History of London

London has a history that goes back 2,000 years. During this time, it has experienced plague, devastating fire, civil war, aerial bombardment, and terrorist attacks, yet, it has still grown to become one of the financial and cultural capitals of the world.

See City of London for details on the historic core of London.

Legendary foundations and prehistoric London

The Mediæval mythology of Geoffrey of Monmouth tells that London was founded by Brutus the Trojan in the Bronze Age, and was known as Troia Nova, or New Troy, which was corrupted to Trinovantum. (The Trinovantes were the tribe who inhabited the area prior to the Romans). King Lud renamed the town CaerLudein, from which London is derived. Geoffrey provides prehistoric London with a rich array of legendary kings and interesting stories.

However, despite intensive excavations, archaeologists have found no evidence of a prehistoric or major settlement in the area. There have been scattered prehistoric finds, evidence of farming, burial and traces of habitation, but nothing more substantial. It is now considered unlikely that a pre-Roman city existed, but as much of the Roman city remains unexcavated, it is still possible that some settlement may yet be discovered.

So, during the prehistoric times, London was most likely a rural area with scattered settlement. Rich finds such as the Battersea Shield, found in the Thames near Chelsea, suggest the area was important; there may have been important settlements at Egham and Brentford, and there was a hillfort at Uppall, but no city in the area of the Roman London, the present day City of London.

Roman London

Londinium was established as a town by the Romans after the invasion of 43 AD led by the Emperor Claudius. Archaeological excavation (undertaken by the Department of Urban Archaeology of the Museum of London now called MOLAS) since the 1970s has also failed to unearth any convincing traces of major settlement before c.50 — so ideas about Londinium being a military foundation around the Fort that protected London Bridge are now largely discounted.

The name Londinium is thought to be pre-Roman in origin although there is no consensus on what it means. One suggestion is that it derived from a personal name meaning 'fierce'. However, recent research by Richard Coates has suggested that the name derives from pre-Celtic Old European — Plowonida — from 2 roots, "plew" and "nejd", meaning something like "the flowing river" or "the wide flowing river". Londinium therefore means "the settlement on the wide river". He suggests that the river was called the Thames up river where it was narrower, and Plowonida down river where it was too wide to ford. For a discussion on the legends of London and Plowonida see [1]. The story of the settlement being named after Lud is considered unlikely.

Archaeologists now believe that London was founded as a civilian settlement by 50 AD. A wooden drain by the side of the main roman road excavated at No 1 Poultry has been dated to 47 which is likely to be the foundation date.

Ten years later, Londinium was sacked by the Iceni lead by the British queen Boudicca. Excavation has revealed extensive evidence of destruction by fire at this date, and recently a military compound has been discovered in the City of London which may have been the headquarters of the Roman fight back against the British uprising.

The city recovered after perhaps 10 years, and reached its population height by about 120 AD, with a population of around 60,000. London became the capital of Roman Britain (Britannia) (previously the capital was the older, nearby town of Colchester). Thereafter began a slow decline; however, habitation and associated building work did not cease. By 375 London was a small wealthy community protected by completed defences. By 410 Roman occupation officially came to an end, with the citizens being ordered to look after their own defenses. By the middle of the 5th Century the Roman city was practically abandoned.

Saxon London

After being abandoned for perhaps 150 years, its strategic position on the Thames meant that by 600 Anglo-Saxons had revived settlement in the area. These Saxon settlements were not in the ancient walled City of London (which was named Lundenburh = "London Fort"), but an area named Lundenwic = "London settlement" one kilometer upstream on the Thames.

Recent excavations in the Covent Garden area have uncovered extensive Anglo-Saxon settlement dating back into the 7th Century. The Excavations show that the settlement covered about 60 hectares, stretching from the present-day National Gallery site in the east to Aldwych in the west. The name "Aldwych" (from Anglo-Saxon ealdwīc = "old settlement") shows that some time, in the late 9th or early 10th Century the focus of settlement shifted from the 'Old District' back to the City of London. This may have been due to administrative changes introduced by Alfred the Great after his defeat of Guthrum and the Danes, or a move to a site easier to defend against Viking attacks.

