžečka dlja narodnıx škol.] (in Rusyn). Lviv.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bogdan Horbal (2005). Custer, Richard D. (ed.). "The Rusyn Movement among the Galician Lemkos" (PDF). Rusyn-American Almanac of the Carpatho-Rusyn Society (10th Anniversary 2004–2005). Pittsburgh.

- ^ Nadiya Kushko. Literary Standards of the Rusyn Language: The Historical Context and Contemporary Situation. In: The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 51, No. 1 (Spring, 2007), pp. 111-132

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf, p. 52.

- ^ Pugh, Stefan M. (2009). The Rusyn Language. Languages of the World/Materials, 476: München: LINCOM.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Rusyn / Carpatho-Rusyn (ALA-LC Romanization Tables)" (PDF). The Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ^ "Romanization of Rusyn: BGN/PCGN 2016 System" (PDF). NGA GEOnet Names Server. October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ "IDS G: Transliterationstabellen 4. Transliteration der slavischen kyrillischen Alphabete" (PDF). Informationsverbund Deutchschweiz (IDS) (Version 15.10.01 ed.). 2001. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ http://theses.gla.ac.uk/2781/1/2011BaptieMPhil-1.pdf

- ^ Кушницькый, Мигаль (27 May 2020). "Carpatho-Rusyn Phonetics ep3 - О/Ō | Карпаторусинська фонетика №3". YouTube.

- ^ Кушницькый, Мигаль (1 May 2020). "Carpatho-Rusyn phonetics. Ep#2 - і, ї, ӯ | Карпаторусинська фонетика. Другый епізод". YouTube.

- ^ "ruegrammatica". rueportal.eu.

- ^ "Rusnaci u svece". tripod.lycos.com. Retrieved 7 March 2017.

- ^ "Хыжа | lem.fm - Радийо Руской Бурсы". lem.fm - Радийо Руской Бурсы. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

Further reading

- Gregory Zatkovich. The Rusin Question in a Nutshell. OCLC 22065508.

- A new Slavic language is born. The Rusyn literary language in Slovakia. Ed. Paul Robert Magocsi. New York 1996.

- Paul Robert Magocsi. Let's speak Rusyn. Бісідуйме по-руськы. Englewood 1976.

- Aleksandr Dmitrievich Dulichenko. Jugoslavo-Ruthenica. Роботи з рускей филолоґиї. Нови Сад 1995.

- Taras Kuzio, "The Rusyn question in Ukraine: sorting out fact from fiction", Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism, XXXII (2005)

- Elaine Rusinko, "Rusinski/Ruski pisni" selected by Nataliya Dudash; "Muza spid Karpat (Zbornik poezii Rusiniv na Sloven'sku)" assembled by Anna Plishkova. Books review. "The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 42, No. 2. (Summer, 1998), pp. 348-350. JSTOR archive

- Плішкова, Анна [Anna Plishkova] (ed.): Муза спід Карпат (Зборник поезії Русинів на Словеньску). [Muza spid Karpat (Zbornik poezii Rusiniv na Sloven'sku)] Пряшів: Русиньска оброда, 1996. on-line[permanent dead link]

- Геровский Г.Ю. Язык Подкарпатской Руси – Москва, 1995

- Marta Harasowska. "Morphophonemic Variability, Productivity, and Change: The Case of Rusyn", Berlin ; New York : Mouton de Gruyter, 1999, ISBN 3-11-015761-6.

- Book review by Edward J. Vajda, Language, Vol. 76, No. 3. (Sep., 2000), pp. 728–729

- I. I. Pop, Paul Robert Magocsi, Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture, University of Toronto Press, 2002, ISBN 0-8020-3566-3

- Anna Plišková: Rusínsky jazyk na Slovensku: náčrt vývoja a súčasné problémy. Prešov : Metodicko-pedagogické centrum, 2007, 116 s. Slovak Rusyn

External links

- The World Academy of Rusyn Culture

- Rusyn Greco Catholic Church in Novi Sad (Vojvodina-Serbia)

- Rusyn-Ukrainian Dictionary

- Course of Lemko-Rusyn Language (in Polish and Lemko)