Sallekhana

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

Sallekhana (IAST: sallekhanā), also known as samlehna, santhara, samadhi-marana or sanyasana-marana,[1] is a supplementary vow to the ethical code of conduct of Jainism. It is the religious practice of voluntarily fasting to death by gradually reducing the intake of food and liquids.[2] It is viewed in Jainism as the thinning of human passions and the body,[3] and another means of destroying rebirth-influencing karma by withdrawing all physical and mental activities.[2] It is not considered a suicide by Jain scholars because it is not an act of passion, nor does it employ poisons or weapons.[2] After the sallekhana vow, the ritual preparation and practice can extend into years.[1]

Sallekhana is a vow available to both Jain ascetics and householders.[4] Historic evidence such as nishidhi engravings suggest sallekhana was observed by both men and women, including queens, in Jain history.[1] However, in the modern era, death through sallekhana has been a relatively uncommon event.[5]

There is debate about the practice from a right to life vs right to die and a freedom of religion viewpoint. In 2015, the Rajasthan High Court banned the practice, considering it suicide. In 2016, the Supreme Court of India stayed the decision of the Rajasthan High Court and lifted the ban on sallekhana.[6]

Vow

There are Five Great vows prescribed to followers of Jainism; Ahimsa (non-violence), Satya (not lying), Asteya (not stealing), Brahmacharya (chastity), and Aparigraha (non-possession).[7] A further seven supplementary vows are also prescribed, which include three Gunavratas (merit vows) and four Shiksha vratas (disciplinary vows). The three Gunavratas are: Digvrata (limited movements, limiting one's area of activity), Bhogopabhogaparimana (limiting the use of consumable and non-consumable things), and Anartha-dandaviramana (abstain from purposeless sins). The Shikshavratas include: Samayika (vow to meditate and concentrate for limited periods), Desavrata (limiting movement and space of activity for limited periods), Prosadhopavāsa (fasting for limited periods), and Atithi-samvibhag (offering food to the ascetic).[8][9][10]

Sallekhana is treated as a supplementary to these twelve vows. However, some Jain teachers such as Kundakunda, Devasena, Padmanandin, and Vasunandin have included it under Shikshavratas.[11]

Sallekhana (Sanskrit: Sallikhita) means to properly 'thin out', 'scour out', or 'slender' the passions and the body through gradually abstaining from food and drink.[12][2] Sallekhana is divided into two components: Kashaya Sallekhana (slendering of passions) or Abhayantra Sallekhana (internal slendering) and Kaya Sallekhana (slendering the body) or Bahya Sallekhana (external slendering).[13] It is described as "facing death voluntarily through fasting".[1] According to Jain texts, Sallekhana leads to Ahimsa (non-violence or non-injury), as a person observing Sallekhana subjugates the passions, which are the root cause of Himsa (injury or violence).[14]

Conditions

While Sallekhana is prescribed for both householders and ascetics, Jain texts describe conditions when it is appropriate.[1][15][16] It should not be observed by a householder without the guidance of a Jain ascetic.[17]

Sallekhana is always voluntary, undertaken after the public declaration, and never assisted with any chemicals or tools. Fasting causes thinning away of the body by withdrawing by choice of food and water oneself. As death is imminent, the individual stops all food and water, with full knowledge of colleagues and spiritual counsellor.[18] In some cases, Jains with terminal illness undertake sallekhana, and in these cases, they ask for permission from their spiritual counsellor.[19][note 1] For a successful sallekhana, the death must be with "pure means", voluntary, planned, undertaken with calmness, peace and joy where the person accepts to scour out the body and focuses his or her mind on spiritual matters.[4][2]

Sallekhana differs from other forms of ritual deaths recognized in Jainism as appropriate.[21] The other situations consider ritual death to be better for a mendicant than breaking his or her Five Great vows (Mahavrata).[21] For example, celibacy is one of the Five vows, and ritual death is considered better than being raped or seduced or if the mendicant community would be defamed. A ritual death under these circumstances by consuming poison is believed to be better and allows for an auspicious rebirth.[21]

Procedure

The duration of the practice can vary from a few days to years.[1][22] The sixth part of the Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra describes Sallekhana and its procedure[23] as follows:

Giving up solid food by degrees, one should take to milk and whey, then giving them up, to hot or spiced water. [Subsequently] giving up hot water also, and observing fasting with full determination, he should give up his body, trying in every possible way to keep in mind the pancha-namaskara mantra.

— Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra (127–128)[23]

Jain texts mention five transgressions (Atichara) of the vow: the desire to be reborn as a human, the desire to be reborn as a divinity, the desire to continue living, the desire to die quickly, and the desire to live a sensual life in the next life. Other transgressions include: recollection of affection for friends, recollection of the pleasures enjoyed, and longing for the enjoyment of pleasures in the future.[24][25][26]

The ancient Svetambara Jain text Acharanga Sutra, dated to about 3rd or 2nd century BCE, describes three forms of Sallekhana: the Bhaktapratyakhyana, the Ingita-marana, and the Padapopagamana. In Bhaktapratyakhyana, the person who wants to observe the vow selects an isolated place where he lies on a bed made of straw, does not move his limbs, and avoids food and drink until he dies. In Ingita-marana, the person sleeps on bare ground. He can sit, stand, walk, or move, but avoids food until he dies. In Padapopagamana, a person stands "like a tree" without food and drink until he dies.[1]

Another variation of Sallekhana is Itvara which consists of voluntarily restricting oneself in a limited space and then fasting to death.[21]

History

Textual

The Acharanga Sutra (c. 5th century BCE – c. 1st century BCE) describes three forms of the practice. Early Svetambara[note 2] text Shravakaprajnapti notes that the practice is not limited to ascetics. The Bhagavati Sūtra (2.1) also describes Sallekhana in great detail, as it was observed by Skanda Katyayana, an ascetic of Mahavira. The 4th-century text Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra and the Svetambara text Nava-pada-prakarana also provide detailed descriptions. The Nava-pada-prakarana mentions seventeen methods of "voluntarily chosen death", of which it approves only three as consistent with the teachings of Jainism.[11] The practice is also mentioned in the 2nd century CE Sangam-era poem Sirupanchamoolam.[20]

The Panchashaka makes only a cursory mention of the practice and it is not described in Dharmabindu – both texts by Haribhadra (c. 5th century). In the 9th century text "Ādi purāṇa" by Jinasena the three forms are described. Yashastilaka by Somadeva (10th century) also describes the practice. Other writers like Vaddaradhane (10th century) and Lalitaghate also describe the Padapopagamana, one of its forms. Hemchandra (c. 11th century) describes it in a short passage despite his detailed coverage of the observances of householders (Shravakachara).[1][11][2]

According to Tattvartha Sutra, "a householder willingly or voluntarily adopts Sallekhana when death is very near."[25] According to the medieval era Jain text, Puruşārthasiddhyupāya, both the ascetics and the householder should "court voluntarily death at the end of life", thinking that only sallekhana is a pious death.[27] The Silappadikaram (Epic of the Anklet) by the Jain prince-turned-monk, Ilango Adigal, mentions Sallekhana by the Jain nun, Kaundi Adigal.[20]

Archeological

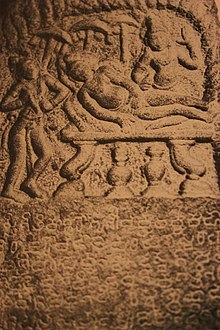

In South India, especially Karnataka, a memorial stone or footprint is erected to commemorate the death of a person who observed Sallekhana. This is known as Nishidhi, Nishidige or Nishadiga. The term is derived from the Sanskrit root Sid or Sad which means "to attain" or "waste away".[1]

These Nishidhis detail the names, dates, the duration of the vow, and other austerities performed by the person who observed the vow. The earliest Nishidhis (6th to 8th century) mostly have an inscription on the rock without any symbols. This style continued until the 10th century when footprints were added alongside the inscription. After the 11th century, Nishidhis are inscribed on slabs or pillars with panels and symbols. These slabs or pillars were frequently erected in mandapas (pillared pavilions), near basadi (temples), or sometimes as an inscription on the door frame or pillars of the temple.[1]

In Shravanabelgola in Karnataka, ninety-three Nishidhis are found ranging from circa the 6th century to the 19th century. Fifty-four of them belong to the period circa the 6th to the 8th century. It is believed that a large number of Nishidhis at Shravanabelgola follow the earlier tradition. Several inscriptions after 600 CE record that Chandragupta Maurya (c. 300 BCE) and his teacher Bhadrabahu observed the vow atop Chandragiri Hill at Sharavnabelagola. Historians such as R. K. Mookerji consider the accounts unproven, but plausible.[28][29][30][31]

