Raï

| Raï | |

|---|---|

Cover arts of Raï albums of the 1980s | |

| Native name | راي |

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | Early 20th century in the Oranie region, Algeria[2] |

| Fusion genres | |

| Raï'n'B | |

| Local scenes | |

| Other topics | |

| Music of Algeria | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Algeria |

|---|

|

| People |

| Mythology |

| Art |

Raï (/raɪ.i/, /raɪ/; Template:Lang-ar, rāʾy, [raʔi]), sometimes written rai, is a form of Algerian folk music that dates back to the 1920s. Singers of Raï are called cheb (Arabic: شاب) (or shabab, i.e. young) as opposed to sheikh (Arabic: شيخ) (shaykh, i.e. old), the name given to Chaabi singers. The tradition arose in the city of Oran, primarily among the poor. Traditionally sung by men, by the end of the 20th century, female singers had become common. The lyrics of Raï have concerned social issues such as disease and the policing of European colonies that affected native populations.[3]

History

Origins

Raï is a type of Algerian popular music that arose in the 1920s[4][5] in the port city of Oran, and that self-consciously ran counter to accepted artistic and social mores. It appealed to young people who sought to modernize the traditional Islamic values and attitudes. Regional, secular, and religious drum patterns, melodies, and instruments were blended with Western electric instrumentation. Raï emerged as a major world-music genre in the late 1980s.

In the years just following World War I, the Algerian city of Oran—known as "little Paris"—was a melting pot of various cultures, full of nightclubs and cabarets; it was the place to go for a bawdy good time. Out of this milieu arose a group of male and female Muslim singers called chioukhs and cheikhates, who rejected the refined, classical poetry of traditional Algerian music. Instead, to the accompaniment of pottery drums and end-blown flutes, they sang about the adversity of urban life in a raw, gritty, sometimes vulgar, and inevitably controversial language that appealed especially to the socially and economically disadvantaged. The cheikhates further departed from tradition in that they performed not only for women but also and especially for men.

The music performed was called raï. It drew its name from the Algerian Arabic word raï ("opinion" or "advice"), which was typically inserted—and repeated—by singers to fill time as they formulated a new phrase of improvised lyrics. By the early 1940s Cheikha Rimitti el Reliziana had emerged locally as a musical and linguistic luminary in the raï tradition, and she continued to be among the music's most prominent performers into the 21st century.

In the early 20th century, Oran was divided into Jewish, French, Spanish, and Native Algerian quarters. By independence in 1962, the Jewish quarter (known as the Derb), was home to musicians like Reinette L'Oranaise, Saoud l'Oranais and Larbi Bensari. Sidi el Houari was home to Spanish fishermen and many refugees from Spain who arrived after 1939. These two-quarters had active music scenes,[6] and the French inhabitants of the city went to the Jewish and Spanish areas to examine the music. The Arabs of Oran were known for al-andalous, a classical style of music imported from Southern Spain after 1492. Hawzi classical music was popular during this time, and female singers of the genre included Cheikha Tetma, Fadila D'zirya and Myriam Fekkai. Another common musical genre was Bedoui ("Bedouin") (or gharbi ("Western")), which originated from Bedouin chants. Bedoui consisted of Melhun poetry being sung with accompaniment from guellal drums and gaspa Flutes. Bedoui was sung by male singers, known as cheikhs, who were dressed in long, white jellabas and turbans. Lyrics came from the poetry of people such as Mestfa ben Brahim and Zenagui Bouhafs. Performers of bedoui included Cheikh Hamada, Cheikh Mohammed Senoussi, Cheikh Madani, Cheikh Hachemi Bensmir and Cheikh Khaldi. Senoussi was the first to have had recorded the music in 1906.

French colonization of Algeria changed the organization of society, producing a class of poor, uneducated urban men and women. Bedoui singers mostly collaborated with the French colonizers, though one exception from such collaboration was Cheikh Hamada.[7] The problems of survival in a life of poverty were the domain of street musicians who sang bar-songs called zendanis. A common characteristic of these songs included exclamations of the word "raï!" and variations thereof. The word "rai" implies that an opinion is being expressed.

