Yoshirō Mori

Yoshiro Mori | |

|---|---|

森 喜朗 | |

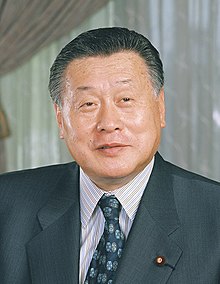

Official portrait, 2000 | |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 5 April 2000 – 26 April 2001 | |

| Monarch | Akihito |

| Preceded by | Keizō Obuchi |

| Succeeded by | Junichiro Koizumi |

| President of the Liberal Democratic Party | |

| In office 5 April 2000 – 24 April 2001 | |

| Secretary-General | |

| Preceded by | Keizō Obuchi |

| Succeeded by | Junichiro Koizumi |

| Minister of Construction | |

| In office 8 August 1995 – 11 January 1996 | |

| Prime Minister | Tomiichi Murayama |

| Preceded by | Koken Nosaka |

| Succeeded by | Eiichi Nakao |

| Minister of International Trade and Industry | |

| In office 12 December 1992 – 20 July 1993 | |

| Prime Minister | Kiichi Miyazawa |

| Preceded by | Kozo Watanabe |

| Succeeded by | Hiroshi Kumagai |

| Minister of Education | |

| In office 27 December 1983 – 1 November 1984 | |

| Prime Minister | Yasuhiro Nakasone |

| Preceded by | Mitsuo Setoyama |

| Succeeded by | Hikaru Matsunaga |

| President of the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games | |

| In office 21 August 2016 – 18 February 2021 | |

| IOC President | Thomas Bach |

| Preceded by | Carlos Arthur Nuzman |

| Succeeded by | Seiko Hashimoto |

| Chair of the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games | |

| In office 24 January 2014 – 18 February 2021 | |

| Preceded by | Committee established |

| Succeeded by | Seiko Hashimoto |

| Member of the House of Representatives from Ishikawa | |

| In office 28 December 1969 – 20 October 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Eiichi Sakata |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Constituency | 1st district (Multi-member) |

| In office 20 October 1996 – 16 November 2012 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Hajime Sasaki |

| Constituency | 2nd district |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 14 July 1937 Nomi, Ishikawa, Empire of Japan |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic (Seiwakai) |

| Spouse | Chieko Maki |

| Children | Yūki Mori Yoko Fujimoto |

| Alma mater | Waseda University (BBA) |

| Website | Yoshiro Mori WebSite |

Yoshirō Mori (森 喜朗, Mori Yoshirō, born 14 July 1937) is a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan and President of the Liberal Democratic Party from 2000 to 2001. He was unpopular in opinion polls during his time in office, and is known for making controversial statements, both during and after his premiership.[a]

Mori was born in present-day Nomi, Ishikawa, Japan, and worked as a journalist before entering politics. In 1969, Mori was elected in the lower house for the Ishikawa 2nd district. He served in government as education minister in 1983 and 1984, international trade and industry minister in 1992 and 1993, and construction minister in 1995 and 1996, and later became secretary general of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). After Keizō Obuchi suffered a stroke and cerebral hemorrhage on 2 April 2000 and was unable to continue in office, Mori became president of the LDP and prime minister days before Obuchi's death.

The media coverage of Mori's term as prime minister was dominated by his gaffes and undiplomatic comments, which led to him becoming unpopular in opinion polls. Members of his cabinet resigned due to fundraising scandals, which also contributed to his unpopularity. In November 2000, with Mori's approval ratings below 30%, opposition politicians attempted to win a vote of no confidence against Mori by soliciting support from rebels within the LDP, although this was quashed after LDP politicians who voted for the measure were threatened with expulsion. Towards the end of Mori's term, his approval rating dropped to single digits. In April 2001, Mori officially announced his intention to resign. Junichiro Koizumi won the subsequent LDP leadership election and became prime minister on 26 April 2001.

