Hentaigana

| Hentaigana 変体仮名 | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 800 – 1900 CE; minor use at present |

| Languages | Japanese and Okinawan |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Katakana, Hiragana |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Hira (410), Hiragana |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Hiragana |

|

| Japanese writing |

|---|

| Components |

| Uses |

| Transliteration |

In the Japanese writing system, hentaigana (変体仮名, "variant kana")[a] are obsolete or nonstandard hiragana. They include both stylistic variants of current hiragana and distinct alternative hiragana characters. Today, with a few exceptions, there is only one hiragana for each of the fifty consonant–vowel sequences (moras) in Japanese. However, traditionally there were generally several more-or-less interchangeable hiragana for each. A 1900 script reform[b] ordained that only one selected character be used for each mora, with the rest deemed hentaigana. Although not normally used in publication, hentaigana are still used in shop signs and brand names to create a traditional or antiquated air.

Hiragana originate in man'yōgana, a system where kanji were used to write sounds without regard to their meaning. There was more than one kanji that could be used equivalently for each syllable (at the time, a syllable was a mora). Over time the man'yōgana was reduced to a cursive form, the hiragana. Many hentaigana derive from different kanji from the ones for the now-standard hiragana, but some are the result of different styles of cursive writing. As hentaigana have derived from man'yōgana, there are hundreds of different hentaigana used to represent only 90 morae of the Japanese language.

On the other hand, katakana do not have hentaigana. Katakana's choices of man'yōgana segments had stabilized early on and established – with few exceptions – an unambiguous phonemic orthography (one symbol per sound) long before the 1900 script regularization.[3]

Hentaigana are not included in Unicode, though there is a proposal to encode them.[4][5][6]

Development of the hiragana syllabic n

The hiragana syllabic n (ん) derives from a cursive form of the character 无, and originally signified /mu͍/, the same as む. The spelling reform of 1900 separated the two uses, declaring that む could only be used for /mu͍/ and ん could only be used for syllable-final /ɴ/. Previously, in the absence of a character for the syllable-final /ɴ/, the sound was spelled (but not pronounced) identically to /mu͍/, and readers had to rely on context to determine what was intended. This ambiguity has led to some modern expressions based on what are, in effect, spelling pronunciations. For example, iwan to suru "trying to say" is ultimately a reading of mu as n.[citation needed] (The modern Japanese form 言おう iō comes from earlier 言はむ ihamu. Many other changes are seen here as well.)

Modern usage

Hentaigana are considered obsolete, but a few marginal uses remain. For example, the word otemoto is written in hentaigana on some chopsticks, many soba shops use hentaigana to spell kisoba on their signs. (See also: "Ye Olde" for "the old" on English signs.)

Hentaigana are used in some formal handwritten documents, particularly in certificates issued by classical Japanese cultural groups (e.g., martial art schools, etiquette schools, religious study groups, etc.). Also, they are occasionally used in reproductions of classic Japanese texts, akin to the use of blackletter in English and other Germanic languages to give an archaic flair. Modern poems may be composed and printed in hentaigana for visual effect.[7]

However, most Japanese people are unable to read hentaigana nowadays, only recognizing a few from their common use in shop signs, or figuring them out from context.

Incomplete list

Some of the following hentaigana are cursive forms of the same kanji as their standard hiragana counterparts, but simplified differently. Others descend from unrelated kanji that represent the same sound.

-

以(い)i

-

江(え)e

-

於(お)o

-

可(か)ka, ga

-

起(き)ki, gi

-

古(こ)ko, go

-

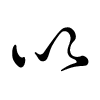

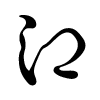

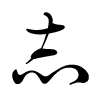

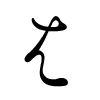

志(し)shi, ji

-

春(す)su, zu

-

多(た)ta, da

-

奈(な)na

-

能(の)no

-

者(は)ha, ba

-

由(ゆ)yu

-

連(れ)re

-

路(ろ)ro

-

王(わ)wa

Sources of hentaigana

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (October 2016) |

Hentaigana are adapted from the reduced and cursive forms of the following man’yōgana (kanji) characters.[8] Source characters for the kana are not repeated below for hentaigana even when there are alternative glyphs; some uncertain.

