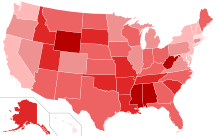

Factions in the Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party in the United States includes several factions, or wings.

During the 19th century, Republican factions included the Half-Breeds, who supported civil service reform; the Radical Republicans, who advocated the abolition of slavery; and the Stalwarts, who supported machine politics. In the 20th century, Republican factions included the Progressive Republicans, the Reagan coalition, and the liberal Rockefeller Republicans. In the 21st century, Republican factions include conservatives (represented in Congress by the Republican Study Committee and the Freedom Caucus), moderates (represented in Congress by the Republican Governance Group), libertarians (represented in Congress by the Republican Liberty Caucus). During and after the presidency of Donald Trump, Trumpist and anti-Trumpist factions arose within the Republican Party.

Modern factions

During the presidency of Barack Obama, the Republican Party experienced internal conflict between its governing class (known as the Republican establishment) and the anti-establishment, small-government Tea Party movement.[1][2][3][4] In 2012, The New York Times identified six wings of the Republican Party: Main Street Voters, Tea Party Voters, Christian Conservatives, Libertarians, The Disaffected, and The Endangered Or Vanished.[5] In 2014, the Pew Research Center split Republican-leaning voters into three groups: Steadfast Conservatives, Business Conservatives, and Young Outsiders.[6] In 2019, during the presidency of Donald Trump, Perry Bacon Jr. of FiveThirtyEight.com asserted that there were five groups of Republicans: Trumpists, Pro-Trumpers, Trump-Skeptical Conservatives, Trump-Skeptical Moderates, and Anti-Trumpers.[7]

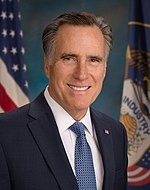

In 2021, following Trump's 2020 loss to Democrat Joe Biden and the 2021 United States Capitol attack, Philip Bump of The Washington Post posited that the Republican Party in the U.S. House of Representatives consisted of three factions: The Trumpists (who voted against the second impeachment of Donald Trump in 2021, voted against stripping Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of her committee assignments, and supported efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election), the accountability caucus (who supported either the Trump impeachment, the effort to discipline Greene, or both), and the pro-democracy Republicans (who opposed the Trump impeachment and the effort to discipline Greene, but also opposed efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election results).[8] Also in 2021, Carl Leubsdorf of the Dallas Morning News asserted that there were three groups of Republicans: Never Trumpers (including Bill Kristol, Sen. Mitt Romney, and Govs. Charlie Baker and Larry Hogan), Sometimes Trumpers (including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell and former U.N. Ambassador Nikki Haley), and Always Trumpers.[9]Pew Research Center identified four Republican-aligned groups of Americans: Faith and Flag Conservatives, Committed Conservatives, the Populist Right, and the Ambivalent Right.[10]

Republican factions in Congress in the 21st century include conservative factions such as the Republican Study Committee[11] and the Freedom Caucus[12] as well as the moderate Republican Governance Group.[13]

Conservatives

The conservative wing grew out of the 1950s and 1960s, with its initial leaders being Senator Robert A. Taft, Russell Kirk, and William F. Buckley Jr. Its central tenets include the promotion of individual liberty and free-market economics and opposition to labor unions, high taxes, and government regulation.[15]

In economic policy, conservatives call for a large reduction in government spending, less regulation of the economy, free trade, and (at least partial) privatization of Social Security. Supporters of supply-side economics predominate, but there are deficit hawks within the faction as well. Before 1930, the Northeastern pro-manufacturing faction of the GOP was strongly committed to high tariffs (a political stance that returned to popularity in many conservative circles starting in the mid-to-late 2010s).[16][17] The conservative wing supports social conservatism (often termed family values) and anti-abortion positions.[18]

Conservatives generally oppose affirmative action, support increased military spending, and are opposed to gun control. On the issue of school vouchers, conservative Republicans split between supporters who believe that "big government education" is a failure and opponents who fear greater government control over private and church schools. Parts of the conservative wing have been criticized for being anti-environmentalist[19][20][21] and promoting climate change denial[22][23][24] in opposition to the general scientific consensus, making them unique even among other worldwide conservative parties.[24]

Social conservatives

|

|

|

The Christian right is a conservative Christian political faction characterized by strong support of socially conservative policies. Christian conservatives principally seek to apply their understanding of the teachings of Christianity to politics and to public policy by proclaiming the value of those teachings or by seeking to use those teachings to influence law and public policy.[25]

