Occupy Wall Street

| Occupy Wall Street | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Occupy movement | |

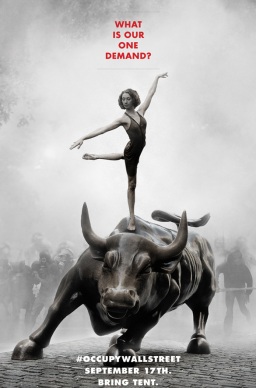

Adbusters poster advertising the original protest | |

| Date | September 17, 2011 |

| Location | New York City 40°42′33.79″N 74°0′40.76″W / 40.7093861°N 74.0113222°W |

| Caused by | Wealth inequality, political corruption,[1] corporate influence of government, inter alia. |

| Methods | |

| Number | |

Zuccotti Park Other activity in NYC:

| |

Occupy Wall Street (OWS) is the name given to a protest movement that began on September 17, 2011, in Zuccotti Park, located in New York City's Wall Street financial district, receiving global attention and spawning the Occupy movement against social and economic inequality worldwide.[7]

The Canadian, anti-consumerist, pro-environment group/magazine Adbusters initiated the call for a protest.

The main issues raised by Occupy Wall Street were social and economic inequality, greed, corruption and the perceived undue influence of corporations on government—particularly from the financial services sector. The OWS slogan, "We are the 99%", refers to income inequality and wealth distribution in the U.S. between the wealthiest 1% and the rest of the population. To achieve their goals, protesters acted on consensus-based decisions made in general assemblies which emphasized direct action over petitioning authorities for redress.[8][nb 1]

The protesters were forced out of Zuccotti Park on November 15, 2011. After several unsuccessful attempts to re-occupy the original location, protesters turned their focus to occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes, and college and university campuses.

On December 29, 2012, Naomi Wolf of The Guardian newspaper provided U.S. government documents which revealed that the FBI and DHS had monitored Occupy Wall Street through its Joint Terrorism Task Force, despite labeling it a peaceful movement.[9] The New York Times reported in May 2014 that declassified documents showed extensive surveillance and infiltration of OWS-related groups across the country.[10]

Origins

The original protest was initiated by Kalle Lasn and Micah White of Adbusters, a Canadian anti-consumerist publication, who conceived of a September 17 occupation in lower Manhattan. Lasn registered the OccupyWallStreet.org web address on June 9.[11] That same month, Adbusters emailed its subscribers saying “America needs its own Tahrir.” White said the reception of the idea "snowballed from there".[11][12] In a blog post on July 13, 2011,[13] Adbusters proposed a peaceful occupation of Wall Street to protest corporate influence on democracy, the lack of legal consequences for those who brought about the global crisis of monetary insolvency, and an increasing disparity in wealth.[12] The protest was promoted with an image featuring a dancer atop Wall Street's iconic Charging Bull statue.[14][15][16]

On August 1, 2011, almost a month prior to the major media event, a group of artists were arrested after a series of days protesting nude as an art performance on Wall Street.[17] This event may have inspired or triggered the major event to follow. This was a protest by the 49 participants on American Institutions and was titled "Ocularpation: Wall Street" by artist Zefrey Throwell.[18]

Then in an unrelated incident, a group called New Yorkers Against Budget Cuts (NYAB) was formed, which promoted a "sleep in" in lower Manhattan called "Bloombergville," in July 2011, preceding OWS, and provided a number of activists to begin organizing.[19][20] Activist, anarchist and anthropologist David Graeber and several of his associates attended the NYAB general assembly but, disappointed that the event was intended to be a precursor to marching on Wall Street with predetermined demands, Graeber and his small group created their own general assembly, which eventually developed into the New York General Assembly. The group began holding weekly meetings to work out issues and the movement's direction, such as whether or not to have a set of demands, forming working groups and whether or not to have leaders.[11][21][22][nb 2] The Internet group Anonymous created a video encouraging its supporters to take part in the protests.[23] The U.S. Day of Rage, a group that organized to protest "corporate influence [that] corrupts our political parties, our elections, and the institutions of government," also joined the movement.[24][25] The protest itself began on September 17; a Facebook page for the demonstrations began two days later on September 19 featuring a YouTube video of earlier events. By mid-October, Facebook listed 125 Occupy-related pages.[26]

The original location for the protest was One Chase Manhattan Plaza, with Bowling Green Park (the site of the "Charging Bull") and Zuccotti Park as alternate choices. Police discovered this before the protest began and fenced off two locations; but they left Zuccotti Park, the group's third choice, open. Since the park was private property, police could not legally force protesters to leave without being requested to do so by the property owner.[27][28] At a press conference held the same day the protests began, New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg explained, "people have a right to protest, and if they want to protest, we'll be happy to make sure they have locations to do it."[25]

Because of its connection to the financial system, lower Manhattan has seen many riots and protests since the 1800s,[29] and OWS has been compared to other historical protests in the United States.[30] Commentators have put OWS within the political tradition of other movements that made themselves known by occupation of public spaces, such as Coxey's Army in 1894, the Bonus Marchers in 1932, and the May Day protesters in 1971.[31][32]

More recent prototypes for OWS include the British student protests of 2010, 2009-2010 Iranian election protests, the Arab Spring protests,[33] and, more closely related, protests in Greece and Spain. These antecedents have in common with OWS a reliance on social media and electronic messaging,[34][35] as well as the belief that financial institutions, corporations, and the political elite have been malfeasant in their behavior toward youth and the middle class.[36][37] Occupy Wall Street, in turn, gave rise to the Occupy movement in the United States.[38][39][40] David Graeber has argued that the Occupy movement, in its anti-hierarchical and anti-authoritarian consensus-based politics, its refusal to accept the legitimacy of the existing legal and political order, and its embrace of prefigurative politics, has roots in an anarchist political tradition.[41] Sociologist Dana Williams has likewise argued that "the most immediate inspiration for Occupy is anarchism," and the LA Times has identified the "controversial, anarchist-inspired organizational style" as one of the hallmarks of OWS.[42][43]

Overview

"We are the 99%"

The Occupy protesters' slogan "We are the 99%" refers to the protester's perceptions of, and attitudes regarding, income disparity in the US and economic inequality in general, which have been main issues for OWS. It derives from a "We the 99%" flyer calling for OWS's second General Assembly in August 2011. The variation "We are the 99%" originated from a tumblr page of the same name.[44][45] Huffington Post reporter Paul Taylor said the slogan is "arguably the most successful slogan since Hell no, we won't go!" of the Vietnam War era, and that the majority of Democrats, independents and Republicans see the income gap as causing social friction.[44] The slogan was boosted by statistics which were confirmed by a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report released in October 2011.[46]

Income inequality

Income inequality is a focal point of the Occupy Wall Street protests.[52][53][54] This focus by the movement was studied by Arindajit Dube and Ethan Kaplan of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who noted that "inequality in the U.S. has risen dramatically over the past 40 years. So it is not too surprising to witness the rise of a social movement focused on redistribution...Greater inequality may reflect as well as exacerbate factors that make it relatively more difficult for lower-income individuals to mobilize on behalf of their interests...Yet, even the economic crisis of 2007 did not initially produce a left social movement...Only after it became increasingly clear that the political process was unable to enact serious reforms to address the causes or consequences of the economic crisis did we see the emergence of the OWS movement...Overall, a focus on the 1 percent concentrates attention on the aspect of inequality most clearly tied to the distribution of income between labor and capital...We think OWS has already begun to influence the public policy making process."[55][citation needed] An article on the same subject published in Salon Magazine by Natasha Leonard noted "Occupy has been central to driving media stories about income inequality in America. Late last week, Radio Dispatch’s John Knefel compiled a report for media watchdog Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR), which illustrates Occupy’s success: Media focus on the movement in the past half year, according to the report, has been almost directly proportional to the attention paid to income inequality and corporate greed by mainstream outlets. During peak media coverage of the movement last October, mentions of the term “income inequality” increased “fourfold”...tokens of Occupy rhetoric — most notably the idea of a “99 percent” against a “1 percent” — has seeped into everyday cultural parlance."[56] As income inequality remained on people's minds, Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney said such a focus was about envy and class warfare.[57]