In the 1920s, the women of Oran were held to strict code of conduct. Many of those that failed became social outcasts and singers and dancers. They sang medh songs in praise of the prophet Mohammed and performed for female audiences at ceremonies such as weddings and circumcision feasts. These performers included Les Trois Filles de Baghdad, Soubira bent Menad and Kheira Essebsadija. Another group of female social outcasts were called cheikhas, who were known for their alluring dress, hedonistic lyrics, and their display of a form of music that was influenced from meddhahates and zendani singers. These cheikhas, who sang for both men and women, included people such as Cheikha Remitti el Reliziana, Cheikha Grélo, Cheikha Djenia el Mostganmia, Cheikha Bachitta de Mascara, and Cheikha a; Ouachma el Tmouchentia. The 1930s saw the rise of revolutionary organizations, including organizations motivated by Marxism, which mostly despised these early roots raï singers. At the same time, Arabic classical music was gaining huge popularity across the Maghreb, especially the music of Egypt's Umm Kulthum.

When first developed, raï was a hybrid blend of rural and cabaret musical genres, invented by and targeted toward distillery workers, peasants who had lost their land to European settlers, and other types of lower class citizens. The geographical location of Oran allowed for the spread of many cultural influences, allowing raï musicians to absorb an assortment of musical styles such as flamenco from Spain, gnawa music, and French cabaret, allowing them to combine with the rhythms typical of Arab nomads. In the early 1930s, social issues afflicting the Arab population in the colony, such as the disease of typhus, harassment and imprisonment by the colonial police, and poverty were prominent themes of raï lyrics. However, other main lyrical themes concerned the likes of wine, love, and the meaning and experiences of leading a marginal life. From its origins, women played a significant role in the music and performance of raï. In contrast to other Algerian music, raï incorporated dancing in addition to music, particularly in a mixed-gender environment.[8][9]

In the 1930s, Raï, al-andalousm, and the Egyptian classical style influenced the formation of wahrani, a musical style popularized by Blaoui Houari. Musicians like Mohammed Belarbi and Djelloul Bendaoud added these influences to other Oranian styles, as well as Western piano and accordion, resulting in a style called bedoui citadinisé. Revolt began in the mid-1950s, and musicians which included Houari and Ahmed Saber supported the Front de Libération National. After independence in 1962, however, the government of the Houari Boumédienne regime, along with President Ahmed Ben Bella, did not tolerate criticism from musicians such as Saber, and suppression of Raï and Oranian culture ensued. The number of public performances by female raï singers decreased[clarification needed], which led to men playing an increased role in this genre of music. Meanwhile, traditional raï instruments such as the gasba (reed flute), and the derbouka (North african drums) were replaced with the violin and accordion.[8]

Post-independence

In the 1960s, Bellamou Messaoud and Belkacem Bouteldja began their career, and they changed the raï sound, eventually gaining mainstream acceptance in Algeria by 1964. In the 1970s, recording technology began growing more advanced, and more imported genres had Algerian interest as well, especially Jamaican reggae with performers like Bob Marley. Over the following decades, raï increasingly assimilated the sounds of the diverse musical styles that surfaced in Algeria. During the 1970s, raï artists brought in influences from other countries such as Egypt, Europe, and the Americas. Trumpets, the electric guitar, synthesizers, and drum machines were specific instruments that were put into music. This marked the beginning of pop raï, which was performed by a later generation which adopted the title of Cheb (male) or Chaba (female), meaning "young," to distinguish themselves from the older musicians who continued to perform in the original style.[10] Among the most prominent performers of the new raï were Chaba Fadela, Cheb Hamid,[11] and Cheb Mami.[12] However, by the time the first international raï festival was held in Algeria in 1985, Cheb Khaled had become virtually synonymous with the genre.[13] More festivals followed in Algeria and abroad, and raï became a popular and prominent new genre in the emergent world-music market. International success of the genre had begun as early as 1976 with the rise to prominence of producer Rachid Baba Ahmed.

