Sino-Soviet border conflict

| Sino-Soviet border conflict | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and the Sino-Soviet split | |||||||||

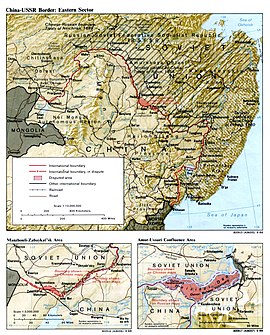

Disputed areas in the Argun and Amur rivers. Damansky/Zhenbao is to the south-east, north of the lake | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 658,002 | 814,001 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

60 killed 95 wounded (Soviet sources)[3] 27 Tanks/APCs destroyed (Chinese sources)[4] 1 Command Car (Chinese sources)[5] Dozens of trucks destroyed (Chinese sources)[6] One Soviet T-62 tank captured[7] |

72 killed and 68 wounded (Chinese sources) 200~800 killed[8] (Soviet sources)[3] | ||||||||

The Sino-Soviet border conflict was a seven-month undeclared military conflict between the Soviet Union and China at the height of the Sino-Soviet split in 1969. The most serious of these border clashes, which brought the world's two largest communist states to the brink of war, occurred in March 1969 in the vicinity of Zhenbao (Damansky) Island on the Ussuri (Wusuli) River, near Manchuria. The conflict resulted in a ceasefire, with a return to the status quo.

Background

History

Under the governorship of Sheng Shicai (1933–1944) in northwest China's Xinjiang province, China's nationalist Kuomintang recognized for the first time the ethnic category of a Uyghur people, following Soviet ethnic policy.[9] This ethnogenesis of a "national" people eligible for territorialized autonomy broadly benefited the Soviet Union, which organized conferences in Fergana and Semirechye (in Soviet Central Asia), in order to cause "revolution" in Altishahr (southern Xinjiang) and Dzungaria (northern Xinjiang).[10][9]

Both the Soviet Union and the White movement covertly allied with the Ili National Army to fight against the Kuomintang in the Three Districts Revolution. Although the mostly Muslim Uyghur rebels participated in pogroms against Han Chinese generally, the turmoil eventually resulted in the replacement of Kuomintang rule in Xinjiang with that of the Communist Party of China.[10]

Soviet historiography and more specifically Soviet "Uyghur Studies" were politicized in increasing measure to match the tenor of the Sino-Soviet split from the 1960s and 1970s. One Soviet Turkologist named Tursun Rakhminov, who worked for the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, argued that it was the modern Uyghurs who founded the ancient Toquz Oghuz Country (744–840), the Kara-Khanid Khanate (840–1212), and so forth. These premodern states' wars against Chinese dynasties were cast as struggles for national liberation by the Uyghur ethnic group. Soviet historiography was not consistent on these questions: when Sino-Soviet relations were warmer, for example, the Three Districts Revolution was portrayed by Soviet historians as part of anti-Kuomintangs during the Chinese Civil War, and not an anti-Chinese bid for national liberation. The Soviet Union also encouraged migration of Uyghurs to its territory in Kazakhstan along the 4,380 km (2,738 mi) border. In May 1962, 60,000 Uyghurs from Xinjiang Province crossed the frontier into the Soviet Union, fleeing the famine and economic chaos of the Great Leap Forward.[11]

| Sino-Soviet border conflict | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zhenbao Island and the border. | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中蘇邊界衝突 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中苏边界冲突 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 珍寶島自衛反擊戰 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 珍宝岛自卫反击战 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Zhenbao Island self-defense | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||||

| Russian | Пограничный конфликт на острове Даманский | ||||||||||||

| Romanization | Pograničnyj konflikt na ostrove Damanskij | ||||||||||||

Amid heightening tensions, the Soviet Union and China began border talks. Despite the Soviet Union having granted all of the territory of the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo to Mao's communists in 1945, decisively assisting the communists in the Chinese Civil War, the Chinese now indirectly demanded territorial concessions on the basis that the 19th-century treaties transferring ownership of the sparsely populated Outer Manchuria, concluded by Qing dynasty China and the Russian Empire, were "Unequal Treaties", and amounted to annexation of rightful Chinese territory. Moscow would not accept this interpretation, but by 1964 the two sides did reach a preliminary agreement on the eastern section of the border, including Zhenbao Island, which would be handed over to China.[12]

In July 1964, Mao Zedong, in a meeting with the Japanese Socialist Party delegation, stated that Russia had stripped China of vast territories in Siberia and the Far East as far as Kamchatka. Mao stated that China still had not presented a bill for this list. These comments were leaked to the public. Outraged, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev then refused to approve the border agreement.[12]