Goals

OWS's goals include a reduction in the influence of corporations on politics,[59] more balanced distribution of income,[59] more and better jobs,[59] bank reform[40] (especially to curtail speculative trading by banks), forgiveness of student loan debt[59][60] or other relief for indebted students,[61][62] and alleviation of the foreclosure situation.[63] Some media label the protests "anti-capitalist",[64] while others dispute the relevance of this label.[65] Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times noted "while alarmists seem to think that the movement is a 'mob' trying to overthrow capitalism, one can make a case that, on the contrary, it highlights the need to restore basic capitalist principles like accountability".[66] Rolling Stone writer Matt Taibbi asserted, "These people aren't protesting money. They're not protesting banking. They're protesting corruption on Wall Street."[67] In contradiction to such views, academic Slavoj Zizek wrote, "capitalism is now clearly re-emerging as the name of the problem,"[68] and Forbes columnist Heather Struck wrote, "In downtown New York, where protests fomented, capitalism is held accountable for the dire conditions that a majority of Americans face amid high unemployment and a credit collapse that has ruined the housing market and tightened lending among banks."[69]

Some protestors have favored a fairly concrete set of national policy proposals.[70][71] One OWS group that favored specific demands created a document entitled the 99 Percent Declaration,[72] but this was regarded as an attempt to "co-opt" the "Occupy" name,[73] and the document and group were rejected by the General Assemblies of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy Philadelphia.[73] However others, such as those who issued the Liberty Square Blueprint, are opposed to setting demands, saying they would limit the movement by implying conditions and limiting the duration of the movement.[74] David Graeber, an OWS participant, has also criticized the idea that the movement must have clearly defined demands, arguing that it would be a counterproductive legitimization of the very power structures the movement seeks to challenge.[75] In a similar vein, scholar and activist Judith Butler has challenged the assertion that OWS should make concrete demands: "So what are the demands that all these people are making? Either they say there are no demands and that leaves your critics confused. Or they say that demands for social equality, that demands for economic justice are impossible demands and impossible demands are just not practical. But we disagree. If hope is an impossible demand then we demand the impossible."[76] Regardless, activists favor a new system that fulfills what is perceived as the original promise of democracy to bring power to all the people.[77]

Protester demographics

Early on the protesters were mostly young.[78][79] As the protest grew, older protesters also became involved.[80] The average age of the protesters was 33, with people in their 20s balanced by people in their 40s.[81] Various religious faiths have been represented at the protest including Muslims, Jews, and Christians.[82] Rabbi Chaim Gruber,[83] however, is reportedly the only clergy member to have actually camped at Zuccotti Park.[84][85][86] The Associated Press reported in October that there was "diversity of age, gender and race" at the protest.[80] A study based on survey responses at OccupyWallSt.org reported that the protesters were 81.2% White, 6.8% Hispanic, 2.8% Asian, 1.6% Black, and 7.6% identifying as "other".[87][88]

According to a survey of occupywallst.org website visitors[89] by the Baruch College School of Public Affairs published on October 19, of 1,619 web respondents, one-third were older than 35, half were employed full-time, 13% were unemployed and 13% earned over $75,000. When given the option of identifying themselves as Democrat, Republican or Independent/Other 27.3% of the respondents called themselves Democrats, 2.4% called themselves Republicans, while the rest, 70%, called themselves independents.[90] A study released by City University of New York found that over a third of protestors had incomes over $100,000, 76 percent had bachelor's degrees, and 39 percent had graduate degrees. While a large percent of them were employed, they largely reported they were "unconstrained by highly demanding family or work commitments". The study also found that they disproportionally represented upper-class, highly educated white males.[91][92] A survey of 301 respondents by a Fordham University political science professor identified the protester's political affiliations as 25% Democrat, 2% Republican, 11% Socialist, 11% Green Party, 0% Tea Party, and 12% "Other"; meanwhile, 39% of the respondents said they did not identify with any political party.[93] Ideologically the Fordham survey found 80% self-identifying as slightly to extremely liberal, 15% as moderate, and 6% as slightly to extremely conservative.[93]

Main organization

The assembly is the main OWS decision-making body and uses a modified consensus process, where participants attempt to reach consensus and then drop to a 9/10 vote if consensus is not reached. Consensus is a process of common sentiment. It is not agreement. Participants are given room for dissent and complex ideas are able to form. The process has been used in many indigenous traditions, Quaker practices, the women's liberation movement, anti-nuclear movement, and alter-globalization movement. In the assembly OWS working groups and affinity groups discuss their thoughts and needs, and the meetings are open to the public for both attendance and speaking.[94] The meetings are without formal leadership. Meeting participants comment upon committee proposals using a process called a "stack", which is a queue of speakers that anyone can join. New York uses what is called a progressive stack, in which people from marginalized groups are sometimes allowed to speak before people from dominant groups. Facilitators and "stack-keepers" urge speakers to "step forward, or step back" based on which group they belong to, meaning that women and minorities may move to the front of the line, while white men must often wait for a turn to speak.[95][96] Participants take minutes of the meetings so that other participants, who are not in attendance, can be kept up-to-date.[97][98] In addition to the over 70 working groups[99] that perform much of the daily work and planning of Occupy Wall Street, the organizational structure also includes "spokes councils," at which every working group can participate.[100]

Even with the perception of a movement with no leaders, leaders have emerged. A facilitator of some of the movement's more contentious discussions, Nicole Carty, says “Usually when we think of leadership, we think of authority, but nobody has authority here,” – “People lead by example, stepping up when they need to and stepping back when they need to.”[101] According to Fordham University communications professor Paul Levinson, Occupy Wall Street and similar movements symbolize another rise of direct democracy that has not actually been seen since ancient times.[102][103]

Funding

During the initial weeks of the park encampment it was reported that most of OWS funding was coming from donors with incomes in the $50,000 to $100,000 range, and the median donation was $22.[81] According to finance group member Pete Dutro, OWS had accumulated over $700,000.[104] The largest single donor to the movement was former New York Mercantile Exchange vice chairman Robert Halper, who was noted by media as having also given the maximum allowable campaign contribution to Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney.[105] During the period that protesters were encamped in the park the funds were being used to purchase food and other necessities and to bail out fellow protesters. With the closure of the park to overnight camping on November 15, members of the OWS finance committee stated they would initiate a process to streamline the movement and re-evaluate their budget and eliminate or merge some of the "working groups" they no longer needed on a day-to-day basis.[106][107]

Met with increasing costs and significant overhead expenses in order to sustain the movement, an internal audit from the fiscal management team known as the "accounting working group" revealed on March 2, 2012, that only $44,000 of the several hundred thousand dollars raised still remained available. The report warned that if current revenues and expenses were maintained at current levels, then funds would run out in three weeks.[108][109] Some of the movement's biggest costs include ground-level activities such as food kitchens, street medics, bus tickets, subway passes, and printing expenses.[110][111] In late February 2012 it was reported that a group of business leaders including Ben Cohen, Jerry Greenfield, Danny Goldberg, Norman Lear, and Terri Gardner[112] created a new working group, the Movement Resource Group, and with it have pledged $300,000 with plans to add $1,500,000 more.[113][114] The money would be made available in the form of grants of up to $25,000 for eligible recipients.