| a | i | u | e | o | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hira | Kata | Hentai | Hira | Kata | Hentai | Hira | Kata | Hentai | Hira | Kata | Hentai | Hira | Kata | Hentai | |

| 安 | 阿 | 悪亜愛 | 以 | 伊 | 意移異夷 | 宇 | 有雲憂羽于 | 衣 | 江 | 要盈得縁延 | 於 | ||||

| K | 加 | 閑可我駕賀歌哥香家嘉歟謌佳 | 機幾 | 支起貴喜祈季木 | 久 | 倶具求九供 | 計 | 介 | 遣氣希个 | 己 | 許故古期興子 | ||||

| S | 左 | 散 | 佐斜沙差乍狭 | 之 | 志四新事斯師 | 寸 | 須 | 春數壽爪 | 世 | 勢聲瀬 | 曽(曾) | 所楚處蘇 | |||

| T | 太 | 多 | 當堂田佗 | 知 | 千 | 地遲治致智池馳 | 川 | 川州 | 徒都津頭 | 天 | 停亭轉弖帝傳偏氐低 | 止 | 東登度等斗刀戸土 | ||

| N | 奈 | 那難名南菜 | 仁 | 爾耳二児丹尼而 | 奴 | 怒努駑 | 祢(禰) | 年子熱念音根寢 | 乃 | 能濃農廼野 | |||||

| H | 波 | 八 | 者盤半葉頗婆芳羽破 | 比 | 日飛悲非火避備妣 | 不 | 婦布風 | 部 | 旁倍遍弊邊閉敝幣反變辨經 | 保 | 寶本報奉穂 | ||||

| M | 末 | 万満萬眞馬間麻摩漫 | 美 | 三 | 見微身民 | 武 | 牟 | 無(无)舞務夢 | 女 | 免面馬目妻 | 毛 | 母裳茂蒙藻 | |||

| Y | 也 | 夜耶屋哉 | - | 由 | 遊游 | - | 與(与) | 與 | 代餘余世夜 | ||||||

| R | 良 | 羅蘭落等 | 利 | 梨里離理季 | 留 | 流 | 累類 | 礼(禮) | 連麗 | 呂 | 婁樓路露侶廬魯論 | ||||

| W | 和 | 王輪倭〇 | 為 | 井 | 居委遺 | - | 惠 | 衛彗 | 遠 | 乎 | 越尾緒 | ||||

See also

Notes

- ^ The hentai (変体: "variant" or "irregular form") in this word is not the same as the hentai (変態) which means "abnormal" or "pervert".

- ^ The reform was decreed in the 1900 revision of the Regulations on the Enforcement of the Elementary School Ordinance (小学校令施行規則, Shōgakkō-rei Shikōkisoku) for primary school education.[2]

References

- ^ 笹原宏之, 横山詔, Eric Long (2003). 現代日本の異体字. 三省堂. pp. 35–36. ISBN 4-385-36112-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frellesvig, Bjarke (2010-07-29). A History of the Japanese Language. Cambridge University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-139-48880-8.

- ^ Tranter, Nicolas (2012). The Languages of Japan and Korea. Routledge. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-415-46287-7.

- ^ Ruigrok van der Werven, Jeroen (February 15, 2009). "ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Proposal Summary Form to Accompany Submissions for Additions to the Repertoire of ISO/IEC 106461: A proposal for encoding the hentaigana characters" (PDF). JTC1/SC2/WG2 - ISO/IEC. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Ruigrok van der Werven, Jeroen (February 15, 2009). "ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Proposal Summary Form to Accompany Submissions for Additions to the Repertoire of ISO/IEC 106461: A proposal for encoding the hentaigana characters" (PDF). Jeroen Ruigrok van der Werven. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- ^ Japan N.B. / Tetsuji Orita (July 22, 2015). "Request for Comments on HENTAIGANA proposal (ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4670)" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ The Japan Interpreter. Center for Japanese Social and Political Studies. 1976. p. 395.

- ^ 伊地知, 鉄男 (1966). 仮名変体集. 新典社.

External links

- Chart of hentaigana calligraphy from O'Neill's A Reader of Handwritten Japanese

- A chart of hentaigana hosted by Jim Breen of the WWWJDIC

- Chart of kana from Engelbert Kaempfer circa 1693

- Hentaigana on signs Template:Ja icon

- L2/15-239 Proposal for Japanese HENTAIGANA - Unicode