Cortisol: Difference between revisions

Magioladitis (talk | contribs) m Removed empty comments and/or general fixes, removed: <!-- --> using AWB (8252) |

Hamada0100 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 268: | Line 268: | ||

* [http://arthritis.about.com/od/hydrocortisone/Hydrocortisone_Dosage_Side_Effects_Drug_Interactions_Warnings.htm Dosage Side Effects and Drug Interaction Warnings] |

* [http://arthritis.about.com/od/hydrocortisone/Hydrocortisone_Dosage_Side_Effects_Drug_Interactions_Warnings.htm Dosage Side Effects and Drug Interaction Warnings] |

||

* [http://stress.about.com/od/stresshealth/a/cortisol.htm How to stay healthy with Cortisol] |

* [http://stress.about.com/od/stresshealth/a/cortisol.htm How to stay healthy with Cortisol] |

||

* [http://magicinject.com/cortisol-stress-hormone-level/ magicinject.com] |

|||

{{Hormones}} |

{{Hormones}} |

||

Revision as of 23:41, 3 September 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2011) |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682206 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral tablets, intravenous, topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.019 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

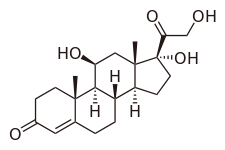

| Formula | C21H30O5 |

| Molar mass | 362.460 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Cortisol, also known more formally as hydrocortisone (INN, USAN, BAN), is a steroid hormone, more specifically a glucocorticoid, produced by the zona fasciculata of the adrenal gland.[1] It is released in response to stress and a low level of blood glucocorticoids. Its primary functions are to increase blood sugar through gluconeogenesis; suppress the immune system; and aid in fat, protein and carbohydrate metabolism.[2] It also decreases bone formation. Various synthetic forms of cortisol are used to treat a variety of diseases.

Physiology

Production and release

Cortisol is produced by the adrenal gland in the zona fasciculata,[1] the second of three layers comprising the outer adrenal cortex. This release is controlled by the hypothalamus, a part of the brain. The secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the hypothalamus triggers anterior pituitary secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH is carried by the cells to the vascular cortex, where it triggers blood secretion.

Main functions in the body

It stimulates gluconeogenesis (formation, in the liver, of glucose from certain amino acids, glycerol, lactate and/or propionate) and it activates anti-stress and anti-inflammatory pathways.

It downregulates the Interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R) on "Helper" (CD4+) T-cells. This results in the inability of Interleukin-2 to upregulate the Th2 (Humoral) immune response and results in a Th1 (Cellular) immune dominance. This results in a decrease in B-cell antibody production. Cortisol prevents the release of substances in the body that cause inflammation. This is why cortisol is used to treat conditions resulting from over activity of the B-cell mediated antibody response such as inflammatory and rheumatoid diseases, and allergies. Low-potency hydrocortisone, available over the counter in some countries, is used to treat skin problems such as rashes, eczema and others.

Cortisol plays an important role in glycogenolysis, the breaking down of glycogen to glucose-1-phosphate and glucose, in liver and muscle tissue. Glycogenolysis is stimulated by epinephrine and/or norepinephrine, however cortisol facilitates the activation of glycogen phosphorylase, which is essential for the effects of epinephrine on glycogenolysis.[3][4]

Elevated levels of cortisol, if prolonged, can lead to proteolysis and muscle wasting.[5]

Several studies have shown a lipolytic (breakdown of fat) effect of cortisol, although under some conditions, cortisol may somewhat suppress lipolysis.[6]

Another function is to decrease bone formation.

Pregnancy

During human pregnancy, increased fetal production of cortisol between weeks 30 and 32 initiates production of fetal lung surfactant to promote maturation of the lungs. In fetal lambs, glucocorticoids (principally cortisol) increase after about day 130, with lung surfactant increasing greatly, in response, by about day 135,[7] and although lamb fetal cortisol is mostly of maternal origin during the first 122 days, 88 percent or more is of fetal origin by day 136 of gestation.[8] Although the timing of fetal cortisol concentration elevation in sheep may vary somewhat, it averages about 11.8 days before the onset of labor.[9] In several livestock species (e.g. the cow, sheep, goat and pig), the surge of fetal cortisol late in gestation triggers the onset of parturition by removing the progesterone block of cervical dilation and myometrial contraction. The mechanisms yielding this effect on progesterone differ among species. In the sheep, where progesterone sufficient for maintaining pregnancy is produced by the placenta after about day 70 of gestation,[10][11] the pre-partum fetal cortisol surge induces placental enzymatic conversion of progesterone to estrogen. (The elevated level of estrogen stimulates prostaglandin secretion and oxytocin receptor development.) In the pregnant cow, where progesterone maintaining pregnancy is provided by the corpus luteum, luteolysis is induced by endometrial release of prostaglandin F2alpha, in response to fetal cortisol (and estrogen).[12]

Patterns

Diurnal cycles of cortisol levels are found in several animal species, including humans.[3] In species that exhibit such cycles, different timing of diurnal maxima and minima has been observed, not only in different species[3] but also, in some cases, within the same species.[13][14][15]

In humans, the amount of cortisol present in the blood undergoes diurnal variation; the level peaks in the early morning (approximately 8 am) and reaches its lowest level at about midnight-4 am, or three to five hours after the onset of sleep. Information about the light/dark cycle is transmitted from the retina to the paired suprachiasmatic nuclei in the hypothalamus. This pattern is not present at birth; estimates of when it begins vary from two weeks to nine months of age.[16]

