Afyonkarahisar

Afyonkarahisar | |

|---|---|

A view from the Cumhuriyet Square and Utku Monument in Afyonkarahisar | |

| Coordinates: 38°45.48′N 30°32.32′E / 38.75800°N 30.53867°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Aegean |

| Province | Afyonkarahisar |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Burhanettin Çoban (AKP) |

| • Governor | Aziz Yıldırım |

| Area | |

| • District | 1,025.14 km2 (395.81 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,021 m (3,350 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Urban | Template:Turkey district populations |

| • District | Template:Turkey district populations |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (FET) |

| Postal code | 03xxx |

| Licence plate | 03 |

| Website | www.afyon-bld.gov.tr |

Afyonkarahisar (Turkish pronunciation: [afjonkaɾahiˈsaɾ], Template:Lang-tr "poppy, opium", kara "black", hisar "fortress"[2]) is a city in western Turkey, the capital of Afyon Province. Afyon is in mountainous countryside inland from the Aegean coast, 250 km (155 mi) south-west of Ankara along the Akarçay River. Elevation 1,021 m (3,350 ft). Population (2010 census) 173,100 [3] In Turkey, Afyonkarahisar stands out as a capital city of thermal and spa,[4] an important junction of railway, highway and air traffic in West-Turkey,[5] and the grounds where independence had been won.[6] In addition, Afyonkarahisar is one of the top leading provinces in agriculture,[7] globally renowned for its marble[8] and globally largest producer of pharmaceutical opium.[9]

Etymology

The name Afyon Kara Hisar (literally opium black castle in Turkish), since opium was widely grown here and there is a castle on a black rock.[citation needed] Also known simply as Afyon. Older spellings include Karahisar-i Sahip, Afium-Kara-hissar and Afyon Karahisar. The city was known as Afyon (opium), until the name was changed to Afyonkarahisar by the Turkish Parliament in 2004.

History

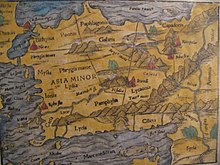

The top of the rock in Afyon has been fortified for a long time. It was known to the Hittites as Hapanuwa, and was later occupied by Phrygians, Lydians and Achaemenid Persians until it was conquered by Alexander the Great. After the death of Alexander the city (now known as Akroinοn (Ακροϊνόν) or Nikopolis (Νικόπολις) in Ancient Greek), was ruled by the Seleucids and the kings of Pergamon, then Rome and Byzantium. The Byzantine emperor Leo III after his victory over Arab besiegers in 740 renamed the city Nicopolis (Greek for "city of victory"). The Seljuq Turks then arrived in 1071 and changed its name to Kara Hissar ("black castle") after the ancient fortress situated upon a volcanic rock 201 meters above the town. Following the dispersal of the Seljuqs the town was occupied by the Sâhib Ata and then the Germiyanids.

The castle was much fought over during the Crusades and was finally conquered by the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid I in 1392 but was lost after the invasion of Timur Lenk in 1402. It was recaptured in 1428 or 1429.

The area thrived during the Ottoman Empire, as the centre of opium production and Afyon became a wealthy city. In 1902, a fire burning for 32 hours destroyed parts of the city.[10]

During the 1st World War British prisoners of war who had been captured at Gallipoli were housed here in an empty Armenian church at the foot of the rock. During the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) campaign (part of the Turkish War of Independence) Afyon and the surrounding hills were occupied by Greek forces. However, it was recovered on 27 August 1922, a key moment in the Turkish counter-attack in the Aegean region. After 1923 Afyon became a part of the Republic of Turkey.

The region was a major producer of raw opium (hence the name Afyon) until the late 1960s when under international pressure, from the USA in particular, the fields were burnt and production ceased. Now poppies are grown under a strict licensing regime. They do not produce raw opium any more but derive Morphine and other opiates using the poppy straw method of extraction.[11]

Afyon was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 50 lira banknote of 1927-1938.[12]

Economy

The economy of Afyonkarahisar is based on agriculture, industries and thermal tourism. Especially its agriculture is strongly developed from the fact, a large part of its population living in the countrysides. Which stimulated agricultural activities greatly.

