Beauty and the Beast (1991 film)

| Beauty and the Beast | |

|---|---|

| File:Beautybeastposter.jpg Theatrical poster by John Alvin[1] | |

| Directed by | Gary Trousdale Kirk Wise |

| Screenplay by | Linda Woolverton |

| Story by | Roger Allers Brenda Chapman Chris Sanders Burny Mattinson Kevin Harkey Brian Pimental Bruce Woodside Joe Ranft Tom Ellery Kelly Ashbury Robert Lence |

| Produced by | Don Hahn |

| Starring | Paige O'Hara Robby Benson Richard White Jerry Orbach David Ogden Stiers Angela Lansbury Bradley Michael Pierce Rex Everhart Jesse Corti |

| Narrated by | David Ogden Stiers |

| Edited by | John Carnochan |

| Music by | Alan Menken |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Walt Disney Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 84 minutes |

| Country | Template:Film US |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $25 million[2] |

| Box office | $424,967,620[2] |

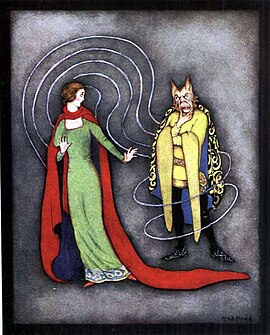

Beauty and the Beast is a 1991 American animated musical fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Feature Animation and distributed by Walt Disney Pictures. The 30th film in the Walt Disney Animated Classics series and the third film of the Disney Renaissance period, the film is based on the fairy tale La Belle et la Bête by Jeanne-Marie Le Prince de Beaumont[3] and uses some ideas from the 1946 film of the same name.[4] The film centers around a prince who is transformed into a Beast and a young woman named Belle whom he imprisons in his castle. To become a prince again, the Beast must love Belle and win her love in return, or he will remain a Beast forever.

The film's animation screenplay was written by Linda Woolverton with story written by Roger Allers, Brenda Chapman, Chris Sanders, Burny Mattinson, Kevin Harkey, Brian Pimental, Bruce Woodside, Joe Ranft, Tom Ellery, Kelly Ashbury, and Robert Lence, directed by Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise, and produced by Don Hahn. The music of the film was composed by Alan Menken and Howard Ashman, both of whom had written the music and songs for Disney's The Little Mermaid. The film was dedicated to Ashman, who died before this film and the next Disney movie Aladdin were finished.

Beauty and the Beast was released on November 13, 1991. The film was a significant commercial and critical success during its initial release, and has now earned over $424 million in box office earnings throughout the world. Beauty and the Beast was also nominated for several awards, and won the Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture - Musical or Comedy, with two other awards for its music. Famously, Beauty and the Beast was the first ever animated film to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture, and was the only animated film to hold this honor until 2009 and 2010, respectively, when Pixar's animated films Up and Toy Story 3 were nominated. Beauty and the Beast received a total of six nominations, including Best Picture, Best Original Score, Best Sound, and three nominations for its song. It ended up winning two, for Best Original Score and Best Original Song for the song "Beauty and the Beast". In 2002, Beauty and the Beast was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."

A direct-to-video midquel called Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas was released in 1997. It was followed in 1998 by another midquel, Belle's Magical World, and later by a stage production of the same name and a television spin-off series, Sing Me a Story with Belle. An IMAX special edition version of the original film was released in 2002, with a new five-minute musical sequence included. After the success of the 3D re-release of The Lion King, the film returned to theaters in 3D on January 13, 2012.[5]

Plot

An enchantress disguised as an old beggar woman offers a young prince a rose in exchange for a night's shelter. When he turns her away, she punishes him by transforming him into an ugly Beast and turning his servants into furniture and other household items. She gives him a magic mirror that will enable him to view faraway events, and she gives him the rose, which will bloom until his twenty-first birthday. He must love and be loved in return before all the rose's petals have fallen off, or he will remain a Beast forever.

Years later, a beautiful young woman named Belle comes along, living in a nearby French village with her father Maurice, an inventor. Belle loves reading and yearns for a life beyond the village. Her beauty attracts attention in the town and she is pursued by many men, but mostly the arrogant local hunter, Gaston, although Belle has no interest in him, despite the fact that he is sought after by all the single females and is considered godlike in perfection by the male population of the town.

As Maurice travels to a fair, he gets lost on the way and is chased by wolves before stumbling upon the Beast's castle, where he meets the transformed servants Lumière (a candelabra), Cogsworth (a clock), Mrs. Potts (a teapot), and her son Chip (a teacup). The Beast imprisons Maurice, but Belle is led back to the castle by Maurice's horse and offers to take her father's place which the Beast agrees to. While Gaston is sulking over his humiliation in the tavern, Maurice tells him and the other villagers what happened but they think he has lost his mind.

At the castle, the Beast orders Belle to dine with him, but she refuses, and Lumiere disobeys his order not to let her eat. After Cogsworth gives her a tour of the castle, she finds the rose in the forbidden West Wing and the Beast angrily chases her away. Frightened, she tries to escape, but she and her horse are attacked by wolves. After the Beast rescues her, she nurses his wounds, and he begins to develop feelings for her. The Beast grants Belle access to the castle library, which impresses Belle and they become friends, growing closer as they spend more time together. Meanwhile, the spurned Gaston pays the warden of the town's insane asylum to have Maurice committed unless Belle agrees to Gaston's marriage proposal.

