Territorial era of Minnesota

Fort Snelling in 1844, by John Caspar Wild | |

| Date | 1803–1858 |

|---|---|

| Location | Midwestern United States |

The territorial era of Minnesota lasted from the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 to Minnesota's achieving statehood in 1858. The Minnesota Territory itself was formed only in 1849 but the area had a rich history well before this. Though there was a long history of European presence in the area before 19th century, it was during the 19th century that the United States began to establish a firm presence in what would become Minnesota.[1]

Many of the facets of Minnesota culture that are perceived as the area's early history in fact originated after this period. Notably, the heavy Scandinavian immigration for which the state is known, and the pioneering days chronicled by author Laura Ingalls Wilder occurred after statehood in the later 19th century. Unlike these later years, the first half of the 19th century was characterized by sparsely populated communities, harsh living conditions, and to some degree, lawlessness.

This era was a period of economic transition. The dominant enterprise in the area since the 17th century had been the fur trade. The Dakota Sioux, and later the Ojibwe, tribes hunted and gathered pelts trading with French, British, and later American traders at Grand Portage, Mendota, and other sites. This trade gradually declined during the early 19th century as demand for furs in Europe diminished. The lumber industry grew rapidly, replacing furs as the key economic resource. Grain production began to develop late during this time as an emerging economic basis as well. Saw mills, and later grain mills, around Fort Snelling and Saint Anthony Falls in east-central Minnesota became magnets for development. By the end of the era east-central Minnesota had replaced northern Minnesota as the economic center of the area.

This era was also as a period of cultural transition.[2] At the time the U.S. took possession of the region, Native Americans were by far the largest ethnic groups. Their role in the fur trade gave them a steady stream of income and significant political influence even as the French, British, and Americans asserted territorial claims on the area. French and British traders had mixed with native society in the area for many decades peacefully contributing to the society and creating new ethnic groups consisting of mixed-race peoples. As the Americans established outposts in the area and the fur trade declined, the dynamics changed dramatically. The economic influence of the Native Americans diminished and American territorial ideology increasingly sought to limit their influence. Large waves of immigration in the 1850s very suddenly changed the demographics so that within a few years the population shifted from predominantly native to predominantly people of European descent. The native and mixed-race populations continued to influence the territory's culture and politics, even at the end of the territorial era, though by the time statehood was achieved that influence was in steep decline. Heavy immigration from New England and New York led to Minnesota's being labeled the "New England of the West".

Background

During the 17th century a Native American tribe known as the Ojibwe, or Chippewa, reached Minnesota as part of a westward migration. Having come from a region around Maine, they were experienced at dealing with European traders. Tensions rose between the Ojibwe and the Santee, or Eastern Dakota, Sioux, who were dominant in the area, during the ensuing years.[3]

French exploration in Minnesota is known to have begun in the 17th century with explorers like Radisson, Groseilliers, and Le Sueur. After France signed a treaty with a number of tribes to allow trade in the area, French settlements began to appear. Trader Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut explored the western area of Lake Superior helping to advance trade and leading to the establishment of Fond du Lac (part of modern Duluth, which was named after du Lhut).[4] Roman Catholic priest Louis Hennepin, captured by the Sioux in 1680 while exploring North America with famed explorer La Salle, discovered and named Saint Anthony Falls. The next account of an expedition into Minnesota's interior was that of Captain Jonathan Carver of Connecticut who reached Saint Anthony Falls in 1766.[5][6] In the later 18th century trader Peter Pond explored the Minnesota River valley noting significant European settlement in the region in addition to the natives.[7]

Explorers searching for the fabled Northwest Passage and large inland seas in North America continued to pass through this region. Fort Beauharnois was built by the French in 1721 on Lake Pepin to facilitate exploration.[8] In the 17th century a lucrative trade developed between Native Americans who trapped animals near the Great Lakes and traders who shipped the animal furs to Europe. For two centuries this trade network was the prime economic driver in the area.[9] A notable result of this trade network was the Métis people, a mixed-race community descended from Native Americans and French traders, as well as other mixed-race peoples.[10] In particular during the latter 18th century numerous French and English traders in the Minnesota region purchased Sioux wives in order to establish kinship relationships with the Sioux so as to secure their supply of furs from the tribes.[11]

The British Hudson's Bay Company was formed in 1670 to capitalize on the Native American fur trade near Hudson Bay. The company came to dominate the North American trade in the 18th century. The North West Company of Montreal was formed in 1779 to compete with Hudson's Bay Company establishing their western headquarters and key exchange point at Grand Portage in what is now Minnesota.[8] Grand Portage, with its two wharves and numerous warehouses, became one of Britain's four main fur trading posts, along with Niagara, Detroit, and Michilimackinac.[12] British ships crossed Lake Superior regularly transporting supplies to the region and bringing back valuable furs.[13] Even after Grand Portage became property of the U.S. in 1783 the British operations, such as North West Company and the XY Company, continued to operate in the area for some time.[14]

Though the various parts of what is now Minnesota were claimed at different times by Spain, France, and Britain, none of these nations made significant efforts to establish major settlements in the area. Instead the French and the British established mostly trading posts and utilized the natives in the area as suppliers.[15]

All of the land east of the Mississippi River was granted to the United States by the Second Treaty of Paris at the end of the American Revolution in 1783. This included what would become modern day Saint Paul but only part of Minneapolis, including the northeast, north-central and east-central portions of the state. The wording of the treaty in the Minnesota area depended on landmarks reported by fur traders, who erroneously reported an "Isle Phelipeaux" in Lake Superior, a "Long Lake" west of the island, and the belief that the Mississippi River ran well into modern Canada. Much of this region was claimed by other states who subsequently ceded these to the federal government.[16]

Most of the remaining areas of what is now the state were purchased in 1803 from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase (the area west of the Mississippi having been recently acquired by France from Spain).[17] Parts of northern Minnesota were considered to be in Rupert's Land, a large territory owned by Hudson's Bay Company. The exact definition of the boundary between Minnesota and British North America was not addressed until the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.[18]

Until 1818 the entire Red River Valley in what is today southeastern Manitoba and northwestern Minnesota was considered British and was subject to several colonization schemes by the Hudson's Bay Company, particularly the Red River Colony (also known as the Selkirk Settlement) established in 1811. The valley had, in fact, been occupied by Métis since the middle of the 17th century.[19] The Red River Colony, established to supply the British fur trade, was fraught with problems from the beginning but became important in the Minnesota area's early fur trade as well as supplying many early settlers to the region.[20]

Pioneers and exploration

At the beginning of the 19th century many parts of the Minnesota area were already well traveled by British and French explorers. Though the region's population was mostly Native American, there were important British trading posts in the area with many European and mixed-race settlers, particularly in the north.[21] Grand Portage, in particular, had long been established as the major trading center for the North West Company of Montreal.[8]

David Thompson, a British fur trader for the North West Company, completed numerous surveys and maps of the North American frontier. In 1797 he completed the first known map of the Minnesota area, in what was then the Northwest Territory.[22] The Jay Treaty, however, obliged most of the British settlers to withdraw their settlements in 1796, though mixed-race peoples remained.[17]

