Fish: Difference between revisions

→Culture: img |

→Shoaling and schooling: adapt materials from Teleost, see there for attrib. |

||

| Line 389: | Line 389: | ||

[[File:School of Pterocaesio chrysozona in Papua New Guinea 1.jpg|thumb|These [[goldband fusilier]]s are [[Shoaling and schooling|schooling]] because their swimming is synchronised.|alt=Photo of thousands of fish separated from each other by distances of {{convert|2|in}} or less]] |

[[File:School of Pterocaesio chrysozona in Papua New Guinea 1.jpg|thumb|These [[goldband fusilier]]s are [[Shoaling and schooling|schooling]] because their swimming is synchronised.|alt=Photo of thousands of fish separated from each other by distances of {{convert|2|in}} or less]] |

||

An assemblage of fish merely using some localised resource such as food or nesting sites is called an ''aggregation''. A ''shoal'' is a loosely organised group where each fish swims and forages independently but is attracted to other members of the group and adjusts its behaviour, such as swimming speed, so that it remains close to the other members of the group. A ''school'' is a much more tightly organised group, synchronising its swimming so that all fish move at the same speed and in the same direction |

An assemblage of fish merely using some localised resource such as food or nesting sites is called an ''aggregation''. A ''shoal'' is a loosely organised group where each fish swims and forages independently but is attracted to other members of the group and adjusts its behaviour, such as swimming speed, so that it remains close to the other members of the group. A ''school'' is a much more tightly organised group, synchronising its swimming so that all fish move at the same speed and in the same direction.{{sfn|Helfman|Collette|Facey|1997|p=375}} |

||

Schooling is sometimes an [[antipredator adaptation]], offering improved vigilance against predators. It is often more efficient to gather food by working as a group, and individual fish optimise their strategies by choosing to join or leave a shoal. When a predator has been noticed, prey fish respond defensively, resulting in collective shoal behaviours such as synchronised movements. Responses do not consist only of attempting to hide or flee; antipredator tactics include for example scattering and reassembling. Fish also aggregate in shoals to spawn.<ref>{{cite book |last=Pitcher |first=Tony J. |chapter=12. Functions of Shoaling Behaviour in Teleosts |title=The Behaviour of Teleost Fishes |publisher=Springer |year=1986 |pages=294–337 |doi=10.1007/978-1-4684-8261-4_12 |isbn=978-1-4684-8263-8}}</ref> |

|||

=== Communication === |

=== Communication === |

||

Revision as of 14:01, 4 February 2024

| Fish Temporal range: Middle Cambrian – Recent

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Diversity of various fish including sharks, stingrays, bony fish, jawless fish, and coelacanths. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Olfactores |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Groups included | |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

A fish (pl.: fish or fishes) is an aquatic, gill-bearing animal with a hard skull that lacks limbs with digits. This includes hagfish, lampreys, and both cartilaginous and bony fish. Approximately 95% of living fish species are ray-finned bony fish; around 99% of those are teleosts. As a group, if tetrapods are excluded, fish are paraphyletic and so do not form a taxonomic group.[1][2]

The earliest organisms that can be classified as fish were soft-bodied chordates that first appeared during the Cambrian period. Although they lacked a true spine, they possessed notochords which allowed them to be more agile than their invertebrate counterparts. Fish would continue to evolve through the Paleozoic era, diversifying into a wide variety of forms. Many fish of the Paleozoic developed external armor that protected them from predators. The first fish with jaws appeared in the Silurian period, after which many (such as sharks) became formidable marine predators rather than just the prey of arthropods.

Most fish are ectothermic ("cold-blooded"), allowing their body temperatures to vary as ambient temperatures change, though some of the large active swimmers like white shark and tuna can hold a higher core temperature.[3][4] Fish can acoustically communicate with each other, most often in the context of feeding, aggression or courtship.[5]

Fish are abundant in most bodies of water. They can be found in nearly all aquatic environments, from high mountain streams (e.g., char and gudgeon) to the abyssal and even hadal depths of the deepest oceans (e.g., cusk-eels and snailfish), although no species has yet been documented in the deepest 25% of the ocean.[6] With 34,300 described species, fish exhibit greater species diversity than any other group of vertebrates.[7]

Fish are an important resource for humans worldwide, especially as food. Commercial and subsistence fishers hunt fish in wild fisheries or farm them in ponds or in cages in the ocean (in aquaculture). They are also caught by recreational fishers, kept as pets, raised by fishkeepers, and exhibited in public aquaria. Fish have had a role in culture through the ages, serving as deities, religious symbols, and as the subjects of art, books and movies.

Etymology

The word fish is inherited from Proto-Germanic, and is related to the Latin piscis and Old Irish īasc, though the exact root is unknown; some authorities reconstruct a Proto-Indo-European root *peysk-, attested only in Italic, Celtic, and Germanic.[8][9][10][11]

Evolution

Fish, as vertebrata, developed as sister of the tunicata. As the tetrapods emerged deep within the fishes group, as sister of the lungfish, characteristics of fish are typically shared by tetrapods, including having vertebrae and a cranium.

![Drawing of animal with large mouth, long tail, very small dorsal fins, and pectoral fins that attach towards the bottom of the body, resembling lizard legs in scale and development.[12]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/ba/Dunkleosteus_terrelli_%28fossil_fish%29_%28Cleveland_Shale_Member%2C_Ohio_Shale%2C_Upper_Devonian%3B_Rocky_River_Valley%2C_Cleveland%2C_Ohio%2C_USA%29_21_%2834001200911%29.jpg/220px-Dunkleosteus_terrelli_%28fossil_fish%29_%28Cleveland_Shale_Member%2C_Ohio_Shale%2C_Upper_Devonian%3B_Rocky_River_Valley%2C_Cleveland%2C_Ohio%2C_USA%29_21_%2834001200911%29.jpg)

Early fish from the fossil record are represented by a group of small, jawless, armored fish known as ostracoderms. Jawless fish lineages are mostly extinct. An extant clade, the lampreys may approximate ancient pre-jawed fish. The first jaws are found in Placodermi fossils. They lacked distinct teeth, having instead the oral surfaces of their jaw plates modified to serve the various purposes of teeth. The diversity of jawed vertebrates may indicate the evolutionary advantage of a jawed mouth. It is unclear if the advantage of a hinged jaw is greater biting force, improved respiration, or a combination of factors.

Fish may have evolved from a creature similar to a coral-like sea squirt, whose larvae resemble primitive fish in important ways. The first ancestors of fish may have kept the larval form into adulthood (as some sea squirts do today).

Phylogeny

Fishes are a paraphyletic group: that is, any clade containing all fish also contains the tetrapods. The latter are not fish, though they include fish-shaped forms, such as Whales and Dolphins (see evolution of cetaceans) or the extinct ichthyosaurs, both of which convergently acquired a fish-like body shape due to secondary aquatic adaptation. In a cladistic sense, tetrapods are a subset of Osteichthyes.

...it is increasingly widely accepted that tetrapods, including ourselves, are simply modified bony fishes, and so we are comfortable with using the taxon Osteichthyes as a clade, which now includes all tetrapods...