Changed patterns of serum cortisol levels have been observed in connection with abnormal ACTH levels, clinical depression, psychological stress, and physiological stressors such as hypoglycemia, illness, fever, trauma, surgery, fear, pain, physical exertion, or temperature extremes. Cortisol levels may also differ for individuals with autism or Asperger's syndrome.[17]

There is also significant individual variation, although a given person tends to have consistent rhythms.[citation needed]

Ultradian as well as circadian cycles of cortisol secretion have been observed, e.g. a cycle period of about 2 h in cattle[18] and about 1 h in sheep.[13]

Normal levels

Normal values indicated in the following tables pertain to humans. (Normals vary among species.)

| Reference ranges for blood plasma content of free cortisol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit |

| 09:00 am | 140[19] | 700[19] | nmol/L |

| 5[20] | 25[20] | μg/dL | |

| Midnight | 80[19] | 350[19] | nmol/L |

| 2.9[20] | 13[20] | μg/dL | |

Using the molecular weight of 362.460 g/mole, the conversion factor from µg/dl to nmol/L is approximately 27.6; thus, 10 µg/dl is approximately equal to 276 nmol/L.

| Reference ranges for urinalysis of free cortisol | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Unit | |

| 28[21] or 30[22] | 280[21] or 490[22] | nmol/24h | |

| 10[23] or 11[24] | 100[23] or 176[24] | µg/24 h | |

Effects

Cortisol is released in response to stress, acting to restore homeostasis. However, prolonged cortisol secretion (which may be due to chronic stress or the excessive secretion seen in Cushing's syndrome) results in significant physiological changes.[1]

- Insulin

Cortisol counteracts insulin, contributes to hyperglycemia-causing hepatic gluconeogenesis[25] and inhibits the peripheral utilization of glucose (insulin resistance)[25] by decreasing the translocation of glucose transporters (especially GLUT4) to the cell membrane.[26][27] However, cortisol increases glycogen synthesis (glycogenesis) in the liver.[28] The permissive effect of cortisol on insulin action in liver glycogenesis is observed in hepatocyte culture in the laboratory, although the mechanism for this is unknown.

- Collagen

In laboratory rats, cortisol-induced collagen loss in the skin is ten times greater than in any other tissue.[29][30] Cortisol (as opticortinol) may inversely inhibit IgA precursor cells in the intestines of calves.[31] Cortisol also inhibits IgA in serum, as it does IgM; however, it is not shown to inhibit IgE.[32]

- Gastric and renal secretion

Cortisol stimulates gastric-acid secretion.[33] Cortisol's only direct effect on the hydrogen ion excretion of the kidneys is to stimulate the excretion of ammonium ions by deactivating the renal glutaminase enzyme.[34] Net chloride secretion in the intestines is inversely decreased by cortisol in vitro (methylprednisolone).[35]

- Sodium

Cortisol inhibits sodium loss through the small intestine of mammals.[36] Sodium depletion, however, does not affect cortisol levels[37] so cortisol cannot be used to regulate serum sodium. Cortisol's original purpose may have been sodium transport. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that freshwater fish utilize cortisol to stimulate sodium inward, while saltwater fish have a cortisol-based system for expelling excess sodium.[38]

- Potassium

A sodium load augments the intense potassium excretion by cortisol; corticosterone is comparable to cortisol in this case.[28] In order for potassium to move out of the cell, cortisol moves an equal number of sodium ions into the cell.[39] This should make pH regulation much easier (unlike the normal potassium-deficiency situation, in which two sodium ions move in for each three potassium ions that move out—closer to the deoxycorticosterone effect). Nevertheless, cortisol consistently causes serum alkalosis; in a deficiency, serum pH does not change. The purpose of this may be to reduce serum pH to an optimum value for some immune enzymes during infection, when cortisol declines. Potassium is also blocked from loss in the kidneys by a decline in cortisol (9 alpha fluorohydrocortisone).[40]

- Water

Cortisol acts as a diuretic hormone, controlling one-half of intestinal diuresis;[36] it has also been shown to control kidney diuresis in dogs. The decline in water excretion following a decline in cortisol (dexamethasone) in dogs is probably due to inverse stimulation of antidiuretic hormone (ADH or arginine vasopressin), which is not overridden by water loading.[41] Humans and other animals also use this mechanism.[42]

- Copper

Cortisol stimulates many copper enzymes (often to 50% of their total potential), probably to increase copper availability for immune purposes.[43]: 337 This includes lysyl oxidase, an enzyme which is used to cross-link collagen and elastin.[43]: 334 Especially valuable for immune response is cortisol's stimulation of the superoxide dismutase,[44] since this copper enzyme is almost certainly used by the body to permit superoxides to poison bacteria. Cortisol causes an inverse four- or fivefold decrease of metallothionein (a copper storage protein) in mice;[45] however, rodents do not synthesize cortisol themselves. This may be to furnish more copper for ceruloplasmin synthesis or to release free copper. Cortisol has an opposite effect on aminoisobuteric acid than on the other amino acids.[46] If alpha-aminoisobuteric acid is used to transport copper through the cell wall, this anomaly might be explained.