In the United States, the Christian right is an informal coalition formed around a core of evangelical Protestants and Roman Catholics, as well as a large number of Latter-day Saints (Mormons).[26][27][28][29] The movement has its roots in American politics going back as far as the 1940s and has been especially influential since the 1970s.[30] In the late 20th century, the Christian right became a notable force in the Republican Party.[31] Republican politicians associated with the Christian right in the 21st century include former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee and former Senator Rick Santorum.[32] Many within the Christian right have also identified as social conservatives, which sociologist Harry F. Dahms has described as Christian doctrinal conservatives (anti-abortion, anti-gay marriage) and gun-use conservatives (pro-NRA) as the two domains of ideology within social conservatism.[33]

Libertarians

|

|

|

Libertarians make up a relatively small faction of the Republican Party.[6][34] In the 1950s and 60s, fusionism—the combination of traditionalist and social conservatism with political and economic right-libertarianism—was essential to the movement's growth.[35] This philosophy is most closely associated with Frank Meyer.[36] Barry Goldwater also had a substantial impact on the conservative-libertarian movement of the 1960s.[37]

Libertarian conservatives in the 21st century favor cutting taxes and regulations, repealing the Affordable Care Act, and protecting gun rights.[5] On social issues, they favor privacy, oppose the USA Patriot Act, and oppose the War on Drugs.[5] On foreign policy, libertarian conservatives favor non-interventionism.[38][39] The Republican Liberty Caucus, which describes itself as "the oldest continuously operating organization in the Liberty Republican movement with state charters nationwide", was founded in 1991.[40] The House Liberty Caucus is a congressional caucus formed by former Representative Justin Amash, a former Republican of Michigan who is now a member of the Libertarian Party.[41] Prominent libertarian conservatives within the Republican Party include New Hampshire Governor Chris Sununu, Senators Mike Lee and Rand Paul, Representative Thomas Massie, and former Representative Ron Paul[42] (who was a Republican prior to 1987, then joined the Libertarian Party from 1987–1996, back to the Republican Party from 1996–2015 and has been a Libertarian since 2015). Ron Paul ran for president once as a Libertarian and twice more recently as a Republican.

The libertarian conservative wing of the party had significant cross-over with the Tea Party movement.[43]

Neoconservatives

|

|

|

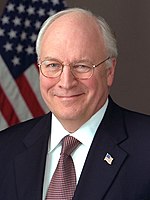

Neoconservatives promote an interventionist foreign policy to promote democracy. Many neoconservatives were in earlier days identified as liberals or were affiliated with the Democrats. Neoconservatives have been credited with importing into the Republican Party a more active international policy. Neoconservatives are amenable to unilateral military action when they believe it serves a morally valid purpose (such as the spread of democracy).[44][45] Many of its adherents became politically famous during the Republican presidential administrations of the late 20th century, and neoconservatism peaked in influence during the administration of George W. Bush, when they played a major role in promoting and planning the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[46] Prominent neoconservatives in the George W. Bush administration included John Bolton, Paul Wolfowitz, Elliott Abrams, Richard Perle, and Paul Bremer. While not identifying as neoconservatives, senior officials Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld listened closely to neoconservative advisers regarding foreign policy, especially the defense of Israel and the promotion of American influence in the Middle East.[citation needed]

Republican members of the 117th Congress with neoconservative stances include Sens. Tom Cotton[47] and Lindsey Graham[48] and Rep. Liz Cheney.[49]

Moderates

|

|

|

A faction that has shrunk since the 1990s, modern Republican moderates are sometimes known as "fiscal conservatives, social liberals".

Moderates tend to be conservative-to-moderate on fiscal issues and moderate-to-liberal on social issues. While they sometimes share the economic views of other Republicans—e.g. balanced budgets, lower taxes, free trade, deregulation, and welfare reform—moderate Republicans differ in that some are for affirmative action,[50] same-sex marriage, gay adoption, legal access to and even funding for abortion, gun control laws, more environmental regulation and anti-climate change measures, fewer restrictions on legal immigration and a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants, and embryonic stem cell research.[51][52] In the 21st century, some former Republican moderates have switched to the Democratic Party.[53][54][55]

Prominent 21st century moderate Republicans include Senators Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine[56][57][58][59] and several governors of northeastern states, such as Charlie Baker of Massachusetts,[60] Larry Hogan of Maryland,[61] Phil Scott of Vermont, and Chris Sununu of New Hampshire.[62] One of the most high-ranking moderate Republicans in recent history was Colin Powell as Secretary of State in the first George W. Bush administration (Powell left the Republican Party in January 2021 following the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol, and had endorsed every Democrat for president in the general election since 2008).[63]

