Bhagat Singh: Difference between revisions

added ref, tidy date |

→Mahatma Gandhi: added ref |

||

| Line 144: | Line 144: | ||

====Mahatma Gandhi==== |

====Mahatma Gandhi==== |

||

One of the most popular ones is that [[Mahatma Gandhi]] had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but did not.<ref name="The Sunday Tribune">{{cite news |first= V. N. |last= Datta |title= Mahatma and the Martyr |date= July 27, 2008 |url= http://www.tribuneindia.com/2008/20080727/spectrum/main1.htm |publisher= [[The Tribune]] |accessdate= October 28, 2011}}</ref> A variation of this theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed.<ref name="The Sunday Tribune"/> Gandhi's supporters<ref name="The Sunday Tribune"/> say that Gandhi did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it. Furthermore, Gandhi's supporters assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, and so Gandhi would have no reason to want him dead.<ref> {{cite news | |

One of the most popular ones is that [[Mahatma Gandhi]] had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but did not.<ref name="The Sunday Tribune">{{cite news |first= V. N. |last= Datta |title= Mahatma and the Martyr |date= July 27, 2008 |url= http://www.tribuneindia.com/2008/20080727/spectrum/main1.htm |publisher= [[The Tribune]] |accessdate= October 28, 2011}}</ref> A variation of this theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed.<ref name="The Sunday Tribune"/> Gandhi's supporters<ref name="The Sunday Tribune"/> say that Gandhi did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it. Furthermore, Gandhi's supporters assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, and so Gandhi would have no reason to want him dead.<ref> {{cite news | title = Historical Analysis: Of means and ends | date = April 14 - 27, 2001 | publisher = Frontline | url = http://www.frontline.in/fl1808/18080910.htm | work = Frontline | accessdate = November 01, 2011}}</ref> |

||

Gandhi, during his lifetime, always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's [[patriotism]]. He also said that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and, for that matter, [[capital punishment]] in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. On Singh's execution, Gandhi said, "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only."<ref>''Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.'' Ahmedabad, Navjivan. vol. 45, pp. 359-61 (Gujarati)</ref> Gandhi also once said, on capital punishment, "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life because He alone gives it."{{ |

Gandhi, during his lifetime, always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's [[patriotism]]. He also said that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and, for that matter, [[capital punishment]] in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. On Singh's execution, Gandhi said, "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only."<ref>''Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.'' Ahmedabad, Navjivan. vol. 45, pp. 359-61 (Gujarati)</ref> Gandhi also once said, on capital punishment, "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life because He alone gives it."<ref> {{cite news | first = Rajindar | last = Sachar | title = Death to the death penalty | date = May 17, 2008 | publisher = Tehelka | url = http://www.tehelka.com/story_main39.asp?filename=Op170508death_to.asp | work = Tehelka | accessdate = November 01, 2011}}</ref> |

||

Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners who were not members of his [[Satyagraha]] movement released under the [[Gandhi-Irwin Pact]].<ref name="Frontline"/> According to a report in the Indian magazine ''[[Frontline (magazine)|Frontline]]'', he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentence of Singh, [[Rajguru]] and [[Sukhdev]], including a personal visit on March 19, 1931, and in a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, pleading fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would be too late.<ref name="Frontline"/> |

Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners who were not members of his [[Satyagraha]] movement released under the [[Gandhi-Irwin Pact]].<ref name="Frontline"/> According to a report in the Indian magazine ''[[Frontline (magazine)|Frontline]]'', he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentence of Singh, [[Rajguru]] and [[Sukhdev]], including a personal visit on March 19, 1931, and in a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, pleading fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would be too late.<ref name="Frontline"/> |

||

Revision as of 14:56, 1 November 2011

Bhagat Singh ਭਗਤ ਸਿੰਘ بھگت سنگھ | |

|---|---|

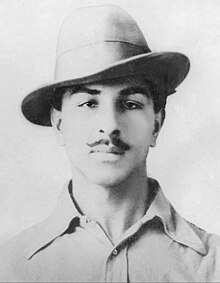

Bhagat Singh, in a western attire to avoid recognition and escape from Lahore to Calcutta. | |

| Born | September 28 1907 |

| Died | 23 March 1931[1][2] (age 23) |

| Organization(s) | Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Kirti Kisan Party, Hindustan Socialist Republican Association |

| Movement | Indian Independence movement |

Bhagat Singh (IPA: [pə̀ɡət̪ sɪ́ŋɡ] ,Template:Lang-hi, Template:Lang-pa, Template:Lang-ur September 28, 1907[7] – March 23, 1931[1][2]) was an Indian freedom fighter considered to be one of the most influential revolutionaries of the Indian independence movement. He is often referred to as Shaheed Bhagat Singh, the word shaheed meaning "martyr".

Born into a Jat Sikh family which had earlier been involved in revolutionary activities against the British Raj, as a teenager Singh studied European revolutionary movements and was attracted to anarchist and marxist ideologies.[8] He became involved in numerous revolutionary organizations, quickly rising through the ranks of the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) to become one of its leaders and was influential in changing its name to the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA).[9][10]

Singh was involved in the killing of a British police officer, John Saunders, in revenge for the death of Lala Lajpat Rai at the hands of the police, but escaped efforts by the police to capture him. He worked with Batukeshwar Dutt to bomb India's Central Legislative Assembly, and threw leaflets. Held on this charge, he gained support when he underwent a 116-day fast in jail, demanding equal rights for Indian and British political prisoners.[11] During this time, sufficient evidence was brought against him for a conviction the Saunders case, after trial by a Special Tribunal and appeal at the Privy Council in the UK. He was hanged for his participation, at the age of 23.

His legacy prompted youths in India to begin fighting for Indian independence and he continues to be a youth idol in modern India as well as the inspiration for a number of films.[12][13][14][15] He is commemorated with a large bronze statue in the Parliament of India, as well as a range of other memorials.

Early life

Bhagat Singh was born to Kishan Singh Sandhu and Vidyavati Kaur at Chak No. 105 village in the Lyallpur district of the Punjab Province in British India.[16][17] He came from a patriotic Jat Sikh family, some of whom had participated in movements supporting the independence of India and others who had served in Maharaja Ranjit Singh's army.[18] His ancestors came from the Khatkar Kalan village near the town of Banga in Nawanshahr district (now renamed as Shaheed Bhagat Singh Nagar) of Punjab. Singh's given name of Bhagat means devotee and he was nicknamed Bhaganwala by his grandmother, meaning the lucky one since the news of the release of his uncle Ajit Singh from Mandlay Jail and his father Kishan Singh from Lahore Jail coincided with his birth.[19][20] His grandfather, Arjun Singh, was a follower of Swami Dayananda Saraswati's Hindu reformist movement, Arya Samaj,[21] which had a considerable influence on Singh. His uncles, Ajit Singh and Swaran Singh, as well as his father, were members of the Ghadar Party, led by Kartar Singh Sarabha Grewal and Har Dayal. Ajit Singh was forced to flee to Persia because of pending cases against him while Swaran Singh died in 1910 at his home after releasing from Borstal Jail, Lahore.[22]

Unlike many Sikhs of his age, Singh did not attend Khalsa High School in Lahore, because his grandfather did not approve of the school officials' loyalism to the British authorities.[23] Instead, his father enrolled him in Dayanand Anglo Vedic High School, an Arya Samaj school.[24] In 1919, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre set him thinking about India's independence. In 1920, at the age of 13, Singh began to follow Mahatma Gandhi's Non-Cooperation Movement. At this point he openly defied the British and followed Gandhi's wishes by burning his government school books and any British-imported clothing. Following Gandhi's withdrawal of the movement after the violent murders of policemen by villagers from Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh in 1922, Singh, disgruntled with Gandhi's non-violent action, joined the Young Revolutionary Movement and began advocating a violent movement against the British.[25]