After resigning as prime minister, Mori remained a member of the House of Representatives until announcing in July 2012 that he would not stand in the 2012 general election. He remained an important player in Russo-Japanese relations following his resignation as prime minister due to his close personal relationship with Vladimir Putin. Following his premiership, Mori served as the President of the Japan Rugby Football Union as well as the Japan-Korea Parliamentarians' Union. In 2014, he was appointed to head the organizing committee for the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics,[7] but he resigned in 2021 following gaffes made at a committee meeting that were perceived as sexist.[8] In 2003, Mori received the highest distinction of the Scout Association of Japan, the Golden Pheasant Award.

Early life and education

[edit]Yoshiro Mori was born in present-day Nomi, Ishikawa, Japan, as the son of Shigeki and Kaoru Mori, wealthy rice farmers with a history in politics, as both his father and grandfather served as the mayor of Neagari, Ishikawa Prefecture. His mother died when Yoshiro was seven years old. He studied at the Waseda University in Tokyo, joining the rugby union club. He developed a passion for the sport but was never a high-level player; he once compared rugby to his relationship with other parties in the ruling coalition by stating: "In rugby, one person doesn't become a star, one person plays for all, and all play for one."[9]

After university, Mori joined the Sankei Shimbun, a conservative newspaper in Japan.

Political career

[edit]

In 1962, Mori left the newspaper and became secretary of a Diet member, and in the 1969 general election, he was elected in the lower house at age 32. He was reelected 10 consecutive times. In 1980, he was involved in the Recruit scandal about receiving unlisted shares of Recruit (company) before they were publicly traded, and selling them after they were made public for a profit of approximately 1 million dollars.

Mori was education minister in 1983 and 1984, international trade and industry minister in 1992 and 1993, and construction minister in 1995 and 1996.

In 1999, Mori began to assume control of the Mitsuzuka faction (formerly Abe faction) that had been headed by Hiroshi Mitsuzuka in the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).[10]

Prime minister

[edit]In the midst of a battle with Liberal Party leader Ichirō Ozawa, Prime Minister Keizō Obuchi suffered a stroke and cerebral hemorrhage on 2 April 2000 and was unable to continue in office. The Cabinet held an emergency meeting and resigned en masse. Mori, who was the secretary general of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), was unanimously elected president, and became prime minister with the votes of the LDP, New Komeito and New Conservative Party (composed of members who left Ozawa's party on 3 April). Mori announced that he would keep Obuchi's cabinet in place.[11]

Gaffes

[edit]

The media coverage of Mori's term as prime minister was dominated by his gaffes and undiplomatic comments. Even prior to his election as prime minister, he had been described in the Japanese media as having "the heart of a flea and the brain of a shark".[11][12]

- In January 2000, he made a joke about his campaign in the 1969 election: "When I was greeting farmers from my car, they all went into their homes. I felt like I had AIDS."[12]

- In February 2000, when asked about the Year 2000 problem in the United States, Mori quipped that "when there is a blackout, the murderers always come out. It's that type of society."[12]

- At Obuchi's funeral, Mori failed to clap and bow properly before Obuchi's shrine, an important portion of a traditional Japanese funeral rite. The other world leaders present at the funeral, including then U.S. President Bill Clinton, performed the ritual correctly.[3]

- At a meeting of Shinto followers in Tokyo in May 2000, Mori described Japan as "a divine nation (kami no kuni) with the Emperor at its center". This "divine nation statement" stirred controversy in Japan as it invoked the official interpretation of the Emperor as a divine entity during the days of the Empire of Japan.[13] Days after this statement, Mori questioned whether the Japan Communist Party could "ensure Japan's security and defend the kokutai", using a term for Japan's unity with its divine emperor which had not been in common use since World War II.[14]

- During the June 2000 election, when asked about recent newspaper reports that showed that roughly half of the voters still had not decided for whom to vote, he replied that they could "stay in bed for the day".[15]

- In October 2000, during a dialogue with British prime minister Tony Blair, Mori stated that the Japanese government had suggested in 1997 that Japanese nationals believed to be abducted by North Korea be arranged to be "found" elsewhere in order to ensure a smooth normalization of the relation between North Korea and Japan, which upset the foreign ministry and led to calls for Mori's resignation from conservative voices within the LDP.[16]