Marble

Afyonkarahisar produces an important chunk of Turkish processed marbles, it ranks second on processed marble exports and fourth on travertine.[13][14] Afyon holds an important share of Turkish marble reserves, with some 12,2% of total Turkish reserves.[15][16]

Afyon has unique marble types and colors, which were historically very renown and are unique to Afyon. Like "Afyon white", historically known as "Synnadic white". "Afyon Menekse", historically known as "Pavonazzetto"[17] and "Afyon kaplan postu", this type wasn't popular. Historically marble from Afyon was generally referred to as "Docimeaen marble".[18] Docimian marble was highly admired and valued for its unique colors and fine grained quality, by ancients such as Romans.[19] When the Romans took control over Docimian quarries, they were blown away about the beautiful color combinations of Docimian Pavonazzetto, which is a type of white marble with purple veins. A trend started about it right away. Emperors Augustus, Trajan, Hadrian, all made extensive use of Docimian marble to all their major building projects.[20][21]

Docimian Pavonazzetto was extensively used in major building projects in the very heart of Rome aka Forum Romanum and all over the empire. Pavonazzetto was used on the most eye catching places such as, columns, wall and floor veneer and wall reliefs. Other marbles from all corners of the empire were used in combination, whenever Pavonazzetto was used as floor cover, it was usually in combination with other decorative marbles. But, the Pavonazzetto being a white marble was mostly the dominant color and gave the buildings a freshening white color.

One of the greatest Roman architectural piece, the Pantheon contains Docimian Pavonazzetto as floor pavement along with other marble types.[22][23] The dominant white color is the Pavonazzetto, also some of the interior main columns and pilasters are made from Docimian marble.[24] Other buildings in Roman capital which contains or contained Docimian marble were, Forum of Augustus,[25] Forum of Trajan (floor and 184 column shafts),[26][27][28] Temple of Mars Ultor (floor),[29] Temple of Apollo (floor),[30] Basilica Aemelia (20 statues),[31][32] Basilica Julia (floor and some columns),[33][34] Basilica Ulpia (some of the columns),[35] Basilica San Paolo Fuori Le Mura (24 columns, destroyed by fire in 1823),[36] The eight statues on the Arch of Constantine,[37] The greatest Roman bath, Baths of Caracalla (some of the columns and wall veneer.[38][39]

Other major buildings outside Italy, Rome were :

The Hagia Sophia, one of the greatest buildings ever built, has Docimian marble as veneer on the aisles and galleries.[40]

The heart of Catholic Christianity, Saint Peter's Basilica, as veneer.[41]

Lepcis Magna, former limestone columns were replaced with Pavonazzetto.[42]

Library of Celsus, the columns on the famous wall.[43]

Ancient City of Sagalassos, as wall and floor covering, 40 tons of veneer were recovered.[44][45]

Temple of Zeus and Hera in Greece, 100 columns and wall.[46]

Docimian marble was also preferred for sarcophagi sculpting, some emperors preferred this marble for its high value and majestic looks. As a result, one of the greatest masterpieces were made from this material. Such as sarcophagus of, Sidamara, Silifkeh, Seleukeia, Eudocia, Heraclius....several hundreds sarcophagi were constructed.[47]

Thermal sector

The geography of Afyon has great geothermal activity. Hence, the place has plenty thermal springs, there are about 5 main springs. Each of them have high mineral contents and high degree's, 40 °C-100 °C. The waters have strong healing properties to some diseases. As a result, plenty of thermals commenced over time.

In time Afyon has developed it's thermal sector with more capacity, comfort and innovation. Afyon combined the traditional bath houses with 5 star resorts, the health benefits of the natural springs have put the thermal resorts further then a mere attraction. Hospitals and universities have come in association with thermal resorts, to utilize the full health potentials of the thermals. As such, Kocatepe University Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Hospital opened for that purpose.[48] Afyon now has the largest residence capacity of thermal resorts,[49][4] of which a large part are 5 star thermal hotels which give medical care with qualified personnel.