He was 14 when, on February 20, 1921, the custodian of Nankana Sahib (the birthplace of Guru Nanak) and his men, fired on Akali protesters. The firing was widely condemned, and an agitation was launched till the control of this historic gurudwara was restored to the Sikhs. This incident left a deep impact on him.[16]

In 1923, Singh joined National College, Lahore, where he made a positive impression, academically. He was also a member of the college dramatics society. By this time, he was fluent in Urdu, Hindi, Punjabi, English, and Sanskrit.[16][26][27] In 1923, Singh won an essay competition set by the Punjab Hindi Sahitya Sammelan. His essay, Punjab’s Language and Script, quoted Punjabi literature and discussed the problems of the Punjab,[16] and were way ahead of his age.[26] This grabbed the attention of members of the Punjab Hindi Sahitya Sammelan including its General Secretary Professor Bhim Sen Vidyalankar. He became a member of the organisation Naujawan Bharat Sabha ("Youth Society of India").[8] In the Naujawan Bharat Sabha, Singh and his fellow revolutionaries grew popular amongst the youth. He joined the Hindustan Republican Association,[28] which had prominent leaders like Ram Prasad Bismil, Chandrashekhar Azad and Ashfaqulla Khan. A year later, upon being pressurised by his family, which wanted him to get married, Singh left his house in Lahore and went to Kanpur. In a note left behind for his father, Singh said: "My life has been dedicated to the noblest cause, that of the freedom of the country. Therefore, there is no rest or worldly desire that can lure me now..."[16] It is also believed that he went to Kanpur to attempt freeing the Kakori train robbery prisoners from jail, but returned to Lahore for unknown reasons.[29] On the day of Dasara in October 1926, a bomb exploded in Lahore. Singh was arrested for his alleged involvement in this Dasara Bomb Case on May 29, 1927,[30] but was let off for good behaviour against a heavy security of Rs 60,000,[16] after about five weeks of his arrest.[31][32] He wrote for and edited Urdu and Punjabi newspapers published from Amritsar.[33] In September 1928, a meeting of various revolutionaries from across India was called at Delhi under the banner of the "Kirti Kissan Party". Singh was the secretary of the meet. His later revolutionary activities were carried out as a leader of this association.[34]

Later revolutionary activities

Lala Lajpat Rai's death and the Saunders murder

The British government created a commission under Sir John Simon to report on the current political situation in India in 1928. The Indian political parties boycotted the commission because it did not include a single Indian in its membership and it was met with protests all over the country. When the commission visited Lahore on October 30, 1928, Lala Lajpat Rai led a non-violent protest against the commission in a silent march, but the police responded with violence.[35] The superintendent of police, James A. Scott, ordered the police lathi charge against the non-violent protesters and personally assaulted Lajpat Rai, who was grievously injured. When Rai died less than three weeks later, it was widely assumed that Scott's blows had hastened his demise.[35] Singh vowed to take revenge.[36] He joined other revolutionaries, Shivaram Rajguru, Sukhdev Thapar, Jai Gopal and Chandrashekhar Azad, in a plot to kill Scott, Lahore Superintendent of Police. Jai Gopal was supposed to identify the chief and signal for Singh to shoot. However, in a case of mistaken identity, Gopal signalled Singh on the appearance of John P. Saunders, an Assistant Superintendent of Police. He was shot by Rajguru and Singh while leaving the District Police Headquarters at about 4:15 p.m. on December 17, 1928. Head Constable Chanan Singh was also killed when he came to Saunders' aid.[37][38]

Dramatic escape

After killing Saunders, they escaped through the D.A.V. College entrance, on the other side of the road. Head Constable Chanan Singh who chased them was fatally injured by Chandrashekhar Azad's covering fire. They then fled on bicycles to the prearranged places of safety. The police launched a massive search operation to catch the culprits and blocked all exits and entrances. The police sealed all roads from the city; the CID kept a watch at the railway stations and all young men leaving Lahore were scrutinized. They kept themselves underground for the next two days. Sukhdev called at the house of Durga Devi Vohra on December 19, 1928 and she agreed to help them. It was settled that they would catch the train leaving Lahore for Howrah en route Bathinda early the next morning. That train was chosen because they could leave in the early hours before the arrival of the CID picket. Singh, in Western dress and carrying the sleeping infant, Durga, in her most impressive attire, and Rajguru shuffling under luggage, left the house at about 5 a.m. long before the members of the CID arrived. On reaching the station, Singh keeping his facial profile reasonably covered on one side with a slightly raised collar of the overcoat and on the other by the sleeping infant, purchased two tickets, a joint second class Christmas return ticket and a third class one for the servant, for Cawnpur. They walked side by side into the railway station with Rajguru carrying the luggage behind in a servile manner. Both men carried concealed loaded revolvers with them in case of an untoward incident, since police parties in uniform as well as in civil clothes were carefully watching all departures from Lahore. As a respectable young couple with a child, dressed in Western style clothing and holding a joint second class Christmas return ticket, they avoided police attention. Singh and Rajguru boarded the train without causing any suspicion. To avoid recognition, Singh had shaved off his beard and cut his hair.[39] Breaking journey at Cawnpur they went to Lucknow, as the CID at Howrah kept a close watch on passengers coming directly from Lahore. At Lucknow, Rajguru left separately for Varanasi. Singh, Durga Devi and the infant went to Howrah. Durga Devi returned to Lahore a few days later.[37][40][41][42][43]

Bombs in the assembly

In the face of actions by the revolutionaries, the British government enacted the Defence of India Act to give more power to the police.[44] The purpose of the Act was to combat revolutionaries like Singh.[44] In response to this Act, the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association planned to explode a bomb in the Central Legislative Assembly where the ordinance was going to be passed. This idea was originated by Singh, who was influenced by a similar bombing by a martyr anarchist Auguste Vaillant in the French Assembly.[45] It was decided that Singh should go to Russia, while Batukeshwar Dutt should carry on the bombing with Sukhdev. Sukhdev then forced Singh to call for another meeting and here it was decided, against the initial agreement, that Batukeshwar Dutt and Singh would carry on the bombing. Singh also disapproved that the two should be escorted after the bombing by the rest of the party.[45]

On April 8, 1929, Singh and Dutt threw two bombs onto the assembly and shouted "Inquilab Zindabad!" ("Long Live the Revolution!"). This was followed by a shower of leaflets stating that it takes a loud noise to make the deaf hear.[46][47][48]The bombs did not kill anyone; Singh and Dutt claimed that this was deliberate on their part, a claim substantiated both by British forensics investigators who found that the bombs were not powerful enough to cause injury, and by the fact that the bombs were thrown away from people.[49]Singh and Dutt gave themselves up for arrest after the bombing.[49] They intended to use their court appearances as a forum for revolutionary propaganda to advocate the revolutionaries’ point of view and, in the process, rekindle patriotic sentiments in the hearts of the people. Singh surrendered his automatic pistol, the same one he had used to pump bullets into Saunders' body, knowing fully well that the pistol would be the highest proof of his involvement in the Saunders' case.[50]

