Western Wall

הכותל המערבי (HaKotel HaMa'aravi) | |

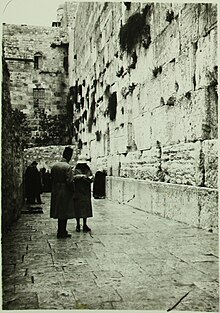

A view of the Western Wall | |

| Alternative name | [The] Wailing Wall [The] Kotel Al-Buraq Wall الْحَائِط ٱلْبُرَاق (Ḥā’iṭ al-Burāq) |

|---|---|

| Location | Jerusalem |

| Coordinates | 31°46′36″N 35°14′04″E / 31.7767°N 35.2345°E |

| Type | Ancient limestone wall |

| Part of | Temple Mount |

| Length | 488 metres (1,601 ft) |

| Height | Exposed: 19 metres (62 ft) |

| History | |

| Builder | Herod the Great |

| Material | Limestone |

| Founded | 19 BCE |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | Preserved |

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

|

The Western Wall (Hebrew: הַכּוֹתֶל הַמַּעֲרָבִי, romanized: HaKotel HaMa'aravi, lit. 'the western wall',[1] is an ancient retaining wall of the built-up hill known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount of Jerusalem. Its most famous section, known by the same name, often shortened by Jews to the Kotel or Kosel, is known in the West as the Wailing Wall, and in Islam as the Buraq Wall (Arabic: حَائِط ٱلْبُرَاق, Ḥā'iṭ al-Burāq ['ħaːʔɪtˤ albʊ'raːq]). In a Jewish religious context, the term Western Wall and its variations is used in the narrow sense, for the section used for Jewish prayer; in its broader sense it refers to the entire 488-metre-long (1,601 ft) retaining wall on the western side of the Temple Mount.

At the prayer section, just over half the wall's total height, including its 17 courses located below street level, dates from the end of the Second Temple period, and is believed to have been begun by Herod the Great.[2] The very large stone blocks of the lower courses are Herodian, the courses of medium-sized stones above them were added during the Umayyad period, while the small stones of the uppermost courses are of more recent date, especially from the Ottoman period.

The Western Wall plays an important role in Judaism due to it being part of the man-made "Temple Mount", an artificially expanded hilltop best known as the traditional site of the Jewish Temple. Because of the Temple Mount entry restrictions, the Wall is the holiest place where Jews are permitted to pray outside the Temple Mount platform, because the presumed site of the Holy of Holies, the most sacred site in the Jewish faith, presumably lies just above and behind it. The original, natural, and irregular-shaped Temple Mount was gradually extended to allow for an ever-larger Temple compound to be built at its top. The earliest source possibly mentioning this specific site as a place of Jewish worship is from the 10th century.[3][4] The Western Wall, in the narrow sense, i.e. referring to the section used for Jewish prayer, is also known as the "Wailing Wall", in reference to the practice of Jews weeping at the site. During the period of Christian Roman rule over Jerusalem (ca. 324–638), Jews were completely barred from Jerusalem except on Tisha B'Av, the day of national mourning for the Temples. The term "Wailing Wall" has historically been used mainly by Christians, with use by Jews becoming marginal.[5] Of the entire retaining wall, the section ritually used by Jews now faces a large plaza in the Jewish Quarter, near the southwestern corner of the Temple Mount, while the rest of the wall is concealed behind structures in the Muslim Quarter, with the small exception of an 8-metre (26 ft) section, the so-called "Little Western Wall" or "Small Wailing Wall". This segment of the western retaining wall derives particular importance from having never been fully obscured by medieval buildings, and displaying much of the original Herodian stonework. In religious terms, the "Little Western Wall" is presumed to be even closer to the Holy of Holies and thus to the "presence of God" (Shechina), and the underground Warren's Gate, which has been out of reach for Jews from the 12th century till its partial excavation in the 20th century.

The entire Western Wall constitutes the western border of al-Haram al-Sharif ("the Noble Sanctuary"), or the Al-Aqsa compound. It is believed to be the site where the Islamic Prophet Muhammad tied his winged steed, the Burāq, on his Night Journey, which tradition connects to Jerusalem, before ascending to heaven. While the wall was considered an integral part of the Haram esh-Sharif and waqf property of the Moroccan Quarter under Muslim rule, a right of Jewish prayer and pilgrimage has long existed as part of the Status Quo regulations.[6][7][8] This position was confirmed in a 1930 international commission during the British Mandate period.

With the rise of the Zionist movement in the early 20th century, the wall became a source of friction between the Jewish and Muslim communities, the latter being worried that the wall could be used to further Jewish claims to the Temple Mount and thus Jerusalem. During this period outbreaks of violence at the foot of the wall became commonplace, with a particularly deadly riot in 1929 in which 133 Jews and 116 Arabs were killed, with many more people injured. After the 1948 Arab–Israeli War the eastern portion of Jerusalem was occupied by Jordan. Under Jordanian control Jews were completely expelled from the Old City including the Jewish Quarter, and Jews were barred from entering the Old City for 19 years, effectively banning Jewish prayer at the site of the Western Wall. This period ended on June 10, 1967, when Israel gained control of the site following the Six-Day War. Three days after establishing control over the Western Wall site, the Moroccan Quarter was bulldozed by Israeli authorities to create space for what is now the Western Wall plaza.[9]

Etymology

Western Wall

Early Jewish texts referred to a "western wall of the Temple",[10] but there is doubt whether the texts were referring to the outer, retaining wall called today "the Western Wall", or to the western wall of the actual Temple.[5] The earliest Jewish use of the Hebrew term "ha-kotel ha-ma'aravi", "the Western Wall", as referring to the wall visible today, was by the 11th-century poet Ahimaaz ben Paltiel.[5]

Wailing Wall

The name "Wailing Wall", and descriptions such as "wailing place", appeared regularly in English literature during the 19th century.[11][12][13] The name Mur des Lamentations was used in French and Klagemauer in German. This description stemmed from the Jewish practice of coming to the site to mourn and bemoan the destruction of the Temple and the loss of national freedom it symbolized.[5]

Jews may often be seen sitting for hours at the Wailing-place bent in sorrowful meditation over the history of their race, and repeating oftentimes the words of the Seventy-ninth Psalm. On Fridays especially, Jews of both sexes, of all ages, and from all countries, assemble in large numbers to kiss the sacred stones and weep outside the precincts they may not enter.

Charles Wilson, 1881[14]

Al-Buraq Wall

Muslims have associated the name Al-Buraq with the wall at least since the 1860s.[15]

Location, dimensions, stones

Prayer section vs. entire wall

The term Western Wall commonly refers to a 187-foot (57 m) exposed section of a much longer retaining wall, built by Herod on the western flank of the Temple Mount. Only when used in this sense is it synonymous with the term Wailing Wall. This section faces a large plaza and is set aside for prayer.

In its entirety, the western retaining wall of the Herodian Temple Mount complex stretches for 1,600 feet (488 m), most of which is hidden behind medieval residential structures built along its length.

There are only two other revealed sections: the southern part of the Wall (see Robinson's Arch area), which measures approximately 80 metres (262 ft), and is separated from the prayer area by just a narrow stretch of archaeological remains; and another, much shorter section, known as the Little Western Wall, which is located close to the Iron Gate.

The entire western wall functions as a retaining wall, supporting and enclosing the ample substructures built by Herod the Great around 19 BCE. Herod's project was to create an artificial extension to the small quasi-natural plateau on which the First Temple stood, already widened in Hasmonean times during the Second Temple period, by finally transforming it into the almost rectangular, wide expanse of the Temple Mount platform visible today.