- In December 2000, pictures appeared in the weekly magazine Shukan Gendai showing him drinking in an Osaka bar with a high-ranking yakuza.[17]

- In February 2001, the US submarine USS Greeneville accidentally hit and sank the Japanese fishing ship Ehime Maru during an emergency surface drill on 9 February 2001, resulting in nine dead students and teachers. Mori continued a round of golf after being told of the incident, for which he was criticized as being politically tone-deaf.[18]

- One unsubstantiated story concerned the 26th G8 summit in 2000, at which upon meeting U.S. President Bill Clinton, Mori was to say "How are you". Instead, he allegedly slipped up and said "Who are you;" Clinton answered "Well, I'm Hillary Clinton's husband", to which Mori replied "Me too". Snopes.com reported that this was obviously a low-quality fabrication/joke and that the same story had been told about Kim Young-sam several months earlier.[19] It was nonetheless reported by some mainstream media outlets such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.[20]

Resignation

[edit]Two senior Mori appointees resigned due to fundraising scandals in August 2000. Mori's disapproval rating neared 60% following these resignations.[21]

In November 2000, with Mori's approval ratings below 30%, opposition politicians attempted to win a vote of no confidence against Mori by soliciting support from rebels within the LDP, guided by Koichi Kato in the so-called "Kato's rebellion".[22] Hiromu Nonaka, the secretary general of the party, quashed the potential revolt by threatening to expel any LDP politicians who voted for the measure.[23] The vote failed 237 to 190.[24] Nonaka resigned days later amid speculation that he would challenge Mori for leadership of the LDP.[25]

Towards the end of Mori's term, his approval rating dropped to single digits.[26] In March 2001, reports surfaced that Mori had told LDP leaders of his plans to resign. Although he denied the reports, they contributed to a massive drop in Japanese stock market prices early that week.[27] On 6 April, he officially announced his intention to resign.[28] Junichiro Koizumi won the subsequent LDP leadership election and became prime minister on 26 April 2001.

Cabinets

[edit]Mori appointed three cabinets. The third cabinet is officially referred to as a continuation of the second cabinet, as the changes came amid a major administrative realignment in January 2001 that eliminated several cabinet positions and renamed several key ministries.

Later years

[edit]After resigning as prime minister, Mori remained a member of the House of Representatives, representing the Ishikawa 2nd district, until announcing in July 2012 that he would not stand in the December 2012 general election.[29]

He was awarded the Padma Bhushan, India's third highest civilian award, in 2004.[30]

Russia diplomacy

[edit]

Mori remained an important player in Russo-Japanese relations following his resignation as prime minister due to his close personal relationship with Vladimir Putin. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda of the Democratic Party of Japan considered tapping Mori in 2012 to resolve the dispute between the two countries over the Kuril Islands, despite the fact that Noda and Mori were from opposing parties in the Diet.[31]

In 2013, Mori met with Putin and Sergey Naryshkin in preparations for a summit between Putin and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe. Mori had at one time suggested that Japan could give Russia three of the four disputed islands in exchange for a peace treaty, which went against the Japanese government's official view that Moscow should acknowledge Japan's ownership of all four.[32]

Mori has a personal connection to Russia, as his father Shigeki Mori developed a relationship with the Siberian town of Shelekhov during his time as mayor of the city of Neagari, and developed a bilateral dialogue to improve the gravesites of Soviet soldiers in Japan and Japanese soldiers in Siberia; he was so close to Russia that Japanese authorities monitored him closely as a potential communist sympathizer. The elder Mori visited Shelekhov more than 15 times during his 35 years in office, and was buried there following his death.[33]

Sports-related advocacy

[edit]Mori became President of the Japan Rugby Football Union in June 2005. It had been hoped his clout would help secure the 2011 Rugby Union World Cup for Japan, but instead the event was awarded to New Zealand in late November 2005.[34] This led Mori to accuse the Commonwealth of Nations countries of "passing the ball around their friends."[35] Mori later assisted in Japan's successful bids for both the 2019 Rugby World Cup and 2020 Summer Olympics.[7]