In 1805 U.S. Lieutenant Zebulon Pike was sent by General Wilkinson, governor of the Louisiana Territory, to enforce U.S. sovereignty against British traders in the area and establish diplomatic and trading relationships with the native tribes.[23][24] He met with the Sioux leadership in central Minnesota to secure rights for the U.S. to an area near Saint Anthony Falls, which would later become the city of Saint Paul.[24] Though a treaty was signed by some leaders from the Sioux tribes, its legitimacy (including whether the Sioux understood it) was dubious and ultimately his efforts did little to establish the authority of the U.S. in the area.[25][26]

In 1817 Major Stephen H. Long of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers led a waterborne expedition from Prairie du Chien to reach Saint Anthony Falls. He documented much of the terrain today occupied by Minneapolis and Saint Paul as well as the Native American villages that existed there at the time.[27]

In 1818 the 49th parallel was established as the boundary between the United States and British North America. However, the point where the Red River crossed this line was not marked until 1823, when Stephen Long conducted a survey expedition.[28] The expedition determined, among other things, that the fur trading post of Pembina lay just inside the U.S. border.[29]

Several efforts were made to determine the source of the Mississippi River. In 1823 Italian explorer Giacomo Constantino Beltrami who had split from the Long expedition in Pembina, found Lake Julia which he believed was the source of the Mississippi River.[30] The actual source was found in 1832, when Henry Schoolcraft was guided by a group of Ojibwe headed by Ozaawindib ("Yellow Head") to a lake in northern Minnesota. Schoolcraft named it Lake Itasca, combining the Latin words veritas ("truth") and caput ("head").[31][32]

In 1835 George William Featherstonhaugh conducted a geological survey of the Minnesota River valley and wrote an account entitled A Canoe Voyage up the Minnay Sotor.[33] Joseph Nicollet scouted the area in the late 1830s accompanied by John C. Frémont, exploring and mapping the Upper Mississippi River basin, the Saint Croix River, and the land between the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers.[34]

Forts

An important facet of the British and American frontier was a system of forts built by the military. The forts provided safe shelter for soldiers and explorers on the frontier and a base of operations for expeditions, both military and commercial. The first forts in the area had been French, particularly Fort Beauharnois, built during the 18th century and later abandoned because of the French and Indian War with the British.[35] British Fort Charlotte at Grand Portage became essential to the fur trade protecting and supplying British traders as well as the area natives. This British fort operated in the area (illegally) until 1803, even after the area's becoming recognized as part of the United States.[36] Other French and British fortifications, such as Fort St. Charles, had existed in the region but had been abandoned much earlier.[37]

In 1814 the U.S. government built Fort Shelby, later rebuilt as Fort Crawford, near modern Minnesota in what is now Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.[38] Fort Crawford would play a significant role in U.S. involvement in Minnesota, particularly as the site of the First Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The first major U.S. military presence inside the boundaries of modern Minnesota was Fort Saint Anthony, later renamed Fort Snelling (after the fort's commander Josiah Snelling). The land for the fort, at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, had been acquired in 1805 by legendary explorer Zebulon Pike. When concerns mounted about the fur trade in the area, construction of the fort began in 1819 and was completed in 1825.[39] One of the missions of the fort was to mediate disputes between the Ojibwe and the Dakota tribes. Lawrence Taliaferro, an agent of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs who became an important figure in these mediations, spent 20 years at the fort, finally resigning in 1839.[40][41]

Fort Ripley was built in 1848–1849 in central Minnesota near modern Little Falls. It was built to provide a military presence on the frontier near the new Winnebago reservation created as the tribe was moved from Iowa. In addition it helped to serve as a buffer between the Dakota Sioux and the Ojibwe.[42]

Fort Ridgely was built in 1853–1854 near the Dakota reservation in southwestern Minnesota, near modern New Ulm. It was named by U.S. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis in honor of three army officers named Ridgely who had died in the Mexican–American War.[43] The fort was created to watch over the Minnesota River Valley, in addition to the larger frontier. It replaced Fort Dodge in Iowa, which was decommissioned during the same period.[44] The fort operated as a military post until 1867.[45]

Fort Abercrombie was built in 1858 on the Red River at what is now the border between Minnesota and North Dakota near modern McCauleyville. The fort had to be moved soon afterward because of flooding problems. It was created to spur settlement of the Red River Valley, protect steamboat traffic on the river, and protect wagon trains travelling to Montana.[46]

In addition to these military bases, private companies operated numerous trading posts in the region that were often referred to as "forts", though they typically had little in the way of defensive fortifications.[47]

Native Americans

Native American populations

(1849–1853)[48]Group Sub-group Population (year) Ojibwe Lake Superior 500 (1850) Saint Croix 800 (1850) Mississippi 1,100 (1850) Pillagers 1,050 (1850) Northern/Red Lake 1,200 (1850) Bois Forts 800 (1850) Dakota Sioux Mdewakanton 2,200 (1849) Wahpekute 800 (1849) Wahpetonwan 1,500 (1849) Sisseton 3,800 (1849) Yankton 3,200 (1849) Yanktonai 4,000 (1849) Teton 6,000 (1849) Others Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) 2,500 (1849) Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara 2,253 (1853)

The two main Native American tribal groups that dominated Minnesota at the time the lands were acquired by the United States were the more established Dakota Sioux, and the Ojibwe who had migrated into the area more recently.[49] The two groups fought bitter territorial wars during the 18th century. In the mid-18th century the Battle of Kathio, in which the Ojibwe defeated the Sioux, permanently established northeastern Minnesota, particularly Mille Lacs Lake, as Ojibwe territory relegating the Sioux to southern and western Minnesota.[22][50] Skirmishes between the groups continued in the 19th century including a battle near Lac Traverse in 1818, a battle near Stillwater in 1839 (the site became known as "Battle Hollow"), and another on the Yellow Medicine River in 1854.[51]

During the War of 1812 most of the Dakota and Ojibwe sided with the British though at various times some aided the Americans or took the opportunity to attack enemy tribes (a notable American loyalist was the Dakota chief Tamaha, or "Rising Moose," an admirer of Pike, who joined the U.S. army at Saint Louis).[22][52][53] Though Grand Portage was the only part of Minnesota that saw significant conflict during the war, natives throughout the region were recruited to fight further east in areas such as Green Bay. In particular the half-Dakota British captain Joseph Renville heavily recruited among the Mdewakanton branch of the Dakota Sioux including chiefs Little Crow and Wapasha.