Geography

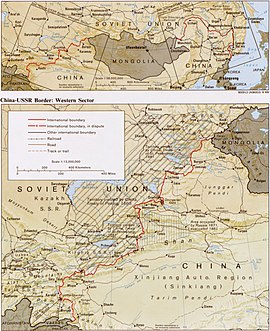

The border dispute in the west centered on 52,000 square kilometres (20,000 sq mi) of Soviet-controlled land in the Pamirs that lay on the border of Xinjiang and the Soviet Republic of Tajikistan. In 1892 the Russian Empire and the Qing Dynasty had agreed that the border would consist of the ridge of the Sarikol Range, but the exact border remained contentious throughout the 20th century. In the 1960s the Chinese began to insist that the Soviet Union should evacuate the region.

From around 1900, after the Treaty of Peking (1860) had assigned Outer Manchuria (Primorskiy Kray) to Russia, the eastern part of the Sino-Soviet border had mainly been demarcated by three rivers, the Argun River from the tripartite junction with Mongolia to the north tip of China, running southwest to northeast, then the Amur River to Khabarovsk from northwest to southeast, where it was joined by Ussuri River running south to north. The Ussuri River was demarcated in a non-conventional manner: the demarcation line ran along the right (Chinese) side of the river, putting the river itself with all its islands in Russian possession.

"The modern method (used for the past 200 years) of demarcating a river boundary between states today is to set the boundary at either the median line (ligne médiane) of the river or around the area most suitable for navigation under what is known as the 'thalweg principle.'"[13]

China claimed these islands, as they were located on the Chinese side of the river (if demarcated according to international rule using shipping lanes). The USSR wanted (and by then, already effectively controlled) almost every single island along the rivers.

Chinese and Soviet government views

The USSR had nuclear weapons for a longer time than China, so the Chinese adopted an asymmetric deterrence strategy that threatened a large conventional "People's War" in response to a Soviet counterforce first-strike. Chinese numerical superiority was the basis of its strategy to deter a Soviet nuclear attack. Since 1949, Chinese strategy as articulated by Mao Zedong emphasized the superiority of "man over weapons". While weapons were certainly an important component of warfare, Mao argued that they were "not the decisive factor; it is people, not things, that are decisive. The contest of strength is not only a contest of military and economic power, but also a contest of human power and morale". To Mao 'non-material' factors like 'creativity, flexibility and high morale' were also 'critical determinants in warfare'.[7]

The Soviets were not confident they could win such a conflict. A large Chinese incursion could threaten strategic centers in Blagoveshchensk, Vladivostok, and Khabarovsk, as well as crucial nodes of the Trans-Siberian Railroad. According to Arkady Shevchenko, a high-ranking Russian defector to the United States, "The Politburo was terrified that the Chinese might make a mass intrusion into Soviet territory". A nightmare vision of invasion by millions of Chinese made the Soviet leaders almost frantic. "Despite our overwhelming superiority in weaponry, it would not be easy for the USSR to cope with an assault of this magnitude". Given China's "vast population and deep knowledge and experience in guerrilla warfare", if the Soviets launched an attack on China's nuclear program they would surely become "mired in an endless war".[7]

Concerns about Chinese manpower and its "people's war" strategy ran so deep that some bureaucrats in Moscow argued the only way to defend against a massive conventional onslaught was to use nuclear weapons. Some even advocated deploying nuclear mines along the Sino-Soviet border. By threatening to initiate a prolonged conventional conflict in retaliation for a nuclear strike, Beijing employed an asymmetric deterrence strategy intended to convince Moscow that the costs of an attack would outweigh the benefits. China had found its strategic rationale. While most Soviet military specialists did not fear a Chinese nuclear reprisal, believing that China's arsenal was so small, rudimentary and vulnerable that it could not survive a first strike and carry out a retaliatory attack, there was great concern about China's massive conventional army. Nikolai Ogarkov, a senior Soviet military officer, believed that a massive nuclear attack "would inevitably mean world war". Even a limited counterforce strike on China's nuclear facilities was dangerous, Ogarkov argued, because a few nuclear weapons would "hardly annihilate" a country the size of China and in response China would "fight unrelentingly".[7]

Eastern border: Heilongjiang (1969)

The Soviet Border Service started to report intensifying Chinese military activity in the region during the early 1960s. The tensions were rising – first, slowly, then, with the advent of the Cultural Revolution, much faster. The number of troops on both sides of the Sino-Soviet border increased dramatically after 1964. Militarily, in 1961, the USSR had 225,000 men and 200 aircraft at that border; in 1968, there were 375,000 men, 1,200 aircraft and 120 medium-range missiles. China had 1.5 million men stationed at the border and it had already tested its first nuclear weapon (the 596 Test in October 1964, at Lop Nur basin). Political rhetoric on both sides was getting increasingly hostile.

