User:Kaleeb18/sandbox

1967–1988: Roy O. Disney's leadership and death, Walt Disney World, animation industry decline, and Touchstone Pictures[edit]

In 1967, the last two films Walt had worked on were released, the animated film The Jungle Book, which would be Disney's best film for the next two decades, and the live-action musical The Happiest Millionaire.[1][2] After Walt's death, the company largely abandoned the animation industry, but would still make several live-action films.[3][4] Its staff in the field of animation began to decline from 500 workers to 125 employees, with the company only hiring 21 people from 1970 to 1977.[5] Disney's first post-Walt animated film The Aristocats was released in 1970, where Dave Kehr of Chicago Tribune said, "the absence of his [Walt's] hand is evident."[6] That following year the anti-fascist musical Bedknobs and Broomsticks was released and won the Oscar for Best Special Visual Effects.[7] By the time Walt had died, Roy was ready to retire, but wanted to keep Walt's legacy alive and became the first CEO and chairman of the board of the company.[8][9] In May 1967, He got a legislation passed by Florida's legislatures to grant Disney World's to have its own quasi-government agency in an area called the Reedy Creek Improvement District and later changed the name from Disney World to Walt Disney World to remind people it was Walt's dream.[10][11] Over time, EPCOT became less of the City of Tomorrow and developed more into another amusement park.[12] After 18 months of construction that costed around $400 million, Walt Disney World's first park the Magic Kingdom, along with Disney's Contemporary Resort and Disney's Polynesian Resort,[13] opened on October 1, 1971, with 10,400 visitors. A parade with over 1,000 band members, along with 4,000 Disney entertainers and choir from the U.S. Army, marched down Main Street led by composer Meredith Wilson. Unlike Disneyland, the icon of the park would be the Cinderella Castle instead of the Sleeping Beauty Castle. Three months later on Thanksgiving day, cars wanting to get into the Magic Kingdom were stretched miles along the interstate.[14][15]

On December 21, 1971, Roy died of cerebral hemorrhage at the St. Joseph Hospital.[9] After Roy's death, Donn Tatum, who was a senior executive for 25 years and former president of Disney, became the first non-Disney family member to become CEO and chairman of the board of the company, with Card Walker, who had been with the company since 1938, becoming president of the company.[16][17] By June 30, 1973, Disney had over 23,000 employees and had a gross total of $257,751,000 over a nine months period, which is a raise compared to the year before when they made $220,026,000.[18] In November, Disney released another animated film Robin Hood, which became Disney's biggest international grossing movie at $18 million.[19] Throughout the 1970s, Disney released several more live-action films such as The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes' sequal Now You See Him, Now You Don't,[20] The Love Bug's two sequals Herbie Rides Again (1974) and Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo (1977),[21][22] Escape to Witch Mountain (1975),[23] and Freaky Friday (1976).[24] In 1976, Card Walker took over as CEO of the company, with Tatum staying as the chairman until 1980 when Walker would replace him.[8][17] In 1977, Roy E. Disney, Roy O. Disney's son and the only Disney working for the company, would resign from his job as an executive of the company because of disagreements with decisions the company was making.[25]

In 1977, Disney's created the successful animated film The Rescuers, grossing $48 million at the box office.[26] The live-acton/animated musical Pete's Dragon was released in 1977, grossing $16 million in the U.S. and Canada, but was considered a disappointment to the company.[27][28] In 1979, Disney's first ever PG rated film and most expensive film at $26 million dollars The Black Hole was released, showing that Disney could also use special effects. Grossing $35 million, which was a disappointment to the company who thought it was going to be like Star Wars (1977), the film was in response to other sci-fi movies that were being released.[29][30] In September, 12 animators, over 15 percent of the department, resigned from the studio. Led by Don Bluth, they left because of a conflict with the training program and the atmosphere at the studio, starting their own company Don Bluth Productions (which later became Sullivan Bluth Studios).[31][32] In 1981, Disney released Dumbo to VHS and Alice in Wonderland the following year, eventually leading Disney to release all their films to home media.[33] On July 24, Walt Disney World on Ice, a two year tour of ice shows featuring Disney charters, made its premiere at the Brendan Byrne Meadowlands Arena, after Disney licensed its characters to Feld Entertainment.[34][35] The same month, Disney's animated film The Fox and the Hound was released and became the highest grossing animated film to that point at $39.9 million.[36] It was the first film that Walt had nothing to do with and was the last major work done by Disney's Nine Old Men, making way for the younger animators to do more.[5]

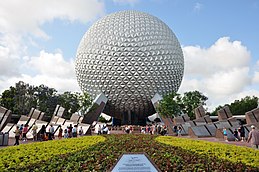

As profits for the company started to slow down, On October 1, 1982, Epcot, then known as EPCOT Center, opened as the second theme park in Walt Disney World, with around 10,000 people.[37][38] Costing the company over $900 million to construct, The park consisted of the Future World pavilion and the World Showcase which represented nine countries including Mexico, China, Germany, Italy, America, Japan, France, United Kingdom, and Canada (Morocco and Norway would be added later in 1984 and 1988, respectively).[37][39] The animation industry continued to decline and 69% of the companies profits were from its theme parks, with attendance of 12 million visitors to Walt Disney World which would decline by 5% next June.[37] On July 9, Disney released one of the first films to majorly use computer-generated imagery (CGI) Tron, which would a big influence on other CGI movies, although it only received mixed reviews.[40] In total in 1982, the company lost $27 million.[41] On April 15, 1983, Disney's first ever foreign park Tokyo Disneyland, similar to Disneyland and the Magic Kingdom, opened in Urayasu, Japan.[42] Costing around $1.4 billion, construction on the park started in 1979 when Disney and The Oriental Land Company agreed to build a park together. Within its first ten year, the park had been a hit with over 140 million visitors.[43] After an investment of $100 million, on April 18, Disney started a pay to watch cable television series called Disney Channel, a sixteen hour-long series showing things such as Disney films, twelve different programs, and two magazines shows for adults. Although it was expected to do well, the company loss $48.3 million after its first year, with 916,000 subscribers.[44][45]

In 1983, Walt's son-in-law Ron W. Miller, who had been president of the company since 1978, became CEO of Disney and Raymond Watson became chairmen.[8][46] Ron would push for more more mature films from the studio,[47] and as a result, Disney founded the film distribution label Touchstone Pictures to produce movies geared toward adults and teenagers in 1984.[41] Splash (1984), was the first film released under the label and would become a much needed success for the studio, grossing over $6.1 million in its first week of screening.[48] Later, Disney's first R-rated film Down and Out in Beverly Hills (1986) was released and was another hit for the company, grossing $62 million.[49] The following year, Disney's first PG-13 rated film Adventures in Babysitting was released.[50] In 1984, Saul Steinberg attempted to buyout the company, holding 11.1% of the stocks in the company. He offered to buy 49% of the company for $1.3 billion or the entire company for $2.75 billion. Disney, which had less than $10 million, rejected and offered to buy all of his stock for $325.5 million. Steinberg agreed and Disney payed it all with part of the $1.3 billion they borrowed from the bank, putting the company at $866 million in debt.[51][52]

1984–2005: Michael Eisner's leadership, the Disney Renaissance, merger, and acquisitions[edit]

