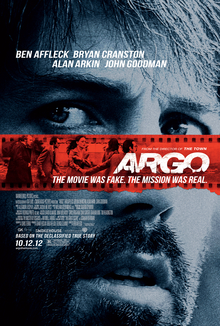

Argo (2012 film)

| Argo | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ben Affleck |

| Screenplay by | Chris Terrio |

| Produced by | Grant Heslov Ben Affleck George Clooney |

| Starring | Ben Affleck Bryan Cranston Alan Arkin John Goodman |

| Cinematography | Rodrigo Prieto |

| Edited by | William Goldenberg |

| Music by | Alexandre Desplat |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 120 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English & Persian |

| Budget | $44.5 million[2] |

| Box office | $206,753,502[2] |

Argo is a 2012 American fictionalized thriller film directed by Ben Affleck. This dramatization is adapted from the book The Master of Disguise by CIA operative Tony Mendez, and Joshuah Berman's 2007 Wired article "The Great Escape" about the "Canadian Caper",[3] in which Mendez led the rescue of six U.S. diplomats from Tehran, Iran, during the 1979 Iran hostage crisis.[4]

The film stars Affleck as Mendez with Bryan Cranston, Alan Arkin, and John Goodman, and was released in North America to critical and commercial success on October 12, 2012. The film was produced by Grant Heslov, Ben Affleck, and George Clooney. The story of this rescue was also told in the 1981 television movie Escape from Iran: The Canadian Caper, directed by Lamont Johnson.[5][6]

Argo received seven nominations for the 85th Academy Awards and won three, for Best Film Editing,[7] Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Picture, the first time since 1989's Driving Miss Daisy where the Best Picture winner was not nominated for Best Director. The film also earned five Golden Globe nominations, winning Best Picture – Drama and Best Director, while being nominated for Best Supporting Actor for Arkin. It won the award for the Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture at the 19th Screen Actors Guild Awards with Alan Arkin being nominated for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role. It also won Best Film, Best Editing, and Best Director (for Affleck) at the 66th British Academy Film Awards.

Plot

Militants storm the United States embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979, in retaliation for CIA involvements in Iran. More than 50 of the embassy staff are taken as hostages, but six escape and hide in the home of the Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor (Victor Garber). With the escapees' situation kept secret, the US State Department begins to explore options for "exfiltrating" them from Iran. Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck), a CIA exfiltration specialist brought in for consultation, criticizes the proposals. He too is at a loss for an alternative until, inspired by watching Battle for the Planet of the Apes on the phone with his son, he plans to create a cover story that the escapees are Canadian filmmakers, scouting "exotic" locations in Iran for a similar science-fiction film.

Mendez and his supervisor Jack O'Donnell (Bryan Cranston) contact John Chambers (John Goodman), a Hollywood make-up artist who has previously crafted disguises for the CIA. Chambers puts them in touch with film producer Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin). Together they set up a phony film studio, publicize their plans, and successfully establish the pretense of developing Argo, a "science fantasy" in the style of Star Wars, to lend credibility to the cover story. Meanwhile, the escapees grow frantic inside the ambassador's residence. The revolutionaries reassemble embassy papers shredded before the takeover and learn that some personnel have escaped.

Posing as a producer for Argo, Mendez enters Iran and links up with the six escapees. He provides them with Canadian passports and fake identities to prepare them to get through security at the airport. Although afraid to trust Mendez's scheme, they reluctantly go along with it, knowing that he is risking his own life too. A "scouting" visit to the bazaar to maintain their cover story takes a bad turn, but their Iranian culture contact gets them away from the hostile crowd.

Mendez is told that the operation has been cancelled to avoid conflicting with a planned military rescue of the hostages. He pushes ahead, forcing O'Donnell to hastily re-obtain authorization for the mission to get tickets on a Swissair flight. Tension rises at the airport, where the escapees' flight reservations are confirmed at the last minute, and a guard's call to the supposed studio in Hollywood is answered at the last second. The group boards the plane just as the Iranian guards uncover the ruse and try to stop their plane from getting off the runway, but they are too late, as Mendez and the six successfully leave Iran.