From 1815 to 1821 employees of the Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company engaged in various territorial conflicts known as the "fur trade wars," including the famous Battle of Seven Oaks at what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba. As a result of these conflicts numerous Métis migrated from the Red River area to central and eastern Minnesota, particularly in the vicinity of Saint Paul. This "Red River Exodus" became a major source of francophone immigration into Minnesota during the territorial era.[54] The Métis and other mixed-race groups were often regarded as French Canadian "whites" rather than "Indians".[48]

By the 1820s, animal resources were in decline in the area leading to increased competition among the tribes for game and for furs to sell.[55] Collusion among the fur trading companies led to a dramatic drop in fur prices during the late 1820s causing impoverishment for many Sioux hunters.[56] The U.S. government strongly encouraged the tribes to turn from hunting to farming, trading the woodlands for the plains.[57]

Increasing territorial conflict between the Sioux and the Ojibwe on the western frontier, particularly along the Mississippi river, led the U.S. government to attempt to mediate the conflicts. President Andrew Jackson's policy toward the tribes ultimately was to either pacify them sufficiently to allow westward expansion of American settlers, or else remove the tribes from the areas in which they prevented settlement.[57] The First Treaty of Prairie du Chien (1825), among its provisions established southern Minnesota as well as much of modern North and South Dakota as the homeland of the Dakota Sioux. The Ojibwe were given northern Minnesota and much of Wisconsin. The U.S. government, though, failed to enforce the treaty agreements leading to Little Crow's pronouncement to Indian agent Taliaferro in 1829: "We made peace to please you, but if we are badly off we must blame you for causing us to give up so much of our lands to our enemies."[58]

Following an 1846 treaty, the Winnebago tribes of Iowa were relocated to the Long Prairie reservation in central Minnesota in the late 1840s establishing an important presence in the territory.[59] Because of the poor land in the new reservation the tribe subsequently negotiated a treaty in 1856 allowing them to relocate further south to Blue Earth but ceding substantial land in the process.

All of the native tribes experienced gradual disillusionment with the U.S. government because of its inability or unwillingness to honor its treaty commitments. The major leaders among the tribes were Wabasha and Little Crow among the Dakota Sioux, Flat Mouth and Hole-in-the-Day among the Ojibwe, and Winneshiek among the Winnebago.[60] The success of treaty negotiations between the U.S. and the tribes was in great part facilitated by the mixed race families such as the Faribaults and the Renvilles.[60]

The Treaty of Traverse des Sioux in 1851 gave all of the Wahpeton and Sisseton Sioux (upper Sioux) lands west of the Mississippi River to the U.S. government.[61] The Treaty of Mendota that same year ceded the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Sioux (lower Sioux) lands in southern Minnesota, requiring relocation to an area near modern Morton.[61] Both treaties, however, were amended to during the ratification process to eliminate the explicit guarantees of lands retained by the tribes. Additionally much of the promised payments was never delivered, in part because of alleged debts owed by the Sioux to the fur traders.[61]

Native American Population by Year Year Dakota Sioux Ojibwe 1805 10,165[62] 1834 8080[62] 1836 5639[62] 1839 5389[62] 1843 4812[63] 1866 7566[63]

Despite American hunger for land, the leadership in the Minnesota Territory did not actually want to remove the Sioux from the territory. Federal subsidies to the tribes were heavily siphoned by the U.S. settlements and removal of the tribes from the territory would have meant loss of this income.[64]

Increasing impoverishment among the Sioux and continued treaty violations on the part of the United States would soon lead to bloodshed. In 1857 a renegade band of Sioux led by war chief Inkpaduta attacked the community of Spirit Lake, Iowa near the Minnesota border killing between 35 and 40 "white" settlers (the event would be referred to as the Spirit Lake Massacre). They went on to attack Springfield, Minnesota (modern Jackson) killing seven before being turned back.[65] In 1862, bands of Sioux launched the Dakota War in which they were defeated. Apart from those killed in the war, 38 Dakota Sioux were killed in a mass execution in Mankato, the largest mass execution in the U.S. history. Hundreds more Sioux and settlers were killed in the State of Minnesota's subsequent eradication of the Sioux nation in Minnesota and the new Dakota Territory.[66]

Commercial enterprises

The most important commercial enterprise in the early part of the territorial era was the lucrative fur trade. At the beginning of the 19th century two British companies competed for dominance in the North American trade: Hudson's Bay Company and the North West Company. The North West company had used Grand Portage as its western headquarters along with other smaller companies that operated in the area. Grand Portage was one of the four principal British trading and shipping points furs in North America. Following the Treaty of Paris, in 1783, British operations at Grand Portage were technically illegal though the trade continued.[67] However, beginning in 1801 the North West Company began re-establishing its headquarters north of the border at the newly constructed Fort William in what is now Ontario. After 1804 Grand Portage had been reduced to a minor trading center and most traders eventually abandoned the area. In 1842, the Hudson Bay Company, which had by then absorbed the North West Company, shipped out a final band of Ojibwe who were employed by the company.[67]

Before 1816 the majority of the fur trading posts in the Minnesota area were owned by the North West Company, but by 1821 the American Fur Company, founded in 1808 by John Jacob Astor in New York, had taken over most of these.[68] As well as Grand Portage, another significant fur shipping point in Minnesota was Fort Frances in the Rainy Lake region, near modern International Falls in the far north of the state. This location became significant as it was key to multiple waterways for shipping furs to the Atlantic.[69] Both the North West Company and the American Fur Company had posts at this location. Pembina, originally part of the Red River Colony, was a significant trading post for the Hudson's Bay Company, and once it was claimed by the U.S., became for a time key to U.S. interests in the fur trade.[70] By 1830 American Fur dominated the trade within the United States because of the exclusion of British companies by the U.S. government.[67]

Beginning in the 1820s, a fur trading route developed between the Red River Colony (in modern Manitoba) and the trading posts in Minnesota, first primarily at Mendota and later at Saint Paul.[71] The system of ox cart trails came to be known as the Red River Trails and was used principally by the Métis as a way to avoid the fur trade monopoly of the Hudson's Bay Company (which had absorbed the North West Company). Though this cross-border trade was entirely illegal and violated the policies of the Hudson's Bay Company, enforcement against the trade by American and British authorities was virtually non-existent.[71] The trail system would reach its peak usage in the mid-19th century.[72] The Hudson's Bay Company continued to expand its presence north of the U.S. border establishing new posts such as Fort Alexander and Rat Portage.[73]

The fur trade was in decline by the late 1830s.[74][75] The American Fur Company went bankrupt in 1842, though the Missouri Fur Company and other operations kept the trade from collapsing entirely.[76][77] As this trade declined the lumber industry began to grow substantially in areas such as the Saint Croix Valley where valuable white pine was plentiful. New saw mills appeared in Marine and Stillwater. Lumber was typically cut during winter and sent downstream in the spring.[74] In 1848, businessman Franklin Steele built the first private sawmill on the Saint Anthony Falls (which would later become the town of Saint Anthony) opening commercial lumbering on the Mississippi River. More sawmills quickly followed.[78] Soon the Saint Croix and Mississippi Rivers in Minnesota had become major conduits for lumber headed for Saint Louis and other destinations.[74]

The first flour mill in Minnesota was built in 1823 at Fort Snelling as a retrofitting of a lumber mill.[79] The first private grain mill was built in Washington County by Samuel Bowles. Minneapolis gained its first grain mill in 1847.[80] During the 1850s grain production began to develop rapidly but Minnesota did not become a significant grain exporter until 1858.[80]

