Tea

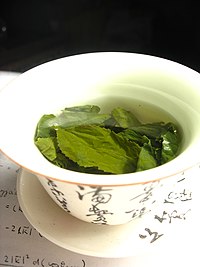

Oolong tea being infused in a gaiwan | |

| Type | Hot or cold beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | China[1] |

| Introduced | Approx. 10th century BC (earliest written records)[2] |

Tea is an aromatic beverage commonly prepared by pouring hot or boiling water over cured leaves of the tea plant, Camellia sinensis.[3] After water, tea is the most widely consumed beverage in the world.[4] It has a cooling, slightly bitter, and astringent flavour that many people enjoy.[5]

Tea originated in China as a medicinal drink.[6] It was first introduced to Portuguese priests and merchants in China during the 16th century.[7] Drinking tea became popular in Britain during the 17th century. The British introduced it to India, in order to compete with the Chinese monopoly on the product.[8]

Tea has long been promoted for having a variety of positive health benefits. Recent studies suggest that green tea may help reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and some forms of cancer, promote oral health, reduce blood pressure, help with weight control, improve antibacterial and antivirasic activity, provide protection from solar ultraviolet light,[9] and increase bone mineral density. Green tea is also said to have "anti-fibrotic properties, and neuroprotective power."[10] Additional research is needed to "fully understand its contributions to human health, and advise its regular consumption in Western diets."[10]

Tea catechins have known anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective properties, help regulate food intake, and have an affinity for cannabinoid receptors, which may suppress pain and nausea and provide calming effects.[11]

Consumption of green tea is associated with a lower risk of diseases that cause functional disability, such as “stroke, cognitive impairment, and osteoporosis” in the elderly.[12][13]

Tea contains L-theanine, an amino acid whose consumption is mildly associated with a calm but alert and focused, relatively productive (alpha wave-dominant) mental state in humans. This mental state is also common to meditative practice.[14]

The phrase herbal tea usually refers to infusions of fruit or herbs made without the tea plant, such as rosehip tea, chamomile tea, or rooibos tea. Alternative phrases for this are tisane or herbal infusion, both bearing an implied contrast with "tea" as it is construed here.

Cultivation and harvesting

Camellia sinensis is an evergreen plant that grows mainly in tropical and subtropical climates.[15] Some varieties can also tolerate marine climates and are cultivated as far north as Cornwall in England,[16] Washington State in the United States,[17] and experimentally in Pembrokeshire, Wales.[18]

Tea plants are propagated from seed and cutting; it takes about 4 to 12 years for a tea plant to bear seed and about three years before a new plant is ready for harvesting.[15] In addition to a zone 8 climate or warmer, tea plants require at least 127 cm (50 inches) of rainfall a year and prefer acidic soils.[19] Many high-quality tea plants are cultivated at elevations of up to 1,500 m (4,900 ft) above sea level. While at these heights the plants grow more slowly, they acquire a better flavour.[20]

Two principal varieties are used: Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, which is used for most Chinese, Formosan and Japanese teas, and Camellia sinensis var. assamica, used in Pu-erh and most Indian teas (but not Darjeeling). Within these botanical varieties, there are many strains and modern clonal varieties. Leaf size is the chief criterion for the classification of tea plants, with three primary classifications being,[21] Assam type, characterised by the largest leaves; China type, characterised by the smallest leaves; Cambodian type, characterised by leaves of intermediate size.

A tea plant will grow into a tree of up to 16 m (52 ft) if left undisturbed,[15] but cultivated plants are generally pruned to waist height for ease of plucking. Also, the short plants bear more new shoots which provide new and tender leaves and increase the quality of the tea.[22]

Only the top 1–2 inches of the mature plant are picked. These buds and leaves are called flushes.[23] A plant will grow a new flush every seven to fifteen days during the growing season. Leaves that are slow in development tend to produce better-flavoured teas.[15] Pests of tea include mosquito bugs that can tatter leaves, so they may be sprayed with insecticides.

Processing and classification

Teas can generally be divided into categories based on how they are processed. There are at least six different types of tea: white, yellow, green, oolong (or wulong), black (called red tea in China), and post-fermented tea (or black tea for the Chinese)[24] of which the most commonly found on the market are white, green, oolong, and black. Some varieties, such as traditional oolong tea[25] and Pu-erh tea, a post-fermented tea, can be used medicinally.[26]

After picking, the leaves of C. sinensis soon begin to wilt and oxidize, unless they are immediately dried. The leaves turn progressively darker as their chlorophyll breaks down and tannins are released. This enzymatic oxidation process is caused by the plant's intracellular enzymes and causes the tea to darken. In tea processing, the darkening is stopped at a predetermined stage by heating, which deactivates the enzymes responsible. In the production of black teas, the halting of oxidation by heating is carried out simultaneously with drying.

Without careful moisture and temperature control during manufacture and packaging, the tea may become unfit for consumption, due to the growth of undesired molds and bacteria.

Blending and additives

Although single-estate teas are available, almost all teas in bags and most other teas sold in the West are now blends. Tea may be blended with other teas from the same area of cultivation or with teas from several different areas. The aim of blending is to obtain a better taste, a higher price, or both, as a more expensive, better-tasting tea is sometimes used to cover the inferior taste of less expensive varieties.

Some commercial teas have been enhanced through additives or special processing. Tea easily retains odors, which can cause problems in processing, transportation, and storage but also allows for the design of an almost endless range of scented and flavoured variants, such as bergamot (Earl Grey), vanilla, and caramel.

Content

Tea contains catechins, a type of antioxidant. In a freshly picked tea leaf, catechins can comprise up to 30% of the dry weight.[citation needed] Catechins are highest in concentration in white and green teas, while black tea has substantially fewer due to its oxidative preparation.[27][28] Research by the U.S. Department of Agriculture has suggested that the levels of antioxidants in green and black teas do not differ greatly, as green tea has an oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) of 1253 and black tea an ORAC of 1128 (measured in μmol TE/100 g).[29] Antioxidant content, measured by the lag time for oxidation of cholesterol, is improved by cold-water steeping of varieties of tea.[11]

Tea also contains the amino acid L-theanine which modulates caffeine's psychoactive effect and contributes to tea's umami taste. Caffeine constitutes about 3% of tea's dry weight, translating to between 30 mg and 90 mg per 8-oz (250-ml) cup depending on type, brand,[30] and brewing method.[31]

Tea also contains small amounts of theobromine and theophylline, which are stimulants and xanthines similar to caffeine.[32]

Because of modern environmental pollution, fluoride and aluminium also sometimes occur in tea. Certain types of brick tea made from old leaves and stems have the highest levels.[33][34]

Although tea contains various polyphenols and tannins, it does not contain tannic acid.[35]

Origin and history

Tea plants are native to East and South Asia, and probably originated around the meeting points of the lands of north Burma and southwest China. Statistical cluster analysis, chromosome number, easy hybridization, and various types of intermediate hybrids and spontaneous polyploids indicate that there is likely a single place of origin for Camellia sinensis, an area including the northern part of Burma, and Yunnan and Sichuan provinces of China.[37] Tea drinking likely began during the Shang Dynasty in China, when it was used for medicinal purposes.[6] It is believed that, soon after, "for the first time, people began to boil tea leaves for consumption into a concentrated liquid without the addition of other leaves or herbs, thereby using tea as a bitter yet stimulating drink, rather than as a medicinal concoction."[6]

No-one is sure of the exact inventor of tea, but Chinese legends attribute the invention of tea to Shennong in 2737 BC.[36] A Chinese inventor was the first person to invent a tea shredder.[38] The first recorded drinking of tea is in China, with the earliest records of tea consumption dating to the 10th century BC.[2][39] Another early credible record of tea drinking dates to the 3rd century AD, in a medical text by Hua Tuo, who stated that "to drink bitter t'u constantly makes one think better." Another early reference to tea is found in a letter written by the Qin Dynasty general Liu Kun.[40] It was already a common drink during the Qin Dynasty (third century BC) and became widely popular during the Tang Dynasty, when it was spread to Korea, Japan and Vietnam. In India it has been drunk for medicinal purposes for a long but uncertain period, but apart from the Himalayan region seems not to have been used as a beverage until the British introduced Chinese tea there.