Height, courses, building stones

At the Western Wall Plaza, the total height of the Wall from its foundation is estimated at 105 feet (32 m), with the above-ground section standing approximately 62 feet (19 m) high. The Wall consists of 45 stone courses, 28 of them above ground and 17 underground.[16] The first seven above-ground layers are from the Herodian period. This section of wall is built from enormous meleke limestone blocks, possibly quarried at either Zedekiah's Cave[17] situated under the Muslim Quarter of the Old City, or at Ramat Shlomo[18] 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) northwest of the Old City. Most of them weigh between 2 and 8 short tons (1.8 and 7.3 tonnes) each, but others weigh even more, with one extraordinary stone located slightly north of Wilson's Arch[19] measuring 13.55 metres (44.5 ft) long, 3.3 metres (11 ft) high,[20] approximately 1.8 to 2.5 metres (5.9 to 8.2 ft) deep,[21][22] and weighing between 250 and 300 tonnes (280 and 330 short tons).[22] Each of these ashlars is framed by fine-chiseled borders. The margins themselves measure between 5 and 20 centimetres (2 and 8 in) wide, with their depth measuring 1.5 centimetres (0.59 in). In the Herodian period, the upper 10 metres (33 ft) of wall were 1 metre (39 in) thick and served as the outer wall of the double colonnade of the Temple platform. This upper section was decorated with pilasters, the remainder of which were destroyed when the Byzantines reconquered Jerusalem from the Persians in 628.[19]

The next four courses, consisting of smaller plainly dressed stones, are Umayyad work (8th century, Early Muslim period).[23] Above that are 16 to 17 courses of small stones from the Mamluk period (13th–16th centuries) and later.[23]

History

Construction and destruction (19 BCE–70 CE)

According to the Hebrew Bible, Solomon's Temple was built atop what is known as the Temple Mount in the 10th century BCE and destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE,[24] and the Second Temple completed and dedicated in 516 BCE. Around 19 BCE Herod the Great began a massive expansion project on the Temple Mount. In addition to fully rebuilding and enlarging the Temple, he artificially expanded the platform on which it stood, doubling it in size. Today's Western Wall formed part of the retaining perimeter wall of this platform. In 2011, Israeli archaeologists announced the surprising discovery of Roman coins minted well after Herod's death, found under the foundation stones of the wall. The excavators came upon the coins inside a ritual bath that predates Herod's building project, which was filled in to create an even base for the wall and was located under its southern section.[25] This seems to indicate that Herod did not finish building the entire wall by the time of his death in 4 BCE. The find confirms the description by historian Josephus Flavius, which states that construction was finished only during the reign of King Agrippa II, Herod's great-grandson.[26] Given Josephus' information, the surprise mainly regarded the fact that an unfinished retaining wall in this area could also mean that at least parts of the splendid Royal Stoa and the monumental staircase leading up to it could not have been completed during Herod's lifetime. Also surprising was the fact that the usually very thorough Herodian builders had cut corners by filling in the ritual bath, rather than placing the foundation course directly onto the much firmer bedrock. Some scholars are doubtful of the interpretation and have offered alternative explanations, such as, for example, later repair work.

Herod's Temple was destroyed by the Romans, along with the rest of Jerusalem, in 70 CE,[27] during the First Jewish–Roman War.

Late Roman and Byzantine periods (135–638)

During much of the 2nd–5th centuries of the Common Era, after the Roman defeat of the Bar Kokhba revolt in 135 CE, Jews were banned from Jerusalem. There is some evidence that Roman emperors in the 2nd and 3rd centuries did permit them to visit the city to worship on the Mount of Olives and sometimes on the Temple Mount itself.[28] When the empire started becoming Christian under Constantine I, they were given permission to enter the city once a year, on the Tisha B'Av, to lament the loss of the Temple at the wall.[29] The Bordeaux Pilgrim, who wrote in 333 CE, suggests that it was probably to the perforated stone or the Rock of Moriah, "to which the Jews come every year and anoint it, bewail themselves with groans, rend their garments, and so depart".This was because an imperial decree from Rome barred Jews from living in Jerusalem. Just once per year they were permitted to return and bitterly grieve about the fate of their people. Comparable accounts survive, including those by the Church Father, Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390) and by Jerome in his commentary to Zephaniah written in 392 CE. In the 4th century, Christian sources reveal that the Jews encountered great difficulty in buying the right to pray near the Western Wall, at least on the 9th of Av.[28] In 425 CE, the Jews of the Galilee wrote to Byzantine empress Aelia Eudocia seeking permission to pray by the ruins of the Temple. Permission was granted and they were officially permitted to resettle in Jerusalem.[30]

Archaeology

Discovery of underground rooms that could have been used as food storage carved out of the bedrock under the 1,400-year-old mosaic floor of Byzantine structure was announced by Israel Antiquities Authority in May in 2020.

"At first we were very disappointed because we found we hit the bedrock, meaning that the material culture, the human activity here in Jerusalem ended. What we found here was a rock-cut system—three rooms, all hewn in the bedrock of ancient Jerusalem" said co-director of the excavation Barak Monnickendam-Givon.[31]

Early Muslim to Mamluk period (638–1517)

Several Jewish authors of the 10th and 11th centuries write about the Jews resorting to the Western Wall for devotional purposes.[32][4] Ahimaaz relates that Samuel ben Paltiel (980–1010) gave money for oil at "the sanctuary at the Western Wall."[33][34][35] Benjamin of Tudela (1170) wrote "In front of this place is the western wall, which is one of the walls of the Holy of Holies. This is called the Gate of Mercy, and hither come all the Jews to pray before the Wall in the open court." The account gave rise to confusion about the actual location of Jewish worship, and some suggest that Benjamin in fact referred to the Eastern Wall along with its Gate of Mercy.[36][37] While Nahmanides (d. 1270) did not mention a synagogue near the Western Wall in his detailed account of the temple site,[38] shortly before the Crusader period a synagogue existed at the site.[39] Obadiah of Bertinoro (1488) states "the Western Wall, part of which is still standing, is made of great, thick stones, larger than any I have seen in buildings of antiquity in Rome or in other lands."[40]

Shortly after Saladin's 1187 siege of the city, in 1193, the sultan's son and successor al-Afdal established the land adjacent to the wall as a charitable trust (waqf). The largest part of it was named after an important mystic, Abu Madyan Shu'aib. The Abu Madyan waqf was dedicated to Maghrebian pilgrims and scholars who had taken up residence there, and houses were built only metres away from the wall, from which they were thus separated by just a narrow passageway,[41] some 4 metres (13 ft) wide.[citation needed]

The first likely mention of the Islamic tradition that Buraq was tethered at the site is from the 14th century. A manuscript by Ibrahim b. Ishaq al-Ansari (known as Ibn Furkah, d. 1328) refers to Bab al-Nabi (lit. "Gate of the Prophet"), an old name for Barclay's Gate below the Maghrebi Gate.[42][43] Charles D. Matthews however, who edited al-Firkah's work, notes that other statements of al-Firkah might seem to point to the Double Gate in the southern wall.[44]

Ottoman period (1517–1917)

In 1517, the Turkish Ottomans under Selim I conquered Jerusalem from the Mamluks who had held it since 1250. Selim's son, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, ordered the construction of an imposing wall to be built around the entire city, which still stands today. Various folktales relate Suleiman's quest to locate the Temple site and his order to have the area "swept and sprinkled, and the Western Wall washed with rosewater" upon its discovery.[45] According to a legend cited by Moses Hagiz, Jews received official permission to worship at the site and Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan built an oratory for them there,[46] but, as of Purim 1625, Jews were banned from praying on the Temple Mount and only sometimes dared to pray at the Western Wall, for which purpose a special liturgy had been arranged.[47] Gedaliah of Siemiatycze, who lived in Jerusalem from 1700 to 1706, reports that Jews then had access to the wall and would pray there as often as possible.[48]

Over the centuries, land close to the Wall became built up. Public access to the Wall was through the Moroccan Quarter, a labyrinth of narrow alleyways. In May 1840 a firman issued by Ibrahim Pasha forbade the Jews to pave the passageway in front of the Wall. It also cautioned them against "raising their voices and displaying their books there." They were, however, allowed "to pay visits to it as of old."[4]

Rabbi Joseph Schwarz writing in the mid-19th century records:

This wall is visited by all our brothers on every feast and festival; and the large space at its foot is often so densely filled up, that all cannot perform their devotions here at the same time. It is also visited, though by less numbers, on every Friday afternoon, and by some nearly every day. No one is molested in these visits by the Mahomedans, as we have a very old firman from the Sultan of Constantinople that the approach shall not be denied to us, though the Porte obtains for this privilege a special tax, which is, however, quite insignificant.[49]

Over time the increased numbers of people gathering at the site resulted in tensions between the Jewish visitors who wanted easier access and more space, and the residents, who complained of the noise.[4] This gave rise to Jewish attempts at gaining ownership of the land adjacent to the Wall.

