Brazil nut

| Brazil nut tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Lecythidaceae |

| Genus: | Bertholletia Bonpl. |

| Species: | B. excelsa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bertholletia excelsa Humb. & Bonpl.

| |

The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is a South American tree in the family Lecythidaceae, and it is also the name of the tree's commercially harvested edible seeds.[2] It is one of the largest and longest-lived trees in the Amazon rainforest. The fruit and its nutshell – containing the edible Brazil nut – are relatively large and weigh as much as 2 kg (4.4 lb) in total. As food, Brazil nuts are notable for diverse content of micronutrients, especially a high amount of selenium. The wood of the Brazil nut tree is prized for its quality in carpentry, flooring, and heavy construction.

Common names

[edit]In Portuguese-speaking countries, like Brazil, they are variously called "castanha-do-brasil"[3][4] (meaning "chestnut from Brazil" in Portuguese), "castanha-do-pará" (meaning "chestnut from Pará" in Portuguese), with other names: castanha-da-amazônia,[5] castanha-do-acre,[6] "noz amazônica" (meaning "Amazonian nut" in Portuguese), noz boliviana, tocari ("probably of Carib origin"[7]), and tururi (from Tupi turu'ri[8]) also used.[2]

In various Spanish-speaking countries of South America, Brazil nuts are called castañas de Brasil, nuez de Brasil, or castañas de Pará (or Para).[2][9]

In North America, as early as 1896, Brazil nuts were sometimes known by the slang term "nigger toes",[10][11][12] a vulgarity that fell out of use after the racial slur became more socially unacceptable.[13][14]

Description

[edit]

The Brazil nut is a large tree, reaching 50 metres (160 feet) tall,[15] and with a trunk 1 to 2 m (3 to 7 ft) in diameter, making it among the largest of trees in the Amazon rainforest. It may live for 500 years or more, and can often reach a thousand years of age.[16] The stem is straight and commonly without branches for well over half the tree's height, with a large, emergent crown of long branches above the surrounding canopy of other trees.

The bark is grayish and smooth. The leaves are dry-season deciduous, alternate, simple, entire or crenate, oblong, 20–35 centimetres (8–14 inches) long, and 10–15 cm (4–6 in) broad. The flowers are small, greenish-white, in panicles 5–10 cm (2–4 in) long; each flower has a two-parted, deciduous calyx, six unequal cream-colored petals, and numerous stamens united into a broad, hood-shaped mass.[citation needed]

Reproduction

[edit]Brazil nut trees produce fruit almost exclusively in pristine forests, as disturbed forests lack the large-bodied bees of the genera Bombus, Centris, Epicharis, Eulaema, and Xylocopa, which are the only ones capable of pollinating the tree's flowers, with different bee genera being the primary pollinators in different areas, and different times of year.[17][18][19] Brazil nuts have been harvested from plantations, but production is low and is currently not economically viable.[2][15][20]

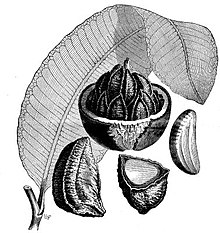

The fruit takes 14 months to mature after pollination of the flowers. The fruit itself is a large capsule 10–15 cm (4–6 in) in diameter, resembling a coconut endocarp in size and weighing up to 2 kg (4 lb 7 oz). It has a hard, woody shell 8–12 mm (3⁄8–1⁄2 in) thick, which contains eight to 24 wedge-shaped seeds 4–5 cm (1+5⁄8–2 in) long (the "Brazil nuts") packed like the segments of an orange, but not limited to one whorl of segments. Up to three whorls can be stacked onto each other, with the polar ends of the segments of the middle whorl nestling into the upper and lower whorls (see illustration above).

The capsule contains a small hole at one end, which enables large rodents like the agouti to gnaw it open.[21] They then eat some of the seeds inside while burying others for later use; some of these are able to germinate into new Brazil nut trees.[21] Most of the seeds are "planted" by the agoutis in caches during wet season,[21] and the young saplings may have to wait years, in a state of dormancy, for a tree to fall and sunlight to reach it, when it starts growing again. Capuchin monkeys have been reported to open Brazil nuts using a stone as an anvil.