The People's Library

The People’s Library at Occupy Wall Street was started a few days after the protest when a pile of books was left in a cardboard box at Zuccotti Park. The books were passed around and organized, and as time passed, it received additional books and resources from readers, private citizens, authors and corporations.[115] As of November 2011 the library had 5,554 books cataloged in LibraryThing and its collection was described as including some rare or unique articles of historical interest.[116] According to American Libraries, the library's collection had "thousands of circulating volumes," which included "holy books of every faith, books reflecting the entire political spectrum, and works for all ages on a huge range of topics."[115]

Following the example of the OWS People's Library, protestors throughout North America and Europe formed sister libraries at their encampments.[117]

Zuccotti Park encampment

Prior to being closed to overnight use and during the occupation of the space, somewhere between 100 and 200 people slept in Zuccotti Park. Initially tents were not allowed and protesters slept in sleeping bags or under blankets.[118] Meal service started at a total cost of about $1,000 per day. While some visitors ate at nearby restaurants, according to the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post many businesses surrounding the park were adversely affected.[119][120][121] Contribution boxes collected about $5,000 a day, and supplies came in from around the country.[119] Eric Smith, a local chef who was laid off at the Sheraton in Midtown, said that he was running a five-star restaurant in the park.[122] In late October kitchen volunteers complained about working 18-hour days to feed people who were not part of the movement and served only brown rice, simple sandwiches, and potato chips for three days.[123]

Many protesters used the bathrooms of nearby business establishments. Some supporters donated use of their bathrooms for showers and the sanitary needs of protesters.[124]

New York City requires a permit to use "amplified sound," including electric bullhorns. Since Occupy Wall Street did not have a permit, the protesters created the "human microphone" in which a speaker pauses while the nearby members of the audience repeat the phrase in unison. The effect has been called "comic or exhilarating—often all at once." Some feel this provided a further unifying effect for the crowd.[125][126]

During the weeks that overnight use of the park was allowed, a separate area was set aside for an information area which contained laptop computers and several wireless routers.[127][128] The items were powered with gas generators until the New York City Fire Department removed them on October 28, saying they were a fire hazard.[129] Protesters then used bicycles rigged with an electricity-generating apparatus to charge batteries to power the protesters' laptops and other electronics.[130][131] According to the Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database, the media team, while unofficial, ran websites like Occupytogether.org, video livestream, a "steady flow of updates on Twitter, and Tumblr" as well as Skype sessions with other demonstrators.[132]

On October 6, Brookfield Office Properties, which owns Zuccotti Park, issued a statement saying: "Sanitation is a growing concern... Normally the park is cleaned and inspected every weeknight [but] because the protesters refuse to cooperate ... the park has not been cleaned since Friday, September 16 and as a result, sanitary conditions have reached unacceptable levels."[133][134]

On October 13, New York City's mayor Bloomberg and Brookfield announced that the park must be vacated for cleaning the following morning at 7 am.[135] However, protesters vowed to "defend the occupation" after police said they wouldn’t allow them to return with sleeping bags and other gear following the cleaning, and many protesters spent the night sweeping and mopping the park.[136][137] The next morning the property owner postponed its cleaning effort.[136] Having prepared for a confrontation with the authorities to prevent the cleaning effort from proceeding, some protesters clashed with police in riot gear outside City Hall after it was canceled.[135] MTV followed two protesters for their series Real Life one of whom, Bryan, was on the sanitation crew. Filming took place during the time when the cleanup happened.[138]

On October 20, residents at a community board meeting complained about inadequate sanitation, verbal taunts and harassment by protesters, noise, and related issues. One resident angrily complained that the protesters "[a]re defecating on our doorsteps"; board member Tricia Joyce said, "They have to have some parameters. That doesn't mean the protests have to stop. I'm hoping we can strike a balance on parameters because this could be a long term stay."[139]

Shortly after midnight on November 15, 2011, the New York City Police Department gave protesters notice from the park's owner (Brookfield Office Properties) to leave Zuccotti Park due to its purportedly unsanitary and hazardous conditions. The notice stated that they could return without sleeping bags, tarps or tents.[140][141] About an hour later, police in riot gear began removing protesters from the park, arresting some 200 people in the process, including a number of journalists.

On December 31, 2011, protesters started to re-occupy the park. At one point, protesters started to push police barricades into the streets. Police quickly put the barricades back up. Occupiers then started to take down barricades from all sides of the park and stored them in a pile in the middle of Zuccotti Park.[142] Police called in re-enforcements as more activists entered the park. Police tried to enter the park but were pushed back by protesters. There were reports of pepper-spray being used by the police. About 12:40 am after the group celebrated New Years in the park, they exited the park and marched down Broadway. Police in riot gear started to clear out the park around 1:30 am. Sixty-eight people were arrested in connection with the event, including one accused of stabbing a police officer in the hand with a pair of scissors.[143]

Since the closure of the Zuccotti Park encampment, some former campers have been allowed to sleep in local churches, but how much longer they will be welcomed is in question and even former park occupiers debate whether or not they can continue to provide funds and meals for homeless protesters. Since the removal, New York protesters have been divided in their opinion as to the importance of the occupation of a space with some believing that actual encampment is unnecessary, and even a burden.[144] Since the closure of the Zuccotti Park encampment, the movement has turned its focus on occupying banks, corporate headquarters, board meetings, foreclosed homes, college and university campuses, and Wall Street itself. Since its inception, the Occupy Wall Street protests in New York City have cost the city an estimated $17 million in overtime fees to provide policing of protests and encampment inside Zuccotti Park.[145][146][147]

On March 17, 2012, Occupy Wall Street demonstrators attempted to mark the movement's six-month anniversary by reoccupying Zuccotti Park. Protestors were soon cleared away by police, who made over 70 arrests. Veteran protesters said the force used by police was the most violent they had witnessed and a Guardian reporter witnessed a protester being slammed into a glass door by a police officer.[148][149] On March 24, hundreds of OWS protesters marched from Zuccotti Park to Union Square in a demonstration against police violence.[150]

On September 17, 2012, protesters returned to Zuccotti Park to mark the one-year anniversary of the beginning of the occupation. Protesters blocked access to the New York Stock Exchange as well as other intersections in the area. This, along with several violations of Zuccotti Park rules, lead police to surround groups of protesters, at times pulling protesters from the crowds to be arrested for blocking pedestrian traffic. A police lieutenant instructed reporters not to take pictures. The New York Times reported that two officers shoved city councilman Jumaane D. Williams off a bench with batons after he refused two orders to move. A spokesman for Williams later stated that he had been pushed by police while trying to explain his reason for being in the park, but was not arrested or injured. There were 185 arrests across the city.[151][152][153][154]

Security, crime and legal issues

OWS demonstrators complained of thefts of assorted items such as cell phones and laptops; thieves also stole $2500 of donations that were stored in a makeshift kitchen.[155] In November, a man was arrested for breaking an EMT's leg.[156]

NYPD spokesman Paul Browne said protesters delayed reporting crime until three complaints were made against the same individual.[157] The protesters denied a "three strikes policy", and one protester told the New York Daily News that he had heard police respond to an unspecified complaint by saying, "You need to deal with that yourselves".[158]

