Trans–New Guinea languages

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2008) |

| Trans–New Guinea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | New Guinea, Nusa Tenggara, Maluku Islands | |||

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families | |||

| Subdivisions |

| |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-5 | ngf | |||

| Glottolog | None nucl1709 (Nuclear Trans–New Guinea) | |||

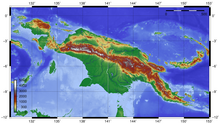

The extent of various proposals for Trans–New Guinea.

Core TNG: Families accepted by Glottolog[1]

Other Trans–New Guinea families proposed by Ross (2005)

Other Papuan languages

Austronesian languages

Uninhabited | ||||

The various families constituting Ross' conception of Trans–New Guinea. The greatest TNG diversity is in the eastern highlands. (After Ross 2005.)

| ||||

Trans–New Guinea (TNG) is an extensive family of Papuan languages spoken in New Guinea and neighboring islands, perhaps the third-largest language family in the world by number of languages. The core of the family is considered to be established, but its boundaries and overall membership are uncertain. There have been three main proposals.

History of the proposal

Although Papuan languages for the most part are poorly documented, several of the branches of Trans–New Guinea have been recognized for some time. The Eleman languages were first proposed by S. Ray in 1907, parts of Marind were recognized by Ray and JHP Murray in 1918, and the Rai Coast languages in 1919, again by Ray.

The precursor of the Trans–New Guinea family was Stephen Wurm's 1960 proposal of an East New Guinea Highlands family. Although broken up as a unit (though retained within TNG) by Malcolm Ross in 2005, it united different branches of TNG for the first time, linking Engan, Chimbu–Wahgi, Goroka, and Kainantu. (Duna and Kalam were added in 1971.) Then in 1970 Clemens Voorhoeve and Kenneth McElhanon noted 91 lexical resemblances between the Central and South New Guinea (CSNG) and Finisterre–Huon families, which they had respectively established a few years earlier. Although they did not work out regular sound correspondences, and so could not distinguish between cognates due to genealogical relationship, cognates due to borrowing, and chance resemblances, their research was taken seriously. They chose the name Trans–New Guinea because this new family was the first to span New Guinea, from the Bomberai Peninsula of western West Irian to the Huon Peninsula of eastern PNG. They also noted possible cognates in other families Wurm would later add to TNG: Wurm's East New Guinea Highlands, Binandere in the 'Bird's Tail' of PNG, and two families that John Z'graggen would later (1971, 1975) unite in his 100-language Madang–Adelbert Range family.

In 1975 Wurm accepted Voorhoeve and McElhanon's suspicions about further connections, as well as Z'graggen's work, and postualed additional links to, among others, the languages of the island of Timor to the west of New Guinea, Angan, Goilalan, Koiarian, Dagan, Eleman, Wissel Lakes, the erstwhile Dani-Kwerba family, and the erstwhile Trans-Fly–Bulaka River family (which he had established in 1970), expanding TNG into an enormous language phylum that covered most of the island of New Guinea, as well as Timor and neighboring islands, and included over 500 languages spoken by some 2 300 000 people. However, part of the evidence for this was typological, and Wurm stated that he did not expect it to stand up well to scrutiny. Although he based the phylum on characteristic personal pronouns, several of the branches had no pronouns in common with the rest of the family, or even had pronouns related to non-TNG families, but were included because they were grammatically similar to TNG. Other families that had typical TNG pronouns were excluded because they did not resemble other TNG families in their grammatical structure.

Because grammatical typology is readily borrowed—many of the Austronesian languages in New Guinea have grammatical structures similar to their Papuan neighbors, for example, and conversely many Papuan languages resemble typical Austronesian languages typologically—other linguists were skeptical. William A. Foley rejected Wurm's and even some of Voorhoeve's results, and broke much of TNG into its constituent parts: several dozen small but clearly valid families, plus a number of apparent isolates.

In 2005 Malcolm Ross published a draft proposal re-evaluating Trans–New Guinea, and found what he believed to be overwhelming evidence for a reduced version of the phylum, based solely on lexical resemblances, which retained as much as 85% of Wurm's hypothesis, though some of it tentatively.

