Women in Poland

| |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 5 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 28% (2017)[1] |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 79.4% (2012) |

| Women in labour force | 61.1% (employment rate OECD definition, 2019)[2] |

| Gender Inequality Index[3] | |

| Value | 0.139 (2013) |

| Rank | 26th out of 152 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[4] | |

| Value | 0.7031 (2013) |

| Rank | 54th |

The character of Polish women are shaped by its history, culture, and politics.[5] Poland has a long history of feminist activism, and was one of the first nations in Europe to enact women's suffrage. Poland is strongly influenced by the conservative social views of the Catholic Church.

History

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

|

The history of women on the territory of present-day Poland has many roots, and has been strongly influenced by Roman Catholicism in Poland. Feminism in Poland has a long history, and has traditionally been divided into seven periods, beginning arguably with the 18th century enlightenment, followed by first-wave feminism.[7] The first four early periods coincided with the foreign partitions of Poland, which resulted in the elimination of the sovereign Polish state for 123 years.[8]

1918-1939

Poland was among the first nations to grant women legal rights: women's suffrage was delivered in 1918,[9] after the country regained independence that year, following the 123-year period of partition and foreign rule. In 1932 Poland made marital rape illegal. Despite the improvement of the state's policies regarding women's rights, Polish women still faced discrimination on various levels. The interwar period was the time of forming of the "glass ceiling" concept in Polish society.[10] Women had to compete with men mainly for the well paid, high prestige positions.[10] Lower salary was primarily a result of the lower efficiency of the female employees in the physical labor but was later implemented in the other sectors where women were equally productive.[10]

Communism

During the communist era, women were ostensibly granted equal legal rights, and the official government rhetoric was one of supporting gender equality, but as in other communist states, the civil rights of both men and women were merely symbolic, as the system was an authoritarian one. Despite remaining de facto subordinated to male authority, women did see some gains under the communist régime, such as better access to education and to a more equal involvement in the workforce. Women's better situation during the communist era was significantly influenced by the socialist pro-birth position, seeking the increase in the population.[11] Pro-natalist policies were implemented by "generous maternity leave benefits and state contributions to child rearing".[11] After the martial law in Poland first publications discussing feminist ideas appeared in the public sphere, sometimes considered as the cover for the actual social situation.[10] Society mainly perceived feminism as the ideology alien to the Polish culture and mentality.[10] Communist leaders claimed that women in Poland obtained equal rights as the result of the socialistic social processes, and used that statement as the explanation for the lack and no need of feminism in Poland.[10] One of the Polish communists described a typical feminist as an "eccentric and aggressive witch, being anyway a lesbian, that would like to see a man go on all fours by her leg."[10]

Post-communism

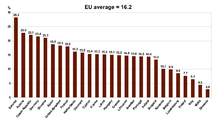

The fall of communism in Poland meant the shaking up of the politics and economy of the country, and initial economic and social destabilization. In the post-socialist workforce, women occupied mainly sectors of lower economic priority and light industries, due to factors such as selecting types of education and training more compatible with family life (usually paid less), discrimination and gender stereotypes.[12] This pattern of the gender employment inequality was viewed by majority as the result of the female's primary role in the family, as well as deeply rooted Polish culture and tradition of the patriarchal system.[12] The transition period was especially difficult for women, although men were also negatively affected. As of 2017, the employment rate for women aged 20–64 was 63.6%, compared to the men's rate of 78.2%.[13] Although Poland has an image of a conservative country, being often depicted as such in the Western media, Poland actually has high numbers of professional women, and women in business,[14] and it also has one of the lowest gender pay gaps in the European Union.[15] One of the obstacles faced by contemporary women in Poland is the anti-abortion law. Together with the "Polish Mother" myth perspective, banning of abortion is used to encourage women to have many children.[12][16] This ideology reinforces the view that women's place is in the home.[12] The Polish Mother symbol is a stereotype strongly stuck in the Polish consciousness and was shaped by the turbulent history of the nation.[16] During the long occupation time the responsibility for maintaining the national identity fell on the mothers, whose main task was the "upbringing of children".[16] Despite the strict legislation and the conservative political discourse, Poland has one of the lowest fertility rate in Europe.[17]

The status of women in contemporary Poland must be understood in the context of its political scene and of the role that the church plays in society. This is especially true withy regard to reproductive rights. Poland is a country strongly influenced by Roman Catholicism, and religion often shapes politics and social views. Law and Justice, abbreviated to PiS, is a national-conservative,[18][19] and Christian democratic[20][21] political party in Poland. With 237 seats in the Sejm and 66 in the Senate, it is currently the largest party in the Polish parliament.

Poland is part of the European Union (EU) since 2004. As such, it is subject to the EU directives. As part of the EU, Poland is socially influenced by 'Western' views, but there are regional differences between the western and the eastern parts of the country - "Poland A and B". Poland also has a significant rural population: about 40%,[22] which is deeply conservative.[23]