After several weeks of occupation, protesters had made enough allegations of rape, sexual assault and gropings that women-only sleeping tents were set up.[159][160][161][162] Occupy Wall Street organizers released a statement regarding the sexual assaults stating, "As individuals and as a community, we have the responsibility and the opportunity to create an alternative to this culture of violence, We are working for an OWS and a world in which survivors are respected and supported unconditionally... We are redoubling our efforts to raise awareness about sexual violence. This includes taking preventative measures such as encouraging healthy relationship dynamics and consent practices that can help to limit harm.”[163]

It was revealed that an internal Department of Homeland Security report warned that Occupy Wall Street protests were a potential source of violence; the report stated that "mass gatherings associated with public protest movements can have disruptive effects on transportation, commercial, and government services, especially when staged in major metropolitan areas". The DHS keeps a file on the movement and monitors social media for information, according to leaked emails released by Wikileaks.[164][165]

Brooklyn Bridge arrests

On October 1, 2011, a large group of protesters set out to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge resulting in 700 arrests. Some said the police had tricked protesters, allowing them onto the bridge, and even escorting them partway across.[166][167] Jesse A. Myerson, a media coordinator for Occupy Wall Street said, “The cops watched and did nothing, indeed, seemed to guide us onto the roadway.”[168] However, some statements by protesters supported descriptions of the event given by police: for example, one protester tweeted that "The police didn't lead us on to the bridge. They were backing the fuck up."[169] A spokesman for the New York Police Department, Paul Browne, said that protesters were given multiple warnings to stay on the sidewalk and not block the street, and were arrested when they refused.[3] By October 2, all but 20 of the arrestees had been released with citations for disorderly conduct and a criminal court summons.[170] On October 4, a group of protesters who were arrested on the bridge filed a lawsuit against the city, alleging that officers had violated their constitutional rights by luring them into a trap and then arresting them; Mayor Bloomberg, commenting previously on the incident, had said that "[t]he police did exactly what they were supposed to do."[171]

In June 2012, a federal judge ruled that the protesters had not received sufficient warning that they would be arrested if they entered the roadway. While the police had argued that the protesters had received adequate warning, after reviewing video evidence, Judge Jed S. Rakoff sided with protesters saying, "a reasonable officer in the noisy environment defendants occupied would have known that a single bull horn could not reasonably communicate a message to 700 demonstrators".[172]

Court cases

In May 2012, three cases in a row were thrown out of court, the most recent one for "insufficient summons".[173] In another case, photographer Alexander Arbuckle was charged with blocking traffic for standing in the middle of the street, according to NYPD Officer Elisheba Vera. However, according to Village Voice staff writer Nick Pinto, this account was not corroborated by photographic and video evidence taken by protesters and the NYPD.[174] In yet another case, Sgt. Michael Soldo, the arresting officer, said Jessica Hall was blocking traffic. But under cross-examination Soldo admitted, it was actually the NYPD metal barricades which blocked traffic. This was also corroborated by the NYPD's video documentation.[175]

Eight men: Episcopalian Bishop George Packard, Mark Adams, Jack Boyle, Ed Mortimer, Ted Alexandro, John Lenmesin, Rev. Dr. Earl Koopercamp, and William Gusakov, all associated with Occupy Wall Street, were found guilty of misdemeanors stemming from a criminal trespass arrest on December 17, 2011. One of them, Mark Adams, was also convicted of attempted criminal mischief and attempted criminal possession of burglar’s tools for trying to slice a lock on a chain-link fence with bolt cutters. Adams was sentenced to 45 days imprisonment (he served 29 days); the other seven were convicted of criminal trespass and sentenced to community service.[176][177]

One defendant, Michael Premo, charged with assaulting an officer, was found not guilty of all charges after the defense presented video evidence which "showed officers charging into the defendant unprovoked." The video contradicted the sworn testimony of NYPD officers, who had claimed the defendant assaulted them.[178][179]

A court has ordered that the City pay $360,000 for their actions during the November 15, 2011 raid.[180] That case, Occupy Wall Street v. City of New York, was filed in the US District Court Southern District of New York.[181] Further, the City of New York has since begun settling cases with individual participants. The first of which was most notably represented by students of Hofstra Law School and the Occupy Wall Street Clinic.[182]

Nkrumah Tinsley was indicted on riot offenses and assaulting a police officer during the Zuccotti Park encampment. On May 21, 2013 Tinsley plead guilty to felony assault on a police officer, and will be sentenced later 2013.[183]

Notable responses

During an October 6 news conference, President Barack Obama said, "I think it expresses the frustrations the American people feel, that we had the biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression, huge collateral damage all throughout the country ... and yet you're still seeing some of the same folks who acted irresponsibly trying to fight efforts to crack down on the abusive practices that got us into this in the first place."[184][185]

On October 5, 2011, noted commentator and political satirist Jon Stewart said in his Daily Show broadcast: “If the people who were supposed to fix our financial system had actually done it, the people who have no idea how to solve these problems wouldn’t be getting shit for not offering solutions.” [186]

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney said that while there were "bad actors" that needed to be "found and plucked out", he believes that targeting one industry or region of America is a mistake and views encouraging the Occupy Wall Street protests as "dangerous" and inciting "class warfare".[187][188] Romney later expressed sympathy for the movement, saying, "I look at what's happening on Wall Street and my view is, boy, I understand how those people feel."[189]

House Democratic Leader Rep. Nancy Pelosi said she supports the Occupy Wall Street movement.[190] In September, various labor unions, including the Transport Workers Union of America Local 100 and the New York Metro 32BJ Service Employees International Union, pledged their support for demonstrators.[191]

Five days into the protest, political commentator Keith Olbermann, formerly of CurrentTV, vocally criticized mainstream media outlets for failing to cover the initial Wall Street protests and demonstrations adequately.[192][193]

On October 19, 2011, Greenpeace Executive Director Phil Radford spoke on behalf of Greenpeace supporting Occupy Wall Street protestors, stating: "We stand – as individuals and an organization – with Occupiers of all walks of life who peacefully stand up for a just, democratic, green and peaceful future."[194]

The Internet Archive and the Occupy Archive, a project at the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, has been collecting material from Occupy sites beyond New York.[195]

In November 2011, Public Policy Polling did a national survey which found that 33% of voters supported OWS and 45% opposed it, with 22% not sure. 43% of those polled had a higher opinion of the Tea Party movement than the Occupy movement.[196] In January 2012, a survey was released by Rasmussen Reports, in which 51% of likely voters found protesters to be a public nuisance, while 39% saw it as a valid protest movement representing the people.[197]

Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges, a supporter of the movement, argues that OWS had popular support and "articulated the concerns of the majority of citizens."[198]

Occupy Yale

In November 2011, some students started an Occupy Yale movement, discouraging fellow students from joining the finance sector.[199] 25% of Yale graduates join the financial sector.[200][201]

Government surveillance

As the movement spread across the United States, the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) began keeping tabs on protestors. A DHS report entitled "SPECIAL COVERAGE: Occupy Wall Street", dated October 2011, observed that "mass gatherings associated with public protest movements can have disruptive effects on transportation, commercial, and government services, especially when staged in major metropolitan areas."[202]

Crackdown

On December 29, 2012, Naomi Wolf of The Guardian newspaper provided U.S. government documents which revealed that the FBI and DHS had monitored Occupy Wall Street through its Joint Terrorism Task Force, despite labelling it a peaceful movement. The crackdown on protestors was coordinated with the big banks on Wall Street.[203] The FBI used counterterrorism agents to investigate the movement.[204]

Subsequent activity

To celebrate the third anniversary of the occupation, an Occupy Wall Street campaign called Strike Debt announced it had wiped out almost $4 million in student loans, amounting to the indebtedness of 2,761 students. The loans were all held by students of Everest College, a for profit college that operates Corinthian Colleges, Inc. which in turn owns Everest University, Everest Institute, Heald College, and WyoTech.