The strongest lexical evidence for any language family is shared morphological paradigms, especially highly irregular or suppletive paradigms with bound morphology, because these are extremely resistant to borrowing. For example, if the only recorded German words were gut "good" and besser "better", that alone would be enough to demonstrate that in all probability German was related to English. However, because of the great morphological complexity of many Papuan languages, and the poor state of documentation of nearly all, in New Guinea this approach is essentially restricted to comparing pronouns. Ross reconstructed pronouns sets for Foley's basic families and compared these reconstructions, rather than using a direct mass comparison of all Papuan languages; attempted to then reconstruct the ancestral pronouns of the proto-Trans–New Guinea language, such as *ni "we", *ŋgi "you", *i "they"; and then compared poorly supported branches directly to this reconstruction. Families required two apparent cognates to be included. However, if any language in a family was a match, the family was considered a match, greatly increasing the likelihood of coincidental resemblances, and because the plural forms are related to the singular forms, a match of 1sg and 1pl, although satisfying Ross's requirement of two matches, is not actually two independent matches, again increasing the likelihood of spurious matches. In addition, Ross counted forms like *a as a match to 2sg *ga, so that /ɡV, kV, ŋɡV, V/ all counted as matches to *ga. And although /n/ and /ɡ/ occur in Papuan pronouns at twice the level expected by their occurrence in pronouns elsewhere in the world, they do not correlate with each other as they would if they reflected a language family. That is, it is argued that Ross's pronouns do not support the validity of Trans–New Guinea, and do not reveal which families might belong to it.[3]

Ross also included in his proposal several better-attested families for non-pronominal evidence, despite a lack of pronouns common to other branches of TNG, and he suggested that there may be other families that would have been included if they had been better attested. Several additional families are only tentatively linked to TNG. Note also that because the boundaries of Ross's proposal are based primarily on a single parameter, the pronouns, all internal structure remains tentative.

The languages

Most TNG languages are spoken by only a few thousand people, with only four (Melpa, Enga, Western Dani, and Ekari) being spoken by more than 100,000. The most populous language outside of mainland New Guinea is Makasai on Timor, with 70,000.

The greatest linguistic diversity in Ross's Trans–New Guinea proposal, and therefore perhaps the location of the proto-Trans–New Guinea homeland, is in the interior highlands of Papua New Guinea, in the central-to-eastern New Guinea cordillera where Wurm first posited his East New Guinea Highlands family. Indonesian Papua and the Papuan Peninsula of Papua New Guinea (the "bird's tail") have fewer and more widely extended branches of TNG, and were therefore likely settled by TNG speakers after the protolanguage broke up. Ross speculates that the TNG family may have spread with the high population densities that resulted from the domestication of taro, settling quickly in the highland valleys along the length of the cordillera but spreading much more slowly into the malarial lowlands, and not at all into areas such as the Sepik River valley where the people already had yam agriculture and thus supported high population densities. Ross suggests that TNG may have arrived at its western limit, the islands near Timor, perhaps four to 4.5 thousand years ago, before the expansion of Austronesian into this area.

Classification

Wurm

An updated version of Wurm's 1975 classification can be found at MultiTree and in modified form at Ethnologue 15 (largely abandoned by Ethnologue 16). Wurm identifies the subdivisions of his Papuan classification as families (on the order of relatedness of the Germanic languages), stocks (on the order of the Indo-European languages), and phyla (on the order of the Afroasiatic languages). Trans–New Guinea is a phylum in this terminology. A language that is not related to any other at a family level or below is called a Trans–New Guinea isolate in this scheme.

Foley

As of 2003, William A. Foley accepted the core of TNG: "The fact, for example, that a great swath of languages in New Guinea from the Huon Peninsula to the highlands of Irian Jaya mark the object of a transitive verb with a set of verbal prefixes, a first person singular in /n/ and second person singular in a velar stop, is overwhelming evidence that these languages are all genetically related; the likelihood of such a system being borrowed vanishingly small."[4] He considered the relationship between the Finisterre–Huon, Eastern Highlands (Kainantu–Gorokan), and Irian Highlands (Dani – Paniai Lakes) families (and presumably some other smaller ones) to be established, and said that it is "highly likely" that the Madang family belongs as well. He considered it possible but not yet demonstrated that the Enga, Chimbu, Binandere, Angan, Ok, Awyu, Asmat (perhaps closest to Ok and Awyu), Mek, and the small language families of the tail of Papua New Guinea (Koiarian, Goilalan, etc., which he maintains have not been shown to be closely related to each other) may belong to TNG as well.

Ross

Ross does not use specialized terms for different levels of classification as Laycock and Wurm did. In the list given here, the uncontroversial families that are accepted by Foley and other Papuanists and that are the building blocks of Ross's TNG are printed in boldface. Language isolates are printed in italics.

Ross removed about 100 languages from Wurm's proposal, and only tentatively retained a few dozen more, but in one instance he added a language, the erstwhile isolate Porome.

Ross did not have sufficient evidence to classify all Papuan groups.