In the late 1830s a wealthy Jew named Shemarya Luria attempted to purchase houses near the Wall, but was unsuccessful,[50] as was Jewish sage Abdullah of Bombay who tried to purchase the Western Wall in the 1850s.[51] In 1869 Rabbi Hillel Moshe Gelbstein settled in Jerusalem. He arranged that benches and tables be brought to the Wall on a daily basis for the study groups he organised and the minyan which he led there for years. He also formulated a plan whereby some of the courtyards facing the Wall would be acquired, with the intention of establishing three synagogues—one each for the Sephardim, the Hasidim and the Perushim.[52] He also endeavoured to re-establish an ancient practice of "guards of honour", which according to the mishnah in Middot, were positioned around the Temple Mount. He rented a house near the Wall and paid men to stand guard there and at various other gateways around the mount. However, this set-up lasted only for a short time due to lack of funds or because of Arab resentment.[53] In 1874, Mordechai Rosanes paid for the repaving of the alleyway adjacent to the wall.[54]

In 1887 Baron Rothschild conceived a plan to purchase and demolish the Moroccan Quarter as "a merit and honor to the Jewish People."[55] The proposed purchase was considered and approved by the Ottoman Governor of Jerusalem, Rauf Pasha, and by the Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammed Tahir Husseini. Even after permission was obtained from the highest secular and Muslim religious authority to proceed, the transaction was shelved after the authorities insisted that after demolishing the quarter no construction of any type could take place there, only trees could be planted to beautify the area. Additionally the Jews would not have full control over the area. This meant that they would have no power to stop people from using the plaza for various activities, including the driving of mules, which would cause a disturbance to worshippers.[55] Other reports place the scheme's failure on Jewish infighting as to whether the plan would foster a detrimental Arab reaction.[56]

In 1895 Hebrew linguist and publisher Rabbi Chaim Hirschensohn became entangled in a failed effort to purchase the Western Wall and lost all his assets.[57] The attempts of the Palestine Land Development Company to purchase the environs of the Western Wall for the Jews just before the outbreak of World War I also never came to fruition.[51] In the first two months following the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War, the Turkish governor of Jerusalem, Zakey Bey, offered to sell the Moroccan Quarter, which consisted of about 25 houses, to the Jews in order to enlarge the area available to them for prayer. He requested a sum of £20,000 which would be used to both rehouse the Muslim families and to create a public garden in front of the Wall. However, the Jews of the city lacked the necessary funds. A few months later, under Muslim Arab pressure on the Turkish authorities in Jerusalem, Jews became forbidden by official decree to place benches and light candles at the Wall. This sour turn in relations was taken up by the Chacham Bashi who managed to get the ban overturned.[58] In 1915 it was reported that Djemal Pasha, closed off the wall to visitation as a sanitary measure.[59] Probably meant was the "Great", rather than the "Small" Djemal Pasha.

Decrees (firman)s issued regarding the Wall:

| Year | Issued by | Content |

|---|---|---|

| c. 1560 | Suleiman the Magnificent | Official recognition of the right of Jews to pray by the Wall[60][61] |

| 1840 | Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt | Forbidding the Jews to pave the passage in front of the Wall. It also cautioned them against "raising their voices and displaying their books there." They were, however, allowed "to pay visits to it as of old."[4] |

| 1841* | Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt | "Of the same bearing and likewise to two others of 1893 and 1909"[4] |

| 1889* | Abdul Hamid II | That there shall be no interference with the Jews' places of devotional visits and of pilgrimage, that are situated in the localities which are dependent on the Chief Rabbinate, nor with the practice of their ritual.[4] |

| 1893* | Confirming firman of 1889[4] | |

| 1909* | Confirming firman of 1889[4] | |

| 1911 | Administrative Council of the Liwa | Prohibiting the Jews from certain appurtenances at the Wall[4] |

- These firmans were cited by the Jewish contingent at the International Commission, 1930, as proof for rights at the Wall. Muslim authorities responded by arguing that historic sanctions of Jewish presence were acts of tolerance shown by Muslims, who, by doing so, did not concede any positive rights.[62]

British rule (1917–48)

In December 1917, Allied forces under Edmund Allenby captured Jerusalem from the Turks. Allenby pledged "that every sacred building, monument, holy spot, shrine, traditional site, endowment, pious bequest, or customary place of prayer of whatsoever form of the three religions will be maintained and protected according to the existing customs and beliefs of those to whose faith they are sacred".[63]

In 1919 Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann approached the British Military Governor of Jerusalem, Colonel Sir Ronald Storrs, and offered between £75,000[64] and £100,000[65] (approx. £5m in modern terms) to purchase the area at the foot of the Wall and rehouse the occupants. Storrs was enthusiastic about the idea because he hoped some of the money would be used to improve Muslim education. Although they appeared promising at first, negotiations broke down after strong Muslim opposition.[65][66] Storrs wrote two decades later:

The acceptance of the proposals, had it been practicable, would have obviated years of wretched humiliations, including the befouling of the Wall and pavement and the unmannerly braying of the tragi-comic Arab band during Jewish prayer, and culminating in the horrible outrages of 1929.[64]

In early 1920, the first Jewish-Arab dispute over the Wall occurred when the Muslim authorities were carrying out minor repair works to the Wall's upper courses. The Jews, while agreeing that the works were necessary, appealed to the British that they be made under supervision of the newly formed Department of Antiquities, because the Wall was an ancient relic.[67]

According to Hillel Halkin, in the 1920s, among rising tensions with the Jews regarding the wall, the Arabs ceased using the more traditional name El-Mabka, "the Place of Weeping", which related to Jewish practices, and replaced it with El-Burak, a name with Muslim connotations.[5]

In 1926 an effort was made to lease the Maghrebi waqf, which included the wall, with the plan of eventually buying it.[68] Negotiations were begun in secret by the Jewish judge Gad Frumkin, with financial backing from American millionaire Nathan Straus.[68] The chairman of the Palestine Zionist Executive, Colonel F. H. Kisch, explained that the aim was "quietly to evacuate the Moroccan occupants of those houses which it would later be necessary to demolish" to create an open space with seats for aged worshippers to sit on.[68] However, Straus withdrew when the price became excessive and the plan came to nothing.[69] The Va'ad Leumi, against the advice of the Palestine Zionist Executive, demanded that the British expropriate the wall and give it to the Jews, but the British refused.[68]

In 1928 the World Zionist Organization reported that John Chancellor, High Commissioner of Palestine, believed that the Western Wall should come under Jewish control and wondered "why no great Jewish philanthropist had not bought it yet".[70]

September 1928 disturbances

In 1922, a Status Quo agreement issued by the mandatory authority forbade the placing of benches or chairs near the Wall. The last occurrence of such a ban was in 1915, but the Ottoman decree was soon retracted after intervention of the Chacham Bashi. In 1928 the District Commissioner of Jerusalem, Edward Keith-Roach, acceded to an Arab request to implement the ban. This led to a British officer being stationed at the Wall making sure that Jews were prevented from sitting. Nor were Jews permitted to separate the sexes with a screen. In practice, a flexible modus vivendi had emerged and such screens had been put up from time to time when large numbers of people gathered to pray.

On September 24, 1928, the Day of Atonement, British police resorted to removing by force a screen used to separate men and women at prayer. Women who tried to prevent the screen being dismantled were beaten by the police, who used pieces of the broken wooden frame as clubs. Chairs were then pulled out from under elderly worshipers. The episode made international news and Jews the world over objected to the British action. Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the Chief Rabbi of the ultraorthodox Jews in Jerusalem, issued a protest letter on behalf of his community, the Edah HaChareidis, and Agudas Yisroel strongly condemning the desecration of the holy site. Various communal leaders called for a general strike. A large rally was held in the Etz Chaim Yeshiva, following which an angry crowd attacked the local police station in which they believed Douglas Valder Duff, the British officer involved, was sheltering.[71]

Commissioner Edward Keith-Roach described the screen as violating the Ottoman status quo that forbade Jews from making any construction in the Western Wall area. He informed the Jewish community that the removal had been carried out under his orders after receiving a complaint from the Supreme Muslim Council. The Arabs were concerned that the Jews were trying to extend their rights at the wall and with this move, ultimately intended to take possession of the Masjid Al-Aqsa.[72] The British government issued an announcement explaining the incident and blaming the Jewish beadle at the Wall. It stressed that the removal of the screen was necessary, but expressed regret over the ensuing events.[71]

A widespread Arab campaign to protest against presumed Jewish intentions and designs to take possession of the Al Aqsa Mosque swept the country and a "Society for the Protection of the Muslim Holy Places" was established.[73] The Jewish National Council (Vaad Leumi) responding to these Arab fears declared in a statement that "We herewith declare emphatically and sincerely that no Jew has ever thought of encroaching upon the rights of Moslems over their own Holy places, but our Arab brethren should also recognise the rights of Jews in regard to the places in Palestine which are holy to them."[72] The committee also demanded that the British administration expropriate the wall for the Jews.[74]

From October 1928 onward, Mufti Amin al-Husayni organised a series of measures to demonstrate the Arabs' exclusive claims to the Temple Mount and its environs. He ordered new construction next to and above the Western Wall.[75] The British granted the Arabs permission to convert a building adjoining the Wall into a mosque and to add a minaret. A muezzin was appointed to perform the Islamic call to prayer and Sufi rites directly next to the Wall. These were seen as a provocation by the Jews who prayed at the Wall.[76][77] The Jews protested and tensions increased.

A British inquiry into the disturbances and investigation regarding the principal issue in the Western Wall dispute, namely the rights of the Jewish worshipers to bring appurtenances to the wall, was convened. The Supreme Muslim Council provided documents dating from the Turkish regime supporting their claims. However, repeated reminders to the Chief Rabbinate to verify which apparatus had been permitted failed to elicit any response. They refused to do so, arguing that Jews had the right to pray at the Wall without restrictions.[78] Subsequently, in November 1928, the Government issued a White Paper entitled "The Western or Wailing Wall in Jerusalem: Memorandum by the Secretary of State for the Colonies", which emphasised the maintenance of the status quo and instructed that Jews could only bring "those accessories which had been permitted in Turkish times."[79]

A few months later, Haj Amin complained to Chancellor that "Jews were bringing benches and tables in increased numbers to the wall and driving nails into the wall and hanging lamps on them."[80]

1929 Palestine riots

In the summer of 1929, the Mufti Haj Amin Al Husseinni ordered an opening be made at the southern end of the alleyway which straddled the Wall. The former cul-de-sac became a thoroughfare which led from the Temple Mount into the prayer area at the Wall. Mules were herded through the narrow alley, often dropping excrement. This, together with other construction projects in the vicinity, and restricted access to the Wall, resulted in Jewish protests to the British, who remained indifferent.[78]

On August 14, 1929, after attacks on individual Jews praying at the Wall, 6,000 Jews demonstrated in Tel Aviv, shouting "The Wall is ours." The next day, the Jewish fast of Tisha B'Av, 300 youths raised the Zionist flag and sang Hatikva at the Wall.[74] The day after, on August 16, an organized mob of 2,000 Muslim Arabs descended on the Western Wall, injuring the beadle and burning prayer books, liturgical fixtures and notes of supplication. The rioting spread to the Jewish commercial area of town, and was followed a few days later by the Hebron massacre.[81] One hundred and thirty-three Jews were killed and 339 injured in the Arab riots, and in the subsequent process of quelling the riots 110 Arabs were killed by British police. This was by far the deadliest attack on Jews during the period of British Rule over Palestine.

1930 international commission

In 1930, in response to the 1929 riots, the British Government appointed a commission "to determine the rights and claims of Muslims and Jews in connection with the Western or Wailing Wall", and to determine the causes of the violence and prevent it in the future. The League of Nations approved the commission on condition that the members were not British.

The Commission noted that "the Jews do not claim any proprietorship to the Wall or to the Pavement in front of it (concluding speech of Jewish Counsel, Minutes, page 908)."

The Commission concluded that the wall, and the adjacent pavement and Moroccan Quarter, were solely owned by the Muslim waqf. However, Jews had the right to "free access to the Western Wall for the purpose of devotions at all times", subject to some stipulations that limited which objects could be brought to the Wall and forbade the blowing of the shofar, which was made illegal. Muslims were forbidden to disrupt Jewish devotions by driving animals or other means.[4]

The recommendations of the Commission were brought into law by the Palestine (Western or Wailing Wall) Order in Council, 1931, which came into effect on June 8, 1931.[82] Persons violating the law were liable to a fine of 50 pounds or imprisonment up to 6 months, or both.[82]

During the 1930s, at the conclusion of Yom Kippur, young Jews persistently flouted the shofar ban each year and blew the shofar resulting in their arrest and prosecution. They were usually fined or sentenced to imprisonment for three to six months. The Shaw commission determined that the violence occurred due to "racial animosity on the part of the Arabs, consequent upon the disappointment of their political and national aspirations and fear for their economic future."

Jordanian rule (1948–67)

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War the Old City together with the Wall was controlled by Jordan. Article VIII of the 1949 Armistice Agreement called for a Special Committee to make arrangements for (amongst other things) "free access to the Holy Places and cultural institutions and use of the cemetery on the Mount of Olives".[83] The committee sat multiple times during 1949, but both sides made additional demands and at the same time the Palestine Conciliation Commission was pressing for the internationalization of Jerusalem against the wishes of both parties.[84] No agreement was ever reached, leading to recriminations in both directions. Neither Israeli Arabs nor Israeli Jews could visit their holy places in the Jordanian territories.[85][86] An exception was made for Christians to participate in Christmas ceremonies in Bethlehem.[86] Some sources claim Jews could only visit the wall if they traveled through Jordan (which was not an option for Israelis) and did not have an Israeli visa stamped in their passports.[87] Only Jordanian soldiers and tourists were to be found there. A vantage point on Mount Zion, from which the Wall could be viewed, became the place where Jews gathered to pray. For thousands of pilgrims, the mount, being the closest location to the Wall under Israeli control, became a substitute site for the traditional priestly blessing ceremony which takes place on the Three Pilgrimage Festivals.[88]

"Al Buraq (Wailing Wall) Rd" sign

During the Jordanian rule of the Old City, a ceramic street sign in Arabic and English was affixed to the stones of the ancient wall. Attached 2.1 metres (6.9 ft) up, it was made up of eight separate ceramic tiles and said Al Buraq Road in Arabic at the top with the English "Al-Buraq (Wailing Wall) Rd" below. When Israeli soldiers arrived at the wall in June 1967, one attempted to scrawl Hebrew lettering on it.[89] The Jerusalem Post reported that on June 8, Ben-Gurion went to the wall and "looked with distaste" at the road sign; "this is not right, it should come down" and he proceeded to dismantle it.[90] This act signaled the climax of the capture of the Old City and the ability of Jews to once again access their holiest sites.[91] Emotional recollections of this event are related by David Ben-Gurion and Shimon Peres.[92]

First years under Israeli rule (1967–69)

Declarations after the conquest

Following Israel's victory during the 1967 Six-Day War, the Western Wall came under Israeli control. Brigadier Rabbi Shlomo Goren proclaimed after its capture that "Israel would never again relinquish the Wall", a stance supported by Israeli Minister for Defence Moshe Dayan and Chief of Staff General Yitzhak Rabin.[93] Rabin described the moment Israeli soldiers reached the Wall:

"There was one moment in the Six-Day War which symbolized the great victory: that was the moment in which the first paratroopers—under Gur's command—reached the stones of the Western Wall, feeling the emotion of the place; there never was, and never will be, another moment like it. Nobody staged that moment. Nobody planned it in advance. Nobody prepared it and nobody was prepared for it; it was as if Providence had directed the whole thing: the paratroopers weeping—loudly and in pain—over their comrades who had fallen along the way, the words of the Kaddish prayer heard by Western Wall's stones after 19 years of silence, tears of mourning, shouts of joy, and the singing of "Hatikvah"".[94]

Demolition of the Moroccan Quarter

Forty-eight hours after capturing the wall, the military, without explicit government order,[95] hastily proceeded to demolish the entire Moroccan Quarter, which stood 4 metres (13 ft) from the Wall.[96] The Sheikh Eid Mosque, which was built over one of Jerusalem's oldest Islamic schools, the Afdiliyeh, named after one of Saladin's sons, was pulled down to make way for the plaza. It was one of three or four that survived from Saladin's time.[97] 106 Arab families consisting of 650 people were ordered to leave their homes at night. When they refused, bulldozers began to demolish the buildings with people still inside, killing one person and injuring a number of others.[98][99][100][101]

According to Eyal Weizman, Chaim Herzog, who later became Israel's sixth president, took much of the credit for the destruction of the neighbourhood:

When we visited the Wailing Wall we found a toilet attached to it ... we decided to remove it and from this we came to the conclusion that we could evacuate the entire area in front of the Wailing Wall ... a historical opportunity that will never return ... We knew that the following Saturday [sic Wednesday], June 14, would be the Jewish festival of Shavuot and that many will want to come to pray ... it all had to be completed by then.[102]

Historian Matthew Teller, who investigated the story of the toilet, judged it as improbable.[103]

The narrow pavement, which could accommodate a maximum of 12,000 per day, was transformed into an enormous plaza that could hold in excess of 400,000.[104] Several months later, the pavement close to the wall was excavated to a depth of two and half metres, exposing an additional two courses of large stones.[105]

A complex of buildings against the wall at the southern end of the plaza, that included Madrasa Fakhriya and the house that the Abu al-Sa'ud family had occupied since the 16th century, were spared in the 1967 destruction, but demolished in 1969.[106][107] The section of the wall dedicated to prayers was thus extended southwards to double its original length, from 28 to 60 metres (92 to 197 ft), while the 4 metres (13 ft) space facing the wall grew to 40 metres (130 ft).