Back at the castle Belle and the Beast share a romantic evening together. Belle tells the Beast she misses her father, and he lets her use the magic mirror to see him. When Belle sees him dying in the woods in an attempt to rescue her, the Beast allows her to leave to rescue her father, giving her the mirror to remember him by. As he watches her leave, the Beast admits to Cogsworth that he loves Belle.

Belle finds her father and takes him home. Gaston arrives to carry out his plan, but Belle proves Maurice sane by showing them the Beast with the magic mirror. Realizing Belle has feelings for the Beast, Gaston arouses the mob's anger against the Beast, telling them that the Beast is a man-eating monster that must be brought down immediately, and leads them to the castle. Gaston locks Belle and Maurice in the basement, though Chip, who had hidden himself in Belle's baggage, uses one of Maurice's inventions to free them.

While the servants and Gaston's mob fight in the castle, Gaston hunts down the Beast. The Beast is initially too depressed to fight back, but he regains his will when he sees Belle returning to the castle with Maurice. After winning a heated battle, the Beast spares Gaston's life, demanding that he leave the castle and never return. As the Beast is about to reunite with Belle, Gaston, refusing to admit defeat, stabs the Beast from behind, but loses his balance and falls off the balcony to his death.

Just as the Beast succumbs to his wounds, Belle whispers that she loves him, breaking the spell just as the rose's last petal falls. The Beast comes back to life, his human form restored. As he and Belle kiss, the castle and its inhabitants return to their previous states as well. Belle and the prince dance in the ballroom with her father and the humanized servants happily watching.

Cast and crew

Cast and characters

- Paige O'Hara as Belle - (Animation - James Baxter and Mark Henn) - A bookish young woman who falls in love with the Beast. In their effort to enhance the character from the original story, the filmmakers felt that Belle should be "unaware" of her own beauty and made her "a little odd".[6] Wise recalls casting O'Hara because of a "unique tone" she had, "a little bit of Judy Garland", whose appearance she was modeled after.[7]

- Robby Benson as the Beast - (Animation - Glen Keane) - A cold-hearted prince transformed into a beast as punishment for his selfishness. Chris Sanders, one of the film's storyboard artists, drafted the designs for the Beast and came up with designs based on birds, insects and fish before coming up with something close to the final design.[8] Glen Keane, supervising animator for the Beast, refined the design by going to the zoo and studying the animals on which the Beast was based.[8] Benson commented, "There's a rage and torment in this character I've never been asked to use before."[9] The filmmakers commented that "everybody was big fee-fi-fo-fum and gravelly" while Benson's voice had the "big voice and the warm, accessible side" and that "you could hear the prince beneath the fur".[8]

- Richard White as Gaston - (Animation - Andreas Deja) - A highly egotistical hunter who vies for Belle's hand in marriage and is determined not to let anyone else win her heart. He commented that they had "big line-ups of good-looking men with deep voices" during the casting auditions, but that Richard White had a "big voice" that "rattled the room".[8] Gaston's supervising animator, Andreas Deja, was pressed by Jeffrey Katzenberg to make Gaston handsome in contrast to the traditional appearance of a Disney villain, an assignment he found difficult at first.[10]

- Jerry Orbach as Lumiere - (Animation - Nik Raineri) - The kind-hearted but rebellious maître d' of the Beast's castle, he has been transformed into a candelabra. He has a habit of disobeying his master's strict rules, sometimes causing tension between them, but the Beast often turns to him for advice. He is depicted as a bit of a ladies' man, as he is frequently seen with Babette the Featherduster and immediately takes to Belle.

- David Ogden Stiers as Cogsworth - (Animation - Will Finn) - The castle majordomo and Lumiere's best friend, transformed into a clock. While he is as good-natured as Lumiere, he is extremely loyal to the Beast so as to save himself and anyone else any trouble, often leading to friction between himself and Lumiere. Stiers also voices the Narrator.

- Angela Lansbury as Mrs. Potts - (Animation - David Pruiksma) - The head of the castle kitchens, turned into a teapot, who takes a motherly attitude toward Belle. The filmmakers went through several names for Mrs. Potts, such as "Mrs. Chamomile", before Ashman suggested the use of simple and concise names for the household objects.[8]

- Bradley Michael Pierce as Chip - (Animation - David Pruiksma) - A teacup and Mrs. Potts' son. Originally intended to have only one line, the filmmakers were impressed with Pierce's performance and expanded the character's role significantly, eschewing a mute Music Box character.[8]

- Rex Everhart as Maurice - (Animation - Ruben A. Aquino) Belle's inventor father.

- Jesse Corti as Lefou - (Animation - Chris Wahl) - Gaston's bumbling and often mistreated, but loyal and rather clever sidekick.

- Hal Smith as Philippe - (Animation - Russ Edmonds) - Belle's horse.

- Jo Anne Worley as the Wardrobe - (Animation - Tony Anselmo) The castle's authority over fashion, and a former opera singer, turned into a wardrobe. The character of Wardrobe was introduced by visual development person Sue C. Nichols to the then entirely male cast of servants, and was originally a more integral character named "Madame Armoire". Wardrobe is known as "Madame de la Grande Bouche" (Madame Big Mouth) in the stage adaptation of the film.

- Mary Kay Bergman and Kath Soucie as the Bimbettes - A trio of village girls who constantly fawn over Gaston. Known as the "Silly Girls" in the stage adaption.

- Brian Cummings as the Stove - The castle's chef who was transformed into a stove.

- Alvin Epstein as the Bookseller

- Tony Jay as Monsieur D'Arque - The owner of the Maison de Lune. Gaston bribes him to help him in his plan to blackmail Belle.