In 1984, The companies shareholders, Roy E. Disney, Sid Bass, Lillian and Diana Disney, and Irwin L. Jacobs, who had a combined total of about 35.5% of the total shares of the company, forced Miller out as CEO and replaced him with Michael Eisner, who had previously been president of Paramount Pictures, as the new CEO, along with bringing in Frank Wells as president.[53] Eisner's first move at Disney was to make it a major film studio, which at the time it was not considered. He brought in Jeffrey Katzenberg as chairmen and Roy as head of the animation division to help with the animation industry. He wanted to produce an animated film every 18 months instead of every 4 years like the company had been doing. To help with the film division, they started making Saturday-morning cartoon to create new Disney characters for merchandising and producing several films through Touchstone. Eisner led Disney into the television industry more by creating Touchstone Television and producing The Golden Girls, which was a hit. The company also started to promote their theme parks for the first time at $15 million, raising the attendance rate by 10%.[54][55] In 1984, Disney created the most expensive animated movie at $40 million, and their first animated film to feature computer-generated imagery, as well as their first PG rated animated film because of its darker themes The Black Cauldron. It ended up being a box office bomb, leading the company to move the animation department out of studio in Burbank and into a warehouse in Glendale, California.[56] Organized in 1985, Silver Screen Partners II, LP financed films for Disney with $193 million. In January 1987, Silver Screen III began financing movies for Disney with $300 million raised, the largest amount raised for a film financing limited partnership by E.F. Hutton.[57] Silver Screen IV was also set up to finance Disney's studios.[58]

In 1986, the company changed its name from Walt Disney Productions to its current name The Walt Disney Company, saying that the old name only referred to the film entertainment industry.[59] With Disney's animation industry declining, the animation department needed a hit with their next movie The Great Mouse Detective. During its release, it grossed $25 million, becoming a much needed financial success for the company in the animation industry.[60] To generate more revenue from merchandising, the company opened their first retail store the Disney Store in Glendale in 1987. Because of its success, they opened two more stores in California, and by 1990 they had 215 stores throughout the country.[61][62] In 1989, the company saw financial success with $411 million in revenue and a profit of $187 million.[63] In 1987, the company signed an agreement with the French government to build a resort in Paris named Euro Disneyland, consisting of two theme parks named Disneyland Park and Walt Disney Studios Park, a golf course, and six hotels.[64][65]

In 1988, Disney's 27th animated film Oliver & Company was released the same day as former animator Don Bluth's The Land Before Time. Oliver & Company beat out The Land Before Time, becoming the first animated film to gross over $100 million in its initial release and the highest grossing animated film from its initial run.[66][67] At the time, Disney became the box office leader out of all the studios in Hollywood for the first time, with films such as Who Framed Rodger Rabbit (1988), Three Men and a Baby (1987), and Good Morning, Vietnam (1987). Gross revenue in 1983 was $165 million and went up to $876 million in 1987, and operating income went from a negative $33 million in 1983 to a positive 130 million in 1987. Their net income went up 66% along with a 26% growth in revenue. The Los Angeles Times called Disney's bounce back "a real rarity in the corporate world".[68] On May 1, 1989, Disney opened their third amusement park at Walt Disney World Hollywood Studios, which at the time went under the name Disney-MGM Studios. The park was mainly about how movies were made, until it changed by 2008 to make guest feel like they are in movies.[69] Following the opening of Hollywood Studios, Disney opened water park Typhoon Lagoon on June 1, 1989; in 2008, the water park had a total of 2.8 million people in attendance.[70] In 1989, Disney signed an agreement-in-principle to acquire Jim Henson Productions from its founder, Muppet creator Jim Henson. The deal included Henson's programming library and Muppet characters (excluding the Muppets created for Sesame Street), as well as Jim Henson's personal creative services. However, Henson died suddenly in May 1990 before the deal was completed, resulting in the two companies terminating merger negotiations the following December.[71][72][73]

On November 17, 1989, The Little Mermaid was released and is considered to be the start of the Disney Renaissance, a period in which the company released successful and critically acclaimed animated films. During its release, it became the animated film with the highest gross from it initial run and garnered $233 million at the box office; it also earned two Academy Awards, Best Original Score and Best Original Song for “Under the Sea”.[74][75] During the Disney Renaissance, several of Disney's songs were written by composer Alan Menken and lyricist Howard Ashman, until Howard died in 1991. Together they wrote six songs that were nominated for Academy Awards, with two winning, "Under The Sea" and "Beauty and the Beast".[76][77] In September 1990, Disney arranged for financing up to $200 million by a unit of Nomura Securities for Interscope films made for Disney. On October 23, Disney formed Touchwood Pacific Partners which would supplant the Silver Screen Partnership series as their movie studios' primary source of funding.[58] Disney's first animated sequal The Rescuers Down Under was released on November 16, 1990, and was created using Computer Animation Production System (CAPS), a digital software which was developed by Disney and the computer division of Lucasfilm Pixar, becoming the first feature film to be fully created digitally.[75][78] Although the film struggled in the box office, grossing $47.4 million, it received positive reviews from critics.[79][80] In 1991, Disney and Pixar agreed to a deal to make three films together, with the first one being Toy Story.[81]

To produce music geared for the mainstream music, including music for movie soundtracks, Disney founded the recording label Hollywood Records on January 1, 1990.[82][83] Disney's next animated film Beauty and the Beast was released on November 13, 1991, and grossed nearly $430 million.[84][85] It was the first animated film to win a Golden Globe for Best Picture, and it received six Academy Award nominations, becoming the first animated film to be nominated for Best Picture Oscar; It won Best Score, Best Sound, and Best Song for "Beauty and the Beast".[86] The film was critically acclaimed, with some considering it to be the best Disney film.[87][88] To coincide with their new release The Mighty Ducks, Disney founded NHL team The Mighty Ducks of Anaheim in 1992.[89] Disney's next animated feature Aladdin was released on November 11, 1992, and grossed $504 million, becoming the highest-grossing animated film up to that point, and the first animated film to reach the half-billion-dollar mark.[90][91] It won two Academy Awards for Best Song for "A Whole New World" and Best Score;[92] "A whole New World" was the first and only Disney song to win the Grammy for Song of the Year.[93][94] For $60 million, Disney broadened their more mature films by acquiring independent film distributor Miramax Films in 1993.[95] In a joint venture with The Nature Conservancy, Disney purchased 8,500 acres (3,439 ha) of Everglades headwaters in Florida in 1993 to protect native animals and plant species, establishing the Disney Wilderness Preserve.[96]

On April 3, 1994, Frank Wells died in a helicopter crash, while on a vacation to go skiing. He, Eisner, and Katzenburg helped the company's market value go from $2 billion to $22 billion since taking office in 1984.[97] On June 15, The Lion King was released and was a massive success. It became the second highest-grossing film of all time behind Jurassic Park and the highest-grossing animated film of all time, with a gross total of $986 million.[98][99] It garnered two Academy Awards for Best Score and Best Song for "Can You Feel the Love Tonight" and was critically praised.[100][101] Soon after its release, Katzenburg left the company after Eisner would not promote him to president. After leaving, he co-founded film studio DreamWorks SKG.[102] Well's spot was later replaced by one of Eisner's friends Michael Ovitz on August 13, 1995.[103][104] In 1994, Disney had been looking to buy one of the big three networks, ABC. NBC, and CBS, which would give them guaranteed distribution for its programming. Eisner sought out to buy NBC, but the deal was cancelled once he heard General Motors wanted to keep a majority stake.[105][106] In 1994, Disney reached $10.1 billion in revenue, with the film industry being 48% of the total, the theme parks being 34%, and 18% of it from merchandising. Disney's total net income was up 25% from last year at $1.1 billion.[107] Grossing over $346 million, Pocahontas was released on June 16, garnering the Academy Awards for Best Musical or Comedy Score and Best Song for "Colors of the Wind".[108][109] Pixar and Disney's first release together was the first-ever fully computer-generated film Toy Story. It was released on November 19, 1995, to critical acclaim and an end-run gross total of $361 million. The film won the Special Achievement Academy Award, as well as being the first animated film to be nominated for Best Original Screenplay.[110][111]