The following cladogram shows clades – some with, some without extant relatives – that are traditionally considered as "fishes" (cyan line) and the tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates), which are mostly terrestrial. Extinct groups are marked with a dagger (†).

| Vertebrata/ |

|

"Fishes" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Craniata |

Taxonomy

Fishes are a paraphyletic group and for this reason, groups such as the class Pisces seen in older reference works are no longer used in formal classifications. Traditional classification divides fish into three extant classes, and with extinct forms sometimes classified within the tree, sometimes as their own classes:[16]

- Class Agnatha (jawless fish)

- Subclass Cyclostomata (hagfish and lampreys)

- Subclass Ostracodermi (armoured jawless fish) †

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish)

- Subclass Elasmobranchii (sharks and rays)

- Subclass Holocephali (chimaeras and extinct relatives)

- Class Placodermi (armoured fish) †

- Class Acanthodii ("spiny sharks", sometimes classified under Actinopterygii) †

- Superclass Osteichthyes (bony fish)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray finned fishes)

- Clade Sarcopterygii (lobe finned fishes, ancestors of tetrapods)

The above scheme is the one most commonly encountered in non-specialist and general works. Many of the above groups are paraphyletic, in that they have given rise to successive groups: Agnatha are ancestral to Placodermi, who again have given rise to Osteichthyes, as well as to Acanthodii, the ancestors of Chondrichthyes. With the arrival of phylogenetic nomenclature, the fishes has been split up into a more detailed scheme, with the following major groups:

- Class Myxini (hagfish)

- Class Pteraspidomorphi † (early jawless fish)

- Class Thelodonti †

- Class Anaspida †

- Class Petromyzontida or Hyperoartia

- Petromyzontidae (lampreys)

- Class Conodonta (conodonts) †

- Class Cephalaspidomorphi † (early jawless fish)

- (unranked) Galeaspida †

- (unranked) Pituriaspida †

- (unranked) Osteostraci †

- Infraphylum Gnathostomata (jawed vertebrates)

- Class Placodermi † (armoured fish)

- Class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish)

- Class Acanthodii † (spiny sharks)

- Superclass Osteichthyes (bony fish)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish)

- Subclass Chondrostei

- Order Acipenseriformes (sturgeons and paddlefishes)

- Order Polypteriformes (reedfishes and bichirs).

- Subclass Neopterygii

- Subclass Chondrostei

- Class Sarcopterygii (lobe-finned fish)

- Subclass Actinistia (coelacanths)

- Subclass Dipnoi (lungfish, sister group to the tetrapods)

- Class Actinopterygii (ray-finned fish)

† – indicates extinct taxon

Some palaeontologists contend that because Conodonta are chordates, they are primitive fish. For a fuller treatment of this taxonomy, see the vertebrate article.

The position of hagfish in the phylum Chordata is not settled. Phylogenetic research in 1998 and 1999 supported the idea that the hagfish and the lampreys form a natural group, the Cyclostomata, that is a sister group of the Gnathostomata.[17][18]

Fish account for more than half of vertebrate species. As of 2016, there are over 32,000 described species of bony fish, over 1,100 species of cartilaginous fish, and over 100 hagfish and lampreys. A third of these fall within the nine largest families; from largest to smallest, these are Cyprinidae, Gobiidae, Cichlidae, Characidae, Loricariidae, Balitoridae, Serranidae, Labridae, and Scorpaenidae. About 64 families are monotypic, containing only one species.[13]

Diversity

-

Agnatha

(Pacific hagfish) -

Chondrichthyes

(Horn shark) -

Actinopterygii

(Brown trout) -

Sarcopterygii

(Coelacanth)

The term "fish" most precisely describes any non-tetrapod craniate (i.e. an animal with a skull and in most cases a backbone) that has gills throughout life and whose limbs, if any, are in the shape of fins.[20] Unlike groupings such as birds or mammals, fish are not a single clade but a paraphyletic collection of taxa, including hagfishes, lampreys, sharks and rays, ray-finned fish, coelacanths, and lungfish.[21][22] Indeed, lungfish and coelacanths are closer relatives of tetrapods (such as mammals, birds, amphibians, etc.) than of other fish such as ray-finned fish or sharks, so the last common ancestor of all fish is also an ancestor to tetrapods. As paraphyletic groups are no longer recognised in modern systematic biology, the use of the term "fish" as a biological group must be avoided.

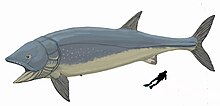

A typical fish is ectothermic, has a streamlined body for rapid swimming, extracts oxygen from water using gills or uses an accessory breathing organ to breathe atmospheric oxygen, has two sets of paired fins, usually one or two (rarely three) dorsal fins, an anal fin, and a tail fin, has jaws, has skin that is usually covered with scales, and lays eggs. Each criterion has exceptions. Tuna, swordfish, and some species of sharks show some warm-blooded adaptations – they can heat their bodies significantly above ambient water temperature.[21] Streamlining and swimming performance varies from fish such as tuna, salmon, and jacks that can cover 10–20 body-lengths per second to species such as eels and rays that swim no more than 0.5 body-lengths per second.[23] Many groups of freshwater fish extract oxygen from the air as well as from the water using a variety of different structures. Lungfish have paired lungs similar to those of tetrapods, gouramis have a structure called the labyrinth organ that performs a similar function, while many catfish, such as Corydoras extract oxygen via the intestine or stomach.[24] Body shape and the arrangement of the fins is highly variable, covering such seemingly un-fishlike forms as seahorses, pufferfish, anglerfish, and gulpers. Similarly, the surface of the skin may be naked (as in moray eels), or covered with scales of a variety of different types usually defined as placoid (typical of sharks and rays), cosmoid (fossil lungfish and coelacanths), ganoid (various fossil fish but also living gars and bichirs), cycloid, and ctenoid (these last two are found on most bony fish).[25] Fish range in size from the huge 16-metre (52 ft) whale shark to the tiny 8-millimetre (0.3 in) stout infantfish.

The diversity of living fish is unevenly distributed among the various groups, with teleosts making up the bulk of living fishes (96%).[26] The following cladogram[27] shows the evolutionary relationships of all groups of living fishes (with their respective diversity[26][28]) and the four-limbed vertebrates (tetrapods).

| Vertebrates |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ecology

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2024) |

Fish species are roughly divided equally between marine (oceanic) and freshwater ecosystems. Coral reefs in the Indo-Pacific constitute the center of diversity for marine fishes, whereas continental freshwater fishes are most diverse in large river basins of tropical rainforests, especially the Amazon, Congo, and Mekong basins. More than 5,600 fish species inhabit Neotropical freshwaters alone, such that Neotropical fishes represent about 10% of all vertebrate species on the Earth. Exceptionally rich sites in the Amazon basin, such as Cantão State Park, can contain more freshwater fish species than occur in all of Europe.[29]

The deepest living fish in the ocean so far found is the snailfish (Pseudoliparis belyaevi) which was filmed in the Izu-Ogasawara Trench off the coast of Japan at 8,336 meters in August 2022. The fish was filmed by a robotic lander as part of a scientific expedition funded by Victor Vescovo's Caladan Oceanic with the scientific team led by Professor Alan Jamieson of the University of Western Australia.[30]

A few fish live mostly on land or lay their eggs on land near water.[31] Mudskippers feed and interact with one another on mudflats and go underwater to hide in their burrows.[32] A single undescribed species of Phreatobius has been called a true "land fish" as this worm-like catfish strictly lives among waterlogged leaf litter.[33][34] Cavefish of multiple species live in underground lakes, underground rivers or aquifers.[35]

Anatomy and physiology

Respiration

Gills

Most fish exchange gases using gills on either side of the pharynx. Gills consist of threadlike structures called filaments. Each filament contains a capillary network that provides a large surface area for exchanging oxygen and carbon dioxide. Fish exchange gases by pulling oxygen-rich water through their mouths and pumping it over their gills. In some fish, capillary blood flows in the opposite direction to the water, causing countercurrent exchange. The gills push the oxygen-poor water out through openings in the sides of the pharynx. Some fish, like sharks and lampreys, possess multiple gill openings. However, bony fish have a single gill opening on each side. This opening is hidden beneath a protective bony cover called an operculum. Juvenile bichirs have external gills, a primitive feature shared with larval amphibians.

Air breathing

Fish from multiple groups can live out of the water for extended periods. Amphibious fish such as the mudskipper can move about on land and live in oxygen-depleted water. The skin of anguillid eels may absorb oxygen directly. The buccal cavity of the electric eel may breathe air. Catfish of the families Loricariidae, Callichthyidae, and Scoloplacidae absorb air through their digestive tracts.[36] Lungfish, with the exception of the Australian lungfish, and bichirs have paired lungs similar to those of tetrapods and must surface to gulp fresh air through the mouth and pass spent air out through the gills. Gar and bowfin have a vascularized swim bladder that functions in the same way. Loaches, trahiras, and many catfish breathe by passing air through the gut. Mudskippers breathe by absorbing oxygen across the skin (similar to frogs). Some fish have evolved accessory breathing organs: labyrinth fish such as gouramis and bettas have a labyrinth organ above the gills, while snakeheads, pikeheads, and Clariidae catfish have similar structures.