- Alec Murphy as the Baker

- Kimmy Robertson as the Featherduster - A featherduster and Lumiere's lover. She is named "Babette" in the stage adaptation of the film, and "Fifi" in Belle's Magical World.

- Frank Welker as the Footstool - The castle's pet dog turned into a footstool.

Production

Early versions

Walt Disney sought out other stories to turn into feature films after the success of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and Beauty and the Beast was among the stories he considered.[6][11] Attempts to develop the Beauty and the Beast story into a film were made in the 1930s and 1950s, but were ultimately given up because it "proved to be a challenge" for the story team.[6] Peter M. Nichols states Disney may later have been discouraged by Jean Cocteau having already done his version.[12]

Decades later, after the success of Who Framed Roger Rabbit in 1988, the Disney studio resurrected Beauty and the Beast as a project for the satellite animation studio it had set up in London, England to work on Roger Rabbit.[13] Richard Williams, who had directed the animated portions of Roger Rabbit, was approached to direct, but declined in favor of continuing work on his long-gestating project The Thief and the Cobbler.[13] In his place, Williams recommended his colleague, English animation director Richard Purdum, and work began under producer Don Hahn on a non-musical version of Beauty and the Beast set in Victorian France.[13] At the behest of Disney CEO Michael Eisner, Beauty and the Beast became the first Disney animated film to use a screenwriter. This was an unusual production move for an animated film, which is traditionally developed on storyboards rather than in scripted form.[14] Linda Woolverton wrote the original draft of the story before storyboarding began, and worked with the story team to retool and develop the film.[14]

Script rewrite and musicalization

Upon seeing the initial storyboard reels in 1989, Walt Disney Studios chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg ordered that the film be scrapped and started over from scratch.[13] A few months after starting anew, Purdam resigned as director. The studio had approached Ron Clements and John Musker to direct the film but turned down the offer saying they were "tired" after just having finished directing Disney's recent success The Little Mermaid. Disney then hired first-time feature directors Kirk Wise and Gary Trousdale. Wise and Trousdale had previously directed the animated sections of Cranium Command, a short film for a Disney EPCOT theme park attraction.[13] In addition, Katzenberg asked songwriters Howard Ashman and Alan Menken, who had written the song score for The Little Mermaid to turn Beauty and the Beast into a Broadway-style musical film in the same vein as Mermaid. Ashman, who at the time had learned he was dying of complications from AIDS, had been working with Disney on a pet project of his, Aladdin, and only reluctantly agreed to join the struggling production team.[13]

To accommodate Ashman's failing health, pre-production of Beauty and the Beast was moved from London to the Residence Inn in Fishkill, New York, close to Ashman's New York City home.[13] Here, Ashman and Menken joined Wise, Trousdale, Hahn, and Woolverton in retooling the film's script.[6][14] Since the original story had only two major characters, the filmmakers enhanced them, added new characters in the form of enchanted household items who "add warmth and comedy to a gloomy story" and guide the audience through the film, and added a "real villain" in the form of Gaston.[6] These ideas were somewhat similar to elements of the 1946 French film version of Beauty and the Beast, which introduced the character of Avenant, an oafish suitor somewhat similar to Gaston[15] as well as inanimate objects coming to life in the Beast's castle.[16] The animated objects were, however, given distinct personalities in the Disney version. By early 1990, Katzenberg had approved the revised script, and storyboarding began again.[6][14] The production flew story artists back and forth between California and New York for storyboard approvals from Ashman, though the team was not told the reason why.[6]

Animation

Production of Beauty and the Beast had to be completed on a compressed timeline of two years rather than four because of the loss of production time spent developing the earlier Purdam version of the film.[8] Most of the production was done at the main Feature Animation studio, housed in the Air Way facility in Glendale, California. A smaller team at the Disney-MGM Studios theme park in Lake Buena Vista, Florida assisted the California team on several scenes, particularly the "Be Our Guest" number.[6]

Beauty and the Beast was the second film produced using CAPS (Computer Animation Production System), a digital scanning, ink, paint, and compositing system of software and hardware developed for Disney by Pixar.[6][13] The software allowed for a wider range of colors, as well as soft shading and colored line effects for the characters, techniques lost when the Disney studio abandoned hand inking for xerography in the late 1950s.[8] CAPS also allowed the production crew to simulate multiplane effects: placing characters and/or backgrounds on separate layers and moving them towards/away from the camera on the Z-axis to give the illusion of depth, as well as altering the focus of each layer.

In addition, CAPS allowed easier combination of hand-drawn art with computer-generated imagery, which before had to be plotted to animation cels and painted traditionally.[6][17] This technique was put to significant use during the "Beauty and the Beast" waltz sequence, in which Belle and Beast dance through a computer-generated ballroom as the camera dollies around them in simulated 3D space.[6][8] The filmmakers had originally decided against the use of computers in favor of traditional animation, but later, when the technology had improved, decided it could be used for the one scene in the ballroom.[12] The success of the ballroom sequence helped convince studio executives to further invest in computer animation.[18]

Music

Ashman and Menken wrote the Beauty song score during the pre-production process in Fishkill, the opening operetta-styled "Belle" being their first composition for the film.[6] Other songs included "Be Our Guest", sung to Belle by the objects when she becomes the first visitor to eat at the castle in a decade, "Gaston", a solo for the swaggering villain, "Human Again", a song describing Belle and Beast's growing love from the objects' perspective, the love ballad "Beauty and the Beast", and the climactic "The Mob Song".