Spa water

Kizilay, was the first mineral water factory in Turkey which opened in Afyon, in 1926 by Atatürk. After the mineral water from Gazligöl springs, healed Ataturks kidneys and proved its health benefits. Since its foundation, "Kizilay Spa Water" grew as the biggest spa water distributor in Turkey, Middle-East and Balkans.[50][51]

Pharmaceuticals and morphine

Almost a third of all the morphine produced in the world derives from alkaloids factory in Afyon, named as "Afyon Alkaloids". this large capacity is the byproduct of Afyon's poppy plantations. The pharmaceuticals derive from the opium of the poppy capsules. "Afyon Alkaloids" factory is the largest of its kind in the world,[9][52] with high capacity processing ability and modern laboratories. The raw opium is put through a chain of biochemical processes, resulting into several types of morphine.

In the Alkaloid Extraction Unit only base morphine is produced. In the adjacent Derivatives Unit half of the morphine extracted is converted to morphine hydrochloride, codeine, codeine phosphate, codeine sulphate, codeine hydrochloride, morphine sulphate, ethylmorphine hydrochloride.[53]

Agriculture

Livestocks Afyon breeds a large amount of livestocks, its landscape and demography is suitable for this field. As such it ranks in the top 10 within Turkey in terms of amounts of sheep and cattle it has.[54]

Meat and meat products As a result of being an important source of livestock, related sectors such as meat and meat products are also very productive in afyon. Its one of the leading provinces in red meat production[55][56][57] and has very prestigious brand marks of sausages, such as "Cumhuriyet Sausages".[58]

Eggs Afyon is the sole leader in egg production within Turkey. It has the largest amount of laying hens, with a figure of 12,7 million.[59] And produces a record amount of 6 million eggs per day.[60]

Cherries and sour cherries Sour cherries are cultivated in Afyon in very large numbers, so much so that it became very iconic to Afyon. Every year, a sour cherry festival takes place in the Cay district. It is the largest producer of sour cherries in Turkey.[61] The sour cherries grown in Afyon are of excellent quality because of the ideal climate they're grown in. For the same reason Afyon is also an ideal place for cherry cultivation. First quality cherries known as "Napolyon Cherries" are grown in abundance, its one of the top 5 leading provinces.[62]

Poppy One of the iconic agricultural practices of Afyon is the cultivation of poppy. Afyon's climate is ideal for the cultivation of this plant, hence a large amount of poppy plantation occurs in this region. Though, a strong limitation came some decades ago from international laws, cause of the opium content of poppy plants peels. Nevertheless, Afyon is the largest producer of poppy in Turkey[61] and accounts for a large amount of global production.

Potatoes and sugar-beets Afyon has a durable reputation in potato production, it produces around 8% of Turkish potato need. It ranks in the top 5 in potato, sugar-beets, cucumber and barley production.[61]

Climate

Afyonkarahisar has a hot and dry summer continental climate (Dsa) under the Köppen classification and a hot summer continental (Dca) or hot summer oceanic climate (Doa) under the Trewartha classification. The winters are cold and snowy winters and the summers are hot and dry with cool nights. Rainfall occurs mostly during the spring and autumn.

| Climate data for Afyonkarahisar (1950 - 2014) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.4 (63.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

30.2 (86.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

35.8 (96.4) |

39.8 (103.6) |

38.2 (100.8) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

24.5 (76.1) |

21.0 (69.8) |

39.8 (103.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

6.5 (43.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

21.1 (70.0) |

25.6 (78.1) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.4 (32.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.4 (41.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

15.0 (59.0) |

19.1 (66.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

17.7 (63.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

2.5 (36.5) |

11.3 (52.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −3.4 (25.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

0.2 (32.4) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.7 (56.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.9 (42.6) |