In 1823 the first steamboat, known as the Virginia, arrived at Fort Snelling carrying Indian agent Lawrence Taliaferro.[81] By the 1830s a steady, if not yet large, stream of steamboat traffic plied the river including some ships listed as ferrying "pleasure parties".[82] The first railroad to reach the Mississippi (in Illinois), the Rock Island Railroad, was completed in the 1854. The event was celebrated with sightseeing excursions from Rock Island up the Mississippi into Minnesota.[83][84] Those excursions touched off such a wave of interest in Minnesota that 56,000 tourists visited Saint Paul by steamboat in 1856.[84]

In 1849 James Goodhue began publication of the Minnesota Pioneer newspaper in Saint Paul (the paper would later be renamed the St. Paul Pioneer Press). By the time the area achieved statehood 89 newspapers had been established.[85] Information about Minnesota published in these periodicals spread throughout the United States and Europe. Advertising campaigns were launched in the northeastern U.S. and Europe to lure European settlers. These efforts met with limited success though they would become much more successful after statehood.[86]

Saint Anthony, with its scenic waterfalls, rapidly developed as a destination for tourists traveling the Mississippi on steamboats. The Winslow House, a luxury hotel overlooking the falls, was constructed in 1857. By the late 1860s Saint Anthony had become a popular summer resort for wealthy southerners.[87]

One of the major sources of income in the territory during the 1850s was U.S. government annuity payments to the Ojibwe and other tribes required by earlier treaties. These payments amounted to more than $380,000 per year on average ($13.9 million in present-day terms) compared to approximately $120,000 per year ($4.39 million in present-day terms) given to the territory itself for development. Because of corruption, and mishandling of the payments to the tribes, a great deal of the money was used directly by U.S. settlers for commercial and community development with questionable benefit to the tribes.[88] At the beginning of the Minnesota Territory, in fact, these payments were the territory's most important source of income since the fur trade was no longer as lucrative as it had once been and other exports were still negligible.[64]

Settlements

Population by Year Year U.S. citizens Natives 1848 4,500[84] 1849 4,535[89] 25,000[89] 1850 6,077[90] 1851 7,600[91] 30,400[91] 1853 40,000[92] 31,700[93] 1857 150,000[92] 1860 172,023[90]

During most of this era Native Americans outnumbered European/U.S. settlers in what is now Minnesota. Significant Dakota Sioux settlements in the Minnesota area included Kaposia, located in what is now Saint Paul before being moved by the 1837 treaty. Significant Ojibwe settlements included Misizaaga'igan (Mille Lacs) and Nagaajiwanaang (Fond du Lac), as well as the community that had developed around the Grand Portage commerce.

When the Minnesota Territory was established in 1848 the Native American settlements in the territory still rivaled the American settlements in size. According to some scholars, the Mandan/Hidatsa village of Like-a-Fishhook in what is now North Dakota, with a population of 700, was the largest settlement in the Minnesota Territory.[89] The numerous other settlements in the territory gave a total Native American population of over 25,000 in 1849 which easily outnumbered the 4535 "white" settlers.[89]

At the outset of the 19th century most of the European settlements were related to the fur trade. The largest of these settlements were trading posts established by the North West Company, particularly those at Sandy Lake, Leech Lake, and Fond du Lac.[17] Historian Grace Lee Nute has documented over 100 fur trading posts of varying sizes in the Minnesota area before statehood.[94] Most of these posts were eventually taken over by the American Fur Company. When several hundred settlers abandoned the Red River Colony in the 1820s, they entered the United States by way of the Red River Valley, instead of moving to eastern Canada or returning to Europe, adding to the Minnesota region's population.[95]

Construction on Fort Snelling began in 1820 and was finished in 1825. The Fort became a magnet for settlement in east-central Minnesota. Nearby Mendota was established during the same period and, as the regional headquarters for the American Fur Company, also drew settlement in the area soon becoming Minnesota's commercial center.[71] Many of the first stone buildings in the territory were constructed in Mendota by employees of the American Fur Company, which bought animal pelts at that location from 1825 to 1853.[96]

The logging industry spurred further development of settlements. Before railroads, lumbermen relied mostly on river transportation to bring logs to market, which made Minnesota's timber resources attractive. Towns like Marine on Saint Croix, founded as Marine Mills, and Stillwater became significant lumber centers fed by the Saint Croix River, while Winona was supplied lumber by areas in southern Minnesota and along the Mississippi and Minnesota Rivers.[97][98]

In the 1830s a group of squatters, mostly Métis from the ill-fated Red River Colony, established a camp near the fort. Because of complaints from some residents at the fort, new restrictions were placed on the squatters forcing them to move down the Mississippi River, first to a site known as Fountain Cave, and then even further downriver.[99] Pierre "Pig's Eye" Parrant, a popular moonshiner among the group, established a saloon at the new site, and the squatters named their settlement "Pig's Eye" after Parrant (later changing the name to Lambert's Landing, and finally Saint Paul after the local chapel). The location was a convenient site for a steamboat landing and by 1847 a steamboat line had established the town as a regular stop.[71][100] This attractive advantage for commerce caused the settlement to develop significantly, soon eroding Mendota's prominence.[71]

The sutler (general store operator) at Fort Snelling, Franklin Steele, who had established lumbering interests in the area, staked a claim to lands adjacent to Saint Anthony Falls following the land cessions of the 1837 Ojibwe treaty. In 1848 he built a sawmill at the falls establishing the basis of the town of Saint Anthony which grew there. John H. Stevens, an employee of Franklin Steele, pointed out that land on the west side of the falls would make a good site for future mills. Since the land on the west side was still part of the military reservation, Stevens made a deal with Fort Snelling's commander. Stevens would provide free ferry service across the river in exchange for a tract of 160 acres (0.65 km2) at the head of the falls. Stevens received the claim and built a house, the first house in Minneapolis, in 1850. Later in 1854, Stevens platted the city of Minneapolis on the west bank.[101] In 1855 the first bridge across the main channel of the Mississippi (anywhere in the nation) was built between Minneapolis and Saint Anthony.[22]

By 1851, treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. government had opened much of Minnesota to U.S. settlement. Fort Snelling was no longer a frontier outpost. Efforts to establish Minnesota as a prominent future state in the Union were swift. In 1851 territorial legislature petitioned the U.S. Congress for land to build a railroad between Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Saint Paul.[102] That same year the legislature incorporated the University of Minnesota and established its endowment (though the University would not admit students until many years later).[103]

In 1848 when the Minnesota Territory was formed there were four major "white" settlements: Saint Paul, Saint Anthony (part of modern Minneapolis), Stillwater, and Pembina (now part of North Dakota).[84] New settlements began to appear more rapidly. Mankato was established in 1852 by entrepreneurs Jackson, Johnson, and Williams.[104] Saint Peter was established in 1853 by Captain William Bigelow Dodd. New Ulm was established in 1854 by German immigrants. Rochester was established by George Head in 1854. Not all of the new settlements were established by immigrants from the eastern U.S. and Europe, though. The town of Faribault, for example, was established in 1852 by Alexander Faribault, a Minnesota native of mixed French-Canadian/Dakota ancestry.[105]

The influx of settlers in the 1850s transformed Minnesota from a sparsely populated territory of less than 10,000 "white" settlers and a significantly larger native population, to a substantial population center of over 150,000 predominantly European settlers.[90] The city of Saint Paul expanded from less than 400 people in 1848 to over 2500 in 1852 and over 10,000 in 1860.[106]

As a result of heavy immigration from New England and New York—regions where most major towns had originated as trading centers rather than political or manufacturing centers—many new settlements in Minnesota were laid out so as to heavily favor the business districts rather than the city halls or courthouses.[107] This plan and the philosophy behind it spurred the growth of economic links between the communities and with other parts of the U.S.