In 1995, Disney announced a $19 billion merger of equals with Capital Cities/ABC Inc., which at the time was the second largest corporate takeover. Through the deal, Disney would obtain broadcast network ABC, an 80% majority stake in sports network ESPN and ESPN 2, 50% in Lifetime Television, a majority stake of DIC Entertainment, and a 37.5% minority stake in A&E Television Networks.[107][112][113] Following the deal, the company started a radio program focused for youth on ABC Radio Network called Radio Disney on November 18, 1996.[114][115] The Walt Disney Company launched its official website disney.com on February 22, mainly to promote their theme parks and give information on its merchandise.[116] On June 19, the companies' next animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame was released, grossing $325 million at the box office.[117] Because Ovitz's management style was different from Eisner's, Ovitz was fired as president of the company in 1996.[118] Disney lost a $10.4 million lawsuit in September 1997 to Marsu B.V. over Disney's failure to produce as contracted 13 half-hour Marsupilami cartoon shows. Instead, Disney felt other internal "hot properties" deserved the company's attention.[119] With a 25% stake in the California Angels, Disney bought out the team in 1998 for $110 million, renaming the team to the Anaheim Angels and renovating their stadium for $100 million.[120][121] Hercules was was released on June 13 and under preformed at the box office compared to the previous films, grossing $252 million.[122] On February 24, Disney and Pixar signed a ten-year contract to make 5 films together, with Disney as the distributor. They would share the cost, profits, and logo credits, calling the films a Disney-Pixar production.[123] During the Disney Renaissance, film division Touchstone Pictures also saw success, with film such as Pretty Woman (1990), which has the highest number of ticket sales in the US for a romantic comedy and grossed $432 million;[124][125] Sister Act (1992), which was one of the more financially successful comedies of the early 1990s, grossing $231 million;[126] action film Con Air (1997), which grossed $224 million;[127] and the highest-grossing film of 1998 at $553 million Armageddon (1998).[128]

At Disney World, the company opened the largest theme park in the world covering 580 acres (230 ha) Disney's Animal Kingdom on Earth Day, April 22, 1998. It is made up of six lands based off zoological themes, with the Tree of Life as the park's centerpiece and over 2,000 animals.[129][130] Receiving positive reviews, Disney's next animated films, Mulan and Disney-Pixar film A Bug's Life, were released on June 5 and November 20, respectively.[131][132] Mulan became the sixth highest-grossing film of 1998 at $304 million, and A Bug's Life was the fifth highest at $363 million.[128] In a $770 million transaction, on June 18, Disney bought a 43% stake of Internet search engine Infoseek for $70 million, also giving Infoseek earlier acquired Starwave.[133][134] With negotiations between Carnival and Royal Caribbean not going well, in 1994, Disney announced they would start their own cruise line operations starting in 1998.[135][136] The first two ships part of the Disney Cruise Line would be named Disney Magic and Disney Wonder and would be built by Fincantieri in Italy. To accompany the cruises, Disney bought Gorda Cay as the line's private island and spent $25 million on remodeling it and renamed it Castaway Cay. On July 30, 1998, Disney Magic set sail as the line's first voyage.[137] Starting web portal Go.com in a joint venture with Infoseek on January 12, 1999, Disney later acquired the rest of Infoseek that year.[138][139]

Marking the end of the Disney Renaissance, Tarzan was released on June 12, garnering $448 million at the box office and critical acclaim; it also claimed the Academy Award for Best Original Song for Phil Collins' "You'll Be in My Heart".[140][141][142][143] Toy Story's sequal and Disney-Pixar film Toy Story 2 was released on November 13 as a successful film, garnering praise and $511 million at the box office.[144][145] Filling Ovitz spot, Eisner named ABC network chief Bob Iger president and COO of the company on January 25, 2000.[146][147] In November, Disney sold DIC Entertainment back to Andy Heward, although still doing business with them.[148] Disney had another huge success with Pixar when they released Monsters, Inc. in 2001. Later, Disney bought children's cable network Fox Family Worldwide for $3 billion and the assumption of $2.3 billion in debt. The deal also included 76% stake in Fox Kids Europe, Latin American Fox Kids, more than 6,500 episodes from Saban Entertainment's programming library, and the Fox Family Channel.[149] In 2001, Disney's operations declined with a a net loss of $158 million in fiscal, as well as a decline in viewership on the ABC television network, because of decreased tourism due to the September 11 attacks; Disney earning in fiscal 2001 $120 million was heavily reduced from the year's before $920 million. To help with costs savings, Disney announced they would be laying off 4,000 employees and closing 300 to 400 Disney stores.[150][151] After winning the world series in 2002, Disney sold the Angels to businessman Arturo Moreno for $180 million in 2003.[152][153] In 2003, Disney became the first studio to garner $3 billion in a year at the box office.[154] Roy Disney announced his retirement in 2003 because of the way the company was being ran, calling on Eisner to retire; the same week, board member Stanley Gold retired for the same reasons, forming the "Save Disney" campaign together.[155][156]

In 2004, at the companies annual meeting, the shareholders, in a 43% vote, voted Eisner out of his position as chairmen of the board.[157] On March 4, George J, Mitchell, who was a member of the board, was named as Eisner's replacement.[158] In April, Disney purchased The Muppets franchise from The Jim Henson Company for $75 million, founding The Muppets Studio in the process.[159][160] Following the massive success of Disney-Pixar films The Incredibles (2004) and Finding Nemo (2003), which became the second highest-grossing animated film of all time at $936 million,[161][162] Pixar looked for a new distributor once their deal with Disney ended in 2004.[163] After the Disney Stores were struggling, Disney sold the chain of 313 stores to Children's Place on October 20.[164] Disney also sold the Mighty Ducks NHL team to Henry Samueli and his wife Susan in 2005.[165] Roy decided to rejoin the company and was given the role of a consultant with the title of "Director Emeritus".[166]

2005–2020: Bob Iger's leadership, buyout of Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, and 21st Century Fox, and Disney+[edit]

In March, it was announced that Bob Iger, president of the company, would become CEO of Disney after Eisner's retirement in September; Iger was officially named head of the company on October 1.[167][168] Disney's eleventh theme park Hong Kong Disneyland opened in Hong Kong, China, on September 12, costing the company $3.5 billion to make.[169] On January 24, 2006, Disney made a move to acquire Pixar from Steve Jobs for $7.4 billion. Iger made Pixar CCO John Lasseter and president Ed Catmull the head of the Walt Disney Animation Studios.[170][171] A week later, Disney traded ABC sports commentator Al Michaels to NBCUniversal to get back the rights to Oswald the Lucky Rabbit and the old 26 Oswald shorts.[172] On February 6, the company announced they would be merging its ABC Radio networks and 22 stations with Citadel Broadcasting in a $2.7 billion deal. Through the deal, Disney also acquired 52% of television broadcasting company Citadel Communications.[173][174] Disney Channel movie High School Musical aired and its soundtrack went triple platinum, being the first Disney Channel film to do so.[175]

