Buryats

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 500,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 461,389[1] | |

| 45,087[2] | |

| 8,000[3] | |

| 900 | |

| 600 | |

| 400 | |

| 100 | |

| Languages | |

| Buryat, Mongolian, Russian, Chinese | |

| Religion | |

| Tibetan Buddhism ("Lamaism"), Shamanism. | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Mongols (Barga, Khalkha, Oirats, Khamnigans), Tuvans, Yakuts, Manchu, Khakas, Altay people | |

The Buryats (Buryat: Буряад, Buryaad; Template:Lang-mn), numbering approximately 500,000, are the largest indigenous group in Siberia, mainly concentrated in their homeland, the Buryat Republic, a federal subject of Russia. They are the major northern subgroup of the Mongols.[4]

Buryats share many customs with other Mongols, including nomadic herding, and erecting gers for shelter. Today, the majority of Buryats live in and around Ulan-Ude, the capital of the republic, although many live more traditionally in the countryside. They speak a central Mongolic language called Buryat.[5] According to UNESCO's 2010 edition of the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, the Buryat language is classified as severely endangered.

History

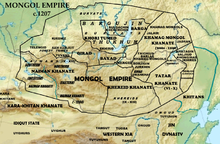

The Buryat people are descended from various Siberian and Mongol peoples that inhabited the Lake Baikal Region. Then in the 13th century the Mongolians came up and subjugated the various Buryat tribes (Bulgachin, Kheremchin) around Lake Baikal. The name "Buriyad" is mentioned as one of the forest people for the first time in The Secret History of the Mongols (possibly 1240).[6] It says Jochi, the eldest son of Genghis Khan, marched north to subjugate the Buryats in 1207.[7] The Buryats lived along the Angara River and its tributaries at this time. Meanwhile, their component, Barga, appeared both west of Baikal and in northern Buryatia's Barguzin valley. Linked also to the Bargas were the Khori-Tumed along the Arig River in eastern Khövsgöl Province and the Angara.[8] A Tumad rebellion broke out in 1217, when Genghis Khan allowed his viceroy to seize 30 Tumad maidens. Genghis Khan's commander Dorbei the Fierce of the Dörbeds smashed them in response. The Buryats joined the Oirats challenging the imperial rule of the Eastern Mongols during the Northern Yuan period in the late 14th century.[9]

Historically, the territories around Lake Baikal belonged to Mongolia, Buryats were subject to Tusheet Khan and Setsen Khan of Khalkha Mongolia. When the Russians expanded into Transbaikalia (eastern Siberia) in 1609, the Cossacks found only a small core of tribal groups speaking a Mongol dialect called Buryat and paying tribute to the Khalkha.[10] However, they were powerful enough to compel the Ket and Samoyed peoples on the Kan and the Evenks on the lower Angara to pay tribute. The ancestors of most modern Buryats were speaking a variety of Turkic-Tungusic dialects at that time.[11] In addition to genuine Buryat-Mongol tribes (Bulagad, Khori, Ekhired, Khongoodor) that merged with the Buryats, the Buryats also assimilated other groups, including some Oirats, the Khalkha, Tungus (Evenks) and others. The Khori-Barga had migrated out of the Barguzin eastward to the lands between the Greater Khingan and the Argun. Around 1594 most of them fled back to the Aga and Nerchinsk in order to escape subjection by the Daurs. The territory and people were formally annexed to the Russian state by treaties in 1689 and 1727, when the territories on both the sides of Lake Baikal were separated from Mongolia. Consolidation of modern Buryat tribes and groups took place under the conditions of the Russian state. From the middle of the 17th century to the beginning of the 20th century, the Buryat population increased from 77,000[12] (27,700[13]-60,000[14]) to 300,000.

Another estimate of the rapid growth in people referring to themselves as Buryat is based on the clan list names paying tribute in the form of a sable-skin tax. This indicates a population of about 77,000 in 1640 rising to 157,000 in 1823 and more than a million by 1950.[15]

The historical roots of the Buryat culture are related to the Mongolic peoples. After Buryatia was incorporated into Russia, it was exposed to two traditions – Buddhist and Christian. Buryats west of Lake Baikal and Olkhon (Irkut Buryats), are more "russified", and they soon abandoned nomadism for agriculture, whereas the eastern (Transbaikal) Buryats are closer to the Khalkha, may live in yurts and are mostly Buddhists. In 1741, the Tibetan branch of Buddhism was recognized as one of the official religions in Russia, and the first Buryat datsan (Buddhist monastery) was built.

The second half of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century was a time of growth for the Buryat Buddhist church (48 datsans in Buryatia in 1914). Buddhism became an important factor in the cultural development of Buryatia. Because of their skills in horsemanship and mounted combat, many were enlisted into the Amur Cossacks host. During the Russian Civil War most of the Buryats sided with the White forces of Baron Ungern-Sternberg and Ataman Semenov. They formed a sizable portion of Ungern's forces and often received favorable treatment when compared with other ethnic groups in the Baron's army. After the Revolution, most of the lamas were loyal to Soviet power. In 1925, a battle against religion and clergy in Buryatia began. Datsans were gradually closed down and the activity of the clergy was curtailed. Consequently, in the late 1930s the Buddhist clergy ceased to exist and thousands of cultural treasures were destroyed. Attempts to revive the Buddhist cult started during World War II, and it was officially re-established in 1946. A genuine revival of Buddhism has taken place since the late 1980s as an important factor in the national consolidation and spiritual rebirth.