The Republican Governance Group is a caucus of moderate Republicans within the House of Representatives.[13]

Trumpist faction

|

|

|

As of 2021, the dominant faction in the Republican Party[64] consisted of Trumpists, supporters of a movement associated with the political base of Donald Trump.[65] The role of the Tea Party in paving the way for a Trump faction is a subject of debate.[66] When conservative columnist George Will advised voters of all ideologies to vote for Democratic candidates in the Senate and House elections of November 2018,[67] political writer Dan McLaughlin at the National Review responded that doing so would make the Trumpist faction even more powerful within the Republican party.[68] Anticipating Trump's likely defeat in the U.S. presidential election of November 5, 2020, Peter Feaver wrote in Foreign Policy magazine: "With victory having been so close, the Trumpist faction in the party will be empowered and in no mood to compromise or reform."[69] A poll conducted in February 2021 indicated that a plurality of Republicans (46%-27%) would leave the Republican Party to join a new party if Trump chose to create it.[70] Nick Beauchamp, assistant professor of political science at Northeastern University, says he sees the country as divided into four parties, with two factions representing each of the Democratic and Republican parties: "For the GOP, there's the Trump faction—which is the larger group—and the non-Trump faction".[71] Lilliana Mason, associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, states that Donald Trump solidified the trend among Southern white conservative Democrats since the 1960s of leaving the Democratic Party and joining the Republican Party: "Trump basically worked as a lightning rod to finalize that process of creating the Republican Party as a single entity for defending the high status of white, Christian, rural Americans. It's not a huge percentage of Americans that holds these beliefs, and it's not even the entire Republican Party; it's just about half of it. But the party itself is controlled by this intolerant, very strongly pro-Trump faction."[72]

Although the Trump faction of the Republican Party has produced no manifesto,[73] Rachel Kleinfeld, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, describes it as an authoritarian, antidemocratic movement that has successfully weaponized cultural issues, and that cultivates a narrative placing white people, Christians, and men at the top of a status hierarchy as its response to the so-called "Great Replacement" theory, a claim that minorities, immigrants, and women, enabled by Democrats, Jews, and elites, are displacing white people, Christians, and men from their rightful positions in American society.[74]

In a speech he gave on November 2, 2022, at Washington’s Union Station near the U.S. Capitol, President Biden asserted that "the pro-Trump faction" of the Republican Party is trying to undermine the U.S. electoral system and suppress voting rights.[75] Elaine Karmaarck, founding director of the Center for Effective Public Management, writes that although Trump is clearly a major player in the Republican Party, he remains a factional leader, while Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and other contenders are maneuvering to take over the Trump faction.[76]

Anti-Trump

|

|

|

A major divide has formed in the party between those who remain loyal to Donald Trump and those who oppose him.[77] A recent survey concluded that the Republican Party was divided between pro-Trump (the "Trump Boosters," "Die-hard Trumpers," and "Infowars G.O.P." wings) and anti-Trump factions (the "Never Trump" and "Post-Trump G.O.P." wings).[78] Senator John McCain was an early leading critic of Trumpism within the Republican Party, refusing to support the then-Republican presidential nominee in the 2016 presidential election.[79]

Several critics of the Trump faction have faced various forms of retaliation. Cheney was removed from her position as Republican conference chair in the House of Representatives, which was widely perceived as retaliation for her criticism of Trump;[80] in 2022, she was defeated by a pro-Trump primary challenger.[81] Kinzinger decided to retire at the end of his term, while Murkowski faces a pro-Trump primary challenger in 2022 (Kelly Tshibaka).[82][83] A primary challenge to Romney has been suggested[84] by Jason Chaffetz, who has criticized his opponents within the Republican Party as "Trump haters".[85] Representative Anthony Gonzalez, one of 10 House Republicans who voted to impeach Trump over the Capitol riot, called Trump "a cancer" while announcing his retirement.[86]

Political caucuses

| Election year | Republican Study Committee | Republican Governance Group | Freedom Caucus | Problem Solvers Caucus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 157 / 208

|

45 / 208

|

44 / 208

|

29 / 208

|

Historical factions

Half-Breeds

The Half-Breeds were a reformist faction of the 1870s and 1880s. The name, which originated with rivals claiming they were only "half" Republicans, came to encompass a wide array of figures who did not all get along with each other. Generally speaking, politicians labeled Half-Breeds were moderates or progressives who opposed the machine politics of the Stalwarts and advanced civil services reforms.[87]