An undated inscription in old Kannada script is found on the Nishidhi from Doddahundi near Tirumakudalu Narasipura in Karnataka. Historians such as J. F. Fleet, I. K. Sarma, and E.P. Rice have dated it to 840 or 869 CE by its textual context.[32] The memorial stone has a unique depiction in frieze of the ritual death (Sallekhana) of King Ereganga Nitimarga I (r. 853–869) of the Western Ganga Dynasty. It was raised by the king's son Satyavakya.[33][34] In Shravanabelgola, the Kuge Brahmadeva pillar has a Nishidhi commemorating Marasimha, another Western Ganga king. An inscription on the pillar in front of Gandhavarna Basadi commemorates Indraraja, the grandson of the Rashtrakuta King Krishna III, who died in 982 after observing the vow.[1]

The inscriptions in South India suggest sallekhana was originally an ascetic practice that later extended to Jain householders. Its importance as an ideal death in the spiritual life of householders ceased by about the 12th century. The practice was revived in 1955 by the Digambara monk Acharya Santisagara.[2]

Modern

Sallekhana is a respected practice in the Jain community.[35] It has not been a "practical or general goal" among Svetambara Jains for many years. It was revived among Digambara monks.[2] In 1955, Acharya Shantisagar, a Digambara monk took the vow because of his inability to walk without help and his weak eye-sight.[36][37][38] In 1999, Acharya Vidyanand, another Digambara monk, took a twelve-year-long vow.[39]

Between 1800 and 1992, at least 37 instances of Sallekhana are recorded in Jain literature. There were 260 and 90 recorded Sallekhana deaths among Svetambara and Digambara Jains respectively between 1993 and 2003. According to Jitendra Shah, the Director of L D Institute of Indology in Ahmedabad, an average of about 240 Jains practice Sallekhana each year in India. Most of them are not recorded or noticed.[40] Statistically, Sallekhana is undertaken both by men and women of all economic classes and among the educationally forward Jains. It is observed more often by women than men.[41]

Legality and comparison with suicide

Jain texts make a clear distinction between the Sallekhana and suicide.[42] Its dualistic theology differentiates between soul and matter. The soul is reborn in the Jain belief based on accumulated karma, how one dies contributes to the karma accumulation, and a pious death reduces the negative karmic attachments.[2][43][44] The preparation for sallekhana must begin early, much before the approach of death, and when death is imminent, the vow of Sallekhana is observed by progressively slenderising the body and the passions.[45]

The comparison of Sallekhana with suicide is debated since the early time of Jainism. The early Buddhist Tamil epic Kundalakesi compared it to suicide. It is refuted in the contemporary Tamil Jain literature such as in Neelakesi.[20]

Professor S. A. Jain cites differences between the motivations behind suicide and those behind Sallekhana to distinguish them:

It is argued that it is suicide since there is voluntary severance of life etc. No, it is not suicide, as there is no passion. Without attachment etc, there is no passion in this undertaking. A person who kills himself by means of poison, weapon, etc, swayed by attachment, aversion or infatuation, commits suicide. But he who practices holy death is free from desire, anger, and delusion. Hence it is not suicide.[46]

Champat Rai Jain, a Jainist scholar, wrote in 1934:

Soul is a simple substance and as such immortal. Death is for compounds whose dissolution is termed disintegration and death is when it has reference to a living organism, that is a compound of spirit and matter. By dying in the proper way will is developed, and it is a great asset for the future life of the soul, which, as a simple substance, will survive bodily dissolution and death. The true idea of Sallekhana is only this when death does appear at last one should know how to die, that is one should die like a man, not like a beast, bellowing and panting and making vain efforts to avoid the unavoidable.[47]

Modern-era Indian activists have questioned this rationale, calling the voluntary choice of death an evil similar to sati, and have attempted to legislate and judicially act against this religious custom.[48] Article 21 of the Constitution of India, 1950, guarantees the right to life to all persons within the territory of India and its states. In Gian Kaur vs The State Of Punjab, the state high court ruled, "... 'right to life' is a natural right embodied in Article 21 but suicide is an unnatural termination or extinction of life and, therefore, incompatible and inconsistent with the concept of the right to life".[49]