Some air-breathing fish are able to survive in damp burrows for weeks without water, entering a state of aestivation (summertime hibernation) until water returns.

Air breathing fish can be divided into obligate air breathers and facultative air breathers. Obligate air breathers, such as the African lungfish, must breathe air periodically or they suffocate. Facultative air breathers, such as the catfish Hypostomus plecostomus, only breathe air if they need to and will otherwise rely on their gills for oxygen. Most air breathing fish are facultative air breathers that avoid the energetic cost of rising to the surface and the fitness cost of exposure to surface predators.[36]

Circulation

Fish have a closed-loop circulatory system. The heart pumps the blood in a single loop throughout the body, with two chambers; for comparison, the mammal heart has two loops through the body and four chambers.[37] The first part is the sinus venosus, a thin-walled sac that collects blood from the fish's veins before allowing it to flow to the second part, the atrium, which is a large muscular chamber. The atrium serves as a one-way antechamber, sends blood to the third part, ventricle. The ventricle is another thick-walled, muscular chamber and it pumps the blood, first to the fourth part, bulbus arteriosus, a large tube, and then out of the heart. The bulbus arteriosus connects to the aorta, through which blood flows to the gills for oxygenation.

Digestion

Jaws allow fish to eat a wide variety of food, including plants and other organisms. Fish ingest food through the mouth and break it down in the esophagus. In the stomach, food is further digested and, in many fish, processed in finger-shaped pouches called pyloric caeca, which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients. Organs such as the liver and pancreas add enzymes and various chemicals as the food moves through the digestive tract. The intestine completes the process of digestion and nutrient absorption.

Excretion

Most fish release their nitrogenous wastes as ammonia. This may be excreted through the gills or filtered by the kidneys.

Saltwater fish tend to lose water by osmosis; their kidneys return water to the body, and produce a concentrated urine. The reverse happens in freshwater fish: they tend to gain water osmotically, and produce a dilute urine. Some fish have kidneys able to operate in both freshwater to saltwater.

Brain

Fish have small brains relative to body size compared with other vertebrates, typically one-fifteenth the brain mass of a similarly-sized bird or mammal.[38] However, some fish have relatively large brains, notably mormyrids and sharks, which have brains about as large for their body weight as birds and marsupials.[39] Fish brains are divided into several regions. At the front are the olfactory lobes, a pair of structures that receive and process signals from the nostrils via the two olfactory nerves.[38] The olfactory lobes are very large in fish that hunt primarily by smell, such as hagfish, sharks, and catfish. Behind the olfactory lobes is the two-lobed telencephalon, the structural equivalent to the cerebrum in higher vertebrates. In fish the telencephalon is concerned mostly with olfaction. Together these structures form the forebrain.[38] Connecting the forebrain to the midbrain is the diencephalon (in the diagram, this structure is below the optic lobes and consequently not visible). The diencephalon performs functions associated with hormones and homeostasis.[38] The pineal body lies just above the diencephalon. This structure detects light, maintains circadian rhythms, and controls color changes.[38] The midbrain (or mesencephalon) contains the two optic lobes. These are very large in species that hunt by sight, such as rainbow trout and cichlids.[38] The hindbrain (or metencephalon) is particularly involved in swimming and balance.[38] The cerebellum is a single-lobed structure that is typically the biggest part of the brain.[38] Hagfish and lampreys have relatively small cerebellae, while the mormyrid cerebellum is massive and apparently involved in their electrical sense.[38] The brain stem or myelencephalon is the brain's posterior.[38] As well as controlling some muscles and body organs, in bony fish at least, the brain stem governs respiration and osmoregulation.[38]

Sensory systems

The lateral line system is a network of sensors in the skin which detects gentle currents and vibrations, and senses the motion of nearby fish, whether predators or prey.[40] This can be considered both a sense of touch and of hearing. Blind cave fish navigate almost entirely through the sensations from their lateral line system.[41] Some fish, such as catfish and sharks, have the ampullae of Lorenzini, electroreceptors that detect weak electric currents on the order of millivolt.[42] Vision in fishes is an important sensory system. Fish eyes are similar to those of terrestrial vertebrates like birds and mammals, but have a more spherical lens. Their retinas generally have both rods and cones (for scotopic and photopic vision); most species have colour vision. Some fish can see ultraviolet, while others can see polarized light. Amongst jawless fish, the lamprey has well-developed eyes, while the hagfish has only primitive eyespots.[43] Hearing too is an important sensory system in fish. Fish sense sound using their lateral lines and otoliths in their ears, inside their heads. Some can detect sound through the swim bladder.[44] Some fish, including salmon, are capable of magnetoreception; when the axis of a magnetic field is changed around a circular tank of young fish, they reorient themselves in line with the field.[45][46] The mechanism of fish magnetoreception remains unknown;[47] experiments in birds imply a quantum radical pair mechanism.[48]

Cognition

The cognitive capacities of fish include self-awareness, as seen in mirror tests. Manta rays and wrasses placed in front of a mirror repeatedly check whether their reflection's behavior mimics their body movement.[49][50][51] Choerodon wrasse, archerfish, and Atlantic cod can solve problems and invent tools.[52] The monogamous cichlid Amatitlania siquia exhibits pessimistic behavior when prevented from being with its partner.[53] Fish orient themselves using landmarks; they may use mental maps based on multiple landmarks. Fish behavior in mazes reveals that they possess spatial memory and visual discrimination.[54] Fish have pain and fear responses; toadfish grunt when electrically shocked and over time come to grunt at the mere sight of an electrode.[55] Rainbow trout rock their bodies and rub their lips when injected with bee venom and acetic acid, apparently attempting to relieve pain.[56][57] The wrasse's neurons fired in a pattern resembling human neuronal patterns.[57] The claims have been called flawed as they do not prove that fish possess conscious awareness, especially not human-like awareness,[58] and their brains are very different.[59]

Locomotion

Most fish move by alternately contracting paired sets of muscles on either side of the backbone. These contractions form S-shaped curves that move down the body. As each curve reaches the back fin, backward force is applied to the water, and in conjunction with the fins, moves the fish forward. The fish's fins function like an airplane's flaps. Fins also increase the tail's surface area, increasing speed.[60]

The streamlined body of the fish decreases the amount of friction from the water. Since body tissue is denser than water, fish must compensate for the difference or they will sink. Many bony fish have an internal organ called a swim bladder that adjusts their buoyancy through manipulation of gases. The scales of fish originate from the mesoderm (skin); they may be similar in structure to teeth.

Endothermy

Although most fish are exclusively ectothermic, there are exceptions. The only known bony fishes (infraclass Teleostei) that exhibit endothermy are in the suborder Scombroidei – which includes the billfishes, tunas, and the butterfly kingfish, a basal species of mackerel[61] – and also the opah. The opah, a lampriform, was demonstrated in 2015 to use "whole-body endothermy", generating heat with its swimming muscles to warm its body while countercurrent exchange (as in respiration) minimizes heat loss.[62] It is able to actively hunt prey such as squid and swim for long distances due to the ability to warm its entire body, including its heart,[63] which is a trait typically found only in mammals and birds (in the form of homeothermy). In the cartilaginous fishes (class Chondrichthyes), sharks of the families Lamnidae (porbeagle, mackerel, salmon, and great white sharks) and Alopiidae (thresher sharks) exhibit endothermy. The degree of endothermy varies from the billfishes, which warm only their eyes and brain, to the bluefin tuna and the porbeagle shark, which maintain body temperatures in excess of 20 °C (68 °F) above ambient water temperatures.[61]

Endothermy, though metabolically costly, is thought to provide advantages such as increased muscle strength, higher rates of central nervous system processing, and higher rates of digestion.