Progressive Republicans

Historically, the Republican Party included a progressive wing that advocated using government to improve the problems of modern society. Theodore Roosevelt, an early leader of the progressive movement, advanced a "Square Deal" domestic program as president (1901–09) that was built on the goals of controlling corporations, protecting consumers, and conserving natural resources.[88] After splitting with his successor, William Howard Taft, in the aftermath of the Pinchot–Ballinger controversy,[89] Roosevelt sought to block Taft's re-election, first by challenging him for the 1912 Republican presidential nomination, and then when that failed, by entering the 1912 presidential contest as a third party candidate, running on the Progressive ticket. He succeeded in depriving Taft of a second term, but came in second behind Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

After Roosevelt's 1912 defeat, the progressive wing of the party went into decline. Progressive Republicans in the U.S. House of Representatives held a "last stand" protest in December 1923, at the start of the 68th Congress, when they refused to support the Republican Conference nominee for Speaker of the House, Frederick H. Gillett, voting instead for two other candidates. After eight ballots spanning two days, they agreed to support Gillett in exchange for a seat on the House Rules Committee and pledges that subsequent rules changes would be considered. On the ninth ballot, Gillett received 215 votes, a majority of the 414 votes cast, to win the election.[90]

In addition to Theodore Roosevelt, leading early progressive Republicans included Robert M. La Follette, Charles Evans Hughes, Hiram Johnson, William Borah, George W. Norris, William Allen White, Victor Murdock, Clyde M. Reed and Fiorello La Guardia.[91]

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans were a major factor of the party from its inception in 1854 until the end of the Reconstruction Era in 1877. The Radicals strongly opposed slavery, were hard-line abolitionists, and later advocated equal rights for the freedmen and women. They were often at odds with the moderate and conservative factions of the party. During the American Civil War, Radical Republicans pressed for abolition as a major war aim and they opposed the moderate Reconstruction plans of Abraham Lincoln as too lenient on the Confederates. After the war's end and Lincoln's assassination, the Radicals clashed with Andrew Johnson over Reconstruction policy. After winning major victories in the 1866 congressional elections, the Radicals took over Reconstruction, pushing through new legislation protecting the civil rights of African Americans. John C. Frémont of Michigan, the party's first nominee for president in 1856, was a Radical Republican. Upset with Lincoln's politics, the faction split from the Republican to form the short-lived Radical Democracy Party in 1864 and again nominated Frémont for president. They supported Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868 and 1872. As Southern Democrats retook control in the South and enthusiasm for continued Reconstruction declined, their influence within the GOP waned.[92]

Reagan coalition

According to historian George H. Nash, the Reagan coalition in the Republican Party, which centered around Ronald Reagan and his administration throughout all of the 1980s (continuing in the late 1980s with the George H. W. Bush administration), originally consisted of five factions: the libertarians, the traditionalists, the anti-communists, the neoconservatives, and the religious right (which consisted of Protestants, Catholics, and some Jewish Republicans).[15][93]

Rockefeller Republicans

Moderate or liberal Republicans in the 20th century, particularly those from the Northeast and West Coast, were referred to as "The Eastern Establishment" or "Rockefeller Republicans", after Nelson Rockefeller.[94][95][96] Prominent liberal Republicans from the mid-1930s through the 1970s included: Alf Landon, Wendell Willkie, Earl Warren, Thomas Dewey, Prescott Bush, James B. Pearson, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., George W. Romney, Theodore McKeldin, William Scranton, Charles Mathias, Lowell Weicker, Nancy Kassebaum, Jacob Javits, and President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

With their power decreasing in the final decades of the 20th century, many liberal Republicans were replaced by conservative and moderate Democrats, such as those from the Blue Dog or New Democrat coalitions, the latter a faction of Bill Clinton's Third Way movement of the 1990s.[97]

Stalwarts

The Stalwarts were a traditionalist faction that existed from the 1860s through the 1880s. They represented "traditional" Republicans who favored machine politics and opposed the civil service reforms of Rutherford B. Hayes and the more progressive Half-Breeds.[98] They declined following the elections of Hayes and James A. Garfield. After Garfield's assassination by Charles J. Guiteau, his Stalwart Vice President Chester A. Arthur assumed the presidency. However, rather than pursuing Stalwart goals he took up the reformist cause, which curbed the faction's influence.[87]

Tea Party movement

The Tea Party movement was an American fiscally conservative political movement within the Republican Party that began in 2009 following the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States.[99][100] Members of the movement have called for lower taxes, and for a reduction of the national debt of the United States and federal budget deficit through decreased government spending.[101][102] The movement supports small-government principles[103][104] and opposes government-sponsored universal healthcare.[105] It has been described as a popular constitutional movement.[106] On matters of foreign policy, the movement largely supports avoiding being drawn into unnecessary conflicts and opposes "liberal internationalism".[107] Its name refers to the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773, a watershed event in the launch of the American Revolution.[108] By 2016, Politico said that the modern Tea Party movement was "pretty much dead now"; however, the article noted that it seemed to die in part because some of its ideas had been "co-opted" by the mainstream Republican Party.[109]