On April 15, 1929, the 'Lahore Bomb Factory' was discovered by the Lahore police, and the other members of HSRA were arrested, out of which 7 turned informants, helping the police to connect Singh to the murder of Saunders. [45] Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev were charged with the murder. Singh decided to use the court as a tool to publicise his cause for the independence of India.[51] Singh was charged with attempt to murder under section 307 of the Indian Penal Code. Asaf Ali, a member of the Congress Party was his lawyer. The trial started on May 7, 1929. The Crown was represented by the public prosecutor Rai Bahadur Suryanarayan and the trial magistrate was a British Judge, P.B Pool. The prosecution’s star witness was Sergeant Terry who said that a pistol had been found on Singh’s person when he was arrested in the Assembly. This was not factually correct because Singh had himself surrendered the pistol while asking the police to arrest him. Even the eleven witnesses who said that they had seen the two throwing the bombs seemed to have been tutored. The entire incident had been so sudden that nobody could have anticipated it. The magistrate committed both of them to the Sessions Court of Judge Leonard Middleton[52]. Judge Middleton ruled that he had no doubt that the defendant's acts were 'deliberate' and rejected the plea that the bombs were deliberately low-intensity bombs since the impact of the explosion had shattered the wood of one and a half inch thickness in the Assembly. The two were persuaded to file an appeal which was rejected and they were sentenced to transportation for life (fourteen years).[37][53]

Further trial and execution

Hunger strike and Lahore conspiracy case

The police had gathered 'substantial evidence'’ against Singh and he was charged with involvement in the killings of Saunders and Head Constable Chanan Singh. The authorities had collected nearly 600 witnesses to establish their charges, which included his colleagues, Jai Gopal and Hans Raj Vohra turning government approvers. Singh was re-arrested for the murder of Saunders and the life imprisonment sentence was kept in abeyance till the outcome of the murder trial.[54]

Singh was sent to Mianwali Jail and B. Dutt to Borstal Jail in Lahore. On reaching Mianwali jail, Singh found that European prisoners got better accommodation, food and daily use items compared to Indian prisoners. While in jail, Singh and other prisoners launched a hunger strike advocating for the rights of prisoners and those facing trial.[55] The reason for the strike was that British criminals were treated better than Indian political prisoners, who, by law, were meant to be given better rights. The aims in their strike were to ensure a decent standard of food for political prisoners, the availability of books and a daily newspaper, as well as better clothing and the supply of toiletry necessities and other hygienic necessities. He also demanded that political prisoners should not be forced to do any labour or undignified work.[56][57]

As the fast progressed without any solution in sight, Jawaharlal Nehru met Singh and the other protesters. He said:

I was very much pained to see the distress of the heroes. They have staked their lives in this struggle. They want that political prisoners should be treated as political prisoners. I am quite hopeful that their sacrifice would be crowned with success.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, one of the politicians present when the Central Legislative Assembly was bombed,[59] made no secret of his sympathies for the Lahore prisoners - commenting on the hunger strike he said:

The man who goes on hunger strike has a soul. He is moved by that soul, and he believes in the justice of his cause...however much you deplore them and however much you say they are misguided, it is the system, this damnable system of governance, which is resented by the people

The Government tried several tricks to break the strike. They placed dishes of different types of food in the prison cells to test the resolve of the strikers. Water pitchers were filled with milk so that either the prisoners remained thirsty or broke their strike. But nobody faltered. The authorities attempted forced-feeding, but were resisted. One of the prisoners, Kasuri, swallowed red pepper and drank hot water to clog the feeding tube.[61] The Governor came down from Shimla to meet the jail authorities. There was no breakthrough.[62]

When the Government realized that this fast had riveted the attention of the people throughout the country, it decided to hurry up the trial, which came to known as the Lahore Conspiracy Case. This trial started in Borstal Jail, Lahore, on July 10, 1929. Rai Sahib Pandit Sri Kishen, a first class magistrate, was the judge for this trial. Singh and twenty-seven others were charged with murder, conspiracy and wagering war against the King. A handcuffed Singh, still on hunger strike, had to be brought to the court in a stretcher and his weight had fallen by 14 pounds, from 133 to 119.[63] By then, the condition of Jatindra Nath Das, who was lodged in the same jail and was also on hunger strike, had deteriorated considerably. The jail committee recommended his unconditional release, but the government rejected the suggestion and offered to release him on bail. Jatin died on September 13, 1929. His fast lasted 63 days. After his death, the Viceroy informed London:

Jatin Das of the Conspiracy Case, who was on hunger strike, died this afternoon at 1 p.m. Last night, five of the hunger strikers gave up their hunger strike. So there are only Bhagat Singh and Dutt who are on strike ...

The highest tributes were paid by almost every leader in the country. Mohammad Alam and Gopi Chand Bhargava resigned from the Punjab Legislative Council in protest. Motilal Nehru proposed the adjournment of the Central Assembly as a censure against the inhumanity of the Lahore prisoners. The censure motion was carried by 55 votes against 47.[65]

The Jail Committee requested him to give up his hunger strike and finally it was his father who had his way, armed with a resolution from the Congress party urging them to give up their strike; and it was on the 116th day of their fast, on October 5, 1929 that Singh and Dutt gave up their strike (surpassing the 97 day world record for hunger strikes which was set by an Irish revolutionary). During this hunger strike that lasted 116 days and ended with the British succumbing to his wishes, he gained much popularity among the common Indians. Before the strike his popularity was limited mainly to the Punjab region.[66]

Singh started refocusing on his trial. The crown was represented by the government advocate C.H.Carden-Noad and was assisted by Kalandar Ali Khan, Gopal Lal, and Bakshi Dina Nath who was the prosecuting inspector. The accused were defended by 8 different lawyers. When Jai Gopal turned approver, Verma, the youngest of the accused, hurled a slipper at him.[67] The case was ordered to be carried out without the accused or the members of the HSRA present in the court. This created an uproar amongst Singh's supporters as he could no longer publicise his views.[37][68]

Special Tribunal

The case proceeded at a snail's pace. On May 1, 1930, by declaring an emergency, the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, promulgated an Ordinance to set up a tribunal to try this case. This Special Tribunal was given the power to proceed with the case in the absence of the accused and accept death of the persons giving evidence as a benefit to the defence. The Ordinance, Lahore Conspiracy Case Ordinance No.3 of 1930, was to put an end to the proceedings pending in the magistrate’s court. The case was transferred from the court of Rai Sahib Pandit Sri Kishan to a Special Tribunal of three high court judges without any right to appeal, except to the Privy Council.[37][69] The Tribunal comprised: Justice J. Coldstream (president), Justice G. C. Hilton and Justice Agha Hyder (members)[70]

The case opened on May 5, 1930 in the stately Poonch House. On June 20, 1930, the constitution of the Special Tribunal was changed to: Justice G. C. Hilton (president), Justice Tapp and Justice Sir Abdul Qadir[71] On July 2, 1930, a habeas corpus petition was filed in the High Court challenging the very constitution of the tribunal and said that it was illegal ultra vires. According to the petition, the Viceroy did not have the power to cut short the normal legal procedure. The Government of India Act, 1915, authorized the Viceroy to promulgate an Ordinance to set up a tribunal but only when the situation demanded whereas now there was no breakdown in the law and order situation. The petition was however, dismissed as ‘premature’.[72] Carden-Noad, the government advocate elaborated on the charges which included dacoities, robbing money from banks and the collection of arms and ammunition. The evidence of G.T. Hamilton Harding, senior superintendent of police, took the court by surprise, as he said that he had filed the FIR against the accused under the instructions of the chief secretary to the government of Punjab and he did not know the facts of the case. There were five approvers in total out of which Jai Gopal, Hans Raj Vohra and P.N.Ghosh had been associated with the HRSA for a long time. It was on their stories that the prosecution relied. The tribunal depended on Section 9 (1) of the Ordinance. On July 10, 1930, it issued an order, and copies of the charges framed were served on the fifteen accused in jail, together with copies of an order intimating them that their pleas would be taken on the charges the following day. This trial was a long and protracted one, beginning on May 5, 1930, and ending on September 10, 1930. The tribunal framed charges against fifteen out of the eighteen accused. The case against B.K.Dutt was withdrawn as he had already been sentenced to transportation for life in the Assembly Bomb Case.[37][73]