In the 1930s, Buryat-Mongolia was one of the sites of Soviet studies aimed to disprove Nazi race theories. Among other things, Soviet physicians studied the "endurance and fatigue levels" of Russian, Buryat-Mongol, and Russian-Buryat-Mongol workers to prove that all three groups were equally able.[16]

In 1923, the Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was formed and included Baikal province (Pribaykalskaya guberniya) with Russian population. The Buryats rebelled against the communist rule and collectivization of their herds in 1929. The rebellion was quickly crushed by the Red Army with loss of 35,000 Buryats.[17] The Buryat refugees fled to Mongolia and resettled, however, only a few of them joined the Shambala rebellion there. In 1937, in an effort to disperse Buryats, Stalin's government separated a number of counties (raions) from the Buryat-Mongol Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic and formed Ust-Orda Buryat Autonomous Okrug and Agin-Buryat Autonomous Okrug; at the same time, some raions with Buryat populations were left out. Fearing Buryat nationalism, Joseph Stalin had more than 10,000 Buryats killed.[18] Moreover, Stalinist purge of Buryats spread into Mongolia, known as the incident of Lhumbee. In 1958, the name "Mongol" was removed from the name of the republic (Buryat ASSR). BASSR declared its sovereignty in 1990 and adopted the name Republic of Buryatia in 1992. The constitution of the Republic was adopted by the People's Khural in 1994, and a bilateral treaty with the Russian Federation was signed in 1995.

The Buryat national tradition is ecological by origin in that the religious and mythological ideas of the Buryat people have been based on a theology of nature. The environment has traditionally been deeply respected by Buryats due to the nomadic way of life and religious culture. The harsh climatic conditions of the region have in turn created a fragile balance between humans, society and the environment itself. This has led to a delicate approach to nature, oriented not towards its conquest but rather towards a harmonious interaction and equal partnership with it. A synthesis of Buddhism and traditional beliefs that formed a system of ecological traditions has thus constituted a major attribute of Buryat eco-culture.[19]

Subgroups

Major tribes

Other tribes

- Alair

- Ashibagad

- Atagan

- Khamnigan Buryats

- Ikinat

Notable people

- Valéry Inkijinoff, French actor

- Balzhinima Tsyrempilov, Russian archer

- Yuriy Yekhanurov, former Prime Minister of Ukraine

- Agvan Dorjiev, Buddhist monk, tutor of the 13th Dalai Lama.

- Also see Template:Ru icon List of Buryats in Russian Wikipedia for more articles.

See also

- Ust-Orda Buryat Okrug

- Agin-Buryat Okrug

- List of indigenous peoples of Russia

- Far Eastern Republic

- Buddhism in Russia

- Shamanism in Siberia

Footnotes

- ^ Ethnic groups in Russia, 2010 census, Rosstat. Retrieved 15 February 2012 Template:Ru icon

- ^ National Census 2010 Archived September 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ China Radio International, 2006

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Edition. (1977). Vol. II, p. 396. ISBN 0-85229-315-1.

- ^ "Invalid id". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ^ Erich Haenisch, Die Geheime Geschichte der Mongolen, Leipzig 1948, p. 112

- ^ Owen Lattimore-The Mongols of Manchuria, p. 165

- ^ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 61

- ^ D. T︠S︡ėvėėndorzh, Tu̇u̇khiĭn Khu̇rėėlėn (Mongolyn Shinzhlėkh Ukhaany Akademi) – Mongol Ulsyn tu̇u̇kh: XIV zuuny dund u̇eės XVII zuuny ėkhėn u̇e, p. 43

- ^ University of Pittsburgh. University Center for International Studies, Temple University-Russian history: Histoire russe, p. 464

- ^ Bowles, Gordon T. (1977). The People of Asia, pp. 278–279. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. ISBN 0-297-77360-7.

- ^ http://www.bur-culture.ru/index.php?id=news-detail&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=42&cHash=effe903f9ae6737362277ed761d6c2ca Традиционная материальная культура бурятского этноса Предбайкалья. Этногенез и расселение. Средовая культура бурят (Russian)

- ^ Buryats

- ^ П.Б. Абзаев. Буряты на рубеже XX-XXI вв. Численность, состав, занятия (Russian)

- ^ Bowles, Gordon T. (1977). The People of Asia, p. 279. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London. ISBN 0-297-77360-7.

- ^ Template:First=Francine

- ^ James Minahan-Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: S-Z, p. 345

- ^ James Stuart Olson, Lee Brigance Pappas, Nicholas Charles Pappas-An Ethnohistorical dictionary of the Russian and Soviet empires, p. 125

- ^ Esuna Dugarova. Buryatia – a symbol of Eurasia in the heartland of Baikal. UN Special (magazine)

Further reading

- Ethnic groups — Buryats

- J.G. Gruelin, Siberia.

- Pierre Simon Pallas, Sammlungen historischer Nachrichten über die mongolischen Volkerschaften (St Petersburg, 1776–1802).

- M.A. Castrén, Versuch einer buriatischen Sprachlehre (1857).

- Sir H.H. Howorth, History of the Mongols (1876–1888).

- The film A Pearl in the Forest (МОЙЛХОН) illustrates the heavy price paid by the Buryats in the 1930s during the Stalinist purges.

- Murphy, Dervla (2007) "Silverland: A Winter Journey Beyond the Urals", London, John Murray

- Natalia Zhukovskaia (Ed.) Buryaty. Moskva: Nauka, 2004 (a classic general description).

- Buryat Supermodel identifies herself as Siberian Eskimo

- Mitochondrial DNA variation in two South Siberian Aboriginal populations: implications for the genetic history of North Asia.