1.7 (35.1) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

5.2 (41.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −27.0 (−16.6) |

−25.3 (−13.5) |

−17.0 (1.4) |

−7.6 (18.3) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

4.0 (39.2) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−14.9 (5.2) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−27.0 (−16.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 42.2 (1.66) |

37.7 (1.48) |

43.7 (1.72) |

46.3 (1.82) |

51.6 (2.03) |

35.1 (1.38) |

19.4 (0.76) |

11.2 (0.44) |

19.7 (0.78) |

37.5 (1.48) |

32.9 (1.30) |

45.3 (1.78) |

422.6 (16.63) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.6 | 11.9 | 12.5 | 11.9 | 12.1 | 7.5 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 7.6 | 8.8 | 12.6 | 108.8 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 3.0 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 8.2 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 10.6 | 8.5 | 6.3 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 6.7 |

| Source: Turkish State Meteorological Service[63] | |||||||||||||

Afyon today

Afyon is the centre of an agricultural area and the city has a country town feel to it. There is little in the way of bars, cafes, live music or other cultural amenities, and the standards of education are low for a city in the west of Turkey. However Afyon Kocatepe University opened in the 1990s and this must surely lead to improvements eventually. Nowadays Afyon is known for its marble (in 2005 there were 355 marble quarries in the province of Afyon producing high quality white stone), its sucuk (spiced sausages), its kaymak (meaning either cream or a white Turkish Delight) and various handmade weavings. There is also a large cement factory.

This is a natural crossroads, the routes from Ankara to İzmir and from Istanbul to Antalya intersect here and Afyon is a popular stopping-place on these journeys. There are a number of well-established roadside restaurants for travellers to breakfast on the local cuisine. Some of these places are modern well-equipped hotels and spas; the mineral waters of Afyon are renowned for their healing qualities. There is also a long string of roadside kiosks selling the local Turkish delight.

Transport

Afyon is also an important rail junction between İzmir, Konya, Ankara and Istanbul. Afyon is on the route of the planned high-speed rail line between Ankara and Izmir.

See also: Afyon Ali Çetinkaya railway station, Afyon City railway station

Cuisine

Courses

- sucuk - the famed local speciality, a spicy beef sausage, eaten fried or grilled. The best known brands include Cumhuriyet, Ahmet İpek, İkbal, İtimat

.

Sweets

- local cream kaymak eaten with honey, with a bread pudding ekmek kadayıf, or with pumpkin simmered in syrup. Best eaten at the famous Ikbal restaurants (either the old one in the town centre or the big place on the main road).

- Turkish delight.

- helva - sweetened ground sesame

Main sights

- Afyonkarahisar Castle

- Victory Museum (Zafer Müzesi), a national military and war museum, which was used as headquarters by then Commander-in-Chief Mustafa Kemal Pasha (Atatürk), his chief general staff and army commanders before the Great Offensive in August 1922.[64] In the very city center, across the fortress, featuring maps, uniforms, photos, guns from the Greco-Turkish War.

- The partly ruined fortress which has given the city its name. To reach at the top, eight hundred stairs need to be climbed.

- The Afyonkarahisar Archaeological Museum which houses thousands of Hellenic, Frigian, Hittite, Roman, Ottoman finds.

- Ulu Camii (the Great Mosque)

- Altıgöz Bridge, like the Ulu Camii built by the Seljuqs in the 13th century.

- Afyon mansion (Afyon konagi) situated on a hill overlooking the panoramic plain.

- the White Elephant - Afyon is twinned with the town of Hamm in Germany, and now has a large statue of Hamm's symbolic white elephant.

With its rich architectural heritage, the city is a member of the European Association of Historic Towns and Regions [1].

| Year | 1914 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 |

| Population | 285,750[65] | 95,643 | 103,000 | 128,516 |

Twin towns – sister cities

Notable natives

Following list is alphabetically sorted after family name.