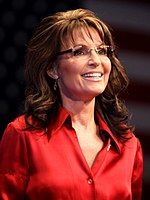

Politicians associated with the Tea Party include former Representatives Ron Paul, Michele Bachmann and Allen West,[110][111] Senators Ted Cruz, Mike Lee and Tim Scott,[112][113][114] former Senator Jim DeMint,[113] former acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney,[115] and 2008 Republican vice presidential nominee and former Alaska Governor Sarah Palin.[111] Although there has never been any one clear founder or leader of the movement, Palin scored highest in a 2010 Washington Post poll asking Tea Party organizers "which national figure best represents your groups?",[116] while Ron Paul was described in a 2011 Atlantic article as its "intellectual godfather".[117] Both Paul and Palin, although ideologically different in many ways, had a major influence on the emergence of the movement due to their separate 2008 presidential primary and vice presidential general election runs respectively.[118][107]

Several political organizations were created in response to the movement's growing popularity in the late 2000s and into the early 2010s, including the Tea Party Patriots, Tea Party Express and Tea Party Caucus.

See also

References

- ^ "Republicans and Tea Party Activists in 'Full Scale Civil War'". ABC News.

- ^ "GOP Establishment Grapples With A Tea Party That Won't Budge". NPR.org. October 2, 2013.

- ^ Abramowitz, Alan. "Not Their Cup of Tea: The Republican Establishment versus the Tea Party". CenterForPolitics.org.

- ^ "Establishment Vs. Tea Party in Primary Showdowns". www.cbsnews.com.

- ^ a b c "A New Guide to the Republican Herd". archive.nytimes.com. August 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Pew Research Center (June 26, 2014). "Beyond Red vs Blue:The Political Typology". Archived from the original on June 29, 2014.

- ^ Bacon, Perry (March 27, 2019). "The Five Wings Of The Republican Party". FiveThirtyEight.com.

- ^ Bump, Philip (February 5, 2021). "The Three Factions of House Republicans". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The GOP is divided into 3 warring factions focused on Trump: Never, Sometimes and Always". Dallas News. February 18, 2021.

- ^ "The Republican Coalition among the U.S. electorate". PewResearch.org. November 9, 2021.

- ^ "How Trump's endorsements are shaping a future GOP Congress". Axios.com. January 5, 2022.

- ^ "House Freedom Caucus: What is it, and who's in it?". PewResearch.org. October 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Cottle, Michelle (May 7, 2021). "Opinion: Liz Cheney Refuses to Lie, So Elise Stefanik Steps Up". The New York Times.

- ^ Jones, Jeffrey (August 2, 2010). "Wyoming, Mississippi, Utah Rank as Most Conservative States". Gallup. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Donald T. Critchlow. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History (2nd ed. 2011).

- ^ Aberbach, Joel D.; Peele, Gillian (2011). Crisis of Conservatism?:The Republican Party, the Conservative Movement, and American Politics After Bush. Oxford University Press. p. 105. ISBN 9780199831364. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018.

- ^ "Trump's 6 populist positions". POLITICO. February 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2020.

- ^ William Martin, With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America (1996).

- ^ Shabecoff, Philip (2000). Earth Rising: American Environmentalism in the 21st Century. Island Press. p. 125. ISBN 9781597263351. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

republican party anti-environmental.

- ^ Hayes, Samuel P. (2000). A History of Environmental Politics Since 1945. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780822972242. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Sellers, Christopher (June 7, 2017). "How Republicans came to embrace anti-environmentalism". Vox. Archived from the original on November 2, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ Dunlap, Riley E.; McCright, Araon M. (August 7, 2010). "A Widening Gap: Republican and Democratic Views on Climate Change". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 50 (5): 26–35. doi:10.3200/ENVT.50.5.26-35. S2CID 154964336.

- ^ Båtstrand, Sondre (2015). "More than Markets: A Comparative Study of Nine Conservative Parties on Climate Change". Politics and Policy. 43 (4): 538–561. doi:10.1111/polp.12122. ISSN 1747-1346.

The U.S. Republican Party is an anomaly in denying anthropogenic climate change.