Tea was first introduced to Portuguese priests and merchants in China during the 16th century, at which time it was termed chá.[7] In 1750, tea experts travelled from China to the Azores, and planted tea, along with jasmine and mallow, to give it aroma and distinction. Both green and black tea continue to grow on the islands, which are the main suppliers to continental Portugal. Catherine of Braganza, wife of King Charles II of England, took the tea habit to Great Britain around 1660, but tea was not widely consumed in Britain until the 18th century, and remained expensive until the latter part of that period. Tea smuggling during the 18th century led to Britain’s masses being able to afford and consume tea, and its importance eventually influenced the Boston Tea Party. The British government eventually eradicated the tax on tea, thereby eliminating the smuggling trade by 1785.[41] In Britain and Ireland, tea had become an everyday beverage for all levels of society by the late 19th century, but at first it was consumed as a luxury item on special occasions, such as religious festivals, wakes, and domestic work gatherings such as quiltings.[42] The price in Europe fell steadily during the 19th century, especially after Indian tea began to arrive in large quantities.

The first European to successfully transplant tea to the Himalayas, Robert Fortune, was sent by the East India Company on a mission to China in 1848 to bring the tea plant back to Great Britain. He began his journey in high secrecy as his mission occurred in the lull between the Anglo-Chinese First Opium War (1839–1842) and Second Opium War (1856–1860), at a time when westerners were not held in high regard.[43]

Tea was first introduced into India by the British, in an attempt to break the Chinese monopoly on tea. The British brought Chinese seeds into Northeast India but the plants failed; they later discovered that a different variety of tea was endemic to Assam and the Northeast region of India and that it was used by local tribes. Using the Chinese planting and cultivation techniques, the British launched a tea industry by offering land in Assam to any European who agreed to cultivate tea for export.[8] Tea was originally consumed only by anglicized Indians; it was not until the 1950s that tea grew widely popular in India through a successful advertising campaign by the India Tea Board.[8]

Health effects

Tea contains a large number of possibly bioactive chemicals, including flavonoids, amino acids, vitamins, caffeine and several polysaccharides, and a variety of health effects have been proposed and investigated.[21] It has been suggested that green and black tea may protect against cancer,[44] though the catechins found in green tea are thought to be more effective in preventing certain obesity-related cancers such as liver and colorectal cancer,[45] while both green and black teas may protect against cardiovascular disease.[44]

Negative effects of tea drinking are centered around the consumption of sugar used to sweeten the tea. Those who consume very large quantities of brick tea may experience fluorosis.[46]

Numerous recent epidemiological studies have been conducted to investigate the effects of green tea consumption on the incidence of human cancers. These studies suggest significant protective effects of green tea against oral, pharyngeal, oesophageal, prostate, digestive, urinary tract, pancreatic, bladder, skin, lung, colon, breast, and liver cancers, and lower risk for cancer metastasis and recurrence.[44] A study led by Dr Kashif Shafique of Glasgow University found a 50% greater risk of prostate cancer amongst men who drank more than seven cups of tea per day, compared to those with moderate or lower tea intake.[47]

Preliminary lab studies show that "a wide variety of commercial teas appear to either deactivate or kill viruses," reports Reuters Health Information. Several types of green and black teas, regular and iced, were tested on animal tissues infected with such viruses as herpes simplex 1 and 2 and the T1 (bacterial) virus. According to researcher Dr. Milton Schiffenbauer of Pace University in New York, "iced tea or regular tea does destroy or inactivate the [herpes] virus within a few minutes." Similar results were obtained with the T1 virus.[48]

Many researchers have been recently taking an interest in the possibility of tea having a notable effect on cardiovascular disease. A large scale study was done in Japan in regards to the effects of consuming large amounts of green tea (more than 6 cups a day) and its relation to heart disease. The experiment showed that individuals who consume between 5 and 10 cups of tea per day have a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.[49]

The word "tea"

The Chinese character for tea is 茶, originally written as 荼 (pronounced tu, used as a word for a bitter herb), and acquired its current form during the Tang Dynasty as used in the eighth-century treatise on tea The Classic of Tea.[50][51][52] The word is pronounced differently in the various Chinese languages, such as chá in Mandarin, zo and dzo in Wu Chinese, and ta and te in Min Chinese.[53][54] One suggestion is that the different pronunciations may have arisen from the different words for tea in ancient China, for example tu (荼) may have given rise to tê.[55] Other words for tea included jia (檟, defined as "bitter tu" during the Han Dynasty), she (蔎), ming (茗) and chuan (荈).[54][56] Most, such as Mandarin and Cantonese, pronounce it along the lines of cha, but Hokkien varieties along the Southern coast of China and in Southeast Asia pronounce it like teh. These two pronunciations have made their separate ways into other languages around the world:[57]

- Te is from the Amoy tê of southern Fujian province. It reached the West from the port of Xiamen (Amoy), once a major point of contact with Western European traders such as the Dutch, who spread it to Western Europe.

- Cha is from the Cantonese chàh of Guangzhou (Canton) and the ports of Hong Kong and Macau, also major points of contact, especially with the Portuguese, who spread it to India in the 16th century. The Korean and Japanese pronunciations of cha however came not from Cantonese, rather they were borrowed into Korean and Japanese during earlier periods of Chinese history.

The widespread form chai comes from Persian چای chay. This derives from Mandarin chá,[58] which passed overland to Central Asia and Persia, where it picked up the Persian grammatical suffix -yi before passing on to Russian, Arabic, Urdu, Turkish, etc.[59]

English has all three forms: cha or char (both pronounced /ˈtʃɑː/), attested from the 16th century; tea, from the 17th; and chai, from the 20th.

Languages in more intense contact with Chinese, Sinospheric languages like Vietnamese, Zhuang, Tibetan, Korean, and Japanese, may have borrowed their words for tea at an earlier time and from a different variety of Chinese, so-called Sino-Xenic pronunciations. Although normally pronounced as cha, Korean and Japanese also retain early pronunciations of ta and da. Japanese has different pronunciations for the word tea depending on when the pronunciations was first borrowed into the language: Ta comes from the Tang Dynasty court at Chang'an: that is, from Middle Chinese; da however comes from the earlier Southern Dynasties court at Nanjing, a place where the consonant was still voiced, as it is today in neighbouring Shanghainese zo.[citation needed] Vietnamese and Zhuang have southern cha-type pronunciations.

Derivatives of te

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrikaans | tee | Armenian | թեյ tey | Basque | tea | Catalan | te | ||

| Czech | té or thé (1) | Danish | te | Dutch | thee | English | tea | Esperanto | teo |

| Estonian | tee | Faroese | te | Finnish | tee | French | thé | West Frisian | tee |

| Galician | té | German | Tee | Greek | τέϊον téïon | Hebrew | תה, te | Hungarian | tea |

| Icelandic | te | Indonesian | teh | Irish | tae | Italian | tè, thè or the | Javanese | tèh |

| Kannada | ಟೀಸೊಪ್ಪು Tee-soppu | Khmer | តែ tae | scientific Latin | thea | Latvian | tēja | Leonese | té |

| Limburgish | tiè | Lithuanian | arbata(2) | Low Saxon | Tee [tʰɛˑɪ] or Tei [tʰaˑɪ] | Malay | teh | Malayalam | തേയില Thēyila |

| Maltese | tè | Norwegian | te | Occitan | tè | Polish | herbata(2) | Scots | tea [tiː] ~ [teː] |

| Scottish Gaelic | tì, teatha | Sinhalese | té තේ | Spanish | té | Sundanese | entèh | Swedish | te |

| Tamil | தேநீர் theneer (3) | Telugu | తేనీరు theneeru (4) | Welsh | te |

Notes:

- (1) té or thé, but this term is considered archaic and is a literary expression; since roughly the beginning of the 20th century, čaj is used for "tea" in Czech language, see the following table

- (2) from Latin herba thea

- (3) neer means water; theyilai means "tea leaf" (ilai = leaf)

- (4) neeru means water; theyaaku means "tea leaf" (aaku = leaf in Telugu)

Derivatives of ta

| Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japanese | だ da, た ta (1) | Korean | 다 da [ta] (1) |

- (1) cha is an alternative pronunciation of "tea" in Japanese and Korean; see below

Derivatives of cha

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 茶 Chá | Assamese | চাহ sah | Bengali | চা cha | Kapampangan | cha | Cebuano | tsa |

| English | cha or char | Gujarati | ચા chā | Japanese | 茶, ちゃ Cha, (1) | Kannada | ಚಹಾ chahā | Khasi | sha |

| Konkani | च्या chyā | Korean | 차 cha (1) | Kurdish | ça | Lao | ຊາ saa | Marathi | चहा chahā |

| Oriya | ଚା cha | Persian | چای chā | Punjabi | چا ਚਾਹ chāh | Portuguese | chá | Sindhi | chahen چانهه |

| Somali | shaah | Sylheti | sa | Tagalog | tsaá | Thai | ชา cha | Tibetan | ཇ་ ja |

| Vietnamese | trà and chè (2) |

Notes:

- (1) The main pronunciations of 茶 in Korea and Japan are 차 cha and ちゃ cha, respectively. (Japanese ocha (おちゃ) is honorific.) These are connected with the pronunciations at the capitals of the Song and Ming dynasties.