On October 7, 1930, about three weeks before the expiry of its term, the tribunal delivered its judgement, sentencing Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru to death by hanging.[50][74] Others were sentenced to transportation for life and rigorous imprisonment. This judgement was a 300-page one which went into the details of the evidence and said that Singh’s participation in the Saunders’ murder was the most serious and important fact proved against him and it was fully established by evidence. The warrants for the three were marked with a black border.[37][75]

Appeal to the Privy Council

A defence committee was constituted in Punjab to file an appeal to the Privy Council against the sentence. Singh did not favour the appeal but his only satisfaction was that the appeal would draw the attention of people in England to the existence of the HSRA. In the case of Bhagat Singh vs. The King Emperor, the points raised by the appellant was that the ordinance promulgated to constitute a special tribunal for the trial was invalid. The government argued that Section 72 of the Government of India Act, 1915 gave the governor-general unlimited powers to set up a tribunal. Judge Viscount Dunedin who read the judgment dismissed the appeal.[76]

Reactions to the judgement

After the rejection of the appeal to the Privy Council, Madan Mohan Malviya filed a mercy appeal before the Viceroy on February 14, 1931.[77] The undertrials of the Chittagong Armoury Raid Case sent an appeal to Gandhi to intervene.[50] In his notes dated March 19, 1931, Lord Irwin, the Viceroy of India, recorded in the file:

While returning Gandhiji asked me if he could talk about the case of Bhagat Singh, because newspapers had come out with the news of his slated hanging on March 24th. It would be a very unfortunate day because on that day the new president of the Congress had to reach Karachi and there would be a lot of hot discussion. I explained to him that I had given a very careful thought to it but I did not find any basis to convince myself to commute the sentence. It appeared he found my reasoning weighty.

The Communist Party of England expressed its reaction to the case:

The history of this case, of which we do not come across any example in relation to the political cases, reflects the symptoms of callousness and cruelty which is the outcome of bloated desire of the imperialist government of Britain so that fear can be instilled in the hearts of the repressed people.

— The Communist Party of England, [79]

An abortive plan had been made to rescue Singh and fellow inmates of HSRA from the jail, for the purpose of which Bhagwati Charan Vohra made bombs, but died making them as they exploded accidentally.[29]

Singh also maintained the use of a diary, in which he eventually wrote 404 pages. In this diary he made numerous notes relating to the quotations and popular sayings of various people whose views he supported. Prominent in his diary were the views of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels[80]. The comments in his diary led to an understanding of the philosophical thinking of Singh.[81] While in the condemned cell, he also wrote a pamphlet entitled "Why I am an Atheist", as he was being accused of vanity by not accepting God in the face of death.[3] It is also said that he signed a mercy petition through a comrade Bijoy Kumar Sinha on March 8, 1931.[82]

Execution

Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were sentenced to death in the Lahore conspiracy case and ordered to be hanged on March 24, 1931. On March 23, 1931 at 7:30 pm, Singh was hanged[83] in Lahore Jail with his fellow comrades Rajguru and Sukhdev. The Superintendent of Police (political) Criminal Investigation Department, Punjab, at the time, wrote in his memoirs on "The Saunders Murder Case":

Normally execution took place at 8 am, but it was decided to act at once before the public could become aware of what had happened... at about 7 pm shouts of Inquilab Zindabad were heard from inside the jail. This was correctly, interpreted as a signal that the final curtain was about to drop.[84]

The Jail authorities then broke the rear wall of the Jail and secretly cremated the three martyrs under cover of darkness outside Ganda Singh Wala village, and then threw the bodies in the Sutlej[85], about 10 km from Ferozepore (about 60 km from Lahore).[86][87][88]

Criticism of the Special Tribunal

Singh's trial is an important event in the Indian history because it defied the fundamental doctrine of criminal jurisprudence. The trial was held ex-parte in breach of the principles of natural justice according to which no man shall be condemned unless he is given a hearing.[89] The Special Tribunal was a departure from the normal procedure adopted for a trial. There was no appeal except to the Privy Council located in England. The accused were absent from the court and the judgement was passed ex-parte.[90] This ordinance was never approved by the Central Assembly or the British Parliament, and it lapsed later without any legal or constitutional sanctity.[91] From the lower court to the tribunal to the Privy Council, it was a preordained judgement in flagrant violation of all tenets of natural justice and a fair and free trial.[50]

Reactions to the execution

The execution of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev were reported widely by the press, especially as they were on the eve of the annual convention of the Congress party at Karachi.[92] The New York Times reported:

A reign of terror in the city of Cawnpore in the United Provinces and an attack on Mahatma Gandhi by a youth outside Karachi were among the answers of the Indian extremists today to the hanging of Bhagat Singh and two fellow-assassins.[93]

Hartals and strikes of mourning were called.[94] The Congress party, during the Karachi session, declared:

While dissociating itself from and disapproving of political violence in any shape or form, this Congress places on record its admiration of the bravery and sacrifice of Bhagat Singh, Sukh Dev and Raj Guru and mourns with their bereaved families the loss of these lives. The Congress is of the opinion that their triple execution was an act of wanton vengeance and a deliberate flouting of the unanimous demand of the nation for commutation. This Congress is further of the opinion that the [British] Government lost a golden opportunity for promoting good-will between the two nations, admittedly held to be crucial at this juncture, and for winning over to methods of peace a party which, driven to despair, resorts to political violence. [95]

Ideals and opinions

Influences

Singh was attracted to anarchism and communism.[8] He read the teachings of Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky and Bakunin.[96][97] Singh did not believe in Gandhian philosophy and felt that Gandhian politics would replace one set of exploiters with another.[98] Singh was also an admirer of the writings of Irish revolutionary Terence MacSwiney.[99] Some of his writings like "Blood Sprinkled on the Day of Holi Babbar Akalis on the Crucifix" were influenced by the struggle of Dharam Singh Hayatpur[100].