The added expense of producing LPs as well as the technical aspects imposed on the medium by the music led to the genre being released almost exclusively onto cassette by the early 1980s, with a great deal of music having no LP counterpart at all and a very limited exposure on CD.

While this form of raï increased cassette sales, its association with mixed dancing, an obscene act according to orthodox Islamic views, led to government-backed suppression. However, this suppression was overturned due to raï's growing popularity in France, where it was strongly demanded by the Maghrebi Arab community. This popularity in France was increased as a result of the upsurge of Franco-Arab struggles against racism. This led to a following of a white audience that was sympathetic to the antiracist struggle.[8]

After the election of president Chadli Bendjedid in 1979, Raï music had a chance to rebuild because of his lessened moral and economic restraints. Shortly afterwards, Raï started to form into pop-raï, with the use of instruments such as electrical synthesizers, guitars, and drum machines.[14][15]

In the 1980s, raï began its period of peak popularity. Previously, the Algerian government had opposed raï because of its sexually and culturally risqué topics, such as alcohol and consumerism, two subjects that were taboo to the traditional Islamic culture.

The government eventually attempted to ban raï, banning the importation of blank cassettes and confiscating the passports of raï musicians. This was done to prevent raï from not

only spreading throughout the country, but to prevent it from spreading internationally and from coming in or out of Algeria. Though this limited the professional sales of raï, the music increased in popularity through the illicit sale and exchange of tapes. In 1985, Algerian Colonel Snoussi joined with French minister of culture Jack Lang to convince the Algerian state to accept raï.[16] He succeeded in getting the government to return passports to raï musicians and to allow raï to be recorded and performed in Algeria, with government sponsorship, claiming it as a part of Algerian cultural heritage. This not only allowed the Algerian government to financially gain from producing and releasing raï, but it allowed them to monitor the music and prevent the publication of "unclean" music and dance and still use it to benefit the Algerian State's image in the national world.[17] In 1985, the first state-sanctioned raï festival was held in Algeria, and a festival was also held in january 1986 in with Cheb Khaled, Cheb Saharaoui, Chebba Fadela, Cheb Hamid, Cheb Mami and the group Raï NaraÏ in the theater MC93 of Bobigny, France.

In 1988, Algerian students and youth flooded the streets to protest state-sponsored violence, the high cost of staple foods, and to support the Peoples' Algerian Army.[18] President Chadli Bendjedid, who held power from 1979 to 1992, and his FLN cronies blamed raï for the massive uprising that left 500 civilians dead in October 1988. Most raï singers denied the allegation, including Cheb Sahraoui, who said there was no connection between raï and the October rebellion. Yet raï's reputation as protest music stuck because the demonstrators adopted Khaled's song "El Harba Wayn" ("To Flee, But Where?") to aid their protesting:

Where has youth gone?

Where are the brave ones?

The rich gorge themselves

The poor work themselves to death

The Islamic charlatans show their true face...

You can always cry or complain

Or escape... but where?[19]

In the 1990s, censorship ruled raï musicians. One exiled raï singer, Cheb Hasni, accepted an offer to return to Algeria and perform at a stadium in 1994. Hasni's fame and controversial songs led to him receiving death threats from Islamic fundamentalist extremists. On September 29, 1994, he was the first raï musician to be murdered, outside his parents' home in the Gambetta district of Oran, reportedly because he let girls kiss him on the cheek during a televised concert. His death came amid other violent actions against North African performers. A few days before his death, the Kabyle singer Lounès Matoub was abducted by the GIA. The following year, on February 15, 1995, Raï producer Rachid Baba-Ahmed was assassinated in Oran.