- Mihran Mesrobian (1889-1975), architect and decorated Ottoman soldier

- İlker Başbuğ (1943), former Chief of the General Staff of Turkey

- Ali Çetinkaya (1879-1949), Ottoman Army officer and Turkish politician

- Fikret Emek (1963), retired military personnel of the Special Forces Command

- Veysel Eroğlu (1948), Minister of Environment and Forestry

- Bülent İplikçioğlu (1952), historian

- Fazıl Şenel (1972), High Commissioner / Board Member of EMRA (EPDK), Ex-President of BOTAŞ

- Ahmed Karahisari (1468- 1566), Ottoman calligrapher

- Gülcan Mıngır (1989), European Champion Middle distance runner

- Ahmet Necdet Sezer (1941), former President of Turkey

- Sibel Özkan Öz (1988), Olympic medalist female weightlifter

- Nurgül Yeşilçay (1976), actress

See also

References

- ^ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ Lewis Thomas (Apr 1, 1986). Elementary Turkish. Courier Dover Publications. p. 12. ISBN 978-0486250649.

- ^ Statistical Institute[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Evren Ekiz (2016). termal turizmde farkli bir destinasyon: jeoturizm (afyonkarahisar örnegi) (PDF). p. 70.

- ^ "Afyonkarahisar - Turkey". britannica.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Rosie Ayliffe (2003). TURKEY. p. 606.

- ^ "The project created in Afyon, thermal greenhouse out of 660 thousand square meters". www.habermonitor.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Erica Highes (2013). Meaning and λόγος: Proceedings from the Early Professional Interdisciplinary. University of Liverpool. p. 29.

- ^ a b US Department for State Bureau. International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. p. 388.

- ^ "Latest intelligence - Turkish town burnt". The Times. No. 36861. London. 1 September 1902. p. 4. template uses deprecated parameter(s) (help)

- ^ https://fco-stage.fco.gov.uk/resources/en/pdf/pdf20/fco_adidu_licitcultivation[permanent dead link]

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 2009-06-03 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 1. Emission Group - Fifty Turkish Lira - I. Series Archived March 5, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. – Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- ^ Belkıs ÖZKAR. mermer sektöründe katma degerin ve ihracatin artirilmasi (PDF). p. 29.

- ^ Dilsad Erkek. Mermer ve Traverten Sektörüne Küresel ve Bölgesel Yaklaşım (PDF). p. 25.

- ^ Sevgi Gürcan. Türkiye ve Afyon'da mermer sektörünün gelisim trendi, Kocatepe University (PDF). p. 389.

- ^ Nuran Tasligil. Die Analyse der als Baumaterial genutzten, Marmara University. p. 619.

- ^ Barbara E. Borg (2015). A Companion to Roman Art. p. 157.

- ^ Strabo. Geography. "Book 9, chapter 5, section 16"

- ^ Donato Attanasio (2003). Ancient White Marbles. p. 154.

- ^ Donato Attanasio (2003). Ancient White Marbles. p. 157.

- ^ Strabo. Geography. Book 12, 8, 14

- ^ Anthony Grafton (2010). Classical Tradition, Harvard University. p. 842.

- ^ William Lloyd Macdonald (2002). The Pantheon, Harvard University. p. 86.

- ^ J. Clayton Fant (1989). Cavum Antrum Phrygia. p. 8.

- ^ Kathleen S.Lamp (2013). A City of Marble, University of South Carolina.

- ^ Gaynor Aaltonen (2008). The History of Architecture.chapter, ROME: CROSSING CONTINENTS

- ^ James E. Packer (2001). The Forum of Trajan in Rome. p. 120.

- ^ Ben Russell (2013). The Economics of Roman Stone Trade, Oxford University. p. 229.

- ^ John W. Stamper (2005). The Architecture of Roman Temples, Cambridge University. p. 137.

- ^ John W. Stamper (2005). The Architecture of Roman Temples, Cambridge University. p. 136.

- ^ Max Schvoerer (1999). ASMOSIA 4, University of Bordeaux. p. 278.

- ^ Gilbert J. Gorski (2015). The Roman Forum, Cambridge University. p. 19.

- ^ Gregor Kalas (2015). Restoration of The Roman Forum in Late Antiquity, University of Texas. p. 43.