Anarchism

From May to September, 1928, Singh serially published several articles on anarchism in Punjabi periodical Kirti.[8] He expressed concern over misunderstanding of the concept of anarchism among the public and tried to eradicate its misconception among people. He wrote, "The people are scared of the word anarchism. The word anarchism has been abused so much that even in India revolutionaries have been called anarchist to make them unpopular." As anarchism means absence of ruler and abolition of state, not absence of order, Singh explained, "I think in India the idea of universal brotherhood, the Sanskrit sentence vasudhaiva kutumbakam etc., has the same meaning." He wrote about the growth of anarchism,"the first man to explicitly propagate the theory of Anarchism was Proudhon and that is why he is called the founder of Anarchism. After him a Russian, Bakunin, worked hard to spread the doctrine. He was followed by Prince Kropotkin etc."[8]

Singh explained anarchism in the article:

The ultimate goal of Anarchism is complete independence, according to which no one will be obsessed with God or religion, nor will anybody be crazy for money or other worldly desires. There will be no chains on the body or control by the state. This means that they want to eliminate: the Church, God and Religion; the state; Private property.[8]

Marxism

Singh was also influenced by Marxism. He unambiguously stated in his last testament that the ideal for him and his comrades was "the social reconstruction on Marxist basis".[101] Indian historian K. N. Panikkar described Singh as one of the early Marxists in India.[98] From 1926, Singh studied the history of the revolutionary movement in India and abroad. In his prison notebooks, Singh used quotations from Vladmir Lenin (on imperialism being the highest stage of capitalism) and Trotsky on revolution.[8] In written documents, when asked what was his last wish, he replied that he was studying the life of Lenin and he wanted to finish it before his death.[102] Singh never joined the Communist Party of India, however.[97]

Atheism

Singh began to question religious ideologies after witnessing the Hindu-Muslim riots that broke out after Gandhi disbanded the Non-Cooperation Movement.[103] He did not understand how members of these two groups, initially united in fighting against the British, could be at each others' throats because of their religious differences. At this point, Singh dropped his religious beliefs, since he believed religion hindered the revolutionaries' struggle for independence, and began studying the works of Bakunin, Lenin, Trotsky — all atheist revolutionaries. He also took an interest in Niralamba Swami's[104] book Common Sense, which advocated a form of "mystic atheism".[105]

While in a condemned cell in 1931, he wrote a pamphlet entitled Why I am an Atheist in which he discusses and advocates the philosophy of atheism.[3] This pamphlet was a result of some criticism by fellow revolutionaries on his failure to acknowledge religion and God while in a condemned cell, the accusation of vanity was also dealt with in this pamphlet. He supported his own beliefs and claimed that he used to be a firm believer in The Almighty, but could not bring himself to believe the myths and beliefs that others held close to their hearts. In this pamphlet, he acknowledged the fact that religion made death easier, but also said that unproved philosophy is a sign of human weakness.[3] In this context he has said:

As regard the origin of God, my thought is that man created God in his imagination when he realized his weaknesses, limitations and shortcomings. In this way he got the courage to face all the trying circumstances and to meet all dangers that might occur in his life and also to restrain his outbursts in prosperity and affluence. God, with his whimsical laws and parental generosity was painted with variegated colours of imagination. He was used as a deterrent factor when his fury and his laws were repeatedly propagated so that man might not become a danger to society. He was the cry of the distressed soul for he was believed to stand as father and mother, sister and brother, brother and friend when in time of distress a man was left alone and helpless. He was Almighty and could do anything. The idea of God is helpful to a man in distress.

— Bhagat Singh, Why I am an Atheist

Death

Singh was known for his appreciation of martyrdom. His mentor as a young boy was Kartar Singh Sarabha.[12] Singh is himself considered a martyr for acting to avenge the death of Lala Lajpat Rai. In the leaflet he threw in the Central Assembly on April 9, 1929, he stated that It is easy to kill individuals but you cannot kill the ideas. Great empires crumbled while the ideas survived[106]. After engaging in studies on the Russian Revolution, he wanted to die so that his death would inspire the youth of India which in turn will unite them to fight the British Empire.

While in prison, Singh and two others had written a letter to the Viceroy asking him to treat them as prisoners of war and hence to execute them by firing squad and not by hanging. Prannath Mehta, Singh's friend, visited him in the jail on March 20, four days before his execution, with a draft letter for clemency, but he declined to sign it.[107]

Controversy

Last wish

Many believe that Bhai Randhir Singh, a revolutionary of the first Lahore Conspiracy Case and Gadhar, prison inmate, met Singh in Lahore Central Jail on October 4, 1930, when Randhir Singh was released from the jail, as mentioned in his book "Jail Chithiyan" by Randhir Singh himself. [108][109] Bangat Singh was condemned on October 7, 1930 contradicting his presence in condemned cells on the 4 October.[50] According to Randhir Singh, Singh mentioned to him, that he (Singh) had shaven "his hair and beard under pressing circumstances" and that "It was for the service of the country" that his companions "compelled him to give up the Sikh appearance" adding to it that he was ashamed.[110][111] He had expressed, as his last wish before being hanged, the desire to get amrit from Randhir Singh and to once again adorn the 5 Ks.[111][112] However, his last wish, of getting "amrit" was not granted by the British.[112] Some scholars are skeptic about this meeting as, Randhir Singh being the only source of information about sudden change in Singh's point of view towards religion casts doubts, as Singh had been a strong critic of religion.[3][113] And Singh had also mentioned towards the end of his article 'Why I am an Atheist':

Let us see how steadfast I am. One of my friends asked me to pray. When informed of my atheism, he said, “When your last days come, you will begin to believe.” I said, “No, dear sir, Never shall it happen. I consider it to be an act of degradation and demoralisation. For such petty selfish motives, I shall never pray.” Reader and friends, is it vanity? If it is, I stand for it.

— Bhagat Singh, Why I am an Atheist

Conspiracy theories

Many conspiracy theories exist regarding Singh, especially the events surrounding his death.

Mahatma Gandhi

One of the most popular ones is that Mahatma Gandhi had an opportunity to stop Singh's execution but did not.[114] A variation of this theory is that Gandhi actively conspired with the British to have Singh executed.[114] Gandhi's supporters[114] say that Gandhi did not have enough influence with the British to stop the execution, much less arrange it. Furthermore, Gandhi's supporters assert that Singh's role in the independence movement was no threat to Gandhi's role as its leader, and so Gandhi would have no reason to want him dead.[115]

Gandhi, during his lifetime, always maintained that he was a great admirer of Singh's patriotism. He also said that he was opposed to Singh's execution (and, for that matter, capital punishment in general) and proclaimed that he had no power to stop it. On Singh's execution, Gandhi said, "The government certainly had the right to hang these men. However, there are some rights which do credit to those who possess them only if they are enjoyed in name only."[116] Gandhi also once said, on capital punishment, "I cannot in all conscience agree to anyone being sent to the gallows. God alone can take life because He alone gives it."[117]

Gandhi had managed to have 90,000 political prisoners who were not members of his Satyagraha movement released under the Gandhi-Irwin Pact.[107] According to a report in the Indian magazine Frontline, he did plead several times for the commutation of the death sentence of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev, including a personal visit on March 19, 1931, and in a letter to the Viceroy on the day of their execution, pleading fervently for commutation, not knowing that the letter would be too late.[107]

Lord Irwin, the Viceroy, later said:

As I listened to Mr. Gandhi putting the case for commutation before me, I reflected first on what significance it surely was that the apostle of non-violence should so earnestly be pleading the cause of the devotees of a creed so fundamentally opposed to his own, but I should regard it as wholly wrong to allow my judgment to be influenced by purely political considerations. I could not imagine a case in which under the law, penalty had been more directly deserved.[107]

However, Gandhi did appreciate Singh's patriotism and how he had overcome the fear of death, but did not support the violence involved.[118]

Saunders family

On October 28, 2005, a book entitled Some Hidden Facts: Martyrdom of Shaheed Bhagat Singh—Secrets unfurled by an Intelligence Bureau Agent of British-India [sic] by K.S. Kooner and G.S. Sindhra was released. The book asserts that Singh, Rajguru, and Sukhdev were deliberately hanged in such a manner as to leave all three in a semi-conscious state, so that all three could later be taken outside the prison and shot dead by the Saunders family. The book says that this was a prison operation codenamed "Operation Trojan Horse." Scholars are sceptical of the book's claims.[82]