Alfred appointed his son-in-law Earl Aethelred of Mercia, who was the heir to the destroyed Kingdom of Mercia, as Governor of London and established two defended Boroughs to defend the bridge which was probably rebuilt at this time. London became known as Lundenburh, and the southern end of the Bridge was established as the Borough of Southwark or Suthringa Geworc (defensive work of the men of Surrey) as it was originally known.

Mediæval London

See City of London for details of city government in the Mediæval period.

The Norman invasion of Britain in 1066 is usually considered to be the beginning of the Mediæval period. Under William the Conqueror several forts were constructed in London, the Tower of London, Baynard's Castle and Montfichet's Castle to prevent rebellions, William the Conqueror also granted a charter in 1067 upholding previous Saxon rights, privileges and laws. Its growing self-government became firm with election rights granted by King John in 1199 and 1215.

In 1097 William Rufus the son of William the Conqueror began the construction of 'Westminster Hall', the hall was to prove the basis of the Palace of Westminster which throughout the Mediæval period became the prime royal residence.

In 1176 construction began of the famous London Bridge (completed in 1209) which was built on the site of several earlier wooden bridges. This bridge would last for 600 years, and remained the only bridge across the River Thames until 1739.

During the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 led by Wat Tyler, London was invaded. A group of peasants stormed the Tower of London and executed the Lord Chancellor, Archbishop Simon Sudbury, and the Lord Treasurer. The peasants looted the city and set fire to numerous buildings. Tyler was stabbed to death by the Lord Mayor William Walworth in a confrontation at Smithfield, thus ending the revolt.

During the medieval period London grew up in two different parts. The nearby up-river town of Westminster became the Royal capital and centre of government, whereas the City of London became the centre of commerce and trade. The area between them became entirely urbanised by 1600.

Trade and commerce grew steadily during the Middle Ages, and London grew rapidly as a result. In 1100 London's population was little more than 15,000. By 1300 it had grown to roughly 80,000. Trade in London was organised into various guilds, which effectively controlled the city, and elected the Lord Mayor of London.

Mediæval London was made up of narrow and twisting streets, and most of the buildings were made from combustible materials such as wood and straw, which made fire a constant threat. Sanitation in London was poor. London lost at least half of its population during the Black Death in the mid-14th century. Between 1348 and the Great Plague of 1666 there were sixteen outbreaks of plague in the city.

Tudor London (1485-1603)

Henry Tudor, who seized the English throne as Henry VII in 1485, and married Elizabeth of York, thus putting an end to the War of the Roses, was a resolute and efficient monarch who centralised political power on the crown. He commissioned the celebrated ‘’Henry VII's Chapel’’ at Westminster Abbey, and continued the royal practice of borrowing funds from the City of London for his wars against the French - and repaid the loans on the due date, which was something of an innovation. Generally however, he took little interest in enhancing London. Nonetheless, the comparative stability of the Tudor kingdom had long term effects on the city, which grew rapidly during the 16th century as the nobles found that power and wealth were now best won by competing for favour at court, rather by warring amongst themselves in the provinces as they had so often done in the past.

Nonetheless Tudor London was often tumultuous by modern standards. In 1497 the pretender Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger brother of the boy monarch Edward V, encamped on Blackheath with his followers. At first there was a panic among the citizens, but the king organised the defence of the city, the rebels dispersed, and Warbeck was soon captured and hanged at Tyburn.

The Reformation produced little bloodshed in London, with most of the higher classes co-operating to bring about a gradual shift to Protestantism. Before the Reformation, more than half of the area of London was occupied by monasteries, nunneries and other religious houses, and that about a third of the inhabitants were monks, nuns and friars. Thus Henry VIII’s “Dissolution of the Monasteries” had a profound effect on the city as nearly all of this property changed hands. The process started in the mid 1530s, and by 1538 most of the larger houses had been abolished.

Shortly before his death, Henry refounded St Bartholomew's Hospital, but most of the large buildings were left unoccupied when he died in 1547. In the reign of Edward VI many passed to the City Livery Companies in lieu of payment of crown debts, and in some cases the rents arising from them were applied to charitable purposes. Separately, in 1550 the City purchased the manor of Southwark, on the south bank of the Thames and refounded the monastery of St Thomas as St Thomas's Hospital. Christ's Hospital was established in this period, and Bridewell Palace was converted into a children's home and house of correction for women. The Dissolution was also highly profitable for favoured courtiers who were able to obtain property on generous terms. Much of this was intensively rebuilt, cramming the extra housing required by London’s burgeoning population into every corner.

On the death of Edward VI in 1553, Lady Jane Grey was received at the Tower of London as queen, but the lord mayor, aldermen and recorder soon changed course and proclaimed Mary I of England queen instead. The following year the new monarch’s decision to marry Philip II of Spain provoked an uprising led by Sir Thomas Wyatt, who took possession of Southwark, and later reached Charing Cross, on the road from Westminster to the City, which is now regarded as the fulcrum of London, before moving on to Ludgate. But there was no uprising in the City and Wyatt surrendered. This demonstrates the crucial political importance of the City at that time, and the small importance of the districts outside the walls.

London was rapidly rising in importance amongst Europe’s commercial centres. Many small industries were booming, especially weaving. Trade expanded beyond Western Europe to Russia, the Levant and to the Americas. This was the period of mercantilism and monopoly trading companies such as the Russia Company (1555) and the East India Company (1600) were established in London by Royal Charter. The latter, which ultimately came to rule much of India, was one of the key institutions in London and in Britain as a whole for two and a half centuries. In 1572 the Spanish destroyed the great commercial city of Antwerp, giving London first place among the North Sea ports. Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well, for example Huguenots from France.

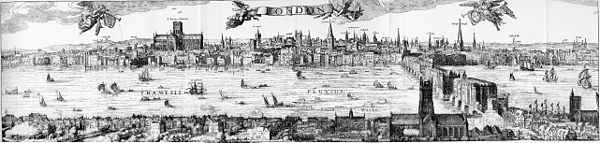

It was during this period that the first maps of London were drawn. The great bulk of the population was still enclosed in the City, living at a density which in the 21st century is unknown in the developed world. The old highway from the City to the royal court at Westminster, The Strand, was lined with aristocrats’ mansions, but the two settlements were otherwise separate, and Westminster was a small fraction of the size of the City. The Thames, not the Strand, was the most important means of communication between the two. Other districts which are almost as central in 21st century London as are Westminster and the City themselves were still rural in the late 16th century. Covent Garden really was a market garden. Hospitals and convalescent homes were established in Holborn and Bloomsbury to take advantage of the country air. Islington and Hoxton were outlying villages.

In 1561 lightning struck Old St Paul’s Cathedral. The roof was repaired, but the spire was never replaced. In 1565 Thomas Gresham founded a new mercantile exchange in the City, which was awarded the title the “Royal Exchange” by Queen Elizabeth in 1571.

The late 16th century, when William Shakespeare and his contemporaries lived and worked in London, was one of the most lustrous periods in the city’s cultural history. There was considerably hostility to the development of the theatre however. Public entertainments produced crowds, and crowds were feared by the authorities because they might become mobs, and by many ordinary citizens who dreaded that large gatherings might contribute to the spread of plague. Theatre itself was discountenanced by the increasingly influential Puritan strand in the nation. However Queen Elizabeth loved plays, which were performed for her privately at Court, and approved of public performances of " such plays only as were fitted to yield honest recreation and no example of evil." On April 11, 1582, the Lords of the Council wrote to the Lord Mayor to the effect that, as "her Majesty sometimes took delight in those pastimes, it had been thought not unfit, having regard to the season of the year and the clearance of the city from infection, to allow of certain companies of players in London, partly that they might thereby attain more dexterity and perfection the better to content her Majesty."

