Bob Hope

Bob Hope | |

|---|---|

Hope in 1978 | |

| Born | Leslie Townes Hope May 29, 1903 Eltham, London, England, UK |

| Died | July 27, 2003 (aged 100) Toluca Lake, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Pneumonia |

| Resting place | San Fernando Mission Cemetery |

| Nationality | British American |

| Other names | Les Hope, Packy East |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, comedian, singer, author, athlete |

| Years active | 1919–98 |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Louise Troxell (1933–34) Dolores Hope (1934–2003; his death) |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Jack Hope (brother) |

| Boxing career | |

| Awards | List of awards and nominations received by Bob Hope |

| Statistics | |

| Weight(s) | Super Featherweight (128 lb) |

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (178 cm) |

| Reach | 72 in (183 cm) |

| Website | bobhope |

| Signature | |

Bob Hope, KBE, KC*SG, KSS (born Leslie Townes Hope, May 29, 1903 – July 27, 2003) was an English-American comedian, vaudevillian, actor, singer, dancer, athlete, and author. With a career spanning nearly 80 years, Hope appeared in over 70 films and shorts, including a series of "Road" movies also starring Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. In addition to hosting the Academy Awards 19 times (more than any other host), he appeared in many stage productions and television roles and was the author of fourteen books. The song "Thanks for the Memory" is widely regarded as Hope's signature tune.

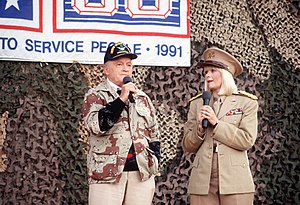

Born in London, England, Hope arrived in America with his family at the age of four and grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. He began his career in show business in the early 1920s, initially on stage, and began appearing on the radio and in films in 1934. He was praised for his comedy timing, specializing in one-liners and rapid-fire delivery of jokes—which were often self-deprecating, with Hope building himself up and then tearing himself down. Celebrated for his long career performing United Service Organizations (USO) shows to entertain active service American military personnel—he made 57 tours for the USO between 1941 and 1991—Hope was declared an honorary veteran of the United States Armed Forces in 1997 by act of the U.S. Congress.[1] He also appeared in numerous specials for NBC television, starting in 1950, and was one of the first users of cue cards.

Hope participated in the sports of golf and boxing, and owned a small stake in his hometown baseball team, the Cleveland Indians. He was married to performer Dolores Hope (née DeFina) for 69 years. Hope died at the age of 100 at his home in Toluca Lake, California.

Early years

Hope was born in Eltham, London (now part of the London Borough of Greenwich), the fifth of seven sons. His English father, William Henry Hope, was a stonemason from Weston-super-Mare, Somerset, and his Welsh mother, Avis (Townes), was a light opera singer from Barry[2] who later worked as a cleaner. They married in April 1891 and lived at 12 Greenwood Street, Barry, before moving to Whitehall and then St George, both in Bristol. In 1908, the family emigrated to the United States aboard the SS Philadelphia and passed through Ellis Island on March 30, 1908, before moving to Cleveland, Ohio.[3]

From age 12, Hope earned pocket money by busking (frequently on the streetcar to Luna Park), singing, dancing, and performing comedy.[4] He entered many dancing and amateur talent contests (as Lester Hope) and won a prize in 1915 for his impersonation of Charlie Chaplin.[5] For a time, he attended the Boys' Industrial School in Lancaster, Ohio. As an adult, he donated sizable sums of money to the institution.[6]

Hope had a brief career as a boxer in 1919 fighting under the name Packy East. He had three wins and one loss, and participated in a few staged charity bouts later in life.[7]

Hope worked as a butcher's assistant and a lineman in his teens and early twenties. Hope also had a brief stint at Chandler Motor Car Company. Deciding on a show business career, he and his girlfriend signed up for dancing lessons. Encouraged after they performed in a three-day engagement at a club, Hope formed a partnership with Lloyd Durbin, a friend from the dancing school.[8] Silent film comedian Fatty Arbuckle saw them perform in 1925 and found them work with a touring troupe called Hurley's Jolly Follies. Within a year, Hope had formed an act called the Dancemedians with George Byrne and the Hilton Sisters, conjoined twins who performed a tap dancing routine in the vaudeville circuit. Hope and Byrne had an act as a pair of Siamese twins as well, and danced and sang while wearing blackface, before friends advised Hope that he was funnier as himself.[9]

In 1929, Hope informally changed his first name to "Bob". In one version of the story, he named himself after racecar driver Bob Burman.[10] In another, he said he chose the name because he wanted a name with a "friendly 'Hiya, fellas!' sound" to it.[11] In a 1942 legal document, Hope's legal name is given as Lester Townes Hope; it is unknown if this reflects a legal name change from Leslie.[12] After five years on the vaudeville circuit, Hope was "surprised and humbled" when he failed a 1930 screen test for the French film production company Pathé at Culver City, California.[13]