Nikhil Soni vs Union of India (2006), a case filed in the Rajasthan High Court, citing the Aruna Ramchandra Shanbaug vs Union Of India case related to euthanasia, and the Gian Kaur case, argued, "No person has a right to take his own life consciously, as the right to life does not include the right to end the life voluntarily." So the petitioner cited Sallekhana as suicide and thus punishable under Section 309 (attempt to commit suicide).[50][51] The case also extended to those who helped facilitate the deaths of individuals observing Sallekhana, finding they were culpable under Section 306 (abetment of suicide) with aiding and abetting an act of suicide. It was also argued that Sallekhana "serves as a means of coercing widows and elderly relatives into taking their own lives".[41][52] An attempt to commit suicide was a crime under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code.[51]

In response, the Jain community argued that prohibiting the practice is a violation of their freedom of religion, a fundamental right guaranteed by Article 15 and Article 25 of the Constitution of India.[53][50][41] The book Sallekhana Is Not Suicide by former Justice T. K. Tukol was widely cited in the court[50] which opined that "Sallekhana as propounded in the Jaina scriptures is not suicide."[54]

The Rajasthan High Court stated that "[The Constitution] does not permit nor include under Article 21 the right to take one's own life, nor can it include the right to take life as an essential religious practice under Article 25 of the Constitution". It further added that it is not established that Sallekhana is an essential practise of Jainism and therefore not covered by Article 25 (1). So the High Court banned the practice in August 2015 making it punishable under Sections 306 (abetment of suicide) and 309 (attempt to commit suicide).[55] Members of the Jain community held nationwide protest marches against the ban on Sallekhana.[20][56][57][58]

Advocate Suhrith Parthasarathy criticised the judgement of the High Court and wrote, "Sallekhana is not an exercise in trying to achieve an unnatural death, but is rather a practice intrinsic to a person's ethical choice to live with dignity until death." He also pointed out that the Supreme Court in the Gian Kaur case explicitly recognises the right to live with human dignity within the ambit of the right to life. He further cited that the Supreme Court wrote in the said case, "[The right to life] may include the right of a dying man to also die with dignity when his life is ebbing out. But the right to die with dignity at the end of life is not to be confused or equated with the right to die an unnatural death curtailing the natural span of life."[59][49]

On 31 August 2015, the Supreme Court admitted the petition by Akhil Bharat Varshiya Digambar Jain Parishad and granted leave. It stayed the decision of the High Court and lifted the ban on the practice.[6][60][61][62]

In April 2017, the Indian parliament decriminalised suicide by passing the Mental Healthcare Act, 2017.[63][64]

In Hinduism and Buddhism

There are similar practices in other religions, like Prayopavesa in Hinduism[65] and Sokushinbutsu in Buddhism.[66]

The ancient and medieval scholars of Indian religions discussed suicide, and a person's right to voluntarily choose death. Suicide is approved by Buddhist, Hindu and Jaina texts.[67][68] For those who have renounced the world (sannyasi, sadhu, yati, bhikshu), the Indian texts discuss when ritual choice of death is appropriate and what means of voluntarily ending one's life are appropriate.[69] The Sannyasa Upanishads, for example, discuss many methods of religious death, such as slowing then stopping the consumption of foods and drinks to death (similar to sallekhana), walking into a river and drowning, entering fire, a path of the heroes, and the Great Journey.[70][note 3]

Scholars disagree whether "voluntary religious death" discussed in Indian religions is same as other forms of suicide.[71][72][73]

See also

Notes

- ^ According to Somasundaram, Sallekhana is allowed in Jainism when normal religious life is not possible because of old age, extreme calamities, famine, incurable disease or when a person is nearing their death.[20]

- ^ Svetambara and Digambara are two major sects of Jainism. See Jain schools and branches.

- ^ The heroic path is explained as dying in a just battle on the side of dharma (right, good), and equivalent. The Great Journey is walking north without eating till one dies of exhaustion.[71] A similar practise known as Vadakirutthal (literally facing north) was prevalent in Sangam period in Tamilnadu. It is mentioned in Tamil anthologies such as in Puranaanooru.[20]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sundara, A. "Nishidhi Stones and the ritual of Sallekhana" (PDF). International School for Jain Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dundas 2002, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 115.