- Immune system

Cortisol can weaken the activity of the immune system. Cortisol prevents proliferation of T-cells by rendering the interleukin-2 producer T-cells unresponsive to interleukin-1 (IL-1), and unable to produce the T-cell growth factor.[47] Cortisol also has a negative-feedback effect on interleukin-1.[48] IL-1 must be especially useful in combating some diseases; however, endotoxic bacteria have gained an advantage by forcing the hypothalamus to increase cortisol levels (forcing the secretion of CRH hormone, thus antagonizing IL-1). The suppressor cells are not affected by glucosteroid response-modifying factor (GRMF),[49] so the effective setpoint for the immune cells may be even higher than the setpoint for physiological processes (reflecting leukocyte redistribution to lymph nodes, bone marrow, and skin). Rapid administration of corticosterone (the endogenous Type I and Type II receptor agonist) or RU28362 (a specific Type II receptor agonist) to adrenalectomized animals induced changes in leukocyte distribution. Natural killer cells are not affected by cortisol.[50]

- Bone metabolism

Cortisol reduces bone formation, favoring long-term development of osteoporosis. It transports potassium out of cells in exchange for an equal number of sodium ions (see above).[39] This can trigger the hyperkalemia of metabolic shock from surgery. Cortisol also reduces calcium absorption in the intestine.[51]

- Memory

Cortisol works with epinephrine (adrenaline) to create memories of short-term emotional events; this is the proposed mechanism for storage of flash bulb memories, and may originate as a means to remember what to avoid in the future. However, long-term exposure to cortisol damages cells in the hippocampus;[52] this damage results in impaired learning. Furthermore, it has been shown that cortisol inhibits memory retrieval of already stored information.[53][54]

- Additional effects

- Increases blood pressure by increasing the sensitivity of the vasculature to epinephrine and norepinephrine; in the absence of cortisol, widespread vasodilation occurs [citation needed]

- Inhibits secretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), resulting in feedback inhibition of ACTH (Adrenocorticotropic hormone or corticotropin) secretion. Some researchers believe that this normal feedback system may become dysregulated when animals are exposed to chronic stress[citation needed]

- Shuts down the reproductive system, resulting in an increased chance of miscarriage and (in some cases) temporary infertility. Fertility returns after cortisol levels return to normal.[56]

- Has anti-inflammatory properties, reducing histamine secretion and stabilizing lysosomal membranes. Stabilization of lysosomal membranes prevents their rupture, preventing damage to healthy tissues [citation needed]

- Stimulates hepatic detoxification by inducing tryptophan oxygenase (reducing serotonin levels in the brain), glutamine synthase (reducing glutamate and ammonia levels in the brain), cytochrome P-450 hemoprotein (mobilizing arachidonic acid), and metallothionein (reducing heavy metals in the body)[citation needed]

- In addition to cortisol's effects in binding to the glucocorticoid receptor, because of its molecular similarity to aldosterone it also binds to the mineralocorticoid receptor. Aldosterone and cortisol have a similar affinity for the mineralocorticoid receptor; however, glucocorticoids circulate at roughly 100 times the level of mineralocorticoids. An enzyme exists in mineralocorticoid target tissues to prevent overstimulation by glucocorticoids and allow selective mineralocorticoid action. This enzyme—11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type II (Protein:HSD11B2)—catalyzes the deactivation of glucocorticoids to 11-dehydro metabolites[citation needed]

- There are potential links between cortisol, appetite and obesity.[57]

Binding

Most serum cortisol (all but about 4%) is bound to proteins, including corticosteroid binding globulin (CBG) and serum albumin. Free cortisol passes easily through cellular membranes, where they bind intracellular cortisol receptors.[58]

Regulation

The primary control of cortisol is the pituitary gland peptide, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). ACTH probably controls cortisol by controlling the movement of calcium into the cortisol-secreting target cells.[59] ACTH is in turn controlled by the hypothalamic peptide corticotropin releasing hormone (CRH), which is under nervous control. CRH acts synergistically with arginine vasopressin, angiotensin II, and epinephrine.[60] (In swine, which do not produce arginine vasopressin, lysine vasopressin acts synergistically with CRH.[61]) When activated macrophages start to secrete interleukin-1 (IL-1), which synergistically with CRH increases ACTH,[48] T-cells also secrete glucosteroid response modifying factor (GRMF or GAF) as well as IL-1; both increase the amount of cortisol required to inhibit almost all the immune cells.[49] Immune cells then assume their own regulation, but at a higher cortisol setpoint. The increase in cortisol in diarrheic calves is minimal over healthy calves, however, and falls over time.[62] The cells do not lose all their fight-or-flight override because of interleukin-1's synergism with CRH. Cortisol even has a negative feedback effect on interleukin-1[48]—especially useful for those diseases which gain an advantage by forcing the hypothalamus to secrete too much CRH, such as those caused by endotoxic bacteria. The suppressor immune cells are not affected by GRMF,[49] so the immune cells' effective setpoint may be even higher than the setpoint for physiological processes. GRMF (known as GAF in this reference) primarily affects the liver (rather than the kidneys) for some physiological processes.[63]