As story and song development came to a close, full production began in Burbank while voice and song recording began in New York City.[6] The Beauty songs were mostly recorded live with the orchestra and the voice cast performing simultaneously rather than overdubbed separately, in order to give the songs a cast album-like "energy" the filmmakers and songwriters desired.[8]

During the course of production, many changes were made to the structure of the film, necessitating the replacement and re-purposing of songs. After screening a mostly animated version of the "Be Our Guest" sequence, story artist Bruce Woodside suggested that the objects should be singing the song to Belle rather than her father.[6] Wise and Trousdale agreed, and the sequence and song were retooled to replace Maurice with Belle.[6]

"Human Again" was dropped from the film before animation began, as its lyrics caused story problems about the timeline over which the story takes place.[6] This required Ashman and Menken to write a new song in its place. "Something There", in which Belle and Beast sing (via voiceover) of their growing fondness for each other, was composed late in production and inserted into the script in place of "Human Again".[8] Menken would later revise "Human Again" for inclusion in the 1994 Broadway stage version of Beauty and the Beast, and another revised version of the song was added to the film itself in a new sequence created for the film's Special Edition re-release in 2002.[6][8]

Ashman died of AIDS-related complications on March 14, 1991, eight months prior to the release of the film. He never saw the finished film, and his work on Aladdin was completed by another lyricist, Tim Rice.[13] A tribute to the lyricist was included at the end of the credits crawl: "To our friend, Howard, who gave a mermaid her voice, and a beast his soul. We will be forever grateful. Howard Ashman: 1950–1991".

A pop version of the "Beauty and the Beast" theme, performed by Céline Dion and Peabo Bryson over the end credits, was released as a commercial single from the film's soundtrack, supported with a music video. The Dion/Bryson version of "Beauty and the Beast" became an international pop hit, reaching the Top Ten of the singles charts in the United States and the United Kingdom[19][20] Later home video releases of Beauty and the Beast would include, as bonus features, new music videos featuring covers of the title song by Jump 5 (for the 2002 DVD release) and Jordin Sparks (for the 2010 Blu-Ray/DVD release).

Musical numbers

- "Belle (Bonjour)" - Belle, Gaston, and Townspeople

- "Belle" (Reprise) - Belle

- "Gaston" - Gaston, LeFou, and Townspeople

- "Gaston" (Reprise) - Gaston and LeFou

- "Be Our Guest" - Lumière, Mrs. Potts, and the Enchanted Objects

- "Something There" - Belle, Beast, Lumière, Cogsworth, and Mrs. Potts

- "Human Again" (added in the 2002 special edition) - Lumière, Cogsworth, Mrs. Potts, Wardrobe, Chip, and Enchanted Objects

- "Beauty and The Beast" - Mrs. Potts

- "The Mob Song" - Gaston, LeFou, and Townspeople

- "Transformation (Beauty and the Beast - Reprise)" - Chorus

Release and re-releases

The film was shown at the New York Film Festival in September 1991. Because the animation was only about 70% complete, the film was shown as a "work in progress." Storyboards and pencil tests were used in place of the remaining 30%. In addition, parts of the film that were finished were "stepped back" to previous versions of completion. The "work-in-progress" version of Beauty and the Beast played to a standing ovation from the film festival audience.[13] The completed film would also be screened out of competition at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival.[21] The finished film premiered at the El Capitan Theatre in Hollywood on November 13, 1991, and went into wide release through Walt Disney Pictures on November 22.

Disney initially planned a re-release of the film to be released theatrically in December 1998 in an attempt of counterprogramming against DreamWorks' The Prince of Egypt. The idea to restore the "Human Again" sequence was originally for this re-issue. However, due to impending competition from the aforementioned Prince of Egypt as well as The Rugrats Movie, Babe: Pig in the City and Jack Frost as well as Disney's own holiday release schedule being quite full with Enemy of the State, A Bug's Life and Mighty Joe Young, the re-release was delayed to spring 1999. When Disney decided to bump Doug's 1st Movie from direct-to-video to a theatrical release, that film took the re-release's date, delaying it to the holiday season. Presumably due to competition, like the year before, and Disney's own efforts to promote Toy Story 2, this release date was also canceled.

In 2002, Beauty and the Beast was added to the United States National Film Registry as being deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." The film was restored and remastered for its New Year's Day, 2002 re-release in IMAX theatres in a special edition edit including a new musical sequence. For this version of the film, much of the animation was cleaned up, a new sequence set to the deleted song "Human Again" was inserted into the film's second act, and a new digital master from the original CAPS production files was used to make the high resolution IMAX film negative.

A sing along edition of the film, hosted by Jordin Sparks, was released in select theaters on September 29 and October 2, 2010. Prior to the showing of the film Sparks showed an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the newly restored high definition animated classic and the making of her all-new Beauty and the Beast music video. There was also commentary from producer Don Hahn, interviews with the cast and an inside look at how the animation was created.[22]

A 3D version of the film was originally scheduled to be released in US theatres on February 12, 2010, but the project was postponed.[23] On August 25, 2011, Disney announced that the 3D version of the film would make its cinematic debut in the United States at Hollywood's El Capitan Theatre from September 2–15, 2011.[24] Disney spent less than $10 million on the 3D conversion.[25] After the successful 3D re-release of The Lion King, Disney announced a wide 3D re-release of Beauty and the Beast in North America beginning January 13, 2012.[26]

Home media releases

The film was released to VHS and Laserdisc on October 30, 1992 and in the UK in autumn, 1993 for a limited season as part of the Walt Disney Classics series, and was later put on moratorium. This version contains a minor edit to the film: skulls that appear in Gaston's pupils for two frames during his climatic fall to his death were removed for the original home video release.[8] No such edit was made to later reissues of the film. The "work-in-progress" version screened at the New York Film Festival was also released on VHS and Laserdisc at this time.