Legacy

Indian independence movement

Singh's death had the effect that he desired and he inspired thousands of youths to assist the remainder of the Indian independence movement. After his hanging, youths in regions around Northern India rioted in protest against the British Raj and Gandhi. [119]

Memorials and Museums

- Statue in the Parliament of India

A bronze, 18-foot statue of Singh has been installed in the Parliament of India, next to the statutes of Indira Gandhi and Subash Chandra Bose.[120]

- National Martyrs Memorial

Singh was cremated at Hussainiwala on banks of Sutlej river. The National Martyrs Memorial Hussainiwala, built in 1968,[121] depicts an irrepressible revolutionary spirit of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev. The memorial is located just one km from the India-Pakistan border on the Indian side and has memorials of Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev. After Partition, the cremation spot fell inside Pakistan but on January 17, 1961, it was transferred to India when India gave 12 villages near the Sulemanki Headworks (Fazilka) to Pakistan. During the 1971 India-Pakistan war, the statues of these martyrs were removed and taken away by Pakistan army which have not been returned.[86][122] This memorial was damaged by the withdrawing Pakistani troops in 1972. The memorial came up once again in 1973 due to the efforts of the then Punjab Chief Minister, Giani Zail Singh.[87] B.K. Dutt was also cremated here on July 19, 1965 and in accordance with his last wishes. Singh's mother, Vidyawati, was also cremated here in accordance with her last wish.[87]

Every year, on the March 23, the Shaheedi Mela is observed at this National Martyrs Memorial at Hussainiwala, in which thousands of people pay their homage.[123] The day is also observed across the state of Punjab.[citation needed]

- Bhagat Singh Museum & Bhagat Singh Memorial

The "Shaheed-e-azam Sardar Bhagat Singh Museum" at Khatkar Kalan, the native village of Singh, came up on his 50th death anniversary, where memorable belongings of Singh, including his half burnt ashes and the blood soaked sand and blood stained newspaper in which the ashes were wrapped are exhibited[124]. A page of the first Lahore Conspiracy Case’s judgement through which martyr Kartar Singh Sarabha was sentenced to death and on which Singh put some notes is also exhibited in the museum. A copy of holy Gita having Singh’s signatures which was handed over to him in Lahore Jail, and his other personal belongings are displayed here.[125][126]

The Bhagat Singh Memorial was built in 2009 in his hometown of Khatkar Kalan at a cost of Rs.168 million.[127]

Modern day

To celebrate the centenary of his birth, a group of intellectuals set up an institution to commemorate Singh and his ideals.[128]

Several popular Bollywood films have been made capturing the life and times of Singh.[15] The first is Shaheed-e-Azad Bhagat Singh (1954), followed by Shaheed Bhagat Singh (1963), starring Shammi Kapoor as Singh.[129] Two years later, Manoj Kumar portrayed Bhagat Singh in an immensely popular and landmark film, Shaheed.[129] Three major films about Singh were released in 2002: Shaheed-E-Azam, 23rd March 1931: Shaheed and The Legend of Bhagat Singh. The Legend of Bhagat Singh is Rajkumar Santoshi's adaptation, in which Ajay Devgan played Singh and Amrita Rao was featured in a brief role. 23rd March 1931: Shaheed was directed by Guddu Dhanoa and starred Bobby Deol as Singh, with Sunny Deol and Aishwarya Rai in supporting roles. Another major film Shaheed-E-Azam, starring Sonu Sood, Maanav Vij, Rajinder Gupta, and Sadhana Singh, and directed by Sukumar Nair, was produced by Iqbal Dhillon under the banner of Surjit Movies.[15]

- Movies on Bhagat Singh

- Shaheed-e-Azad Bhagat Singh (1954)

- Shaheed Bhagat Singh (1963)

- Shaheed (1965)

- Shaheed-E-Azam (2002)

- 23rd March 1931: Shaheed (2002)

- The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002)

- Rang De Basanti (2006)

The 2006 film Rang De Basanti is a film drawing parallels between revolutionaries of Singh's era and modern Indian youth. It covers a lot of Singh's role in the Indian freedom struggle. The movie revolves around a group of college students and how they each play the roles of Singh's friends and family.

The patriotic Urdu and Hindi songs, Sarfaroshi ki Tamanna (translated as "the desire to sacrifice") and Mera Rang De Basanti Chola ("my light-yellow-coloured cloak"; Basanti referring to the light-yellow color of the Mustard flower grown in the Punjab and also one of the two main colours of the Sikh religion as per the Sikh rehat meryada (code of conduct of the Sikh Saint-Soldier)), while created by Ram Prasad Bismil, are largely associated to Singh's martyrdom and have been used in a number of Singh-related films.[15]

In September 2007 the Governor of Punjab province, Khalid Maqbool, announced that a memorial to Singh would be displayed at Lahore Museum. According to the governor: "Singh was the first martyr of the subcontinent and his example was followed by many youth of the time."[130][36] However, the promise remains unfulfilled.[131][132] In 2008, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) and Act Now for Harmony and Democracy (ANHAD), a non-profit organisation, co-produced a 40-minute documentary on Bhagat Singh entitled Inqilab, directed by Gauhar Raza.[133][134]

Criticism

Singh was criticised both by his contemporaries and by people after his death because of his violent and revolutionary stance towards the British and his strong opposition to the pacifist stance taken by the Indian National Congress and particularly Mahatma Gandhi.[135] The methods he used to make his point - shooting Saunders and throwing non-lethal bombs were quite different from Gandhi's non-violent methodology.[135]

Quotations

- "The aim of life is no more to control the mind, but to develop it harmoniously; not to achieve salvation here after, but to make the best use of it here below; and not to realise truth, beauty and good only in contemplation, but also in the actual experience of daily life; social progress depends not upon the ennoblement of the few but on the enrichment of democracy; universal brotherhood can be achieved only when there is an equality of opportunity - of opportunity in the social, political and individual life." — from Bhagat Singh's prison diary, p. 124

- "Any man who stands for progress has to criticize, disbelieve and challenge every item of the old faith. Item by item he has to reason out every nook and corner of the prevailing faith. If after considerable reasoning one is led to believe in any theory or philosophy, his faith is welcomed. His reasoning can be mistaken, wrong, misled and sometimes fallacious. But he is liable to correction because reason is the guiding star of his life. But mere faith and blind faith is dangerous: it dulls the brain, and makes a man reactionary." - Why I am an atheist? (1930)

See also

References

- ^ a b Rana (2005). p. 124.

- ^ a b "Indian History: Indian Freedom Struggle (1857-1947)". NIC.

- ^ a b c d e Singh, Bhagat (October 5–6, 1930). "Why I am an Atheist" (in Punjabi). Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Panikkar, K.N. (October 20, 2007). "Celebrating Bhagat Singh". Frontline. Frontline (magazine). Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Datta, V. N. (March 11, 2007). "Understanding Bhagat Singh". The Tribune. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Dasgupta, Saibal (September 22, 2010). "Bhagat Singh was set to become a Gandhian: Historian". The Times of India. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "He left a rich legacy for the youth". The Tribune. March 19, 2006. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rao, Niraja (1997). "Bhagat Singh and the Revolutionary Movement". Revolutionary Democracy. 3 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Heer, Gurmit (Fall 2007). "Bhagat Singh" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 14 (2): 297–326. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Habib (2007). p. 145.

- ^ Nayar (2000). p. 93.