- ^ J. Clayton Fant (1989). Cavum antrum Phrygia. p. 8.

- ^ L. Richardson (1992). A New Topographical Dictionnary of Ancient Rome, The Johns Hopkins University. p. 176.

- ^ Lawrence Nees (2015). Perspective on Early Islamic Art in Jerusalem. p. 107.

- ^ The Economics of the Roman Stone Trade, Oxford University. 2014. p. 324.

- ^ Janet DeLaine (1997). The Baths of Caracalla. p. 32,70.

- ^ Dante Giuliano Bartoli (2008). Marble Transport in the Time of the Severans, Texas University (PDF). p. 154.

- ^ Nadine Schibille (2014). Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Aesthetic Experience, University of Sussex. pp. 241–242.

- ^ Keith Miller (2011). St. Peter's, Harvard University. p. 110.

- ^ Ben Russell (2014). The Economic of the Roman Stone Trade, Oxford University. p. 28.

- ^ Barbara E. Borg (2015). A Companion to Roman Art. p. 124.

- ^ Abu Jaber; N. Bloxam. QuarryScapes, Geological Survey of Norway (PDF). p. 102.

- ^ Marc Waelkens (2000). Sagalassos Five, Leuven University. p. 339.

- ^ Pausanias. Book 1 Attica 16-29, Athens. Book, 1,18,9

- ^ Donato Attanasio; Mauro Brilli (2006). The Isotopic Signature of Classical Marbles. p. 151.

- ^ Kurtulus Karamustafa; ömer Sanlioglu; Kenan Gülle (2013). Ulusal Turizm Kongresi, Erciyes University. pp. 245–246.

- ^ Prof.Ergün Türker; Ahmet Yildiz (2008). Termal ve Maden Sulari Konferansi, Afyon University (PDF). p. iX.

- ^ Şafak, Yeni (17 August 2015). "Kızılay maden suyu 17 ülkeye satılıyor". Yeni Şafak. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Kizilay

- ^ plantation Office Archived October 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zohara Yaniv; Nativ Dudai (2014). Medical and Aromatic Plants of the Middle-East. Institute of Plant Sciences. p. 328.

- ^ (TÜİK), Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu. "Türkiye İstatistik Kurumu, Hayvansal Üretim İstatistikleri, Haziran 2015". www.tuik.gov.tr. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Et fiyatları artık Afyon'da belirlenecek - Son Dakika Ekonomi Haberleri - STAR". star.com.tr. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ YABANTV. "Tarımda Afyon Modeli!". yabantv.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "'Fiyat istikrarı için et sınıflandırılmalı' - Memurlar.Net". www.memurlar.net. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ "Afyonkarahisar Where the old world meets the new". dailysabah.com. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ foundation of egg producers (2015). Yumurta Tavukculugu verileri (PDF). p. 4.

- ^ "Company Profile". www.afyonyumurta.com.tr. Archived from the original on 2018-04-09. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Afyonkarahisar'in sosyo-ekonomik göstergeleri (PDF). 2014. p. 60.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Foundation of Turkish Agriculture Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Meteoroloji" (in Turkish). Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ "Müzeler-Zafer Müzesi (Başkomutan Tarihi Milli Park Müdürlüğü)" (in Turkish). Ayfonkarahisar İl Kültür ve Turizm Müdürlüğü. Retrieved 2015-08-10.

- ^ Stanford, Jay Shaw (1976). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University. pp. 239–241. ISBN 9780521291668.

External links

- Afyon Karahisar Template:Tr icon

- City council website Template:Tr icon

- Governor's office

- Afyonkarahisar community and information

- Afyon Blog Template:En icon and Template:Tr icon

- Afyonkarahisar City Daily Photo Template:En icon and Template:Tr icon

- Afyon Guide and Photo Album Template:En icon

- Afyon and the Phrygians Template:En icon

- Afyon Kocatepe University Template:En icon

- Department of forestry and the environment Template:Tr icon

- Afyon Science High School Template:Tr icon* * Afyon Zafer College Template:Tr icon