- (2) Trà and chè are variant pronunciations of 茶; the latter is used mainly in northern Vietnam and describes a tea made with freshly picked leaves.

Derivatives of chay

| Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name | Language | Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albanian (Tosk) | çaj | Amharic | ሻይ shai | Arabic | شاي shāy | Aramaic | ܟ݈ܐܝ chai | Armenian (Eastern) | թեյ tey |

| Azerbaijani | çay | Bosnian | čaj | Bulgarian | чай chai | Chechen | чай chay | Croatian | čaj |

| Czech | čaj (2) | English | chai | Finnish dialectal | tsai, tsaiju, saiju or saikka | Georgian | ჩაი chai | Greek | τσάι tsái |

| Hindi | चाय chāy | Kazakh | шай shai | Kyrgyz | чай chai | Kinyarwanda | icyayi | Ladino | צ'יי chai |

| Macedonian | чај čaj | Malayalam | ചായ chaaya | Mongolian | цай tsai | Nepali | chiyā चिया | Pashto | چای chay |

| Persian | چای chāī (1) | Romanian | ceai | Russian | чай chay | Serbian | чај čaj | Slovak | čaj |

| Slovene | čaj | Swahili | chai | Tajik | чой choy | Tatar | çäy | Tlingit | cháayu |

| Turkish | çay | Turkmen | çaý | Ukrainian | чай chai | Urdu | چائے chai | Uzbek | choy |

Notes:

- (1) Derived from the earlier pronunciation چا cha.

Etymological observations

The different words for tea fall into two main groups: "te-derived" (Min) and "cha-derived" (Cantonese and Mandarin).[59] The words that various languages use for "tea" reveal where those nations first acquired their tea and tea culture.

- Portuguese traders were the first Europeans to import the herb in large amounts. The Portuguese borrowed their word for tea (chá) from Cantonese in the 1550s via their trading posts in the south of China, especially Macau.[60]

- In Central Asia, Mandarin cha developed into Persian chay, and this form spread with Persian trade and cultural influence.

- Russia (chai) encountered tea in Central Asia.

- The Burmese word for "tea", lahpet (MLCTS: lak hpak, pronounced: [ləpʰɛʔ]) does not fall into either of the two main groups and may have originated independently.

- The Dutch word for "tea" (thee) comes from the Min dialect. The Dutch may have borrowed their word for tea through trade directly from Fujian, or from Fujianese or Malay traders in Java. From 1610 on, the Dutch played a dominant role in the early European tea trade, via the Dutch East India Company, influencing other languages to use the Dutch word for tea. Other European languages whose words for tea derive from the Min dialect (via Dutch) include English, French (thé), Spanish (té), and German (Tee).[60]

- The Dutch first introduced tea to England in 1644.[60] By the 19th century, most British tea was purchased directly from merchants in Canton, whose population uses cha, though English never replaced its Dutch-derived Min word for tea.

At times, a te form will follow a cha form, or vice versa, giving rise to both in one language, at times one an imported variant of the other.

- In North America, the word chai is used to refer almost exclusively to the Indian masala chai (spiced tea) beverage, in contrast to tea itself.

- The inverse pattern is seen in Moroccan colloquial Arabic (Darija), shay means "generic, or black Middle Eastern tea" whereas tay refers particularly to Zhejiang or Fujian green tea with fresh mint leaves. The Moroccans are said to have acquired this taste for green tea—unique in the Arab world—after the ruler Mulay Hassan exchanged some European hostages captured by the Barbary pirates for a whole ship of Chinese tea. See Moroccan tea culture.

- The colloquial Greek word for tea is tsáï, from Slavic chai. Its formal equivalent, used in earlier centuries, is téïon, from tê.

- The Polish word for a tea-kettle is czajnik, which could be derived directly from chai or from the cognate Russian word. However, tea in Polish is herbata, which, as well as Lithuanian arbata, was derived from the Latin herba thea, meaning "tea herb."

- The normal word for tea in Finnish is tee, which is a Swedish loan. However, it is often colloquially referred to, especially in Eastern Finland and in Helsinki, as tsai, tsaiju, saiju or saikka, which is cognate to the Russian word chai. The latter word refers always to black tea, while green tea is always tee.

- In Ireland, or at least in Dublin, the term cha is sometimes used for "tea," as is pre-vowel-shift pronunciation "tay" (from which the Irish Gaelic word tae is derived[citation needed]). Char was a common slang term for tea throughout British Empire and Commonwealth military forces in the 19th and 20th centuries, crossing over into civilian usage.

- The British slang word "char" for "tea" arose from its Cantonese Chinese pronunciation "cha" with its spelling affected by the fact that ar is a more common way of representing the phoneme /ɑː/ in British English.

Tea culture

Tea may be consumed early in the day to heighten calm alertness; it contains L-theanine,[14] theophylline, and bound caffeine[5] (sometimes called theine). Decaffeinated brands are also sold. While herbal teas are also referred to as tea, most of them do not contain leaves from the tea plant.

In different cultures, tea has become a popular way of dieting. It has been credited with helping to boost metabolism and aid people in losing weight. For example, Feiyan tea, a Chinese herbal tea that includes green tea, lotus leaves, cansia seeds, and vegetable sponge is believed to promote weight loss by improving metabolism, reducing blood fat and cholesterol, reducing bloatedness, detoxing the body, and suppressing the appetite. Other examples include herbal teas that contain dandelion or nettle, two herbs that have diuretic properties and are believed to eliminate excess water, hence reducing weight.[61]

While tea is the second most consumed beverage on Earth after water, in many cultures it is also consumed at elevated social events, such as afternoon tea and the tea party. Tea ceremonies have arisen in different cultures, such as the Chinese and Japanese tea ceremonies, each of which employs traditional techniques and ritualised protocol of brewing and serving tea for enjoyment in a refined setting. One form of Chinese tea ceremony is the Gongfu tea ceremony, which typically uses small Yixing clay teapots and oolong tea.

Ireland has, for a long time, been one of the biggest per-capita consumers of tea in the world. The national average is four cups per person per day, with many people drinking six cups or more. Tea in Ireland is usually taken with milk and/or sugar and is slightly spicier and stronger than the traditional English blend. The two main brands of tea sold in Ireland are Lyons and Barry's. The Irish love of tea is perhaps best illustrated by the stereotypical housekeeper, Mrs. Doyle in the popular sitcom Father Ted.

Tea is prevalent in most cultures in the Middle East. In Arab culture, tea is a focal point for social gatherings.

In Pakistan, tea is called chai (written as چائے). Both black and green teas are popular and are known locally as sabz chai and kahwah, respectively. The popular green tea called kahwah is often served after every meal in the Pashtun belt of Balochistan and in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which is where the Khyber Pass of the Silk Road is found.

In the transnational Kashmir region, which straddles the border between India and Pakistan, Kashmiri chai or noon chai, a pink, creamy tea with pistachios, almonds, cardamom, and sometimes cinnamon, is consumed primarily at special occasions, weddings, and during the winter months when it is sold in many kiosks.