Career

In the early days, Hope's career included appearances on stage in Vaudeville shows and Broadway productions. He began performing on the radio in 1934 and switched to television when that medium became popular in the 1950s. He began doing regular TV specials in 1954,[14] and hosted the Academy Awards fourteen times in the period from 1941 to 1978.[15] Overlapping with this was his movie career, spanning the years 1934 to 1972, and his USO tours, which he did from 1941 to 1991.[16][17]

Film

Hope signed a contract for six short films with Educational Pictures of New York. The first was a comedy, Going Spanish (1934). He was not happy with the film, and told Walter Winchell, "When they catch John Dillinger, they're going to make him sit through it twice."[18] Educational dropped his contract, but he soon signed with Warner Brothers. He made movies during the day and performed Broadway shows in the evenings.[19]

Hope moved to Hollywood when Paramount Pictures signed him for the 1938 film The Big Broadcast of 1938, also starring W. C. Fields. The song "Thanks for the Memory", which later became his trademark, was introduced in this film as a duet with Shirley Ross as accompanied by Shep Fields and his orchestra.[20] The sentimental, fluid nature of the music allowed Hope's writers (he depended heavily upon joke writers throughout his career[21]) to later create variations of the song to fit specific circumstances, such as bidding farewell to troops while on tour.[22]

As a movie star, he was best known for comedies like My Favorite Brunette and the highly successful "Road" movies in which he starred with Bing Crosby and Dorothy Lamour. The series consists of seven films made between 1940 and 1962, Road to Singapore (1940), Road to Zanzibar (1941), Road to Morocco (1942), Road to Utopia (1946), Road to Rio (1947), Road to Bali (1952), and The Road to Hong Kong (1962). Hope had seen Lamour as a nightclub singer in New York,[23] and invited her to work on his United Service Organizations (USO) tours. Lamour sometimes arrived for filming prepared with her lines, only to be baffled by completely re-written scripts or ad-lib dialogue between Hope and Crosby.[24] Hope and Lamour were lifelong friends, and she remains the actress most associated with his film career. Hope made movies with dozens of other leading ladies, including Katharine Hepburn, Paulette Goddard, Hedy Lamarr, Lucille Ball, Rosemary Clooney, Jane Russell and Elke Sommer.[25]

Hope teamed with Crosby for the "Road" pictures and countless stage, radio, and television appearances over the decades, from their first meeting in 1932[26] until Crosby's death in 1977. The two invested together in oil leases and other business ventures, but did not see each other socially.[27]

After the release of Road to Singapore (1940), Hope's screen career took off, and he had a long and successful career in the movies. After an 11-year hiatus, Hope and Crosby teamed up for the last Road movie, The Road to Hong Kong (1962), starring 28-year-old Joan Collins in place of Lamour, who Hope and Crosby thought was too old for the part.[28] They had planned one more movie together in 1977, The Road to the Fountain of Youth. Filming was postponed when Crosby was injured in a fall, and the production was cancelled when he suddenly died of heart failure that October.[29]

Hope starred in 54 theatrical features between 1938 and 1972,[30] as well as cameos and short films. Most of Hope's later movies failed to match the success of his 1940s efforts. He was disappointed with his appearance in Cancel My Reservation (1972), his last starring film, and the movie was poorly received by critics and filmgoers.[31] Though his career as a film star effectively ended in 1972, Hope made a few cameo appearances in films into the 1980s.

Hope was host of the Academy Awards ceremony fourteen times between 1939 and 1977. His feigned desire for an Academy Award became part of his act.[15] Although he was never nominated for an Oscar, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honored him with four honorary awards, and in 1960, the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. While introducing the 1968 telecast, he quipped, "Welcome to the Academy Awards, or, as it's known at my house, Passover."[32]

Broadcasting

Hope's career in broadcasting began on radio in 1934. His first regular series for NBC Radio was the Woodbury Soap Hour in 1937, a 26-week contract. A year later, The Pepsodent Show Starring Bob Hope began, and Hope signed a ten-year contract with the show's sponsor, Lever Brothers. Hope hired eight writers and paid them out of his salary of $2,500 a week. The original staff included Mel Shavelson, Norman Panama, Jack Rose, Sherwood Schwartz, and Schwartz's brother Al. The writing staff eventually grew to fifteen.[33] The show became the top radio program in the country. Regulars on the series included Jerry Colonna and Barbara Jo Allen as spinster Vera Vague. Hope continued his lucrative career in radio through to the 1950s, when radio's popularity was overshadowed by television.[34][35]

NBC comedy specials

Hope did many specials for the NBC television network in the following decades, beginning in April 1950. He was one of the first people to use cue cards. The shows were often sponsored by General Motors (1955–61), Chrysler (1963–73), and Texaco (1975–85).[36] Hope's Christmas specials were popular favorites and often featured a performance of "Silver Bells" (from his 1951 film The Lemon Drop Kid) done as a duet with an often much younger female guest star (such as Olivia Newton-John, Barbara Eden, and Brooke Shields[37]), or with his wife Dolores, with whom he dueted on two specials. Hope's 1970 and 1971 Christmas specials for NBC—filmed in Vietnam in front of military audiences at the height of the war—are on the list of the Top 46 U.S. network prime-time telecasts. Both were seen by more than 60 per cent of the U.S. households watching television.[38]

In 1992, Hope made a guest appearance as himself on The Simpsons, in the episode "Lisa the Beauty Queen" (season 4, episode 4).[39] His 90th birthday television celebration in May 1993, Bob Hope: The First 90 Years, won an Emmy Award for Outstanding Variety, Music Or Comedy Special.[40] Towards the end of his career, eye problems left him unable to read his cue cards.[41] In October 1996 Hope announced that he was ending his 60-year contract with NBC, joking that he "decided to become a free agent".[42] His final television special, Laughing with the Presidents, was broadcast in November 1996, with host Tony Danza helping him present a personal retrospective of presidents of the United States known to the comedian. The special received poor reviews.[43] Following a brief appearance at the 50th Primetime Emmy Awards in 1997, Hope's last TV appearance was in a 1997 commercial with the introduction of Big Kmart directed by Penny Marshall.[44]

USO

While aboard the RMS Queen Mary when World War II began in September 1939, Hope volunteered to perform a special show for the passengers, during which he sang "Thanks for the Memory" with rewritten lyrics.[45] He performed his first USO show on May 6, 1941, at March Field, California,[46] and continued to travel and entertain troops for the rest of World War II, later during the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the third phase of the Lebanon Civil War, the latter years of the Iran–Iraq War, and the 1990–91 Persian Gulf War.[17] His USO career lasted half a century, during which he headlined 57 tours.[17] He had a deep respect for the men and women who served in the military, and this was reflected in his willingness to go anywhere in order to entertain them.[47] During the Vietnam War, Hope had trouble convincing some performers to join him on tour. Anti-war sentiment was high, and Hope's pro-troop stance made him a target of criticism. Some shows were drowned out by boos and others were listened to in silence.[48] The tours were funded by the United States Department of Defense, his television sponsors, and by NBC, the network which broadcast the television specials that were created after each tour.

Hope recruited his own family members for USO travel. His wife, Dolores, sang from atop an armored vehicle during the Desert Storm tour, and his granddaughter, Miranda, appeared alongside Hope on an aircraft carrier in the Indian Ocean.[47] Of Hope's USO shows in World War II, writer John Steinbeck, who was then working as a war correspondent, wrote in 1943:

When the time for recognition of service to the nation in wartime comes to be considered, Bob Hope should be high on the list. This man drives himself and is driven. It is impossible to see how he can do so much, can cover so much ground, can work so hard, and can be so effective. He works month after month at a pace that would kill most people.[49]

For his service to his country through the USO, he was awarded the Sylvanus Thayer Award by the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1968.[50] A 1997 act of Congress signed by President Bill Clinton named Hope an "Honorary Veteran." He remarked, "I've been given many awards in my lifetime — but to be numbered among the men and women I admire most — is the greatest honor I have ever received."[51] In homage to Hope, Stephen Colbert carried a golf club on stage each night during his own week of USO performances, which were taped for his TV show, The Colbert Report, during the 2009 season.[52]

Theater

Hope's first Broadway appearances, in 1927's The Sidewalks of New York and 1928's Ups-a-Daisy, were minor walk-on parts.[53] He returned to Broadway in 1933 to star as Huckleberry Haines in the Jerome Kern / Dorothy Fields musical Roberta.[54] Stints in the musicals Say When, the 1936 Ziegfeld Follies (with Fanny Brice), and Red, Hot and Blue with Ethel Merman and Jimmy Durante followed.[55] Hope reprised his role as Huck Haines in a 1958 production of Roberta at The Muny Theater in Forest Park, St. Louis, Missouri.[56]

Hope rescued Eltham Little Theatre from closure by providing funds to buy the property. He continued his interest and support and regularly visited when in London. The theatre was renamed in his honor in 1982.[57]

Critical reception

Hope was praised for his comedy timing, specializing in one-liners and rapid-fire delivery of jokes. His style of delivery of self-deprecating jokes, first building himself up and then tearing himself down, was unique. Working tirelessly, he performed hundreds of times per year.[58] Early films such as The Cat and the Canary (1939) and The Paleface (1948) were financially successful and were praised by critics,[59] and by the mid-1940s, with his radio program getting good ratings as well, he became one of the most popular entertainers in the United States.[60] When Paramount threatened to stop production of the Road pictures in 1945, they received 75,000 letters in protest.[61] He had no faith in his skills as a dramatic actor, and his performances of that type were not as well received.[62] Hope had been a leader in the radio medium until the late 1940s, but as his ratings began to slip, he switched to television in the 1950s, an early pioneer of that medium.[37][63] He published several books—written with ghostwriters—about his wartime experiences.[60]

Although he made an effort to keep his material up-to-date, he never adapted his comic persona or his routines to any great degree. As Hollywood began to transition to the New Hollywood era in the 1960s, Hope reacted negatively such as when he hosted the 40th Academy Awards in 1968, and voiced his contempt such as mocking at its delay due to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and greeting attending younger actors on stage like Dustin Hoffman (who was 30 at the time) as children.[64] By the 1970s his popularity was beginning to wane with soldiers and with the movie-going public.[65] However, he continued doing USO tours into the 1980s,[66] and he continued to appear on television into the 1990s. Nancy Reagan called him "America's most honored citizen and our favorite clown."[67]

Hope was an avid golfer, playing in as many as 150 charity tournaments a year.[68] Introduced to the game in the 1930s while performing in Winnipeg,[69] he eventually played to a four handicap. His love for the game—and the humor he could find in it—made him a sought-after foursome member. He once remarked that President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave up golf for painting – "fewer strokes, you know."[70] "It's wonderful how you can start out with three strangers in the morning, play 18 holes, and by the time the day is over you have three solid enemies," he once said.[71]

A golf club became an integral prop for Hope during the standup segments of his television specials and USO shows. In 1978, he putted against a then two-year-old Tiger Woods in a television appearance with James Stewart on The Mike Douglas Show.[72]

The Bob Hope Classic, founded in 1960, made history in 1995 when Hope teed up for the opening round in a foursome which included Presidents Gerald Ford, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton – the only time when three presidents played in the same golf foursome.[73] Now known as the Humana Challenge, it was one of the few PGA Tour tournament that took place over five rounds, until the 2012 tournament, when it was cut back to the conventional four rounds.[74]

Hope bought a small stake in the Cleveland Indians baseball team in 1946[75] and owned it for most of the rest of his life.[76] He appeared on the June 3, 1963, cover of Sports Illustrated magazine wearing an Indians uniform,[77] and sang a special version of "Thanks for the Memory" after the Indians' last game at Cleveland Stadium on October 3, 1993.[78] Hope bought a share of the Los Angeles Rams football team in 1947 with Bing Crosby[79] and sold it in 1962.[80] He would frequently use his television specials to promote the annual AP College Football All-America Team. The players would enter the stage one-by-one and introduce themselves, and Hope, often dressed in a football uniform, would give a one-liner about the player or his school.[81]

Personal life

Marriages

Hope's first, short-lived marriage was to vaudeville partner Grace Louise Troxell, a secretary from Chicago, Illinois, and daughter of Edward and Mary (McGinnes) Troxell, whom he married in January 25, 1933 in Erie, Pennsylvania with Alderman Eugene Alberstadt officiating [82][83] and divorced in November 1934.[84]

They shared headlines with Joe Howard at the Palace Theatre in April 1931, performing "Keep Smiling" and the "Antics of 1931.[85]"The couple was working together at the RKO Albee, performing the "The Antics of 1933" along with Ann Gillens and Johnny Peters in June 1933.[86]

In July 1933, Dolores Reade joined Bob's vaudeville troop and was performing with him at Loew's Metropolitan Theater. She was described as a "former Zeigfield beauty and one of society's favorite nightclub entertainers, having appeared at many private social functions at New York, Palm Beach, and Southampton."[87]

In February 1934,[88] Hope married Dolores (DeFina) Reade, who had been one of his co-stars on Broadway in Roberta. In his 2014 biography Richard Zoglin states that he could find no evidence of the marriage having taken place, and notes that Hope was still married to Troxell at the time.[84] The couple adopted four children at an adoption agency called The Cradle, in Evanston, Illinois: Linda (1939), Tony (1940), Kelly (1946), and Eleanora (known as Nora)(1946).[89] From them he had several grandchildren, including Andrew, Miranda, and Zachary Hope. Tony (as Anthony J. Hope) served as a presidential appointee in the George H. W. Bush and Clinton administrations and in a variety of posts under Presidents Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan.[90]

The couple lived at 10342 Moorpark Street in Toluca Lake, California from 1937 until his death. In 1935, they lived in Manhattan.[91]

Extramarital affairs

Hope had a reputation as a womanizer and continued to see other women in spite of his marriage.[92] In 1949, while Hope was in Dallas on a publicity tour for his radio show, he met starlet Barbara Payton, a contract player at Universal Studios, who at the time was on her own public relations jaunt. Shortly thereafter, Hope set Payton up in an apartment in Hollywood.[93] The arrangement soured as Hope was not able to satisfy Payton's definition of generosity and her need for attention.[94] Hope paid her off to end the affair quietly. Payton later revealed the affair in an article printed in July 1956 in Confidential.[95] "Hope was ... at times a mean-spirited individual with the ability to respond with a ruthless vengeance when sufficiently provoked."[96] His advisors counseled him to avoid further publicity by ignoring the Confidential exposé.[96] "Barbara's ... revelations caused a minor ripple ... and then quickly sank without causing any appreciable damage to Bob Hope's legendary career."[96] According to Arthur Marx's Hope biography, The Secret Life of Bob Hope, Hope's subsequent long-term affair with actress Marilyn Maxwell was so open that the Hollywood community routinely referred to her as "Mrs. Bob Hope".[97]

Activism

Hope served as an active honorary chairman on the board of Fight for Sight. He hosted their Lights On telecast in 1960 and donated $100,000 to establish the Bob Hope Fight for Sight Fund.[98] He recruited numerous top celebrities for the annual "Lights On" fundraiser; as an example, he hosted Joe Frazier, Yvonne De Carlo, and Sergio Franchi as headliners for the show at Philharmonic Hall in Milwaukee on April 25, 1971.[99]

Later years

Hope continued an active career past his 75th birthday, concentrating on his television specials and USO tours. Although he had given up starring in movies after Cancel My Reservation, he made several cameos in various films and co-starred with Don Ameche in the 1986 TV movie A Masterpiece of Murder.[100] A television special created for his 80th birthday in 1983 at the Kennedy Center in Washington featured President Ronald Reagan, Lucille Ball, George Burns, and many others.[101] In 1985, he was presented with the Life Achievement Award at the Kennedy Center Honors,[102] and in 1998 he was appointed an honorary Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II. Upon accepting the appointment, Hope quipped, "I'm speechless. 70 years of ad lib material and I'm speechless."[103]

At the age of 95, Hope made an appearance at the 50th anniversary of the Primetime Emmy Awards with Milton Berle and Sid Caesar.[104] Two years later, he was present at the opening of the Bob Hope Gallery of American Entertainment at the Library of Congress. The Library of Congress has presented two major exhibitions about Hope's life – "Hope for America: Performers, Politics and Pop Culture" and "Bob Hope and American Variety."[105][106]

Hope celebrated his 100th birthday on May 29, 2003.[107] He is among a small group of notable centenarians in the field of entertainment. To mark this event, the intersection of Hollywood and Vine in Los Angeles was named "Bob Hope Square" and his centennial was declared "Bob Hope Day" in 35 states. Even at 100, Hope maintained his self-deprecating sense of humor, quipping, "I'm so old, they've canceled my blood type."[108] He converted to Roman Catholicism late in life.[109]

Illness and death

In 1998, a prepared obituary by the Associated Press was inadvertently released, prompting Hope's death to be announced in the U.S. House of Representatives.[110][111] Hope remained in good health until old age, though he became slightly frail.[112] In June 2000, he spent nearly a week in a California hospital after being hospitalized for gastrointestinal bleeding.[113] In August 2001, he spent close to two weeks in the hospital recovering from pneumonia.[114]

On the morning of July 27, 2003, two months after his 100th birthday, Hope died of pneumonia at his home in Toluca Lake, California.[108] His grandson, Zach Hope, told Soledad O'Brien that when asked on his deathbed where he wanted to be buried, Hope had told his wife, "Surprise me."[115] He was interred in the Bob Hope Memorial Garden at San Fernando Mission Cemetery in Los Angeles, joined in 2011 by wife Dolores, when she died four months after her 102nd birthday.[116] After his death, newspaper cartoonists worldwide paid tribute to his work for the USO or featured Bing Crosby (who died in 1977) welcoming Hope into heaven.[117]

Estate

Hope's Modernist 23,366-square-foot (2,171 m2) home, built to resemble a volcano, was designed in 1973 by John Lautner. Located above Palm Springs, it has panoramic views of the Coachella Valley and the San Jacinto Mountains. The house was placed on the market for the first time in February 2013 with an asking price of $50 million.[118] Hope also owned a home which had been custom built for him in 1939 on an 87,000-square-foot (8,083 m2) lot in Toluca Lake. The house was placed on the market in late 2012.[119]

Awards and honors

Hope was awarded over two thousand honors and awards, including 54 honorary doctorates. In 1963 President John F. Kennedy awarded him the Congressional Gold Medal for service to his country.[120] President Lyndon Johnson bestowed the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Hope in 1969 for his service to the men and women of the armed forces through the USO.[121] In 1982, he received the S. Roger Horchow Award for Greatest Public Service by a Private Citizen, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[122] He was presented with the National Medal of Arts in 1995[123] and received the Ronald Reagan Freedom Award in 1997.[124] Hope became the 64th and only civilian recipient of the United States Air Force Order of the Sword on June 10, 1980. The Order of the Sword recognizes individuals who have made significant contributions to the enlisted corps.[125]

Several buildings and facilities were renamed after Hope, including the historic Fox Theater in downtown Stockton, California,[126] and the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank.[127] There is a Bob Hope Gallery at the Library of Congress.[128] In memory of his mother, Avis Townes Hope, Bob and Dolores Hope gave the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, DC a chapel, the Chapel of Our Lady of Hope.[129] USNS Bob Hope (T-AKR-300) of the U.S. Military Sealift Command was named after the performer in 1997. It is one of very few U.S. naval ships that were named after living people.[130] The United States Air Force named a C-17 Globemaster III transport aircraft the Spirit of Bob Hope.[131]

In Hope's hometown of Cleveland, the refurbished Lorain-Carnegie Bridge was renamed the Hope Memorial Bridge in 1983 (though differing claims have been made as to whether the bridge honors Hope himself, his entire family, or his stonemason father Harry - who helped in the bridge's construction). Also, East 14th Street near Playhouse Square (Cleveland's theater district) was renamed Memory Lane-Bob Hope Way in 2003 in honor of the entertainer's 100th birthday.[132]

Academy Awards

Although he was never nominated for a competitive Oscar, Hope was awarded five honorary awards by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences:[133]

- 13th Academy Awards (1940): Special Award – in recognition of his unselfish services to the motion picture industry

- 17th Academy Awards (1944): Special Award – for his many services to the Academy

- 25th Academy Awards (1952): Honorary Award – for his contribution to the laughter of the world, his service to the motion picture industry, and his devotion to the American premise

- 32nd Academy Awards (1959): Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award

- 38th Academy Awards (1965): Honorary Award – for unique and distinguished service to the industry and the Academy

Discography

Singles

| Year | Single | US Pop Chart[134] |

|---|---|---|

| 1938 | "Thanks for the Memory" (A-side) (Bob Hope and Shirley Ross) | — |

| 1939 | "Two Sleepy People" (B-side) (Bob Hope and Shirley Ross) | 15 |

| 1945 | "The Road to Morocco" (Bing Crosby and Bob Hope) | 21 |

| 1950 | "Blind Date" (Margaret Whiting and Bob Hope) | 16 |

Bibliography

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "Committee Reports: 105th Congress (1997–1998): House Report 105-109". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Barry Ideas Bank". Crowdicity. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- ^ Moreno 2008, p. 88.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 4.

- ^ "Bob Hope and the American Variety: Early Life". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ^ "Boys' Industrial School". Ohio Historical Society. July 1, 2005. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ "Bob Hope". Boxing-scoop.com. Retrieved April 11, 2012.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 19–23.

- ^ Faith 2003, pp. 402–403.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "Bob Hope and American Variety: On the Road: USO Shows". Library of Congress. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 229.

- ^ a b Grudens 2002, p. 154.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 318–320.

- ^ a b c Grudens 2002, pp. 181–182.

- ^ Maltin 1972, p. 25.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 105, 107.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 110, 113.

- ^ Lahr 1998.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 133.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 174–180.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 127.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 127, 137.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 265.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 287.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 41.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 285–286.

- ^ McCaffrey 2005, p. 56.

- ^ Nachman 1998, p. 144.

- ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 92–103.

- ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Grudens 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 48.

- ^ "The Simpsons: Lisa and the Beauty Queen". Fox Broadcasting Company. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Hope: The First 90 Years: NBC". Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 291.

- ^ Errico, Marcus (October 23, 1996). "Bob Hope Liberated from NBC After 60 Years". E! Entertainment Television. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ Seely, Mike (November 30, 2005). "Bob Hope's Laughing with the Presidents (1997)". The Riverfront Times. Village Voice Media Holdings. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Lorencz, Mary; Baldwin, Paula (October 23, 1997). "Kmart Launches Celebrity-Studded TV Ad Campaign for New Big Kmart". Press release. Sears Holdings Corporation. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Friedrich 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 113.

- ^ a b

King, Larry (August 27, 2003). "Interview Q&A between Hope-Smith and Z. Hope: Tribute to Bob Hope". Larry King Live. CNN Transcripts.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 251, 254, 258.

- ^ Steinbeck 1958, p. 65.

- ^ "1968 Sylvanus Thayer Award: Bob Hope". West Point Association of Graduates. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ Faith 2003, p. 429.

- ^ "A salute for Stephen Colbert". Los Angeles Times. Eddy Hartenstein. June 13, 2009. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Faith 2003, p. 403.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 73–75.

- ^ "Comedian Bob Hope opened in The Muny's production of Roberta". The Muny. June 16, 1958. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Hope's 100th Birthday". The Bob Hope Theatre. May 29, 2003. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 158.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 123, 183.

- ^ a b Quirk 1998, p. 153.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 172.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 184, 187.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Harris, Mark (2008). Pictures at a Revolution. Penguin Press. p. 409.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 255, 276, 314.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 161.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 312.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 57.

- ^ McCarten, Barry (August 12, 2012). "History and Live Theatre in Winnipeg". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved August 31, 2012.

- ^ West, Bob (May 31, 1980). "Bob Hope hooked for life by golf, Hughen students". The Port Arthur News. Roger Underwood. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ "Profile: Bob Hope". World Golf Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ^ "New era dawns in California desert". Fox Broadcasting Company. January 18, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Tournament History". Bob Hope Chrysler Classic. Archived from the original on March 1, 2000. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ "Humana Challenge Unveils Tournament Details and Structure at Media Day". Business Wire. December 6, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Bing Crosby Buys Chunk of Pirates As Club Sold to New Owners' Group". Windsor Daily Star. August 9, 1946. p. Second section, p. 3.

- ^ Rea, Steven X (August 21, 1982). "Why Bob Hope's Still on the Road". Montreal Gazette. Alan Allnutt. p. E–1. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "SI Vault: Bob Hope". Sports Illustrated. Turner Sports & Entertainment Digital Network. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ Dawidziak, Mark (May 29, 2003). "For our favorite son Bob Hope, all roads lead back home to Ohio". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Advance Publications. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Reeves Gives Up Active Interest in L-A Rams". Lewiston Daily Sun. December 28, 1949. p. 8. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ "Reeves Buys Rams For $4.8 Million". Lodi News-Sentinel. Marty Weybret. December 28, 1962. p. 9.

- ^ "FWAA Names 2009 All-American Team". Football Writers Association of America. December 12, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ^ "Pennsylvania, County Marriages, 1885-1950," database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:VFQR-NPT), William H Hope in entry for Leslie T Hope and Grace L Troxell, January 25, 1933; citing Marriage, Pennsylvania, county courthouses, Pennsylvania; FHL microfilm 2,259,873.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 66.

- ^ a b Sheridan, Peter (August 16, 2014). "Bob Hope the Bigamist". Daily Express. Retrieved August 16, 2014.

- ^ The Scranton Republican, Scranton, Pennsylvania, Monday, April 27, 1931, p. 4

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn, New York, Wednesday, June 28, 1933, p. 35

- ^ Eagle Brooklyn, New York, Saturday, July 14, 1933, p. 5

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 81.

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ^ "Anthony J. Hope, 63, Head Of Panel and Bob Hope's Son". The New York Times. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, Jr. July 2, 2004. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ 1940 US Census via Ancestry.com

- ^ Quirk 1998, pp. 82, 90.

- ^ O'Dowd 2006, p. 65.

- ^ O'Dowd 2006, pp. 66, 67.

- ^ O'Dowd 2006, p. 311.

- ^ a b c O'Dowd 2006, p. 313.

- ^ Marx, Arthur (1993). The Secret Life of Bob Hope: An Unauthorized Biography. Fort Lee, New Jersey: Barricade Books. ISBN 978-0-942637-74-8.

- ^ "History: Fight for Sight Leaders: Lights On Fundraiser, Celebrity Supporters". Fight for Sight. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ Wilson, Earl (April 14, 1971). "Sergio Franchi & Yvonne de Carlo featured at "Fight for Sight" Benefit". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Milwaukee, WI: Elizabeth Brenner.

- ^ "A Masterpiece of Murder (1896)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "The Bob Hope Show: Happy Birthday, Bob!". CBS Corporation. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "History of Past Honorees". Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Ward, Linda. "Bob Hope: Thanks for the memory". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ Gallo, Phil (September 12, 1998). "The 50th Annual Primetime Emmy Awards". Variety. Reed Business Information. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Hope for America: Performers, Politics and Pop Culture". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Hope and American Variety". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Hope's 100th birthday greeted with good wishes". USA Today. Gannett Company. Associated Press. May 30, 2003. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ a b "Comedian Bob Hope dies". BBC News. July 28, 2003. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ "St. Charles Catholic Church". Gary Wayne. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ House Session. C-SPAN. June 5, 1998. Event occurs at 6:01:45. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Quirk 1998, p. 313.

- ^ Grudens 2002, p. 148.

- ^ "Bob Hope released from hospital". CNN. June 7, 2000. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "Bob Hope stays in hospital". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. September 4, 2001. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ O'Brien, Soledad (July 29, 2003). "Hope grandson: Laughter until the end". CNN. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Doyle, Paula (August 23, 2005). "Bob Hope Memorial Garden opens at San Fernando Mission". Catholic News Service. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "In Memory of Bob Hope". Forward Air Controllers Association. Retrieved June 10, 2012.

- ^ Higgins, Michelle (February 25, 2013). "Bob Hope Estate in Palm Springs Is Up for Sale". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2013.

- ^ Mikailian 2012.

- ^ Grudens 2002, pp. 152–153.

- ^ "Great American Patriot Bob Hope". USA Patriotism. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ "National Winners: Public service awards". Jefferson Awards.org. Jefferson Awards for Public Service. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ^ "Lifetime Honors: 1995". National Endowment for the Arts. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ "Hope Gets Freedom Award". Times-Union. Warsaw, Indiana. May 30, 1997. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ^ "Members of the Order of the Sword". Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, Montgomery, Alabama: Air University. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ "Durkan Plays the Supporting Role in the Restoration of Bob Hope Theater" (PDF). The Mohawk Group. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Castro, Tony (June 1, 2010). "Burbank airport honors namesake". Los Angeles Daily News. Jack Klunder. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Bob Hope Gallery" [1]. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ Mary Claire Campbell, "Bob Hope and His Ladies of Hope: His Mother, Wife and Our Lady of Hope Made All the Difference in His Life", October 19, 2011, [2]. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ "T-AKR USNS Bob Hope Large, Medium-speed, roll-on/roll-off ships [LMSR]". Federation of American Scientists. 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ "Boeing C-17 Dedicated to the Spirit of Medal of Honor". Warplanes Online Community. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ Ohio Remembers bob hope's Roots On His 100th Birthday - Cleveland 19.com (WOIO-TV)

- ^ "Academy Awards Database". Academy of Motion Pictures Arts & Sciences. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Pop Memories: 1890-1954. Record Research.

Sources

- Faith, William Robert (2003). Bob Hope: A Life in Comedy. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81207-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Friedrich, Otto (1986). City of Nets: A Portrait of Hollywood in 1940s. Berkeley; Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20949-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grudens, Richard (2002). The Spirit of Bob Hope: One Hundred Years, One Million Laughs. Soiux Falls, SD: Pine Hill Press. ISBN 978-1-57579-227-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lahr, John (December 21, 1998). "Profiles: The CEO of Comedy". The New Yorker: 62–79.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maltin, Leonard (1972). The Great Movie Shorts. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-517-50455-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCaffrey, Donald W. (2005). The Road to Comedy: The films of Bob Hope. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98257-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mikailian, Arin (December 5, 2012). "Bob Hope's Toluca Lake Home Hitting the Market". North Hollywood-Toluca Lake Patch. Retrieved June 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moreno, Barry (2008). Ellis Island's Famous Immigrants. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-5533-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nachman, Gerald (1998). Raised on Radio. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-40287-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - O'Dowd, John (2006). Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye: The Barbara Payton Story. Albany, GA: Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-063-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Quirk, Lawrence J. (1998). Bob Hope: The Road Well-Traveled. New York: Applause. ISBN 978-1-55783-353-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Steinbeck, John (1958). Once There Was A War. New York: Viking Press. OCLC 394412.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Mills, Robert L. (2009). The Laugh Makers: A Behind the Scenes Tribute to Bob Hope's Incredible Gag Writers. Albany, GA: Bear Manor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-323-4.

- Wilde, Larry (2000). The Great Comedians Talk About Comedy. Executive Books. ISBN 978-0-937539-51-4.

- Young, Jordan R. (1999). The Laugh Crafters: Comedy Writing in Radio and TV's Golden Age. Beverly Hills, CA: Past Times Publishing. ISBN 978-0-940410-37-4.

- Zoglin, Richard (2014). Hope: Entertainer of the Century. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-4858-7.

External links

- 1903 births

- 2003 deaths

- 20th-century American male actors

- Academy Honorary Award recipients

- Actors awarded British knighthoods

- American male film actors

- American male radio actors

- American male television actors

- American television personalities

- American people of Welsh descent

- American radio personalities

- American stand-up comedians

- American male boxers

- American centenarians

- American Roman Catholics

- English emigrants to the United States

- Burlesque performers

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Converts to Roman Catholicism

- Infectious disease deaths in California

- Deaths from pneumonia

- People from Eltham

- People from Toluca Lake, Los Angeles

- People with acquired American citizenship

- Peabody Award winners

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Kennedy Center honorees

- World Golf Hall of Fame inductees

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- National Radio Hall of Fame inductees

- Vaudeville performers

- RCA Victor artists

- Knights Commander with Star of the Order of St. Gregory the Great

- Recipients of the Order of the Sword (United States)

- Burials at San Fernando Mission Cemetery

- Paramount Pictures contract players

- Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award winners

- Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award

- California Republicans

- Las Vegas entertainers