The key moment in escalating Sino-Soviet tensions was the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia on 20–21 August 1968 and with it the proclamation of the Brezhnev Doctrine that the Soviet Union had the right to overthrow any Communist government that was diverging from Communism as defined by the Kremlin. Mao saw the Brezhnev doctrine as the ideological justification for a Soviet invasion of China to overthrow him and launched a massive propaganda campaign attacking the invasion of Czechoslovakia, despite the fact that he had earlier condemned the Prague Spring as "revisionism".[14] On 21 August 1968, the Romanian leader Nicolae Ceaușescu gave a famous speech in Revolution Square in Bucharest denouncing the invasion of Czechoslovakia that was widely seen both in Romania and abroad as virtual declaration of independence from the Soviet Union. Romania started to move away from being in the Soviet sphere of influence to being in the Chinese sphere of influence. Speaking at a banquet held at the Romanian embassy in Beijing on 23 August 1968, the Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai denounced the Soviet Union for "fascist politics, great power chauvinism, national egoism and social imperialism", going on to compare the invasion of Czechoslovakia to the American war in Vietnam and more pointedly to the policies of Adolf Hitler towards Czechoslovakia in 1938–39.[14] Zhou ended his speech with a barely veiled call for the people of Czechoslovakia to wage guerrilla war against the Red Army.[14]

The Chinese historian Li Danhui wrote in "Already in 1968, China began preparations to create a small war on the border".[15] She noted that prior to March 1969 that the Chinese troops had twice attempted to provoke a clash along the border, "but the Soviets, feeling weak, did not accept the Chinese challenge and retreated."[15] Another Chinese historian, Yang Kuisong, wrote "There were already significant preparations in 1968, but the Russians did not come, so the planned ambush was not successful."[15]

Battle of Zhenbao Island

| Zhenbao (Damansky) Island incident | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 100 at the beginning[18] | 300[18] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

248 killed 62 wounded[18] | 29 killed[19] | ||||||||

On 2 March 1969, a group of People's Liberation Army (PLA) troops ambushed Soviet border guards on Zhenbao Island. According to the Chinese sources, the Soviets suffered 58 dead, including a senior colonel, and 94 wounded. The Chinese losses were reported as 29 dead.[18] According to the Soviet/Russian sources, no fewer than 248 Chinese troops were killed on the island and on the frozen river,[20] while 32 Soviet border guards were killed, 14 wounded.[21]

To this day, each side blames the other for the start of the conflict. However, a scholarly consensus has emerged that the 1969 Sino-Soviet border crisis was a premeditated act of aggression orchestrated by the Chinese side. The American scholar Lyle J. Goldstein noted that Russian documents released since the glasnost era paint an unflattering picture of the Red Army command in the Far East with senior generals surprised by the outbreak of the fighting and of Red Army units haphazardly committed to action in a piecemeal style, but all of the documents speak of the Chinese as the aggressors.[22] Even most Chinese historians now agree that on 2 March 1969, PLA forces planned and executed an ambush, which took the Soviets completely by surprise.[15] Why the Chinese leadership opted for such an offensive measure against the Soviet Union remains a disputed question.[23]

On 2 March 1969, Damansky (Zhenbao) Island was under Soviet control, regularly patrolled by Soviet border guards. Occasional incursions of Chinese peasants and fishermen were blocked and repelled without use of deadly force. The Chinese attack on 2 March was led by 3 platoons of specially trained troops, supported by one artillery and two mortar units. It started unprovoked with the illegal crossing of the Sino-Soviet border by a group of 77 PLA soldiers, and took the Soviets by surprise. When a squad of seven men under the command of Sen Lt Ivan Strelnikov approached the Chinese with a verbal demand to leave the island, the Chinese troops opened fire, killing them all. This started a day of hostilities that saw a Chinese regular army detachment attacking two small groups of Soviet border guards comprising no more than 30 soldiers.[citation needed]