Beauty and the Beast: Special Edition, as the enhanced version of the film released in IMAX/large-format is called, was released on 2-Disc "Platinum Edition" DVD and VHS on October 8, 2002. The DVD set features three versions of the film: the extended IMAX Special Edition with the "Human Again" sequence added, the original theatrical version, and the New York Film Festival "work-in-progress" version. This release went to "Disney Vault" moratorium status in January 2003, along with its direct to video follow-ups Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas and Belle's Magical World.

The film was released from the Disney vault on October 5, 2010 as the second of Disney's Diamond Editions, in the form of a 3-disc Blu-ray Disc and DVD combination pack;[27] representing the first release of Beauty and the Beast on home video in high-definition format.[28] This edition consists of four versions of the film: the original theatrical version, an extended version, the New York Film Festival storyboard-only version, and a fourth iteration displaying the storyboards via picture-in-picture alongside the original theatrical version.[29][30] However, one revised shot from the special extended edition appeared in all 4 versions of the film. This was the shot at the very end of the musical number "Something There" where Mrs. Potts said to Chip, "I'll tell you when you're older" and kissed him on the nose. A two-disc DVD edition was released on November 23, 2010.[27] A 5-disc combo pack, featuring Blu-ray 3D, Blu-ray 2D, DVD and Digital copy, was released on October 4, 2011. The 3D combo pack is identical to the original Diamond Edition except for the added 3D disc and digital copy.[31]

Reception

Upon the theatrical release of the finished version, the film was universally praised, with Roger Ebert giving it four stars out of four and saying that "Beauty and the Beast reaches back to an older and healthier Hollywood tradition in which the best writers, musicians and filmmakers are gathered for a project on the assumption that a family audience deserves great entertainment, too." He ranked the film as the third best film of 1991. James Berardinelli gave the film a four out of four stars and says, "As a romance, Beauty and the Beast is a delightful confection, creating a pair of memorable, three-dimensional characters and giving us reason to root for their union." Berardinelli has called the film the greatest animated film of all time and has ranked it #56 in his Top 100 Films, ahead of other famous films like #71 The Wizard of Oz, #80 To Kill a Mockingbird, and #94 Lawrence of Arabia. The film received mostly positive reviews, among them some of the best notices the studio had received since the 1940s.[13] Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator, shows Beauty and the Beast with a 92% approval rating as of February 2012 averaged from 83 reviews of the original theatrical release and later theatrical and home video versions.[32] The use of computer animation, particularly in the "Beauty and the Beast" ballroom sequence, was singled out in several reviews as one of the film's highlights.[8]

Smoodin writes in his book Animating Culture that the studio was trying to make up for earlier gender stereotypes with this film.[33] Smoodin also states that, in the way it has been viewed as bringing together traditional fairy tales and feminism as well as computer and traditional animation, the film’s "greatness could be proved in terms of technology narrative or even politics".[34] Another author writes that Belle "becomes a sort of intellectual less by actually reading books, it seems, than by hanging out with them," but says that the film comes closer than other “Disney-studio” films to "accepting challenges of the kind that the finest Walt Disney features met".[35] David Whitley writes in The Idea of Nature in Disney Animation that Belle is different from earlier Disney heroines in that she is mostly free from the burdens of domestic housework, although her role is somewhat undefined in the same way that "contemporary culture now requires most adolescent girls to contribute little in the way of domestic work before they leave home and have to take on the fraught, multiple responsibilities of the working mother".[36] Whitley also notes other themes and modern influences, such as the film's critical view of Gaston’s chauvinism and attitude towards nature, the cyborg-like servants, and the father’s role as an inventor rather than a merchant.[36]

Betsy Hearne, editor of The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, writes that the film belittles the original story's moral about "inner beauty", as well as the heroine herself, in favor of a more brutish struggle; "In fact," she says, "it is not Beauty's lack of love that almost kills Disney's beast, but a rival's dagger."[37]

Stefan Kanfer writes in his book Serious Business that in this film "the tradition of the musical theater was fully co-opted", such as in the casting of Broadway performers Angela Lansbury and Jerry Orbach.[38]

IGN named Beauty and the Beast as the greatest animated film of all time, directly ahead of WALL-E.[39]

Box-office performance

During its initial release in 1991, the film was a significant success at the box office, with $145,863,363 in revenues in North America alone.[2] It ranked as the third most-successful film of 1991 in North America, surpassed only by the summer blockbusters Terminator 2: Judgment Day and Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.[40] At the time Beauty and the Beast was the most successful animated Disney film release, and the first animated film to reach $100 million in North America.[41][42] In its IMAX re-release, it earned $25,487,190 in North America and $5,546,156 in other territories for a worldwide total of $31,033,346.[43] It has also earned $9,818,365 from its 3D re-release overseas.[2] During the opening weekend of its North American 3D re-release in 2012, Beauty and the Beast grossed $17.8 million, coming in at the #2 spot behind Contraband, and also achieved the highest opening weekend for an animated film in January.[44][45] The film was expected to make $17.5 million over the weekend, however, the results topped its forecast and the expectations of box office analysts.[46][47] This re-release ended its run on May 3, 2012 and earned $47,617,067, which brings the film's total gross in North America to $218,967,620.[48] It has also made an estimated $206,000,000 in other territories for a worldwide total of $424,967,620.[2]

Merchandise and spin-offs

Beauty and the Beast merchandise covered a wide variety of products, among them storybook versions of the film's story, a comic book based on the film published by Disney Comics, toys, children's costumes, and other items. In addition, the character of Belle has been integrated into the "Disney Princess" line of Disney's Consumer Products division, and appears on merchandise related to that franchise.