Reproduction

The primary reproductive organs are testicles and ovaries. In most species, gonads are paired organs of similar size, which can be partially or totally fused.[64] Some fish have secondary organs that increase reproductive fitness.

In terms of spermatogonia distribution, the structure of teleosts testes has two types: in the most common, spermatogonia occur all along the seminiferous tubules, while in atherinomorph fish they are confined to the distal portion of these structures. Fish can present cystic or semi-cystic spermatogenesis in relation to the release phase of germ cells in cysts to the seminiferous tubules lumen.[64]

Fish ovaries may be of three types: gymnovarian, secondary gymnovarian or cystovarian. In the first type, the oocytes are released directly into the coelomic cavity and then enter the ostium, then through the oviduct and are eliminated. Secondary gymnovarian ovaries shed ova into the coelom from which they go directly into the oviduct. In the third type, the oocytes are conveyed to the exterior through the oviduct.[65] Gymnovaries are the primitive condition found in lungfish, sturgeon, and bowfin. Cystovaries characterize most teleosts, where the ovary lumen has continuity with the oviduct.[64] Secondary gymnovaries are found in salmonids and a few other teleosts.

Oogonia development in teleosts fish varies according to the group, and the determination of oogenesis dynamics allows the understanding of maturation and fertilization processes. Changes in the nucleus, ooplasm, and the surrounding layers characterize the oocyte maturation process.[64] Postovulatory follicles are structures formed after oocyte release; they do not have endocrine function, present a wide irregular lumen, and are rapidly reabsorbed in a process involving the apoptosis of follicular cells. A degenerative process called follicular atresia reabsorbs vitellogenic oocytes not spawned. This process can also occur, but less frequently, in oocytes in other development stages.[64]

Some fish, like the California sheephead, are hermaphrodites, having both testes and ovaries either at different phases in their life cycle or, as in hamlets, have them simultaneously.

Over 97% of fish are oviparous,[66] that is, the eggs develop outside the mother's body. Examples of oviparous fish include salmon, goldfish, cichlids, tuna, and eels. In the majority of these species, fertilisation takes place outside the mother's body, with the male and female fish shedding their gametes into the surrounding water. However, a few oviparous fish practice internal fertilization, with the male using some sort of intromittent organ to deliver sperm into the genital opening of the female, most notably the oviparous sharks, such as the horn shark, and oviparous rays, such as skates. In these cases, the male is equipped with a pair of modified pelvic fins known as claspers.

Marine fish can produce high numbers of eggs which are often released into the open water column. The eggs have an average diameter of 1 millimetre (0.04 in).

-

Egg of lamprey

-

Egg of catshark (mermaids' purse)

-

Egg of bullhead shark

-

Egg of chimaera

The newly hatched young of oviparous fish are called larvae. They are usually poorly formed, carry a large yolk sac (for nourishment), and do not resemble juvenile or adult fish. The larval period in oviparous fish is usually only someweeks, and larvae rapidly grow and change in structure to become juveniles. During this transition, larvae must switch from their yolk sac to feeding on zooplankton prey, a process which depends on typically inadequate zooplankton density, starving many larvae.

In ovoviviparous fish the eggs develop inside the mother's body after internal fertilization but receive little or no nourishment directly from the mother, depending instead on the yolk. Each embryo develops in its own egg. Familiar examples of ovoviviparous fish include guppies, angel sharks, and coelacanths.

Some species of fish are viviparous. In such species the mother retains the eggs and nourishes the embryos. Typically, viviparous fish have a structure analogous to the placenta seen in mammals connecting the mother's blood supply with that of the embryo. Examples of viviparous fish include the surf-perches, splitfins, and lemon shark. Some viviparous fish exhibit oophagy, in which the developing embryos eat other eggs produced by the mother. This has been observed primarily among sharks, such as the shortfin mako and porbeagle, but is known for a few bony fish as well, such as the halfbeak Nomorhamphus ebrardtii.[67] Intrauterine cannibalism is an even more unusual mode of vivipary, in which the largest embryos eat weaker and smaller siblings. This behavior is also most commonly found among sharks, such as the grey nurse shark, but has also been reported for Nomorhamphus ebrardtii.[67]

Behavior

Shoaling and schooling

An assemblage of fish merely using some localised resource such as food or nesting sites is called an aggregation. A shoal is a loosely organised group where each fish swims and forages independently but is attracted to other members of the group and adjusts its behaviour, such as swimming speed, so that it remains close to the other members of the group. A school is a much more tightly organised group, synchronising its swimming so that all fish move at the same speed and in the same direction.[68] Schooling is sometimes an antipredator adaptation, offering improved vigilance against predators. It is often more efficient to gather food by working as a group, and individual fish optimise their strategies by choosing to join or leave a shoal. When a predator has been noticed, prey fish respond defensively, resulting in collective shoal behaviours such as synchronised movements. Responses do not consist only of attempting to hide or flee; antipredator tactics include for example scattering and reassembling. Fish also aggregate in shoals to spawn.[69]

Communication

Fish communicate by transmitting sounds, acoustic signals, to each other. This is most often in the context of feeding, aggression or courtship.[5] The sounds emitted vary with the species and stimulus involved. Fish can produce either stridulatory sounds by moving components of the skeletal system, or can produce non-stridulatory sounds by manipulating specialized organs such as the swimbladder.[70]

Some fish produce sounds by rubbing or grinding their bones together. These sounds are stridulatory. In Haemulon flavolineatum, the French grunt fish, as it produces a grunting noise by grinding its teeth together, especially when in distress. The grunts are at a frequency of around 700 Hz, and last approximately 47 milliseconds.[70] The longsnout seahorse, Hippocampus reidi produces two categories of sounds, 'clicks' and 'growls', by rubbing their coronet bone across the grooved section of their neurocranium.[71] Clicks are produced during courtship and feeding, and the frequencies of clicks were within the range of 50 Hz-800 Hz. The frequencies are at the higher end of the range during spawning, when the female and male fishes were less than fifteen centimeters apart. Growls are produced when the H. reidi are stressed. The 'growl' sounds consist of a series of sound pulses and are emitted simultaneously with body vibrations.[72]

Some fish species create noise by engaging specialized muscles that contract and cause swimbladder vibrations. Oyster toadfish produce loud grunts by contracting sonic muscles along the sides of the swim bladder.[73] Female and male toadfishes emit short-duration grunts, often as a fright response.[74] In addition to short-duration grunts, male toadfishes produce "boat whistle calls".[75] These calls are longer in duration, lower in frequency, and are primarily used to attract mates.[75] The sounds emitted by the O. tao have frequency range of 140 Hz to 260 Hz.[75] The frequencies of the calls depend on the rate at which the sonic muscles contract.[76][73]

The red drum, Sciaenops ocellatus, produces drumming sounds by vibrating its swimbladder. Vibrations are caused by the rapid contraction of sonic muscles that surround the dorsal aspect of the swimbladder. These vibrations result in repeated sounds with frequencies from 100 to >200 Hz. S. ocellatus produces different calls depending on the stimuli involved, such as courtship or a predator's attack. Females do not produce sounds, and lack sound-producing (sonic) muscles.[77]

Defense against disease

Like other animals, fish suffer from diseases and parasites. To prevent disease they have a variety of defenses. Non-specific defenses include the skin and scales, as well as the mucus layer secreted by the epidermis that traps and inhibits the growth of microorganisms. If pathogens breach these defenses, fish can develop an inflammatory response that increases blood flow to the infected region and delivers white blood cells that attempt to destroy pathogens. Specific defenses respond to particular pathogens recognised by the fish's body, i.e., an immune response.[78]

Some species use cleaner fish to remove external parasites. The best known of these are the bluestreak cleaner wrasses of coral reefs in the Indian and Pacific oceans. These small fish maintain cleaning stations where other fish congregate and perform specific movements to attract the attention of the cleaners.[79] Cleaning behaviors have been observed in a number of fish groups, including an interesting case between two cichlids of the same genus, Etroplus maculatus, the cleaner, and the much larger Etroplus suratensis.[80]

Immune organs vary by type of fish.[81] In the jawless fish (lampreys and hagfish), true lymphoid organs are absent. These fish rely on regions of lymphoid tissue within other organs to produce immune cells. For example, erythrocytes, macrophages and plasma cells are produced in the anterior kidney (or pronephros) and some areas of the gut (where granulocytes mature.) They resemble primitive bone marrow in hagfish. Cartilaginous fish (sharks and rays) have a more advanced immune system. They have three specialized organs that are unique to Chondrichthyes; the epigonal organs (lymphoid tissue similar to mammalian bone) that surround the gonads, the Leydig's organ within the walls of their esophagus, and a spiral valve in their intestine. These organs house typical immune cells (granulocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells). They also possess an identifiable thymus and a well-developed spleen (their most important immune organ) where various lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages develop and are stored. Chondrostean fish (sturgeons, paddlefish, and bichirs) possess a major site for the production of granulocytes within a mass that is associated with the meninges (membranes surrounding the central nervous system.) Their heart is frequently covered with tissue that contains lymphocytes, reticular cells and a small number of macrophages. The chondrostean kidney is an important hemopoietic organ; where erythrocytes, granulocytes, lymphocytes and macrophages develop.