In 2014, at the age of 76, he was appointed to head the organizing committee for the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. He quipped, "I am destined to live five or six more years if I am lucky. This will be my one last service to the country."[7] However, Mori drew international and domestic criticism for his critical statements about Japan's Olympic figure skaters Mao Asada and Chris Reed and Cathy Reed, who were representing Japan at the 2014 Sochi Olympics.[36]

Another controversy occurred in 2021 when Mori, who at this time was president of the organization responsible for the upcoming Olympic Games, said that women talk too much in meetings.[6] At the organizing committee meeting for the Tokyo Olympics while discussing the objective of aiming for at least 40% of members to be female, he stated that “On boards with a lot of women, the board meetings take so much time. Women have a strong sense of competition. If one person raises their hand, others probably think, I need to say something too. That’s why everyone speaks. [...] You have to regulate speaking time to some extent [...] Or else we’ll never be able to finish”[37] He apologized for his statements and initially stated he would not resign as head of the organizing committee,[38] but on February 11 announced his intention to step down from the post.[39] In his resignation speech the following day, Mori said that he did not intend to demean women, and blamed the media for fueling public anger. He stressed the importance that the Olympics be held in July, adding that the committee's efforts would be wasted if he were to cause trouble by remaining in his post.[8] Seiko Hashimoto, an Olympic bronze medalist in women's speed skating and a seven-time Olympian, was named as Mori's replacement.[40]

LDP funds scandal

[edit]As the former head of the Seiwa Seisaku Kenkyūkai, which was the main faction involved in the 2023–2024 Japanese slush fund scandal, Mori has come into question for his role in the kickback scheme. Incumbent Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has not rejected the idea of forcing him to testify.[41]

Personal life

[edit]Mori is an avid rugby fan as well as an amateur player.[42] He is married to Chieko (born: Chieko Maki), a fellow Waseda University student, and he has a son, Yūki Mori, and a daughter, Yoko Fujimoto.

In 2003, he received the highest distinction of the Scout Association of Japan, the Golden Pheasant Award.[43]

Honours

[edit]- National

- Foreign

Padma Bhushan (2004)

Padma Bhushan (2004)

Order of Brilliant Star with Special Grand Cordon (2006)[44][45]

Order of Brilliant Star with Special Grand Cordon (2006)[44][45]

Medal "In Commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of Saint Petersburg" (2007)

Medal "In Commemoration of the 300th Anniversary of Saint Petersburg" (2007)

Grand Officier, Légion d'honneur (2010)

Grand Officier, Légion d'honneur (2010)

Order of Diplomatic Service Merit Grand Gwanghwa Medal (2010)

Order of Diplomatic Service Merit Grand Gwanghwa Medal (2010)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Profile: Yoshiro Mori BBC News, (2000-11-20, 08:34 GMT

- ^ 噂の眞相特別取材班「『サメの脳ミソ』と『ノミの心臓』を持つ森喜朗 "総理失格" の人間性の証明」(『噂の眞相』2000年6月号、pp.24–31)

- ^ a b Japan's prime minister adds more gaffes at Obuchi funeral Star-Banner

- ^ "Japanese PM sparks holy row". BBC News. 16 May 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Mori's Remarks Again Draw Criticism". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 5 June 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b Rich, Motoko; Hida, Hikari; Inoue, Makiko (3 February 2021). "Tokyo Olympics Chief Apologizes for Remarks Demeaning Women". The New York Times – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ a b c "Mori says he may not live to see 2020 Olympics". AFP. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Tokyo Olympics head quits over sexism row with no successor in sight". Kyodo News. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Famous Ruggers by Wes Clark and others, retrieved 19 August 2009