High potassium media (which stimulates aldosterone secretion in vitro) also stimulate cortisol secretion from the fasciculata zone of canine adrenals [64] — unlike corticosterone, upon which potassium has no effect.[65] Potassium loading also increases ACTH and cortisol in humans.[66] This is probably the reason why potassium deficiency causes cortisol to decline (as mentioned) and causes a decrease in conversion of 11-deoxycortisol to cortisol.[67] This may also have a role in rheumatoid-arthritis pain; cell potassium is always low in RA.[68]

Factors generally reducing cortisol levels

- Magnesium supplementation decreases serum cortisol levels after aerobic exercise,[69][70] but not after resistance training.[71]

- Omega 3 fatty acids have a dose-dependent effect[72] in slightly reducing cortisol release influenced by mental stress,[73] suppressing the synthesis of interleukin-1 and -6 and enhancing the synthesis of interleukin-2; the former promotes higher CRH release. Omega 6 fatty acids, on the other hand, have an inverse effect on interleukin synthesis.[citation needed]

- Music therapy can reduce cortisol levels in certain situations.[74]

- Massage therapy can reduce cortisol.[75]

- Laughing, and the experience of humour, can lower cortisol levels.[76]

- Soy-derived phosphatidylserine interacts with cortisol; the correct dose, however, is unclear.[77][78]

- Black tea may hasten recovery from a high-cortisol condition.[79][80]

- Regular dancing has been shown to lead to significant decreases in salivary cortisol concentrations.[81]

Factors generally increasing cortisol levels

- Caffeine may increase cortisol levels.[82]

- Sleep deprivation[83]

- Intense (high VO2 max) or prolonged physical exercise stimulates cortisol release to increase gluconeogenesis and maintain blood glucose.[84] Proper nutrition[85] and high-level conditioning[86] can help stabilize cortisol release.

- The Val/Val variation of the BDNF gene in men, and the Val/Met variation in women, are associated with increased salivary cortisol in a stressful situation.[87]

- Hypoestrogenism and melatonin supplementation increase cortisol levels in postmenopausal women.[88]

- Burnout is associated with higher cortisol levels.[89]

- Severe trauma or stressful events can elevate cortisol levels in the blood for prolonged periods.[90][91]

- Subcutaneous adipose tissue regenerates cortisol from cortisone.[92]

- Anorexia nervosa may be associated with increased cortisol levels.[93]

- The serotonin receptor gene 5HTR2C is associated with increased cortisol production in men.[94]

- Commuting increases cortisol levels relative to the length of the trip, its predictability and the amount of effort involved.[95]

- Stimuli associated with sexual intercourse can increase cortisol levels in gilts (a young female pig that has not produced her first litter).[96]

- Severe calorie restriction causes elevated baseline levels of cortisol.[97]

Clinical chemistry

- Hypercortisolism: Excessive levels of cortisol in the blood. (See Cushing's syndrome.)

- Hypocortisolism (adrenal insufficiency): Insufficient levels of cortisol in the blood.

The relationship between cortisol and ACTH, and some consequent conditions, are as follows:

| Plasma ACTH | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ | ↑ | ||

| Plasma Cortisol | ↑ | Primary hypercortisolism (Cushing's syndrome) | Secondary hypercortisolism (pituitary or ectopic tumor, Cushing's disease, pseudo-Cushing's syndrome) |

| ↓ | Secondary hypocortisolism (pituitary tumor, Sheehan's syndrome) | Primary hypocortisolism (Addison's disease, Nelson's syndrome) | |

A 2010 study has found that serum cortisol predicts increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome.[98][99]

Pharmacology

Hydrocortisone is the pharmaceutical term for cortisol used in oral administration, intravenous injection or topical application. It is used as an immunosuppressive drug, given by injection in the treatment of severe allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis and angioedema, in place of prednisolone in patients who need steroid treatment but cannot take oral medication, and perioperatively in patients on longterm steroid treatment to prevent Addisonian crisis. It may be used topically for allergic rashes, eczema, psoriasis and certain other inflammatory skin conditions. It may also be injected into inflamed joints resulting from diseases such as gout.

Compared to hydrocortisone, prednisolone is about four times as strong and dexamethasone about forty times as strong, in their anti-inflammatory effect. [citation needed] For side effects, see corticosteroid and prednisolone.

Topical hydrocortisone creams and ointments are available in most countries without prescription in strengths ranging from 0.05% to 2.5% (depending on local regulations) with stronger forms available by prescription only. Covering the skin after application increases the absorption and effect. Such enhancement is sometimes prescribed, but otherwise should be avoided to prevent overdose and systemic impact.

Advertising for the dietary supplement CortiSlim originally (and falsely) claimed that it contributed to weight loss by blocking cortisol. The manufacturer was fined $12 million by the Federal Trade Commission in 2007 for false advertising, and no longer claims in their marketing that CortiSlim is a cortisol antagonist.[100]

Biochemistry

Biosynthesis

Cortisol is synthesized from cholesterol. Synthesis takes place in the zona fasciculata of the adrenal cortex. (The name cortisol is derived from cortex.) While the adrenal cortex also produces aldosterone (in the zona glomerulosa) and some sex hormones (in the zona reticularis), cortisol is its main secretion in humans and several other species. (However, in cattle, corticosterone levels may approach[101] or exceed.[3] cortisol levels.). The medulla of the adrenal gland lies under the cortex, mainly secreting the catecholamines adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) under sympathetic stimulation.