The Chinese claim a different version of the conflict. The Chinese Cultural Revolution increased tensions between China and the USSR. This led to brawls between border patrols, and shooting broke out in March 1969. The USSR responded with tanks, armoured personnel carriers (APCs), and artillery bombardment. Over three days, the PLA successfully halted Soviet penetration and eventually evicted all Soviet troops from Zhenbao Island. During this skirmish the Chinese deployed two reinforced infantry platoons with artillery support. Chinese sources state the Soviets deployed some 60 soldiers and six BTR-60 amphibious APCs, and in a second attack some 100 troops backed up by 10 tanks and 14 APCs including artillery.[18] The PLA had prepared for this confrontation for two to three months. From among the units, the PLA selected 900 soldiers commanded by army staff members with combat experience. They were provided with special training and special equipment. Then they were secretly dispatched to take position on Zhenbao Island in advance.[6] Chinese General Chen Xilian stated the Chinese had won a clear victory on the battlefield.[6]

On 15 March the Soviets dispatched another 30 soldiers and six combat vehicles to Zhenbao Island. After an hour of fighting, the Chinese had destroyed two of the Soviet vehicles. A few hours later the Soviets sent a second wave with artillery support. The Chinese would destroy five more Soviet combat vehicles. A third wave would be repulsed by effective Chinese artillery which destroyed one Soviet tank and four APCs while damaging two other APCs. By the end of the day, with the Chinese in full control of the island, Soviet general O.A. Losik ordered to deploy then-secret BM-21 "Grad" multiple rocket launchers. The Soviets fired 10,000 artillery rounds in a nine-hour engagement with the Chinese along with 36 sorties.[24] The attack was devastating for the Chinese troops and materiel. Chinese troops left their positions on the island, following which the Soviets withdrew back to their positions on the Russian bank of the Ussuri river.[25] On 16 March 1969, the Soviets entered the island to collect their dead; the Chinese held their fire. On 17 March 1969, the Soviets tried to recover a disabled T-62 tank from the island, but their effort was repelled by Chinese artillery.[18] On 21 March, the Soviets sent a demolition team attempting to destroy the tank. The Chinese opened fire and thwarted the Soviets.[18] With the help of divers of the Chinese navy, the PLA pulled the T-62 tank onshore. The tank was later given to the Chinese Military Museum. Until 1991, the island remained contested.

Soviet combat heroes

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2018) |

Five Soviet soldiers were awarded the top honour of the Hero of the Soviet Union for bravery and valor during the Damansky conflict. Col. D.V. Leonov led the group of four T-62 tanks in a counter-attack on 15 March and was killed by a Chinese sniper when leaving the destroyed vehicle. Sen. Lt. Ivan Strelnikov tried to negotiate a peaceful withdrawal of the Chinese commandos from the island and was killed for his troubles while talking to the enemy.[26]

Sen. Lt. Vitaly Bubenin led a relief mission of 23 soldiers from the nearby border guards outpost and conducted a BTR-60 raid into the Chinese rear that allegedly left 248 attackers dead. Junior sergeant Yuri Babansky assumed command in a battle on 2 March, when the enemy had a 10:1 superiority, after the senior lieutenant Strelnikov was killed. He later led combat search and rescue teams that retrieved bodies of Sen. Lt Strelnikov and Col. Leonov. Junior sergeant Vladimir Orekhov took part in the 15 March battle. As a machine-gunner he was part of the first attacking line against the Chinese forces encamped on the island, he destroyed the enemy machine gun nest, and was wounded twice but continued fighting until he died of his wounds. High military orders of Lenin, The Red Banner, The Red Star and Glory were awarded to 54 soldiers and officers; medals "For Courage" and "For Battle Merit" – to 94 border guards and servicemen.

Chinese combat heroes

During the Zhenbao Island clashes with the Soviet Army in March 1969 one Chinese RPG team, Hua Yujie and his assistant Yu Haichang destroyed four Soviet APCs and achieved more than ten kills. Hua and Yu received the accolade "Combat Hero" from the CMC, and their action was commemorated on a postage stamp.[27]

Diplomacy

On 17 March 1969, an emergency meeting of the Warsaw Pact organisation was called in Budapest by Brezhnev with the aim of condemning China.[28] The meeting turned acrimonious as Romania's Nicolae Ceaușescu refused, despite considerable Soviet pressure, to sign the statement condemning China.[28] Ceaușescu's intransigence led to no statement being issued in what was widely seen as a Soviet diplomatic defeat.[28] The next day saw a meeting of the delegations representing 66 Communist Parties in Moscow to discuss the preparations for a world summit of Communist Parties in Moscow on 5 June 1969.[28] A Soviet motion to condemn China failed with the delegations representing the Communist Parties of Romania, India, Spain, Switzerland, and Austria all supporting the Chinese position that it was the Soviet Union that attacked China rather than vice versa.[28]

On 21 March 1969, the Soviet Premier, Alexei Kosygin, tried to phone Mao with the aim of discussing a ceasefire.[28] The Chinese operator who took Kosygin's call rather rudely called him a "revisionist element" and hung up.[28] Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, who wanted to take up Kosygin's ceasefire offer, was shocked by what he regarded as Mao's recklessness, saying: "The two countries are at war, one cannot chop the messenger."[28] Diplomats from the Soviet Embassy in Beijing spent much of 22 March vainly attempting to get hold of Mao's private phone number, in order that Kosygin could call him to discuss peace.[28] On 22 March 1969, Mao had a meeting with the four marshals who commanded the PLA troops in the border regions with the Soviet Union to begin preparations for a possible all-out war.[29] Zhou repeatedly urged Mao to discuss a ceasefire though also agreed with Mao's refusal to take phone calls from Kosygin.[29] In an effort to placate Zhou, Mao told him: "Immediately prepared to hold diplomatic negotiations".[29]

Between 1–24 April 1969, the 9th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party took place and Mao officially proclaimed the end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution he had begun in May 1966.[29] Despite the official end of the Cultural Revolution, the Congress elected to key positions followers of the ultra-leftwing factions associated with Mao's powerful wife, Jiang Qing, and the Defense Minister Lin Biao.[29] Both Jiang and Lin favored a hard-line towards the Soviet Union.[29] At the same time, Mao had ordered preparations for a "defense in depth" along the border as by this time there were real fears that the border crisis would escalate into all-out war.[29] In a bid to repair China's image abroad, which had been badly damaged by the Cultural Revolution, on 1 May 1969, Mao invited diplomats from several Third World nations to attend the May Day celebrations in Beijing.[29] To the assembled diplomats, Mao formally apologized for the attacks by the Red Guards against diplomats in China together with the smashing up of the embassies in Beijing in 1967.[30] Mao claimed not to be aware of the fact that the xenophobic Red Guard had been beating up and sometimes killing foreigners living in China during the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, Mao announced that for the first time since the Cultural Revolution he would send out ambassadors to represent China abroad (most of the Chinese ambassadors had been recalled and executed during the Cultural Revolution with no replacements being sent out).[30] By this time, Mao had felt that China's isolation caused by the Cultural Revolution had become a problem with his nation on the brink of a war with the Soviet Union.[30]

On 5 May 1969, Kosygin traveled to India, an archenemy of China's ever since it had been defeated in the 1962 war, to discuss with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi an anti-Chinese Soviet-Indian alliance.[30] Between 14–19 May 1969, Nikolai Podgorny visited North Korea with the aim of making an offer to pull Kim Il-sung away from the Chinese orbit.[30] Kim declined to move away from China, and in a show of support for Mao, North Korea sent no delegation to the world conference of Communist Parties that was held in Moscow in June 1969.[30]

On 17 June 1969, the Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, who had long been an advocate of normalizing American relations with China, wrote a letter in consultation with the White House urging that he be allowed to visit China and to meet Mao to discuss measures to improve Sino-American relations.[31] The letter was sent to King Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia with the request to pass on to Mao, and by 26 July 1969 Mansfield's letter arrived in Beijing.[32] The Chinese reply was harsh with Zhou giving a speech accusing the United States of "aggression" in Vietnam and of "occupation" of Taiwan, which Zhou asserted was rightfully a part of China.[32] On 1 August 1969, United States President Richard Nixon visited Pakistan, a close ally of China owing to their shared hatred of India, to ask General Yahya Khan to pass a message to Mao saying he wanted to normalize relations with China, especially given the crisis with the Soviet Union.[32] On 2–3 August 1969 Nixon visited Romania to meet with Ceaușescu and to ask him to pass along the same message to Mao.[32] Ceaușescu agreed to do so, and on 7 September 1969 the Romanian Prime Minister Ion Gheorghe Maurer, who was in Hanoi to attend the funeral of Ho Chi Minh, took Zhou aside to tell him that Nixon wanted an opening to China.[33]

Western border: Xinjiang (1969)

| Tielieketi incident | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Western part of the China-USSR border, 1988 map | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 100 | 300 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

28 killed 1 captured 40 wounded[34][35] |

2 killed 10 wounded | ||||||||

Further border clashes occurred in August 1969, this time along the western section of the Sino-Soviet border in Xinjiang. After the Tasiti incident and the Bacha Dao incident, the Tielieketi Incident finally broke out. Chinese troops suffered 28 losses. Heightened tensions raised the prospect of an all-out nuclear exchange between China and the Soviet Union.[36]