Disney's 2006 live-action film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest was Disney's biggest hit to that date and the third highest grossing film ever, making a little over $1 billion at the box office.[176] On June 28, the company announced they would be replacing George Mitchell as chairmen with one of their board members and former CEO of P&G John E. Pepper Jr. In 2007.[158] The sequal High School Musical 2 was released in 2007 on Disney Channel and broke cable rating records.[177] In April 2007, the Muppets Holding Company was moved from Disney Consumer Products to the Walt Disney Studios division and renamed The Muppets Studio, as part of efforts to re-launch the division.[178][179] Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End became the highest-grossing film of 2007 at $960 million.[180] Disney-Pixar films Ratatouille (2007) and WALL-E (2008) are tremendous success, with WALL-E the Oscar for Best Animated Feature.[181][182][183] After acquiring most of Jetix Europe through the acquisition of Fox Family Worldwide, Disney took full control of the company in 2008 for $318 million.[184]

Bob Iger introduced D23 in 2009 as Disney's official fan club, with a biennial exposition event D23 Expo.[185][186] In February, Disney later announced a distributing deal with DreamWorks to distribute 30 of their films over the next 5 years through Touchstone Pictures, with Disney getting 10% of the gross.[187][188] With the release of the widely popular film Up, Disney garnered $735 million at the box office, with the film also winning Best Animated Feature at the Oscars.[189][190] Later, Disney launched a television channel geared towards older children named Disney XD.[191] Disney bought full control of Marvel Entertainment and its assets in August for $4 billion, adding superheros available for merchandising.[192] In September, Disney partnered with News Corp and NBCUniversal in a deal to each get 27% equity in streaming service Hulu, adding ABC Family and Disney Channel to the streaming service.[193] On December 16, Roy E. Disney died of stomach cancer as the last person in the Disney family to actively work for Disney.[194] In March 2010, Haim Saban reacquired the Power Rangers franchise, including its 700-episode library, from Disney for around $100 million.[195][196] Shortly after, Disney sold Miramax Films to an investment group headed by Ronald Tutor for $660 million.[197] During that time, Disney released the live-action Alice in Wonderland and Disney-Pixar film Toy Story 3 which grossed a little over $1 billion, making it the sixth and seventh film to do so, with Toy Story 3 becoming the first animated film to make over $1 billion and highest-grossing animated film. That year, Disney became the first studio to release two $1 billion films in a single year.[198][199] After starting ImageMovers Digital with ImageMovers in 2007, Disney announced that it would be closing by 2011 in 2010.[200]

The following year, Disney released their last traditionally animated film Winnie the Pooh to theaters.[201] The release of Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides took in a little over $1 billion, making it the eight film to do so and Disney's highest-grossing film internationally, as well as the third highest ever.[202] In January 2011, Disney Interactive Studios was downsized, laying off 200 employees.[203] In April, Disney broke ground on new theme park Shanghai Disney Resort, costing $4.4 billion to make.[204] Later, in August, Bob Iger stated on a conference call that after the success of the Pixar and Marvel purchases, he and The Walt Disney Company are looking to "buy either new characters or businesses that are capable of creating great characters and great stories."[205] On October 30, 2012, Disney announced that they would be buying Lucasfilm Ltd. for $4.05 billion from George Lucas. Through the deal Disney gained access to franchises such as Star Wars, which they said that they would make a new film for every 2 to 3 years with the first one being released in 2015, and Indiana Jones, as well as visual effects studio Industrial Light & Magic and video game developer LucasArts.[206][207] The sale was later completed on December 21, 2012.[208]

Later, in early February 2012, Disney completed its acquisition of UTV Software Communications, expanding their market further into India and Asia.[209] Marvel film The Avengers became the third highest-grossing film of all time at an initial release gross of $1.3 billion.[210] Making over $1.2 billion at the box office, Marvel film Iron Man 3 was released as a huge success in 2013.[211] The same year, Disney's animated film Frozen was released and became the highest-grossing animated film of all time at $1.2 billion.[212][213] Merchandising for the film became so popular that they made $1 billion off of it within a year and a global shortage of merchandise for the film occurred.[214][215] In March 2013, Iger announced that there were no 2D animation films in development and a month later the hand-drawn division of animation was closed, with several veterans being laid off.[201] On March 24, 2014, Disney acquired Maker Studios, an active multi-channel network on YouTube, for $950 million.[216]

On February 5, 2015, it was announced that Thomas O. Staggs had been promoted to COO.[217] In June, Disney stated that its consumer products and interactive divisions would merge together to create new a subsidiary of the company Disney Consumer Products and Interactive Media.[218] In August, Marvel Studios was reorganized and placed under Walt Disney Studios.[219] After the release of the successful animated film Inside Out, which grossed over $800 million, Marvel film Avengers: Age of Ultron was released a grossed over $1.4 billion.[220][221] Star Wars: The Force Awakens was released and grossed over $2 billion, making it the third highest-grossing film of all time.[222] In October, Disney announced that television channel ABC Family would be changing its name to Freeform in 2016, with the goal to broaden its audience coverage.[223][224] On April 4, 2016, Disney announced that COO Thomas O. Staggs, who was thought to be next in line after Iger, and the company had mutually agreed to part ways, effective May 2016, ending his 26-year career with the company.[225] After breaking ground in 2012, Shanghai Disneyland opened on June 16, 2016, as the company's sixth theme park resort.[226] In a move to start a streaming service, Disney bought 33% of the stock in MLB technology company BAMtech for $1 billion in August.[227] In 2016, Disney had four films making over $1 billion, which were the1 animated film Zootopia, Marvel film Captain America: Civil War, Pixar film Finding Dory, and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, making Disney the first studio to surpass $3 billion at the domestic box office.[228][229] Disney also made an attempt to buy social media platform Twitter to market their content and merchandise on, but ultimately dropped out of the deal. Iger stated that the reason was because he thought the company would be taking on responsibilities it didn't need to and that it didn't "feel Disney" to him.[230]

On March 23, 2017, Disney announced that Iger had agreed to a one-year extension of his term as CEO through July 2, 2019, and had agreed to remain with the company as a consultant for three years after stepping down.[231][232] On August 8, 2017, Disney announced it would be ending its distribution deal with streaming service Netflix, with the intent to launch its own streaming platform by 2019 built off BAMtech's technology. During that time, Disney made an investment of $1.5 billion to acquire a 75% stake in BAMtech. Disney also planned to start an ESPN streaming service with about "10,000 live regional, national, and international games and events a year" by 2018.[233][234] In November, CCO John Lasseter said that he would take a six-month absence from the company because of "missteps", which was later reported to be sexual misconduct allegations.[235] The same month, Disney and 21st Century Fox were negotiating a deal where Disney would acquire most of Fox's assets.[236] Beginning in March 2018, a strategic reorganization of the company saw the creation of two business segments, Disney Parks, Experiences and Products and Direct-to-Consumer & International. Parks & Consumer Products was primarily a merger of Parks & Resorts and Consumer Products & Interactive Media. While Direct-to-Consumer & International took over for Disney International and global sales, distribution and streaming units from Disney-ABC TV Group and Studios Entertainment plus Disney Digital Network.[237] While CEO Iger described it as "strategically positioning our businesses for the future", The New York Times considered the reorganization done in expectation of the 21st Century Fox purchase.[238]