Taxonomy

[edit]The Brazil nut family, the Lecythidaceae, is in the order Ericales, as are other well-known plants such as blueberries, cranberries, sapote, gutta-percha, tea, phlox, and persimmons. The tree is the only species in the monotypic genus Bertholletia,[2] named after French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet.[22]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The Brazil nut is native to the Guianas, Venezuela, Brazil, eastern Colombia, eastern Peru, and eastern Bolivia. It occurs as scattered trees in large forests on the banks of the Amazon River, Rio Negro, Tapajós, and the Orinoco. The fruit is heavy and rigid; when the fruits fall, they pose a serious threat to vehicles and potential for traumatic brain injury of people passing under the tree.[23]

Production

[edit]| Brazil nut production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (tonnes) |

| 33,118 | |

| 30,843 | |

| 5,697 | |

| World | 69,658 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[24] | |

In 2020, global production of Brazil nuts (in shells) was 69,658 tonnes, most of which derive from wild harvests in tropical forests, especially the Amazon regions of Brazil and Bolivia which produced 92% of the world total (table).

Environmental effects of harvesting

[edit]Since most of the production for international trade is harvested in the wild,[25][26] the business arrangement has been advanced as a model for generating income from a tropical forest without destroying it.[25] The nuts are most often gathered by migrant workers known as castañeros (in Spanish) or castanheiros (in Portuguese).[25] Logging is a significant threat to the sustainability of the Brazil nut-harvesting industry.[25][26]

Analysis of tree ages in areas that are harvested shows that moderate and intense gathering takes so many seeds that not enough are left to replace older trees as they die.[26] Sites with light gathering activities had many young trees, while sites with intense gathering practices had nearly none.[27]

European Union import regulation

[edit]In 2003, the European Union imposed strict regulations on the import of Brazilian-harvested Brazil nuts in their shells, as the shells are considered to contain unsafe levels of aflatoxins, a potential cause of liver cancer.[28]

Toxicity

[edit]Brazil nuts are susceptible to contamination by aflatoxins, produced by fungi, once they fall to the ground.[29] Aflatoxins can cause liver damage, including possible cancer, if consumed.[28] Aflatoxin levels have been found in Brazil nuts during inspections that were far higher than the limits set by the EU.[30] However, mechanical sorting and drying was found to eliminate 98% of aflatoxins; a 2003 EU ban on importation[28] was rescinded after new tolerance levels were set.

The nuts may contain traces of radium, a radioactive element, with a kilogram of nuts containing an activity between 40 and 260 becquerels (1 and 7 nanocuries). This level of radium is small, although higher than in other common foods. According to Oak Ridge Associated Universities, elevated levels of radium in the soil does not directly cause the concentration of radium, but "the very extensive root system of the tree" can concentrate naturally occurring radioactive material, when present in the soil.[31][unreliable source?] Radium can be concentrated in nuts only if it is present in the soil.[32]

Brazil nuts also contain barium, a metal with a chemical behavior quite similar to radium.[33] While barium, if ingested, can have toxic effects, such as weakness, vomiting, or diarrhea,[34] the amount present in Brazil nuts is orders of magnitude too small to have noticeable health effects.

Uses

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 2,743 kJ (656 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

12.27 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | 0.25 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 2.33 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 7.5 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

66.43 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Saturated | 15.137 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monounsaturated | 24.548 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polyunsaturated | 20.577 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

14.32 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tryptophan | 0.141 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 0.362 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 0.516 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 1.155 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 0.492 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 1.008 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 0.630 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 0.420 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 0.756 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 2.148 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.386 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 0.577 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 1.346 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 3.147 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 0.718 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 0.657 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 0.683 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 3.48 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Selenium | 1917 μg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Beta-sitosterol | 64 mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[35] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[36] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nutrition

[edit]Brazil nuts are 3% water, 14% protein, 12% carbohydrates, and 66% fats (table). The fat components are 16% saturated, 24% monounsaturated, and 24% polyunsaturated (see table for USDA source).