In 1856 the Minnesota Territory established its first Commissioner of Emigration, Eugene Burnand. Through advertisements and speeches to new immigrants to the U.S. in New York, Burnand expanded the immigration trend which later created a large German community after statehood.[108]

Society

Until the 1850s the Native American population vastly outnumbered the population of European ancestry in the area. Nevertheless, the division between "Indian" and "white" during this era was always somewhat vague. In general persons of mixed descent were considered "white" if they dressed in European clothing and adopted European customs. "Indians" were those who lived in traditional native lifestyles.[89] (Such ethnic ambiguity mostly disappeared in North America in the latter 19th century but still exists today in Latin America).[109] Even as the U.S. began to establish its authority over the region and some settlers from the U.S. began to arrive, the Native American population continued to hold significant political and social influence as a result of the fur trade.[110] As experienced hunters they were important to one of North America's major business enterprises. The decline of this trade during the later part of the era marked the decline of Native American influence.[110]

Following the 1837 treaty the Saint Croix Triangle, between the Saint Croix and Mississippi Rivers, had been opened to U.S. settlement. Still until the later establishment of the Minnesota Territory this triangle remained an island of "white" culture and settlement. The vast majority of the Minnesota area, though, was "Indian country".[89] Contemporary accounts of larger towns such as Mendota, Saint Anthony, and Saint Paul in the 1840s indicate that the majority of the population was predominantly of French and Métis ancestry.[111] Even in these communities European culture, was not strictly dominant. Commenting on Minnesota's culture of the 1840s, Governor Alexander Ramsey described the streets of Saint Paul saying that it was common to see "the blankets and painted faces of Indians, and the red sashes and mocassins of French voyageurs and half-breeds, greatly predominating over the less picturesque costume of the Anglo-American race."[112]

It is in fact likely that a very large percentage of the "white" population reported in the 1850 census was of partially Native American ancestry.[112] Many men of mixed racial ancestry became respected members of "white" society. William W. Warren, for example, was the son of an American entrepreneur (who hailed from New York before he began working in John Jacob Astor's American Fur Company) and a mixed-blood Ojibwe mother (whose father had been in the old French and British fur trade). He was educated in the East and in the early 1850s lived on the Upper Mississippi, in part working as an independent translator and Indian Agency contractor. Warren was a good writer—his newspaper articles were eventually published as the only 19th century compendium of Ojibwe history and was elected to the territorial legislature before his death from consumption.[48]

With the establishment of the Minnesota Territory in 1848 and the treaty of 1851 waves of immigrants from the U.S. and Europe came to the territory rapidly changing the demographics. Even as these changes occurred in many areas the vagueness of the racial divisions between "Indians" and "whites" persisted. As late as 1857 it was common practice in some jurisdictions for men to be allowed to vote based on whether or not they were wearing European clothing.[113] According to some observers natives at a given polling location would share a single pair of trousers each wearing them only long enough to cast a ballot.[114]

Logging and trading communities in the territory, such as International Falls, were often known as centers of lawlessness and vice.[115] Saloons were commonly the social centers of the towns with brothels and "bath houses" adding to the character of the society. These gathering places attracted trappers, traders, smugglers, and numerous others traveling through the countryside.[115]

The late 1840s and 1850s witnessed large-scale immigration from the Eastern U.S. and Europe. By 1860 approximately 80% percent of Minnesota's U.S.-born population came from New York and New England.[107] The state was in fact for a time known as the "New England of the West".[116] Maine, in particular, contributed a large number of immigrants, probably because of the large number of lumbermen in Maine and the growing lumber industry in Minnesota.[107]

By the 1850s racist ideology in Minnesota began to match the rest of the U.S. gradually erasing some earlier social norms.[117] The ruling class was composed of primarily Anglo-American Protestants.[113] Settlers from the U.S. increasingly discussed "white" inhabitants as the key to Minnesota's future with an eye toward marginalizing the role that other "inferior" races would have in the future. Author James Wesley Bond in 1853 described Minnesota before the 1850s as "a waste of woodland and prairie, uninhabited save by the different hordes of savage tribes from time immemorial."[117] Prejudices in the territory, however, were complicated.[113] As late as 1840 mulattos in Saint Paul were commonly treated as equals to others in the community with children of all races attending the same schools. By the late 1840s, however, all blacks had been completely disenfranchised. In addition they were prevented from running for office and their children were segregated in schools.[113] By contrast Irish Catholics and Native Americans who adopted European lifestyles were allowed to vote and their children were not segregated in the classrooms.[113] Paradoxically whereas Anglo-Americans generally accepted business development by African Americans, they largely opposed business development by Irish immigrants.[113]

Minnesota was a multi-lingual area throughout the era. During the earlier parts of the era French and English were widely used but Ojibwe, Sioux, and Michif (the language of the Métis) were more widespread. By the late 1850s English had grown to be the most spoken language. New immigrants, though, brought additional languages to the territory. Newspapers were published in German (Die Minnesota Deutsche Zeitung), Swedish (Minnesota Posten), and Norwegian (Folkets Rost).[118] Irish Gaelic, Czech and other languages were used in various communities as well.[119][120]

Most of the population of the region in earlier decades followed traditional tribal religious practices. However, Roman Catholicism had been known in the area long before its acquisition by the U.S. because of the many French traders who lived and intermarried there. Catholic missionary activity among the Métis expanded greatly in the early 19th century with the Catholic Church becoming particularly established in Saint Paul.[121] Protestantism was rather a much newer phenomenon though some Protestant missionaries had entered the region in the early 19th century as well.[122] The first Protestant church appeared in 1848 (Market Street Church, Saint Paul).[123][124] The waves of immigration in the 1850s, however, would rapidly make Protestants the largest religious group. Indeed, as in much of the rest of the U.S., community leaders made a deliberate effort to recruit immigrants from Protestant areas of Northern Europe in order to ensure Protestant control of the region.[125]

African Americans and slavery

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 in theory outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory including the Minnesota area.[126] The ordinance specifically stated

There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.