Like chondrostean fish, the major immune tissues of bony fish (or teleostei) include the kidney (especially the anterior kidney), which houses many different immune cells.[82] In addition, teleost fish possess a thymus, spleen and scattered immune areas within mucosal tissues (e.g. in the skin, gills, gut and gonads). Much like the mammalian immune system, teleost erythrocytes, neutrophils and granulocytes are believed to reside in the spleen whereas lymphocytes are the major cell type found in the thymus.[83][84] In 2006, a lymphatic system similar to that in mammals was described in one species of teleost fish, the zebrafish. Although not confirmed as yet, this system presumably will be where naive (unstimulated) T cells accumulate while waiting to encounter an antigen.[85]

B and T lymphocytes bearing immunoglobulins and T cell receptors, respectively, are found in all jawed fishes. Indeed, the adaptive immune system as a whole evolved in an ancestor of all jawed vertebrates.[86]

Conservation

The 2006 IUCN Red List names 1,173 fish species that are threatened with extinction.[87] Included are species such as Atlantic cod,[88] Devil's Hole pupfish,[89] coelacanths,[90] and great white sharks.[91] Because fish live underwater they are more difficult to study than terrestrial animals and plants, and information about fish populations is often lacking. However, freshwater fish seem particularly threatened because they often live in relatively small water bodies. For example, the Devil's Hole pupfish occupies only a single 3 by 6 metres (10 by 20 ft) pool.[92]

Overfishing

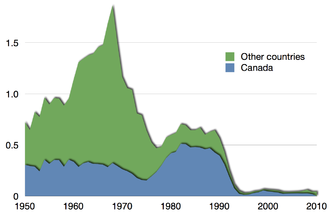

Overfishing is a major threat to edible fish such as cod and tuna.[93][94] Overfishing eventually causes population (known as stock) collapse because the survivors cannot produce enough young to replace those removed. Such commercial extinction does not mean that the species is extinct, merely that it can no longer sustain a fishery. A well-studied example of fishery collapse is the Pacific sardine Sadinops sagax caerulues fishery off the California coast. From a 1937 peak of 790,000 long tons (800,000 t) the catch steadily declined to only 24,000 long tons (24,000 t) in 1968, after which the fishery was no longer economically viable.[95]

Fisheries scientists and the fishing industry have different views on the resiliency of fisheries to intensive fishing. In places such as Scotland, Newfoundland, and Alaska the fishing industry is a major employer, so governments are predisposed to support it.[96][97] On the other hand, scientists and conservationists push for stringent protection, warning that many stocks could be wiped out within fifty years.[98][99]

Habitat destruction

A key stress on both freshwater and marine ecosystems is habitat degradation including water pollution, the building of dams, removal of water for use by humans, and the introduction of exotic species.[100] An example of a fish that has become endangered because of habitat change is the pallid sturgeon, a North American freshwater fish that lives in rivers damaged by human activity.[101]

Exotic species

Introduction of non-native species occurs in many habitats. The Mediterranean Sea has become a major 'hotspot' of exotic invaders since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. A thousand marine species of all sorts – fishes, seaweeds, invertebrates – originating from the Red Sea and more broadly from the Indo-Pacific have crossed the Canal from south to north to settle in the eastern Mediterranean Basin. Nowadays many of these tropical migrants, also called Lessepsian species, have extended their range towards the west, obviously favoured by the general warming of the Mediterranean. The resulting change in biodiversity is without precedent in human memory and is accelerating: a long-term cross-Basin survey engaged by the Mediterranean Science Commission recently documented that in just twenty years, from 2001 till 2021, no less than 107 alien fish species have reached the Mediterranean from both the tropical Atlantic and the Red Sea, which is more than the total recorded during the whole 130 preceding years.[102]

Another mode of introduction for marine species is transport across thousands of kms on ship hulls or in ballast waters. Examples abound of marine organisms being transported in ballast water, among them the invasive comb jelly Mnemiopsis leidyi, the dangerous bacterium Vibrio cholerae, or the fouling zebra mussel. The Mediterranean and Black Seas, with their high volume shipping from exotic harbors, are particularly impacted by this problem.[103]

Deliberate introductions of species with market potential are another frequent vector: one of the best studied examples is the introduction of the Nile perch into Lake Victoria in the 1960s. Nile perch gradually exterminated the lake's 500 endemic cichlid species. Some of them now survive in captive breeding programmes, but others are probably extinct.[104] Carp, snakeheads,[105] tilapia, European perch, brown trout, rainbow trout, and sea lampreys are other examples of fish that have caused problems by being introduced into alien environments.

Importance to humans

Economic

Throughout history, humans have used fish as a food source for dietary protein. Historically and today, most fish harvested for human consumption has come by means of catching wild fish. However, fish farming, which has been practiced since about 3,500 BCE in ancient China,[106] is becoming increasingly important in many nations. Overall, about one-sixth of the world's protein is estimated to be provided by fish.[107] That proportion is considerably elevated in some developing nations and regions heavily dependent on seafood. In a similar manner, fish have been tied to primary industry and associated food, feed, pharmaceutical production and service industries.

Catching fish for the purpose of food or sport is known as fishing, while the organized effort by humans to catch fish is called a fishery (which also describes the area where such enterprise operates). Fisheries are a huge global business and provide income for millions of people.[107] The annual yield from all fisheries worldwide is about 154 million tons,[108] with popular species including herring, cod, anchovy, tuna, flounder, and salmon. However, the term fishery is broadly applied, and includes more organisms than just fish, such as mollusks and crustaceans, which are often collectively called "shellfish" when used as food.

The Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) has a guide[109] to which fish are healthiest (or least safe) to eat, given the state of pollution in today's world, and also which fish are obtained in a way that does not lead towards extinction of the fish.