To protect the hostages remaining in Tehran from retaliation, all US involvement in the rescue is suppressed, giving full credit to the Canadian government and its ambassador (who left Iran with his wife under their own credentials as the operation was underway; their Iranian housekeeper, who had known about the Americans and lied to the revolutionaries to protect them, escaped to Iraq). Mendez is awarded the Intelligence Star, but due to the classified nature of the mission, he would not be able to keep the medal until the details were made public in 1997. All the hostages were freed on January 20, 1981. The film ends with President Carter's speech about the Crisis and the Canadian Caper.

Cast

- Ben Affleck as Tony Mendez

- Bryan Cranston as Jack O'Donnell

- Alan Arkin as Lester Siegel

- John Goodman as John Chambers

- Tate Donovan as Robert Anders

- Clea DuVall as Cora Lijek

- Christopher Denham as Mark Lijek

- Scoot McNairy as Joe Stafford

- Kerry Bishé as Kathy Stafford

- Rory Cochrane as Lee Schatz

- Victor Garber as Ken Taylor

- Kyle Chandler as Hamilton Jordan

- Chris Messina as Malinov

- Željko Ivanek as Robert Pender

- Titus Welliver as Jon Bates

- Bob Gunton as Cyrus Vance (United States Secretary of State)

- Philip Baker Hall as Stansfield Turner (Director of Central Intelligence) (Uncredited)

- Richard Kind as Max Klein

- Richard Dillane as Peter Nicholls

- Michael Parks as Jack Kirby

- Tom Lenk as Rodd

- Christopher Stanley as Tom Ahern

- Page Leong as Pat Taylor

- Taylor Schilling as Christine Mendez

- Ashley Wood as Beauty

- Sheila Vand as Sahar

- Devansh Mehta as Matt Sanders

- Omid Abtahi as Reza

- Karina Logue as Elizabeth Ann Swift

- Adrienne Barbeau as Nina

- Fouad Hajji as Komiteh

Affleck cast Goodman, Parks and Bishé after seeing them in Red State.

Production

Filming

Argo is based on the Canadian Caper that took place during the Iran hostage crisis in 1979 and 1980. Chris Terrio wrote the screenplay based on Joshuah Bearman's 2007 article in Wired: "How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran".[3] The article was written after the records were declassified.

In 2007, the producers George Clooney, Grant Heslov and David Klawans set up a project based on the article. Affleck's participation was announced in February 2011.[8] The following June, Alan Arkin was the first person cast in the film.[9] After the rest of the roles were cast, filming began in Los Angeles[10] in August 2011. Additional filming took place in McLean, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and Istanbul.[11]

As a historical piece, the film made use of archival news footage from ABC, CBS and NBC; and included popular songs from the era such as "Little T&A" by The Rolling Stones, "Sultans of Swing" by Dire Straits, "Dance the Night Away" by Van Halen and "When the Levee Breaks" by Led Zeppelin.[12] For its part, Warner Bros. used its 1972–1984 title featuring the "Big W" logo designed by Saul Bass for Warner Communications to open the film and painted on its studio lot's famed water tower the logo of The Burbank Studios (the facility's name during the 1970s and 1980s when Warner shared it with Columbia Pictures).[13]

Historical accuracy

The Shah and the coup

During the opening prologue, the narrator claims that Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was installed by the 1953 Iranian coup d'état. This is a half-truth; Pahlavi had been shah since 1941, but the coup gave him ultimate authority, whereas, previously, Iran had been a constitutional monarchy wherein Pahlavi followed the advice of Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh.

The narrator says Mossadegh was "overwhelmingly elected as prime minister" by the Iranian people. In truth, he was technically elected prime minister by the Iranian parliament on the base of the elections of 1950, after his predecessor, Haj Ali Razmara, was assassinated. Iranian prime ministers were chosen by parliament members, who were elected by popular vote, as in many parliamentary governments.[14]

Canadian versus CIA roles

After the film was previewed at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 2012,[15] some critics said that it unfairly glorified the role of the CIA and minimized the role of the Canadian government (particularly that of Ambassador Taylor) in the extraction operation. Maclean's asserted that "the movie rewrites history at Canada's expense, making Hollywood and the CIA the saga's heroic saviours while Taylor is demoted to a kindly concierge."[16] The postscript text said that the CIA let Taylor take the credit for political purposes, which some critics thought implied that he did not deserve the accolades he received.[17] In response to this criticism, Affleck changed the postscript text to read: "The involvement of the CIA complemented efforts of the Canadian embassy to free the six held in Tehran. To this day the story stands as an enduring model of international co-operation between governments."[18] The Toronto Star complained, "Even that hardly does Canada justice."[19]