— Northwest Ordinance, United States Congress of the Confederation

The ordinance was nevertheless seen as ambiguous in that it did not specifically address the slaves already in the territories, and it discussed the "free" population of the territories seemingly implying that a slave population would exist. French traders in the territories, and later even American army officers (including Josiah Snelling who commanded his namesake fort), continued to hold slaves with the blessings of many in Congress.[127]

The number of African Americans in the territory during this period was quite small but not insignificant. Newcomers continued to bring slaves with them, but there were many free blacks as well, some working as servants and some as completely independent pioneers. Information about the black immigrants during the earlier periods is sparse, but records do show that most of those at Fort Snelling were slaves.[128] Records from 1850 indicate a population of 39 free blacks out of a total population of 6,077 citizens in the territory (which excluded Native American tribes).[90][128] Before the 1840s these free persons could often expect to be treated equal to other racial groups. By the time Minnesota had achieved statehood, however, blacks had been disenfranchised and schools were segregated.[113] Despite this, from the start of the Minnesota Territory in 1848 the leadership was predominantly antislavery thus ending the practice in this era.[113]

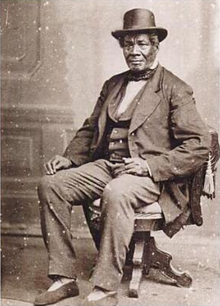

One of the most famous of the early African Americans in the territory was George Bonga.[128] He was born in Minnesota in 1802, his father Pierre Bonga the son of a freed slave and his mother a member of the Ojibwe tribe. Bonga was schooled in Montreal and eventually became a fur trader in the Northwest territories. He went on to serve as an interpreter in negotiations with the Ojibwe (particularly as a representative of Michigan Governor Lewis Cass).[128] His brother Stephen served as the Ojibwe interpreter at Fort Snelling for the 1837 treaty.[129]

In the 1850s, Fort Snelling played a key role in the infamous Dred Scott court case. Slaves Dred Scott and his wife were taken to the fort by their master, John Emerson. They lived at the fort and elsewhere in territories where slavery was prohibited. After Emerson's death, the Scotts argued that since they had lived in free territory, they were no longer slaves. Ultimately in 1857 the U.S. Supreme Court sided against the Scotts. This decision helped to fuel rancor over slavery leading to the Bleeding Kansas conflicts, the Panic of 1857, and eventually the American Civil War.[130]

Government and politics

In the earlier part of the 19th century the area which is today Minnesota was not recognized as a single entity. The Mississippi River had divided the eastern British/French lands of North America from the western Spanish lands and even after the Louisiana Purchase this was for a time seen as a separation between territories. The division between the U.S. territories in the region and the British territories remained ambiguous until the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which set the border with British North America at the 49th parallel west of the Lake of the Woods (except for a small chunk of land now dubbed the Northwest Angle). Border disputes east of the Lake of the Woods continued until the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842.[131]

Throughout the first half of the 19th century, the northeastern portion of the state was a part of the Northwest Territory, formed in 1787. After Ohio's statehood the area became part of the new Illinois Territory in 1809. After Illinois' statehood the area was incorporated into the Michigan Territory in 1818 and later became part of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. The western and southern areas of the state were not formally organized until 1838, when they became part of the Iowa Territory.[132]

Following the admission of Wisconsin as a state in 1848, the Minnesota area was temporarily without a government, though John Catlin, the former secretary of the Wisconsin Territory, claimed governorship of what remained of the territory as a short-term measure.[133] By this time Minnesota's residents were largely Democrats and, as the U.S. Congress was at that time controlled by Democrats, they hoped Congress might be sympathetic to their concerns.[134] In that same year a meeting was held in Stillwater, nominally led by Caitlin and later known as the "Stillwater Convention", to discuss establishing a new territory. The participants elected Henry Sibley as a representative to Congress.[135]

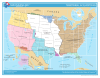

Stephen A. Douglas (D), the chair of the United States Senate Committee on Territories, drafted the bill authorizing the Minnesota Territory in 1848. He had envisioned a future for the upper Mississippi valley, so he was motivated to keep the area from being carved up by neighboring territories. In 1846, he had prevented Iowa from including Fort Snelling and Saint Anthony Falls within its northern border.[136] In 1847, he kept the organizers of Wisconsin from including Saint Paul and Saint Anthony Falls.[136] The Minnesota Territory was established from the lands remaining from Iowa Territory and Wisconsin Territory on March 3, 1849. The Minnesota Territory extended far into what is now North Dakota and South Dakota, to the Missouri River. There was a dispute over the shape of the state to be carved out of Minnesota Territory. An alternate proposal that was only narrowly defeated would have made the 46th parallel the state's northern border and the Missouri River its western border, thus giving up the whole northern half of the state in exchange for the eastern half of what later became South Dakota.[137]

Alexander Ramsey (W) became the first governor of Minnesota Territory and Henry Hastings Sibley (D) became the territorial delegate to the United States Congress. Henry M. Rice (D), who replaced Sibley as the territorial delegate in 1853, worked in Congress to promote Minnesota interests. He lobbied for the construction of a railroad connecting Saint Paul and Lake Superior, with a link from Saint Paul to the Illinois Central Railroad.[138]

Organization and statehood

(1849–1858)

Before 1856 there was minimal discussion of statehood within Minnesota. However, as discussion of a potential transcontinental railroad in the U.S. became serious, leaders in Minnesota recognized that a territory was in a weak position to lobby for this economic opportunity.[139]

In December 1856, Rice brought forward two bills in Congress: an enabling act that would allow Minnesota to form a state constitution, and a railroad land grant bill. The enabling act defined a state containing both prairie and forest lands with the boundaries drawn as they are today.[140] The bid for statehood came at a time when North–South tensions in the U.S. were rising, tensions that would later lead to the American Civil War. Debate over admitting Minnesota as a free state was heated, but the enabling act was finally passed on February 26, 1857.[141]

A constitutional convention was assembled in the territory in July 1857. Divisions between Republicans and Democrats led to the drafting of two separate constitutions. The larger cities of Saint Paul, Saint Anthony, and Stillwater were the domain of the Democrats whereas agrarian southern Minnesota was the domain of the Republicans.[142] A single constitution was finally worked out between the two factions though the more powerful Democrats ultimately prevailed on most issues.[143] The resentment between the two parties remained so acrimonious that two separate copies of the constitution had to be used so that members of each party did not have to sign a copy signed by members of the other party. The copies were signed on August 29, 1857 and an election was called on October 13, 1857 to approve the document. 30,055 voters approved the constitution, while 571 rejected it.[144]

The state constitution was sent to the United States Congress for ratification in December 1857. The approval process was drawn out for several months while Congress debated over issues that had stemmed from the Kansas–Nebraska Act. Once questions surrounding Kansas were settled the bill for Minnesota's admittance was passed.[145] The eastern half of the Minnesota Territory, under the boundaries defined by Henry Mower Rice, became the country's 32nd state on May 11, 1858.[146] The western part remained unorganized until its incorporation into the Dakota Territory on March 2, 1861.[84]

In popular culture

In 1855 Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who had never explored Minnesota himself, published The Song of Hiawatha containing many references to regions in Minnesota. The story was based on Ojibwe legends carried back east by other explorers and traders (particularly those collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft).[147]

Joseph Rolette (also known as "Jolly Joe") was a fur trader and territorial legislator of partially Métis (mixed French/Native American) ancestry who became an iconic figure known in Minnesota history for his irreverence. His most famous escapade was one in which, following the passage of a bill in 1857 which would have moved the territorial capital from Saint Paul to Saint Peter, Rolette absconded with the bill preventing it from becoming law. This and other stories were passed down for generations making Rolette as much a legend as a historical figure.[148]

The "Gopher State" moniker, by which the state today is widely known, was selected in the mid-19th century as a means to create an identity for the state. Though some believed that "Beaver State" should be selected instead as more dignified, a political cartoon featuring a gopher soon solidified "Gopher State" as the more well-known identity.[149]

See also

- American Fur Company

- History of Manitoba

- History of Winnipeg

- Hudson's Bay Company

- North West Company

- Red River Colony

- Rupert's Land

Notes

- ^ Mary Lethert Wingerd, North Country: The Making of Minnesota (University of Minnesota Press; 2010)

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 83.