The synthesis of cortisol in the adrenal gland is stimulated by the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland with adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); ACTH production is in turn stimulated by corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which is released by the hypothalamus. ACTH increases the concentration of cholesterol in the inner mitochondrial membrane, via regulation of the STAR (steroidogenic acute regulatory) protein. It also stimulates the main rate-limiting step in cortisol synthesis, in which cholesterol is converted to pregnenolone and catalyzed by Cytochrome P450SCC (side chain cleavage enzyme).[102]

Metabolism

Cortisol is metabolized by the 11-beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase system (11-beta HSD), which consists of two enzymes: 11-beta HSD1 and 11-beta HSD2.

- 11-beta HSD1 utilizes the cofactor NADPH to convert biologically-inert cortisone to biologically-active cortisol

- 11-beta HSD2 utilizes the cofactor NAD+ to convert cortisol to cortisone

Overall, the net effect is that 11-beta HSD1 serves to increase the local concentrations of biologically-active cortisol in a given tissue; 11-beta HSD2 serves to decrease local concentrations of biologically-active cortisol.

Cortisol is also metabolized into 5-alpha tetrahydrocortisol (5-alpha THF) and 5-beta tetrahydrocortisol (5-beta THF), reactions for which 5-alpha reductase and 5-beta reductase are the rate-limiting factors respectively. 5-beta reductase is also the rate-limiting factor in the conversion of cortisone to tetrahydrocortisone (THE).

An alteration in 11-beta HSD1 has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of obesity, hypertension, and insulin resistance known as metabolic syndrome.[103]

An alteration in 11-beta HSD2 has been implicated in essential hypertension and is known to lead to the syndrome of apparent mineralocorticoid excess (SAME).[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b c Scott E (2011-09-22). "Cortisol and Stress: How to Stay Healthy". About.com. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ^ Hoehn K, Marieb EN (2010). Human Anatomy & Physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-321-60261-7.

- ^ a b c d Martin PA, Crump MH (2003). "The adrenal gland". In Dooley MP, Pineda MH (ed.). McDonald's veterinary endocrinology and reproduction (5th ed.). Ames, Iowa: Iowa State Press. ISBN 0-8138-1106-6.

- ^ Coderre L, Srivastava AK, Chiasson JL (1991). "Role of glucocorticoid in the regulation of glycogen metabolism in skeletal muscle". Am. J. Physiol. 260 (6 Pt 1): E927–32. PMID 1905485.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simmons PS, Miles JM, Gerich JE, Haymond MW (1984). "Increased proteolysis. An effect of increases in plasma cortisol within the physiologic range". J. Clin. Invest. 73 (2): 412–20. doi:10.1172/JCI111227. PMC 425032. PMID 6365973.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Djurhuus CB, Gravholt CH, Nielsen S, Mengel A, Christiansen JS, Schmitz OE, Møller N (2002). "Effects of cortisol on lipolysis and regional interstitial glycerol levels in humans". Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 283 (1): E172–7. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00544.2001. PMID 12067858.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mescher EJ, Platzker AC, Ballard PL, Kitterman JA, Clements JA, Tooley WH (1975). "Ontogeny of tracheal fluid, pulmonary surfactant, and plasma corticoids in the fetal lamb". J Appl Physiol. 39 (6): 1017–21. PMID 2573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hennessy DP, Coghlan JP, Hardy KJ, Scoggins BA, Wintour EM (1982). "The origin of cortisol in the blood of fetal sheep". J. Endocrinol. 95 (1): 71–9. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0950071. PMID 7130892.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Magyar DM, Fridshal D, Elsner CW, Glatz T, Eliot J, Klein AH, Lowe KC, Buster JE, Nathanielsz PW (1980). "Time-trend analysis of plasma cortisol concentrations in the fetal sheep in relation to parturition". Endocrinology. 107 (1): 155–9. doi:10.1210/endo-107-1-155. PMID 7379742.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ricketts AP, Flint AP (1980). "Onset of synthesis of progesterone by ovine placenta". J. Endocrinol. 86 (2): 337–47. PMID 6933207.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Al-Gubory KH, Solari A, Mirman B (1999). "Effects of luteectomy on the maintenance of pregnancy, circulating progesterone concentrations and lambing performance in sheep". Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 11 (6): 317–22. PMID 10972299.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jainudeen MR, Hafez ESE (2000). "Gestation, prenatal physiology, and parturition". In Hafez ESE, Hafez B (ed.). Reproduction in farm animals. Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 140–155. ISBN 0-683-30577-8.

- ^ a b Fulkerson WJ, Tang BY (1979). "Ultradian and circadian rhythms in the plasma concentration of cortisol in sheep". J. Endocrinol. 81 (1): 135–41. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0810135. PMID 469453.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mesbah S, Brudieux R (1982). "Diurnal variation of plasma concentrations of cortisol, aldosterone and electrolytes in the ram". Horm. Metab. Res. 14 (6): 320–3. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1019005. PMID 6889565.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Simonetta G, Walker DW, McMillen IC (1991). "Effect of feeding on the diurnal rhythm of plasma cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone concentrations in the pregnant ewe and sheep fetus". Exp. Physiol. 76 (2): 219–29. PMID 1647800.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Weerth C, Zijl RH, Buitelaar JK (2003). "Development of cortisol circadian rhythm in infancy". Early Hum. Dev. 73 (1–2): 39–52. doi:10.1016/S0378-3782(03)00074-4. PMID 12932892.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Asperger's stress hormone 'link'". BBC News Online. 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Lefcourt AM, Bitman J, Kahl S, Wood DL (1993). "Circadian and ultradian rhythms of peripheral cortisol concentrations in lactating dairy cows". J. Dairy Sci. 76 (9): 2607–12. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(93)77595-5. PMID 8227661.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Biochemistry Reference Ranges at Good Hope Hospital Retrieved 8 November 2009[dead link]

