Guru Ram Das

Guru Ram Das Sodhi | |

|---|---|

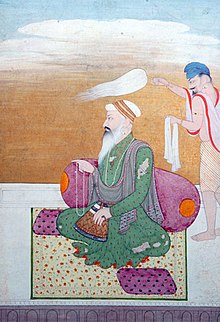

Opaque watercolour on paper c 1800 Government Museum, Chandigarh | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Bhai Jetha Mal Sodhi 24 September 1534[1] |

| Died | September 1, 1581 (aged 46) |

| Religion | Sikhism |

| Spouse | Bhani Rani |

| Children | Prithi Chand, Mahan Dev, and Guru Arjan |

| Parent(s) | Hari Das and Mata Daya |

| Known for | founder of Amritsar city[2] |

| Other names | The Fourth Guru |

| Occupation | Guru |

| Religious career | |

| Predecessor | Guru Amar Das |

| Successor | Guru Arjan |

| Part of a series on |

| Sikhism |

|---|

|

Guru Ram Das ([gʊɾuː ɾaːmᵊ d̯aːsᵊ]; 1534–1581) was the fourth of the ten Gurus of Sikhism.[2][3] He was born on 24 September 1534 in a family based in Lahore.[3][1] His birth name was Jetha, and he was orphaned at age 7; he thereafter grew up with his maternal grandmother in a village.[3]

At age 12, Bhai Jetha and his grandmother moved to Goindval, where they met Guru Amar Das.[3] The boy thereafter accepted Guru Amar Das as his mentor and served him. The daughter of Guru Amar Das married Bhai Jetha, and he thus became part of Guru Amar Das's family. As with the first two Gurus of Sikhism, Guru Amar Das instead of choosing his own sons, chose Bhai Jetha as his successor and renamed him as Ram Das or "servant or slave of god."[3][1][4]

Guru Ram Das became the Guru of Sikhism in 1574 and served as the Sikh leader until his death in 1581.[5] He faced hostilities from the sons of Amar Das, shifted his official base to lands identified by Amar Das as Guru-ka-Chak.[3] This newly founded town was eponymous Ramdaspur, later to evolve and get renamed as Amritsar – the holiest city of Sikhism.[6][7] He is also remembered in the Sikh tradition for expanding the manji organization for clerical appointments and donation collections to theologically and economically support the Sikh movement.[3] He appointed his own son as his successor, and unlike the first four Gurus who were not related through descent, the fifth through tenth Sikh Gurus were the direct descendants of Ram Das.[7][8]

Biography

Guru Ram Das was born in a Sodhi Khatri family in Chuna Mandi, Lahore. His father was Hari Das and mother Daya Kaur, both of whom died when he was aged seven. He was brought up by his grandmother.[1] He married Bibi Bhani, the younger daughter of Amar Das. They had three sons: Prithi Chand, Mahadev and Guru Arjan.[3]

Death and succession

Guru Ram Das died on 1 September 1581, in Goindval town of Punjab.[9]

Of his three sons, Ram Das chose Arjan, the youngest, to succeed him as the fifth Sikh Guru. The choice of successor led to disputes and internal divisions among the Sikhs.[7] The elder son of Ram Das named Prithi Chand is remembered in the Sikh tradition as vehemently opposing Arjan, creating a faction Sikh community which the Sikhs following Arjan called as Minas (literally, "scoundrels"), and is alleged to have attempted to assassinate young Hargobind.[10][11] However, alternate competing texts written by the Prithi Chand led Sikh faction offer a different story, contradict this explanation on Hargobind's life, and present the elder son of Ram Das as devoted to his younger brother Arjan. The competing texts do acknowledge disagreement and describe Prithi Chand as having become the Sahib Guru after the martyrdom of Guru Arjan Dev and disputing the succession of Guru Hargobind, the grandson of Ram Das.[12]

Influence

Amritsar

Guru Ram Das is credited with founding the holy city of Amritsar in the Sikh tradition.[6][7] Two versions of stories exist regarding the land where Ram Das settled. In one based on a Gazetteer record, the land was purchased with Sikh donations, for 700 rupees from the owners of the village of Tung.[1][13]

According to the Sikh historical records, the site was chosen by Guru Amar Das and called Guru Da Chakk, after he had asked Ram Das to find land to start a new town with a man made pool as its central point.[1][14][15] After his coronation in 1574, and the hostile opposition he faced from the sons of Amar Das,[3] Ram Das founded the town named after him as "Ramdaspur". He started by completing the pool, and building his new official Guru centre and home next to it. He invited merchants and artisans from other parts of India to settle into the new town with him.[1] The town expanded during the time of Arjan financed by donations and constructed by voluntary work. The town grew to become the city of Amritsar, and the pool area grew into a temple complex after his son built the gurdwara Harmandir Sahib, and installed the scripture of Sikhism inside the new temple in 1604.[7]