In 2017, Disney had two film go over the $1 billion mark, the live-action Beauty and the Beast and Star Wars: The Last Jedi.[239][240] Disney launched subscription sports streaming service ESPN+ on April 12.[241] In June 2018, Disney declared that Lasseter would be leaving the company by the end of the year, staying as a consultant until then.[242] As his replacement, Disney promoted Jennifer Lee, co-director of Frozen and co-writer of Wreck-it Ralph (2012), as head of Walt Disney Animation Studios and Pete Doctor, who had been with Pixar since 1990 and directed Up, The Incredibles, and Inside Out, as head of Pixar.[243][244] Later that month, Comcast offered to buy 21st Century Fox for $65 billion over Disney's $51 billion bid, but withdrew from their offer after Disney countered at $71 billion, with Comcast shifting their focus to buy Sky plc instead. Disney also obtained an antitrust approval from the United States Department of Justice to acquire Fox.[245][246] Disney made $7 billion at the box office again like they did in record-breaking year 2016 with three film that made $1 billion, Marvel films Black Panther and Avengers: Infinity War and Pixar film Incredibles 2, with Infinity War surpassing $2 billion and becoming the fifth highest-grossing film ever.[247][248]

On March 20, 2019, Disney acquired 21st Century Fox's assets for $71.3 billion from owner Rupert Murdoch, making it the biggest acquisition in Disney's history. After the purchase, The New York Times described Disney as "an entertainment colossus the size of which the world has never seen."[249] Through the acquisition, Disney gained 20th Century Fox, 20th Century Fox Television, Fox Searchlight, Fox Networks Group, Indian television broadcaster Star India, and a 30% stake in Hulu, which brought its total up to 60% ownership of the company. Fox Corporation and its assets were excluded from the deal because of antitrust laws.[250] Disney also became the first film studio to have seven films gross $1 billion, which were Marvel's Captain Marvel, the live action Aladdin, Pixar's Toy Story 4, the CGI remake of The Lion King, Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker, and the highest-grossing film of all time up to that point at $2.797 billion Avengers: Endgame, before Avatar (2009) was rerelease in China in 2021.[251][252] On November 12, Disney's subscription video on-demand over-the-top streaming service Disney+, which had 500 movies and 7,500 episodes of TV shows from Disney, Pixar, Marvel, Star Wars, National Geographic and other brands, was launched in the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands. Within the first day, the streaming platform had over 10 million subscriptions and by 2022 it had over 135 million subscribers and was in over 190 countries.[253][254] At the beginning of 2020, Disney dropped the Fox name from all its assets rebranding it as 20th Century Studios and Searchlight Pictures.[255]

2020–present: Bob Chapek's leadership and COVID-19 pandemic[edit]

Bob Chapek, who had been with the company for 18 years and was chairman of Disney Parks, Experiences and Products, became CEO of Disney after Iger stepped down on February 25, 2020. Iger said that he would stay with the company as an executive chairmen until December 31, 2021, to help with the company's creative strategy.[256][257] In April, Iger resumed operational duties of the company as executive chairman to help the company during the COVID-19 pandemic and Chapek was appointed to the board of directors.[258][259] During the COVID-19 pandemic, Disney closed all of its theme park, delayed several movies that were to be released, and stopped all operations on their cruise line.[260][261][262] Due to the closures, Disney announced that they would stop paying 100,000 employees, but would still provide full healthcare benefits along with urging the U.S. employees to apply for government benefits through the $2 trillion stimulus check, saving the company $500 million a month. In addition, Iger gave up his entire $47.5 million salary and Chapek took a 50% reduction to his salary.[263]

In the company's second fiscal quarter of 2020, Disney reported a $1.4 billion loss, with their earnings dropping by 91% from last years $5.4 billion down to $475 million.[264] In September, the company had to fire 28,000 employees, 67% of which were part-time workers, from its Parks, Experiences and Products division. Chairman of the division Josh D'Amaro wrote "We initially hoped that this situation would be short-lived, and that we would recover quickly and return to normal. Seven months later, we find that has not been the case." Additionally, Disney lost a total of $4.7 billion in its fiscal third quarter of 2020.[265] In November, Disney layed off another 4,000 employees from the Parks, Experiences and Products division, rising the total to 32,000 employees.[266] The following month, Disney named Alan Bergman as chairman of its Disney Studios Content division to oversee its film studios.[267] Due to the COVID-19 recession, Disney shutdown 20th Century Studios' animation studio Blue Sky Studios in February 2021.[268] With Touchstone Television ceasing operations in December, Disney announced in March 2021 that it would be launching a new division of the company 20th Television Animation to focus on mature audiences.[269][270] In April, Disney and Sony agreed to a multiyear licensing deal that would give Disney assess to Sony's films from 2022 to 2026 to air on their television networks or stream on Disney+ once Sony's deal with Netfix ends.[271]

After Iger's term was over as executive chairman on December 31, he also announced that he would step down as chairman of the board. To replace him, the company brought in operating executive at The Carlyle Group and current board member Susan Arnold as Disney's first ever woman chairman.[272] On March 10, Disney ceased all operations it was doing in Russia because of Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Disney was the first major Hollywood studio to halt the release of a major motion picture due to Russia's invasion, and other movie studios followed soon after.[273] In March 2022, around 60 employees protested the company's response about staying silent on the Florida Parental Rights in Education Act, also dubbed the Don't Say Gay Bill, which prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity in a manner that is not age appropriate in Florida's public school districts. Dubbed as the "Disney Do Better Walkout", the employees protested near a Disney studios lot for about a week, with other employees voicing their concerns through social media. With employees calling on Disney to stop campaign contributions to Florida's politicians who supported the bill, to help protect employees from it, and to stop construction at Walt Disney World in Florida, Chapek responded by stating that the company had made a mistake by staying silent and said, "We pledge our ongoing support of the LGBTQ+ community".[274][275]

Amid Disney's response to the bill, Florida legislatures passed a bill to remove Disney's quasi-government district, with Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signing the bill effective June 1.[276] On June 28, Disney's board members unanimously agreed to give Chapek a three-year contract extension.[277]

Film library[edit]

Highest-grossing films[edit]

|

|

Revenues[edit]

| Year | Studio Entertainment[a] | Disney Consumer Products[b] | Disney Interactive Media[280][281] | Parks & Resorts[c] | Disney Media Networks[d] | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 2,593.0 | 724 | 2,794.0 | 6,111 | [282] | ||