- ^ a b Chait, Jonathan (September 27, 2015). "Why Are Republicans the Only Climate-Science-Denying Party in the World?". New York. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

Of all the major conservative parties in the democratic world, the Republican Party stands alone in its denial of the legitimacy of climate science. Indeed, the Republican Party stands alone in its conviction that no national or international response to climate change is needed. To the extent that the party is divided on the issue, the gap separates candidates who openly dismiss climate science as a hoax, and those who, shying away from the political risks of blatant ignorance, instead couch their stance in the alleged impossibility of international action.

- ^ Sociology: understanding a diverse society, Margaret L. Andersen, Howard Francis Taylor, Cengage Learning, 2005, ISBN 978-0-534-61716-5, ISBN 978-0-534-61716-5

- ^ Deckman, Melissa Marie (2004). School Board Battles: The Christian Right in Local Politics. Georgetown University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9781589010017. Retrieved April 10, 2014.

More than half of all Christian right candidates attend evangelical Protestant churches, which are more theologically liberal. A relatively large number of Christian Right candidates (24 percent) are Catholics; however, when asked to describe themselves as either "progressive/liberal" or "traditional/conservative" Catholics, 88 percent of these Christian right candidates place themselves in the traditional category.

- ^ Schweber, Howard (February 24, 2012). "The Catholicization of the American Right". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Melissa Marie Deckman (2004). School Board Battles: the Christian right in Local Politics. Georgetown University Press.

- ^ "Five things you should know about Mormon politics". Religion News Service. April 27, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2020.

- ^ "Content Pages of the Encyclopedia of Religion and Social Science". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Haberman, Clyde (October 28, 2018). "Religion and Right-Wing Politics: How Evangelicals Reshaped Elections". Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Cohn, Nate (May 5, 2015). "Mike Huckabee and the Continuing Influence of Evangelicals". Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Smith, Robert B. (2014). Dahms, Harry F. (ed.). Social Conservatism, Distractors, and Authoritarianism: Axiological versus instrumental rationality. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781784412227.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Silver, Nate (April 9, 2015). "There are Few Libertarians But Many Americans Have Libertarian Views". Archived from the original on April 28, 2017.

- ^ Dionne Jr., E.J. (1991). Why Americans Hate Politics. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 161.

- ^ Meyer, Frank (1996). In Defense of Freedom and Other Essays. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

- ^ Poole, Robert (August–September 1998), "In memoriam: Barry Goldwater", Reason (Obituary), archived from the original on June 28, 2009

- ^ Barnett, Randy E. (July 17, 2007). "Libertarians and the War". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ "Toward a Libertarian Foreign Policy". Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ History of the RLC, Republican Liberty Caucus (accessed August 19, 2016).

- ^ Robert Drape, Has the 'Libertarian Moment' Finally Arrived?, New York Times Magazine (August 7, 2016).

- ^ "Libertarians go local". Washington Examiner. August 12, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Ekins, Emily (September 26, 2011). "Is Half the Tea Party Libertarian?". Reason. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

Kirby, David; Ekins, Emily McClintock (August 6, 2012). "Libertarian Roots of the Tea Party". Cato. Archived from the original on December 4, 2018. Retrieved May 3, 2021.{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ John Ehrman. The Rise of Neoconservatism: Intellectual and Foreign Affairs 1945–1994 (2005).

- ^ Justin Vaïsse. Neoconservatism: The Biography of a Movement (2010).

- ^ Record, Jeffery. Wanting War: Why the Bush Administration Invaded Iraq. Potomac Books, Inc. pp. 47–50.

- ^ Beauchamp, Zack (November 5, 2014). "Meet Tom Cotton: Arkansas's next Senator and Rand Paul's worst nightmare". Vox.

- ^ Binelli, Mark (January 6, 2020). "How Lindsey Graham Lost His Way". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "The Larger Lesson of Liz Cheney's Ouster". The New Yorker. May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Losing Its Preference: Affirmative Action Fades as Issue". The Washington Post. 1996. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017.

- ^ Silverleib, Alan. "Analysis: An autopsy of liberal Republicans". cnn.com. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Pear, Robert. "Several G.O.P. Senators Back Money for Stem Cell Research". Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Tatum, Sophie (December 20, 2018). "3 Kansas legislators switch from Republican to Democrat". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel. "Charlie Crist defends party switch". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Hornick, Ed; Walsh, Deidre. "Longtime GOP Sen. Arlen Specter becomes Democrat". CNN. Retrieved January 8, 2021.