Recreation

Fish have been recognized as a source of beauty for almost as long as used for food, appearing in cave art, being raised as ornamental fish in ponds, and displayed in aquariums in homes, offices, or public settings. Recreational fishing is fishing primarily for pleasure or competition; it can be contrasted with commercial fishing, which is fishing for profit, or artisanal fishing, which is fishing primarily for food. The most common form of recreational fishing is done with a rod, reel, line, hooks, and any one of a wide range of baits. Recreational fishing is particularly popular in North America and Europe and state, provincial, and federal government agencies actively management target fish species.[110][111]

Culture

Fish themes have symbolic significance in many religions. In ancient Mesopotamia, fish offerings were made to the gods from the very earliest times.[112] Fish were also a major symbol of Enki, the god of water.[112] Fish frequently appear as filling motifs in cylinder seals from the Old Babylonian (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC) and Neo-Assyrian (911–609 BC) periods.[112] Starting during the Kassite Period (c. 1600 BC – c. 1155 BC) and lasting until the early Persian Period (550–30 BC), healers and exorcists dressed in ritual garb resembling the bodies of fish.[112] During the Seleucid Period (312–63 BC), the legendary Babylonian culture hero Oannes, described by Berossus, was said to have dressed in the skin of a fish.[112] Fish were sacred to the Syrian goddess Atargatis[113] and, during her festivals, only her priests were permitted to eat them.[113]

In the Book of Jonah, the central figure, a prophet named Jonah, is swallowed by a giant fish after being thrown overboard by the crew of the ship he is travelling on.[114] Early Christians used the ichthys, a symbol of a fish, to represent Jesus,[113][115] because the Greek word for fish, ΙΧΘΥΣ Ichthys, could be used as an acronym for "Ίησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ" (Iesous Christos, Theou Huios, Soter), meaning "Jesus Christ, Son of God, Saviour".[113][115]

Among the deities said to take the form of a fish are Ika-Roa of the Polynesians, Dagon of various ancient Semitic peoples, the shark-gods of Hawaiʻi and Matsya of the Hindus. The astrological symbol Pisces is based on a constellation of the same name, but there is also a second fish constellation in the night sky, Piscis Austrinus.[116]

Fish feature prominently in art, in movies such as Finding Nemo and books such as The Old Man and the Sea. Large fish, particularly sharks, have frequently been the subject of horror movies and thrillers, notably the novel Jaws, in turn parodied in Shark Tale and Snakehead Terror. Piranhas are shown in a similar light to sharks in films such as Piranha; however, contrary to popular belief, the red-bellied piranha is actually a generally timid scavenger species that is unlikely to harm humans.[117]

-

The Fishmonger's Shop, Bartolomeo Passerotti, 1580s

-

Goldfish by Henri Matisse, 1912

See also

- Catch and release

- Deep sea fish

- Fish acute toxicity syndrome

- Fish anatomy

- Fish development

- Forage fish

- Ichthyology

- List of fish common names

- List of fish families

- Marine biology

- Marine vertebrates

- Mercury in fish

- Otolith (Bone used for determining the age of a fish)

- Pregnancy (fish)

- Seafood

- Shoaling and schooling

- Walking fish

References

- ^ "Zoology" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Greene, Harry W. (1 January 1998). "We are primates and we are fish: Teaching monophyletic organismal biology". Integrative Biology. 1 (3): 108–111. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6602(1998)1:3<108::aid-inbi5>3.0.co;2-t. ISSN 1520-6602.

- ^ Goldman, K.J. (1997). "Regulation of body temperature in the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias". Journal of Comparative Physiology. B Biochemical Systemic and Environmental Physiology. 167 (6): 423–429. doi:10.1007/s003600050092. S2CID 28082417. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Carey, F.G.; Lawson, K.D. (February 1973). "Temperature regulation in free-swimming bluefin tuna". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 44 (2): 375–392. doi:10.1016/0300-9629(73)90490-8. PMID 4145757.

- ^ a b Weinmann, S.R.; Black, A.N.; Richter, M.L.; Itzkowitz, M.; Burger, R.M. (February 2017). "Territorial vocalization in sympatric damselfish: acoustic characteristics and intruder discrimination". Bioacoustics. 27 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1080/09524622.2017.1286263. S2CID 89625932.

- ^ Yancey, P.H.; Gerringer, M.E.; Drazen, J.C.; Rowden, A.A.; Jamieson, A. (2014). "Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111 (12): 4461–4465. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.4461Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1322003111. PMC 3970477. PMID 24591588.

- ^ "FishBase Search". FishBase. March 2020. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ "DWDS – Digitales Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache". DWDS (in German). Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Winfred Philipp Lehmann, Helen-Jo J. Hewitt, Sigmund Feist, A Gothic etymological dictionary, 1986, s.v. fisks p. 118

- ^ "fish, n.1", OED Online, Oxford University Press, archived from the original on 17 March 2023, retrieved 21 January 2023

- ^ Carl Darling Buck, A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages, 1949, s.v., section 3.65, p. 184

- ^ "Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever". Smh.com.au. 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ a b Nelson, Joseph S. (2016). "Taxonomic Diversity". Fishes of the World. John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- ^

Giles, Sam; Friedman, Matt; Brazeau, Martin D. (12 January 2015). "Osteichthyan-like cranial conditions in an Early Devonian stem gnathostome". Nature. 520 (7545): 82–85. Bibcode:2015Natur.520...82G. doi:10.1038/nature14065. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 5536226. PMID 25581798.

Giles, Sam; Friedman, Matt; Brazeau, Martin D. (12 January 2015). "Osteichthyan-like cranial conditions in an Early Devonian stem gnathostome". Nature. 520 (7545): 82–85. Bibcode:2015Natur.520...82G. doi:10.1038/nature14065. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 5536226. PMID 25581798.

- ^ Davis, S; Finarelli, J; Coates, M (2012). "Acanthodes and shark-like conditions in the last common ancestor of modern gnathostomes". Nature. 486 (7402): 247–250. Bibcode:2012Natur.486..247D. doi:10.1038/nature11080. PMID 22699617. S2CID 4304310.

- ^ Benton, M.J. (1998) The quality of the fossil record of vertebrates. pp. 269–303, in Donovan, S.K. and Paul, C.R.C. (eds), The adequacy of the fossil record, Fig. 2. Wiley, New York, 312 pp.

- ^ Shigehiro Kuraku, Daisuke Hoshiyama, Kazutaka Katoh, Hiroshi Suga, Takashi Miyata (1999) Monophyly of Lampreys and Hagfishes Supported by Nuclear DNA–Coded Genes J Mol Evol (1999) 49:729–735

- ^ J. Mallatt, J. Sullivan (1998) 28S and 18S rDNA sequences support the monophyly of lampreys and hagfishes Molecular Biology and Evolution V 15, Issue 12, pp. 1706–1718

- ^ Goda, M.; R. Fujii (2009). "Blue Chromatophores in Two Species of Callionymid Fish". Zoological Science. 12 (6): 811–813. doi:10.2108/zsj.12.811. S2CID 86385679.

- ^ Nelson 2006, p. 2.

- ^ a b Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Tree of life web project – Chordates Archived 24 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 103.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, pp. 53–57.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, pp. 33–36.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

autowas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Friedman, Matt; Sallan, Lauren Cole (June 2012). "Five hundred million years of extinczion and recovery: A Phanerozoic survey of large-scale diversity patterns in fishes". Palaeontology. 55 (4): 707–742. Bibcode:2012Palgy..55..707F. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2012.01165.x. S2CID 59423401.

- ^ Brownstein; et al. (27 July 2022). "Hidden species diversity in a living fossil vertebrate" (PDF). Biology Letters. 18 (11). bioRxiv 10.1101/2022.07.25.500718. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0395. PMC 9709656. PMID 36448369. S2CID 251162051.

- ^ "Estudo das Espécies Ícticas do Parque Estadual do Cantão". central3.to.gov.br. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ "Deepest ever fish caught on camera off Japan". BBC News. 1 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Martin, K.L.M. (2014). Beach-Spawning Fishes: Reproduction in an Endangered Ecosystem. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4822-0797-2.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2006). "Periophthalmus barbarus" in FishBase. November 2006 version.

- ^ Planet Catfish. "Cat-eLog: Heptapteridae: Phreatobius: Phreatobius sp. (1)". Planet Catfish. Archived from the original on 23 October 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2006.

- ^ Henderson, P.A.; Walker, I. (1990). "Spatial organization and population density of the fish community of the litter banks within a central Amazonian blackwater stream". Journal of Fish Biology. 37 (3): 401–411. Bibcode:1990JFBio..37..401H. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1990.tb05871.x.

- ^ Helfman, G.S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-55963-595-0.

- ^ a b Armbruster, Jonathan W. (1998). "Modifications of the Digestive Tract for Holding Air in Loricariid and Scoloplacid Catfishes" (PDF). Copeia. 1998 (3): 663–675. doi:10.2307/1447796. JSTOR 1447796. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- ^ Setaro, John F. (1999). Circulatory System. Microsoft Encarta 99.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 191.

- ^ Orr, James (1999). Fish. Microsoft Encarta 99. ISBN 978-0-8114-2346-5.