| 1992 | 3,115 | 1,081 | 3,306 | 7,502 | [282] | ||

| 1993 | 3,673.4 | 1,415.1 | 3,440.7 | 8,529 | [282] | ||

| 1994 | 4,793 | 1,798.2 | 3,463.6 | 359 | 10,414 | [283][284][285] | |

| 1995 | 6,001.5 | 2,150 | 3,959.8 | 414 | 12,525 | [283][284][285] | |

| 1996 | 10,095[b] | 4,502 | 4,142[e] | 18,739 | [284][286] | ||

| 1997 | 6,981 | 3,782 | 174 | 5,014 | 6,522 | 22,473 | [287] |

| 1998 | 6,849 | 3,193 | 260 | 5,532 | 7,142 | 22,976 | [287] |

| 1999 | 6,548 | 3,030 | 206 | 6,106 | 7,512 | 23,435 | [287] |

| 2000 | 5,994 | 2,602 | 368 | 6,803 | 9,615 | 25,402 | [288] |

| 2001 | 7,004 | 2,590 | 6,009 | 9,569 | 25,790 | [289] | |

| 2002 | 6,465 | 2,440 | 6,691 | 9,733 | 25,360 | [289] | |

| 2003 | 7,364 | 2,344 | 6,412 | 10,941 | 27,061 | [290] | |

| 2004 | 8,713 | 2,511 | 7,750 | 11,778 | 30,752 | [290] | |

| 2005 | 7,587 | 2,127 | 9,023 | 13,207 | 31,944 | [291] | |

| 2006 | 7,529 | 2,193 | 9,925 | 14,368 | 34,285 | [291] | |

| 2007 | 7,491 | 2,347 | 10,626 | 15,046 | 35,510 | [292] | |

| 2008 | 7,348 | 2,415 | 719 | 11,504 | 15,857 | 37,843 | [293] |

| 2009 | 6,136 | 2,425 | 712 | 10,667 | 16,209 | 36,149 | [294] |

| 2010 | 6,701[f] | 2,678[f] | 761 | 10,761 | 17,162 | 38,063 | [295] |

| 2011 | 6,351 | 3,049 | 982 | 11,797 | 18,714 | 40,893 | [296] |

| 2012 | 5,825 | 3,252 | 845 | 12,920 | 19,436 | 42,278 | [297] |

| 2013 | 5,979 | 3,555 | 1,064 | 14,087 | 20,356 | 45,041 | [298] |

| 2014 | 7,278 | 3,985 | 1,299 | 15,099 | 21,152 | 48,813 | [299] |

| 2015 | 7,366 | 4,499 | 1,174 | 16,162 | 23,264 | 52,465 | [300] |

| 2016 | 9,441 | 5,528 | 16,974 | 23,689 | 55,632 | [301] | |

| 2017 | 8,379 | 4,833 | 18,415 | 23,510 | 55,137 | [302] | |

| 2018 | 9,987 | 4,651 | 20,296 | 24,500 | 59,434 | [303] | |

| Year | Studio Entertainment | Direct-to-Consumer & International | Parks, Experiences and Products | Media Networks[d] | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 10,065 | 3,414 | 24,701 | 21,922 | 59,434 | [304] |

| 2019 | 11,127 | 9,349 | 26,225 | 24,827 | 69,570 | [305] |

| 2020 | 9,636 | 16,967 | 16,502 | 28,393 | 65,388 | [306] |

| Year | Media and Entertainment Distribution | Parks, Experiences and Products | Total | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 50,866 | 16,552 | 67,418 | [307] |

Disney ranked No. 55 in the 2018 Fortune 500 list of the largest United States corporations by total revenue.[308]

36 grammys [g]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Also named Films and Film Entertainment

- ^ a b Merged into Creative Content in 1996, merged into Consumer Products and Interactive Media in 2016, which merged with Parks & Resorts in 2018

- ^ Called Walt Disney Attractions (1989–2000) Walt Disney Parks and Resorts (2000–2005) Disney Destinations (2005–2008) Walt Disney Parks and Resorts Worldwide (2008–2018)

- ^ a b Broadcasting from 1994 to 1996

- ^ Following the purchase of Capital Cities/ABC Inc.

- ^ a b first year with Marvel Entertainment as part of results

- ^ [309][310][311][312][313][314][315][316][317][318][319][320][321][322][323][324][325][326]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Canemaker 2001, p. 51; Griffin 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Spiegel, Josh (January 11, 2021). "A Crash Course in the History of Disney Animation Through Disney+". Vulture. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (March 26, 2016). "Waking Sleeping Beauty documentary takes animated look at Disney renaissance". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Lambie, Ryan (June 26, 2019). "Exploring Disney's Fascinating Dark Phase of the 70s and 80s". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Sito, Tom (November 1, 1998). "Disney's The Fox and the Hound: The Coming of the Next Generation". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Dave, Kehr (April 13, 1987). "Aristocats Lacks Subtle Disney Hand". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Long, Rebecca (August 8, 2021). "The Anti-Fascist Bedknobs and Broomsticks Deserves Its Golden Jubilee". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ a b c Radulovic, Petrana (February 27, 2020). "Your complete guide to what the heck the Disney CEO change is and why you should care". Polygon. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ a b "Roy O. Disney, Aide of Cartoonist Brother, Dies at 78". The New York Times. December 22, 1971. p. 39. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Eades, Mark (December 22, 2016). "Remembering Roy O. Disney, Walt Disney's brother, 45 years after his death". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ Levenson, Eric; Gallagher, Dianna (April 21, 2022). "Why Disney has its own government in Florida and what happens if that goes away". CNN. Archived from the original on May 22, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Matt, Patches (May 20, 2015). "Inside Walt Disney's Ambitious, Failed Plan to Build the City of Tomorrow". Esquire. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ "49 years ago, Walt Disney World opened its doors in Florida". Fox 13 Tampa Bay. October 1, 2021. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (September 29, 2021). "Disney World Opened 50 Years Ago; These Workers Never Left". Associated Press. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ Greg, Allen (October 1, 2021). "50 years ago, Disney World opened its doors and welcomed guests to its Magic Kingdom". NPR. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Donn B. Tatum". Variety. June 3, 1993. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ a b "E. Cardon 'Card' Walker". Variety. November 30, 2005. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Empire Is Hardly Mickey Mouse". The New York Times. July 18, 1973. p. 30. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Disney's Dandy Detailed Data; Robin Hood Takes $27,500,000; Films Corporate Gravy-Maker". Variety. January 15, 1975. p. 3.

- ^ Thompson, Howard (August 24, 1972). "Spirited Romp for Invisible Caper Crew". The New York Times. p. 0. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Herbie Rides Again". Variety. December 31, 1973. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ "Herbie Goes to Monte Carlo". Variety. December 31, 1977. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (July 3, 1975). "Screen: Witch Mountain: Disney Fantasy Shares Bill with Cinderella". The New York Times. p. 0. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Eder, Richard (January 29, 1977). "Disney Film Forces Fun Harmlessly". The New York Times. p. 11. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2022.

- ^ Schneider, Mike (November 3, 1999). "Nephew Is Disney's Last Disney". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ King, Susan (June 22, 2015). "Disney's animated classic The Rescuers marks 35th anniversary". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 31, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Lucas 2019, p. 89.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1978". Variety. January 3, 1979. p. 17.

- ^ Kit, Borys (December 1, 2009). "Tron: Legacy team mount a Black Hole remake". Reuters. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Weiner, David (December 13, 2019). ""We Never Had an Ending:" How Disney's Black Hole Tried to Match Star Wars". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (September 20, 1979). "11 Animators Quit Disney, Form Studio". The New York Times. p. 14. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Poletick, Rachel (February 2, 2022). "Don Bluth Entertainment: How One Animator Inspired a Disney Exodus". Collider. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Lucas 2019, p. 153.

- ^ "World on Ice Show Opens July 14 in Meadowlands". The New York Times. Associated Press. June 28, 1981. p. 48. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Sherman, Natalie (April 7, 2014). "Howard site is a key player for shows like Disney on Ice and Monster Jam". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2022.