The narrow, approximately 120 square metres (1,300 sq ft) pre-1948 alley along the wall, used for Jewish prayer, was enlarged to 2,400 square metres (26,000 sq ft), with the entire Western Wall Plaza covering 20,000 square metres (4.9 acres), stretching from the wall to the Jewish Quarter.[108]

Plaza

The new plaza created in 1967 is used for worship and public gatherings, including Bar mitzvah celebrations and the swearing-in ceremonies of newly full-fledged soldiers in the Israel Defense Forces. Tens of thousands of Jews flock to the wall on the Jewish holidays, and particularly on the fast of Tisha B'Av, which marks the destruction of the Temple and on Jerusalem Day, which commemorates the reunification of Jerusalem in 1967 and the delivery of the Wall into Jewish hands.

In November 2010, the government approved a NIS 85m ($23m) scheme to improve access from the Jewish Quarter and upgrade infrastructure at the Wall.[109]

Orthodox rules

Conflicts over prayer at the national monument began a little more than a year after Israel's victory in the Six-Day War, which again made the site accessible to Jews. In July 1968 the World Union for Progressive Judaism, which had planned the group's international convention in Jerusalem, appealed to the Knesset after the Ministry of Religious Affairs prohibited the organization from hosting mixed-gender services at the Wall. The Knesset committee on internal affairs backed the Ministry of Religious Affairs in disallowing the Jewish convention attendees, who had come from over 24 countries, from worshiping in their fashion. The Orthodox held that services at the Wall should follow traditional Jewish law for segregated seating followed in synagogues, while the non-Orthodox perspective was that "the Wall is a shrine of all Jews, not one particular branch of Judaism."[110]

Wilson's Arch area

Archaeology

Transformation into worship area

In September 1983, U.S. Sixth Fleet Chaplain, Rabbi Arnold Resnicoff was allowed to hold an unusual interfaith service—the first interfaith service ever conducted at the Wall during the time it was under Israeli control—that included men and women sitting together. The ten-minute service included the Priestly Blessing, recited by Resnicoff, who is a Kohen. A Ministry of Religions representative was present, responding to press queries that the service was authorized as part of a special welcome for the U.S. Sixth Fleet.[111][112][113]

In 2005, the Western Wall Heritage Foundation initiated a major renovation effort under Rabbi-of-the-Wall Shmuel Rabinovitch. Its goal was to renovate and restructure the area within Wilson's Arch, the covered area to the left of worshipers facing the Wall in the open prayer plaza, in order to increase access for visitors and for prayer.[114][115]

The restoration of the men's section included a Torah ark that can house over 100 Torah scrolls, in addition to new bookshelves, a library, heating for the winter, and air conditioning for the summer.[114] A new room was also built for the scribes who maintain and preserve the Torah scrolls used at the Wall.[114] New construction also included a women's section,[116] overlooking the men's prayer area, so that women could use this separate area to "take part in the services held inside under the Arch" for the first time.[117]

On July 25, 2010, a ner tamid, an oil-burning "eternal light," was installed within the prayer hall within Wilson's Arch, the first eternal light installed in the area of the Western Wall.[118] According to the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, requests had been made for many years that "an olive oil lamp be placed in the prayer hall of the Western Wall Plaza, as is the custom in Jewish synagogues, to represent the menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem as well as the continuously burning fire on the altar of burnt offerings in front of the Temple," especially in the closest place to those ancient flames.[118]

A number of special worship events have been held since the renovation. They have taken advantage of the cover, temperature control,[119] and enhanced security.[120]

Robinson's Arch area

Archaeology

At the southern end of the Western Wall, Robinson's Arch along with a row of vaults once supported stairs ascending from the street to the Temple Mount.[121][better source needed]

The so-called Isaiah Stone, located under Robinson's Arch, has a carved inscription in Hebrew with a partial and slightly faulty quote from (or paraphrase of) Isaiah 66:14: "And you will see and your heart will rejoice and their bones like an herb [will flourish]" (the correct line from Isaiah would read "...your bones".) This gave room to various interpretations, some speculating about it being written during a period of hope for Jews. Alternatively, it might be connected to nearby graves. The inscription has tentatively been dated to the 4th-8th century, some extending the possible timespan all the way to the 11th century.[122] [123]

Non-Orthodox worship area

Because it does not come under the direct control of the Rabbi of the Wall or the Ministry of Religious Affairs, the site has been opened to religious groups that hold worship services that would not be approved by the Rabbi of the Western Wall or the Ministry of Religious Affairs in the major men's and women's prayer areas against the Wall.[121][better source needed] The worship site was inaugurated in 2004 and has since hosted services by Reform and Conservative groups, as well as services by the Women of the Wall.[124] A platform has been added in 2013 in order to expand the prayer area.[125]

In Judaism

History as place of prayer

Jews were banned from Jerusalem by the Roman authorities after the Second Jewish revolt (2nd century CE) and, although there are intermittent accounts of limited 9th of Av services on the Temple Mount, no sources from before the 7th-century Islamic conquest attest to any other Jewish services allowed near the Mount and many report that none were permitted. Sources conflict with regard to the Mount's status under Islamic rule, but Karaite commentator Salmon ben Jeroham (c. 950 CE) reports that Jews were initially granted wide access to the Mount, then restricted to gathering near "one of its gates", then banned entirely before his own time.[126][127]

10th–12th centuries

However, a synagogue was apparently founded by the Western Wall (in the broader sense) shortly after the time of Salmon. The Scroll of Ahimaaz, a historical chronicle written in 1050 CE, describes:

Samuel his son arose to replace [Paltiel], and this great man filled his father's place [in c. 980 CE] ... [He] dedicated 20,000 golden drachmas to the One Who Dwells on High, to entreat the favor of the Rider of Clouds. These were alms for the poor...; oil for the synagogue in the western wall, for [the lamps on] its bema ...[128][129][130]

This account of Jewish prayer at the edge of the Mount in confirmed by Daniel ben Azariah, who writes (c. 1055 CE) that Jews were then permitted to "pray near the Mount's gates".[131] In 1099 CE the Crusader army captured Jerusalem, killing almost every Jew inside, and banned Jewish pilgrims from approaching the Mount. In his Scroll of Revelation (c. 1125 CE), Abraham bar Hiyya records that:[132]

... the Romans who destroyed the Temple in the days of the evil Titus, though they despoiled its sanctuary, never claimed any ownership of the holy Mount or any need to pray there. But ever since the evil Constantine converted to Christianity, they have begun to make these claims ... Since [1099 CE] the Christians have desecrated the Mount, made the citadel their church, brought their idols within it, and prevented Jews from praying there. Ever since those villains took over the Mount, no Jew has been allowed to enter it, and none are to be found in all Jerusalem.

In another reversal by c. 1167 CE, during the later Crusader period, the Western Wall was reopened to Jewish prayer. Benjamin of Tudela attests:

. . . and the Gate of Jehoshaphat, which faced the Temple in ancient times. There is the Templi Domini, which is the site of the Temple, and on it is a large and very beautiful dome built by Umar bin al-Khataab. Although they come to pray, the gentiles do not bring any images or effigies onto the site. And in front of this place is the western wall, which was one of the walls in[a] the Holy of Holies; this is called the Gate of Mercy[b] and hither come all the Jews to pray before the wall in the courtyard[c].[134]

17th century

In 1625, David Finzi reported to the Jewish leadership of Carpi that:[47]

. . . from there we went up to the Temple Mount, passing mundane structures until we reached the peak of the Mount, where once the Temple stood, which was destroyed for our sins. Now a mosque is built upon it, and Jews are prohibited from entering it; only outside it, near the Western Wall, are Jews allowed to gather, and even this only in peaceful times—in difficult times, such as these, the Jewish community has decreed that no one go there. But in the first week of our visit, before this decree, we went all the way in, and kissed it, and I prostrated myself before its base, and there I said the ordered prayers, and also entreated God to bless all the Jews of Carpi ... Though it is called the Western Wall, nothing of the Temple whatever survived the destruction, the looting by thieves, and the construction of the mosque. They built a citadel on the site of the Foundation Stone, surpassingly lovely ...