In a CNN interview, President Carter addressed the controversy by stating: "90% of the contributions to the ideas and the consummation of the plan was Canadian. And the movie gives almost full credit to the American CIA. And with that exception, the movie is very good. But Ben Affleck's character in the film was... only in Tehran a day and a half. And the main hero, in my opinion, was Ken Taylor, who was the Canadian ambassador who orchestrated the entire process."[20] Taylor himself noted that, "In reality, Canada was responsible for the six and the CIA was a junior partner. But I realize this is a movie and you have to keep the audience on the edge of their seats."[18] In the film, Taylor is also shown threatening to close the Canadian embassy in the movie; in reality, this did not happen and the Canadians never considered abandoning the six Americans who had taken refuge under Canadian protection.[18]

Affleck asserted: "Because we say it's based on a true story, rather than this is a true story, we're allowed to take some dramatic license. There's a spirit of truth" and that "the kinds of things that are really important to be true are—for example, the relationship between the U.S. and Canada. The U.S. stood up collectively as a nation and said, 'We like you, we appreciate you, we respect you, and we're in your debt.'... There were folks who didn't want to stick their necks out and the Canadians did. They said, 'We'll risk our diplomatic standing, our lives, by harbouring six Americans because it's the right thing to do.' Because of that, their lives were saved."[16]

British and New Zealand roles

Upon its wide release in October 2012, the film was criticized for its claim that the New Zealand and British diplomats had turned away the American refugees in Tehran. Diplomats from New Zealand had proved quite helpful; one drove the Americans to the airport.[21] The British hosted the Americans initially, but the location was not safe and all considered the Canadian ambassador's residence to be the better location. British diplomats also assisted other Americans beyond the six.[22] Bob Anders, the U.S. consular agent played in the film by Tate Donovan, said, "They put their lives on the line for us. We were all at risk. I hope no one in Britain will be offended by what's said in the film. The British were good to us and we're forever grateful."[23]

Sir John Graham, the then-British ambassador to Iran, said, "My immediate reaction on hearing about this was one of outrage. I have since simmered down, but am still very distressed that the film-makers should have got it so wrong. My concern is that the inaccurate account should not enter the mythology of the events in Tehran in November 1979." The then-British chargé d'affaires in Tehran said that, had the Americans been discovered in the British embassy, "I can assure you we'd all have been for the high jump [i.e., in trouble]."[23] Martin Williams, secretary to Sir John Graham in Iran at the time, was the one who found the Americans and sheltered them in his own house at first. The sequence in the film when a housekeeper confronts a truckload of Iranian revolutionary at the Canadian ambassadors home bears a striking resemblance to Mr Williams' own story. He has told how a brave guard, Iskander Khan, confronted heavily-armed revolutionary guards and convinced them that no-one was in when they tried to search Williams' house during a blackout. Mr Williams said "They went away. We and the Americans had a very lucky escape." The fugitives later moved to the home of the Canadian ambassador and his No2.[24]

Affleck is quoted as saying to The Sunday Telegraph: "I struggled with this long and hard, because it casts Britain and New Zealand in a way that is not totally fair. But I was setting up a situation where you needed to get a sense that these six people had nowhere else to go. It does not mean to diminish anyone."[23]

Imminent danger to the group

In the film, the diplomats face suspicious glances from Iranians whenever they go out in public, and appear close to being caught at many steps along the way to their freedom: while pretending to scout for filming locations at a bazaar; while purchasing plane tickets to Zurich; while trying to board the plane; and finally before the plane takes off, when Iranian guards try to stop the plane in a dramatic chase sequence. In reality, the diplomats never appeared to be in imminent danger: the six never went to a bazaar, Taylor's wife bought three sets of plane tickets from three different airlines ahead of time,[16][18] there was no confrontation with security officials at the departure gate,[25][26] and there was no runway chase at the airport.[27]

Other historical inaccuracies

The film contains other historical inaccuracies:

- The climax of film is a chase down an airport runway, as gun-toting members of the Revolutionary Guard try to stop the plane bearing the American refugees from taking off. "Absolutely none of that happened," says Mark Lijek. "Fortunately for us, there were very few Revolutionary Guards about. It's why we turned up for a flight at 5.30 in the morning; even they weren't zealous enough to be there that early. The truth is the immigration officers barely looked at us and we were processed out in the regular way. We got on the flight to Zurich and then we were taken to the US ambassador's residence in Berne. It was that straightforward."[28]

- The part of the plot about the Revolutionary Guards discovering the diplomats' identities is fictional. They had left Iran with their fake identities with no hassle. So the scenes of trouble with the bearded guard at the last check point, the scene of the commander raiding the Canadian ambassador's residence, and the entire chasing scene at the airport and even on the runway are fictional.[29]

- The character of the guards' commander, Ali Khalkhali, is fictional.[29]

- There is a sequence in the film where the six go on a location scout in Tehran to create the impression they are movie people. According to Mark Lijek, the scene is total fiction.[28]

- "It's not true we could never go outside. John Sheardown's house had an interior courtyard with a garden and we could walk there freely," Mark Lijek says.[28]

- The screenplay has the escapees—Mark and Cora Lijek, Bob Anders, Lee Schatz and Joe and Kathy Stafford—settling down to enforced cohabitation at the residence of the Canadian ambassador Ken Taylor. In reality, after several nights—including one spent in the UK residential compound—the group was split between the Taylor house and the home of another Canadian official, John Sheardown.[28][30]

- The major role of producer Lester Siegel, played by Alan Arkin, is fictional.[31]

- The film depicts a dramatic last-minute cancellation of the mission by the Carter administration and a bureaucratic crisis in which Mendez declares he will proceed with the mission. Carter delayed authorization by only 30 minutes, and that was before Mendez had left Europe for Iran.[26]

- In the depiction of a frantic effort at CIA headquarters to get Carter to re-authorize the mission so that previously-purchased airline tickets would still be valid, a CIA officer is portrayed as getting the White House telephone operator to connect him to Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan by impersonating a representative of the school attended by Jordan's children. In reality, Jordan was unmarried and had no children at the time.[32]

- In real life, CIA officer Antonio Mendez has partial Mexican ancestry, leading some critics to argue that Ben Affleck should have cast a Hispanic actor, and not himself, in the role.[33]

- The Hollywood sign is shown dilapidated as it had been in the past, but it had actually been repaired in 1978, prior to the events described in the film.[34]

Release and reception

Critical response

Argo was widely acclaimed by critics. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 96% of critics gave the film positive reviews based on 246 reviews, with an average score of 8.4 out of 10. Its consensus reads: "Tense, exciting and often darkly comic, Argo recreates a historical event with vivid attention to detail and finely wrought characters."[35] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film has received an average score of 86, considered to be "universal acclaim", based on 45 reviews.[36] Naming Argo one of the best 11 films of 2012, critic Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote: "Ben Affleck's seamless direction catapults him to the forefront of Hollywood filmmakers turning out thoughtful entertainment."[37] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 4/4 stars, calling it "spellbinding" and "surprisingly funny". Ebert chose it as his best film of the year.[38]

The Washington Times said it felt "like a movie from an earlier era — less frenetic, less showy, more focused on narrative than sensation" but that the script included "too many characters that he doesn’t quite develop."[39]

The craft in this film is rare. It is so easy to manufacture a thriller from chases and gunfire, and so very hard to fine-tune it out of exquisite timing and a plot that's so clear to us we wonder why it isn't obvious to the Iranians. After all, who in their right mind would believe a space opera was being filmed in Iran during the hostage crisis?

—Roger Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times[38]

Literary critic Stanley Fish says that the film is a standard caper film in which "some improbable task has to be pulled off by a combination of ingenuity, training, deception and luck." He goes on to describe the film's structure: "(1) the presentation of the scheme to reluctant and unimaginative superiors, (2) the transformation of a ragtag bunch of ne'er-do-wells and wackos into a coherent, coordinated unit and (3) the carrying out of the task." Although he thinks the film is good at building and sustaining suspense, he concludes,

This is one of those movies that depend on your not thinking much about it; for as soon as you reflect on what's happening rather than being swept up in the narrative flow, there doesn't seem much to it aside from the skill with which suspense is maintained despite the fact that you know in advance how it's going to turn out. ... Once the deed is successfully done, there's really nothing much to say, and anything that is said seems contrived. That is the virtue of an entertainment like this; it doesn't linger in the memory and provoke afterthoughts.[40]

Jian Ghomeshi, a Canadian writer and radio figure of Iranian descent, thought the film had a "deeply troubling portrayal of the Iranian people". Ghomeshi asserted "among all the rave reviews, virtually no one in the mainstream media has called out [the] unbalanced depiction of an entire ethnic national group, and the broader implications of the portrait." He also suggested that the timing of the film was poor, as American and Iranian political relations were at a low point.[41] A November 3, 2012 article in the Los Angeles Times claimed that the film had received very little attention in Tehran. The article referred to a review by Masoumeh Ebtekar, whose memoirs are the only Iranian narrative of the events.[42]

Despite the Iranian Government's response, sources inside Iran have claimed that the movie has become massively popular, with bootleg copies becoming bestsellers with high prices and copies being sold "by the thousands", making multiple times the sales of Academy Award winner A Separation, which was released almost a year before. Several theaters have been secretly showing the film, including one at Sharif University, with the participants giving a very positive response. Interpretations of the film's popularity in Iran have varied, ranging from the fact that the movie portrays the excesses of the revolution and the hostage crisis, which had been long glorified in Iran to regular Iranians viewing it as a somber reminder of what caused the poor relations with America and the ensuing cost to Iran, decades after the embassy takeover. Other Iranians have claimed that the high DVD sales is a form of silent protest against the government's ongoing hostility to relations with America.[43][44]

The film was nominated for seven Academy Awards except in the Director category and won three for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Achievement in Editing. Following the announcement of the nominations, Bradley Cooper, whose film, Silver Linings Playbook was nominated in several categories, said: "Ben Affleck got robbed."[45] This opinion is shared by the ceremony's host Seth MacFarlane[46] and Quentin Tarantino.[47]

Entertainment Weekly wrote about this controversy:

Standing in the Golden Globe pressroom with his directing trophy, Affleck acknowledged that it was frustrating not to get an Oscar nod when many felt he deserved one. But he's keeping a sense of humor. "I mean, I also didn't get the acting nomination," he pointed out. "And no one's saying I got snubbed there!"[48]

Box office

As of February 24, 2013, the film has earned an estimated $129,653,502 in the United States and Canada, and $77,100,000 in other countries, for a worldwide total of $206,753,502.[2]

Home media

The film was released in North America on February 19, 2013 on DVD, Blu-ray and with an UltraViolet digital copy .[49]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 85th Academy Awards[50] | Best Picture | Grant Heslov, Ben Affleck and George Clooney | Won |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Won | |

| Best Film Editing | William Goldenberg | Won | |

| Best Sound Editing | Erik Aadahl and Ethan Van der Ryn | Nominated | |

| Best Sound Mixing | John Reitz, Gregg Rudloff and Jose Antonio Garcia | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| AFI Awards | Movies of the Year | Ben Affleck, George Clooney, and Grant Heslov | Won |

| 2nd AACTA International Awards[51] | Best Film – International | Grant Heslov, Ben Affleck and George Clooney | Nominated |

| Best Direction – International | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay – International | Chris Terrio | Nominated | |

| British Academy Film Awards[52] | Best Film | Grant Heslov, Ben Affleck, George Clooney | Won |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Leading Role | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Actor in a Supporting Role | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Original Music | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | William Goldenberg | Won | |

| César Award | Best Foreign Film | Ben Affleck | Won |

| Critics Choice Awards | Best Picture | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Acting Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | William Goldenberg | Nominated | |

| Best Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Detroit Film Critics Society | Best Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| 70th Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Best Performance by an Actor in a Supporting Role | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Best Screenplay – Motion Picture | Chris Terrio | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score – Motion Picture | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| International Film Music Critics Association Awards | Film Composer of the Year | Alexandre Desplat, also for Moonrise Kingdom, Rise of the Guardians, Rust and Bone and Zero Dark Thirty | Nominated |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association | Best Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Won |

| National Board of Review Awards 2012 | Top 10 Films | Ben Affleck, George Clooney and Grant Heslov | Won |

| Special Achievement in Filmmaking | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Spotlight Award | John Goodman, also for Flight, ParaNorman and Trouble with the Curve | Won | |

| Nevada Film Critics Society | Best Picture | Won | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck Tied with Kathryn Bigelow for Zero Dark Thirty |