- ^ Eller, Claudia (January 9, 1990). "Mermaid Swims to Animation Record". Variety. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Thomas, Hayes (October 2, 1982). "Fanfare as Disney Opens Park". The New York Times. p. 33. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Wynne, Sharron Kennedy (September 27, 2021). "For Disney World's 50th anniversary, a look back at the Mouse that changed Florida". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ "On This Day: Epcot opened at Walt Disney World in 1982". Fox 35 Orlando. October 1, 2021. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ King, Susan (January 7, 2017). "Tron at 35: Star Jeff Bridges, Creators Detail the Uphill Battle of Making the CGI Classic". Variety. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Harmetz, Aljean (February 16, 1984). "Touchstone Label to Replace Disney Name on Some Films". The New York Times. p. 19. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Shoji, Kaori (April 12, 2013). "Tokyo Disneyland turns 30!". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Shapiro, Margaret (December 16, 1989). "Unlikely Tokyo Bay Site Is a Holiday Hit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Bedell, Sally (April 12, 1983). "Disney Channel to Start Next Week". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Steve, Knoll (April 29, 1984). "The Disney Channel Has an Expensive First Year". The New York Times. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Raymond Watson, former Disney chairman, dies". Variety. October 22, 2012. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Bartlett, Rhett (February 10, 2019). "Ron Miller, Former President and CEO of The Walt Disney Co., Dies at 85". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 25, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Disney makes big splash at box office". UPI. March 12, 1984. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (March 13, 2021). "Hollywood Flashback: Down and Out in Beverly Hills Mocked the Rich in 1986". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Chapman, Glenn (March 29, 2011). "Looking back at Adventures in Babysitting". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Sanello, Frank (June 11, 1984). "Walt Disney Productions ended financier Saul Steinberg's takeover attempt..." UPI. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (June 12, 1984). "Steinberg Sells Stake to Disney". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 26, 2022. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Thomas (September 24, 1984). "New Disney Team's Strategy". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Aljean, Harmentz (December 29, 1985). "The Man Re-animating Disney". The New York Times. p. 13. Archived from the original on June 2, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (May 20, 2020). "The Disney Renaissance Didn't Happen Because of Jeffrey Katzenberg; It Happened in Spite of Him". Collider. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Kois, Dan (October 19, 2010). "The Black Cauldron". Slate. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ "Breifly: E. F. Hutton raised $300 million for Disney". Los Angeles Times. February 3, 1987. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; May 3, 2014 suggested (help) - ^ a b "Disney, Japan Investors Join in Partnership : Movies: Group will become main source of finance for all live-action films at the company's three studios". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. October 23, 1990. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Change". The New York Times. January 4, 1986. p. 33. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Harrison, Mark (November 21, 2019). "The Sherlockian Brilliance of The Great Mouse Detective". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on July 27, 2021. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ^ Liles, Jordan (June 21, 2021). "Disney Store on Oxford Street Is Only Remaining UK Location". Snopes. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ Sandoval, Ricardo (December 26, 1993). "Disney Enterprise Retail Splash". Chicago Tribune. San Francisco Examiner. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard (May 4, 1990). "Disney Stores: Magic in Retail?". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Vaughan, Vicki (December 19, 1985). "Disney Picks Paris Area For European Theme Park". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (April 20, 1992). "Voila! Disney Invades Europe. Will the French Resist?". Time. Archived from the original on August 1, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ "Advertisement: $53,279,000 The Biggest Animated Release in U.S. History". Variety. December 6, 1989. p. 19.

- ^ "Disney Says 'Mermaid' Swims To B.O. Record". Daily Variety. November 1, 1990. p. 6.

- ^ Stein, Benjamin (October 2, 1988). "Viewpoints: The new and successful Disney: Walt Disney Co. is on the rebound in a big way, and its shareholders are benefiting from the company's growth as much as are the officers--a real rarity in the corporate world". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Garrett, Martin (April 13, 2022). "The 10 Best Attractions at Disney's Hollywood Studios". Paste Magazine. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Butler & Russell 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Chilton, Louis (August 30, 2021). "Disney's attempt to buy The Muppets 'is probably what killed' Jim Henson, claims Frank Oz". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Stevenson, Richard (August 28, 1989). "Muppets Join Disney Menagerie". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Burr, Ty (May 16, 1997). "The Death of Jim Henson". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 10, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (October 27, 2003). "Cartoon Coffers - Top-Grossing Disney Animated Features at the Worldwide B.O." Variety. p. 6. Archived from the original on November 4, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "Ranking: The Disney Renaissance From Worst to Best". Time. November 17, 2014. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

{{cite magazine}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - ^ "A New Documentary Shines a Spotlight on the Lyricist Behind the Disney Renaissance". NPR. Morning Edition. August 6, 2020. Archived from the original on May 9, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Joanna, Robinson (April 20, 2018). "Inside the Tragedy and Triumph of Disney Genius Howard Ashman". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Allison, Austin (January 23, 2022). "Disney and Pixar's Top 5 Most Innovative Animation Technologies, Explained". Collider. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Rescuers Down Under (1990)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 12, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ "The Rescuers Down Under (1990)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Bettineger, Brendan (June 24, 2012). "Pixar by the Numbers - From Toy Story to Brave". Collider. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Disney To Launch New Record Division". Chicago Tribune. November 29, 1989. Archived from the original on November 24, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ "Hollywood Records". D23. Disney. Archived from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (November 14, 2019). "The Story of the 1991 Beauty and the Beast Screening That Changed Everything". Vulture. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 173.

- ^ Feinberg, Scott (March 23, 2022). "Beauty and the Beast and Its Unprecedented Oscar Run in 1992: "It Was a Giant Moment for Everyone"". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Brew, Simon (November 13, 2019). "Why Beauty and the Beast Remains Disney's Best Animated Film". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Spiegel, Josh (November 16, 2016). "25 years later, Beauty And The Beast remains Disney's best modern movie". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 24, 2022.

- ^ Joe, Lapointe (December 11, 1992). "Hockey; N.H.L. Is Going to Disneyland, and South Florida, Too". The New York Times. p. 7. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Aladdin box office info". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on February 15, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Sokol, Tony (February 13, 2020). "Aladdin Sequel in Development". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "The 65th Academy Awards (1993) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "1993 Grammy Award Winners". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Lior (May 21, 2019). ""Songs Are Like Love": Aladdin Songwriters Look Back on "A Whole New World"". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Bart, Peter (September 19, 2019). "Peter Bart: A Disney Deal Gone Wrong: How Mouse Money Fueled Harvey Weinstein's Alleged Predation As Miramax Mogul". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Rutherford 2011, p. 78.

- ^ "Disney president dies in helicopter crash". Tampa Bay Times. April 4, 1994. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "The Lion King (1994)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 13, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Richard, Natale (December 30, 1994). "The Movie Year: Hollywood Loses Its Middle Class: Box office: Blockbusters helped make it a record-setting year, but there was a rash of complete flops, and moderate successes seemed to disappear altogether". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "The 67th Academy Awards (1995) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "The Lion King (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on April 5, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Says His Resignation Bars Bonuses to Katzenberg". The New York Times. Reuters. May 18, 1996. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Hastings, Deborah (August 14, 1955). "From Mailroom to Mega-Agent: Michael Ovitz Becomes Disney President". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Thompson, Anne (August 25, 1995). "Michael Ovitz named President of Disney". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Rumors heat up on Disney-NBC deal". UPI. September 22, 1994. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Kathryn; John, Lippman (September 24, 1994). "Disney Said to End NBC Bid, Not Content With 49% Stake: Acquisition: The withdrawal may aid the position of Time Warner, which seeks a minor stake to avoid regulatory problems". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ a b Michael, Dresser (August 1, 1995). "A media giant is born Merger is biggest in entertainment industry's history Disney, Capital Cities/ABC merger". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 2, 2021. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "Pocahontas (1995)". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on October 5, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ "The 68th Academy Awards 1996". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Zorthian, Julia (November 19, 2015). "How Toy Story Changed Movie History". Time. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ King, Susan (September 30, 2015). "How 'Toy Story' changed the face of animation, taking off 'like an explosion'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "Disney's new tomorrowland: ABC". Tampa Bay Times. August 1, 1995. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ DiOrio, Carl (September 18, 2000). "Bain backing buyout of DIC". Variety. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Goldberg 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Michaelson, Judith (October 2, 1997). "For Kids' Ears, Mostly: Radio Disney says that its 5-week-old L.A. outlet on KTZN-AM is already a solid success". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Madej & Newton 2020, p. 147.

- ^ "The Hunchback of Notre Dame". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on June 10, 2003. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Farell, Rita K. (November 13, 2004). "Ovitz Fired for Management Style, Ex-Disney Director Testifies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ O'Neill, Ann W. (September 28, 1997). "The Court Files: Mickey's Masters Killed Fellow Cartoon Critter, Judge Rules". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2022.