The Funeral of Ho Chi Minh

The decisive event that stopped the crisis from escalating into all-out war was the death of Ho Chi Minh on 3 September 1969.[33] The funeral of Ho in Hanoi was attended by both Zhou and Kosygin, though at different times. Zhou flew out of Hanoi to avoid being in the same room as Kosygin.[33] The possibility of North Vietnam's leading supporters going to war with one another alarmed the North Vietnamese. During the funeral of Ho, messages were exchanged between the Soviet and Chinese sides via the North Vietnamese.[37] At the same time, Nixon's message via Maurer had reached the Chinese, and it was decided in Beijing to "whet the appetite of the Americans" by making China appear stronger.[37] Zhou argued that a war with the Soviet Union would weaken China's hand vis-a-vis the United States.[37] The Chinese were more interested in the possibility of a rapprochement with the United States as a way of re-acquiring Taiwan than in having the United States as an ally against the Soviet Union. After attending Ho's funeral, the airplane taking Kosygin back to Moscow was denied permission to use Chinese air space, forcing it to land for refuelling in Calcutta.[37] While in India, Kosygin received the message via the Indian government that the Chinese were willing to discuss peace, causing him to fly back to Beijing instead.[37]

Assessment

Near-war state

In the early 1960s, the United States had "probed" the level of Soviet interest in joint action against Chinese nuclear weapons facilities; now the Soviets probed what the United States' reaction would be if the USSR attacked the facilities.[38] While noting that "neither side wishes the inflamed border situation to get out of hand", the Central Intelligence Agency in August 1969 described the conflict as having "explosive potential" in the President's Daily Briefing.[39] The agency stated that "the potential for a war between them clearly exists", including a Soviet attack on Chinese nuclear facilities, while China "appears to view the USSR as its most immediate enemy".[40]

As war fever gripped China, Moscow and Beijing took steps to lower the danger of a large-scale conflict. On 11 September 1969, Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin, on his way back from the funeral of Ho Chi Minh, stopped over in Beijing for talks with his Chinese counterpart, Zhou Enlai. Symbolic of the frosty relations between the two communist countries, the talks were held at Beijing airport. The two premiers agreed to return ambassadors previously recalled and to begin border negotiations.

Possible reasons for attack

The view on the reasoning and consequences of the conflict differ. Western historians believe the events at Zhenbao Island and the subsequent border clashes in Xinjiang were mostly caused by Mao's using Chinese local military superiority to satisfy domestic political imperatives in 1969.[41] Yang Kuisong concludes that "the [Sino-Soviet] military clashes were primarily the result of Mao Zedong's domestic mobilization strategies, connected to his worries about the development of the Cultural Revolution."[42]

Russian historians point out that the consequences of the conflict stem directly from the desire of the PRC to take a leading role in the world and to strengthen ties with the US. According to the 2004 Russian documentary film, Damansky Island Year 1969, Chairman Mao sought to elevate his country from the world's periphery and to place it at the centre of world politics.[43] Other analysts say the Chinese intended their attack on Zhenbao to deter future Soviet invasions by demonstrating that China could not be 'bullied.[7]

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the conflict, China gained newfound respect in the US, who began seeing it as a competent ally against the USSR during the Cold War.

Seen against the background of the Brezhnev-Nixon détente talks, the Damansky incident could serve the double purpose of undermining the Soviet image of a peace-loving country—if the USSR chose to respond with a massive military operation against the invaders—or demonstrating Soviet weakness, if the Chinese attack had been left without response. The killing of Soviet servicemen on the border signaled to the US that China had graduated into high politics and was ready for dialog.

After the conflict, the US showed interest in strengthening ties with the Chinese government by secretly sending Henry Kissinger to China for a meeting with Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in 1971, during the so-called Ping Pong Diplomacy, paving the way for Richard Nixon to visit China and meet with Mao Zedong in 1972.[44]

China's relations with the USSR remained sour after the conflict, despite the border talks, which began in 1969 and continued inconclusively for a decade. Domestically, the threat of war caused by the border clashes inaugurated a new stage in the Cultural Revolution; that of China's thorough militarization. The 9th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, held in the aftermath of the Zhenbao Island incident, confirmed Defense Minister Lin Biao as Mao's heir apparent. Following the events of 1969, the Soviet Union further increased its forces along the Sino-Soviet border, and in the Mongolian People's Republic.

Overall, the Sino-Soviet confrontation, which reached its peak in 1969, paved the way to a profound transformation in the international political system.

Border negotiations 1990s–present

Serious border demarcation negotiations did not occur until shortly before the end of the Soviet Union in 1991. In particular, both sides agreed that Zhenbao Island belonged to China. (Both sides claimed the island was under their control at the time of the agreement.) On 17 October 1995, an agreement over the last 54 kilometres (34 mi) stretch of the border was reached, but the question of control over three islands in the Amur and Argun rivers was left to be settled later.