"We chose Everest because it is the most blatant con job on the higher ed landscape. It’s time for all student debtors to get relief from their crushing burden."

The loans became available when the banks holding defaulted loans put the bad loans up for sale. Once purchased, the group chose to forgive the loans. The funds to purchase the loans came from donations to the Rolling Jubilee Fund, part of the Occupy Student Debt program. As of September 2014, the group claimed to have wiped out almost $19 million in debt.[205]

That amount is a mere drop in the bucket compared to $1.2 Trillion in student debt that has been a drain on the American economic engine.[206] Most of these loans are protected by the federal government and are not available for purchase. Nor is bankruptcy protection available to the holders of those loans. The Occupy organization had previously purchased similar Medical debt loans in similar cents on the dollar arrangements. The group wanted to show examples of continuing economic inequality.

"We knew we wanted to focus on issues around for-profit education and looking at education as a commodity. The basic challenge is that we shouldn't need debt to finance basic necessities." "We can't solve the entire problem (of student debt) but we can help along the way while trying to fix the systemic problem"

— Laura Hanna, Strike Debt organizer[207]

See also

- Arab Spring

- Occupy movement

- 15 October 2011 global protests

- 1971 May Day Protests

- 2010–2011 Greek protests

- 2011–2012 Spanish protests

- 2011 United States public employee protests

- 2011 Wisconsin protests

- 2013 protests in Brazil

- 2013 protests in Turkey

- Bonus army 1932

- Poor People's Campaign 1968

- Radical media

- Cecily McMillan

- Thomas Piketty

- OWS Media Group

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ Author Dan Berrett writes: "But Occupy Wall Street's most defining characteristics—its decentralized nature and its intensive process of participatory, consensus-based decision-making—are rooted in other precincts of academe and activism: in the scholarship of anarchism and, specifically, in an ethnography of central Madagascar." [8]

- ^ The Huffington Post reports that Graeber and friends discovered that the "General Assembly" had been "taken over by a veteran protest group called the Worker's World Party". Graeber, his companions and others went off on their own to begin their own assembly. Eventually both factions came together. Matt Sledge of the Huffington Post writes: "As the meetings evolved, they became forums for people to air their grievances." There were about 200 activists who organized the ground rules 47 days before the protest began.[22]

Citations

- ^ Engler, Mark (November 1, 2011). "Let's end corruption – starting with Wall Street". New Internationalist Magazine (447). Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Hundreds of Occupy Wall Street protesters arrested". BBC News. October 2, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "700 Arrested After Wall Street Protest on N.Y.'s Brooklyn Bridge". Fox News Channel. October 1, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Gabbatt, Adam (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: protests and reaction Thursday 6 October". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 14, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ "Wall Street protests span continents, arrests climb". Archived from the original on November 18, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help), Crain's New York Business, October 17, 2011. - ^ Graeber, David (May 7, 2012). "Occupy's liberation from liberalism: the real meaning of May Day". Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 16, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- ^ "OccupyWallStreet - About". The Occupy Solidarity Network, Inc. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "Intellectual Roots of Wall St. Protest Lie in Academe — Movement's principles arise from scholarship on anarchy". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved February 23, 2012.

- ^ Revealed: how the FBI coordinated the crackdown on Occupy, The Guardian, Naomi Wolf, December 29, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2012/dec/29/fbi-coordinated-crackdown-occupy Template:WebCite

- ^ Moynihan, Colin. "Officials Cast Wide Net in Monitoring Occupy Protests." The New York Times. The New York Times, 22 May 2014. Web. 30 May 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/23/us/officials-cast-wide-net-in-monitoring-occupy-protests.html

- ^ a b c Schwartz, Mattathias (November 28, 2011). "Pre-Occupied". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ a b Fleming, Andrew (September 27, 2011). "Adbusters sparks Wall Street protest Vancouver-based activists behind street actions in the U.S". The Vancouver Courier. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- ^ "#OCCUPYWALLSTREET: A shift in revolutionary tactics". Adbusters. Archived from the original on November 15, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

- ^ Beeston, Laura (October 11, 2011). "The Ballerina and the Bull: Adbusters' Micah White on 'The Last Great Social Movement'". The Link. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Schneider, Nathan (September 29, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: FAQ". The Nation. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "The Tyee – Adbusters' Kalle Lasn Talks About OccupyWallStreet". Thetyee.ca. Archived from the original on February 16, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Press, Associated (August 2, 2011). "Wall Street naked performance art ends in arrests". CBC.ca. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ RYZIK, MELENA (August 1, 2011). "A Bare Market Lasts One Morning". New York Times. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "How a Canadian Culture Magazine Helped Spark Occupy Wall Street". 'Website publisher's name'. Retrieved July 26, 2012.

- ^ Occupy movement confronts limitations as it celebrates one year anniversary : VTDigger Archived 2014-05-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bennett, Drake (October 26, 2011). "David Graeber, the Anti-Leader of Occupy Wall Street". Business Week. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2012.: "While there were weeks of planning yet to go, the important battle had been won. The show would be run by horizontals, and the choices that would follow—the decision not to have leaders or even designated police liaisons, the daily GAs and myriad working-group meetings that still form the heart of the protests in Zuccotti Park—all flowed from that"

- ^ a b Sledge, Matt (November 10, 2011). "Reawakening The Radical Imagination: The Origins Of Occupy Wall Street". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Saba, Michael (September 17, 2011). "Twitter #occupywallstreet movement aims to mimic Iran". CNN tech. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ^ "Assange can still Occupy centre stage". Sydney Morning Herald. October 29, 2011. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "'Occupy Wall Street' to Turn Manhattan into 'Tahrir Square'". IBTimes New York. September 17, 2011. Archived from the original on May 21, 2012. Retrieved October 10, 2011.

- ^ "From a single hashtag, a protest circled the world". Brisbanetimes.com.au. October 19, 2011. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Batchelor, Laura (October 6, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street lands on private property". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Many of the Occupy Wall Street protesters might not realize it, but they got really lucky when they elected to gather at Zuccotti Park in downtown Manhattan

- ^ Schwartz, Mattathias (November 21, 2011). "Map: How Occupy Wall Street Chose Zuccotti Park". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Wall Street: 300 Years of Protests". Archived from the original on October 13, 2011. October 11, 2011 – By History.com Staff

- ^ "Occupy's new tactic has a powerful past". CNN. December 16, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. By Sonia K. Katyal and Eduardo M. Peñalver, Special to CNN December 16, 2011

- ^ "Wall Street protest's long historical roots". CNN. October 11, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2011. By Nicolaus Mills, Special to CNN October 11, 2011

- ^ Mills, Nicolaus (November 19, 2011). "A historical precedent that might prove a bonus for Occupy Wall Street". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. by Nicolaus Mills in The Guardian, Saturday November 19, 2011 "The Great Depression offers a striking parallel to this week's attack on Occupy Wall Street."