In central and southern Punjab and the metropolitan Sindh region of Pakistan, tea with milk and sugar (sometimes with pistachios, cardamom, etc.), commonly referred to as chai, is widely consumed. It is the most common beverage of households in the region. In the northern Pakistani regions of Chitral and Gilgit-Baltistan, a salty, buttered Tibetan-style tea is consumed. In Iranian culture, tea is so widely consumed, it is generally the first thing offered to a household guest.[62]

In the United States and Canada, 80% of tea is consumed cold, as iced tea.[63] Sweet tea is a cultural symbol of the southeastern US, and is common in that portion of the country.

Switzerland has its own unique blend of iced tea, made with the basic ingredients like black tea, sugar, lemon juice and mint, but a variety of Alp herbs are also added to the concoction. Apart from classic flavours like lemon and peach, exotic flavours like jasmine and lemongrass are also very popular.

In India, tea is one of the most popular hot beverages. It is consumed daily in almost all homes, offered to guests, consumed in high amounts in domestic and official surroundings, and is made with the addition of milk with or without spices. It is also served with biscuits dipped in the tea and eaten before consuming the tea. More often than not, it is drunk in "doses" of small cups (referred to as "Cutting" chai if sold at street tea vendors) rather than one large cup. On 21 April 2012, the Deputy Chairman of Planning Commission (India), Montek Singh Ahluwalia, said tea would be declared as national drink by April 2013.[64][65] The move is expected to boost the tea industry in the country. Speaking on the occasion, Assam Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi said a special package for the tea industry would be announced in the future to ensure its development.[66]

In the United Kingdom, it is consumed daily and often by a majority of people across the country, and indeed is perceived as one of Britain's cultural beverages. In British homes, it is customary good manners for a host to offer tea to guests soon after their arrival. Tea is generally consumed at home; outside the home in cafés. Afternoon tea with cakes on fine porcelain is a cultural stereotype, sometimes available in quaint tea-houses. In southwest England, many cafes serve a 'cream tea', consisting of scones, clotted cream, and jam alongside a pot of tea. Throughout the UK, 'tea' may also refer to the evening meal.

In Burma (Myanmar), tea is consumed not only as hot drinks, but also as sweet tea and green tea known locally as laphet-yay and laphet-yay-gyan, respectively. Pickled tea leaves, known locally as laphet, are also a national delicacy. Pickled tea is usually eaten with roasted sesame seeds, crispy fried beans, roasted peanuts and fried garlic chips.

Preparation

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) |

The traditional method of making or brewing a cup of tea is to place loose tea leaves, either directly or in a tea infuser, into a tea pot or teacup and pour freshly boiled water over the leaves. After a few minutes, the leaves are usually removed, either by removing the infuser or by straining the tea while serving.

Most green teas should be allowed to steep for about two or three minutes, although some types of tea require as much as ten minutes, and others as little as 30 seconds. The strength of the tea should be varied by changing the amount of tea leaves used, not by changing the steeping time. The amount of tea to be used per amount of water differs from tea to tea, but one basic recipe may be one slightly heaped teaspoon of tea (about 5 ml) for each teacup of water (200–240 ml) (7–8 oz) prepared as above. Stronger teas, such as Assam, to be drunk with milk, are often prepared with more leaves, and more delicate high-grown teas such as a Darjeeling are prepared with somewhat fewer (as the stronger mid-flavours can overwhelm the champagne notes).

The best temperature for brewing tea depends on its type. Teas that have little or no oxidation period, such as a green or white tea, are best brewed at lower temperatures, between 65 and 85 °C (149 and 185 °F), while teas with longer oxidation periods should be brewed at higher temperatures around 100 °C (212 °F). The higher temperatures are required to extract the large, complex, flavourful phenolic molecules found in fermented tea. In addition, boiling reduces the dissolved oxygen content of water. Dissolved oxygen would otherwise react with phenolic molecules to turn them brown and reduce their potency as antioxidants. To preserve the antioxidant potency, especially for green and white teas brewed at a lower temperature, water should be boiled vigorously to boil off any dissolved oxygen and then allowed to cool to the appropriate temperature before adding to the tea. An additional health benefit of boiling water before brewing tea is the sterilisation of the water and reduction of any dissolved VOCs, chemicals which are often harmful.[67][68]

As well as changing the potency of the antioxidants, the steep`s temperature and time greatly effects the taste, especially with white and green teas. Camellia sinensis naturally contains tannins, which are brought out in higher quantities with the tea's exposure to hot water for longer periods. In black teas, the tannins are part of the natural flavour, as they tend to be rich and bolder. However in white and green teas, which tend to be more delicate, the tannins frequently give the tea a bitter taste which is commonly thought of as unpleasant.

| Type | Water temp. | Steep time | Infusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| White tea | 65 to 70 °C (149 to 158 °F) | 1–2 minutes | 3 |

| Yellow tea | 70 to 75 °C (158 to 167 °F) | 1–2 minutes | 3 |

| Green tea | 75 to 80 °C (167 to 176 °F) | 1–2 minutes | 4–6 |

| Oolong tea | 80 to 85 °C (176 to 185 °F) | 2–3 minutes | 4–6 |

| Black tea | 99 °C (210 °F) | 2–3 minutes | 2–3 |

| Pu'er tea | 95 to 100 °C (203 to 212 °F) | Limitless | Several |

| Tisanes | 99 °C (210 °F) | 3–6 minutes | Varied |

Some tea sorts are often brewed several times using the same leaves. Historically in China, tea is divided into a number of infusions. The first infusion is immediately poured out to wash the tea, and then the second and further infusions are drunk. The third through fifth are nearly always considered the best infusions of tea, although different teas open up differently and may require more infusions of hot water to produce the best flavour.[69]

A tea cosy is often used to keep the temperature of the tea in a teapot constant.

One way to taste a tea, throughout its entire process, is to add hot water to a cup containing the leaves and after about 30 seconds to taste it. As the tea leaves unfold (known as "The Agony of the Leaves"), they expose various parts of themselves to the water and thus the taste evolves. Continuing this from the very first flavours to the time beyond which the tea is quite stewed will allow an appreciation of the tea throughout its entire length.[70]

Antioxidant content, measured by the lag time for oxidation of cholesterol, is improved by the cold-water steeping of varieties of tea.[11]

Black tea

In the West, water for black tea is usually added near the boiling point of water, at around 99 °C (210 °F). Many of the active substances in black tea do not develop at temperatures lower than 90 °C (194 °F).[citation needed] Lower temperatures are used for some more delicate teas. The temperature will have as large an effect on the final flavour as the type of tea used. The most common fault when making black tea is to use water at too low a temperature. Since boiling point drops with increasing altitude, it is difficult to brew black tea properly in mountainous areas. It is also recommended by the British that the teapot be warmed before preparing tea, easily done by adding a small amount of boiling water to the pot, swirling briefly, then discarding it.

Western black teas are usually brewed for about four minutes and are usually not allowed to steep for less than 30 seconds or more than about five minutes (a process known as brewing or mashing in Britain). In many regions of the world, however, boiling water is used and the tea is often stewed. For example in India, black tea is often boiled for fifteen minutes or longer as a strong brew is preferred for making Masala chai. When the tea has brewed long enough to suit the tastes of the drinker, it should be strained while serving. Popular varieties of black tea include Assam, Nepal, Darjeeling, Nilgiri, Turkish and Ceylon teas.

Green tea

Water for green tea, according to regions of the world that prefer mild tea, should be around 80 to 85 °C (176 to 185 °F); the higher the quality of the leaves, the lower the temperature. Hotter water will produce a bitter taste. However, this is the method used in many regions of the world, such as North Africa or Central Asia, where bitter tea is appreciated. For example, in Morocco, green tea is steeped in boiling water for 15 minutes. In the West and Far East, a milder tea is appreciated. The container in which the tea is steeped, the mug or teapot, is often warmed beforehand so the tea does not immediately cool down. High-quality green and white teas can have new water added as many as five or more times, depending on variety, at increasingly higher temperatures.

Oolong tea

Oolong teas should be brewed around 80 to 100 °C (176 to 212 °F), and the brewing vessel should be warmed before pouring in the water. Yixing purple clay teapots are the traditional brewing-vessel for oolong tea. For best results, spring water should be used as the minerals in spring water tend to bring out more flavour in the tea. High-quality oolong can be brewed multiple times from the same leaves, and unlike green tea, it improves with reuse. It is common to brew the same leaves three to five times, the third steeping usually considered the best. In the Chinese and Taiwanese Gongfu tea ceremony, the first brew is not drunk at all but disposed of as it is considered a wash of the leaves rather than a proper brew.