In 1995, a live-action children's series entitled Sing Me a Story with Belle began running in syndication, remaining on the air through 1999. Two direct-to-video midquels (which take place during the timeline depicted in the original film) were produced by Walt Disney Television Animation: Beauty and the Beast: The Enchanted Christmas in 1997 and Belle's Magical World in 1998.

Stage musical

According to an article in The Houston Chronicle, "The catalyst for Disney's braving the stage was an article by New York Times theater critic Frank Rich that praised Beauty and the Beast as 1991's best musical.... Theatre Under The Stars executive director Frank Young had been trying to get Disney interested in a stage version of Beauty about the same time Eisner and Katzenberg were mulling over Rich's column. But Young couldn't seem to get in touch with the right person in the Disney empire. Nothing happened till the Disney execs started to pursue the project from their end.... When they asked George Ives, the head of Actors Equity on the West Coast, which Los Angeles theater would be the best venue for launching a new musical, Ives said the best theater for that purpose would be TUTS. Not long after that, Disney's Don Frantz and Bettina Buckley contacted Young, and the partnership was under way."[49] A stage condensation of the film, directed by Robert Jess Roth and choreographed by Matt West, both of whom moved on to the Broadway development, had already been presented at Disneyland at what was then called the Videopolis stage.

"Beauty and the Beast" premiered in a joint production of Theatre Under The Stars and Disney Theatricals at the Music Hall, Houston, Texas, from November 28, 1993, through December 26, 1993.[49]

On Monday, April 18, 1994, "Beauty and the Beast", premiered on Broadway at the Palace Theatre in New York City. The show transferred to the Lunt-Fontanne Theatre on November 11, 1999. The commercial (though not critical) success of the show led to productions in the West End, Toronto, and all over the world. The Broadway version, which ran for over a decade, received a Tony Award, and became the first of a whole line of Disney stage productions. The original Broadway cast included Terrence Mann as the Beast, Susan Egan as Belle, Burke Moses as Gaston, Gary Beach as Lumiere, Heath Lamberts as Cogsworth, Tom Bosley as Maurice, Beth Fowler as Mrs. Potts, and Stacey Logan as Babette the feather duster. Many well-known actors and singers also starred in the Broadway production during its thirteen year run including Kerry Butler, Deborah Gibson, Toni Braxton, Andrea McArdle, Jamie-Lynn Sigler, Christy Carlson Romano, Ashley Brown, and Anneliese van der Pol as Belle; Chuck Wagner, James Barbour, and Jeff McCarthy as the Beast; Meshach Taylor, Bryan Batt, Jacob Young, and John Tartaglia as Lumiere; and Marc Kudisch, Christopher Sieber, and Donny Osmond as Gaston. The show ended its Broadway run on July 29, 2007 after 46 previews and 5,461 performances. As of 2012, it is still Broadway's eighth longest-running show in history.

Video games

There are several video games that are loosely based on the film:

- Beauty and the Beast is an action platformer developed and published by Hudson Soft for the NES. It was released in Europe in 1994.[50] Gaston, logically, is the final boss of the game because he wants to kill the Beast, marry Belle and force her to give birth to nothing but baby boys (that look like Gaston).

- Disney's Beauty and the Beast is an action platformer for the SNES. It was developed by Probe Entertainment and published by Hudson Soft in North America and Europe in November 1994 and February 23, 1995, respectively. The game was published by Virgin Interactive in Japan on July 8, 1994.[51] The entire game is played through the perspective of the Beast. As the Beast, the player must get Belle to fall in love so that the curse cast upon him and his castle will be broken, she will marry him and become a princess. The final boss of the game is Gaston, a hunter who will try to steal Belle from the Beast. There is even a snowball fight scene in the middle of the game and cutscenes between stages that tells the story of Beauty and the Beast.

- Beauty & The Beast: Belle's Quest is an action, platformer for the Sega Mega Drive/Genesis. Developed by Software Creations, the game was released in North America in 1993.[52] It is one of two video games based on the film that Sunsoft published for the Genesis,[50] the other being Beauty & The Beast: Roar of the Beast. Characters from the film like Gaston can help the player past tricky situations. As Belle, the player must reach the Beast's castle and break the spell to live happily ever after. To succeed, she must explore the village, forest, castle, and snowy forest to solve puzzles and mini-games while ducking or jumping over enemies. Belle's health is represented by a stack of blue books, which diminishes when she touches bats, rats, and other hazards in the game. Extra lives, keys and other items are hidden throughout the levels. While there is no continue or game saving ability, players can use a code to start the game at any of the seven levels.[53]

- Beauty & The Beast: Roar of the Beast is the title of a side-scrolling video game for the Sega Genesis/Mega Drive. The game was one of two games based on the film released for the Sega Genesis, the other game being Beauty & The Beast: Belle's Quest, both of which were produced by Sunsoft and released in 1993. As the Beast, the player must successfully complete several levels, based on scenes from the film, in order to protect the castle from invading villagers and forest animals and rescue Belle from the evil Gaston.[54] Intermission screenshots between each level help to move the story along, as do mini-games. The Beast can crouch, jump, swing his fists, and use a special roar attack that will freeze the on-screen enemies for a brief period. He can sometimes locate items within a level to restore some of his health, and the game provides unlimited continues. It was often described as having a high difficulty level.[55]

- Disney's Beauty & The Beast: A Boardgame Adventure is a Disney Boardgame adventure for the Game Boy Color.