Tensions eventually calmed again. Gedaliah of Siemiatycze, who lived in Jerusalem from 1700 to 1706, records that:[48]

Only Muslims are permitted to enter the Mount and not Jews or other peoples, unless they convert to the Muslim faith. They say that not just any faith is worthy of the Mount, and they continually remind us that the Muslims have superseded the Jews in the eyes of God. When we go to pray at the Wall, we press right up against it, like the lover in Song of Songs who "standeth behind our wall". On the eve of the New Moon, on Tisha ba'Av, and on other fast days, we go there to pray, and the women to raise their plangent cries, but no one challenges us, and even the qadi who lives there does not object. Though the Arab youths sometimes come to prey on us, they are easily bribed to leave us alone, and if caught by their own elders they are rebuked ... Prayer by the Wall usually meets with God's favor ... . Once in olden times, or so I heard, there was a terrible drought. The Jews declared a day of fasting, and they went with a Torah scroll to the Western Wall to pray, and God answered their prayers so readily that they had to wrap the scroll in their clothes on their return to the synagogue. Every Sabbath morning, after the services at the synagogue, we immediately set off for the Western Wall ... every single one of us, Ashkenazic and Sephardic, old and young ... there we recite those Psalms that mention Jerusalem, and Pitom haQtores, and Aleinu l'Shabeach, and the Kaddish, and we bless those in the diaspora who fundraise for Eretz Yisrael ... .

18th–19th centuries

| "On Friday afternoon, March 13, 1863, the writer visited this sacred spot. Here he found between one and two hundred Jews of both sexes and of all ages, standing or sitting, and bowing as they read, chanted and recited, moving themselves backward and forward, the tears rolling down many a face; they kissed the walls and wrote sentences in Hebrew upon them... The lamentation which is most commonly used is from Psalm 79:1 "O God, the heathen are come into Thy inheritance; Thy holy temple have they defiled."

(Rev. James W. Lee, 1863)[135] |

The writings of various travellers in the Holy Land, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, tell of how the Wall and its environs continued to be a place of devotion for the Jews.[4] Isaac Yahuda, a prominent member of the Sephardic community in Jerusalem recalled how men and women used to gather in a circle at the Wall to hear sermons delivered in Ladino. His great-grandmother, who arrived in Palestine in 1841, "used to go to the Western Wall every Friday afternoon, winter and summer, and stay there until candle-lighting time, reading the entire Book of Psalms and the Song of Songs...she would sit there by herself for hours."[136]

20th–21st centuries

In the past[dubious – discuss] women could be found sitting at the entrance to the Wall every Sabbath holding fragrant herbs and spices in order to enable worshipers to make additional blessings. In the hot weather they would provide cool water. The women also used to cast lots for the privilege of sweeping and washing the alleyway at the foot of the Wall.[53]

Throughout several centuries, the Wall is where Jews have gathered to express gratitude to God or to pray for divine mercy. On news of the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 thousands of Jews went to the Wall to offer prayers for the "success of His Majesty's and Allied Forces in the liberation of all enemy-occupied territory."[137] On October 13, 1994, 50,000 gathered to pray for the safe return of kidnapped soldier Nachshon Wachsman.[138] August 10, 2005 saw a massive prayer rally at the Wall. Estimates of people protesting Israel's unilateral disengagement plan ranged from 50,000 to 250,000 people.[citation needed][139] Every year on Tisha B'Av large crowds congregate at the Wall to commemorate the destruction of the Temple. In 2007 over 100,000 gathered.[140] During the month of Tishrei 2009, a record 1.5 million people visited the site.[141]

Relation to the Foundation Stone

In Judaism, the Western Wall is venerated as the sole remnant of the Holy Temple. It has become a place of pilgrimage for Jews, as it is the closest permitted accessible site to the holiest spot in Judaism, namely the Even ha-shetiya or Foundation Stone, which lies on the Temple Mount. According to one rabbinic opinion, Jews may not set foot upon the Temple Mount and doing so is a sin punishable by Kareth. While almost all historians and archaeologists and some rabbinical authorities believe that the rocky outcrop in the Dome of the Rock is the Foundation Stone,[142] some rabbis say it is located directly opposite the exposed section of the Western Wall, near the El-kas fountain.[143] This spot was the site of the Holy of Holies when the Temple stood.

Part of the Temple proper

Rabbinic tradition teaches that the western wall was built upon foundations laid by the biblical King Solomon from the time of the First Temple.[144]

Some medieval rabbis claimed that today's Western Wall is a surviving wall of the Temple itself and cautioned Jews from approaching it, lest they enter the Temple precincts in a state of impurity.[145] Many contemporary rabbis believe that the rabbinic traditions were made in reference to the Temple Mount's Western Wall, which accordingly endows the Wall with inherent holiness.[146]

Divine custody

A 7th-century Midrash refers to a western wall of the Temple which "would never be destroyed",[10] and a 6th-century Midrash mentions how Rome was unable to topple the western wall due to the Divine oath promising its eternal survival.[147]

Divine Presence

An 11th-century Midrash quotes a 4th-century scholar: "Rav Acha said that the Divine Presence has never departed from the Western Wall",[148] and the Zohar (13th century) similarly writes that "the Divine Presence rests upon the Western Wall".[149]

Eighteenth-century scholar Jonathan Eybeschutz writes that "after the destruction of the Temple, God removed His Presence from His sanctuary and placed it upon the Western Wall where it remains in its holiness and honour".[150] It is told that great Jewish sages, including Isaac Luria and the Radvaz, experienced a revelation of the Divine Presence at the wall.[151]

Kabbalah of the word kotel

Rabbi Zvi Hirsch Kaindenover discusses the mystical aspect of the Hebrew word kotel when discussing the significance of praying against a wall. He cites the Zohar which writes that the word kotel, meaning wall, is made up of two parts: "Ko", which has the numerical value of God's name, and "Tel", meaning mount, which refers to the Temple and its Western Wall.[152]

Ritual

Status as a synagogue

Many contemporary Orthodox scholars rule that the area in front of the Wall has the status of a synagogue and must be treated with due respect.[144] This is the view upheld by the authority in charge of the wall. As such, men and married women are expected to cover their heads upon approaching the Wall, and to dress appropriately. When departing, the custom is to walk backwards away from the Wall to show its sanctity.[144] On Saturdays, it is forbidden to enter the area with electronic devices, including cameras, which infringe on the sanctity of the Sabbath.

Contact with the Wall

Some Orthodox Jewish codifiers warn against inserting fingers into the cracks of the Wall as they believe that the breadth of the Wall constitutes part of the Temple Mount itself and retains holiness, while others who permit doing so claim that the Wall is located outside the Temple area.[153][non-primary source needed]

In the past, some visitors would write their names on the Wall, or based upon various scriptural verses, would drive nails into the crevices. These practices stopped after rabbis determined that such actions compromised the sanctity of the Wall.[53] Another practice also existed whereby pilgrims or those intending to travel abroad would hack off a chip from the Wall or take some of the sand from between its cracks as a good luck charm or memento. In the late 19th century the question was raised as to whether this was permitted and a long responsa appeared in the Jerusalem newspaper Havatzelet in 1898. It concluded that even if according to Jewish Law it was permitted, the practices should be stopped as it constituted a desecration.[53] More recently the Yalkut Yosef rules that it is forbidden to remove small chips of stone or dust from the Wall, although it is permissible to take twigs from the vegetation which grows in the Wall for an amulet, as they contain no holiness.[154] Cleaning the stones is also problematic from a halachic point of view. Blasphemous graffiti once sprayed by a tourist was left visible for months until it began to peel away.[155]

Barefoot approach

There was once an old custom of removing one's shoes upon approaching the Wall. A 17th-century collection of special prayers to be said at holy places mentions that "upon coming to the Western Wall one should remove his shoes, bow and recite...".[53] Rabbi Moses Reicher wrote[year needed] that "it is a good and praiseworthy custom to approach the Western Wall in white garments after ablution, kneel and prostrate oneself in submission and recite "This is nothing other than the House of God and here is the gate of Heaven." When within four cubits of the Wall, one should remove their footwear."[53] Over the years the custom of standing barefoot at the Wall has ceased, as there is no need to remove one's shoes when standing by the Wall, because the plaza area is outside the sanctified precinct of the Temple Mount.[154]

Mourning over the Temple's destruction

According to Jewish Law, one is obliged to grieve and rend one's garment upon visiting the Western Wall and seeing the desolate site of the Temple.[156] Bach (17th century) instructs that "when one sees the Gates of Mercy which are situated in the Western Wall, which is the wall King David built, he should recite: Her gates are sunk into the ground; he hath destroyed and broken her bars: her king and her princes are among the nations: the law is no more; her prophets also find no vision from the Lord".[157] Some scholars write that rending one's garments is not applicable nowadays as Jerusalem is under Jewish control. Others disagree, pointing to the fact that the Temple Mount is controlled by the Muslim waqf and that the mosques which sit upon the Temple site should increase feelings of distress. If one hasn't seen the Wall for over 30 days, the prevailing custom is to rend one's garments, but this can be avoided if one visits on the Sabbath or on festivals.[158] According to Donneal Epstein, a person who has not seen the Wall within the last 30 days should recite: "Our Holy Temple, which was our glory, in which our forefathers praised You, was burned and all of our delights were destroyed".[159]

Significance as place of prayer

The Sages of the Talmud stated that anyone who prays at the Temple in Jerusalem, "it is as if he has prayed before the throne of glory because the gate of heaven is situated there and it is open to hear prayer."[160] Jewish Law stipulates that the Silent Prayer should be recited facing towards Jerusalem, the Temple and ultimately the Holy of Holies,[161] as God's bounty and blessing emanates from that spot.[144] It is generally believed that prayer by the Western Wall is particularly beneficial since it was that wall which was situated closest to the Holy of Holies.[144] Rabbi Jacob Ettlinger (1798–1871) writes, making reference to a medieval rabbi, "since the Theology and ritual Israel's prayers ascend on high there... as one of the great ancient kabbalists Rabbi Joseph Gikatilla said, when the Jews send their prayers from the Diaspora in the direction of Jerusalem, from there they ascend by way of the Western Wall."[53] A well-known segula (efficacious remedy) for finding one's soulmate is to pray for 40 consecutive days at the Western Wall,[162] a practice apparently conceived by Rabbi Yisroel Yaakov Fisher (1928–2003).[163]

Egalitarian and non-Orthodox prayer

While during the late 19th century, no formal segregation of men and women was to be found at the Wall,[164] conflict erupted in July 1968 when members of the World Union for Progressive Judaism were denied the right to host a mixed-gender service at the site after the Ministry of Religious Affairs insisted on maintaining the gender segregation customary at Orthodox places of worship. The progressives responded by claiming that "the Wall is a shrine of all Jews, not one particular branch of Judaism."[110]

In 1988, the small but vocal group called Women of the Wall launched a campaign for recognition of non-Orthodox prayer at the Wall.[165][166] Their form and manner of prayer elicited a violent response from some Orthodox worshippers and they were subsequently banned from holding services at the site.[124] After repeated attacks by haredim, in 1989 the Women of the Wall petitioned to secure the right of women to pray at the wall without restrictions.[167]

A decade on, some commentators called for the closure of the Wall unless an acceptable solution to the controversy was found.[168]

In 2003 Israel's Supreme Court upheld the ban on non-Orthodox worship at the Wall,[121][better source needed] disallowing any women from reading publicly from the Torah or wearing traditional prayer shawls at the plaza itself, but instructed the Israeli government to prepare the site of Robinson's Arch to host such events,[167] given that this area does not come under the direct control of the Rabbi of the Wall or the Ministry of Religious Affairs.[121][better source needed] The government responded by allocating Robinson's Arch for such purposes.[167]

The Robinson's Arch worship site was inaugurated in August 2004 and has since hosted services by Reform and Conservative groups, as well as services by the Women of the Wall.[124]

In 2012, critics still complained about the restrictions at the Western Wall, saying Israel had "turned a national monument into an ultra-Orthodox synagogue."[169]

In April 2013 things came to a head. In response to the repeated arrest of women, including Anat Hoffman, found flouting the law, the Jewish Agency observed 'the urgent need to reach a permanent solution and make the Western Wall once again a symbol of unity among the Jewish people, and not one of discord and strife."[124] Jewish Agency leader Natan Sharansky spearheaded a concept that would expand and renovate the Robinson's Arch area into an area where people may "perform worship rituals not based on the Orthodox interpretation of Jewish tradition."[170] The Jerusalem District Court ruled that as long as there was no other appropriate area for pluralistic prayer, prayer according to non-Orthodox custom should be allowed at the Wall,[171] and a judge ruled that the 2003 Israeli Supreme Court ruling prohibiting women from carrying a Torah or wearing prayer shawls had been misinterpreted and that Women of the Wall prayer gatherings at the Wall should not be deemed as disturbing the public order.[124]

On August 25, 2013, a new 4,480 square foot prayer platform named "Ezrat Yisrael Plaza" was completed as part of this plan of facilitating non-Orthodox worship, with access to the platform at all hours, even when the rest of the area's archaeological park is closed to visitors.[125][172] After some controversy regarding the question of authority over this prayer area, the announcement was made that it would come under the authority of a future government-appointed "pluralist council" that would include non-Orthodox representatives.[173]

In January 2016, the Israeli Cabinet approved a plan to designate a new space at the Kotel that would be available for egalitarian prayer and that would not be controlled by the Rabbinate. Women of the Wall welcomed the decision,[174] although Sephardic Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar of Jerusalem said creating a mixed-gender prayer section was paramount to destroying the Wall. The Chief Rabbinate said it would create an alternate plan.[175] In June 2017, it was announced that the plan approved in January 2016 had been suspended.[176][177]

Prayer notes

There is a much publicised practice of placing slips of paper containing written prayers into the crevices of the Wall. The earliest account of this practice describes Chaim ibn Attar (d. 1743) writing an amulet for a petitioner and instructing him to place it inside the wall.[178] More than a million notes are placed each year[179] and the opportunity to e-mail notes is offered by a number of organisations.[180] It has become customary for visiting dignitaries to place notes too.[181][182]

Chabad tefillin stand

Shortly after the Western Wall came under Israeli control in 1967, a stand of the Chabad movement offering phylacteries (tefillin) was erected with permission from Rabbi Yehuda Meir Getz, the first rabbi of the Kotel. The stand offers male visitors the chance to put on tefillin, a daily Jewish prayer ritual. In the months following the Six-Day War an estimated 400,000 Jews observed this ritual at the stand.[183] The stand is staffed by multilingual Chabad volunteers and an estimated 100,000 male visitors put on tefillin there annually.[184][better source needed]

In Islam

Tradition of the place of tethering

Muslim reverence for the site is derived from the belief that the Islamic prophet Muhammad tied his winged mount Buraq nearby during his night journey to Jerusalem. Various places have been suggested for the exact spot where Buraq was tethered, but for several centuries the preferred location has been the al-Buraq Mosque, which is just inside the wall at the south end of the present Western Wall plaza. The mosque is located above an ancient passageway, which once came out through the long-sealed Barclay's Gate whose huge lintel is still visible directly below the Maghrebi Gate.[185]

There are four different locations, along the southern, eastern, and western wall, with gates known successively or simultaneously as the Gate of the Prophet and al-Buraq.[44]

Early Muslim vs. Mamluk-period traditions

US scholar Charles D. Matthews wrote in 1932 that, based on the work of Muslim authors of the 10th to 11th centuries (the later part of the Early Muslim period), the place where Prophet Muhammad had tethered Buraq and entered the haram was considered at the time to be the Double Gate of the Temple Mount's southern wall.[44] To reach this conclusion, which he shares with Charles Wilson and Guy Le Strange, he analysed the relevant texts by Ibn al-Faqih (903), Ibn Abd Rabbih (913), and mainly by Muqaddasi (985) and Nasir-i-Khusrau (1047).[44] One of the earliest authors who are more ambiguous, opening the possibility of identifying the Gate of the Prophet and al-Buraq with either the Double or Barclay's Gate, is Burhan ad-Din ibn al-Firkah of Damascus (d. 1329).[44] Another Mamluk-period writer, Mujir ad-Din (1496), is the first one to unambiguously identify Barclay's Gate as the Gate of al-Buraq or of the Prophet.[44] However, Mujir ad-Din's work is effectively a rework of earlier texts, with as-Suyuti (1471) being the main source—and he fails to mention that as—Suyuti stated that the Gate of the Inspector, located close to the northern end of the western wall, was also known as the Gate of al-Buraq or of the Prophet.[44]

Ottoman-period identification

To the previously mentioned variations in identification adds yet another gate, the now walled-up Funeral Gate (bab al-jana'iz), just south of the Golden Gate, also known as 'Gate of al-Buraq' and marked as such on a 1864 Temple Mount map by Melchior de Vogüé, based on the 1833 survey by Frederick Catherwood[44][186] (see Bab al-Rahmah Cemetery at MadainProject.com for a photo and short description).