- ^ a b Battin 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Dundas 2002, p. 181.

- ^ a b Ghatwai, Milind (2 September 2015), "The Jain religion and the right to die by Santhara", The Indian Express, archived from the original on 22 February 2016

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 4.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 87-91.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 5.

- ^ Pravin K. Shah, Twelve Vows of Layperson Archived 11 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Jainism Literature Center, Harvard University

- ^ a b c Williams 1991, p. 166.

- ^ Kakar 2014, p. 174.

- ^ Settar 1989, p. 113.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Wiley 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Tukol 1976, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Jaini 1998, p. 231.

- ^ Jaini 2000, p. 16.

- ^ Battin 2015, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d e f Somasundaram, Ottilingam; Murthy, AG Tejus; Raghavan, DVijaya (1 October 2016). "Jainism – Its relevance to psychiatric practice; with special reference to the practice of Sallekhana". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 58 (4): 471–474. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.196702. PMC 5270277. PMID 28197009.

- ^ a b c d Battin 2015, p. 48.

- ^ Mascarenhas, Anuradha (25 August 2015), "Doc firm on Santhara despite HC ban: I too want a beautiful death", The Indian Express, archived from the original on 4 December 2015

- ^ a b Champat Rai Jain 1917, pp. 58–64.

- ^ Williams 1991, p. 170.

- ^ a b Tukol 1976, p. 10.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2011, p. 111.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, pp. 112–115.

- ^ Mookerji 1988, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 19–20.

- ^ Sebastian, Pradeep (15 September 2010) [1 November 2009], "The nun's tale", The Hindu, archived from the original on 14 January 2016

- ^ Mallick, Anuradha; Ganapathy, Priya (29 March 2015), "On a spiritual quest", Deccan Herald, archived from the original on 24 September 2015

- ^ Rice 1982, p. 13.

- ^ Sarma 1992, p. 17.

- ^ Sarma 1992, p. 204.

- ^ Kakar 2014, p. 173.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 98.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 100.

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. 104.

- ^ Flügel 2006, p. 353.

- ^ "Over 200 Jains embrace death every year", Express India, 30 September 2006, archived from the original on 14 July 2015

- ^ a b c Braun 2008, pp. 913–924.

- ^ Chapple 1993, p. 102.

- ^ Battin 2015, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Pechilis & Raj 2013, p. 90.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Champat Rai Jain 1934, p. 179.

- ^ Battin 2015, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b "Smt. Gian Kaur vs The State Of Punjab on 21 March, 1996". Indian Kanoon. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b c "Nikhil Soni vs Union Of India & Ors. on 10 August, 2015". Indian Kanoon. 24 May 2003. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Religions: Jainism: Fasting". BBC. 10 September 2009. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015.

- ^ Kumar, Nandini K. (2006). "Bioethics activities in India". Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 12 (Suppl 1): S56–65. PMID 17037690.

- ^ article 15 of India Constitution

- ^ Tukol 1976, p. Preface.

- ^ Vashishtha, Swati (10 August 2015), "Rajasthan HC bans starvation ritual 'Santhara', says fasting unto death not essential tenet of Jainism", News 18, archived from the original on 11 October 2016

- ^ "Jain community protests ban on religious fast to death", Yahoo News, Indo Asian News Service, 24 August 2015, archived from the original on 16 October 2015

- ^ Ghatwai, Milind; Singh, Mahim Pratap (25 August 2015), "Jains protest against Santhara order", The Indian Express, archived from the original on 26 August 2015

- ^ "Silent march by Jains against Rajasthan High Court order on 'Santhara'", The Economic Times, Press Trust of India, 24 August 2015, archived from the original on 27 August 2015

- ^ Parthasarathy, Suhrith (24 August 2015), "The flawed reasoning in the Santhara ban", The Hindu, archived from the original on 14 January 2016

- ^ Anand, Utkarsh (1 September 2015), "Supreme Court stays Rajasthan High Court order declaring 'Santhara' illegal", The Indian Express, archived from the original on 5 September 2015

- ^ "SC allows Jains to fast unto death", Deccan Herald, Press Trust of India, 31 August 2015, archived from the original on 13 September 2015

- ^ Rajagopal, Krishnadas (28 March 2016) [1 September 2015], "Supreme Court lifts stay on Santhara ritual of Jains", The Hindu, archived from the original on 30 November 2016

- ^ "Mental health bill decriminalising suicide passed by Parliament". The Indian Express. 27 March 2017. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ THE MENTAL HEALTHCARE ACT, 2017 (PDF). New Delhi: The Gazette of India. 7 April 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 April 2017.