- ^ Godfrey-Smith, Peter (2020). "Kingfish". Metazoa. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 9780374207946.

- ^ Albert, J.S., and W.G.R. Crampton. 2005. "Electroreception and electrogenesis". pp. 431–472 in The Physiology of Fishes, 3rd ed. D.H. Evans and J.B. Claiborne (eds.). CRC Press.

- ^ Campbell, Neil A.; Reece, Jane B. (2005). Biology (Seventh ed.). San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings.

- ^ Hawkins, A. D. (1981). "6. The Hearing Abilities of Fish". In Tavolga, William N.; Popper, Arthur N.; Fay, Richard R. (eds.). Hearing and Sound Communication in Fishes. Springer. pp. 109–138. ISBN 978-1-4615-7188-9.

- ^ Quinn, Thomas P. (1980). "Evidence for celestial and magnetic compass orientation in lake migrating sockeye salmon fry". Journal of Comparative Physiology A. 137 (3): 243–248. doi:10.1007/bf00657119. S2CID 44036559.

- ^ Taylor, P. B. (May 1986). "Experimental evidence for geomagnetic orientation in juvenile salmon, Oncorhynchus tschawytscha Walbaum". Journal of Fish Biology. 28 (5): 607–623. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1986.tb05196.x.

- ^ Formicki, Krzysztof; Korzelecka‐Orkisz, Agata; Tański, Adam (2019). "Magnetoreception in fish". Journal of Fish Biology. 95 (1): 73–91. doi:10.1111/jfb.13998. ISSN 0022-1112.

- ^ Hore, Peter J.; Mouritsen, Henrik (April 2022). "The Quantum Nature of Bird Migration". Scientific American: 24–29.

- ^ Ari, Csilla; D’Agostino, Dominic P. (1 May 2016). "Contingency checking and self-directed behaviors in giant manta rays: Do elasmobranchs have self-awareness?". Journal of Ethology. 34 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1007/s10164-016-0462-z. ISSN 1439-5444. S2CID 254134775. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Kohda, Masanori; Hotta, Takashi; Takeyama, Tomohiro; Awata, Satoshi; Tanaka, Hirokazu; Asai, Jun-ya; Jordan, L. Alex (21 August 2018). "Cleaner wrasse pass the mark test. What are the implications for consciousness and self-awareness testing in animals?". PLOS Biology: 397067. doi:10.1101/397067. S2CID 91375693. Archived from the original on 23 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ "Scientists find some fish can 'recognise themselves' in mirror". the Guardian. 7 February 2019. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 January 2023.

- ^ Fishes Use Problem-Solving and Invent Tools Archived 17 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine- article at Scientific American Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Laubu, Chloé; Louâpre, Philippe; Dechaume-Moncharmont, François-Xavier (2019). "Pair-bonding influences affective state in a monogamous fish species". Proc. R. Soc. B. 286 (1904). 20190760. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.0760. PMC 6571461. PMID 31185864.

- ^ Sciences, Journal of Undergraduate Life. "Appropriate maze methodology to study learning in fish" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 28 May 2009.

- ^ Dunayer, Joan, "Fish: Sensitivity Beyond the Captor's Grasp," The Animals' Agenda, July/August 1991, pp. 12–18

- ^ Kirby, Alex (30 April 2003). "Fish do feel pain, scientists say". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York City: Scribner. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-7432-4769-6.

- ^ "Rose, J.D. 2003. A Critique of the paper: "Do fish have nociceptors: Evidence for the evolution of a vertebrate sensory system"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Rose, James D. (2002). "Do Fish Feel Pain?". Archived from the original on 20 January 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- ^ Sfakiotakis, M.; Lane, D. M.; Davies, J. B. C. (1999). "Review of Fish Swimming Modes for Aquatic Locomotion" (PDF). IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering. 24 (2): 237–252. Bibcode:1999IJOE...24..237S. doi:10.1109/48.757275. S2CID 17226211. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013.

- ^ a b Block, BA; Finnerty, JR (1993). "Endothermy in fishes: a phylogenetic analysis of constraints, predispositions, and selection pressures" (PDF). Environmental Biology of Fishes. 40 (3): 283–302. doi:10.1007/BF00002518. S2CID 28644501. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ Wegner, Nicholas C.; Snodgrass, Owyn E.; Dewar, Heidi; Hyde, John R. (15 May 2015). "Whole-body endothermy in a mesopelagic fish, the opah, Lampris guttatus". Science. 348 (6236): 786–789. Bibcode:2015Sci...348..786W. doi:10.1126/science.aaa8902. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 25977549. S2CID 17412022.

- ^ "Warm Blood Makes Opah an Agile Predator". Southwest Fisheries Science Center. 12 May 2015. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Guimaraes-Cruz, Rodrigo J.; dos Santos, José E.; Santos, Gilmar B. (July–September 2005). "Gonadal structure and gametogenesis of Loricaria lentiginosa Isbrücker (Pisces, Teleostei, Siluriformes)". Rev. Bras. Zool. 22 (3): 556–564. doi:10.1590/S0101-81752005000300005. ISSN 0101-8175.

- ^ Brito, M.F.G.; Bazzoli, N. (2003). "Reproduction of the surubim catfish (Pisces, Pimelodidae) in the São Francisco River, Pirapora Region, Minas Gerais, Brazil". Arquivo Brasileiro de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia. 55 (5): 624–633. doi:10.1590/S0102-09352003000500018. ISSN 0102-0935.

- ^ Peter Scott: Livebearing Fishes, p. 13. Tetra Press 1997. ISBN 1-56465-193-2

- ^ a b Meisner, A & Burns, J: Viviparity in the Halfbeak Genera Dermogenys and Nomorhamphus (Teleostei: Hemiramphidae)" Journal of Morphology 234, pp. 295–317, 1997

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 375.

- ^ Pitcher, Tony J. (1986). "12. Functions of Shoaling Behaviour in Teleosts". The Behaviour of Teleost Fishes. Springer. pp. 294–337. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-8261-4_12. ISBN 978-1-4684-8263-8.

- ^ a b Bertucci, F.; Ruppé, L.; Wassenbergh, S.V.; Compère, P.; Parmentier, E. (29 October 2014). "New Insights into the Role of the Pharyngeal Jaw Apparatus in the Sound-Producing Mechanism of Haemulon Flavolineatum (Haemulidae)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 217 (21): 3862–3869. doi:10.1242/jeb.109025. hdl:10067/1197840151162165141. PMID 25355850.

- ^ Colson, D.J.; Patek, S.N.; Brainerd, E.L.; Lewis, S.M. (February 1998). "Sound production during feeding in Hippocampus seahorses (Syngnathidae)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 51 (2): 221–229. Bibcode:1998EnvBF..51..221C. doi:10.1023/A:1007434714122. S2CID 207648816.

- ^ Oliveira, T.P.R.; Ladich, F.; Abed-Navandi, D.; Souto, A.S.; Rosa, I.L. (26 June 2014). "Sounds produced by the longsnout seahorse: a study of their structure and functions". Journal of Zoology. 294 (2): 114–121. doi:10.1111/jzo.12160.

- ^ a b Fine, L.F.; King, C.B.; Cameron, T.M. (16 October 2009). "Acoustical properties of the swimbladder in the oyster toadfish Opsanus tau". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (21): 3542–3552. doi:10.1242/jeb.033423. PMC 2762879. PMID 19837896.

- ^ Fine, M.L.; Waybright, T.D. (15 October 2015). "Grunt variation in the oyster toadfish Opsanus tau:effect of size and sex". PeerJ. 3 (1330): e1330. doi:10.7717/peerj.1330. PMC 4662586. PMID 26623178.

- ^ a b c Ricci, S.W.; Bohnenstiehl, D. R.; Eggleston, D.B.; Kellogg, M.L.; Lyon, R.P. (8 August 2017). "Oyster toadfish (Opsanus tau) boatwhistle call detection and patterns within a large-scale oyster restoration site". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0182757. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1282757R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182757. PMC 5549733. PMID 28792543.