- ^ Apps, Peter (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street action part of global Arab Spring?". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ MD Conover & C Davis & E Ferrara & K McKelvey & F Menczer & A Flammini (2013). "The Geospatial Characteristics of a Social Movement Communication Network". PLoS ONE. 8 (3): e55957. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055957.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ MD Conover & E Ferrara & F Menczer & A Flammini (2013). "The Digital Evolution of Occupy Wall Street". PLoS ONE. 8 (5): e64679. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0064679.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Apps, Peter (October 11, 2011). "Wall Street action part of global Arab Spring?". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 18, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ Shenker, Jack; Gabbatt, Adam (October 25, 2011). "Tahrir Square protesters send message of solidarity to Occupy Wall Street". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. by Jack Shenker and Adam Gabbatt The Guardian, Tuesday October 25, 2011 "Much of the tactics, rhetoric and imagery deployed by protesters has clearly been inspired by this year's political upheavals in the Middle East..."

- ^ Toynbee, Polly (October 17, 2011). "In the City and Wall Street, protest has occupied the mainstream". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. By Polly Toynbee in The Guardian, Monday October 17, 2011 "From Santiago to Tokyo, Ottawa, Sarajevo and Berlin, spontaneous groups have been inspired by Occupy Wall Street."

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street: A protest timeline". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. "A relatively small gathering of young anarchists and aging hippies in lower Manhattan has spawned a national movement. What happened?"

- ^ a b Kara Bloomgarden-Smoke (January 29, 2012). "What's next for Occupy Wall Street? Activists target foreclosure crisis". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street's anarchist roots". Aljazeera. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2012. "It was only on August 2, when a small group of anarchists and other anti-authoritarians showed up at a meeting called by one such group and effectively wooed everyone away from the planned march and rally to create a genuine democratic assembly, on basically anarchist principles, that the stage was set for a movement that Americans from Portland to Tuscaloosa were willing to embrace."

- ^ Williams, Dana (2012). "The anarchist DNA of Occupy". Contexts. 11 (2): 19. doi:10.1177/1536504212446455.

- ^ Pearce, Matt (June 11, 2012). "Could the end be near for Occupy Wall Street movement?". LA Times. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2012.

- ^ a b "The Income Gap: Unfair, Or Are We Just Jealous?". Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. by Scott Horsley National Public Radia January 14, 2012

- ^ ""We Are the 99 Percent" Creators Revealed". Mother Jones and the Foundation for National Progress. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Sponsored by (October 26, 2011). "Income inequality in America: The 99 percent". The Economist. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ "Tax Data Show Richest 1 Percent Took a Hit in 2008, But Income Remained Highly Concentrated at the Top. Recent Gains of Bottom 90 Percent Wiped Out." "Center on Budget and Policy Priorities". Archived from the original on May 5, 2014.. Retrieved October 2011.

- ^ “By the Numbers.” "Demos.org". Archived from the original on May 12, 2014.. Retrieved October 2011.

- ^ Alessi, Christopher (October 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's Global Echo". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The Occupy Wall Street protests that began in New York City a month ago gained worldwide momentum over the weekend, as hundreds of thousands of demonstrators in nine hundred cities protested corporate greed and wealth inequality.

- ^ Jones, Clarence (October 17, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street and the King Memorial Ceremonies". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

The reality is that 'Occupy Wall Street' is raising the consciousness of the country on the fundamental issues of poverty, income inequality, economic justice, and the Obama administration's apparent double standard in dealing with Wall Street and the urgent problems of Main Street: unemployment, housing foreclosures, no bank credit to small business in spite of nearly three trillion of cash reserves made possible by taxpayers funding of TARP.

- ^ Chrystia Freeland (October 14, 2011). "Wall Street protesters need to find their 'sound bite'". The Globe and Mail. Toronto. Archived from the original on October 16, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ David R. Francis (January 24, 2012). "Thanks to Occupy, rich-poor gap is front and center. See Mitt Romney's tax return". CSMonitor.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ "Six in 10 Support Policies Addressing Income Inequality – ABC News". ABC News. November 9, 2011. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Seitz, Alex (October 31, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's Success: Even Republicans Are Talking About Income Inequality". ThinkProgress. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ http://people.umass.edu/adube/DubeKaplan_EV_OWS_2012.pdf

- ^ Media grows bored of Occupy - Salon.com Archived 2014-01-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Luhby, Tami (January 12, 2012). "Romney: Income inequality is just 'envy'". CNN. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013.

- ^ Scola, Nancy (October 5, 2011). "For the Anti-corporate Occupy Wall street demonstrators, the semi-corporate status of Zuccotti Park may be a boon". Capitalnewyork.com. Capital New York Media Group, Inc. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Occupy Wall Street: It's Not a Hippie Thing". Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. By Roger Lowenstein, Bloomberg Businessweek October 27, 2011

- ^ "Another idea for student loan debt: Make it go away". Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. By Petra Cahill Reporting for MSNBC, updated October 26, 2011

- ^ Baum, Geraldine (October 25, 2011). "Student loans add to angst at Occupy Wall Street". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Los Angeles Times By Geraldine Baum, October 25, 2011

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street vows to carry on after arrests". The San Francisco Chronicle. March 19, 2012. San Francisco Chronicle, Associated Press Monday, March 19, 2012

- ^ Valdes, Manuel (Associated Press) (December 6, 2011). "Occupy protests move to foreclosed homes". Yahoo! Finance. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Townsend, Mark; O'Carroll, Lisa; Gabbatt, Adam (October 15, 2011). "Occupy protests against capitalism spread around world". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013.

- ^ Linkins, Jason (October 27, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street: Not Here To Destroy Capitalism, But To Remind Us Who Saved It". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on October 31, 2011.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (October 26, 2011). "Crony Capitalism Comes Home". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- ^ Taibbi, Matt (October 25, 2011). "Wall Street Isn't Winning – It's Cheating". Rolling Stone Magazine. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Zizek, Slavoj (October 26, 2011). "Occupy first. Demands come later". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013.

- ^ Struck, Heather (October 19, 2011). "Europe's Occupy Wall Street Pokes At Anti-Capitalism Nerves". Forbes. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011.

- ^ Hoffman, Meredith (October 16, 2011). "New York Times". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013.

- ^ Walsh, Joan (October 20, 2011). "Do we know what OWS wants yet?". Salon.com. Archived from the original on September 2, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Mike Dunn, (City Hall Bureau Chief) KYW Newsradio (October 19, 2011). "'Occupy' May Hold National Assembly In Philadelphia". CBS Philly. Archived from the original on February 28, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- ^ a b Peralta, Eyder (February 24, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street Doesn't Endorse Philly Conference". npr.org. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2012.

- ^ "Occupy Protesters' One Demand: A New New Deal—Well, Maybe". Mother Jones. October 18, 2011. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- ^ Graeber, David. "Occupy Wall Street's Anarchist Roots". Al Jazeera English. Archived from the original on November 30, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ Elliott, Justin (October 24, 2011). "Judith Butler at Occupy Wall Street". Salon. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved May 20, 2012.; transcript of Butler's talk at http://occupywriters.com/works/by-judith-butler

- ^ Zuquete, Jose Pedro. 2012. "This is What Democracy Looks Like": Is Representation Under Siege?" Archived 2014-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kleinfield, N.R.; Buckley, Cara (September 30, 2011). "Wall Street Occupiers, Protesting Till Whenever". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2011.

- ^ "Protesters 'Occupy Wall Street' to Rally Against Corporate America". Archived from the original on December 14, 2013., Ray Downs, Christian Post, September 18, 2011

- ^ a b "Protesters Want World to Know They're Just Like Us". Archived from the original on May 7, 2012., Jocelyn Noveck, Associated Press via the Long Island Press, October 10, 2011

- ^ a b "Who is Occupy Wall Street? After six weeks, a profile finally emerges". Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. The Christian Science Monitor By Gloria Goodale, November 1, 2011

- ^ "Religion claims its place in Occupy Wall Street". Boston University. 2011. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

Inside, a Buddha statue sits near a picture of Jesus, while a hand-lettered sign in the corner points toward Mecca.

- ^ The rabbi's personal website, including links to various media reports of his activity with Occupy Wall Street Archived 2012-01-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Letter to Occupy Wall Street". Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. from www.nycga.net

- ^ Rabbi Gruber widely quoted in media reports about the 11/15/12 police raid on Zuccotti Park from www.haaretz.com

- ^ "Photo of Rabbi Gruber at Foley Sq., immediately following NYPD clearing of Zuccotti Park on Nov. 15, 2012". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. From www2.macleans.ca

- ^ "Infographic: Who Is Occupy Wall Street?". FastCompany.com. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ Parker, Kathleen (November 26, 2011). "Why African Americans aren't embracing Occupy Wall Street". Washington Post. Retrieved December 8, 2011.

- ^ 70% of #OWS Supporters are Politically Independent | OccupyWallSt.org By Occupywallst, OccupyWallSt.org October 19, 2011 Archived 2014-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Demographics Of Occupy Wall Street". Archived from the original on July 1, 2012. BY Sean Captain, Fast Company, October 19, 2011

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street Activists Aren't Quite What You Think: Report". Archived from the original on February 9, 2014.

- ^ Berman, Jillian (January 29, 2013). "Occupy Wall Street Activists Aren't Quite What You Think: Report". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013.

- ^ a b [1] By Professor Costas Panagopoulos, Fordham University, October 2011

- ^ Westfeldt, Amy (December 15, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street's center shows some cracks". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on May 2, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2012.

- ^ Hinkle, A. Barton (November 4, 2011). "OWS protesters have strange ideas about fairness". Richmond Times Dispatch. Archived from the original on August 15, 2012. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Penny, Laura (October 16, 2011). "Protest By Consensus". New Statesman. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Jeremy B. White (October 25, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street Expands, Tensions Mount Over Structure". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street's Media Team". Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database. October 5, 2011. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ "New York City General Assembly website". Archived from the original on February 23, 2014.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street Moves Indoors With Spokes Council". The New York Observer. November 8, 2011. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street takes a new direction". Crain Communications Inc. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ "Does 'Occupy Wall Street' have leaders? Does it need any?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Astor, Maggie (October 4, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street Protests: A Fordham University Professor Analyzes the Movement". International Business Times. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

Fordham University Sociologist Heather Gautney in an interview with the International Business Times 'the movement doesn't have leaders, but it certainly has organizers, and there are certainly people providing a human structure to this thing. There might not be these kinds of public leaders, but there are people running it, and I think that's inevitable.'

- ^ Giove, Candice (January 8, 2012). "OWS has money to burn". New York Post. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012.

- ^ The Single Largest Benefactor of Occupy Wall Street Is a Mitt Romney Donor Archived 2014-03-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Burruss, Logan (November 21, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street has money to burn". CNN. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Expenditures | Accounting". Accounting.nycga.net. October 15, 2011. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Firger, Jessica (February 28, 2012). "Occupy Groups Get Funding". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle (March 9, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street in New York running low on cash". Reuters. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014.

- ^ Cabrera, Claudio. "Is Occupy Wall Street Running Out of Money?". Archived from the original on June 7, 2012.

- ^ Nichols, Michelle (March 9, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street in New York running out of cash". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ Firger, Jessica (February 28, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street Movement Gets Corporate Support". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Simon, Scott. "Ben And Jerry Raise Dough For Occupy Movement". NPR. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- ^ Farnham, Alan. "Springtime for Occupy: Movement's Plans For Coming Weeks and Months". ABC News. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Zabriskie, Christian (November 16, 2011). "The Occupy Wall Street Library Regrows in Manhattan". American Libraries. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ "ALA alarmed at seizure of Occupy Wall Street library, loss of irreplaceable material" (Press release). American Library Association. November 17, 2011. Archived from the original on November 19, 2011. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ^ A Library Occupies the Heart of the Occupy Movement | American Libraries Magazine Template:WebCite

- ^ "Somewhere between 100 and 200 people sleep in Zuccotti Park...." "Many occupiers were still in their sleeping bags at 9 or 10 am" Wall Street functions like a small city, Associated Press, October 7, 2011

- ^ a b Anne Kadet (October 15, 2011). "The Occupy Economy". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- ^ Oloffson, Kristi (October 12, 2011). "Food Vendors Find Few Customers During Protest". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 24, 2011.

- ^ GIOVE, CANDICE (November 13, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street costs local businesses $479,400!". New York Post. Archived from the original on February 19, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ Rosenberg, Rebecca (October 19, 2011). "Protest mob is enjoying rich diet". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 22, 2011.

- ^ Selim Algar and Bob Fredricks (October 27, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street kitchen staff protesting fixing food for freeloaders". New York Post. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013.

- ^ Kadet, Anne (October 15, 2011). "The Occupy Economy". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- ^ Richard Kim on (October 3, 2011). "We Are All Human Microphones Now". The Nation. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "A general assembly of anyone who wants to attend meets twice daily. Because it's hard to be heard above the din of lower Manhattan and because the city is not allowing bullhorns or microphones, the protesters have devised a system of hand symbols. Fingers downward means you disagree. Arms crossed means you strongly disagree. Announcements are made via the "people's mic... you say it and the people immediately around you repeat it and pass the word along. "Wall Street functions like a small city", Associated Press, October 7, 2011

- ^ "Behind the sign marked “info” sat computers, , generators, wireless routers, and lots of electrical cords. This is the media center, where the protesters group and distribute their messages. Those who count themselves among the media team for Occupy Wall Street are self-appointed; the same goes with all teams within this community." ""I later learned that power comes from a gas-powered generator which runs, among other things, multiple 4G wireless Internet hotspots that provide Internet access to the scrappy collection of laptops." "Occupy Wall Street's Media Team". Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database. October 5, 2011. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ "The Technology Propelling #OccupyWallStreet". Daily Mail. October 6, 2011. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- ^ Esmé E. Deprez and Charles Mead (October 28, 2011). "New York Authorities Remove Fuel, Generators From Occupy Wall Street Site". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on December 29, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

- ^ Gambs, Deborah (2012). "Occupying Social Media". Socialism and Democracy. 26 (2). doi:10.1080/08854300.2012.686275. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ Colin Moynihan (October 30, 2011). "With Generators Gone, Wall Street Protesters Try Bicycle Power". New York Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2013.

- ^ "as the protest has grown, the media team has been busy coordinating, notably through the “unofficial,” Occupytogether.org. It’s a hub for all Occupy-inspired happenings and updates, a key part of the internal communications network for the Occupy demonstrations. While sitting in the media tent I saw several Skype sessions with other demonstrators. At one point a bunch of people gathered around a computer shouting, “Hey Scotland!” Members of the media team also maintain a livestream, and keep a steady flow of updates on Twitter, Facebook, and Tumblr." "Occupy Wall Street's Media Team". Columbia Journalism Review's New Frontier Database. October 5, 2011. Archived from the original on December 14, 2013.

- ^ "Kelly: Protesters To Be 'Met With Force' If They Target Officers". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014., CBS News, October 6, 2011

- ^ Grossman, Andrew (September 26, 2011). "Protest Has Unlikely Host". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ a b Allison Kilkenny on. "Occupy Wall Street Protesters Win Showdown With Bloomberg". The Nation. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Cleanup Canceled". BusinessWeek. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013.