In a 100 grams (3.5 ounces) reference amount, Brazil nuts supply 659 calories, and are a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of dietary fiber (30% DV), thiamin (54% DV), vitamin E (38% DV), magnesium (106% DV), phosphorus (104% DV), manganese (57% DV), and zinc (43% DV). Calcium, iron, and potassium are present in moderate amounts (10-19% DV, table).

Selenium

[edit]Brazil nuts are a particularly rich source of selenium, with just 28 g (1 oz) supplying 544 micrograms of selenium or 10 times the DV of 55 micrograms (see table for USDA source).[37] However, the amount of selenium within batches of nuts may vary considerably.[38]

The high selenium content is used as a biomarker in studies of selenium intake and deficiency.[39][40] Consumption of just one Brazil nut per day over 8 weeks was sufficient to restore selenium blood levels and increase HDL cholesterol in obese women.[40]

Oil

[edit]

Brazil nut oil contains 48% unsaturated fatty acids composed mainly of oleic and linoleic acids, the phytosterol, beta-sitosterol,[41] and fat-soluble vitamin E.[42]

The following table presents the composition of fatty acids in Brazil nut oil (see USDA source in nutrition table):

| Palmitic acid | 10% |

| Palmitoleic acid | 0.2% |

| Stearic acid | 6% |

| Oleic acid | 24% |

| Linoleic acid | 24% |

| Alpha-linolenic acid | 0.04% |

| Saturated fats | 16% |

| Unsaturated fats | 48% |

Wood

[edit]The lumber from Brazil nut trees (not to be confused with Brazilwood) is of excellent quality, having diverse uses from flooring to heavy construction.[43] Logging the trees is prohibited by law in all three producing countries (Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru). Illegal extraction of timber and land clearances present continuing threats.[44] In Brazil, cutting down a Brazil nut tree requires previous authorization from the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources.[45][46]

Other uses

[edit]Brazil nut oil is used as a lubricant in clocks[47] and in the manufacturing of paint and cosmetics, such as soap and perfume.[43] Because of its hardness, the Brazil nutshell is often pulverized and used as an abrasive to polish materials, such as metals and ceramics, in the same way as jeweler's rouge, while charcoal from the shells can be used to purify water.[43]

See also

[edit]- Brazil nut cake

- List of culinary nuts

- Official list of endangered flora of Brazil

- Granular convection, also known as the "Brazil nut effect"

References

[edit]- ^ Americas Regional Workshop (Conservation & Sustainable Management of Trees, Costa Rica, November 1996) (1998). "Bertholletia excelsa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T32986A9741363. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32986A9741363.en. Retrieved December 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Mori, Scott A. "The Brazil Nut Industry – Past, Present, and Future". The New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Nomes comuns: castanha-do-brasil, castanha-do-pará ou castanha-da-amazônia" (PDF). - Folder Embrapa

- ^ COSTA, J. R. (et al.).Uma das espécies nativas mais valiosas da floresta amazônica de terra firme é a castanha-do-brasil ou castanha-da-amazônia (Bertholletia excelsa), - Acta Amazônica vol. 39(4) 2009: 843 - 850

- ^ Filho, João Carlos Meireles (2004). O livro de ouro da Amazônia: mitos e verdades sobre a região mais cobiçada do planeta (in Brazilian Portuguese). Ediouro. ISBN 978-85-00-01357-7. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Negócios para Amazônia sustentável" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 19, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2023. - Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Rio de Janeiro, 2003. p. 50.

- ^ Shepard, Glenn H.; Ramirez, Henri (March 2011). ""Made in Brazil": Human Dispersal of the Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa, Lecythidaceae) in Ancient Amazonia1". Economic Botany. 65 (1): 44–65. doi:10.1007/s12231-011-9151-6. S2CID 43465637.

- ^ Ferreira, A. B. H. (1986). Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa (2nd edition). Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira. p. 1729

- ^ PROYECTO PARA DECLARACIÓN DE ALÉRGENOS y SUSTANCIAS QUE PRODUCEN REACCIONES ADVERSAS EN LOS RÓTULOS DE LOS ALIMENTOS, CUALQUIERA SEA SU ORIGEN, ENVASADOS EN AUSENCIA DEL CLIENTE, LISTOS PARA SER OFRECIDOS AL CONSUMIDOR (DEC. 117/006 DEL RBN) [Project for Declaration of Allergens and Substances that produce adverse reactions in food labels, whatever their origin, packaged in the absence of the client, ready to be offered to the consumer] (PDF) (Report). Argentine government. n.d. p. 3.

- ^ Lyons, A. B. (2015). Plant Names, Scientific and Popular (2nd ed.). Arkose Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1345211849.

- ^ Young, W. J. (1911). "The Brazil Nut". Botanical Gazette. 52 (3): 226–231. doi:10.1086/330613.

- ^ ""Nigger", noun and adjective". Oxford English Dictionary. 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Essig, Laurie (July 12, 2016). "White Like Me, Nice Like Me". Psychology Today. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Brunvand, J. H. (1972). "The Study of Contemporary Folklore: Jokes". Fabula. 13 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1515/fabl.1972.13.1.1. S2CID 162318582.

- ^ a b Hennessey, Tim (March 2, 2001). "The Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa)". Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Taitson, Bruno (January 18, 2007). "Harvesting nuts, improving lives in Brazil". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on May 23, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Nelson, B. W.; Absy, M. L.; Barbosa, E. M.; Prance, G. T. (January 1985). "Observations on flower visitors to Bertholletia excelsa H. B. K. and Couratari tenuicarpa A. C. Sm. (Lecythidaceae)". Acta Amazonica. 15 (1): 225–234. doi:10.1590/1809-43921985155234. S2CID 87265447. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Moritz, A. (1984). Estudos biológicos da floração e da frutificação da castanha-do-Brasil (Bertholletia excelsa HBK) [Biological studies of flowering and fruiting of Brazil nuts (Bertholleira excelsa HKB)] (in Portuguese). Vol. 29. Archived from the original on August 17, 2009. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ Cavalcante, M. C.; Oliveira, F. F.; Maués, M. M.; Freitas, B. M. (October 27, 2017). "Pollination Requirements and the Foraging Behavior of Potential Pollinators of Cultivated Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa Bonpl.) Trees in Central Amazon Rainforest". Psyche: A Journal of Entomology. 2012: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2012/978019.

- ^ Ortiz, Enrique G. "The Brazil Nut Tree: More than just nuts". Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c Haugaasen, Joanne M. Tuck; Haugaasen, Torbjørn; Peres, Carlos A.; Gribel, Rogerio; Wegge, Per (March 30, 2010). "Seed dispersal of the Brazil nut tree (Bertholletia excelsa) by scatter-hoarding rodents in a central Amazonian forest". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 26 (3): 251–262. doi:10.1017/s0266467410000027. S2CID 84855812.

- ^ Burkhardt, Lotte (2022). Eine Enzyklopädie zu eponymischen Pflanzennamen [Encyclopedia of eponymic plant names] (pdf) (in German). Berlin: Botanic Garden and Botanical Museum, Freie Universität Berlin. doi:10.3372/epolist2022. ISBN 978-3-946292-41-8. S2CID 246307410. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Ideta MM, Oliveira LM, de Castro GL, Santos MA, Simões EL, Gonçalves DB, de Amorim RL (2021). "Traumatic brain injury caused by Brazil-nut fruit in the Amazon: A case series". Surgical Neurology International. 12: 399. doi:10.25259/SNI_279_2021. PMC 8422441. PMID 34513165.

- ^ "Brazil nut production in 2020; Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Evans, Kate (November 7, 2013). "Harvesting both timber and Brazil nuts in Peru's Amazon forests: Can they coexist?". Forests News. Center for International Forestry Research. Retrieved May 2, 2019 – via CIFOR.org.

- ^ a b c Kivner, Mark (May 11, 2010). "Intensive harvests 'threaten Brazil nut tree future'". BBC News: Science and Environment. Retrieved May 2, 2019.

- ^ Silvertown, J. (2004). "Sustainability in a nutshell". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 19 (6): 276–278. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.022. PMID 16701269.