Won | |

| New York Film Critics Online | Best Ensemble Cast | Won | |

| Phoenix Film Critics Society | Top Ten Films | Won | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Ensemble Acting | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay Adaptation | Won | ||

| Best Film Editing | Won | ||

| Roger Ebert | Best Picture of the Year | Won | |

| Directors Guild of America | Best Director | Ben Affleck | Won |

| Producers Guild of America | Best Picture | Ben Affleck, George Clooney and Grant Heslov | Won |

| Screen Actors Guild Awards | Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role | Alan Arkin | Nominated |

| Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture | Cast | Won | |

| San Diego Film Critics Society | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Won | |

| Best Editing | William Goldenberg | Won | |

| Best Production Design | Sharon Seymour | Nominated | |

| Best Score | Alexandre Desplat | Nominated | |

| Best Ensemble Performance | Nominated | ||

| Satellite Awards | Motion Picture | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Alexandre Desplat | Won | |

| St. Louis Film Critics | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| John Goodman | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Nominated | ||

| Washington D. C. Area Film Critics Association | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Ben Affleck | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actor | Alan Arkin | Nominated | |

| Best Acting Ensemble | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Nominated | ||

| Writers Guild of America | Best Adapted Screenplay | Chris Terrio | Won |

References

- ^ "Argo". British Board of Film Classification (BBFC). Retrieved September 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Argo (2012)". Box Office Mojo. January 9, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ a b Bearman, Joshuah (April 24, 2007). "How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran". Wired.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Killoran, Ellen (October 13 2012). "'Argo' Review: Ben Affleck Pinches Himself In Stranger-Than-Fiction CIA Story". International Business Times. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Escape from Iran: The Canadian Caper (TV 1981) - IMDb

- ^ "escape-from-iran-the-canadian-caper-1981-true-story-dvd-94c7%255B2%255D.jpg (image)". Lh4.ggpht.com. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ "Argo Wins the Academy Award For Best Film Editing". Stories99. February 9, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ McNary, Dave (February 3, 2011). "Affleck in talks to direct 'Argo'". Variety.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sneider, Jeff (June 10, 2011). "Alan Arkin first to board 'Argo'". Variety.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Scenes from 'Argo' shot in 'Los Angeles'". filmapia.com. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Staff (September 12, 2011). "Affleck starts shooting 'Argo' film". United Press International.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Text "in LA" ignored (help) - ^ Argo (2012) - Soundtrack.net

- ^ Haithman, Diane (December 31, 2012). "OSCARS: Re-Creating The Look Of The '70s For 'Argo'". Deadline.com.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "The C.I.A. in Iran: Britain Fights Oil Nationalism". The NY Times. Retrieved November 3, 2012.

- ^ Evans, Ian (2012), "Argo TIFF premiere gallery", DigitalHit.com, retrieved January 19, 2013

- ^ a b c Johnson, Brian D. (September 12, 2012). "Ben Affleck rewrites history". Macleans. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Knelman, Martin (September 13, 2012). "TIFF 2012: How Canadian hero Ken Taylor was snubbed by Argo". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Knelman, Martin (September 19, 2012). "Ken Taylor's Hollywood ending: Affleck alters postscript to 'Argo'". Toronto Star. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ Coyle, Jim (October 7, 2012). "'Argo': Former ambassador Ken Taylor sets the record straight". Toronto Star. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ McDevitt, Caitlin (February 22, 2013). "Jimmy Carter: 'Argo' great but inaccurate". Politico. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- ^ "NZ's role in Iran crisis tainted in Affleck's film 'Argo' - Story - Entertainment". 3 News. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ Film. "Ben Affleck's new film 'Argo' upsets British diplomats who helped Americans in Iran". Telegraph. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c Barrett and Jacqui Goddard, David (October 20, 2012). "Ben Affleck's new film 'Argo' upsets British diplomats who helped Americans in Iran". The Telegraph U.K. Retrieved October 21, 2012.

- ^ The Sun 13/02/25 page 7

- ^ Yukon Damov (November 16, 2012). "Diplomats in Iranian hostage crisis discuss Argo: Spoiler alert: Hollywood fudged the facts". The Newspaper. Archived from the original on November 17, 2012.