- ^ Deprez, Esmé E., Joel Stonington and Chris Dolmetsch, "Occupy Wall Street Park Cleaning Postponed". Bloomberg. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on December 29, 2013.

- ^ Kaufman, Gill (October 24, 2011). "MTV's 'True Life' To Explore Occupy Wall Street". MTV. Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Saul, Josh (October 21, 2011). "Angry Manhattan residents lambast Zuccotti Park protesters". The New York Post. Archived from the original on March 28, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ Walker, Jade (November 15, 2011). "Zuccotti Park Eviction: NYPD Orders Occupy Wall Street Protesters To Temporarily Evacuate Park [LATEST UPDATES]". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ CNN Wire Staff (November 15, 2011). "New York court upholds eviction of "Occupy" protesters". CNN. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

A New York Supreme Court has ruled not to extend a temporary restraining order that prevented the eviction of "Occupy" protesters who were encamped at Zuccotti Park, considered a home-base for demonstrators. Police in riot gear cleared out the protesters early Tuesday morning, a move that attorneys for the loosely defined group say was unlawful. But Justice Michael Stallman later ruled in favor of New York city officials and Brookfield properties, owners and developers of the privately owned park in Lower Manhattan. The order does not prevent protesters from gathering in the park, but says their First Amendment rights not do include remaining there, "along with their tents, structures, generators, and other installations to the exclusion of the owner's reasonable rights and duties to maintain Zuccotti Park."

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help); line feed character in|quote=at position 208 (help) - ^ Paddock, Barry; Mcshane, Larry (January 1, 2012). "Protesters Occupy New Year in Zuccotti Park". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "OWS Clash With Police At Zuccotti Park". Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Mathias, Christopher (January 12, 2012). "After Occupy Wall Street Encampment Ends, NYC Protesters Become Nomads". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 19, 2013. Retrieved January 30, 2012.

- ^ Colvin, Jill. "Occupy Wall Street Cost NYPD $17 Million in Overtime". Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Goldenberg, Sally (March 16, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street cost the NYPD $17 million in overtime, Ray Kelly said". New York Post. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Joe Kemp (March 16, 2012). "OWS protests cost city $17M in OT – Kelly – New York Daily News". Articles.nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (March 17, 2012). "Scores Arrested as the Police Clear Zuccotti Park". The New York Times. Zuccotti Park (NYC). Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ^ Ryan Devereaux (March 18, 2012). "Dozens arrested as Occupy Wall Street marks anniversary with fresh protests". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ Devereaux, Ryan (March 24, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street demonstrators march to protest against police violence". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on June 11, 2013.

- ^ Moynihan, Colin (September 17, 2012). "185 Arrested on Occupy Wall St. Anniversary". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 9, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ Barr, Meghan (September 17, 2012). "1-year after encampment began, Occupy in disarray". Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ Walker, Hunter (September 18, 2012). "Unoccupied: The Morning After in Zuccotti Park". Politicker Network. Observer.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved September 26, 2012.

- ^ Coscarelli, Joe (September 18, 2012). "NYPD Arrests Almost 200 Occupy Protesters, Roughs Up City Councilman Again". New York. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Celona, Larry (October 18, 2011). "Thieves preying on fellow protesters". New York Post. Archived from the original on September 2, 2013.

- ^ Siegal, Ida. "Man Arrested for Breaking EMT's Leg at Occupy Wall Street". NBC New York. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2011.

- ^ "Michael Bloomberg: Crime at Occupy Wall Street goes unreported". Free Daily News Group Inc. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street protesters at odds with Mayor Bloomberg, NYPD over crime in Zuccotti Park". Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Wall Street Erects Women-Only Tent After Reports Of Sexual Assaults". The Gothamist News. Archived from the original on June 2, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Schram, Jamie (November 3, 2011). "Protester busted in tent grope, suspected in rape of another demonstrator". NY POST. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Man Arrested For Groping Protester Also Eyed In Zuccotti Park Rape Case". WPIX. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Dejohn, Irving; Kemp, Joe (November 2, 2011). "Arrest made in Occupy Wall St. sex attack; Suspect eyed in another Zuccotti gropingCase". New York: NY Daily News. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Protests Plagued by Reports of Sex Attacks, Violent Crime". NY Daily News. November 9, 2011. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

- ^ Michael Hastings (November 16, 2011). "Exclusive: Homeland Security Kept Tabs on Occupy Wall Street | Politics News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Leopold, Jason (March 20, 2012). "DHS Turns Over Occupy Wall Street Documents to Truthout". Truth-out.org. Archived from the original on April 9, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "700 arrested at Brooklyn Bridge protest". CBS News. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013.

- ^ "Most Popular E-mail Newsletter". USA Today. October 2, 2011.

- ^ Baker, Al (October 1, 2011). "Police Arrest More Than 400 Protesters on Brooklyn Bridge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2011.

- ^ Pilkington, Ed (October 2, 2011). "Occupy Wall Street protest: NYPD accused of heavy-handed tactics". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011.

- ^ "Hundreds freed after New York Wall Street protest". BBC News. BBC. October 2, 2011. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 2, 2011.

- ^ ELIZABETH A. HARRIS (October 5, 2011). "Citing Police Trap, Protesters File Suit". The New York Times. p. A25. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ^ Devereaux, Ryan (June 8, 2012). "Occupy Wall Street protesters win legal victory in Brooklyn bridge arrests". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013.

- ^ Kilkenny, Allison (May 25, 2012). "Third Case Against Occupy Wall Street Protester Is Thrown Out". The Nation Magazine. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Pinto, Nick (May 16, 2012). "In The First Occupy Wall Street Protest Trial, Acquittal". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Pinto, Nick (May 17, 2012). "In Second Occupy Wall Street Protest Trial, Police Claims Again Rejected". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Occupy trespassers guilty". New York Post. June 19, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Pinto, Nick (June 19, 2012). "Eight Occupy Wall Street Protesters Found Guilty of Trespassing, One Sentenced To 45 Days In Jail". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 27, 2013. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ Jury Finds Occupy Wall Street Protester Innocent After Video Contradicts Police Testimony [Updated: VIDEO] - New York - News - Runnin' Scared Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NYPD lied under oath to prosecute Occupy activist — RT USA Archived 2014-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Court orders NYPD to pay $360,000 for raid that destroyed Occupy Wall Street library | The Raw Story Archived 2013-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ruling

- ^ Hofstra Law's Occupy Wall Street Clinic Settles First Case Against the City of New York - Maurice A. Deane School of Law - Hofstra University. Law.hofstra.edu (October 26, 2011). Retrieved on August 12, 2013. Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NYS Court's official website | log on as public user, type in defendant's name, and look at the charges Archived 2013-08-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Memoli, Michael A. (July 13, 2011). "Obama news conference: Obama: Occupy Wall Street protests show Americans' frustration". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2011. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Salazar, Cristian (October 6, 2011). "Obama acknowledges Wall Street protests as a sign". BusinessWeek. Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- ^ Jon, Stewart. "The Daily Show". Archived from the original on October 7, 2011.

- ^ WCVBtv. "Romney On Occupy Wall Street Protests". YouTube. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Boxer, Sarah (October 5, 2011). "Romney: Wall Street Protests 'Class Warfare'". National Journal. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ Geiger, Kim (October 11, 2011). "Mitt Romney sympathizes with Wall Street protesters". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2011.