- Trans–New Guinea phylum (Ross 2005)

- West Trans–New Guinea linkage ? [a suspected old dialect continuum]

- West Bomberai – Timor–Alor–Pantar

- Timor–Alor–Pantar families (22)

- West Bomberai family (2)

- Paniai Lakes (Wissel Lakes) family (5)

- Dani family (13)

- West Bomberai – Timor–Alor–Pantar

- South Bird's Head (South Doberai) family (12)

- Tanah Merah (Sumeri) isolate

- Mor isolate

- Dem isolate

- Uhunduni (Damal, Amungme) isolate

- Mek family (13)

- ? Kaure–Kapori (4) [Inclusion in TNG tentative. No pronouns can be reconstructed from the available data.]

- ? Pauwasi family (4) [Inclusion in TNG tentative. No pronouns can be reconstructed from the available data. Since linked to Karkar, which is well attested and not TNG]

- Kayagar family (3)

- Kolopom family (3)

- Moraori isolate

- ? Kiwai–Porome (8) [TNG identity of pronouns suspect]

- Marind family (6)

- Central and South New Guinea ? (49, reduced) [Part of the original TNG proposal. Not clear if these four families form a single branch of TNG. Voorhoeve argues independently for an Awyu–Ok relationship.]

- Asmat–Kamoro family (11)

- Awyu–Dumut family (8–16)

- Mombum family (2)

- Ok family (20)

- Oksapmin isolate [now linked to the Ok family]

- Gogodala–Suki family (4)

- Tirio family (4)

- Eleman family (7)

- Inland Gulf family (6)

- Turama–Kikorian family (4)

- ? Teberan family [inclusion in TNG tentative] (2)

- ? Pawaia isolate [has proto-TNG vocabulary, but inclusion questionable]

- Angan family (12)

- ? Fasu (West Kutubuan) family (1–3) [has proto-TNG vocabulary, but inclusion somewhat questionable]

- ? East Kutubuan family (2) [has proto-TNG vocabulary, but inclusion somewhat questionable]

- Duna–Pogaya family (2)

- Awin–Pa family (2)

- East Strickland family (6)

- Bosavi family (8)

- Kamula isolate

- Engan family (9)

- Wiru isolate (lexical similarities with Engan)

- Chimbu–Wahgi family (17)

- Kainantu–Goroka (22) [also known as East Highlands; first noticed by Capell 1948]

- Madang (103)

- Southern Adelbert Range–Kowan

- Rai Coast–Kalam

- Croisilles linkage

- Dimir-Malas (2)

- Kaukombar (4)

- Kumil (5)

- Tibor-Omosa (6)

- Amaimon isolate

- Numugen-Mabuso

- Finisterre–Huon (62) [part of the original TNG proposal. Has verbs that are suppletive per the person and number of the object.]

- Finisterre family (41)

- Huon family (21)

- ? Goilalan family (6) [inclusion in TNG tentative]

- Southeast Papuan (Bird's Tail) ? [these families have not been demonstrated to be related to each other, but have in common ya for 'you[plural]' instead of proto-TNG *gi]

- Binanderean (16)

- Guhu-Samane isolate

- Binandere family (15) [a recent expansion from the north]

Unclassified Wurmian languages

Although Ross based his classification on pronoun systems, many languages in New Guinea are too poorly documented for even this to work. Thus there are several isolates that were placed in TNG by Wurm but that cannot be addressed by Ross's classification. A few of them (Komyandaret, Samarokena, and maybe Kenati) have since been assigned to existing branches (or ex-branches) of TNG, whereas others (Massep, Momuna) continue to defy classification.

- Kenati (→ Kainantu?)

- Komyandaret (→ Greater Awyu)

- Massep isolate

- Molof isolate

- Momuna family (2)

- Samarokena (→ Kwerba)

- Tofamna isolate

- Usku isolate

Reclassified Wurmian languages

Ross removed 95 languages from TNG. These are small families with no pronouns in common with TNG languages, but that are typologically similar, perhaps due to long periods of contact with TNG languages.

- Border and Morwap (Elseng), as an independent Border family (15 languages)

- Isirawa (Saberi), as a language isolate (though classified as Kwerba by Clouse, Donohue & Ma 2002)[5]

- Lakes Plain, as an independent Lakes Plain family (19)

- Mairasi, as an independent Mairasi family (4)

- Nimboran, as an independent Nimboran family (5)

- Piawi, as an independent Piawi family (2)

- Senagi, as an independent Senagi family (2)

- Sentani (4 languages), within an East Bird's Head – Sentani family

- Tor and Kwerba, joined as a Tor–Kwerba family (17)

- Trans-Fly – Bulaka River is broken into five groups: three remaining (tentatively) in TNG (Kiwaian, Moraori, Tirio), plus the independent South-Central Papuan and Eastern Trans-Fly families (22 and 4 languages).