- ^ "TimePieces: Ojibwe Arrive". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "TimePieces: Dakota & Ojibwe Treaty". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Atwater (1893), p. 13.

- ^ Meyer (1993), pp. 15–17.

- ^ Meyer (1993), pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c "TimePieces: North West Fur Co". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Harris (2004), p. 298.

- ^ Holmquist (1981), p. 36.

- ^ Anderson (1997), p. 67–68.

- ^ Gilman (1992), p. 72–74.

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 9.

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 10.

- ^ "Minnesota". Online Highways (Florence, Oregon). Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ Kincannon (2004), p. V 8–9

- ^ a b c Neill (1881), p. 73.

- ^ Lass (2000), p. 80.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 41.

- ^ Pritchett, John Perry (1924). "Some Red River Fur-Trade Activities" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society.

- ^ Nute (1930)

- ^ a b c d "Minnesota Chronicle". State of Minnesota. Archived from the original on December 1, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ "James Wilkinson". Army Center of Military History. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Neill (1881), p. 74–76.

- ^ Meyer (1993), p. 26–28.

- ^ "Looking at the Territory: The Treaty Story". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ Neill (1881), p. 82–85.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 46–47.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 47–48.

- ^ Neill (1881), p. 94.

- ^ "TimePieces: Mississippi Source". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary". Freelang.net. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 91–92.

- ^ "TimePieces: Upper Mississippi Maps". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Meyer (1993), p. 12.

- ^ Association of Ontario Land Surveyors (1902), p. 108.

- ^ Blegen, Theodore C. (September 1937). "Fort St. Charles and the Northwest Angle" (PDF). Minnesota History Magazine. 18 (3).

- ^ Flandrau (1900), p. 358.

- ^ Gilman (1991), p. 81–82.

- ^ Gilman (1991), p. 82–84.

- ^ "Historic Fort Snelling". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- ^ Johnson, Jack K. "History of Old Fort Ripley 1849–1877". Military Historical Society of Minnesota. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Upham (2001), p. 398.

- ^ Curtiss-Wedge (1994), p. 617.

- ^ "Fort Ridgely: Timeline". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ Carley (2001), p. 53.

- ^ Nute (1930), p. 353.

- ^ a b c Kaplan (1999), p. 30.

- ^ Blegen (1975), p. 20.

- ^ Meyer (1993), p. 13–14.

- ^ Neill (1858), p. 298–299.

"Battle between Sioux and Chippewa". Washington County Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

"MINNESOTA.; Indian Battle-- Failure of Mails". New York Times. August 14, 1854. - ^ Meyer (1993), p. 29.

- ^ Robinson (1904), p. 124.

- ^ Bumsted (2003), p. 74.

- ^ Anderson (1997), p. 130.

- ^ Anderson (1997), p. 132.

- ^ a b Anderson (1997), p. 130–131.

- ^ Anderson (1997), p. 133.

- ^ Wood, Alley, & Co. (1878), p. 79.

- ^ a b Kaplan (1999), p. 8.

- ^ a b c Blegen (1975), p. 166.

- ^ a b c d Holmquist (1981), p. 20.

- ^ a b Holmquist (1981), p. 21.

- ^ a b Lass (1998), p. 113.

- ^ "Our History". Jackson Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2009.

- ^ Fredriksen (1999), p. 444.

- ^ a b c Buck, Solon J. (1923). "The Story of the Grand Portage" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 23–25.

- ^ Nute (1930), p. 356.

- ^ "Chapter One: The Rainy Lake Region in the Fur Trade". U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2001.

- ^ Meinig (1995), p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e Gilman (1979), p. 8.

- ^ Gilman (1979), p. 14.

- ^ Wilson (2009), p. lx.

- ^ a b c "History of Inland Water Transportation in Minnesota". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ "History of Minnesota's Lake Superior". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved December 8, 2009.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 61.

- ^ Waters (1999), p. 76.

- ^ "TimePieces: Falls Power Industry". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Powers (1893), p. 165.

- ^ a b Powers (1893), p. 166.

- ^ Neill (1881), p. 93.

- ^ Minnesota Historical Society (1898), pp. 375–381.

- ^ "The Rock Island Railroad Excursion of 1854" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society.

- ^ a b c d e "History of the Minnesota Territory". Minnesota Territorial Pioneers. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved November 28, 2009.

- ^ Olson, Floyd B. (June 1933). "The Emergence of the North Star State" (PDF). Minnesota History Magazine. 14: 139.

- ^ Holmquist (1981), p. 193.

- ^ "Early St. Anthony and Minneapolis". St. Anthony Falls Heritage Board. Retrieved November 4, 2009.

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 91–92.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaplan (1999), p. 6.

- ^ a b c d "Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives: Minnesota" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ a b Moreno, Juan C. "A Brief Glance at Minnesota's History" (PDF). Office of Diversity and Inclusion, University of Minnesota Extension. Retrieved December 1, 2009. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Minnesota History: A Chronology". "Minnesota State University. Archived from the original on January 7, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ Kaplan (1999), p. 30.; this figure is specified for the early 1850s but no specific year is indicated.

- ^ Nute (1930), p. 353–385.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 114–115.

- ^ "Sibley House Historic Site". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2006.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 59.

- ^ "Winona's Early History". Winona County Historical Society (via St. Mary's University of Minnesota). Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 99

- ^ Pabis (2006), p. 106.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 70–71.

- ^ Orfield, Matthias Nordberg (March 1915). "Special Land Grants to the States with Special Reference to Minnesota". Studies in the Social Sciences (2). University of Minnesota: 151.

- ^ Johnson (1915), p. 18.

- ^ AufderHeide (1938), p. 401.

- ^ "Alexander Faribault". City of Faribault. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Sibley, Henry S. (November 10, 1852). "Description of Minnesota Territory". New York Times.

"History & Background". City of St. Paul, MN. Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2009. - ^ a b c Schmiedeler, Tom. "Civic Geometry" (PDF). Minnesota Historical Society. p. 334. Retrieved December 2, 2009.

- ^ "History of Minnesota: German Immigration". Minnesota State University – Mankato. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2009.

- ^ Madrid, Raúl L. (2012). The Rise of Ethnic Politics in Latin America. Cambridge University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9781107375819.

- ^ a b Kaplan (1999) p. 32.

- ^ Holmquist (1981), p. 39.

- ^ a b Kaplan (1999), p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Green (2007), p. x.