When a British Jew asked the Egyptian authorities in 1840 for permission to re-pave the ground in front of the Western Wall, the governor of Syria wrote:

- It is evident from the copy of the record of the deliberations of the Consultative Council in Jerusalem that the place the Jews asked for permission to pave adjoins the wall of the Haram al-Sharif and also the spot where al-Buraq was tethered, and is included in the endowment charter of Abu Madyan, may God bless his memory; that the Jews never carried out any repairs in that place in the past. ... Therefore the Jews must not be enabled to pave the place.[187]

Carl Sandreczki, who was charged with compiling a list of place names for Charles Wilson's Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem in 1865, reported that the street leading to the Western Wall, including the part alongside the wall, belonged to the Hosh (court/enclosure) of al Burâk, "not Obrâk, nor Obrat".[188] In 1866, the Prussian Consul and Orientalist Georg Rosen wrote that "The Arabs call Obrâk the entire length of the wall at the wailing place of the Jews, southwards down to the house of Abu Su'ud and northwards up to the substructure of the Mechkemeh [Shariah court]. Obrâk is not, as was formerly claimed, a corruption of the word Ibri (Hebrews), but simply the neo-Arabic pronunciation of Bōrâk, ... which, whilst (Muhammad) was at prayer at the holy rock, is said to have been tethered by him inside the wall location mentioned above."[15]

The name Hosh al Buraq appeared on the maps of Wilson's 1865 survey, its revised editions of 1876 and 1900, and other maps in the early 20th century.[189]

British Mandate

In 1922, Hosh al Buraq was the street name specified by the official Pro-Jerusalem Council.[190]

In Christianity

Some scholars[who?] believe that when Jerusalem came under Christian rule in the 4th century, there was a purposeful "transference" of respect for the Temple Mount and the Western Wall in terms of sanctity to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, while the sites around the Temple Mount became a refuse dump for Christians.[191] However, the actions of many modern Christian leaders, including Pope John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI, who visited the Wall and left prayer messages in its crevices, have symbolized for many Christians a restoration of respect and even veneration for this ancient religious site.[191]

Ideological views

Jewish

Most Jews, religious and secular, consider the wall to be important to the Jewish people since it was originally built to hold the Second Temple. They consider the capture of the wall by Israel in 1967 as a historic event since it restored Jewish access to the site after a 19-year gap.[192]

Israeli philosopher Yeshayahu Leibowitz referred to the attitude towards the Western Wall as "idolatry"[193] and publicly decried the Israelis' triumphalism following the 1967 victory.[194]

Dan Bahat, former district archaeologist of Jerusalem who headed the Western Wall Tunnel excavations in the years 1986–2007, decried in 2018 the transformation of this iconic historical site into a regulated place of worship: "The Western Wall is sacrosanct. But out of a national monument, it has become a synagogue."[195]

Israeli

A poll carried out in 2007 by the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies indicated that 96% of Israeli Jews were against Israel relinquishing the Western Wall.[196]

Yitzhak Reiter writes that "the Islamization and de-Judaization of the Western Wall are a recurrent motif in publications and public statements by the heads of the Islamic Movement in Israel."[197]

Muslim

In December 1973, King Faisal of Saudi Arabia stated that "Only Muslims and Christians have holy places and rights in Jerusalem". The Jews, he maintained, had no rights there at all. As for the Western Wall, he said, "Another wall can be built for them. They can pray against that".[198]

Palestinian

The Palestinian National Authority's State Information Service (SIS) stated as fact that the Jews did not consider the Wall as a place for worship until after the Balfour Declaration was issued in 1917.[199]

In 2006, Dr. Hassan Khader, founder of the Al Quds Encyclopedia, told PA television that the first connection of the Jews to the Wall is "a recent one, which began in the 16th century...not ancient...like the roots of the Islamic connection".[200]

The Mufti of Jerusalem, Sheikh Ekrima Sa'id Sabri said in 2007 that "there never was a Jewish temple on the Temple Mount" and that "there is not a single stone with any relation at all to the history of the Hebrews."[201]

In November 2010, an official paper published by the PA Ministry of Information denied Jewish rights to the Wall. It stated that "Al-Buraq Wall is in fact the western wall of Al-Aksa Mosque" and that Jews had only started using the site for worship after the 1917 Balfour Declaration.[202]

American

While recognizing the difficulties inherent in any ultimate peace agreement that involves the status of Jerusalem, the official position of the United States includes a recognition of the importance of the Wall to the Jewish people, and has condemned statements that seek to "delegitimize" the relationship between Jews and the area in general, and the Western Wall in particular. For example, in November 2010, the Obama administration "strongly condemned a Palestinian official's claim that the Western Wall in the Old City has no religious significance for Jews and is actually Muslim property." The U.S. State Department noted that the United States rejects such a claim as "factually incorrect, insensitive and highly provocative."[203]

Administration

After the 1967 Arab–Israeli war, Rabbi Yehuda Meir Getz was named the overseer of proceedings at the wall.[204] After Rabbi Getz's death in 1995, Rabbi Shmuel Rabinowitz was given the position.[205] The Western Wall Heritage Foundation is the administrative body put in charge of the Wall.

See also

- List of artifacts in biblical archaeology

- Mughrabi Bridge

- Pro–Wailing Wall Committee

- Southern Wall

- Walls of Jerusalem

- Western Stone

- Western Wall camera

- Western Wall Tunnel

Footnotes

- ^ The exact meaning of this phrase (אחד מן הכתלים שהיו [נ"א +במקדש] בקדש הקדשים which was one of the walls [1 MS: +in the Temple] in the holy of holies) is obscure, confused by the preposition ב in. Most translators emend to "of the Holy of Holies," but Yisrael Ariel argues that the meaning of Qodesh haqQodashim (lit. 'Holy of Holies') had expanded to include a larger portion of the site, just as had those of haBayyit hagGadol (lit. 'the Great House') and haAzarah (lit. 'the court', but see following note).

- ^ Today "Gate of Mercy" refers to a literal gate on the eastern side of the platform. According to Samuel Rabinowitz (2012), The Western Wall [in Hebrew], p. 262, Benjamin intends "gate of mercy" as a term of art meaning "place where prayer is received favorably" (cf. Talmudic idiom "he knocked on the gates of mercy" viz. "he prayed"); others, however, assume the reverse: that the Gate of Mercy was once known as the "western wall".

- ^ The term azara in its technical sense refers only to the inner court of the Temple, including the central building and the altars. However, Benjamin's contemporaries used it loosely to refer to a different part of, or even the whole of, the Temple site. See Yisrael Ariel, "Prayer on the Temple Mount" (1995) [in Hebrew] in Memorial Volume for Rabbi Shlomo Goren, ed. Yitzhak Alfasi, p. 268. Similarly, Al-Biruni (c. 1000 CE) refers to a ritual on Simchat Torah in which the Jews would "assemble in the harhara of Jerusalem" for a procession (The Chronology of Ancient Nations, ed. Eduard Sachau (1879), p. 270), and one Cairo Geniza letter refers to "Rabbi Musa who was killed in the azara by the Ananites" (JQR V p. 554).

- ^ Hebrew: , translit.: HaKotel HaMa'aravi; Ashkenazic pronunciation: HaKosel HaMa'arovi

- ^ "The Temple Mount in the Herodian Period (37 BC–70 AD)". Biblical Archaeology Society. July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2020.

- ^ Ramon, Amnon (2002). "Delicate balances at the Temple Mount, 1967–1999". In Marshall J. Breger; Ora Ahimeir (eds.). Jerusalem: A City and Its Future. Syracuse University Press for the Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. p. 300. ISBN 978-0815629139. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Löfgren, Eliel; Barde, Charles; Van Kempen, J. (December 1930). Report of the Commission appointed by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, with the approval of the Council of the League of Nations, to determine the rights and claims of Moslems and Jews in connection with the Western or Wailing Wall at Jerusalem (UNISPAL doc A/7057-S/8427, February 23, 1968)

- ^ a b c d e Halkin 2001

- ^ UN Conciliation Commission (1949). United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine Working Paper on the Holy Places. p. 26.