Ethnologue

Ethnologue 16 (2009) largely follows Ross, but excludes the tentative Kaure–Kapori and Pauwasi branches, listing them as independent families. They also break up the Central and South New Guinea (Asmat–Ok) within TNG, though they maintain both Southeast Papuan (including Goilalan) and West Trans–New Guinea as units. Ethnologue 17 (2013) retains this classification, with the single change of splitting off the East Timor languages within West Trans–New Guinea.

Glottolog

Hammarström (2012) argued that Ross's pronouns appear to be a spurious signal and are not indicative of a language family.[3] Glottolog consequently takes a much more conservative view of the proposal, which it calls "Nuclear Trans–New Guinea". These are families that have been shown to be related by more than a few possibly chance resemblances in their pronouns:[1]

- Asmat–Kamoro

- Greater Awyu

- Binanderean

- Chimbu–Wahgi

- Dani

- Engan

- Finisterre–Huon

- Kainantu–Goroka

- Madang

- Mek

- Ok–Oksapmin

- Paniai Lakes

Note that even this scaled-down version of the family spans New Guinea and includes over 300 languages.

Phonology

Proto-Trans–New Guinea is reconstructed with a typical simple Papuan inventory: five vowels, /i e a o u/, three phonations of stops at three places, /p t k, b d ɡ, m n ŋ/ (Andrew Pawley reconstructs the voiced series as prenasalized /mb nd ŋɡ/), plus a palatal affricate /dʒ ~ ndʒ/, the fricative /s/, and the approximants /l j w/. Syllables are typically (C)V, with CVC possible at the ends of words. Many of the languages have word tone.

Pronouns

Ross reconstructs the following pronominal paradigm for Trans–New Guinea, with *a~*i ablaut for singular~non-singular:

I *na we *ni thou *ga you *gi s/he *(y)a, *ua they *i

There is a related but less commonly attested form for 'we', *nu, as well as a *ja for 'you', which Ross speculates may have been a polite form. In addition, there were dual suffixes *-li and *-t, and a plural suffix *-nV, (i.e. n plus a vowel) as well collective number suffixes *-pi- (dual) and *-m- (plural) that functioned as inclusive we when used in the first person. (Reflexes of the collective suffixes, however, are limited geographically to the central and eastern highlands, and so might not be as old as proto-Trans–New Guinea.)

Lexical words, such as *niman 'louse', may also be reconstructed:

- Reflexes of *niman 'louse', which attest to an intermediate *iman in the east:

- Chimbu: Middle Wahgi numan

- Engan: Enga & Kewa lema

- Finisterre–Huon: Kâte imeŋ, Selepet imen

- Gogodala mi

- Kainantu–Goroka: Awa nu, Tairora nume, Fore numaa, Gende (tu)nima

- S. Kiwai nimo

- Koiarian: Managalasi uma

- Kolopom: Kimaghana & Riantana nome

- Kwale nomone

- Madang: Kalam yman, Dumpu (Rai Coast) im, Sirva (Adelbert) iima

- Mek: Kosarek ami

- Moraori nemeŋk

- Paniai Lakes: Ekari yame (metathesis?)

- Timor–Alor–Pantar: West Pantar (h)amiŋ, Oirata amin (metathesis?)

- Wiru nomo

- Questionable braches:

- Pauwasi: Yafi yemar

- C. Sentani mi

See also

References

- ^ a b c Glottolog: Nuclear Trans–New Guinea

- ^ Doubtful according to Ross (2005)

- ^ a b Harald Hammarström (2012) "Pronouns and the (Preliminary) Classification of Papuan languages", Journal of the Linguistic Society of Papua New Guinea

- ^ [1]

- ^ Clouse, Duane; Donohue, Mark; Ma, Felix (2002). "Survey report of the north coast of Irian Jaya". SIL Electronic Survey Reports. 078.

Bibliography

- Pawley, Andrew (1998). "The Trans New Guinea Phylum hypothesis: A reassessment". In Jelle Miedema; Cecilia Odé; Rien A.C. Dam (eds.). Perspectives on the Bird's Head of Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Amsterdam: Rodopi. pp. 655–90. ISBN 978-90-420-0644-7. OCLC 41025250.

- Pawley, Andrew (2005). "The chequered career of the Trans New Guinea hypothesis: recent research and its implications". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 67–107. ISBN 0-85883-562-2. OCLC 67292782.

- Ross, Malcolm (2005). "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 15–66. ISBN 0858835622. OCLC 67292782.

- Wurm, Stephen A., ed. (1975). Papuan languages and the New Guinea linguistic scene: New Guinea area languages and language study 1. Canberra: Dept. of Linguistics, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University. OCLC 37096514.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)