Wednesday night's conversation between former diplomats Robert Anders and Michael Shenstone, hosted by the U.S. Consulate and the University of Toronto International Relations Society, was an exercise in displaying Hollywood's manipulation of historical reality.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead=ignored (help) - ^ a b Mendez, Antonio J. (Winter 1999–2000). "CIA Goes Hollywood: A Classic Case of Deception". Studies in Intelligence. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ 19 Photos (October 10, 2012). "Tony Mendez, clandestine CIA hero of Ben Affleck's 'Argo,' reveals the real story behind film smash". Washington Times. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Dowd, Vincent (January 14, 2013). "BBC News - Argo: The true story behind Ben Affleck's Globe-winning film". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ a b By Joshuah BearmanEmail Author. "How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans From Tehran | Wired Magazine". Wired.com. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Martin, Douglas (January 4, 2013). "John Sheardown, Canadian Who Sheltered Americans in Tehran, Dies at 88". New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ "How accurate is Argo". www.slate.com. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (February 16, 2013). "The Oscar for Best Fabrication". New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Navarrette, Ruben (January 10, 2013). "Latino should have played lead in 'Argo'". CNN. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "The History of the Sign: 1978: A Sign is Reborn". Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ "Argo". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved November 17, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Argo Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Holden, Stephen (December 14, 2012). "The Year of the Body Vulnerable". The New York Times. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (10 October 2012). Argo. Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- ^ Peter Suderman, Movie Review: 'Argo', The Washington Times, October 11, 2012

- ^ Fish, Stanley (October 29, 2012). "The 'Argo' Caper". The New York Times. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

- ^ Ghomeshi, Jian (November 2, 2012). "Argo is crowd-pleasing, entertaining – and unfair to Iranians". Globe and Mail. Retrieved November 5, 2012.

- ^ Mostaghim, Ramin (November 3, 2012). "U.S. film 'Argo' not getting any buzz in Iran". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles: Tribune Company. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Outlawed 'Argo' DVDs are selling by the thousands in Iran". GlobalPost. February 1, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Kamali, Saeed (November 13, 2012). "Why Argo is hard for Iranians to watch | World news | guardian.co.uk". Guardian. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Carneiro, Bianca (January 10, 2013). "'Ben Affleck was robbed': Best actor nominee Bradley Cooper on Argo star's Oscars snub". Daily Mail. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ Macatee, Rebecca (January 10, 2013). "Ben Affleck's Oscars Snub: Bradley Cooper, Seth MacFarlane Think Argo Director Was Robbed". E! Online. NBCUniversal. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino thinks Ben Affleck's Oscar snub was worse than his | NDTV Movies.com". Movies.ndtv.com. February 18, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ "The Oscars / 2013: Eyes on the Prize". Entertainment Weekly. New York: Time Inc.: 22 January 25/February 1, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Argo Blu-Ray". Blu-Ray.com. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ^ "The Nominees". OSCAR. January 10, 2013. Retrieved January 10, 2013.

- ^ Garry, Maddox (January 9, 2013). "Jackman, Kidman up for AACTA awards". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ "EE British Academy Film Awards Nominations in 2013". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. January 9, 2013. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- Further reading

- "Why Argo is hard for Iranians to watch." The Guardian. November 13, 2012.

External links

- Official website

- Argo at IMDb

- Argo at AllMovie

- Argo at Rotten Tomatoes

- Argo at Metacritic

- Argo at Box Office Mojo

- 2012 films

- American political drama films

- American political thriller films

- Anti-Iranian sentiments

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Canada–United States relations in popular culture

- Central Intelligence Agency in fiction

- English-language films

- Films about filmmaking

- Films based on actual events

- Films directed by Ben Affleck

- Films set in 1979

- Films set in 1980

- Films set in Iran

- Films set in Istanbul

- Films set in Tehran

- Films set in Los Angeles, California

- Films set in Virginia

- Films set in Washington, D.C.

- Films shot in Los Angeles, California

- Films shot in Turkey

- Films shot in Virginia

- Films whose director won the Best Director Golden Globe

- Iranian Revolution films

- Persian-language films

- Warner Bros. films

- Best Foreign Language Film César Award winners

- Films whose editor won the Best Film Editing Academy Award

- Films whose writer won the Best Adapted Screenplay Academy Award

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- Journalism adapted into films