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 100.

- ^ a b Reid (1989), p. 87–88.

- ^ Bidwell, W.H., ed. (September–December 1851). "The Line of the Lakes". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. 24. New York: W.H. Bidwell: 202.

- ^ a b Kaplan (1999), p. 28.

- ^ Aufderheide (1938), p. 123.

- ^ Regan (2002), p. 30.

- ^ Jerabek, Esther (Winter 1972). "To Bohemia: A Czech Settler Writes from Owatonna, 1856–1858" (PDF). Minnesota History Magazine. 43: 136.

- ^ Blegen (1975), p. 151.

- ^ Blegen (1975), p. 144.

- ^ "Minnesota: A State Guide". The New Deal Network (Frank and Eleanor Roosevelt Institute). Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

- ^ Hobart (1887), p. 38.

- ^ Ziegler-McPherson (2017), p. 19

- ^ Green (2007), p. 5.

- ^ Green (2007), p. 5–8.

- ^ a b c d Spangler, Earl (1963). "The Negro in Minnesota, 1800–1865". Manitoba Historical Society.

- ^ Green (2007), p. 3.

- ^ Huston (1987), p. 12–13.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 81.

- ^ "Geography: Minnesota Territory's Borders". Minnesota Territorial Pioneers. Retrieved December 9, 2009.

- ^ Wood, Alley, & Co (1878), p. 95.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 105–106.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 104–105.

- ^ a b Risjord (2005), p. 62.

- ^ Meinig (1993), p. 439

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 75.

- ^ Risjord (2005), p. 76–77.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 124.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 122–124.

- ^ Buck (1922), p. 27.

- ^ Buck (1922), p. 29.

- ^ "Minnesota Secretary of State – History/Old Stuff". Minnesota Secretary of State. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

- ^ Lass (1998), p. 125–126.

- ^ "Journal of the Senate of the United States of America, 35th Congress, 1st Session, Tuesday, May 11, 1858, p. 436".

- ^ "TimePieces: The Song of Hiawatha". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Aby (2002), p. 83–84.

- ^ "The State of Minnesota". NState, LLC. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

References

- Aby, Anne J. (2002). The North Star State: a Minnesota history reader. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-444-6.

- Association of Ontario Land Surveyors (1902). Annual report of the Association of Ontario Land Surveyors. Toronto: Henderson & Co.

- Anderson, Gary C. (1997). Kinsmen of Another Kind: Dakota White Relations in Upper Mississippi Valley 1650–1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-353-1.

- Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the City of Minneapolis Minnesota. Vol. 1. New York: Munsell & Company.

- AufderHeide, Herman J., ed. (1938). Minnesota, a state guide. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 9781603540223.

- Blegen, Theodore Christian Blegen (1975). Minnesota: a history of the State. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3983-0.

- Buck, Solon J., ed. (1922). Minnesota history. Vol. 4. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2003). Canada's diverse peoples: a reference sourcebook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-672-5.

- Carley, Kenneth (2001). The Dakota War of 1862. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- Curtiss-Wedge, Franklyn (1916). The history of Renville County, Minnesota. Chicago: H.C. Cooper.

- Flandrau, Charles E. (1900). The History of Minnesota and Tales of the Frontier. St. Paul, MN: Pioneer Press.

- Fredriksen, John C. (1999). American military leaders: from colonial times to the present. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc. ISBN 1-57607-001-8.

- Gilman, Rhoda R.; Gilman, Carolyn; Miller, Deborah L. (1979). Red River Trails : Oxcart Routes Between St Paul and the Selkirk Settlement 1820–1870. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-133-9.

- Gilman, Carolyn; Woolworth, Alan Roland (1992). The Grand Portage story. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota History Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-270-1.

- Gilman, Rhoda R. (1991). The story of Minnesota's past. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 0-87351-267-7.

- Green, William Davis (2007). A peculiar imbalance: the fall and rise of racial equality in early Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-586-3.

- Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (2004). Geology of national parks. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt. ISBN 0-7872-9971-5.

- "Historic Fort Snelling". Minnesota Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2006.

- Hobart, Chauncey (1887). History of Methodism in Minnesota. Red Wing, MN: Red Wing Printing.

- Holmquist, June Drenning (1981). They Chose Minnesota: A Survey of the State's Ethnic Groups. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-231-2.

- Huston, James L. (1987). The Panic of 1857 and the Coming of the Civil War. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2492-5.

- Johnson, Elwin Bird (1910). Forty years of the University of Minnesota. Minneapolis, MN: General Alumni Association, University of Minnesota.

- Kaplan, Anne R.; Ziebarth, Marilyn (1999). Making Minnesota Territory, 1849–1858. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-373-9.

- Kincannon, Charles Louis, ed. (2004). Census of Population & Housing (2000): Summary Social, Economic & Housing Counts: U.S. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. ISBN 9781428985445.

- Lass, William E. (1998) [1977]. Minnesota: A History (2nd ed.). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04628-1.

- Meinig, D.W. (1993). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History. Vol. 2. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 439. ISBN 0-300-05658-3.

- Meyer, Roy Willard (1993). History of the Santee Sioux: United States Indian policy on trial. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8203-6.

- Minnesota Historical Society (1898). Collections of the Minnesota Historical Society. Vol. 8. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Neill, Edward Duffield (1858). The history of Minnesota: from the earliest French explorations to the Present Time. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co.

- Neill, Edward Duffield (1881). Minnesota explorers and pioneers from A.D. 1659 to A.D. 1858. North Star Publishing.

- Nute, Grace Lee (1930). "Posts in the Minnesota Fur-Trading Area, 1660–1855" (PDF). Minnesota History Magazine. 11.

- Pabis, George S. (2007). Daily life along the Mississippi. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33563-1.

- Powers, L. G., ed. (1893). Biennial report of the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the State of Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Regan, Ann (2002). Irish in Minnesota. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-87351-419-4.

- Reid, Robert L. (1989). Picturing Minnesota 1936–1943: Photographs From The Farm Security Administration (2nd ed.). St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-248-0.

- Risjord, Norman K. (2005). A Popular History of Minnesota. Saint Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87351-532-3.

A Popular History of Minnesota.

- Robinson, Doane (1904). A History of the Dakota or Sioux Indians. Vol. 2. South Dakota State Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-217-34024-3.

- Upham, Warren (2001). Minnesota Place Names: A Geographical Encyclopedia. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0-87351-396-8.

- Waters, Thomas F. (1987). The Superior North Shore: A Natural History of Lake Superior's Northern Lands and Waters. St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-3389-0.

- Wilson, Maggie (2009). Rainy River Lives. Omaha: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2062-1.

- Wood, Alley, & Co (1878). History of Goodhue county: including a sketch of the territory and state of Minnesota. Red Wing, MN: Wood, Alley, & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ziegler-McPherson, Christina A. (2017). Selling America: Immigration Promotion and the Settlement of the American Continent, 1607–1914. Praeger. ISBN 9781440842092.

External links

- Minnesota Territorial Pioneers

- Looking at the Territory: The Treaty Story

- First-hand accounts of life in the region