Premium or delicate tea

Some teas, especially green teas and delicate oolong teas, are steeped for shorter periods, sometimes less than 30 seconds. Using a tea strainer separates the leaves from the water at the end of the brewing time if a tea bag is not being used. However, the black Darjeeling tea, a premium Indian tea, needs a longer than average steeping time. Elevation and time of harvest offer varying taste profiles; proper storage and water quality also have a large impact on taste.

Pu-erh tea

Pu-erh teas require boiling water for infusion. Some prefer to quickly rinse pu-erh for several seconds with boiling water to remove tea dust which accumulates from the ageing process, then infuse it at the boiling point (100 °C or 212 °F), and allow it to steep from 30 seconds to five minutes.

Serving

To preserve the pretannin tea without requiring it all to be poured into cups, a second teapot may be used. The steeping pot is best unglazed earthenware; Yixing pots are the best known of these, famed for the high-quality clay from which they are made. The serving pot is generally porcelain, which retains the heat better. Larger teapots are a post-19th century invention, as tea before this time was very rare and very expensive. Experienced tea-drinkers often insist the tea should not be stirred around while it is steeping (sometimes called winding or mashing in the UK). This, they say, will do little to strengthen the tea, but is likely to bring the tannins out in the same way that brewing too long will do. For the same reason, one should not squeeze the last drops out of a teabag; if stronger tea is desired, more tea leaves should be used.

Additives

The addition of milk to tea in Europe was first mentioned in 1680 by the epistolist Madame de Sévigné.[72] Many teas are traditionally drunk with milk in cultures where dairy products are consumed. These include Indian masala chai and British tea blends. These teas tend to be very hearty varieties of black tea which can be tasted through the milk, such as Assams, or the East Friesian blend. Milk is thought to neutralise remaining tannins and reduce acidity.[73][74] The Han Chinese do not usually drink milk with tea but the Manchus do, and the elite of the Qing Dynasty of the Chinese Empire continued to do so. Hong Kong-style milk tea is based on British colonial habits. Tibetans and other Himalayan peoples traditionally drink tea with milk or yak butter and salt. In Eastern European countries (Russia, Poland and Hungary) and in Italy, tea is commonly served with lemon juice. In Poland, tea with milk is called a bawarka ("Bavarian style"), and is often drunk by pregnant and nursing women. In Australia, tea with milk is white tea.

The order of steps in preparing a cup of tea is a much-debated topic, and can vary widely between cultures or even individuals. Some say it is preferable to add the milk before the tea, as the high temperature of freshly brewed tea can denature the proteins found in fresh milk, similar to the change in taste of UHT milk, resulting in an inferior-tasting beverage.[75] Others insist it is better to add the milk after brewing the tea, as most teas need to be brewed as close to boiling as possible. The addition of milk chills the beverage during the crucial brewing phase, if brewing in a cup rather than using a pot, meaning the delicate flavour of a good tea cannot be fully appreciated. By adding the milk afterwards, it is easier to dissolve sugar in the tea and also to ensure the desired amount of milk is added, as the colour of the tea can be observed.[citation needed] Historically, the order of steps was taken as an indication of class: only those wealthy enough to afford good-quality porcelain would be confident of its being able to cope with being exposed to boiling water unadulterated with milk.[76] Higher temperature difference means faster heat transfer so the earlier you add milk the slower the drink cools.

A 2007 study published in the European Heart Journal found certain beneficial effects of tea may be lost through the addition of milk.[77]

Many flavourings are added to varieties of tea during processing. Among the best known are Chinese jasmine tea, with jasmine oil or flowers, the spices in Indian masala chai, and Earl Grey tea, which contains oil of bergamot. A great range of modern flavours have been added to these traditional ones. In eastern India, people also drink lemon tea or lemon masala tea. Lemon tea simply contains hot tea with lemon juice and sugar. Masala lemon tea contains hot tea with roasted cumin seed powder, lemon juice, black salt and sugar, which gives it a tangy, spicy taste. Adding a piece of ginger when brewing tea is a popular habit of Sri Lankans, who also use other types of spices such as cinnamon to sweeten the aroma.

Other popular additives to tea by the tea-brewer or drinker include sugar, liquid honey or a solid Honey Drop, agave nectar, fruit jams, and mint. In China, sweetening tea was traditionally regarded as a feminine practice. In colder regions, such as Mongolia, Tibet and Nepal, butter is added to provide necessary calories. Tibetan butter tea contains rock salt and dre, a butter made from yak milk, which is churned vigorously in a cylindrical vessel closely resembling a butter churn. The same may be said for salt tea, which is popular in the Hindu Kush region of northern Pakistan.

Alcohol, such as whisky or brandy, may also be added to tea.

The flavour of the tea can also be altered by pouring it from different heights, resulting in varying degrees of aeration. The art of high-altitude pouring is used principally by people in Northern Africa (e.g. Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Libya and Western Sahara), but also in West Africa (e.g. Guinea, Mali, Senegal) and can positively alter the flavour of the tea, but it is more likely a technique to cool the beverage destined to be consumed immediately. In certain cultures, the tea is given different names depending on the height from which it is poured. In Mali, gunpowder tea is served in series of three, starting with the highest oxidisation or strongest, unsweetened tea (cooked from fresh leaves), locally referred to as "strong like death", followed by a second serving, where the same tea leaves are boiled again with some sugar added ("pleasant as life"), and a third one, where the same tea leaves are boiled for the third time with yet more sugar added ("sweet as love"). Green tea is the central ingredient of a distinctly Malian custom, the "Grin", an informal social gathering that cuts across social and economic lines, starting in front of family compound gates in the afternoons and extending late into the night, and is widely popular in Bamako and other large urban areas.

In Southeast Asia, particularly in Singapore and Malaysia, the practice of pouring tea from a height has been refined further using black tea to which condensed milk is added, poured from a height from one cup to another several times in alternating fashion and in quick succession, to create a tea with entrapped air bubbles creating a frothy "head" in the cup. This beverage, teh tarik, literally, "pulled tea" (which has its origin as a hot Indian tea beverage), has a creamier taste than flat milk tea and is extremely popular in the region. Tea pouring in Malaysia has been further developed into an art form in which a dance is done by people pouring tea from one container to another, which in any case takes skill and precision. The participants, each holding two containers, one full of tea, pour it from one to another. They stand in lines and squares and pour the tea into each other's pots. The dance must be choreographed to allow anyone who has both pots full to empty them and refill those of whoever has no tea at any one point.

Economics

Tea is the most popular manufactured drink in the world in terms of consumption. Its consumption equals all other manufactured drinks in the world – including coffee, chocolate, soft drinks, and alcohol – put together.[4] Most tea consumed outside East Asia is produced on large plantations in the hilly regions of India and Sri Lanka, and is destined to be sold to large businesses. Opposite this large-scale industrial production are many small "gardens," sometimes minuscule plantations, that produce highly sought-after teas prized by gourmets. These teas are both rare and expensive, and can be compared to some of the most expensive wines in this respect.

India is the world's largest tea-drinking nation,[78] although the per capita consumption of tea remains a modest 750 grams per person every year. Turkey, with 2.5 kg of tea consumed per person per year, is the world's greatest per capita consumer.[79]

Production

In 2003, world tea production was 3.21 million tonnes annually.[80] In 2010, world tea production reached over 4.52 million tonnes after having increased by 5.7% between 2009 and 2010.[81] Production rose by 3.1% between 2010 and 2011. The largest producers of tea are the People's Republic of China, India, Kenya, Sri Lanka, and Turkey.