- ^ a b c "Commission Decision of 4 July 2003 imposing special conditions on the import of Brazil nuts in shell originating in or consigned from Brazil". Official Journal of the European Union: 33–38. July 5, 2003. 2003/493/EC.

- ^ "Aflatoxins in food". European Food Safety Authority. March 1, 2007.

- ^ "Research improves the control of Brazil nut contamination by mycotoxins". AGÊNCIA FAPESP. August 2, 2017.

- ^ "Brazil Nuts". Oak Ridge Associated Universities. January 20, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ Adams, Rod (January 4, 2014). "BBC Bang Goes the Theory demonstrates that NOT all Brazil nuts are radioactive". Atomic Insights. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ "Brazil Nuts". Museum of Radiation and Radioactivity. Retrieved October 6, 2021.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Biomonitoring Summary". www.cdc.gov. September 3, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on May 9, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Selenium". Office of Dietary Supplements, US National Institutes of Health. March 26, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Chang, Jacqueline C.; Gutenmann, Walter H.; Reid, Charlotte M.; Lisk, Donald J. (1995). "Selenium content of Brazil nuts from two geographic locations in Brazil". Chemosphere. 30 (4): 801–802. Bibcode:1995Chmsp..30..801C. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(94)00409-N. PMID 7889353.

- ^ Garcia-Aloy, Mar; Hulshof, Paul J. M.; Estruel-Amades, Sheila; Osté, Maryse C. J.; Lankinen, Maria; Geleijnse, Johanna M.; de Goede, Janette; Ulaszewska, Marynka; Mattivi, Fulvio; Bakker, Stephan J. L.; Schwab, Ursula; Andres-Lacueva, Cristina (March 19, 2019). "Biomarkers of food intake for nuts and vegetable oils: an extensive literature search". Genes and Nutrition. 14 (1): 7. doi:10.1186/s12263-019-0628-8. PMC 6423890. PMID 30923582.

- ^ a b Souza, R. G. M.; Gomes, A. C.; Naves, M. M. V.; Mota, J. F. (April 16, 2015). "Nuts and legume seeds for cardiovascular risk reduction: scientific evidence and mechanisms of action". Nutrition Reviews. 73 (6): 335–347. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuu008. PMID 26011909.

- ^ Kornsteiner-Krenn, Margit; Wagner, Karl-Heinz; Elmadfa, Ibrahim (2013). "Phytosterol content and fatty acid pattern of ten different nut types". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. 83 (5): 263–270. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000168. PMID 25305221.

- ^ Ryan, E.; Galvin, K.; O'Connor, T. P.; Maguire, A. R.; O'Brien, N. M. (2006). "Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of brazil, pecan, pine, pistachio and cashew nuts". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 57 (3–4): 219–228. doi:10.1080/09637480600768077. PMID 17127473. S2CID 22030871.

- ^ a b c "Bertholletia excelsa - Bonpl". Plants for a Future. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ "Greenpeace Activists Trapped by Loggers in Amazon". Greenpeace. October 18, 2007. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Moncrieff, Virginia M. (September 21, 2015). "A little logging may go a long way". Forest News. Center for International Forestry Research. Retrieved July 8, 2020 – via CIFOR.org.

- ^ de Oliveira Wadt, Lucia Helena; de Souza, Joana Maria Leite. "Árvore do Conhecimento – Castanha-do-Brasil" [Tree of Knowledge – Brazil nut]. Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Lim, T. K. (2012). Edible Medicinal And Non Medicinal Plants: Volume 3, Fruits. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-007-2534-8.

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Lecythidaceae

- Trees of the Amazon rainforest

- Edible nuts and seeds

- Fruit trees

- Trees of Brazil

- Trees of Bolivia

- Trees of Colombia

- Trees of Guyana

- Trees of Peru

- Trees of Venezuela

- Tropical agriculture

- Crops originating from South America

- Crops originating from Brazil

- Crops originating from Bolivia

- Crops originating from Peru

- Crops originating from Colombia

- Flora of the Amazon

- Vulnerable flora of South America

- Taxa named by Aimé Bonpland

- Taxa named by Alexander von Humboldt