Old Polish customs

In old-time Poland customs of the people differed based on the social status. Polish customs derived from the other European traditions, however, they usually came to Poland later than in other countries.[24] The example of the chivalry illustrates the approach of the medieval class towards women. The entire idea of the chivalry was based on the almost divine worship of the female, and every knight had to have his "lady" ("dama") as the object of (very often platonic) love.[24] Knights felt obligated to take a patronage over their ladies.[24] Women in the old Poland were perceived as the soul of the company during the social gatherings.[24] In old Poland woman had a preeminent social position. Referring to girls as panny (ladies) which derives from the Polish word pan (sir) unlike chłopcy (boys) which comes from the word chłop (peasant) is the sign of respect shown towards women.[24] Long time before emancipation movements women in Poland made their social role very important, mainly due to th numerous conflicts and threats that kept man out of homes.[24] Political and economic situation required women to become self-sufficient and valiant.[24] Different from the modern times were also outfits of the Polish women. The mid-XVI century' apparels contained diverse types of decorations and accessories.[24] Women's headwear included decorative wreaths, veils, and various hatbands. Among the notable elements of the old-time outfit were "long, satin dresses" decorated with the gold and pearls, as well as the "aureate slippers".[24]

Women in sports

Polish women have earned a special place in the country's sports. The top 3 place for the most wins in the annual most popular sportsperson contest, the Plebiscite of Przegląd Sportowy, are occupied by women. Among the most prominent Polish women athletes are Justyna Kowalczyk, Irena Szewińska and Stanisława Walasiewicz. In the 2016 Rio Summer Olympics Poland was represented by 101 women athletes. They won 8 out of 11 medals for Poland, including two gold medals.

Notable women in Polish history

The important women in Poland's early history include: Swietoslava (sometimes confused as being Sigrid the Haughty or Gunhilda; also known as Storrada), the daughter of Mieszko the First and Dobrawa of Bohemia; Katarzyna Jagiellonka (also known as Catherine Jagiello or Katarrina Jegellonica); Dobrawa herself (wife of Mieszko the First), the daughter of the Duke of Bohemia; Jadwiga (Hedwig), the daughter of a Hungarian king.[25] During the Enlightenment, two women stand out: Barbara Sanguszko, hostess, writer and philanthropist and her granddaughter, Tekla Teresa Lubienska, writer and mother of a magnate dynasty. Emilia Plater was an early revolutionary associated with the November Uprising. In music, the composer and pianist, Maria Szymanowska won acclaim from St-Petersburg to London. Marie Sklodowska was a Nobel Prize winning scientist who moved to France in the late 19th-c. Many notable women contributed to Poland's independence movement at the dawn of the 20th-c. These included, the activist and military officers, Aleksandra Zagórska and the mostly forgotten, Wanda Gertz as well as Anna Walentynowicz, co-founder of the anti-communistic "Solidarity" ("Solidarność"). Wisława Szymborska was a Polish poet, recipient of the Nobel Prize in 1996.

Gallery

-

A group of girls in rural Poland, 1959

-

Two teenage girls in contemporary Poland

-

Justyna Kowalczyk (Olympic champion)

References

Specific

- ^ https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SG.GEN.PARL.ZS

- ^ http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R#

- ^ "Table 4: Gender Inequality Index". United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "The Global Gender Gap Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum. pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Polish women". polishmarriage.org. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ European Commission. The situation in the EU. Retrieved on July 12, 2011.

- ^ Łoch, Eugenia (ed.) 2001. Modernizm i feminizm. Postacie kobiece w literaturze polskiej i obcej. Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu M.Curie-Skłodowskiej, p.44

- ^ Davies, Norman. God's Playground: a history of Poland. Revised Edition. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005.

- ^ https://www.britannica.com/topic/woman-suffrage

- ^ a b c d e f g Natalia., Krzyżanowska. Kobiety w (polskiej) sferze publicznej. Toruń. ISBN 9788377801628. OCLC 830511460.

- ^ a b Fodor, Eva; Glass, Christy; Kawachi, Janette; Popescu, Livia (2002–2012). "Family policies and gender in Hungary, Poland, and Romania". Communist and Post-Communist Studies. 35 (4): 475–490. doi:10.1016/s0967-067x(02)00030-2. ISSN 0967-067X.

- ^ a b c d Łobodzińska, Barbara (2000–2001). "Polish women's gender-segregated education and employment". Women's Studies International Forum. 23 (1): 49–71. doi:10.1016/s0277-5395(99)00090-4. ISSN 0277-5395.

- ^ https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/refreshTableAction.do?tab=table&plugin=1&pcode=t2020_10&language=en

- ^ http://www.grantthornton.global/en/press/press-releases-2015/women-in-business-2015/

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/justice/gender-equality/gender-pay-gap/situation-europe/index_en.htm

- ^ a b c Imbierowicz, Agnieszka (1 June 2012). "The Polish Mother on the Defensive? The Transformation of the Myth and Its Impact on the Motherhood of Polish Women". Journal of Education Culture and Society. 2012 (1): 140–153. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- ^ http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tps00199&plugin=1

- ^ Hloušek, Vít; Kopeček, Lubomír (2010), Origin, Ideology and Transformation of Political Parties: East-Central and Western Europe Compared, Ashgate, p. 196

- ^ Nodsieck, Wolfram, "Poland", Parties and Elections in Europe, retrieved 28 March 2012

- ^ Dominik Hierlemann, ed. (2005). Lobbying der katholischen Kirche: Das Einflussnetz des Klerus in Polen. Springer-Verlag. p. 131. ISBN 978-3531146607.

- ^ "Unentschlossene als Zünglein an der Waage". News ORF. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ^ https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2212.html

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/25/law-and-justice-poland-drift-to-right

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kosinski, Waclaw (1921). Zwyczaje towarzyskie w dawnej Polsce. Sandomierz. hdl:2027/uc1.b5106109.

- ^ "Women in Poland's Early History". Retrieved 2 November 2013.

General

- Lewis, Jone Johnson. Poland - Women, Encyclopedia of Women's History.