- ^ a b Reeta Sharma (March 21, 2001). "What if Bhagat Singh had lived". The Tribune. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "RSS wants Bharat Ratna for Bhagat Singh". Rediff. January 21, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "RSS mouthpiece snubs Bharat Ratna demand for Vajpayee". Indian Express. January 22, 2008. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "A non-stop show..." The Hindu. Monday, Jun 03, 2002. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Singh, Roopinder (March 23, 2011). "Bhagat Singh: The Making of the Revolutionary". The Tribune. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

Bhagat Singh was a well-read, articulate young man who significantly impacted Indian history and left behind a legacy that even 80 years after his martyrdom is still very much a part of our cultural ethos

- ^ "Mark of the Martyr in Pakistan". The Tribune. September 23, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ Rahlan (2002). p. 349.

- ^ "Chapter XIX". Gazetteer Nawanshahr. Department of Revenue, Rehabilitation and Disaster Management, Government of Punjab. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

The news of the release of his uncle Ajit Singh from Mandlay Jail and his father Kishan Singh from Lahore Jail coincided with Singh's birth. His grandmother used to call him 'Bhaganwala'.

- ^ "Shaheed-e-Azam Bhagat Singh". Shaheed Bhagat Singh Evening College, Government of Delhi, India. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Sanyal, Jitendra N. (2006). Bhagat Singh: Making of a Revolutionary: Contemporaries' Portrayals. Gurgaon, Haryana, India: Hope India Publications. p. 25. ISBN 81-7871-059-5.

- ^ Sindhu, Veerendra (2009). Yugdrashta Bhagat Singh (in Hindi). Delhi, India: Rajpal and Sons. p. 121. ISBN 978-8170282051.

- ^ Sanyal, Yadav, Singh et al. (2006). pp. 20–21.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale H. (2000). Students' Britannica India. Vol. 1. New Delhi, India: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. (India). p. 188. ISBN 0-85229-760-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|authorlink=value (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nayar (2000). pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b Ranjit Singh; Kripa Shankar (January 1, 2008). Sikh Achievers. Hemkunt Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-81-7010-365-3. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Sanyal, Yadav, Singh et al. (2006). p. 23.

- ^ Singh, Hooja (2007). p. 14.

- ^ a b "Bhagat Singh: A Perennial Saga Of Inspiration". Pragoti. September 27, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Datta, Vishwa Nath (2008). Gandhi and Bhagat Singh. New Delhi: Rupa & Co. p. 126.

- ^ Singh, Hooja (2007). p. 16.

- ^ Desai (ed.) (2007).

- ^ "Sardar Bhagat Singh (1907-1931)". Research Reference and Training Division, Ministry of Information & Bradcasting, Government of India. Government of India. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Om Gupta (April 1, 2006). Encyclopaedia of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Gyan Publishing House. p. 323. ISBN 978-81-8205-389-2. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ a b Raghunath Rai (2006). History For Class 12: Cbse. India: VK Publications. p. 187. ISBN 978-8187139690.

- ^ a b Ali, Mahir (September 26, 2007). "Requiem for a freedom fighter". Dawn. Dawn (newspaper). Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Singh, Hazara (2007). Freedom Struggle against Imperialism (PDF). Ludhiana, India: Hazara Singh, www.hazarasingh.com. p. 86. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000), p. 39

- ^ Parkash, Chander (March 23, 2011). "National Monument Status Eludes Building". The Tribune. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Rana (2005). p. 39.

- ^ Rana, Bhawan Singh (January 1, 2005). Chandra Shekhar Azad (An Immortal Revolutionary of India). Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-81-288-0816-6. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000). p. 42.

- ^ S.R. Bakshi (1988). Revolutionaries and the British Raj. Atlantic Publishers & Distri. p. 61. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ a b "Defence of India Act". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ralhan (1998). pp. 438–439.

- ^ "INDIA: Jam Tin Gesture". Time. April 22, 1929. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Bhagat Singh Remembered". Daily Times Pakistan. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Leaflet thrown in the Central Assembly Hall, New Delhi at the time of the throwing voice bombs". Letter, Writtings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b "Full Text of Statement of S. Bhagat Singh and B.K. Dutt in the Assembly Bomb Case". Letter, Writtings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c d e "The Trial of Bhagat Singh". India Law Journal. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Regarding the LCC". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Co-Patriots. . Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Nayar (2000), p.77

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.118

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.81

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.83

- ^ Nayar (2000), pages 84-89

- ^ Singh, Bhagat. "Hunger-strikers' demands". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher=|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nayar (2000), p. 85

- ^ Dutt, Nirupama (July 24, 2005). "The Tribune stood up for Bhagat Singh". The Tribune. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "When Jinnah defended Bhagat Singh". The Hindu. August 8, 2005. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Ghosh, Ajoy (October 6, 2007). "Bhagat Singh as I knew Him". Mainstream. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.88

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.89

- ^ Nayar (2000), p. 89

- ^ Nayar (2000), p. 91

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.92

- ^ Lal, Chaman (August 15, 2011). "Letters written by Bhagat Singh to British authorities". The Hindu. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.96

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.100

- ^ Sanyal, Yadav, Singh et al. (2006), p. 129

- ^ Sanyal, Yadav, Singh et al. (2006), p. 130

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.103

- ^ Nayar (2000), p.117

- ^ "Ordinance No. III of 1930". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

particularly sections 1, 3, 4, 9, 10 & 11

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Nayar (2000), p.119

- ^ Rana(2005), pages 95-100

- ^ Rana(2005), p. 98

- ^ Rana(2005), p. 103

- ^ Rana(2005), p. 98

- ^ "Jail Note Book of Shahid Bhagat Singh". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Gems Collected by Shaheed Bhagat Singh in Jail". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana]. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b Ahuja, Chaman (December 11, 2005). "Was Bhagat Singh shot dead?". The Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000). pp. 132–134.

- ^ "Excerpts:'Operation Trojan Horse'". The Tribune. December 11, 2005. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Kaushik, R. K. (October 09, 2011). "Bhagat singh, the final hours". Hindustan Times. Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b "National Martyrs Memorial, Hussainiwala". District Administration, Firozepur, Punjab. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Shaheedon ki dharti". The Tribune. 03 July 1999. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kaushik, R. K. (October 09, 2011). "Bhagat singh, the final hours". Hindustan Times. Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Supreme Court of India - Photographs of the exhibition on the "Trial of Bhagat Singh"". Supreme Court of India. Supreme Court of India. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Sedhuraman, R (August 12, 2011). "Bhagat Singh executed illegally: Researcher". The Tribune. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Lal, Chaman (August 15, 2011). "Rare documents on Bhagat Singh's trial and life in jail". The Hindu. The Hindu. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Indian executions stun the congress". The New York Times. March 25, 1931. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "50 die in India riot; Gandhi assaulted as party gathers". The New York Times. March 26, 1931. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Indian Hartals of ten invoked; Strikes of Mourning Are Called as Weapons in Public Campaigns". The New York Times. March 27, 1931. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "INDIA: Naked to Buckingham Palace". Time. April 06, 1931. p. 3. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Sinha, Ashish (December 21, 2007). "Bhagat Singh no terrorist: Govt". The Times of India. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Jason Adams. "Asian Anarchism: China, Korea, Japan & India". Raforum.info. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "Bhagat Singh an early Marxist, says Panikkar". The Hindu. October 14, 2007. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "Remembering Terence MacSwiney". Creative Resistance. Design and People. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ "Blood Sprinkled on the Day of Holi Babbar Akalis on the Crucifix*". Letter, Writtings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Bhagat Singh. "To Young Political Workers". Marxists.org. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Chinmohan Sehanavis. "Impact of Lenin on Bhagat Singh's Life". Mainstream Weekly. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ Nayar (2000). p. 26.