- Kingdom Hearts is an RPG series crossing over the universes of its original characters, Final Fantasy and various Disney settings. Among the huge cast of characters are several from Beauty and the Beast, with a world based on the movie (Beast's Castle) featuring prominently in Kingdom Hearts II and Kingdom Hearts: 358/2 Days. Featured characters are Belle, Beast, Lumiere, Cogsworth, Mrs. Potts, Chip and Madame la Grande Bouche. Notably, their home world breaks the tradition of each world featuring a boss fight against the film's respective villain, since Gaston does not make single appearance in the series. Instead, the role of that world's villain is taken by one of the game's originally created villains, Xaldin.

Awards and nominations

Academy Awards

Alan Menken and Howard Ashman's song "Beauty and the Beast" won the Academy Award for Best Original Song, while Menken's score won the award for Best Original Score. Two other Menken and Ashman songs from the film, "Belle" and "Be Our Guest", were also nominated for Best Original Song. Beauty and the Beast was the first picture to receive three Academy Award nominations for Best Original Song, a feat that would be repeated by The Lion King (1994), Dreamgirls (2006), and Enchanted (2007). Academy rules have since been changed to limit each film to two nominations in this category.

The film was also nominated for Best Sound and Best Picture. It was the first animated film ever to be nominated for Best Picture, and remained the only animated film nominated until 2010, when the Best Picture field was widened to ten nominees. It lost to the critically acclaimed thriller The Silence of the Lambs.

With six nominations, the film currently shares the record for the most nominations for an animated film with WALL-E (2008), although, with three nominations in the Best Original Song category, Beauty and the Beast's nominations span only four categories, while WALL-E's nominations cover six individual categories.

Golden Globes

Beauty and the Beast was the first animated film to win a Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy. This feat was repeated by The Lion King and Toy Story 2.

| Award | Result |

|---|---|

| Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy | Won |

| Best Original Score | |

| Best Original Song (for "Beauty and the Beast") | |

| Best Original Song (for "Be Our Guest") | Nominated |

Grammy Awards

| Award | Result |

|---|---|

| Best Album for Children | Won |

| Best Pop Performance by a Group or Duo With Vocal (For "Beauty and the Beast") | |

| Song of the Year (For "Beauty and the Beast") | Nominated |

| Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture | Won |

| Best Song Written Specifically for a Motion Picture or for Television (For "Beauty and the Beast") | |

| Record of the Year (For "Beauty and the Beast") | Nominated |

| Best Pop Instrumental Performance (For "Beauty and the Beast") | Won |

| Album of the Year | Nominated |

Other awards

In June 2008, the American Film Institute revealed its "Ten Top Ten" lists of the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres based on polls of over 1,500 people from the creative community. Beauty and the Beast was acknowledged as the 7th best film in the animation genre.[57][58] In previous lists, it ranked #22 on the Institutes's list of best musicals and #34 on its list of the best romantic American films. On the list of the greatest songs from American films, Beauty and the Beast ranked #62.

| Award | Result |

|---|---|

| ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards: Most Performed Songs in a Motion Picture | Won |

| Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films: Best DVD Classic Film Release | |

| Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films: Best Music | |

| Annie Awards: Best Animated Feature | |

| BAFTA Awards: Best Original Film Score | Nominated |

| BAFTA Awards: Best Special Effects | |

| BMI Film and TV Awards: BMI Film Music Award | Won |

| DVD Exclusive Awards: Best Overall New Extra Features, Library Release | |

| DVD Exclusive Awards: Best Menu Design | Nominated |

| Hugo Awards: Best Dramatic Presentation | |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards: Best Animated Feature | Won |

| Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards: Best Animation | |

| Motion Picture Sound Editors: Best Sound Editing, Animated Feature | |

| National Board of Review: Special Award for Animation | |

| Satellite Awards: Best Youth DVD | Nominated |

| Young Artist Awards: Outstanding Family Entertainment of the Year | Won |

American Film Institute recognition:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies - Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions - #34

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes and Villains:

- Belle - Nominated Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Beauty and the Beast" - #62

- "Be Our Guest" - Nominated

- AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals - #22

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) - Nominated

- AFI's 10 Top 10 - #7 Animated film

References

- ^ Stewart, Jocelyn (2008-02-10). "Artist created many famous film posters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2008-02-12. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2010-03-14 suggested (help) - ^ a b c d e Beauty and the Beast @ Box Office Mojo

- ^ LePrince de Beaumont, Jeanne-Marie (1783). "Containing Dialogues between a Governess and Several Young Ladies of Quality Her Scholars". The Young Misses Magazine. 1 (4 ed.). London: 45–67.

- ^ Ginell, Carl (August 2, 2007). "Beauty and the Beast stellar". Toacorn.com. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Smith, Grady (October 4, 2011). "'Beauty and the Beast,' 'The Little Mermaid,' 'Finding Nemo,' 'Monsters, Inc.' get 3-D re-releases". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved October 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Tale as Old as Time: The Making of Beauty and the Beast (VCD). Walt Disney Home Entertainment. 2002.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (1991). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York.: Hyperion. pp. 160–2. ISBN 1-56282-899-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Trousdale, Gary; Wise, Kirk; Hahn, Don; and Menken, Alan (2002). DVD audio commentary for Beauty and the Beast: Special Edition. Walt Disney Home Entertainment

- ^ Cagle, Jess (December 13, 1991). "Oh, You Beast: Robby Benson roars to his roots — The former teen idol is the voice of Beast in Beauty and the Beast". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (1991). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York.: Hyperion. p. 178. ISBN 1-56282-899-1.