- ^ Timms 2016, p. 167.

- ^ Hayes 2016, p. 16.

- ^ Arvind Sharma 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Olivelle 2011, p. 208 footnote 7.

- ^ Olivelle 2011, pp. 207–229.

- ^ Olivelle 2011, pp. 208–223.

- ^ a b Olivelle 1992, pp. 134 footnote 18.

- ^ Olivelle 1978, pp. 19–44.

- ^ Sprockhoff, Joachim Friedrich (1979). "Die Alten im alten Indien Ein Versuch nach brahmanischen Quellen". Saeculum (in German). 30 (4). Bohlau Verlag: 374–433. doi:10.7788/saeculum.1979.30.4.374. S2CID 170777592.

Sources

- Battin, Margaret Pabst (11 September 2015), The Ethics of Suicide: Historical Sources, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-938582-9

- Braun, Whitny (1 December 2008), "Sallekhana: The ethicality and legality of religious suicide by starvation in the Jain religious community", Medicine and Law, 27 (4): 913–24, ISSN 0723-1393, PMID 19202863

- Chapple, Christopher (1993), Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-9877-8

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), London and New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Flügel, Peter, ed. (2006), Studies in Jaina History and Culture, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-203-00853-9

- Hayes, Patrick J., ed. (2016), Miracles: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Supernatural Events from Antiquity to the Present, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-61069-599-2

- Jain, Champat Rai (1917), The Ratna Karanda Sravakachara, The Central Jaina Publishing House,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Champat Rai (1934), Jainism and World Problems: Essays and Addresses, Jaina Parishad,

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jain, Prof. S. A. (1992) [First edition 1960], Reality (English Translation of Srimat Pujyapadacharya's Sarvarthasiddhi) (Second ed.), Jwalamalini Trust

- Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvarthsutra (1st ed.), Uttarakhand: Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1

- Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya: Realization of the Pure Self, With Hindi and English Translation, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (2000), Collected Papers On Jaina Studies (First ed.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1691-9

- Kakar, Sudhir (2014), "A Jain Tradition of Liberating the Soul by Fasting Oneself", Death and Dying, Penguin UK, ISBN 978-93-5118-797-4

- Mookerji, Radha Kumud (1988) [first published in 1966], Chandragupta Maurya and his times (4th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0433-3

- Olivelle, Patrick (1978), Ritual suicide and the rite of renunciation [Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde Südasiens und Archiv für Indische Philosophie Wien], vol. 22, archived from the original on 12 May 2017

- Olivelle, Patrick (1992), The Samnyasa Upanisads: Hindu Scriptures on Asceticism and Renunciation, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-536137-7

- Olivelle, Patrick (2011), Ascetics and Brahmins: Studies in Ideologies and Institutions, Anthem Press, ISBN 978-0-85728-432-7,

In spite of the general rule forbidding suicide, Buddhist literature abounds with instances of religious suicide

- Pechilis, Karen; Raj, Selva J. (2013), South Asian Religions: Tradition and Today, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-44851-2

- Rice, E.P. (1982) [1921], A History of Kanarese Literature, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, ISBN 81-206-0063-0

- Sarma, I.K. (1992), Temples of the Gangas of Karnataka, New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, ISBN 0-19-560686-8

- Settar, S (1989), Inviting Death, ISBN 90-04-08790-7

- Sharma, Arvind (1988), Sati: Historical and Phenomenological Essays, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ, ISBN 978-81208-046-47

- Timms, Olinda (2016), Biomedical Ethics, Elsevier, ISBN 978-81-312-4416-6

- Tukol, Justice T. K. (1976), Sallekhanā is Not Suicide (1st ed.), Ahmedabad: L. D. Institute of Indology

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009) [1949], The A to Z of Jainism, vol. 38, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8

- Williams, Robert (1991), Jaina Yoga: A Survey of the Mediaeval Śrāvakācāras, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0775-4

External links

- Sallekhana as a religious right, Whitny Braun, Claremont Graduate University (2014)

- Fasting To The Death: Is It A Religious Rite Or Suicide?, National Public Radio (2015)