In a border agreement between Russia and China signed on 14 October 2003, that dispute was finally resolved. China was granted control over Tarabarov Island (Yinlong Island), Zhenbao Island, and approximately 50% of Bolshoy Ussuriysky Island (Heixiazi Island), near Khabarovsk. China's Standing Committee of the National People's Congress ratified this agreement on 27 April 2005, with the Russian Duma following suit on 20 May. On 2 June, Chinese Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing and Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergei Lavrov exchanged the ratification documents from their respective governments.[45]

On 21 July 2008, Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi and his Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, signed an additional Sino-Russian Border Line Agreement marking the acceptance of the demarcation of the eastern portion of the Chinese-Russian border in Beijing, China. An additional protocol with a map affiliated on the eastern part of the borders both countries share was signed. The agreement also includes the PRC gaining ownership of Yinlong / Tarabarov Island and half of Heixiazi / Bolshoi Ussuriysky Island.[46]

In the 21st century, the Chinese Communist Party's version of the conflict, present on many official websites, describes the events of March 1969 as a Soviet aggression against China.[47]

In popular culture

- The map-based war game "The East is Red: the Sino-Soviet War" (based on a hypothetical war using publicly known orders of battle on either side) was published with an accompanying article in issue No. 42 of Strategy and Tactics magazine by Simulations Publications, Inc. in 1974.

- Wargame: Red Dragon features a hypothetical war between these two powers based on this border conflict.

- Graviteam Tactics: Operation Star features a general depiction of the combat in its DLC Zhalanaskol 1969[48]

See also

- History of the Soviet Union (1964–1982)

- History of the People's Republic of China

- Foreign relations of the People's Republic of China

- Soviet Invasion of Xinjiang

- Xinjiang War (1937)

- Pei-ta-shan Incident

References

- ^ "Exploring Chinese History :: Politics :: Conflict and War :: Soviet Aggression". Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ China signs border demarcation pact with Russia Archived 11 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. 21 July 2008.

- ^ a b Ryabushkin, D. A. (2004). Мифы Даманского. АСТ. pp. 151, 263–264. ISBN 978-5-9578-0925-8.

- ^ Kuisong, pp. 25, 26, 29

- ^ Kuisong, p. 25

- ^ a b c Kuisong, pp. 28–29

- ^ a b c d e Gerson, Michael S. (November 2010) The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969 Archived 10 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Center for Naval Analyses

- ^ Baylis, John (1987). Contemporary Strategy: Theories and concepts. Lynne Rienner Pub. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8419-0929-8.

- ^ a b Millward, James (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-85065-818-4.

- ^ a b Forbes, Andrew (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 175, 178, 188. ISBN 0521255147.

- ^ Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 38–41. ISBN 9780754670414.

- ^ a b Wang, Zhen 王楨. Huángpái dàfàngsòng 皇牌大放送, "Duóbǎo bīngyuán——ZhōngSū Zhēnbǎo dǎo chōngtú 45 zhōunián jì" 奪寶冰原——中蘇珍寶島衝突45周年記 [Fighting for the treasure on icefield—Sino-Soviet Zhenbao Island conflict 45th anniversary]. Aired 5 April 2014 on Phoenix Television. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NtzIuc5FIMk Archived 29 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shah, Sikander Ahmed (February 2012). "River Boundary Delimitation and the Resolution of the Sir Creek Dispute Between Pakistan and India" (PDF). Vermont Law Review. 34 (357): 364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Rea 1975, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Goldstein 2003, p. 59.

- ^ Yang, Kuisong (2000). "The Sino-Soviet Border Clash of 1969: From Zhenbao Island to Sino-American Rapprochement". Cold War History. 1: 21–52. doi:10.1080/713999906.

- ^ "Zhēnbǎo dǎo zìwèi fǎnjí zhàn de qíngkuàng jièshào" 珍宝岛自卫反击战的情况介绍, Zhànbèi jiàoyù cáiliào 战备教育材料, p. 3–5, 7–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Zhēnbǎo dǎo zìwèi fǎnjí zhàn de qíngkuàng jièshào" 珍宝岛自卫反击战的情况介绍, Zhànbèi jiàoyù cáiliào 战备教育材料, p. 3–5, 7–9.

- ^ Krivosheev, G. F. (2001). "Пограничные военные конфликты на Дальнем Востоке и в Казахстане (1969 г.)". Россия и СССР в войнах XX века: потери вооруженных сил : статистическое исследование. ISBN 978-5-224-01515-3. Archived from the original on 24 May 2007.