- ^ Sito, Tom (2006). Drawing the Line: The Untold Story of the Animation Unions From Bosko to Bart Simpson. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 301. ISBN 0-8131-2407-7.

- ^ a b Nichols, Peter M. (2003). The New York Times Essential Library: Children's Movies. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 27–30. ISBN 0-8050-7198-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Hahn, Don (2009). Waking Sleeping Beauty (Documentary film). Burbank, California: Stone Circle Pictures/Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Bob (1991). Disney's Art of Animation: From Mickey Mouse to Beauty and the Beast. New York: Hyperion. pp. 142–7. ISBN 1-56282-899-1.

- ^ Griswold, Jerome (2004). The Meanings of "Beauty and the Beast": A Handbook. Broadview Press. p. 249. ISBN 1-55111-563-8.

- ^ Humphreville, Kim. "La Belle et la Bete". WCSU. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ (2006) Audio Commentary by John Musker, Ron Clements, and Alan Menken. Bonus material from The Little Mermaid: Platinum Edition [DVD]. Walt Disney Home Entertainment.

- ^ Kanfer (1997), p. 228.

- ^ "Celine Dion And Peabo Bryson - Beauty And The Beast". Chart Stats. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast (From Beauty and the Beast) - Peabo Bryson". Billboard. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ Mueller Neff, Martha (September 27, 2010). "Dress up, sing along to 'Beauty and the Beast' this week". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ Stewart, Andrew (August 5, 2010). "Disney retools animation slate 3D Beauty reboot, Newt yanked from schedule". Variety.com. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Disney's "Beauty and the Beast" To Be Screened in 3D in Hollywood

- ^ Kaufman, Amy (January 12, 2012). "Movie Projector: 'Beauty and the Beast,' 'Contraband' fight for No. 1". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- ^ Disney Re-Releasing Films In 3D: 'Beauty & The Beast,' 'The Little Mermaid,' Others Coming Back

- ^ a b Gustin, Maija (1 October 2010). "Movie Rewind: Beauty and the Beast". The Observer. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Lufkin, Bryan (1 October 2010). "'Beauty And The Beast' Stars: Where Are They Now?". Starpulse. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Lang, George (1 October 2010). "Blu-ray Review: "Beauty and the Beast: Diamond Edition"". The Oklahoman (NewsOK). Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Bryson, Carey (26 September 2010). "Beauty and the Beast Diamond Edition". About.com / Kids' Movies & TV. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast 3D Diamond Edition Blu-ray Detailed". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ "Beauty and the Beast Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Smoodin, Eric (1993). Animating Culture. Rutger’s University Press. p. 189. ISBN 0-8135-1948-9.

- ^ Smoodin (1993), p. 190.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 571. ISBN 0-19-503759-6.

- ^ a b Whitley, David (2008). The idea of Nature in Disney Animation. Ashgate Publishing Limited. pp. 44–57. ISBN 978-0-7546-6085-9.

- ^ Hearne, Betsy (1992). "You did it, little teacup!". The Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books. 45 (6). Chicago, IL: The university of Chicago Graduate Library School; University of Chicago Press: 145–6. ISSN 0008-9036.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kanfer, Stefan (1997). Serious Business: The Art and Commerce of Animation in America from Betty Boop to Toy Story. Scribner. p. 221. ISBN 0-684-80079-9.

- ^ Collura, Scott; Fowler, Matt; Goldman, Eric; Schedeen, Jesse; Pirrello, Phil; White, Cindy (June 24, 2010). "Top 25 Animated Movies of All-Time". IGN. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ "1991 DOMESTIC GROSSES". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ "$100 Million Movies". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Disney's Animated "Beauty and the Beast" Celebrates 10th Anniversary with Worldwide Large Format Debut at Record 100 Theaters on Jan. 1". The Tech Museum. Retrieved May 09, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Beauty and the Beast (IMAX)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ Box office report: 'Contraband' tops 'Beauty and the Beast 3D' with $24.1 mil

- ^ Weekend Report: 'Contraband' Hijacks MLK Weekend

- ^ Clevland, Ethan (16 January 2012). ""Beauty and the Beast" return with $18.5 million". Big Cartoon News. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ 'Beauty and the Beast' gives 3-D another big boost, but is this really about 3-D or is it just about nostalgia?

- ^ Beauty and the Beast (3D) @ Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b

Evans, Everett (1993-11-28). "Disney Debut; First stage musical, Beauty, will test waters in Houston". The Houston Chronicle. p. 8.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) Cite error: The named reference "chronicle" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Release information". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2008-05-02.

- ^ "Release information". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ "Release information". GameFAQs. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- ^ "Disney's Beauty and the Beast: Belle's Quest (1993) screenshots". MobyGames. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ "Disney's Beauty and the Beast: Roar of the Beast for Genesis (1993)". MobyGames. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

- ^ Search:. "Disney's Beauty and the Beast: Roar of the Beast Review for Genesis: I really tried to play this game... I really tried..." GameFAQs. Retrieved August 14, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "The 64th Academy Awards (1992) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-10-22.

- ^ "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2008.

- ^ "Top Ten Animation". American Film Institute. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

External links

- 1991 films

- 1990s romance films

- American animated films

- American children's films

- American children's fantasy films

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Song Academy Award winners

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- Disney animated features canon

- Disney's Beauty and the Beast

- Films set in France

- Films featuring anthropomorphic characters

- Musical fantasy films

- United States National Film Registry films