The following table shows the amount of tea production (in tonnes) by leading countries in recent years. Data are generated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations as of February 2012.[80]

| Rank | Country[80] | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,274,984 | 1,375,780 | 1,467,467 | 1,640,310 | |

| 2 | 987,000 | 972,700 | 991,180 | 1,063,500 | |

| 3 | 345,800 | 314,100 | 399,000 | 377,912 | |

| 4 | 318,700 | 290,000 | 282,300 | 327,500 | |

| 5 | 198,046 | 198,601 | 235,000 | 221,600 | |

| 6 | 173,500 | 185,700 | 198,466 | 206,600 | |

| 7 | 165,717 | 165,717 | 165,717 | 162,517 | |

| 8 | 150,851 | 146,440 | 150,000 | 142,400 | |

| 9 | 80,142 | 71,715 | 88,574 | 96,572 | |

| 10 | 96,500 | 86,000 | 85,000 | 82,100 | |

| Total | World | 4,211,397 | 4,242,280 | 4,518,060 | 4,321,011 |

Certification

Workers who pick and pack tea on plantations in developing countries can face harsh working conditions and can earn below the living wage.[82]

A number of bodies independently certify the production of tea. Tea from certified estates can be sold with a certification label on the pack. The most important[according to whom?] certification schemes are Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, UTZ Certified, and Organic. All these schemes certify other crops (such as coffee, cocoa and fruit), as well. Rainforest Alliance certified tea is sold by Unilever brands Lipton and PG Tips in Western Europe, Australia and the US. Fairtrade certified tea is sold by a large number of suppliers around the world. UTZ Certified announced a partnership in 2008 with Sara Lee brand Pickwick tea.

Production of organic tea has risen since its introduction in 1990 at Rembeng, Kondoli Tea Estate, Assam.[83] 6,000 tons of organic tea were sold in 1999.[84] About 75% of organic tea production is sold in France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States.[citation needed]

Trade

According to the FAO in 2007, the largest importer of tea, by weight, was the Russian Federation, followed by the United Kingdom, Pakistan, and the United States.[85] Kenya, China, India and Sri Lanka were the largest exporters of tea in 2007 (with exports of: 374229, 292199, 193459 and 190203 tonnes respectively).[85][86] The largest exporter of black tea in the world is Kenya, while the largest producer (and consumer) of black tea in the world is India.[86][87]

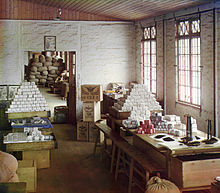

Packaging

Tea bags

In 1907, American tea merchant Thomas Sullivan began distributing samples of his tea in small bags of Chinese silk with a drawstring. Consumers noticed they could simply leave the tea in the bag and reuse it with fresh tea. However, the potential of this distribution/packaging method would not be fully realised until later on. During World War II, tea was rationed in the United Kingdom. In 1953 (after rationing in the UK ended), Tetley launched the tea bag to the UK and it was an immediate success.

Tea leaves are packed into a small envelope (usually composed of paper) known as a tea bag. The use of tea bags is easy and convenient, making them popular for many people today. However, the use of tea bags has negative aspects, as well. The tea used in tea bags is commonly fannings or "dust", the waste product produced from the sorting of higher-quality loose leaf tea. However, this is not true for all brands of tea; many high-quality speciality teas are available in bag form.[citation needed] Tea aficionados commonly believe this method provides an inferior taste and experience. The paper used for the bag may also be tasted, which can detract from the tea's own flavour.[citation needed] Because fannings and dust are a lower quality of the tea to begin with, the tea found in tea bags is less finicky when it comes to brewing time and temperature.

Additional reasons why bag tea is considered less well-flavoured include:

- Dried tea loses its flavour quickly on exposure to air. Most bag teas (although not all) contain leaves broken into small pieces; the great surface area to volume ratio of the leaves in tea bags exposes them to more air, and therefore causes them to go stale faster. Loose tea leaves are likely to be in larger pieces, or to be entirely intact.[citation needed]

- Breaking up the leaves for bags extracts flavoured oils.[citation needed]

- The small size of the bag does not allow leaves to diffuse and steep properly.[citation needed]

The "pyramid tea bag" (or sachet) introduced by Lipton[88] and PG Tips/Scottish Blend in 1996,[89] attempts to address one of the connoisseurs' arguments against paper tea bags by way of its three-dimensional tetrahedron shape, which allows more room for tea leaves to expand while steeping.[citation needed] However, some types of pyramid tea bags have been criticised as being environmentally unfriendly, since their synthetic material is not as biodegradable as loose tea leaves and paper tea bags.[90]

Loose tea

The tea leaves are packaged loosely in a canister, paper bag, or other container such as a tea chest. Some whole teas, such as rolled gunpowder tea leaves, which resist crumbling, are sometimes vacuum packed for freshness in aluminised packaging for storage and retail. The loose tea must be individually measured by the consumer for use in a cup, mug, or teapot. This allows for flexibility and flavor control, letting the consumer brew weaker or stronger tea as desired, but some convenience is sacrificed compared to newer methods such as tea bags. Strainers, tea balls, tea presses, filtered teapots, and infusion bags can be used to prevent loose leaves from floating in the tea and over-brewing. A more traditional way around this problem is to use a three-piece lidded teacup, called a gaiwan. The lid of the gaiwan can be tilted to decant the leaves while pouring the tea into a different cup for consumption. Alternatively, some tea infusers, sized for a single person and resembling a small metal basket on the end of a spoon's handle, may be used to brew one cup of tea at a time.

Compressed tea

Some teas (particularly Pu-erh tea) are still compressed for transport, storage, and ageing convenience. The tea brick remains in use in the Himalayan countries or Mongolian steppes. The tea is prepared and steeped by first loosening leaves off the compressed cake using a small knife. Compressed teas can usually be stored for longer periods of time without spoilage when compared with loose leaf tea.

Instant tea

In recent times, "instant teas" are becoming popular, similar to freeze-dried instant coffee. Similar products also exist for instant iced tea, due to the convenience of not requiring boiling water. Instant tea was developed in the 1930s, but not commercialised until later. Nestlé introduced the first instant tea in 1946, while Redi-Tea introduced the first instant iced tea in 1953.

These products often come with added flavours, such as chai, vanilla, honey or fruit, and may also contain powdered milk. Tea connoisseurs tend to criticise these products for sacrificing the delicacies of tea flavour in exchange for convenience.

British and Canadian soldiers during the Second World War were issued with an instant tea, known as 'Compo' tea. The blocks of instant tea (which included powdered milk and sugar) were issued in a Composite Ration Pack, hence the name 'Compo'. As Royal Canadian Artillery Gunner, George C Blackburn noted, it was not always well received:

But, unquestionably, the feature of Compo rations destined to be remembered beyond all others is Compo tea...Directions say to "sprinkle powder on heated water and bring to the boil, stirring well, three heaped teaspoons to one pint of water."

Every possible variation in the preparation of this tea was tried, but...it always ended up the same way. While still too hot to drink, it is a good-looking cup of strong tea. Even when it becomes just cool enough to be sipped gingerly, it is still a good-tasting cup of tea, if you like your tea strong and sweet. But let it cool enough to be quaffed and enjoyed, and your lips will be coated with a sticky scum that forms across the surface, which if left undisturbed will become a leathery membrane that can be wound around your finger and flipped away...[91]

Bottled and canned tea

Switzerland is considered the motherland of bottled iced tea. Maks Sprengler, a Swiss businessman, tried the famous American iced tea and was the first to suggest producing ready-made iced tea in bottles. In 1983, Bischofszell Food Ltd. became the first producer in the world of bottled ice tea on an industrial scale.[92]

Canned tea is a form of tea that has already been prepared, and is sold ready to drink. Canned tea is a fairly recent innovation, first launched in 1981 in Japan.

Storage

Tea shelf life varies with storage conditions and type of tea. Black tea has a longer shelf life than green tea. An exception, pu-erh tea, improves with age. Tea stays freshest when stored in a dry, cool, dark place in an air-tight container. Black tea stored in a bag inside a sealed opaque canister may keep for two years. Green tea loses its freshness more quickly, usually in less than a year. Gunpowder tea, its leaves being tightly rolled, keeps longer than the more open-leafed Chun Mee tea. Storage life for all teas can be extended by using desiccant packets, oxygen-absorbing packets, vacuum sealing or store tea in closed containers in a refrigerator.

When storing green tea, discreet use of refrigeration or freezing is recommended. In particular, drinkers need to take precautions against temperature variation.[93]

Improperly stored tea may lose flavour, acquire disagreeable flavours or odors from other foods, or become moldy.