- ^ Niralamba Swami was the name taken by Bengali revolutionary Jatindra Nath Banerjee, an early member of the Anushilan Samiti, after he gave up his political activism and became an ascetic.

- ^ Nayar (2000). p. 27.

- ^ "Leaflet thrown in the Central Assembly Hall, New Delhi at the time of the throwing bombs". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b c d Vaidya, Paresh R. (April 14–27, 2001). "Of means and ends". Frontline. 18 (Issue 08). Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|issue=has extra text (help) - ^ Singh, Randhir (1978). Jail Chithian (PDF) (in Punjabi). Ludhiana: B.S.Randhir Singh Publishing House. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Singh, Bhagat (1930). "Why I am an Atheist". Letters, Writings and Statements of Shaheed Bhagat Singh and his Copatriots. Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Trilochan Singh (1971). [page number needed]."Bhagat Singh: I'm really ashamed and am prepared to tell your frankly that I removed my hair and beard under pressing circumstances. It was for the service of the country that my companions compelled me to give up the Sikh appearance... Randhir Singh: I was glad to see Bhagat Singh repentant and humble in his present attitude towards religious symbols"

- ^ a b Pinney (2004). [page number needed]."Although born into a Jat Sikh family and returning to the turban just prior to his execution, under the influence of Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh, his popular visual incarnation has nearly always been a mimic of the English sahab".

- ^ a b Sangat Singh (1995). [page needed]. "Bhagat Singh's last wish, that he be administered amrit, Sikh baptism, by a group of five including Bhai Randhir Singh was not fulfilled by the British".

- ^ "The Idea of Bhagat Singh". Iosworld.org. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c Datta, V. N. (July 27, 2008). "Mahatma and the Martyr". The Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Historical Analysis: Of means and ends". Frontline. Frontline. April 14 - 27, 2001. Retrieved November 01, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Ahmedabad, Navjivan. vol. 45, pp. 359-61 (Gujarati)

- ^ Sachar, Rajindar (May 17, 2008). "Death to the death penalty". Tehelka. Tehelka. Retrieved November 01, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Mahatma Gandhi on the Martyrdom of Bhagat Singh". Mahatma Gandhi Album. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

Excerpts from Gandhi's article in Young India dated March 29, 1931

- ^ Singh, Pritam (September 24, 2008). "Book review: Why the Story of Bhagat Singh Remains on the Margins?". Retrieved October 29, 2011.

review of S Irfan Habib, To Make the Deaf Hear: Ideology and Programme of Bhagat Singh and His Comrades (New Delhi: Three Essays Collective, 2007), xviii+231pp., ISBN 81-88789-56-9 (hardbound) and, ISBN 81-88789-61-5 (paperback).

- ^ Tandon, Aditi (August 8, 2008). "Prez to unveil martyr's 'turbaned' statue". The Tribune. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Bains, K. S. (September 23, 2007). "Making of a memorial". The Tribune. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Retreat ceremony at Hussainiwala (Indo-Pak Border)". District Administration Ferozepur, Government of Punjab. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Dress and Ornaments". Gazetteer of India, Punjab, Firozpur (First Edition). Department of Revenue, Rehabilitation and Disaster Management, Government of Punjab. 1983. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Dhaliwal, Sarbjit (March 23, 2011). "Policemen make a beeline for museum". The Tribune. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Chapter XIV (f)". Gazetteer Jalandhar. Department of Revenue, Rehabilitation and Disaster Management, Government of Punjab. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Chapter XV". Gazetteer Nawanshahr. Department of Revenue, Rehabilitation and Disaster Management, Government of Punjab. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Bhagat Singh memorial in native village gets go ahead". Indo-Asian News Service. January 30, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "In memory of Bhagat Singh". The Tribune. January 1, 2007. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Vijayakar, Rajiv (March 19, 2010). "Pictures of Patriotism". Screen. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ "Memorial will be built to Bhagat Singh, says governor". Daily Times (Pakistan). September 2, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Jail where Bhagat Singh held in ruins; memorial promise unkept". Deccan Herald. October 16, 2010. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Singh, Prabhjit (March 23, 2011). "A play, candle lights in Lahore for Shaheed's memorial". Hindustan Times. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "New film tells 'real' Bhagat Singh story". The Hindustan Times. Hindustan Times. July 13, 2008. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ "Documentary on Bhagat Singh". The Hindu. July 8, 2008. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ a b Tandon, Aditi (May 13, 2007). "Mark of a Martyr". The Tribune. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

Bibliography

- Desai, Datta, ed. (March 28–29, 2007), "Revisiting Bhagat Singh: Ideology and Politics", National Seminar on 'Bhagat Singh and Beyond: Rethinking Radicalism in Indian Society, Culture and Politics' organised by the Dept. of Civics and Politics, University of Mumbai, Mumbai: Shahid Bhagat Singh Research Committee, Ludhiana, retrieved October 11, 2011

{{citation}}: External link in|publisher= - Habib, S. Irfan; Singh, Bhagat (2007). To make the deaf hear: ideology and programme of Bhagat Singh and his comrades. Three Essays Collective. ISBN 978-81-88789-56-6.

- Nayar, Kuldip (2000). The martyr: Bhagat Singh experiments in revolution. Har-Anand Publications. p. 93. ISBN 978-81-241-0700-3.

- Pinney, Christopher (2004). "Photos Of The Gods": The Printed Image And Political Struggle In India. London, UK: Reaktion Books. p. 239. ISBN 978-1861891846.

- Ralhan, Om Prakash (1998). Post-independence India. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-7488-865-5.

- Ralhan, Om Prakash, ed. (2002). Encyclopaedia of Political Parties. Vol. 26. New Delhi, India: Anmol Publications. ISBN 81-7488-313-4.

- Rana, Bhawan Singh (2005). Bhagat Singh. Diamond Pocket Books (P) Ltd. ISBN 978-81-288-0827-2.

- Sanyal, Jatinder Nath; Yadav, Kripal Chandra; Singh, Bhagat; Singh, Babar, The Bhagat Singh Foundation (2006). Bhagat Singh: a biography. Pinnacle Technology. ISBN 978-81-7871-059-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Singh, Bhagat; Hooja, Bhupendra (2007). The Jail Notebook and Other Writings. LeftWord Books. ISBN 978-81-87496-72-4.

- Singh, Sangat (1995). The Sikhs in History. New York: S. Singh. p. 552. ISBN 978-0964755505.

- Singh, Randhir; Singh, Trilochan (1995). Autobiography of Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh (Translated by Dr. Trilochan Singh) (3 ed.). Punjab, India: Bhai Sahib Randhir Singh Trust. ASIN B000O9CWL2.

External links

- Shaheed Bhagat Singh in Jail - A different perspective.

- Bhagat Singh - comic

- Freedom fighter Bhagat Singh

- Bhagat Singh at freeindia.org

- Bhagat Singh Biography and Contains letters written by Bhagat Singh

- Martyrdom of Sardar Bhagat Singh by Jyotsna Kamat

- His Violence Wasn't Just About Killing, Outlook magazine.

- Use mdy dates from August 2010

- Punjabi people

- Revolutionary movement for Indian independence

- Indian revolutionaries

- Indian communists

- Indian atheists

- Indian anarchists

- Indian Sikhs

- Executed revolutionaries

- People executed by hanging

- 20th-century executions by the United Kingdom

- Executed Indian people

- People executed by British India

- People executed for murdering police officers

- 1907 births

- 1931 deaths