- ^ Ahrens, Frank (April 16, 2003). "Disney Finds Buyer For Anaheim Angels". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Hernandez, Greg (May 15, 1996). "Anaheim Seals Disney Angels Deal". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ "Hercules (1997)". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on March 31, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Lohr, Steve (February 25, 1997). "Disney in 10-Year, 5-Film Deal With Pixar". The New York Times. p. 8. Archived from the original on July 1, 2022. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Prince, Rosa (March 21, 2012). "Richard Gere: Pretty Woman a 'Silly Romantic Comedy'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Pretty Woman (1990)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 15, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Sister Act (1992) - Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on July 24, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Con Air (1997)". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on March 4, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ a b "1998 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Eades, Mark (August 30, 2017). "A former Disney Imagineer's guide to Disney's Animal Kingdom". The Orange County Register. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Disney's Animal Kingdom opened 24 years ago today on Earth Day". Fox 35 Orlando. April 22, 2022. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "Mulan". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ "A Bug's Life". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Bicknell, Craig; Brekke, Dan (June 18, 1998). "Disney Buys into Infoseek". Wired. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Fredrick, John (June 18, 1998). "Disney buys Infoseek stake". CNN. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Dezern, Craig (February 20, 1994). "Disney Contemplating Creation Of Cruise Line". Orlando Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; June 2, 2016 suggested (help) - ^ "Company News; Disney to Start its Own Cruise Line by 1998". The New York Times. Bloomberg News. May 4, 1994. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2022.

- ^ Saunders 2013, pp. 76–78.

- ^ "Disney to acquire the rest of Infoseek, create Internet unit; Move comes amid effort to reverse slide in earnings; Cyberspace". The Baltimore Sun. Bloomberg News. July 13, 1999. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "GO Network premieres". CNN. January 12, 1999. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Tarzan". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Tarzan". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "The 72nd Academy Awards (2000) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ Crow, David (March 17, 2017). "The Disney Renaissance: The Rise & Fall of a Generational Touchstone". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Toy Story 2 (1999)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Toy Story 2". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on June 26, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Bernard, Weinraub (January 25, 2000). "Disney Names New President In Reshuffling". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Disney taps new No. 2". CNN. January 24, 2000. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Walt Disney Agrees to Sell DIC Entertainment". Los Angeles News. Bloomberg News. November 18, 2000. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 4, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Buys Fox Family Channel". CBS News. Associated Press. July 23, 2001. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Disney lays off 4,000 world wide". UPI. March 27, 2001. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Plans More Cutbacks As Chief Forecasts Rebound". The New York Times. Reuters. January 4, 2002. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Masunaga, Samantha (November 12, 2015). "From the Mighty Ducks to the Angels: Disney's track record with sports". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Holson, Laura (April 16, 2003). "Baseball; Disney Reaches a Deal For the Sale of the Angels". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 2, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ DiOrio, Carl (December 3, 2003). "Disney does $3 bil globally". Variety. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Roy Disney, ally quit Disney board". NBC News. Associated Press. December 1, 2003. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Disney's Eisner Rebuked in Shareholder Vote". ABC News. March 3, 2004. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Teather, David (March 4, 2004). "Disney shareholders force Eisner out of chairman's role". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Holson, Laura (March 10, 2004). "Former P. & G. Chief Named Disney Chairman". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Susman, Gary (February 18, 2004). "Disney buys the Muppets". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (November 2, 2020). "Disney's Muppets Problem: Can the Franchise Reckon With Its Boys' Club Culture?". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Susman, Gary (July 28, 2003). "Nemo becomes the top-grossing 'toon of all time". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Finding Nemo (2003)". The Numbers. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Holson, Laura (January 31, 2004). "Pixar to Find Its Own Way as Disney Partnership Ends". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 26, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Fritz, Ben (October 20, 2004). "Disney stores become a Children's Place". Variety. Archived from the original on July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ "Disney Finds Buyer for the Ducks". The New York Times. Associated Press. February 26, 2005. Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Verrier, Richard (July 9, 2005). "Feud at Disney Ends Quietly". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Ahrens, Frank (March 14, 2005). "Disney Chooses Successor to Chief Executive Eisner". The Washington Post. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ VanHoose, Benjamin (December 21, 2021). "Bob Iger Has 'No Interest in Running Another Company' After 15-Year Tenure as Disney CEO". People. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 9, 2022.

- ^ "Disney opens theme park in Hong Kong". NBC News. Associated Press. September 12, 2005. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Debruge, Peter (November 22, 2016). "Disney's Pixar Acquisition: Bob Iger's Bold Move That Reanimated a Studio". Variety. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Holton, Laura (January 25, 2006). "Disney Agrees to Acquire Pixar in a $7.4 Billion Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2016. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (September 5, 2020). "The Incredible True Story of Disney's Oswald the Lucky Rabbit". Collider. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Arnall, Dan (February 6, 2006). "Disney Merges ABC Radio with Citadel Broadcasting". ABC News. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Disney merging radio network with Citadel". NBC News. Associated Press. February 6, 2006. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ Romano, Aja (November 13, 2019). "High School Musical – and its ongoing cultural legacy – explained". Vox. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Desowitz, Bill (September 11, 2006). "Dead Man's Chest Gets $1 Billion Booty". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "High School Musical 2 : OMG! It's a cable ratings record". Variety. August 18, 2007. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "Kermit as Mogul, Farting Fozzie Bear: How Disney's Muppets Movie Has Purists Rattled". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Barnes, Brooks (September 18, 2008). "Fuzzy Renaissance". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ "Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on February 11, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (June 29, 2007). "Ratatouille Roasts Rivals, Die Hard #2; Michael Moore's Sicko Has Healthy Debut". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Goodman, Dean (June 29, 2008). "Disney's WALL-E wows box office". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Moody, Annemarie (February 22, 2009). "WALL-E Wins Oscar Best Animated Feature, La Maison Wins Best Animated Short". Animation World Magazine. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Turner, Mimi (December 8, 2008). "Disney to acquire rest of Jetix shares". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (July 10, 2009). "D23 at Comic-Con and beyond". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 24, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Chmielewski, Dawn C. (March 10, 2010). "Disneyland history event will replace D23 Expo this year". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Marc, Graser; Siegel, Tatiana (February 9, 2009). "Disney signs deal with DreamWorks". Variety. Archived from the original on October 8, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Barnes, Brooke; Cieply, Michael (February 9, 2009). "DreamWorks and Disney Agree to a Distribution Deal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Up". Box Office Mojo. IMDbPro. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- '^ "Pixar's Up wins best animated film Oscar". Reuters. March 7, 2010. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Turner, Mimi. "Disney unveils Disney XD". The Hollywood Reporter. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 15, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Thomasch, Paul; Gina, Keating (August 31, 2009). "Disney to acquire Marvel in $4 billion deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Kramer, Staci D. (April 30, 2009). "It's Official: Disney Joins News Corp., NBCU In Hulu; Deal Includes Some Cable Nets". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 4, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ "Roy E Disney dies in California". The Guardian. Associated Press. December 16, 2009. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 25, 2022.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (May 12, 2010). "Haim Saban Buys Back Mighty Morphin Power Rangers Franchise & Brings It to Nickelodeon and Nicktoons". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Fritz, Ben (May 13, 2010). "Haim Saban buys back Power Rangers". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ^ Horn, Heather (July 30, 2010). "Disney Sells Miramax, at Last". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.