Gallery

-

Da Hong Pao tea, an oolong tea

-

Fuding Bai Hao Yinzhen tea, a white tea

-

Green pu-erh tuo cha, a type of compressed raw pu-erh

-

Huoshan Huangya tea, a yellow tea

-

Loose dried tea leaves

-

Taiwanese High Mountain oolong

-

A spicy Thai salad made with young, fresh tea leaves

See also

References

- ^ Fuller, Thomas (21 April 2008). "A Tea From the Jungle Enriches a Placid Village". The New York Times. New York. p. A8.

- ^ a b Tea. Encarta. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- ^ Martin, p. 8

- ^ a b Alan Macfarlane (2004). The Empire of Tea. The Overlook Press. p. 32. ISBN 1-58567-493-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Penelope Ody, (2000). Complete Guide to Medicinal Herbs. New York, NY: Dorling Kindersley Publishing. p. 48. ISBN 0-7894-6785-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c Mary Lou Heiss; Robert J. Heiss (23 March 2011). The Story of Tea: A Cultural History and Drinking Guide. Random House. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-60774-172-5.

By the time of the Shang dynasty (1766–1050 BC), tea was being consumed in Yunnan Province for its medicinal properties

- ^ a b Bennett Alan Weinberg; Bonnie K. Bealer (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Psychology Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-415-92722-2.

The Portuguese traders and the Portuguese Jesuit priests, who like Jesuits of every nation busied themselves with the affairs of caffeine, wrote frequently and favorably to compatriots in Europe about tea.

- ^ a b c Colleen Taylor Sen (2004). Food Culture in India. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-313-32487-1.

Ironically, it was the British who introduced tea drinking to India, initially to anglicized Indians... tea did not become a mass drink in India until the 1950s when the India Tea Board, faced with a surplus of low-grade tea, launched an advertising campaign to popularize tea in the North, where the drink of choice was milk.

- ^ Heinrich, Ulrike (27 April 2011). "Green Tea Polyphenols Provide Photoprotection, Increase Microcirculation, and Modulate Skin Properties of Women". J. Nutr. 141 (6): 1202–1208. doi:10.3945/jn.110.136465. PMID 21525260.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16582024, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16582024instead. - ^ a b c Korte, G.; et al. (2010). "Tea catechins'affinity for human cannabinoid receptors" (PDF). Phytomedicine. 17 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2009.10.001. PMID 19897346. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) Cite error: The named reference "urlmissclasses.com" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Tomata Y, Kakizaki M, Nakaya N; et al. (2012). "Green tea consumption and the risk of incident functional disability in elderly Japanese: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 95 (3): 732–9. doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.023200. PMC 3278248. PMID 22277550.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Large-Scale, Long-Term Studies Support Roles of Physical Activity and Diet in Dementia and Cognitive Decline". Alzheimer's Association. 2010. Retrieved 24 September 2010.

- ^ a b Nobre, AC; Rao, A; Owen, GN (2008). "L-theanine, a natural constituent in tea, and its effect on mental state" (PDF). Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition. 17 Suppl 1: 167–8. PMID 18296328.

- ^ a b c d "Camellia Sinensis". Purdue University Center for New Crops and Plants Products. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- ^ Levin, Angela (20 May 2013). "Welcome to Tregothnan, England's only tea estate". The Telegraph. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ "Tea" (PDF). The Compendium of Washington Agriculture. Washington State Commission on Pesticide Registration. 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Turner, Robin (3 October 2009). "Duo plant tea in Wales". Wales Online. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ Rolfe, Jim (2003). Camellias: A Practical Gardening Guide. Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-577-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pruess, Joanna (2006). Tea Cuisine: A New Approach to Flavoring Contemporary and Traditional Dishes. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-741-7.

- ^ a b Mondal, T.K. (2007). "Tea". In Pua, E.C.; Davey, M.R. (eds.). Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry. Vol. 60: Transgenic Crops V. Berlin: Springer. pp. 519–520. ISBN 3-540-49160-0.

- ^ Britannica Tea Cultivation. Retrieved June 2007.

- ^ Elizabeth S. Hayes (1980). Spices and Herbs: Lore and Cookery. Courier Dover Publications. p. 74. ISBN 0-486-24026-6.

- ^ Tea Guardian. "Categorization of Teas". Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Tea Guardian. "Wuyi Oolongs: Tasting, Health & Market Notes". Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ "Tea types and tea varieties". Starchefs.com. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Hamza Nassrallah (2 January 2009). "Which Tea is Healthiest?". Wonders of Tea. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Lee, KW; Lee, HJ; Lee, CY (2002). "Antioxidant Activity of Black Tea vs. Green Tea". Journal of Nutrition. 132 (4): 785. PMID 11925478.

- ^ "Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) of Selected Foods – 2007". Webcitation.org. 23 May 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2009.

- ^ Weinberg, Bennett Alan and Bealer, Bonnie K. (2001). The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World's Most Popular Drug. Routledge. p. 228. ISBN 0-415-92722-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hicks, M. B.; Hsieh, Y-H. P. and Bell, L. N. (1996). "Tea preparation and its influence on methylxanthine concentration" (PDF). Food Research International. 29 (3–4): 325–330. doi:10.1016/0963-9969(96)00038-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Graham, HN (1992). "Green tea composition, consumption, and polyphenol chemistry". Preventive medicine. 21 (3): 334–50. PMID 1614995.

- ^ "Fluoride in Tea". I-sis.org.uk. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00187-0, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/S0269-7491(98)00187-0instead. - ^ Wheeler, Steven R. (6 April 1979). "Tea and Tannins". Science. 204 (4388): 6. doi:10.1126/science.432626.

- ^ a b Yee, L. K., Tea’s Wonderful History, The Chinese Historical and Cultural Project, retrieved 17 June 2013,

year 1996-2012

- ^ Yamamoto, T; Kim, M; Juneja, L R (1997). Chemistry and Applications of Green Tea. CRC Press. p. 4. ISBN 0849340063.

For a long time, botanists have asserted the dualism of tea origin from their observations that there exist distinct differences in the morphological characteristics between Assamese varieties and Chinese varieties... Hashimoto and Shimura reported that the differences in the morphological characteristics in tea plants are not necessarily the evidence of the dualism hypothesis from the researches using the statistical cluster analysis method. In recent investigations, it has also been made clear that both varieties have the same chromosome number (n=15) and can be easily hybridised with each other. In addition, various types of intermediate hybrids or spontaneous polyploids of tea plants have been found in a wide area extending over the regions mentioned above. These facts may prove that the place of origin of Camellia sinensis is in the area including the northern part of the Burma, Yunnan, and Sichuan districts of China.

- ^ The History of Tea – Tea Bags and Makers. Inventors.about.com (9 April 2012). Retrieved on 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Tea". The Columbia Encyclopedia Sixth Edition.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Martin, p. 29: "beginning in the third century CE, references to tea seem more credible, in particular those dating to the time of Hua T'o, a highly respected physician and surgeon"

- ^ http://www.tea.co.uk/page.php?id=98#masses

- ^ Lysaght, Patricia (1987). "When I makes Tea, I makes Tea: the case of Tea in Ireland". Ulster Folklife. 33: 48–49.

- ^ Sarah Rose (2010). For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World's Favorite Drink and Changed History. Penguin Books. pp. 1–5, 89, 122, 197.

- ^ a b c Khan, Naghma, Mukhtar, Hasan (July 2007). "Tea polyphenols for health promotion". Life Sciences. 81 (7): 519–533. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2007.06.011. PMC 3220617. PMID 17655876.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shimizu M, Kubota M, Tanaka T, Moriwaki H (2012). "Nutraceutical approach for preventing obesity-related colorectal and liver carcinogenesis". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 13 (1): 579–95. doi:10.3390/ijms13010579. PMC 3269707. PMID 22312273.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Naveen Kakumanu, M.D., and Sudhaker D. Rao, M.B., B.S. (21 March 2013). "Skeletal Fluorosis Due to Excessive Tea Drinking". New England Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm1200995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Male tea drinkers 'may be at greater risk of prostate cancer'". BBC News. 19 June 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ Watching the World — Watchtower ONLINE LIBRARY. Wol.jw.org. Retrieved on 13 May 2013.

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19996359

- ^ Albert E. Dien (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0300074048.

- ^ Bret Hinsch (2011). The ultimate guide to Chinese tea.