- ^ a b c d Derived from molar values using molar mass of 362 g/mol

- ^ a b Converted from µg/24h, using molar mass of 362.460 g/mol

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10342356, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10342356instead. - ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Cortisol - urine

- ^ a b Converted from nmol/24h, using molar mass of 362.460 g/mol

- ^ a b Brown DF, Brown DD (2003). USMLE Step 1 Secrets: Questions You Will Be Asked on USMLE Step 1. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus. p. 63. ISBN 1-56053-570-9.

- ^ King MB (2005). Lange Q & A. New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. ISBN 0-07-144578-1.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17426391, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17426391instead. - ^ a b Baynes J, Dominiczak M (2009). Medical biochemistry. Mosby Elsevier. ISBN 0-323-05371-8. Cite error: The named reference "isbn0-323-05371-8" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Houck JC, Sharma VK, Patel YM, Gladner JA (1968). "Induction of collagenolytic and proteolytic activities by anti-inflammatory drugs in the skin and fibroblast". Biochem. Pharmacol. 17 (10): 2081–90. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(68)90182-2. PMID 4301453.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Manchester KL (1964). Allison HN, J B Munro JB (ed.). Induction of collagenolytic and proteolytic activities by anti-inflammatory drugs in the skin and fibroblast |. Mammalian Protein Metabolism. Vol. 1. p. 229.

- ^ Husband AJ, Brandon MR, Lascelles AK (1973). "The effect of corticosteroid on absorption and endogenous production of immunoglobulins in calves". Aust J Exp Biol Med Sci. 51 (5): 707–10. doi:10.1038/icb.1973.67. PMID 4207041.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Posey WC, Nelson HS, Branch B, Pearlman DS (1978). "The effects of acute corticosteroid therapy for asthma on serum immunoglobulin levels". J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 62 (6): 340–8. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(78)90134-3. PMID 712020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Soffer LJ, Dorfman RI, Gabrilove JL (1961). The Human Adrenal Gland. Lea & Febiger.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kokshchuk GI, Pakhmurnyi BA (1979). "Role of Glucocorticoids in Regulation of the Acid-Excreting Function of the Kidneys". Fiziol. Z H SSR I.M.I.M. Sechenova. 65 (6): 340–8. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(78)90134-3. PMID 712020.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Tai YH, Decker RA, Marnane WG, Charney AN, Donowitz M (1981). "Effects of methylprednisolone on electrolyte transport by in vitro rat ileum". Am. J. Physiol. 240 (5): G365–70. PMID 6112881.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Sandle GI, Keir MJ, Record CO (1981). "The effect of hydrocortisone on the transport of water, sodium, and glucose in the jejunum. Perfusion studies in normal subjects and patients with coeliac disease". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 16 (5): 667–71. doi:10.3109/00365528109182028. PMID 7323700.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mason PA, Fraser R, Morton JJ, Semple PF, Wilson A (1977). "The effect of sodium deprivation and of angiotensin II infusion on the peripheral plasma concentrations of 18-hydroxycorticosterone, aldosterone and other corticosteroids in man". J. Steroid Biochem. 8 (8): 799–804. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(77)90086-3. PMID 592808.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gorbman A, Dickhoff WW, Vigna SR, Clark NB, Muller AF (1983). Comparative endocrinology. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-06266-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Knight RP, Kornfeld DS, Glaser GH, Bondy PK (1955). "Effects of intravenous hydrocortisone on electrolytes of serum and urine in man". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 15 (2): 176–81. doi:10.1210/jcem-15-2-176. PMID 13233328.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barger AC, Berlin RD, Tulenko JF (1958). "Infusion of aldosterone, 9-alpha-fluorohydrocortisone and antidiuretic hormone into the renal artery of normal and adrenalectomized, unanesthetized dogs: effect on electrolyte and water excretion". Endocrinology. 62 (6): 804–15. doi:10.1210/endo-62-6-804. PMID 13548099.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boykin J, DeTorrenté A, Erickson A, Robertson G, Schrier RW (1978). "Role of plasma vasopressin in impaired water excretion of glucocorticoid deficiency". J. Clin. Invest. 62 (4): 738–44. doi:10.1172/JCI109184. PMC 371824. PMID 701472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dingman JF, Gonzalez-Auvert Ahmed ABJ, Akinura A (1965). "Plasma Antidiuretic Hormone in Adrenal Insufficiency". J. Clin. Invest. 44: 1041.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Weber CE (1984). "Copper response to rheumatoid arthritis". Med. Hypotheses. 15 (4): 333–48. doi:10.1016/0306-9877(84)90150-6. PMID 6152006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Flohe L, Beckman R, Giertz H, Loschen G (1985). "Oxygen Centered Free Radicals as Mediators of Inflammation". In Sies H (ed.). Oxidative stress. London: Orlando. p. 405. ISBN 0-12-642760-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piletz JE, Herschman HR (1983). "Hepatic metallothionein synthesis in neonatal Mottled-Brindled mutant mice". Biochem. Genet. 21 (5–6): 465–75. doi:10.1007/BF00484439. PMID 6870774.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chambers JW, Georg RH, Bass AD (1965). "Effect of hydrocortisone and insulin on uptake of alpha-aminoisobutyric acid by isolated perfused rat liver". Mol. Pharmacol. 1 (1): 66–76. PMID 5835080.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Palacios R, Sugawara I (1982). "Hydrocortisone abrogates proliferation of T cells in autologous mixed lymphocyte reaction by rendering the interleukin-2 Producer T cells unresponsive to interleukin-1 and unable to synthesize the T-cell growth factor". Scand. J. Immunol. 15 (1): 25–31. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.1982.tb00618.x. PMID 6461917.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Besedovsky HO, Del Rey A, Sorkin E (1986). "Integration of Activated Immune Cell Products in Immune Endocrine Feedback Circuits". In Oppenheim JJ, Jacobs DM (ed.). Leukocytes and Host Defense. Progress in Leukocyte Biology. Vol. 5. New York: Alan R. Liss. p. 200.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Fairchild SS, Shannon K, Kwan E, Mishell RI (1984). "T cell-derived glucosteroid response-modifying factor (GRMFT): a unique lymphokine made by normal T lymphocytes and a T cell hybridoma". J. Immunol. 132 (2): 821–7. PMID 6228602.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Onsrud M, Thorsby E (1981). "Influence of in vivo hydrocortisone on some human blood lymphocyte subpopulations. I. Effect on natural killer cell activity". Scand. J. Immunol. 13 (6): 573–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3083.1981.tb00171.x. PMID 7313552.