- ^ Skoglund, C.R. (1 August 1961). "Functional analysis of swimbladder muscles engaged in sound productivity of the toadfish". Journal of Cell Biology. 10 (4): 187–200. doi:10.1083/jcb.10.4.187. PMC 2225107. PMID 19866593.

- ^ Parmentier, E.; Tock, J.; Falguière, J.C.; Beauchaud, M. (22 May 2014). "Sound production in Sciaenops ocellatus: Preliminary study for the development of acoustic cues in aquaculture" (PDF). Aquaculture. 432: 204–211. Bibcode:2014Aquac.432..204P. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2014.05.017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 380.

- ^ Wyman, Richard L.; Ward, Jack A. (1972). "A Cleaning Symbiosis between the Cichlid Fishes Etroplus maculatus and Etroplus suratensis. I. Description and Possible Evolution". Copeia. 1972 (4): 834–838. doi:10.2307/1442742. JSTOR 1442742.

- ^ A.G. Zapata, A. Chiba and A. Vara. Cells and tissues of the immune system of fish. In: The Fish Immune System: Organism, Pathogen and Environment. Fish Immunology Series. (eds. G. Iwama and T.Nakanishi,), New York, Academic Press, 1996, pp. 1–55.

- ^ D.P. Anderson. Fish Immunology. (S.F. Snieszko and H.R. Axelrod, eds), Hong Kong: TFH Publications, Inc. Ltd., 1977.

- ^ Chilmonczyk, S. (1992). "The thymus in fish: development and possible function in the immune response". Annual Review of Fish Diseases. 2: 181–200. doi:10.1016/0959-8030(92)90063-4.

- ^ Hansen, J.D.; Zapata, A.G. (1998). "Lymphocyte development in fish and amphibians". Immunological Reviews. 166: 199–220. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01264.x. PMID 9914914. S2CID 7965762.

- ^ Küchler AM, Gjini E, Peterson-Maduro J, Cancilla B, Wolburg H, Schulte-Merker S (2006). "Development of the Zebrafish Lymphatic System Requires Vegfc Signaling" (PDF). Current Biology. 16 (12): 1244–1248. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.026. PMID 16782017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Flajnik, M. F.; Kasahara, M. (2009). "Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: genetic events and selective pressures". Nature Reviews Genetics. 11 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1038/nrg2703. PMC 3805090. PMID 19997068.

- ^ "Table 1: Numbers of threatened species by major groups of organisms (1996–2004)". iucnredlist.org. Archived from the original on 30 June 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ Sobel, J. (1996). "Gadus morhua". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1996: e.T8784A12931575. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1996.RLTS.T8784A12931575.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ NatureServe (2014). "Cyprinodon diabolis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2014: e.T6149A15362335. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T6149A15362335.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Musick, J.A. (2000). "Latimeria chalumnae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2000: e.T11375A3274618. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T11375A3274618.en. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W.; Liu, K.M.; Lowe, C.G.; Marshall, A.; Pacoureau, N.; Romanov, E.; Sherley, R.B.; Winker, H. (2019). "Carcharodon carcharias". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T3855A2878674. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, pp. 449–450.

- ^ "Call to halt cod 'over-fishing'". BBC News. 5 January 2007. Archived from the original on 17 January 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ "Tuna groups tackle overfishing". BBC News. 26 January 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 462.

- ^ "UK 'must shield fishing industry'". BBC News. 3 November 2006. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ "EU fish quota deal hammered out". BBC News. 21 December 2006. Archived from the original on 26 December 2006. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ "Ocean study predicts the collapse of all seafood fisheries by 2050". phys.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2006.

- ^ "Atlantic bluefin tuna could soon be commercially extinct". Archived from the original on 30 April 2007. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ Helfman, Collette & Facey 1997, p. 463.

- ^ "Threatened and Endangered Species: Pallid Sturgeon Scaphirhynchus Fact Sheet". Archived from the original on 26 November 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Atlas of Exotic Fishes in the Mediterranean Sea. 2nd Edition. 2021. (F. Briand Ed.) CIESM Publishers, Paris, Monaco 366 p.[1] Archived 6 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Briand, Frederic and Galil, Bella 2002. Alien marine organisms introduced by ships – An overview https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240305530

- ^ Spinney, Laura (4 August 2005). "The little fish fight back". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2006.

- ^ "Stop That Fish!". The Washington Post. 3 July 2002. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Spalding, Mark (11 July 2013). "Sustainable Ancient Aquaculture". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ a b Helfman, Gene S. (2007). Fish Conservation: A Guide to Understanding and Restoring Global Aquatic Biodiversity and Fishery Resources. Island Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59726-760-1.

- ^ "World Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture" (PDF). fao.org. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ EDF Seafood Selector: Fish Choices that are Good for You and the Oceans on the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) website. Last access 1/21/2024.

- ^ Beard, T. Douglas, ed. (2011). The Angler in the Environment: Social, Economic, Biological, and Ethical Dimensions. Bethesda, MD: American Fisheries Society. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-934874-24-0.

- ^ Hickley, Phil; Tompkins, Helena, eds. (1998). Recreational Fisheries: Social, Economic and Management Aspects. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-852-38248-6.

- ^ a b c d e Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8. Archived from the original on 20 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d Hyde, Walter Woodburn (2008) [1946]. Paganism to Christianity in the Roman Empire. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-60608-349-9. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ^ Sherwood, Yvonne (2000), A Biblical Text and Its Afterlives: The Survival of Jonah in Western Culture, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–8, ISBN 978-0-521-79561-6, archived from the original on 17 March 2023, retrieved 12 December 2020

- ^ a b Coffman, Elesha (8 August 2008). "What is the origin of the Christian fish symbol?". Christianity Today. Archived from the original on 30 January 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Piscis Austrinus". allthesky.com. The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations. Archived from the original on 25 November 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Zollinger, Sue Anne (3 July 2009). "Piranha – Ferocious Fighter or Scavenging Softie?". A Moment of Science. Indiana Public Media. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

Sources

- Helfman, G.; Collette, B.; Facey, D. (1997). The Diversity of Fishes (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-86542-256-8.

- Nelson, Joseph S. (2006). Fishes of the World (PDF) (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-75644-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

Further reading

- Eschmeyer, William N.; Fong, Jon David (2013). "Catalog of Fishes". California Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- Helfman, G.; Collette, B.; Facey, D.; Bowen, B. (2009). The Diversity of Fishes: Biology, Evolution, and Ecology (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2494-2. Archived from the original on 26 August 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Moyle, Peter B. (1993) Fish: An Enthusiast's Guide Archived 17 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91665-4 – good lay text.

- Moyle, Peter B.; Cech, Joseph J. (2003). Fishes, An Introduction to Ichthyology (5th ed.). Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 978-0-13-100847-2.

- Scales, Helen (2018). Eye of the shoal: A Fishwatcher's Guide to Life, the Ocean and Everything. Bloomsbury Sigma. ISBN 978-1-4729-3684-4.

- Shubin, Neil (2009). Your inner fish: A journey into the 3.5 billion year history of the human body. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-307-27745-9. Archived from the original on 17 March 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2015. UCTV interview Archived 14 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- ANGFA – Illustrated database of freshwater fishes of Australia and New Guinea

- Fischinfos.de – Illustrated database of the freshwater fishes of Germany at the Wayback Machine (archived 30 November 2011) (in German)

- FishBase online – Comprehensive database with information on over 29,000 fish species

- Fisheries and Illinois Aquaculture Center – Data outlet for fisheries and aquaculture research center in the central US at archive.today (archived 15 December 2012)

- Philippines Fishes – Database with thousands of Philippine Fishes photographed in natural habitat

- The Native Fish Conservancy – Conservation and study of North American freshwater fishes at the Wayback Machine (archived 12 March 2008)

- United Nation – Fisheries and Aquaculture Department: Fish and seafood utilization

- University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections – Digital collection of freshwater and marine fish images

- "Fish". Better Health Channel. Retrieved 26 August 2023. – Health tips from the State government of Victoria, Australia