- ^ Kuzmina, N. (15 March 2010). "Как Виталий Бубенин спас Советский Союз от большого позора". SakhaNews. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "Некоторые малоизвестные эпизоды пограничного конфликта на о. Даманском". Военное оружие и армии Мира. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Goldstein 2003, p. 58.

- ^ Goldstein, p. 988, 990–995.

- ^ Gerson, Michael S. (2010) The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969 Archived 10 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Center for Naval Analyses, U.S.

- ^ Ryabushkin, Dmitri S. (2012). "New Documents on the Sino-Soviet Ussuri Border Clashes of 1969" (PDF). Eurasia Border Review. 3: 159–174 (163–64). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ RIA NOVOSTI (1 March 2004). "Veteran border guards mark 35th anniversary of Soviet-Chinese conflict". Sputnik. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Lai, Benjamin (20 November 2012). The Chinese People's Liberation Army since 1949: Ground Forces. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-78200-320-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lüthi 2012, p. 384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lüthi 2012, p. 385.

- ^ a b c d e f Lüthi 2012, p. 386.

- ^ Lüthi 2012, p. 388-389.

- ^ a b c d Lüthi 2012, p. 389.

- ^ a b c Lüthi 2012, p. 390.

- ^ (in Chinese) 在中苏边界对峙的日子里 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Xzmqzxc.home.news.cn. Retrieved on 3 February 2019.

- ^ 纪念铁列克提战斗40周年聚会活动联系启事 Archived 29 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Blog.sina.com.cn (6 May 2009). Retrieved on 2019-02-03.

- ^ Kuisong

- ^ a b c d e Lüthi 2012, p. 391.

- ^ Burr, William. "The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict, 1969 Archived 13 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine" National Security Archive, 12 June 2001.

- ^ "The President's Daily Brief" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 14 August 1969. pp. 3–4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "The President's Daily Brief" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. 13 August 1969. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Goldstein, p. 997.

- ^ Kuisong, p. 22.

- ^ The film features interviews with participants and leaders from both sides of the conflict.

- ^ Davydov, Grigori (20 March 2001). "Henry Kissinger plays ping-pong". Tabletennis.hobby.ru. Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "China, Russia solve all border disputes". Xinhua. 2 June 2005. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ "China, Russia complete border survey, determination". Xinhua. 21 July 2008. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Astashin, Nikita. "Новейшая фальсификация Китаем истории конфликта на острове Даманский и бездействие МИД России" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ Graviteam Tactics: Zhalanashkol 1969 on Steam Archived 15 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Store.steampowered.com (24 July 2014). Retrieved on 2019-02-03.

Cited sources

- Goldstein, Lyle J. (2001). "Return to Zhenbao Island: Who Started Shooting and Why it Matters". The China Quarterly. 168: 985–97. doi:10.1017/S0009443901000572.

- Goldstein, Lyle (Spring 2003). "Do Nascent WMD Arsenals Deter? The Sino-Soviet Crisis of 1969". Political Science Quarterly. 118 (1): 53–80. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2003.tb00386.x.

- Yang, Kuisong (2000). "The Sino-Soviet Border Clash of 1969: From Zhenbao Island to Sino-American Rapprochement". Cold War History. 1: 21–52. doi:10.1080/713999906.

- Lüthi, Lorenz (June 2012). "Restoring Chaos to History: Sino-Soviet-American Relations, 1969". The China Quarterly. 210: 378–398. doi:10.1017/S030574101200046X.

- Rea, Kenneth (September 1975). "Peking and the Brezhnev Doctrine". Asian Affairs. 3 (1): 22–30. doi:10.1080/00927678.1975.10554159.

External links

- Damansky Island Incident Part 1 (English Subtitles) YouTube

- Map showing some of the disputed areas

- Sino-Soviet Border Conflict, 1969

- How Comrade Mao was perceived in the Soviet Union

- The Sino-Soviet Border Conflict: Deterrence, Escalation, and the Threat of Nuclear War in 1969

- New Documents on the Sino-Soviet Ussuri Border Clashes of 1969

- Conflicts in 1969

- 1969 in China

- 1969 in the Soviet Union

- China–Soviet Union relations

- Cold War military history of the Soviet Union

- Cold War military history of China

- History of Manchuria

- History of the Russian Far East

- Wars involving the People's Republic of China

- Wars involving the Soviet Union

- Territorial disputes of China

- Territorial disputes of the Soviet Union

- China–Soviet Union border

- China–Russia border