- ^ Plott, Elaina (October 6, 2018). "Two Moderate Senators, Two Very Different Paths". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Faludi, Susan (July 5, 2018). "Opinion - Senators Collins and Murkowski, It's Time to Leave the G.O.P." Retrieved February 23, 2019 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Petre, Linda (September 25, 2018). "Kavanaugh's fate rests with Sen. Collins". TheHill. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Connolly, Griffin (October 9, 2018). "Sen. Lisa Murkowski Could Face Reprisal from Alaska GOP". rollcall.com. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Bacon, Perry (March 30, 2018). "How A Massachusetts Republican Became One Of America's Most Popular Politicians". fivethirtyeight.com. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Gov. Larry Hogan positions himself as moderate on the national stage at second inauguration". WUSA. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Richards, Parker (November 3, 2018). "The Last Liberal Republicans Hang On". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Pitofsky, Marina (January 10, 2021). "Colin Powell: 'I can no longer call myself a fellow Republican'". The Hill. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ Aratani, Lauren (February 26, 2021). "Republicans unveil two minimum wage bills in response to Democrats' push". The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 14, 2021. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

In keeping with the party's deep division between its dominant Trumpist faction and its more traditionalist party elites, the twin responses seem aimed at appealing on one hand to its corporate-friendly allies and on the other hand to its populist rightwing base. Both have an anti-immigrant element.

- ^ Katzenstein, Peter J. (March 20, 2019). "Trumpism is US". WZB | Berlin Social Science Center. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- ^ DiSalvo, Daniel (Fall 2022). "Party Factions and American Politics". National Affairs.

- ^ Will, George (June 22, 2018). "Opinion | Vote against the GOP this November". Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ McLaughlin, Dan (June 25, 2018). "Don't Throw the Republicans Out: A Response to George Will". National Review. Archived from the original on June 25, 2018. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Feaver, Peter (November 5, 2020). "What Trump's Near-Victory Means for Republican Foreign Policy". Foreign Policy. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ Elbeshbishi, Susan Page and Sarah. "Exclusive: Defeated and impeached, Trump still commands the loyalty of the GOP's voters". USA TODAY.

- ^ Stening, Tanner (May 26, 2022). "Do political endorsements still matter?". News @ Northeastern. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Homans, Charles (March 17, 2022). "Where Does American Democracy Go From Here?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 17, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Spiegeleire, Stephan De; Skinner, Clarissa; Sweijs, Tim (2017). The Rise of Populist Sovereignism: What It Is, Where It Comes From, and What It Means for International Security and Defense. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. ISBN 978-94-92102-59-1.

- ^ Kleinfeld, Rachel (September 15, 2022). "Five Strategies to Support U.S. Democracy". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022.

- ^ Helderman, Rosalind S.; Abutaleb, Yasmeen (November 2, 2022). "Biden warns GOP could set nation on 'path to chaos' as democratic system faces strain". Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 3, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Kamarck, Elaine (May 19, 2022). "Just how 'Trumpy' is the Republican Party? Lessons from Republican primaries so far". Brookings. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ Lauter, David (February 14, 2021). "Loyalty to Trump remains the fault line for Republicans". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 15, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Haberman, Maggie (March 12, 2021). "A survey of Republicans shows 5 factions have emerged after Trump's presidency". The New York Times.

- ^ Dumcius, Gintautas. "Sen. John McCain backs up Mitt Romney, says Donald Trump's comments 'uninformed and indeed dangerous'", The Republican (March 3, 2016). Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ "Republicans oust Rep. Liz Cheney from leadership over her opposition to Trump and GOP election lies". Business Insider. May 12, 2021.

- ^ Enten, Harry (August 24, 2022). "Analysis: Cheney's loss may be the second worst for a House incumbent in 60 years". CNN. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ "Kinzinger gets pro-Trump primary challenger". The Hill. February 25, 2021.

- ^ "Trump endorses Murkowski primary opponent Kelly Tshibaka". Fox News. June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Jason Chaffetz says he's open to challenging Mitt Romney in Utah Senate primary". Washington Examiner. February 16, 2021.

- ^ "Dear Republican Trump haters – What did you get for your trade?". Washington Times. August 16, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (September 17, 2021). "Ohio House Republican, Calling Trump 'a Cancer,' Bows Out of 2022". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Peskin, Allan (1984–1985). "Who Were the Stalwarts? Who Were Their Rivals? Republican Factions in the Gilded Age". Political Science Quarterly. 99 (4): 703–716. doi:10.2307/2150708. JSTOR 2150708.

- ^ Milkis, Sidney (October 4, 2016). "Theodore Roosevelt: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Peri E. (October 4, 2016). "William Taft: Domestic Affairs". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Wolfensberger, Don (December 12, 2018). "Opening day of new Congress: Not always total joy". The Hill. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- ^ Michael Wolraich. Unreasonable Men: Theodore Roosevelt and the Republican Rebels Who Created Progressive Politics (2014).