The construction activity between 1574 and 1604 is described in Mahima Prakash Vartak, a semi-historical Sikh hagiography text likely composed in 1741, and the earliest known document dealing with the lives of all the ten Gurus.[16]

Scripture hymns

Ram Das composed 638 hymns, or about ten percent of hymns in the Guru Granth Sahib. He was a celebrated poet, and composed his work in 30 ancient ragas of Indian classical music.[17]

These cover a range of topics:

One who calls himself to be a disciple of the Guru should rise before dawn and meditate on the Lord's Name. During the early hours, he should rise and bathe, cleansing his soul in a tank of nectar [water], while he repeats the Name the Guru has spoken to him. By this procedure he truly washes away the sins of his soul. – GGS 305 (partial)

The Name of God fills my heart with joy. My great fortune is to meditate on God's name. The miracle of God's name is attained through the perfect Guru, but only a rare soul walks in the light of the Guru's wisdom. – GGS 94 (partial)

O man! The poison of pride is killing you, blinding you to God. Your body, the colour of gold, has been scarred and discoloured by selfishness. Illusions of grandeur turn black, but the ego-maniac is attached to them. – GGS 776 (partial)— Guru Granth Sahib, Translated by G. S. Mansukhani[1]

His compositions continue to be sung daily in Harimandir Sahib (Golden temple) of Sikhism.[17]

Wedding hymn

Ram Das, along with Amar Das, are credited with various parts of the Anand and Laavan composition in Suhi mode. It is a part of the ritual of four clockwise circumambulation of the Sikh scripture by the bride and groom to solemnize the marriage in Sikh tradition.[17][18] This was intermittently used, and its use lapsed in late 18th century. However, sometime in 19th or 20th century by conflicting accounts, the composition of Ram Das came back in use along with Anand Karaj ceremony, replacing the Hindu ritual of circumambulation around the fire. The composition of Ram Das emerged to be one of the basis of British colonial era Anand Marriage Act of 1909.[18]

The wedding hymn was composed by Ram Das for his own daughter's wedding. The first stanza of the Laavan hymn by Ram Das refers to the duties of the householder's life to accept the Guru's word as guide, remember the Divine Name. The second verse and circle reminds the singular One is encountered everywhere and in the depths of the self. The third speaks of the Divine Love. The fourth reminds that the union of the two is the union of the individual with the Infinite.[19]

Masand system

While Guru Amar Das introduced the manji system of religious organization, Ram Das extended it with adding the masand institution. The masand were Sikh community leaders who lived far from the Guru, but acted to lead the distant congregations, their mutual interactions and collect revenue for Sikh activities and temple building.[3][20] This institutional organization famously helped grow Sikhism in the decades that followed, but became infamous in the era of later Gurus, for its corruption and its misuse in financing rival Sikh movements in times of succession disputes.[20][21]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h G.S. Mansukhani. "Ram Das, Guru (1534-1581)". Encyclopaedia of Sikhism. Punjab University Patiala. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ a b William Owen Cole; Piara Singh Sambhi (1995). The Sikhs: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-1-898723-13-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair (2013). Sikhism: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 38–40. ISBN 978-1-4411-5366-1.

- ^ Shakti Pawha Kaur Khalsa (1998). Kundalini Yoga: The Flow of Eternal Power. Penguin. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-399-52420-2.

- ^ Arvind-pal Singh Mandair (2013). Religion and the Specter of the West: Sikhism, India, Postcoloniality, and the Politics of Translation. Columbia University Press. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0-231-51980-9.

- ^ a b W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.

- ^ a b c d e Christopher Shackle; Arvind Mandair (2013). Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. Routledge. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-1-136-45101-0.

- ^ W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- ^ J. S. Grewal (2004). The Khalsa: Sikh and Non-Sikh Perspectives. Manohar. p. 207. ISBN 978-81-7304-580-6.

Guru Ram Das died in Goindval on 1 September 1581 to be succeeded by his youngest son.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- ^ W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- ^ Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- ^ Pardeep Singh Arshi (1989). The Golden Temple: history, art, and architecture. Harman. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-81-85151-25-0.

- ^ Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- ^ W.H. McLeod (1990). Textual Sources for the Study of Sikhism. University of Chicago Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-0-226-56085-4.

- ^ a b c Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 399–400. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ a b Louis E. Fenech; W. H. McLeod (2014). Historical Dictionary of Sikhism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-1-4422-3601-1.

- ^ Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84885-321-8.

- ^ a b Pashaura Singh; Louis E. Fenech (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ Madanjit Kaur (2007). Guru Gobind Singh: Historical and Ideological Perspective. Unistar. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-81-89899-55-4.