- ^ Edmund Terence Gómez (2002). Political Business in East Asia. Taylor & Francis Group. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-415-27148-6. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ a b Efron, Sonni (5 April 2000). "A Ruling Party Veteran Becomes Japan's Premier". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ a b c "Profile: Yoshiro Mori". BBC News. 20 November 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Japanese PM sparks holy row". BBC News. 16 May 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Mori's Remarks Again Draw Criticism". Associated Press. 5 June 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Schmetzer, Uli (24 June 2000). "Undecided Voters Are Sleeping Giant of Japan Politics". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Japan: The Mori effect". The Economist. 26 October 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Yakuza Wars". The Asia Pacific Journal. 1 September 2000. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ^ Pellegrini, Frank (15 March 2001). "Yoshiro Mori". TIME. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Who Are You?". Snopes.com. 17 June 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Martin, Peter (19 March 2001). "Farcical US / Japan Summit". ABC AM. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Mori's Woes Grow With Scandals". Los Angeles Times. 3 August 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Rebellion and betrayal in Japanese parliament". the Guardian. 15 November 2000. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "Japan's Ruling Party Moves to Quash Mutiny Over Mori". Associated Press. 20 November 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Efron, Sonni (21 November 2000). "Japanese Premier Survives No-Confidence Vote". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "tions LDP Official Quits; Mori May Be at More Risk". Los Angeles Times. 1 December 2000. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ McCormack, Gavan (24 February 2021). "As Japan Prepares for the Postponed Olympics, a Conservative Old Guard Is Dragging the Country Down". Jacobin. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Pellegrini, Frank (15 March 2001). "Why We Chose Him". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Mori Goes Public With Plan to Quit". Associated Press. 6 April 2001. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ The Daily Yomiuri Ex-PM Mori not to run in next election Retrieved on 24 July 2012

- ^ "Padma Awards" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Westlake, Adam (27 April 2012). "Noda considers asking former PM Mori to help with Russian dispute". Japan Daily Press. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Billones, Cherrie Lou (21 February 2013). "Ex-PM Mori meets with Putin to lay foundation for Abe's visit to Russia". Japan Daily Press. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Reitman, Valerie (28 April 2000). "Personal Element to Japan Premier's Russia Trip". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Richards, p276

- ^ Richards, p277

- ^ "Mori criticizes Asada, draws international fire". The Japan Times. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ^ "Tokyo Olympics Chief Suggests Limits for Women at Meetings". The New York Times. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Treisman, Rachel (4 February 2021). "Facing Backlash For Sexist Remarks, Tokyo Olympics Chief Apologizes But Won't Resign". NPR. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Tokyo Olympics chief Mori to quit over "sexist" remarks". Kyodo News. 11 February 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ "Tokyo 2020: Japan Olympics minister Seiko Hashimoto appointed head of Games". BBC. 18 February 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ "Kishida: LDP to Consider Questioning ex-Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori over Political Funds Scandal". japannews. Jiji Press. 16 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Yoshiro Mori: gaffe-prone Tokyo 2020 chief and former Japan PM". France 24. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ 䝪䞊䜲䝇䜹䜴䝖日本連盟 きじ章受章者 [Recipient of the Golden Pheasant Award of the Scout Association of Japan] (PDF). Reinanzaka Scout Club (in Japanese). 23 May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2020.

- ^ "President Chen Meets with Former Japanese Prime Minister". Office of the President of the Republic of China. 21 November 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

- ^ "President Chen Decorates Former Japanese Prime Minister". Office of the President of the Republic of China. 22 November 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Richards, Huw A Game for Hooligans: The History of Rugby Union (Mainstream Publishing, Edinburgh, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84596-255-5)

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Japanese)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1937 births

- Living people

- People from Nomi, Ishikawa

- Members of the House of Representatives from Ishikawa Prefecture

- Ministers of construction of Japan

- Ministers of economy, trade and industry of Japan

- Education ministers of Japan

- Liberal Democratic Party (Japan) politicians

- Presidents of the Liberal Democratic Party (Japan)

- Liberal Democratic Party prime ministers of Japan

- Presidents of the Organising Committees for the Olympic Games

- Japanese journalists

- Japanese rugby union players

- Russophilia

- Waseda University alumni

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour

- Recipients of the Order of Brilliant Star

- Recipients of the Padma Bhushan in public affairs

- Recipients of the Paralympic Order

- 20th-century prime ministers of Japan

- 21st-century prime ministers of Japan