The escalating tension of the Islamist anti-raï campaign caused raï musicians such as Chab Mami and Chaba Fadela to relocate from Algeria to France. Moving to France was a way to sustain the music's existence.[20] France was where Algerians had moved during the post-colonial era to find work, and where musicians had a greater opportunity to oppose the government without censorship.[21]

Though raï found mainstream acceptance in Algeria, Islamic fundamentalists still protested the genre, saying that it was still too liberal and too contrasting to traditional Islamic values. The fundamentalists claimed that the musical genre still promoted sexuality, alcohol and Western consumer culture, but critics of the fundamentalist viewpoint stated that fundamentalists and raï musicians were ultimately seeking converts from the same population, the youth, who often had to choose where they belonged between the two cultures. Despite the governmental support, a split remained between those citizens belonging to strict Islam and those patronizing the raï scene.[22]

International success

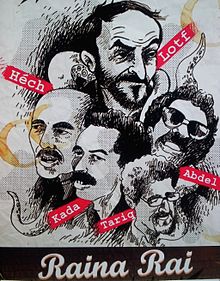

Cheb Khaled was the first musician with international success, including his 1988 duet album with jazz musician Safy Boutella album Kutché, though his popularity did not extend to places such as the United States and Latin America. Other prominent performers of the 1980s included Houari Benchenet, Raïna Raï, Mohamed Sahraoui, Cheb Mami, Cheba Zohra and Cheb Hamid.

International success grew in the 1990s, with Cheb Khaled's 1992 album Khaled. With Khaled no longer in Algeria, musicians such as Cheb Tahar, Cheb Nasro, and Cheb Hasni began singing lover's raï, a sentimental, pop-ballad form of raï music. Later in the decade, funk, hip hop, and other influences were added to raï, especially by performers like Faudel and Rachid Taha, the latter of whom took raï music and fused it with rock. Taha did not call his creation raï music, but rather described it as a combination of folk raï and punk.[23][24][25] Another mix of cultures in Arabic music of the late 1990s came through Franco-Arabic music released by musicians such as Aldo.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw a rise in female raï performers. According to authors Gross, McMurray, and Swedenburg in their article "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identity," raï musician Chaba Zahouania was forbidden by her family to perform or even appear in public. According to Gross et al., the raï record companies have pushed female artists to become more noticed.[26]

In 2000, raï music had international success thanks to Sting's duet with raï singer Cheb Mami on the song "Desert Rose", released January 17, 2000.[27] Sting was widely credited for introducing raï music to Western music audiences, and as such, the song was a success on many charts, reaching No. 2 in Canada, No. 3 in Switzerland, No. 4 in Italy, No. 15 in the UK, and No. 17 in the US.[28] It also reached number 1 on Billboard’s Adult Alternative and Hot Dance Single Sales charts respectively.[29][30]

Censorship

Throughout the course of raï music's development and commercialization in Algeria, there have been many attempts to stifle the genre. From lyrical content to the album cover images, raï has been a controversial music. Religious identity and transnationalism function to define the complexities of Maghrebi identity. This complex identity is expressed through raï music and is often contested and censored in many cultural contexts.

In 1962, as Algeria claimed its national independence, expression of popular culture was stifled by the conservative nature of the people. During this time of drastic restriction of female expression, many men started to become raï singers. By 1979, when president Chadli Bendjedid endorsed more liberal moral and economic standards, raï music became further associated with Algerian youth. The music remained stigmatized amongst the Salafi Islamists and the Algerian government. Termed the "raï generation", the youth found raï as a way to express sexual and cultural freedoms.[31] An example of this free expression is through the lyrics of Cheb Hasni in his song "El Berraka". Hasni sang: "I had her ... because when you're drunk that's the sort of idea that runs through your head!"[32] Hasni challenged the fundamentalists of the country and the condemnation of non-religious art forms.

Raï started to circulate on a larger scale, via tape sales, TV exposure, and radio play. However, the government attempted to "clean up" raï to adhere to conservative values.[31] Audio engineers manipulated the recordings of raï artists to submit to such standards. This tactic allowed for the economy to profit from the music by gaining conservative audiences. The conservativeness not only affected the way listeners received raï music, but also the way the artists, especially female artists, presented their own music. For instance, female raï artists usually do not appear on their album covers. Such patriarchal standards pressure women to societal privacy.[31]

See also

References

- ^ "Introduction to Rai Music". ThoughtCo. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- ^ Auzias, Dominique; Labourdette, Jean-Paul (October 27, 2010). Algérie (in French). Petit Futé. p. 119. ISBN 9782746925755.

- ^ Gross, Joan, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg. "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities." Diaspora 3:1 (1994): 3- 39. Reprinted in The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, ed. by Jonathan Xavier and Renato Rosaldo,

- ^ "Raï". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. October 26, 2009. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ "An Introduction to Rai Music". ThoughtCo. ThoughtCo. May 2, 2017. Retrieved December 30, 2017.

- ^ Morgan, pp 413–424

- ^ "World Music, The Rough Guide" (Document). London: The Rough Guides. 1994. p. 126.

- ^ a b c Joan, Gross (2002). Jonathan Xavier and Renato Rosaldo (ed.). "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap and Franco-Maghrebi Identities" The Anthology of Globalization: A Reader. Oxford: Blackwell.

- ^ Gross, Joan, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg. "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities." Diaspora 3:1 (1994): 3- 39. [Reprinted in The Anthropology of Globalization: A Reader, ed. by Jonathan Xavier and Renato Rosaldo, 1

- ^ Joan, Gross p. 7

- ^ Cheb Hamid All music Retrieved January 20, 2021

- ^ "Cheb Mami sentenced to five years in forced abortion case". Telegraph.co.uk. July 3, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ "Cheb Khaled for Citizens of the World Equus World". www.equus-world.com. Retrieved January 11, 2021.

- ^ https://moodle.brandeis.edu/file.php/3404/pdfs/gross_etal-arab_noise.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Raï – Rebel Music from Algeria

- ^ McMurray, David; Swedenberg, Ted (1992). ""Raï Tide Rising" Middle East Report". Middle East Report (169). 39–42: 39–42. JSTOR 3012952.

- ^ Rod Skilbeck. "Mixing Pop and Politics: The Role of Raï in Algerian Political Discourse". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Meghelli, Samir. "Interview with Youcef (Intik)." In Tha Global Cipha: Hip Hop Culture and Consciousness, ed. by James G. Spady, H. Samy Alim, and Samir Meghelli. 656-67. Philadelphia: Black History Museum Publishers, 2006.

- ^ Lawrence, Bill (February 27, 2002). "Straight Outto Algiers". Norient. Retrieved November 30, 2008.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (February 6, 2002). "Arabic-Speaking Pop Stars Spread the Joy". The New York Times. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ Rod Skilbeck. "Mizing Pop and Politics: The Role of Raï in Algerian Political Discourse". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ Angelica Maria DeAngelis. "Rai, Islam and Masculinity in Maghrebi Transnational Identity". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- ^ JODY ROSEN (March 13, 2005). "MUSIC; Shock the Casbah, Rock the French (And Vice Versa)". The New York Times. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- ^ Curiel, Jonathan. "Arab rocker Rachid Taha's music fueled by politics, punk attitude and – what else? – romance". San Francisco Chronicle. June 27, 2005. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ "Punk on Raï". rockpaperscissors. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ^ Gross, Joan, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg. "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities." Diaspora 3:1 (1994)

- ^ "Archived copy". sting.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Sting". Billboard.

- ^ "Sting". Billboard.

- ^ "Sting". Billboard.

- ^ a b c Gross, Joan, David McMurray, and Ted Swedenburg. "Arab Noise and Ramadan Nights: Raï, Rap, and Franco-Maghrebi Identities." Diaspora 3:1 (1994)

- ^ Freemuse: Algeria: Cheb Hasni—popular rai hero assassinated

Further reading

- Al Taee, Nasser. "Running with the Rebels: Politics, Identity & Sexual Narrative in Algerian Raï". Retrieved on November 22, 2006.

- Schade-Poulsen, Marc. "The Social Significance of Raï: Men and Popular Music in Algeria". copyright 1999 University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77740-8

- Mazouzi, Bezza. La musique algérienne et la question raï, Richard-Masse, Paris, 1990.

- Morgan, Andy. "Music Under Fire". 2000. In Broughton, Simon and Ellingham, Mark with McConnachie, James and Duane, Orla (Ed.), World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East, pp 413–424. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0