Nonetheless the theatres were mostly built outside of the City boundaries, especially on the south side of the river, which was already established as an entertainment centre where less salubrious entertainments such as bear-baiting might be seen. Theatres on Bankside included The Globe, The Rose, The Swan, and The Hope. The Theatre, and The Curtain were in located in Shoreditch, beyond the City’s eastern wall, and the Blackfriars Theatre, although within the walls, was outside of the City’s jurisdiction.

During the mostly calm later years of Elizabeth's some of her courtiers and some of the wealthier citizens of London built themselves country residences in Middlesex, Essex and Surrey. This was an early stirring of the villa movement, the taste for residences which were neither of the city nor on an agricultural estate, but when the last of the Tudors died in 1603, London was still very compact.

Stuart London (1603-1714)

London's expansion beyond the boundaries of the City was decisively established in the 17th century. In the opening years of that century the immediate environs of the City, with the principal exception of the aristocratic residences in the direction of Westminster, were still considered insalubrious. Immediately to the north was Moorfields, which had recently been drained and laid out in walks, but it was frequented by beggars and travellers who crossed it in order to get into London tried not to linger. Adjoining Moorfields were Finsbury Fields, a favourite practising ground for the archers. Mile End, then a common on the Great Eastern Road, was famous as a rendezvous for the troops.

The preparations for the coronation of King James I were interrupted by a severe epidemic of the plague, which may have killed over thirty thousand people. The Lord Mayor's Show, which had been discontinued for some years, was revived by order of the king in 1609. The dissolved monastery of the Charterhouse, which had been bought and sold by the courtiers several times, was purchased by Thomas Button for £13,000. The new hospital, chapel, and schoolhouse were begun in 1611. Charterhouse School was to be one of the principal public schools in London until it moved to Surrey in Victorian times, and the site is still used as a medical school.

The general meeting-place of Londoners in the day-time was the nave of Old St Paul's. Merchants conducted business in the aisles, and used the font as a counter upon which to make their payments; lawyers received clients at their particular pillars; and the unemployed looked for work. St Paul's Churchyard was the centre of the book trade and Fleet Street was a centre of public entertainment. Under James I the theatre, which established itself so firmly in the latter years of Elizabeth, grew further in popularity. The performances at the public theatres were complemented by elaborate masques at the royal court and at the inns of court.

Charles I acceded to the throne in 1625. During his reign aristocrats began to inhabit the West End in large numbers. In addition to those who had specific business at court, increasing numbers of country landowners and their families lived in London for part of the year simply for the social life. This was the beginning of the "London season". Lincoln's Inn Fields, was built about 1629. The piazza of Covent Garden, designed by England's first classically trained architect Inigo Jones followed in about 1632. The neighbouring streets were built shortly afterwards, and the names of Henrietta, Charles, James, King and York Streets were given after members of the royal family.

In January 1642 five members of parliament whom the King wished to arrest were granted refuge in the City. In August of the same year the King raised his banner at Nottingham, and during the English Civil War London took the side of the parliament. Initially the king had the upper hand in military terms and in November he won the Battle of Brentford a few miles to the west of London. The City organised a new makeshift army and Charles hesitated and retreated. Subsequently an extensive system of fortifications was built to protect London from a renewed attack by the Royalists. This comprised a strong earthen rampart, enhanced with bastions and redoubts. It was well beyond the City walls and encompassed the whole urban area, including Westminster and Southwark. London was not seriously threatened by the royalists again, and the financial resources of the City made an important contribution to the parliamentarians victory in the war.

The unsanitary and overcrowded City of London has suffered from the numerous outbreaks of the plague many times over the centuries, but in Britain it is the last major outbreak which is remembered as the "Great Plague" It occurred in 1665 and 1666 and killed around 60,000 people, which was one fifth of the population. Samuel Pepys chronicled the epidemic in his diary. On the 4th of September 1665 he wrote "I have stayed in the city till above 7400 died in one week, and of them about 6000 of the plague, and little noise heard day or night but tolling of bells."