- ^ Nicola Salter (2013). Hot Water for Tea: An inspired collection of tea remedies and aromatic elixirs for your mind and body, beauty and soul. ArchwayPublishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-1606932476.

- ^ Peter T. Daniels, ed. (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0195079937.

- ^ a b "「茶」的字形與音韻變遷(提要)".

- ^ Keekok Lee (2008). Warp and Weft, Chinese Language and Culture. Eloquent Books. p. 97. ISBN 978-1606932476.

- ^ "Why we call tea "cha" and "te"?", Hong Kong Museum of Tea Ware

- ^ Dahl, Östen. "Feature/Chapter 138: Tea". The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Max Planck Digital Library. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- ^ "Chai". American Heritage Dictionary.

Chai: A beverage made from spiced black tea, honey, and milk. ETYMOLOGY: Ultimately from Chinese (Mandarin) chá.

- ^ a b "tea". Online Etymology Dictionary.

The Portuguese word (attested from 1550s) came via Macao; and Rus. chai, Pers. cha, Gk. tsai, Arabic shay, and Turk. çay all came overland from the Mandarin form.

- ^ a b c "Tea". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- ^ "Drinking Tea for Weight Loss?". Weight loss resources.

- ^ Burke, Andrew; Elliott, Mark; Mohammadi, Kamin and Yale, Pat (2004). Iran. Lonely Planet. pp. 75–76. ISBN 1-74059-425-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tea". Modern Marvels television (program). The History Channel. Broadcast 15 October 2010.

- ^ "Tea will be declared a national drink, says Montek". The Hindu. 21 April 2012.

- ^ "Tea to get hotter with national drink tag?". The Times Of India. 30 April 2012.

- ^ "Tea will be declared national drink: Montek Singh Ahluwalia – India – IBNLive". Ibnlive.in.com. 21 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "Evaporation of waste wash water". RGF Environmental Group, Inc. 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Groundwater Quality". U.S. Geological Survey. 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Important for infusion". Zhong Guo Cha. 2007. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ "Agony of the Leaves". Margaret Chittenden. 1999. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- ^ Turkish Statistical Institute (11 August 20113). "En çok çay ve karpuz tüketiyoruz (in Turkish)/ We consume a lot of tea and watermelon". CNN Turk. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Brief Guide to Tea". BriefGuides. 2006. Archived from the original on 22 August 2006. Retrieved 7 November 2006.

- ^ "Some tea and wine may cause cancer – tannin, found in tea and red wine, linked to esophageal cancer", Nutrition Health Review, September 22, 1990.

- ^ Tierra, Michael (1990). The Way of Herbs. Pocket Books. ISBN 0-671-72403-7.

- ^ "How to make a perfect cuppa". BBC News. 25 June 2003. Retrieved 28 July 2006.

- ^ Dubrin, Beverly (1 October 2010). Tea Culture: History, Traditions, Celebrations, Recipes & More. Charlesbridge Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-60734-363-9.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17213230, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17213230instead. - ^ Sanyal, Amitava (13 April 2008). "How India came to be the largest tea drinking nation". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. p. 12.

- ^ Euromonitor International (13 May 2013). "Turkey: Second biggest tea market in the world". Market Research World. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ a b c Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations—Production FAOSTAT. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ Agritrade Executive Brief on Tea, 2013 Retrieved 21 Feb 2014

- ^ "A Bitter Cup". War on Want. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Tocklai Tea Research Station Report

- ^ United Nations. Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (2002). Organic Agriculture and Rural Poverty Alleviation: Potential and Best Practices in Asia. United Nations Publications. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9211201381

- ^ a b Food and Agriculture Oraganization of the United Nations—Trade FAOSTAT

- ^ a b "IMPORTS: Commodities by country". Faostat.fao.org. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ Thompkins, Gwen (16 September 2009). "In Kenya, Tea Auction Steeped In Tradition, Gentility: NPR". npr.org. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ^ "Lipton Institute of Tea – Interview of Steve, Tea technology manager, Chapter: A Culture of Innovation". Lipton. 2008. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ "PG Tips – About Us". pgtips.co.uk. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ Smithers, Rebecca (2 July 2010). "Most UK teabags not fully biodegradeable, research reveals". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Blackburn, George (2012). The Guns of Normandy: A Soldier's Eye View, France 1944. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 1551994623Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Bischofszell Food Ltd". Bina.ch. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- ^ "Green Tea Storage" (PDF). Retrieved 15 July 2009.

Bibliography

Martin, Laura C. (2007). Tea: The Drink that Changed the World. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0804837244.

Further reading

- Jana Arcimovičová, Pavel Valíček (1998): Vůně čaje, Start Benešov. ISBN 80-902005-9-1 (in Czech)

- Claud Bald: Indian Tea. A Textbook on the Culture and Manufacture of Tea. Fifth Edition. Thoroughly Revised and Partly Rewritten by C. J. Harrison. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta 1940 (first edition, 1933).

- Kit Chow, Ione Kramer (1990): All the Tea in China, China Books & Periodicals Inc. ISBN 0-8351-2194-1.

- John C. Evans (1992): Tea in China: The History of China's National Drink, Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-28049-5

- Forbes, Andrew ; Henley, David (2011). China's Ancient Tea Horse Road. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN: B005DQV7Q2

- Jason Goodwin (1990). "The Gunpowder Gardens: Travels through India and China in Search of Tea." Re-issued on Kindle 2012 ASIN: B007YANR90; first published by Chatto & Windus (London) 1990; Knopf (New York) 1990; reissued by Penguin (2003).

- Harler, C. R., The Culture and Marketing of Tea. Second edition. Oxford University Press, New York and Bombay, Reprinted 1958 (First edition 1933, second edition 1956).

- Eelco Hesse (1982), Tea: The eyelids of Bodhidharma, Prism Press.

- Hobhouse, Henry (2005). "Seeds of Change: Six Plants that Transformed Mankind". Shoemaker & Hoard. ISBN 1-59376-049-3.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Karmakar, Rahul (13 April 2008). "The Singpho: The cup that jeers". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. p. 12..

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè, eds. (2000). The Cambridge World History of Food. Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-40216-6..

- Lu Yu (陆羽): Cha Jing (茶经) Translated and Introduced by Francis Ross. The Classic of Tea. Boston: Little, 1974. x, 177p. ISBN 0-316-53450-1; Reprinted: Ecco Press, 1997. ISBN 0880014164.

- Victor H. Mair and Erling Hoh. The True History of Tea. New York; London: Thames & Hudson, 2009. ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1.

- Roy Moxham (2003), Tea: Addiction, Exploitation, and Empire.

- Nye, Gideon (1850). Tea: and the tea trade Parts first and second. New York: Printed by G. W. Wood.

- Lester Packer; Choon Nam Ong; Barry Halliwell (2004): Herbal and Traditional Medicine: Molecular Aspects of Health, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8247-5436-0.

- Jane Pettigrew (2002), A Social History of Tea

- Jane Pettigrew (1999), Tea & Infusions: a connoisseur's guide. Carlton Books.

- Pettigrew, Jane & Richardson, Bruce (2005). The New Tea Companion: a guide to teas throughout the world. Benjamin Press. ISBN 0-9663478-3-8.

- James Norwood Pratt (2005), Tea Dictionary

- Stephan Reimertz (1998): Vom Genuß des Tees: Eine heitere Reise durch alte Landschaften, ehrwürdige Traditionen und moderne Verhältnisse, inklusive einer kleinen Teeschule (In German)

- Tunstall-Pedoe, M.; Tunstall-Pedoe, H. (1999). "Coffee and tea consumption in the Scottish Heart Health Study follow up: conflicting relations with coronary risk factors, coronary disease, and all cause mortality". Journal of epidemiology and community health. 53 (8): 481–487. doi:10.1136/jech.53.8.481. PMC 1756940. PMID 10562866.

- Yang CS, CS (November–December 1999). "Tea and Health". Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.). 15 (11–12): 946–949. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00190-2. PMID 10575676.

External links

Media related to Tea at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tea at Wikimedia Commons- Tea at Curlie

- Tea on In Our Time at the BBC

- The UK Tea Council – an independent non-profit making body dedicated to promoting tea

- Tea in the Arts – Judith L. Fisher, Trinity University, San Antonio

- Tea latest trade data on ITC Trade Map

Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA