King of Kings

| Part of a series on |

| Imperial, royal, noble, gentry and chivalric ranks in West, Central, South Asia and North Africa |

|---|

|

King of Kings[n 1] was a ruling title employed primarily by monarchs based in the Middle East. Though most commonly associated with Iran (historically known as Persia in the West[7]), especially the Achaemenid and Sasanian Empires, the title was originally introduced during the Middle Assyrian Empire by king Tukulti-Ninurta I (reigned 1233–1197 BC) and was subsequently used in a number of different kingdoms and empires, including the aforementioned Persia, various Hellenic kingdoms, Armenia, Georgia, and Ethiopia.

The title is commonly seen as equivalent to that of Emperor, both titles outranking that of king in prestige, stemming from the medieval Byzantine emperors who saw the Shahanshahs of the Sasanian Empire as their equals. The last reigning monarchs to use the title of Shahanshah, those of the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran (1925–1979), also equated the title with "Emperor". The rulers of the Ethiopian Empire used the title of Nəgusä Nägäst (literally "King of Kings"), which was officially translated as "Emperor". The female variant of the title, as used by the Ethiopian Zewditu, was Queen of Kings (Ge'ez: Nəgəstä Nägäst). In the Sasanian Empire, the female variant used was Queen of Queens (Middle Persian: bānbishnān bānbishn).

In Judaism, Melech Malchei HaMelachim ("the King of Kings of Kings") came to be used as a name of God. "King of Kings" (βασιλεὺς τῶν βασιλευόντων) is also used in reference to Jesus Christ several times in the Bible, notably in the First Epistle to Timothy and twice in the Book of Revelation. In Islam, both the terms King of Kings and the Persian variant Shahanshah are condemned, particularly in Sunni hadith.

Historical usage

Ancient India

In Ancient India, Sanskrit language words such as Chakravarti, Rajadhiraja and Maharadhiraja are among the terms that were used for employing the title of the King of Kings.[8][9] These words also occur in Aitareya Aranyaka and other parts of Rigveda (1700 BC - 1100 BC).[10]

Ancient Mesopotamia

Assyria and Babylon

The title King of Kings was first introduced by the Assyrian king Tukulti-Ninurta I (who reigned between 1233 and 1197 BC) as šar šarrāni. The title carried a literal meaning in that a šar was traditionally simply the ruler of a city-state. With the formation of the Middle Assyrian Empire, the Assyrian rulers installed themselves as kings over an already present system of kingship in these city-states, becoming literal "kings of kings".[1] Following Tukulti-Ninurta's reign, the title was occasionally used by monarchs of Assyria and Babylon.[2] Later Assyrian rulers to use šar šarrāni include Esarhaddon (r. 681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal (r. 669–627 BC).[11][12] "King of Kings", as šar šarrāni, was among the many titles of the last Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC).[13]

Boastful titles claiming ownership of various things were common throughout ancient Mesopotamian history. For instance, Ashurbanipal's great-grandfather Sargon II used the full titulature of Great King, Mighty King, King of the Universe, King of Assyria, King of Babylon, King of Sumer and Akkad.[14]

Urartu and Media

The title of King of Kings occasionally appears in inscriptions of kings of Urartu.[2] Although no evidence exists, it is possible that the title was also used by the rulers of the Median Empire, since its rulers borrowed much of their royal symbolism and protocol from Urartu and elsewhere in Mesopotamia. The Achaemenid Persian variant of the title, Xšāyaθiya Xšāyaθiyānām, is Median in form which suggests that the Achaemenids may have taken it from the Medes rather than from the Mesopotamians.[2]

An Assyrian-language inscription on a fortification near the fortress of Tušpa mentions King Sarduri I of Urartu as a builder of a wall and a holder of the title King of Kings;[15]

This is the inscription of king Sarduri, son of the great king Lutipri, the powerful king who does not fear to fight, the amazing shepherd, the king who ruled the rebels. I am Sarduri, son of Lutipri, the king of kings and the king who received the tribute of all the kings. Sarduri, son of Lutipri, says: I brought these stone blocks from the city of Alniunu. I built this wall.

— Sarduri I of Urartu

Iran

Achaemenid usage

The Achaemenid Empire, established in 550 BC after the fall of the Median Empire, rapidly expanded over the course of the sixth century BC. Asia Minor and the Lydian kingdom was conquered in 546 BC, the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, Egypt in 525 BC and the Indus region in 513 BC. The Achaemenids employed satrapal administration, which became a guarantee of success due to its flexibility and the tolerance of the Achaemenid kings for the more-or-less autonomous vassals. The system also had its problems; though some regions became nearly completely autonomous without any fighting (such as Lycia and Cilicia), other regions saw repeated attempts at rebellion and secession.[16] Egypt was a particularly prominent example, frequently rebelling against Achaemenid authority and attempting to crown their own Pharaohs. Though it was eventually defeated, the Great Satraps' Revolt of 366–360 BC showed the growing structural problems within the Empire.[17]

The Achaemenid Kings used a variety of different titles, prominently Great King and King of Countries, but perhaps the most prominent title was that of King of Kings (rendered Xšāyaθiya Xšāyaθiyānām in Old Persian),[2] recorded for every Achaemenid king. The full titulature of the king Darius I was "great king, king of kings, king in Persia, king of the countries, Hystaspes’ son, Arsames’ grandson, an Achaemenid".[18][19] An inscription in the Armenian city of Van by Xerxes I reads;[20]

I am Xerxes, the great king, the king of kings, the king of the provinces with many tongues, the king of this great earth far and near, son of king Darius the Achaemenian.

— Xerxes I of Persia

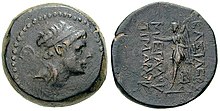

Parthian and Sasanian usage

The standard royal title of the Arsacid (Parthian) kings while in Babylon was Aršaka šarru ("Arsacid king"), King of Kings (recorded as šar šarrāni by contemporary Babylonians)[21] was adopted first by Mithridates I (r. 171–132 BC), though he used it infrequently.[22][23] The title first began being consistently used by Mithridates I's nephew, Mithridates II, who after adopting it in 111 BC used it extensively, even including it in his coinage (as the Greek BAΣIΛEΥΣ BAΣIΛEΩN)[4] until 91 BC.[24] It is possible that Mithridates II's, and his successors', use of the title was not a revival of the old Achaemenid imperial title (since it was not used until almost a decade after Mithridates II's own conquest of Mesopotamia) but actually stemmed from Babylonian scribes who accorded the imperial title of their own ancestors onto the Parthian kings.[25] Regardless of how he came to acquire the title, Mithridates II did undertake conscious steps to be seen as an heir to and restorer of Achaemenid traditions, introducing a crown as the customary headgear on Parthian coins and undertaking several campaigns westwards into former Achaemenid lands.[4]

The title was rendered as šāhān šāh in Middle Persian and Parthian and remained in consistent use until the ruling Arsacids were supplanted by the Sasanian dynasty of Ardashir I, creating the Sasanian Empire. Ardashir himself used a new variant of the title, introducing "Shahanshah of the Iranians" (Middle Persian: šāhān šāh ī ērān). Ardashir's successor Shapur I introduced another variant; "Shahanshah of the Iranians and non-Iranians" (Middle Persian: šāhān šāh ī ērān ud anērān), possibly only assumed after Shapur's victories against the Roman Empire (which resulted in the incorporation of new non-Iranian lands into the empire). This variant, Shahanshah of Iranians and non-Iranians, appear on the coinage of all later Sasanian kings.[3] The final Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire was Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651 AD). His reign ended with the defeat and conquest of Persia by the Rashidun Caliphate, ending the last pre-Islamic Iranian Empire.[26] The defeat of Yazdegerd and the fall of the Sasanian Empire was a blow to the national sentiment of the Iranians, which was slow to recover. Although attempts were made at restoring the Sasanian Empire, even with Chinese help, these attempts failed and the descendants of Yazdegerd faded into obscurity.[27] The title Shahanshah was criticized by later Muslims, associating it with the Zoroastrian faith and referring to it as "impious".[28]

The female variant of the title in the Sasanian Empire, as attested for Shapur I's (r. 240–270 AD) daughter Adur-Anahid, was the matching bānbishnān bānbishn ("Queen of Queens"). The similar title shahr banbishn ("Queen of the empire") is attested for Shapur I's wife Khwarranzem.[29]

Buyid revival

Following the fall of the Sasanian Empire, Iran was ruled by a series of relatively short-lived Muslim Iranian dynasties; including the Samanids and Saffarids. Although Iranian resentment against the Abbasid Caliphs was common, the resentment materialized as religious and political movements combining old Iranian traditions with new Arabic ones rather than as full-scale revolts. The new dynasties do not appear to have had any interest in re-establishing the empire of the old Shahanshahs, they at no point seriously questioned the suzerainty of the Caliphs and actively promoted Arabic culture. Though the Samanids and the Saffarids also actively promoted the revival of the Persian language, the Samanids remained loyal supporters of the Abbasids and the Saffarids, despite at times being in open rebellion, did not revive any of the old Iranian political structures.[30]

The Shi'a Buyid dynasty, of Iranian Daylamite origin, came to power in 934 AD through most of the old Iranian heartland. In contrast to earlier dynasties, ruled by Emirs and wanting to appease the powerful ruling Caliphs, the Buyids consciously revived old symbols and practices of the Sasanian Empire.[31] The region of Daylam had resisted the Caliphate since the fall of the Sasanian Empire, attempts at restoring a native Iranian rule built on Iranian traditions had been many, though unsuccessful. Asfar ibn Shiruya, a Zoroastrian and Iranian nationalist, rebelled against the Samanids in 928 AD, intending to put a crown on himself, set up a throne of gold and make war on the Caliph. More prominently, Mardavij, who founded the Ziyarid Dynasty, was also Zoroastrian and actively aspired to restore the old empire. He was quoted as promising to destroy the empire of the Arabs and restore the Iranian empire and had a crown identical to the one worn by the Sasanian Khosrow I made for himself.[32] At the time he was murdered by his own Turkic troops, Mardavij was planning a campaign towards Baghdad, the Abbasid capital. Subsequent Ziyarid rulers were Muslim and made no similar attempts.[33]

After the death of Mardavij, many of his troops entered into the service of the founder of the Buyid dynasty, Imad al-Dawla.[33] Finally, the Buyid Emir Panāh Khusraw, better known by his laqab (honorific name) of 'Adud al-Dawla proclaimed himself Shahanshah after defeating rebellious relatives and becoming the sole ruler of the Buyid dynasty in 978 AD.[n 2] Those of his successors that likewise exercised full control over all the Buyid emirates would also style themselves as Shahanshah.[34][35]

During times of Buyid infighting, the title became a matter of importance. When a significant portion of Firuz Khusrau's (laqab Jalal al-Dawla) army rebelled in the 1040s and wished to enthrone the other Buyid Emir Abu Kalijar as ruler over the lands of the entire dynasty, they minted coins in his name with one side bearing the name of the ruling Caliph (Al-Qa'im) and the other side bearing the inscription "al-Malik al-Adil Shahanshah".[36] When discussing peace terms, Abu Kalijar in turn addressed Jalal in a letter with the title Shahanshah.[37]

When the struggle between Abu Kalijar and Jalal al-Dawla resumed, Jalal, wanting to assert his superiority over Kalijar, made a formal application to Caliph Al-Qa'im for the usage of the title Shahanshah, the first Buyid ruler to do so. It can be assumed that the Caliph agreed (since the title was later used), but its usage by Jalal in a mosque caused outcry at its impious character.[28] Following this, the matter was raised to a body of jurists assembled by the Caliph. Though some dissented, the body as a whole ruled that the usage of al-Malik al-Adil Shahanshah was lawful.[38]

Hellenic usage

Alexander the Great's conquests ended the Achaemenid Empire and the subsequent division of Alexander's own empire resulted in the Seleucid dynasty inheriting the lands formerly associated with the Achaemenid dynasty. Although Alexander himself did not employ any of the old Persian royal titles, instead using his own new title "King of Asia" (βασιλεὺς τῆς Ἀσίας),[39] the monarchs of the Seleucid Empire more and more aligned themselves to the Persian political system. The official title of most of the Seleucid kings was "Great King", which like "King of Kings", a title of Assyrian origin, was frequently used by the Achaemenid rulers and was intended to demonstrate the supremacy of its holder over other rulers. "Great King" is prominently attested for both Antiochus I (r. 281–261 BC) in the Borsippa Cylinder and for Antiochus III the Great (r. 222–187 BC) throughout his rule.[40]

In the late Seleucid Empire, "King of Kings" even saw a revival, despite the fact that the territory controlled by the Empire was significantly smaller than it had been during the reigns of the early Seleucid kings. The title was evidently quite well known to be associated with the Seleucid king, the usurper Timarchus (active 163–160 BC) called himself "King of Kings" and the title was discussed in sources from outside the empire as well.[41] Some non-Seleucid rulers even assumed the title for themselves, notably in Pontus (especially prominently used under Mithridates VI Eupator).[41][42]

It is possible that the Seleucid usage indicates that the title no longer implied complete vassalization of other kings but instead a recognition of suzerainty (since the Seleucids were rapidly losing the loyalty of their vassals at the time).[41]

Armenia

After the Parthian Empire under Mithridates II defeated Armenia in 105 BC, the heir to the Armenian throne, Tigranes, was taken hostage and kept at the Parthian court until he bought his freedom in 95 BC (by handing over "seventy valleys" in Atropatene) and assumed the Armenian throne.[43] Tigranes ruled, for a short time in the first century BC, the strongest empire in the Middle East which he had built himself. After conquering Syria in 83 BC, Tigranes assumed the title King of Kings.[44] The Armenian kings of the Bagratuni dynasty from the reign of Ashot III 953–977 AD to the dynasty's end in 1064 AD revived the title, rendering it as the Persian Shahanshah.[45]

Georgia

King of Kings was revived in the Kingdom of Georgia by King David IV (r. 1089–1125 AD), rendered as mepet mepe in Georgian. All subsequent Georgian monarchs, such as Tamar the Great, used the title to describe their rule over all Georgian principalities, vassals and tributaries. Their use of the title probably derived from the ancient Persian title.[46][47]

Palmyra

After a successful campaign against the Sasanian Empire in 262 AD, which restored Roman control to territories that had been lost to the Shahanshah Shapur I, the ruler of the city of Palmyra, Odaenathus, founded the Palmyrene kingdom. Though a Roman vassal, Odaenathus assumed the title Mlk Mlk dy Mdnh (King of Kings and Corrector of the East). Odaenathus son, Herodianus (Hairan I) was acclaimed as his co-monarch, also given the title King of Kings.[48][49] Usage of the title was probably justified through proclaiming the Palmyrene kingdom as the legitimate successor state of the Hellenic Seleucid empire, which had controlled roughly the same territories near its end. Herodianus was crowned at Antioch, which had been the final Seleucid capital.[49]

Though the same title was used by Odaenathus second son and successor following the deaths of both Odaenathus and Herodianus, Vaballathus and his mother Zenobia soon relinquished it, instead opting for the Roman Augustus ("Emperor") and Augusta ("Empress") respectively.[50]

Ethiopia

The title King of Kings was used by the rulers of the Aksumite Kingdom since the reign Sembrouthes c. 250 AD.[51] The rulers of the Ethiopian Empire, which existed from 1270 to 1974 AD, also used the title of Nəgusä Nägäst, sometimes translated to "King of the Kingdom", but most often equated to "King of Kings" and officially translated to Emperor. Though the Ethiopian Emperors had been literal "Kings of Kings" for the duration of the Empire's history, with regional lords using the title of Nəgus ("king"), this practice was ended by Haile Selassie (r. 1930–1974 AD), who somewhat paradoxically still retained the use of Nəgusä Nägäst.[6] Empress Zewditu (r. 1916–1930 AD), the only female monarch of the Ethiopian Empire, assumed the variant "Queen of Kings" (Nəgəstä Nägäst).[52][53]

Champa

From the 7th century to 15th century, grand rulers of Chamic-speaking confederation of Champa, which existed from 3rd century AD to 1832 in present day Central Vietnam, employed titles maharajadhiraja (great king of kings) and pu po tana raya (king of kings). The early kings of Champa before decentralization referred themselves by several different titles such as mahārāja (great king), eg. Bhadravarman I (r.380-413), or campāpr̥thivībhuj (lord of the land of Champa) used by Kandarpadharma (r. 629-640).

In religion

Judaism

In Judaism, Melech Malchei HaMelachim ("the King of Kings of Kings") came to be used as a name of God, using the double superlative to put the title one step above the royal title of the Babylonian and Persian kings referred to in the Bible.[54]

Christianity

"King of Kings" (βασιλεὺς τῶν βασιλευόντων) is used in reference to Jesus Christ several times in the Bible, notably once in the First Epistle to Timothy (6:15) and twice in the Book of Revelation (17:14, 19:11–16);[55]

... which He will bring about at the proper time—He who is the blessed and only Sovereign, the King of kings and Lord of lords, ...

— First Epistle to Timothy 6:15

"These will wage war against the Lamb, and the Lamb will overcome them, because He is Lord of lords and King of kings, and those who are with Him are the called and chosen and faithful."

— Book of Revelation 17:14

And I saw heaven opened, and behold, a white horse, and He who sat on it is called Faithful and True, and in righteousness He judges and wages war. His eyes are a flame of fire, and on His head are many diadems; and He has a name written on Him which no one knows except Himself. ... And on His robe and on His thigh He has a name written, "KING OF KINGS, AND LORD OF LORDS."

— Book of Revelation 19:11–12, 16

Some Christian realms (Georgia, Armenia and Ethiopia) employed the title and it was part of the motto of the Byzantine Emperors of the Palaiologan period, Βασιλεὺς Βασιλέων Βασιλεύων Βασιλευόντων (Basileus Basileōn, Basileuōn Basileuontōn, literally "King of Kings, ruling over those who rule").[56] In the Byzantine Empire the word Βασιλεὺς (Basileus), which had meant "king" in ancient times had taken up the meaning of "emperor" instead. Byzantine rulers translated "Basileus" into "Imperator" when using Latin and called other kings rēx or rēgas, hellenized forms of the Latin title rex.[57][58] As such, Βασιλεὺς Βασιλέων in the Byzantine Empire would have meant "Emperor of Emperors". The Byzantine rulers only accorded the title of Basileus onto two foreign rulers they considered to be their equals, the Kings of Axum and the Shahanshahs of the Sasanian Empire, leading to "King of Kings" being equated to the rank of "Emperor" in the view of the West.[59]

Islam

Following the fall of the Sasanian Empire in 651 AD, the title of Shahanshah was sternly criticized in the Muslim world. It was problematic enough that the adoption of Shahanshah by the Muslim Buyid dynasty in Persia required a body of jurists to agree on its lawfulness[38] and the title itself (both as "king of kings" and as the Persian variant Shahanshah) is condemned in Sunni hadith, a prominent example being Sahih al-Bukhari Book 73 Hadiths 224 and 225;[60][61]

Allah's Apostle said, "The most awful name in Allah's sight on the Day of Resurrection, will be (that of) a man calling himself Malik Al-Amlak (the king of kings)."

— Sahih al-Bukhari Book 73 Hadith 224

The Prophet said, "The most awful (meanest) name in Allah's sight." Sufyan said more than once, "The most awful (meanest) name in Allah's sight is (that of) a man calling himself king of kings." Sufyan said, "Somebody else (i.e. other than Abu Az-Zinad, a sub-narrator) says: What is meant by 'The king of kings' is 'Shahan Shah.,"

— Sahih al-Bukhari Book 73 Hadith 225

The condemnation of the title within the Islamic world may stem from that the concept of God alone being king had been prominent in early Islam. Opposing worldly kingship, the use of "King of Kings" was deemed obnoxious and blasphemous.[27]

Modern usage

Iran

After the end of the Buyid dynasty in 1062, the title of Shahanshah was used intermittently by rulers of Iran until the modern era. The title, rendered as Shahinshah, is used on some of the coins of Alp Arslan (r. 1063–1072), the second sultan of the Seljuk Empire.[62]

The title was adopted by Ismail I (r. 1501–1524), the founder of the Safavid dynasty. Upon his capture of Tabriz in 1501, Ismail proclaimed himself the Shāh of Azerbaijan and the Shahanshah of Iran.[63] The term šāhanšāh-e Irān, King of Kings of Iran, is richly attested for the Safavid period and for the preceding Timurid period (when it was not in use).[64] Nader Shah, founder of the later Afsharid Dynasty, assumed the title šāhanšāh in 1739 to emphasize his superiority over Muhammad Shah of the Mughal Empire in India.[65]

The title Shahanshah is also attested for Fath-Ali Shah Qajar of the Qajar dynasty (r. 1797–1834). Fath-Ali's reign was noted for its pomp and elaborate court protocol.[66] An 1813/1814 portrait of Fath-Ali contains a poem with the title; "Is this a portrait of a shahanshah, inhabitant of the skies / Or is it the rising of the sun and the image of the moon?".[67]

The Qajar dynasty was overthrown in 1925, replaced by the Pahlavi dynasty. Both reigning members of this dynasty, Reza Shah Pahlavi (r. 1925–1941) and Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (r. 1941–1979), before they too were overthrown as part of the Iranian revolution in 1979, used the title of Shahanshah.[68] Although Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had reigned as Shah for twenty-six years by then, he only took the title of Shahanshah on 26 October 1967 in a lavish coronation ceremony held in Tehran. He said that he chose to wait until this moment to assume the title because in his own opinion he "did not deserve it" up until then; he is also recorded as saying that there was "no honour in being Emperor of a poor country" (which he viewed Iran as being until that time).[69] The current head of the exiled house of Pahlavi, Reza Pahlavi II, symbolically declared himself Shahanshah at the age of 21 after the death of his father in 1980.[70]

Libya

In 2008, the Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi claimed the title of "King of Kings" after a gathering of more than 200 African tribal kings and chiefs endorsed his use of the title on 28 August that year, stating that "We have decided to recognise our brotherly leader as the 'king of kings, sultans, princes, sheikhs and mayors of Africa". At the meeting, held in the city of Benghazi, Gaddafi was given gifts including a throne, an 18th-century Qur'an, traditional outfits and ostrich eggs. At the same meeting, Gaddafi urged his guests to put pressure on their own governments and speed the process of moving towards a unified African continent. Gaddafi told those that attended the meeting that "We want an African military to defend Africa, we want a single African currency, we want one African passport to travel within Africa".[71][72] The meeting was later referred to as a "bizarre ceremony" in international media.[73]

References

Annotations

- ^ Akkadian: šar šarrāni;[1] Old Persian: Xšāyaθiya Xšāyaθiyānām;[2] Middle Persian: šāhān šāh;[3] Modern Template:Lang-fa; Template:Lang-grc-gre;[4] Template:Lang-hy; Template:Lang-sa; Georgian: მეფეთ მეფე, Mepet mepe;[5] Template:Lang-gez[6]

- ^ Though the title being revived by 'Adud al-Dawla is the most common view, some scant evidence suggests that it may have been assumed by Buyid rulers even earlier, possibly by Dawla's father Rukn al-Dawla or uncle Imad al-Dawla.[30]

Citations

- ^ a b Handy 1994, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e King of kings in Media and Urartu.

- ^ a b Yücel 2017, pp. 331–344.

- ^ a b c Olbrycht 2009, p. 165.

- ^ Pinkerton 1811, p. 124.

- ^ a b Dejene 2007, p. 539.

- ^ Yarshater 1989.

- ^ Pasricha 1998, p. 11. "In Sanskrit, 'Chakravarti' means the King of Kings."

- ^ Atikal & Parthasarathy (tr.) 2004, p. 342.

- ^ Mookerji 1914, p. 71.

- ^ Karlsson 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Karlsson 2017, p. 10.

- ^ Oshima 2017, p. 655.

- ^ Levin 2002, p. 362.

- ^ Tušpa (Van).

- ^ Engels 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Engels 2011, p. 21.

- ^ DARIUS iv. Darius II.

- ^ Achaemenid Dynasty.

- ^ Cartwright 2018.

- ^ Simonetta 1966, p. 18.

- ^ Daryaee 2012, p. 179.

- ^ Schippmann 1986, pp. 525–536.

- ^ Shayegan 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Shayegan 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Kia 2016, pp. 284–285.

- ^ a b Madelung 1969, p. 84.

- ^ a b Amedroz 1905, p. 397.

- ^ Sundermann 1988, pp. 678–679.

- ^ a b Madelung 1969, p. 85.

- ^ Goldschmidt 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Madelung 1969, p. 86.

- ^ a b Madelung 1969, p. 87.

- ^ Clawson & Rubin 2005, p. 19.

- ^ Kabir 1964, p. 240.

- ^ Amedroz 1905, p. 395.

- ^ Amedroz 1905, p. 396.

- ^ a b Amedroz 1905, p. 398.

- ^ Fredricksmeyer 2000, pp. 136–166.

- ^ Engels 2011, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Engels 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Kotansky 1994, p. 181.

- ^ Strabo, Geography.

- ^ Olbrycht 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Greenwood 2011, p. 52.

- ^ Dzagnidze 2018.

- ^ Vashalomidze 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, pp. 149, 176, 178.

- ^ a b Andrade 2013, p. 333.

- ^ Ando 2012, p. 210.

- ^ Kobishchanov 1979, p. 195.

- ^ Kiunguyu 2018.

- ^ Tesfu 2008.

- ^ Gluck 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Jesus As King Of Kings.

- ^ Atlagić 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Kazhdan 1991, p. 264.

- ^ Morrisson 2013, p. 72.

- ^ Chrysos 1978, p. 42.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari Book 73 Hadith 224.

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari Book 73 Hadith 225.

- ^ CNG, 208. Lot:462.

- ^ Lenczowski 1978, p. 79.

- ^ Iranian Identity.

- ^ NĀDER SHAH.

- ^ The Court of Fath 'Ali Shah at the Nowrooz Salaam Ceremony.

- ^ Portrait of Fath Ali Shah Seated.

- ^ Saikal & Schnabel 2003, p. 9.

- ^ National Geographic Magazine, p. 9.

- ^ Goodspeed 2010.

- ^ Gaddafi named 'king of kings'.

- ^ Gaddafi: Africa's 'king of kings'.

- ^ Adebajo 2011.

Bibliography

- Amedroz, H. F. (1905). "The Assumption of the Title Shahanshah by Buwayhid Rulers". The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society. 5: 393–399. JSTOR 42662137.

- Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01205-9.

- Atikal, Ilanko (2004). The Cilappatikāram: The Tale of an Anklet. Translated by Parthasarathy, R. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143031963.

- Atlagić, Marko (1997). "The cross with symbols S as heraldic symbols" (PDF). Baština. 8: 149–158. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-21.

- Chrysos, Evangelos K. (1978). "The Title Βασιλευσ in Early Byzantine International Relations". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 32: 29–75. doi:10.2307/1291418. JSTOR 1291418.

- Clawson, Patrick; Rubin, Michael (2005). Eternal Iran: continuity and chaos. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6276-8.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–432. ISBN 978-0-19-987575-7. Retrieved 2019-02-22.

- Dejene, Solomon (2007). "Exploring Iddir: Toward Developing a Contextual Theology of Ethiopia". Research in Ethiopian Studies: Selected Papers of the 16th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies.

- Engels, David (2011). "Middle Eastern 'Feudalism' and Seleucid Dissolution". In K. Erickson; G. Ramsay (eds.). Seleucid Dissolution. The Sinking of the Anchor. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 19–36. ISBN 978-3447065887. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- Fredricksmeyer, Ernst (2000). Bosworth, A. B.; Baynham, E. J. (eds.). Alexander the Great and the Kingship of Asia. Alexander the Great in Fact and Fiction. Oxford University Press.

- Gluck, P. K. (2010). The Sovereignty of Kings and the Rule of Scientists: A Paradigm Conflict (PDF). The University of Michigan.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur (2002). A Concise History of the Middle East (7th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813338859.

- Greenwood, Timothy (2011). The Emergence of the Bagratuni Kingdoms of Kars and Ani. Mazda Publishers.

- Handy, Lowell K. (1994). Among the host of Heaven: the Syro-Palestinian pantheon as bureaucracy. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0931464843.

- Hartmann, Udo (2001). Das Palmyrenische Teilreich. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07800-9.

- Kabir, Mafizullah (1964). The Buwayhid dynasty of Baghdad, 334/946–447/1055. Calcutta: Iran Society.

- Karlsson, Mattias (2017). "Assyrian Royal Titulary in Babylonia". S2CID 6128352.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kazhdan, Alexander (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- Kobishchanov, Yuri M. (1979). Axum. University of Pennsylvania State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00531-7.

- Kotansky, Roy (1994). "'King of Kings' on an Amulet from Pontus". Greek Magical Amulets: 181–201. doi:10.1007/978-3-663-20312-4_36. ISBN 978-3-663-19965-6.

- Lenczowski, George (1978). Iran under the Pahlavis. Hoover Institution Press. ISBN 978-0817966416.

- Levin, Yigal (2002). "Nimrod the Mighty, King of Kish, King of Sumer and Akkad". Vetus Testamentum. 52 (3): 350–366. doi:10.1163/156853302760197494.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1969). "The Assumption of the Title Shāhānshāh by the Būyids and "The Reign of the Daylam (Dawlat Al-Daylam)"". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 28 (2): 84–108. doi:10.1086/371995. JSTOR 543315. S2CID 159540778.

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1914). The Fundamental Unity of India (from Hindu Sources). Longmans, Green and Company. OCLC 561934377.

- Morrisson, Cécile (2013). Displaying the Emperor's Authority and Kharaktèr on the Marketplace. Routledge. ISBN 978-1409436089.

- National Geographic. Vol. 133, no. 3. March 1968. p. 299.

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)[full citation needed] - Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2009). "Mithridates VI Eupator and Iran".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Oshima, Takayoshi M. (2017). "Nebuchadnezzar's Madness (Daniel 4:30): Reminiscence of a Historical Event or a Legend?".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pasricha, Ashu (1998). Encyclopaedia Eminent Thinkers (vol. 15: The Political Thought Of C. Rajagopalachari). Concept Publishing. ISBN 9788180694950.

- Pinkerton, John (1811). A General Collection of the Best and Most Interesting Travels in all Parts of the World.

- Saikal, Amin; Schnabel, Albrecht (2003). Democratization in the Middle East: Experiences, Struggles, Challenges. United Nations University Press. ISBN 9789280810851.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521766418.

- Schippmann, K. (1986). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 525–536.

- Simonetta, Alberto M. (1966). "Some remarks on the Arsacid coinage of the period 90-57 B.C". The Numismatic Chronicle. 6: 15–40. JSTOR 42665068.

- Sundermann, W. (1988). "BĀNBIŠN". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 7. London et al. pp. 678–679.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Vashalomidze, G. Sophia (2007). Die Stellung der Frau im alten Georgien: georgische Geschlechterverhältnisse insbesondere während der Sasanidenzeit. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447054591.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1989). "Persia or Iran, Persian or Farsi". Iranian Studies. XXII (1). Archived from the original on 2010-10-24.

- Yücel, Muhammet (2017). "A Unique Drachm Coin of Shapur I". Iranian Studies. 50 (3): 331–344. doi:10.1080/00210862.2017.1303329. S2CID 164631548.

Websites

- "6 Bible Verses about Jesus As King Of Kings". bible.knowing-jesus.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- Adebajo, Adekeye (2011). "Gaddafi: the man who would be king of Africa". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Achaemenid Dynasty". iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-03. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- Cartwright, Mark (12 March 2018). "Tushpa". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- CNG. "208. Lot:462". www.cngcoins.com. Classical Numismatic Group. Retrieved 2021-05-24.

ISLAMIC, Seljuks. Great Seljuk. Muhammad Alp Arslan. AH 455-465 / AD 1063-1072. AV Dinar (22mm, 1.90 g, 7h). Herat mint. Dated AH 462 (AD 1069/70).

- "DARIUS iv. Darius II". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- Dzagnidze, Baia (2018). "A Brief History of Georgia's Only Female King". theculturetrip.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Gaddafi: Africa's 'king of kings'". news.bbc.co.uk. 29 August 2008. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Gaddafi named 'king of kings'". news24.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- Goodspeed, Peter (2010). "It is my duty". rezapahlavi.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "IRANIAN IDENTITY iii. MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC PERIOD". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- "King of kings in Media and Urartu". melammu-project.eu. Retrieved 2019-02-19.

- Kiunguyu, Kylie (2018). "Empress Zewditu: Ethiopia's First female head of State". thisisafrica.me. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "NĀDER SHAH". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2019-02-23.

- "Portrait of Fath Ali Shah Seated". hermitagemuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Sahih al-Bukhari 6205". amrayn.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Sahih al-Bukhari 6206". amrayn.com. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Strabo, Geography". perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- Tesfu, Julianna (2008). "Empress Zewditu (1876–1930)". blackpast.org. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- "The Court of Fath 'Ali Shah at the Nowrooz Salaam Ceremony". rct.uk. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- "Tušpa (Van)". livius.org. Retrieved 2019-02-20.