- ^ "Radical Republican". Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait. The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America (2004).

- ^ "Analysis: An autopsy of liberal Republicans - CNN.com". cnn.com. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Blue wave that swamped New England endangers Yankee Republicans". The CT Mirror. November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Will Pennsylvania Loss Revive Rockefeller Republicans?". Christian Science Monitor. November 8, 1991. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ Lind, Michael. Up From Conservatives. p. 263.

- ^ "Stalwart". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- ^ Connolly, Katie (September 16, 2010). "What exactly is the Tea Party?". bbc.com. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Heath (February 24, 2017). "Do anti-Trump protests really compare to 2009 Tea Party?". TheHill. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Gallup: Tea Party's top concerns are debt, size of government The Hill, July 5, 2010

- ^ Somashekhar, Sandhya (September 12, 2010). Tea Party DC March: "Tea party activists march on Capitol Hill". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ Good, Chris (October 6, 2010). "On Social Issues, Tea Partiers Are Not Libertarians". The Atlantic. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Jonsson, Patrik (November 15, 2010). "Tea party groups push GOP to quit culture wars, focus on deficit". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- ^ Roy, Avik. April 7, 2012. The Tea Party's Plan for Replacing Obamacare. Forbes. Retrieved: March 6, 2015.

- ^ Somin, Ilya (May 26, 2011). "The Tea Party Movement and Popular Constitutionalism". Rochester, NY. SSRN 1853645.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Mead, Walter Russell (March–April 2011). "The Tea Party and American Foreign Policy: What Populism Means for Globalism". Foreign Affairs. pp. 28–44.

- ^ "Boston Tea Party Is Protest Template". UPI. April 20, 2008.

- ^ Jossey, Paul H. "How We Killed the Tea Party". POLITICO Magazine.

- ^ "Allen West joins congressional Tea Party Caucus". Sun Sentinel. February 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Lieb, David. "Tea party focused on coming GOP Senate primaries". The Tribune-Democrat. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive Tim Scott Interview: No Racism in Tea Party". Blogs.cbn.com. September 21, 2010.

- ^ a b Rudin, Ken (July 30, 2012). "Latest Tea Party Vs. GOP Establishment Battle Comes Tuesday In Texas". NPR.org. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ "Ted Cruz: His tea party background, positions on health care and taxes". mercurynews.com. Associated Press. February 3, 2016. Retrieved February 23, 2019.

- ^ Herb, Jeremy (January 23, 2017). "Trump's tea party budget chief on collision course with GOP hawks". Politico.

- ^ Tea Party canvass results, Category: "What They Believe" A Party Face Washington Post October 24, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Green, Joshua (August 5, 2011). "The Tea Party's Brain". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ Williams, Juan (May 10, 2011). "The Surprising Rise of Rep. Ron Paul". Fox News.

Further reading

- Barone, Michael and Richard E. Cohen. The Almanac of American Politics, 2010 (2009). 1,900 pages of minute, nonpartisan detail on every state and district and member of Congress.

- Baker, Peter, and Susan Glasser. The Divider: Trump in the White House, 2017-2021 (2022) excerpt

- Dyche, John David. Republican Leader: A Political Biography of Senator Mitch McConnell (2009).

- Edsall, Thomas Byrne. Building Red America: The New Conservative Coalition and the Drive For Permanent Power (2006). Sophisticated analysis by liberal.

- Crane, Michael. The Political Junkie Handbook: The Definitive Reference Book on Politics (2004). Nonpartisan.

- Frank, Thomas. What's the Matter with Kansas (2005). Attack by a liberal.

- Frohnen, Bruce, Beer, Jeremy and Nelson, Jeffery O., eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006). 980 pages of articles by 200 conservative scholars.

- Hamburger, Tom and Peter Wallsten. One Party Country: The Republican Plan for Dominance in the 21st Century (2006). Hostile.

- Hemmer, Nicole. Partisans: The Conservative Revolutionaries Who Remade American Politics in the 1990s (2022)

- Hewitt, Hugh. GOP 5.0: Republican Renewal Under President Obama (2009).

- Ross, Brian. "The Republican Un-Civil War – The Neocons and the Tea Party Fight for Control of the GOP" (August 9, 2012). Truth-2-Power.

- Wooldridge, Adrian and John Micklethwait. The Right Nation: Conservative Power in America (2004). Sophisticated nonpartisan analysis.

- "A Guide to the Republican Herd" (October 5, 2006). The New York Times.

- "Belief Spectrum Brings Party Splits" (October 4, 1998). The Washington Post.