- ^ Deutsch E (1978). "[Pathogenesis of thrombocytopenia. 2. Distribution disorders, pseudo-thrombocytopenias]". Fortschr. Med. (in German). 96 (14): 761–2. doi:10.1073/pnas.79.11.3542. PMID 346457.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ McAuley MT, Kenny RA, Kirkwood TB, Wilkinson DJ, Jones JJ, Miller VM (2009). "A mathematical model of aging-related and cortisol induced hippocampal dysfunction". BMC Neurosci. 10: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-26. PMC 2680862. PMID 19320982.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, McGaugh JL (1998). "Stress and glucocorticoids impair retrieval of long-term spatial memory". Nature. 394 (6695): 787–90. doi:10.1038/29542. PMID 9723618.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de Quervain DJ, Roozendaal B, Nitsch RM, McGaugh JL, Hock C (2000). "Acute cortisone administration impairs retrieval of long-term declarative memory in humans". Nat. Neurosci. 3 (4): 313–4. doi:10.1038/73873. PMID 10725918.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kennedy, Ron. "Cortisol (Hydrocortisone)". The Doctors' Medical Library. Retrieved 2012-07-02.

- ^ Nelson RF (2011). An Introduction to Behavioral Endocrinology, Fourth Edition. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates Inc. ISBN 0-87893-620-3.

- ^ Maglione-Garves CA, Kravitz L, Schneider S. "Stress Cortisol Connection: Tips on Managing Stress and Weight". University of New Mexico. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boron WF, Boulpaep EL (2011). Medical Physiology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. ISBN 1-4377-1753-5.

- ^ Davies E., Keyon C.J., Fraser R. (1985). "The role of calcium ions in the mechanism of ACTH stimulation of cortisol synthesis". Steroids. 45 (6): 557. doi:10.1016/0039-128X(85)90019-4. PMID 3012830.

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Plotsky PM, Otto S, Sapolsky RM (1986). "Inhibition of immunoreactive corticotropin-releasing factor secretion into the hypophysial-portal circulation by delayed glucocorticoid feedback". Endocrinology. 119 (3): 1126–30. doi:10.1210/endo-119-3-1126. PMID 3015567.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Minton JE, Parsons KM (1993). "Adrenocorticotropic hormone and cortisol response to corticotropin-releasing factor and lysine vasopressin in pigs". J. Anim. Sci. 71 (3): 724–9. PMID 8385088.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dvorak M (1971). "Plasma 17-Hydroxycorticosteroid Levels in Healthy and Diarrheic Calves". British Veterinarian Journal. 127: 372.

- ^ Stith RD, McCallum RE (1986). "General effect of endotoxin on glucocorticoid receptors in mammalian tissues". Circ. Shock. 18 (4): 301–9. PMID 3084123.

- ^ Mikosha AS, Pushkarov IS, Chelnakova IS, Remennikov GYA (1991). "Potassium Aided Regulation of Hormone Biosynthesis in Adrenals of Guinea Pigs Under Action of Dihydropyridines: Possible Mechanisms of Changes in Steroidogenesis Induced by 1,4, Dihydropyridines in Dispersed Adrenocorticytes". Fiziol. [Kiev]. 37: 60.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mendelsohn FA, Mackie C (1975). "Relation of intracellular K+ and steroidogenesis in isolated adrenal zona glomerulosa and fasciculata cells". Clin Sci Mol Med. 49 (1): 13–26. PMID 168026.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ueda Y, Honda M, Tsuchiya M, Watanabe H, Izumi Y, Shiratsuchi T, Inoue T, Hatano M (1982). "Response of plasma ACTH and adrenocortical hormones to potassium loading in essential hypertension". Jpn. Circ. J. 46 (4): 317–22. doi:10.1253/jcj.46.317. PMID 6283190.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bauman K, Muller J (1972). "Effect of potassium on the final status of aldosterone biosynthesis in the rat. I 18-hydroxylation and 18hydroxy dehydrogenation. II beta-hydroxylation". Acta Endocrin. Copenh. 69: I 701–717, II 718–730.