The Great Plague was immediately followed by another catastrophe, albeit one which helped to put an end to the plague. On the Sunday 2nd of September 1666 the Great Fire of London broke out at one o'clock in the morning at a house in Pudding Lane in the southern part of the City. Fanned by an eastern wind the fire spread, and efforts to arrest it by pulling down houses to make firebreaks were disorganised to begin with. On Tuesday night the wind fell somewhat, and on Wednesday the fire slackened. On Thursday it was extinguished, but on the evening of that day the flames again burst forth at the Temple. Some houses were at once blown up by gunpowder, and thus the fire was finally mastered. The Monument was built to commemorate the fire: for over a century and a half it bore an inscription attributing the conflagration to a "popish frenzy".

The fire destroyed about sixty percent of the City, including Old St Paul's Cathedral, eighty-seven parish churches, forty-four livery company halls and the Royal Exchange. However the number of lives lost was surprisingly small; it is believed to have been sixteen at most. Within a few days of the fire three plans were presented to the king for the rebuilding of the city, by Christopher Wren, John Evelyn and Robert Hooke. Wren proposed to build main thoroughfares north and south, and east and west, to insulate all the churches in conspicuous positions, to form the most public places into large piazzas, to unite the halls of the twelve chief livery companies into one regular square annexed to the Guildhall, and to make a fine quay on the bank of the river from Blackfriars to the Tower of London. Wren wished to build the new streets straight and in three standard widths of thirty, sixty and ninety feet. Evelyn's plan differed from Wren's chiefly in proposing a street from the church of St Dunstan's in the East to the St Paul's, and in having no quay or terrace along the river. These plans were not implemented, and the rebuilt city generally followed the streetplan of the old one, and most of it has survived into the 21st century.

Nonetheless, the new City was different from the old one. Many aristocratic residents never returned, preferring to take new houses in the West End, where fashionable new districts such as St. James's were built close to the main royal residence, which was Whitehall Palace until it was destroyed by fire in the 1690s, and thereafter St. James's Palace. The rural lane of Piccadilly sprouted courtiers mansions such as Burlington House. Thus the separation between the middle class mercantile City of London, and the aristocratic world of the court in Westminster became complete. In the City itself there was a move from wooden buildings to stone and brick construction to reduce the risk of fire. The Act of Parliament "for rebuilding the city of London" stated "building with brick [is] not only more comely and durable, but also more safe against future perils of fire". From then on only doorcases, window-frames and shop fronts were allowed to be made of wood.

Christopher Wren's plan for a new model London came to nothing, but he was appointed to rebuild the ruined parish churches and to replace St Paul's Cathedral. His domed baroque cathedral was the primary symbol of London for at least a century and a half. As city surveyor, Robert Hooke oversaw the reconstruction of the City's houses. The East End, that is the area immediately to the east of the city walls, also became heavily populated in the decades after the Great Fire. London's docks began to extend downstream, attracting many working people who worked on the docks themselves and in the processing and distributive trades. These people lived in Whitechapel, Wapping, Stepney and Limehouse, generally in slum conditions.

In the winter of 1683-1684 a frost fair was held on the Thames. The frost, which began about seven weeks before Christmas and continued for six weeks after, was the greatest on record. The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, led to a large migration on Huguenots to London. They established a silk industry at Spitalfields.

At this time the City of London was becoming the world's leading financial centre, superseding Amsterdam in primacy. The Bank of England was founded in 1694, and the British East India Company was expanding its influence. Lloyd's of London also began to operate in the late 17th century. In 1700 London handled 80% of England's imports, 69% of its exports and 86% of its re-exports. Many of the goods were luxuries from the Americas and Asia such as silk, sugar, tea and tobacco. The last figure emphasises London's role as an entrepot: while it had many craftsmen in the 17th century, and would later acquire some large factories, its economic prominence was never based primarily on industry. Instead it was a great trading and redistribitution centre. Goods were brought to London by England's increasingly dominant merchant navy, not only to satisfy domestic demand, but also for re-export throughout Europe and beyond.