- ^ LaCelle PL; et al. (1964). "An investigation of total body potassium in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Rheumatism Association, Arthritis and Rheumatism. 7: 321.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6527092, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=6527092instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9794094, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9794094instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1186/1550-2783-1-2-12, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1186/1550-2783-1-2-12instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1832814, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1832814instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12909818, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12909818instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15086180, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15086180instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16162447, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16162447instead. - ^ Berk LS, Tan SA, Berk D (2008). "Cortisol and Catecholamine stress hormone decrease is associated with the behavior of perceptual anticipation of mirthful laughter". The FASEB Journal. 22 (1): 946.11.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15512856, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15512856instead. - ^ Starks MA, Starks SL, Kingsley M, Purpura M, Jäger R (2008). "The effects of phosphatidylserine on endocrine response to moderate intensity exercise". J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 5: 11. doi:10.1186/1550-2783-5-11. PMC 2503954. PMID 18662395.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Black tea 'soothes away stress'". BBC News Online. 2006-10-04. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17013636, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17013636instead. - ^ Quiroga MC, Bongard S, Kreutz G (2009). "Emotional and Neurohumoral Responses to Dancing Tango Argentino: The Effects of Music and Partner". Music and Medicine. 1 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1177/1943862109335064.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lovallo WR, Farag NH, Vincent AS, Thomas TL, Wilson MF (2006). "Cortisol responses to mental stress, exercise, and meals following caffeine intake in men and women". Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 83 (3): 441–7. doi:10.1016/j.pbb.2006.03.005. PMC 2249754. PMID 16631247.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Leproult R, Copinschi G, Buxton O, Van Cauter E (1997). "Sleep loss results in an elevation of cortisol levels the next evening". Sleep. 20 (10): 865–70. PMID 9415946.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robson PJ, Blannin AK, Walsh NP, Castell LM, Gleeson M (1999). "Effects of exercise intensity, duration and recovery on in vitro neutrophil function in male athletes". Int J Sports Med. 20 (2): 128–35. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971106. PMID 10190775.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16572599, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16572599instead. - ^ Kraemer WJ, Spiering BA, Volek JS, Martin GJ, Howard RL, Ratamess NA, Hatfield DL, Vingren JL, Ho JY, Fragala MS, Thomas GA, French DN, Anderson JM, Häkkinen K, Maresh CM (2009). "Recovery from a national collegiate athletic association division I football game: muscle damage and hormonal status". J Strength Cond Res. 23 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1519/JSC.0b013e31819306f2. PMID 19077734.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18990498, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18990498instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9181519, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9181519instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.015, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.02.015instead. - ^ Smith JL, Gropper SAS, Groff JL (2009). Advanced nutrition and human metabolism. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 247. ISBN 0-495-11657-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moberg GP, Mench JA (2000). The biology of animal stress: basic principles and implications for animal welfare. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CABI Pub. p. 377. ISBN 0-85199-359-1.

- ^ Stimson RH, Andersson J, Andrew R, Redhead DN, Karpe F, Hayes PC, Olsson T, Walker BR (2009). "Cortisol release from adipose tissue by 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in humans". Diabetes. 58 (1): 46–53. doi:10.2337/db08-0969. PMC 2606892. PMID 18852329.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haas VK, Kohn MR, Clarke SD, Allen JR, Madden S, Müller MJ, Gaskin KJ (2009). "Body composition changes in female adolescents with anorexia nervosa". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 89 (4): 1005–10. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.26958. PMID 19211813.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brummett BH, Kuhn CM, Boyle SH, Babyak MA, Siegler IC, Williams RB (2012). "Cortisol responses to emotional stress in men: association with a functional polymorphism in the 5HTR2C gene". Biol Psychol. 89 (1): 94–8. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.09.013. PMC 3245751. PMID 21967853.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Impact of Mode and Mode Transfer on Commuter Stress, The Montclair Connection" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Kotwica G, Franczak A, Okrasa S, Koziorowski M, Kurowicka B (2002). "Effects of mating stimuli and oxytocin on plasma cortisol concentration in gilts". Reprod Biol. 2 (1): 25–37. PMID 14666160.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fichter MM, Pirke KM, Holsboer F (1986). "Weight loss causes neuroendocrine disturbances: experimental study in healthy starving subjects". Psychiatry Res. 17 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(86)90042-9. PMID 3080766.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Serum cortisol predicts increased cardiovascular mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome". Endocrine-abstracts.org. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1530/eje.1.01959, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1530/eje.1.01959instead. - ^ Iwata, Edward (5 January 2007). "Diet pill sellers fined $25M". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ^ Willett LB, Erb RE (1972). "Short term changes in plasma corticoids in dairy cattle". J. Anim. Sci. 34 (1): 103–11. PMID 5062063.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Margioris AN, Tsatsanis C (2011). "ACTH Action on the Adrenal". In Chrousos G (ed.). Adrenal physiology and diseases. Endotext.org.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15466942, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15466942instead.