William III cared little for London, the smoke of which gave him asthma, and after the first fire at Whitehall Palace (1691) he purchased Nottingham House and transformed it into Kensington Palace. Kensington was then an insignificant village, but the arrival of the court soon caused it to grow in importance. The palace was rarely favoured by future monarchs, but its construction was another step in the expansion of the bounds of London. During the same reign Greenwich Hospital, then well outside the boundary of London, but now comfortably inside it, was begun; it was the naval complement to the Chelsea Hospital for former soldiers, which has been founded in 1681. During the reign of Queen Anne an act was passed authorising the building of fifty new churches to serve the greatly increased population living outside the boundaries of the City of London.

18th century London

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

The 18th century was a period of rapid growth for London, reflecting an increasing national population, the early stirrings of the Industrial Revolution, and London's role at the centre of the evolving British Empire.

During the Georgian period London spread beyond its traditional limits at an accelerating pace. New districts such as Mayfair were built for the rich in the West End, new bridges over the Thames encouraged an acceleration of development in South London and in the East End, the Port of London expanded downstream from the City.

A phenomenon of 18th century London was the Coffee house which became a popular place to debate ideas. Growing literacy and the development of the printing press meant that news became widely available. Fleet Street became the centre of the embryonic British press during the century.

18th century London was dogged by crime, the Bow Street Runners were established in 1750 as a professional police force. Penalties for crime were harsh, with the death penalty being applied for fairly minor crimes. Public hangings were a common in London, and were popular public events.

In 1780 London was rocked by the Gordon riots, an uprising by Protestants against Roman Catholic emancipation led by Lord George Gordon. Severe damage was caused to Catholic churches and homes, and 285 rioters were killed.

19th century London

During the 19th century London was transformed into the world's largest city and capital of the British Empire. Its population expanded from 1 million in 1800 to 6.7 million a century later. During this period, London became a global political, financial, and trading capital. In this position, it was largely unrivaled until the latter part of the century, when Paris and New York began to threaten its dominance.

While the city grew wealthy as Britain's holdings expanded, 19th century London was also a city of poverty, where millions lived in overcrowded and unsanitary slums. Life for the poor was immortalised by Charles Dickens in such novels as Oliver Twist.

In 1829 the prime minister Robert Peel established the Metropolitan Police Service as a police force covering the entire urban area. The force gained the nickname of "bobbies" or "peelers" named after Robert Peel.

19th century London was transformed by the coming of the railways. A new network of metropolitan railways allowed for the development of suburbs in neighboring counties from which middle-class and wealthy people could commute to the centre. While this spurred the massive outward growth of the city, the growth of greater London also exacerbated the class divide, as the wealthier classes emigrated to the suburbs, leaving the poor to inhabit the inner city areas.

The first railway to be built in London was a line from London Bridge to Greenwich, which opened in 1836. This was soon followed by the opening of great rail termini which linked London to every corner of Britain. These included Euston station (1837), Paddington station (1838), Fenchurch Street station (1841), Waterloo station (1848), King's Cross station (1850), and St Pancras station (1863). From the 1850s, the first lines of the London Underground were constructed.

The urbanised area continued to grow rapidly, spreading into Islington, Paddington, Belgravia, Holborn, Finsbury, Shoreditch, Southwark and Lambeth. Towards the middle of the century, London's antiquated local government system, consisting of ancient parishes and vestries, struggled to cope with the rapid growth in population. In 1855 the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW) was created to provide London with adequate infrastructure to cope with its growth.

One of its first tasks was addressing London's sanitation problems. At the time, raw sewage was pumped straight into the River Thames. This culminated in The Great Stink of 1858. The polluted drinking water (sourced from the Thames) also brought disease and epidemics to London's populace.

Parliament finally gave consent for the MBW to construct a massive system of sewers. The engineer put in charge of building the new system was Joseph Bazalgette. In what was one of the largest civil engineering projects of the 19th century, he oversaw construction of over 2100 km of tunnels and pipes under London to take away sewage and provide clean drinking water. When the London sewerage system was completed, the death toll in London dropped dramatically, and epidemics of cholera and other diseases were curtailed. Bazalgette's system is still in use today.

One of the most famous events of 19th-century London was the Great Exhibition of 1851. Held at The Crystal Palace, the fair attracted visitors from across the world and displayed Britain at the height of its Imperial dominance.

As the capital of a massive empire, London became a magnet for immigrants from the colonies and poorer parts of Europe. A large Irish population settled in the city during the Victorian period, with many of the newcomers refugees from the Irish potato famine. At one point, Irish immigrants made up about 20% of London's population. London also became home to a sizeable Jewish community, and small communities of Chinese and South Asians settled in the city.

In 1888, the new County of London was established, administered by the London County Council. This was the first elected London-wide administrative body, replacing the earlier Metropolitan Board of Works, which had been made up of appointees. The County of London covered what was then the full extent of the London conurbation, although the conurbation later outgrew the boundaries of the county.

Many famous buildings and landmarks of London were constructed during the 19th century including:

- Trafalgar Square

- Big Ben and the Houses of Parliament

- The Royal Albert Hall

- The Victoria and Albert Museum

- Tower Bridge

20th century London

London from 1900 to World War II

London entered the 20th century at the height of its influence as the capital of largest empire in history, but the new century was to bring many challenges.

London suffered its first bombing raids during World War I carried out by zeppelin airships; these killed around 700 people and caused great terror, but were merely a foretaste of what was to come.

The period between the two World Wars saw London's geographical extent growing more quickly than ever before or since. A preference for lower density suburban housing, typically semi-detached, by Londoners seeking a more "rural" lifestyle, superseded Londoners' old predilicition for terraced houses. This was facilitated not only by a continuing expansion of the rail network, including the Underground, but also by slowly widening car ownership.

Like the rest of the country, London suffered severe unemployment during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The population of London reached an all time peak of 8.6 million in 1939.

In the early part of the 20th century, Londoners used coal for heating their homes, which produced large amounts of smoke. In combination with climatic conditions this often caused a characteristic smog, and London became known for its typical "London Fog", also known as "Pea Soupers". London was sometimes referred to as "The Smoke" because of this. The Clean Air Act 1956 was introduced following the five-day "pea souper" of 5 December to 9 December 1952, which killed over 4,000 people, mandating the creating of "smokeless zones" where the use of "smokeless" fuels was required (this was at a time when most households still used open fires). The Act was effective.

London in World War II

During World War II, London, as many other British cities, suffered severe damage, being bombed extensively by the Luftwaffe as a part of The Blitz. Prior to the bombing, hundreds of thousands of children in London were evacuated to the countryside to avoid the bombing. Civilians took shelter from the air raids in underground stations.

London suffered severe damage during the bombing, the worst hit part being the Docklands area of the East End. By the war's end, nearly 35,000 Londoners had been killed, and around 50,000 seriously injured, tens of thousands of buildings were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of people were made homeless.

Postwar London

Immediately after the war, the 1948 Summer Olympics were held at Wembley Stadium, at a time when the city had barely recovered from the war.

In the immediate postwar years housing was a major issue in London, due to the large ammount of housing which had been destroyed in the war. The authorities decided upon high-rise blocks of flats as the answer to housing shortages. During the 1950 and 1960s the skyline of London altered dramatically as tower blocks were erected, although these later proved unpopular. In a bid to reduce the number of people living in overcrowded housing, a policy was introduced of encouraging people to move into newly built new towns surrounding London.

Starting in the mid 1960s, and partly as a result of the success of such UK musicians as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, London became an epicentre for the world-wide youth culture, exemplified by the Swinging London subculture which made Carnaby Street a household name of youth fashion around the world. London's role as a trendsetter for youth fashion was revived strongly in the 1980s during the New Wave and Punk eras. In the mid-1990s this was revived to some extent with the emergence of the Britpop era.

The outward expansion of London was slowed by the war, and the Green Belt established soon afterwards. Due to this outward expansion, in 1965 the old County of London (which by now only covered part of the London conurbation) and the London County Council were abolished, and the much larger area of Greater London was established with a new Greater London Council (GLC) to administer it, along with 32 new London boroughs.

In the early 1980s, due to political disputes between the GLC run by Ken Livingstone and the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher the GLC was abolished in 1986 and all of its powers were relegated to the London boroughs. This left London as the only large metropolis in the world without a central administration. In 2000, the Greater London Authority was established, covering the same area of Greater London as before and representing one of the nine regions of England, distinct from the rest of the South East. The London Commuter Belt covers an area much wider but is not normally considered part of London.

From the beginning of "The Troubles" in Northern Ireland in the early 1970s until the mid-1990s, London was subjected to repeated terrorist attacks by the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

Greater London's population declined steadily in the decades after World War II, from an estimated peak of 8.6 million in 1939 to around 6.8 million in the 1980s. However it then began to increase again in the late 1980s, encouraged by strong economic performance and an increasingly positive image. The London Plan, published by the Mayor of London in 2004, estimated that the population would reach 8.1 million by 2016, and continue to rise thereafter. This was reflected in a move towards denser, more urban styles of building, including an increased number of tall buildings, and proposals for major enhancements to the public transport network. However, funding for projects such as Crossrail remained a struggle.

21st Century London

At the turn of the 21st century, London hosted the much derided Millennium Dome at Greenwich, to mark the new century. Other Millennium projects were more successful. One was the largest observation wheel in the world, the "Millennium Wheel" of the London Eye, which was erected as a temporary structure, but soon became a fixture, and draws four million visitors a year. The National Lottery also released a flood of funds for major enhancements to existing attractions, for example the roofing of the Great Court at the British Museum.

On July 6, 2005 London won the bid to host the 2012 Olympics. However, celebrations were cut short the following day when, on July 7, 2005, London was rocked by a series of terrorist attacks. More than 50 were killed and 700 injured in the four bombings on London Underground and aboard a double decker bus near Russell Square.

Population

- 1AD - a few farmsteaders

- 50 - 5 - 10,000

- 140 - 45 - 60,000

- 300 - 10 - 20,000

- 400 - fewer than 5000?

- 500 a few hundred?

- 700 a few thousand in the new city of Lundenwic

- 900 a few thousand in the re-established city of Lundenburgh

- 1000 - 5 - 10,000

- 1100 - 10,000 - 20,000

- 1300 - 50 - 100,000 (according to research by Derek Keene)

- 1350 - 25 - 50,000 following the Black Death

- 1500 - 50,000 - 100,000

- 1600 - 100,000 - 200,000

- 1700 - 550,000 (nearly 10% of the population of England and Wales)

- 1750 - 700,000

- 1801 - 959,300 (at the time, the world's largest city)

- 1831 - 1,655,000

- 1851 - 2,363,000

- 1891 - 5,572,012

- 1901 - 6,506,954

- 1911 - 7,160,525

- 1921 - 7,386,848

- 1931 - 8,110,480

- 1939 - 8,615,245 (population peak)

- 1951 - 8,196,978

- 1961 - 7,992,616

- 1971 - 7,452,520

- 1981 - 6,805,000

- 1991 - 6,829,300

- 2001 - 7,322,400

- 2003 - 7,387,900

- 2016 - 8.2m (forecast in 'London's Place in the UK Economy' Corporation of London Sept. 2002)

The first Census was in 1801, so early dates are "guesstimates" based on archaeological density of sites compared with known population of the City of London between 1600 - 1800 (i.e., 50,000). Dates from 1300 onwards are based on what is probably better evidence, from historic records.

Figures for 1891 onwards are for Greater London in its 2001 limits (Greater London did not exist until 1965). Figures before 1971 have been reconstructed by the Office for National Statistics based on past censuses in order to fit the 2001 limits. Figures from 1981 onward are midyear estimates (revised as of 2004), which are more accurate than the censuses themselves, known to underestimate the population of London.

Historical places of note in London

- London Bridge

- Tower of London

- Houses of Parliament

- Buckingham Palace

- St. Paul's Cathedral

- Westminster Abbey

External links

- Motco.com map database - very detailed historical maps, commercial site

- Roman London - "In their own words" (PDF) A literary companion to the prehistory and archaeology of London by Kevin Flude

- London: The Biography First chapter of the book online by Peter Ackroyd