Origin of the Romanians: Difference between revisions

Being aggressive (as well as an admirer of Borsoka) doesn't automatically make you right. |

→Theories on the Romanians' ethnogenesis: re-adding relevant RS content which was removed without reason (as in vandalism) by Borsoka |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Theories on the Romanians' ethnogenesis== |

==Theories on the Romanians' ethnogenesis== |

||

{{Quote|''The scholarly and, often, polemical debate about the continued presence of a Daco-Roman population north of the Danube, particularly on the territory of the old Roman province'' [of [[Dacia Traiana]]] ''(much of Transylvania, the Banat, and Oltenia) after Aurelian’s withdrawal has been clouded by a paucity of firsthand sources and, in modern times, by national passions. The controversy has been wide-ranging and has lasted down to the post-Communist era, though it has assumed an attenuated form as membership in the European Union has softened territorial rivalries between Romania and Hungary.''|Keith Hitchins (2014) {{sfn|Hitchins|2014|p=17}}}} |

|||

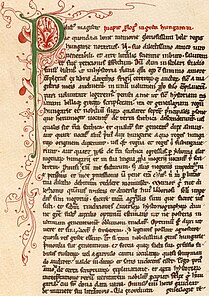

[[File:Map Length of Roman Rule Neo Latin Languages.jpg|thumb|right|Length of Roman rule and distribution of modern [[Romance languages]]. Romanian is the only Romance language which is spoken primarily in territories which were never or only for about 170 years under Roman rule.]] |

[[File:Map Length of Roman Rule Neo Latin Languages.jpg|thumb|right|Length of Roman rule and distribution of modern [[Romance languages]]. Romanian is the only Romance language which is spoken primarily in territories which were never or only for about 170 years under Roman rule.]] |

||

Revision as of 14:24, 27 November 2018

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

Several well-supported theories address the issue of the origin of the Romanians[citation needed]. The Romanian language descends from the Vulgar Latin dialects spoken in the Roman provinces north of the "Jireček Line" (a proposed notional line separating the predominantly Latin-speaking territories from the Greek-speaking lands in Southeastern Europe) in Late Antiquity. The theory of Daco-Roman continuity argues that the Romanians are mainly descended from the Daco-Romans, a people developing through the cohabitation of the native Dacians and the Roman colonists in the province of Dacia Traiana (primarily in present-day Romania) north of the river Danube. The competing immigrationist theory states that the Romanians' ethnogenesis commenced in the provinces south of the river with Romanized local populations (known as Vlachs in the Middle Ages) spreading through mountain refuges, both south to Greece and north through the Carpathian Mountains. According to the "admigration theory", migrations from the Balkan Peninsula to the lands north of the Danube contributed to the survival of a Romance-speaking population in those territories.

Historic background

Three major ethnic groups – the Dacians, Illyrians and Thracians – inhabited the northern regions of Southeastern Europe in Antiquity.[1] Modern knowledge of their languages is based on limited evidence (primarily on proper names), making all scholarly theories proposing a strong relationship between the three languages or between Thracian and Dacian speculative.[2] The Illyrians were the first to be conquered by the Romans, who organized their territory into the province of Illyricum around 60 BC.[3] In the lands inhabited by Thracians, the Romans set up the province of Moesia in 6 AD, and Thracia forty years later.[4] Present-day Dobruja was attached to Moesia in 46.[5] The Romans annihilated the Dacian kingdom to the north of the Lower Danube under Emperor Trajan in 106.[6] Its western territories were organized into the province of Dacia (or "Dacia Traiana"), but Maramureș and further regions inhabited by the Costoboci, Bastarnae and other tribes remained free of Roman rule.[7] The Romans officially abandoned Dacia under Emperor Aurelian (r. 270–275), who organized a new province bearing the same name ("Dacia Aureliana") south of the Lower Danube.[8] Although Roman forts were erected north of the Danube in the 320s,[9] the river became the boundary between the empire and the Goths in the 360s.[10]

Meanwhile, from 313 under the Edict of Milan, the Roman Empire began to transform itself into a Christian state.[11] Roman emperors supported Christian missionaries in the lands dominated by the Goths from the 340s.[12] The Huns destroyed all these territories between 376 and 406, but their empire also collapsed in 453.[13] Thereafter the Gepids dominated Banat, Crișana, and Transylvania.[14] The Bulgars, Antes, Sclavenes and other tribes made frequent raids across the Lower Danube against the Balkans in the 6th century.[15] The Roman Empire revived under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565),[16] but the Avars, who had subjugated the Gepids,[17] invaded the Balkans from the 580s.[18] In 30 years all Roman troops were withdrawn from the peninsula, where only Dyrrhachium, Thessaloniki and a few other towns remained under Roman rule.[19]

The next arrivals, the Bulgars, established their own state on the Lower Danube in 681.[20] Their territorial expansion accelerated after the collapse of the Avar Khaganate in the 790s.[21] The ruler of the First Bulgarian Empire, Boris I (r. 852–889) converted to Christianity in 864.[22] A synod of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church promoted a liturgy in Old Church Slavonic in 893.[23] Bulgaria was invaded by the Magyars (or Hungarians) in 894,[24] but a joint counter-attack by the Bulgars and the Pechenegs – a nomadic Turkic people – forced the Magyars to find a new homeland in the Carpathian Basin.[25] Historians still debate whether they encountered a Romanian population in the territory.[26][27] The Byzantines occupied the greater part of Bulgaria under Emperor John I Tzimiskes (r. 969–976).[28] The Bulgars regained their independence during the reign of Samuel (r. 997–1014),[29] but Emperor Basil II of Byzantium conquered their country around 1018.[30]

The first bishop consecrated for the Hungarians was a Greek from Constantinople,[31] but their supreme ruler, Stephen, was baptized according to the Western rite.[32] Crowned the first king of Hungary in 1000 or 1001, he expanded his rule over new territories, including Banat.[33] [34][35][36] Pecheneg groups, pushed by the Ouzes – a coalition of Turkic nomads – sought asylum in the Byzantine Empire in the 1040s.[37] After the Ouzes there followed the Cumans – also a Turkic confederation – who took control of the Pontic steppes in the 1070s.[38][39] Thereafter, specific groups, including the Hungarian-speaking Székelys and the Pechenegs, defended the frontiers of the Kingdom of Hungary against them.[40] The arrival of mostly German-speaking colonists in the 1150s also reinforced the Hungarian monarch's rule in the region.[41][42]

The Byzantine authorities introduced new taxes, provoking an uprising in the Balkan Mountains in 1185.[43] The local Bulgarians and Vlachs achieved their independence and established the Second Bulgarian Empire in coalition with the Cumans.[44] A chieftain of the western Cuman tribes accepted Hungarian supremacy in 1227.[45] The Hungarian expansion towards the Pontic steppes was halted by the large Mongol campaign against Eastern and Central Europe in 1241.[46] Although the Mongols withdrew in a year, their invasion caused destruction throughout the region.[47]

The unification of small polities ruled by local Romanian leaders in Oltenia and Muntenia[47] led to the establishment of a new principality, Wallachia.[48] It achieved independence under Basarab the Founder, who defeated a Hungarian army in the battle of Posada in 1330.[48] A second principality, Moldavia, became independent in the 1360s under Bogdan I, a Romanian nobleman from Maramureș.[49]

Theories on the Romanians' ethnogenesis

The scholarly and, often, polemical debate about the continued presence of a Daco-Roman population north of the Danube, particularly on the territory of the old Roman province [of Dacia Traiana] (much of Transylvania, the Banat, and Oltenia) after Aurelian’s withdrawal has been clouded by a paucity of firsthand sources and, in modern times, by national passions. The controversy has been wide-ranging and has lasted down to the post-Communist era, though it has assumed an attenuated form as membership in the European Union has softened territorial rivalries between Romania and Hungary.

— Keith Hitchins (2014) [50]

One of the first scholars who systematically studied the Romance languages, Friedrich Christian Diez, described Romanian as a semi-Romance language in the 1830s.[51] In 2009, Kim Schulte likewise argued that "Romanian is a language with a hybrid vocabulary".[52] The proportion of loanwords in Romanian is indeed higher than in other Romance languages.[53] Its certain structural features—such as the construction of the future tense—also distinguish Romanian from other Romance languages.[53] The same peculiarities connect it to Albanian, Bulgarian and other tongues spoken in the Balkan Peninsula.[54] Nevertheless, as linguist Graham Mallinson emphasizes, Romanian "retains enough of its Latin heritage at all linguistic levels to qualify for membership of the Romance family in its own right", even without taking into account the "re-Romancing tendency" during its recent history.[55] The core vocabulary is to a large degree Latin, including the most frequently used 2500 words.[56][57] Around one-fifth of the entries of the 1958 edition of the Dictionary of the Modern Romanian have directly been inherited from Latin.[58] More than 75% of the words in the semantic fields of sense perception, quantity, kinship and spatial relations are of Latin origin, but the basic lexicons of religion and of agriculture have also been preserved.[59][60]

Romanians, known by the exonym Vlachs in the Middle Ages,[61] speak a language descended from the Vulgar Latin that was once spoken in south-eastern Europe.[62][63] Inscriptions from the Roman period prove that a line, known as the "Jireček Line", can be drawn through the Balkan Peninsula, which separated the Latin-speaking northern provinces, including Dacia, Moesia and Pannonia from the southern regions where Greek remained the predominant language.[64] Eastern Romance now has four variants,[65] which are former dialects of a Proto-Romanian language.[66][67] Daco-Romanian, the official language of Romania, is the most widespread of the four variants.[66] Speakers of the Aromanian language live in scattered communities in Albania, Bulgaria, Greece and Macedonia.[66] Another two, by now nearly extinct variants, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian, are spoken in some villages in Macedonia and Greece, and in Croatia, respectively.[66] Aromanian and Megleno-Romanian are spoken in the central and southern regions of the Balkans, indicating that they migrated to these territories in the Middle Ages.[68][69] Some variants of the Eastern Romance languages retained more elements of their Latin heritage than others.[note 1][70][71]

The territories south of the Danube were subject to the Romanization process for about 800 years, while Dacia province to the north of the river was only for 165 years under Roman rule, which caused "a certain disaccord between the effective process of Roman expansion and Romanization and the present ethnic configuration of Southeastern Europe", according to Lucian Boia.[72] Political and ideological considerations, including the dispute between Hungary and Romania over Transylvania, have also colored these scholarly discussions.[73][50] Accordingly, theories on the Romanian Urheimat or "homeland" can be divided into two or more groups, including the theory of Daco-Roman continuity of the continuous presence of the Romanians' ancestors in the lands north of the Lower Danube and the opposite immigrationist theory.[62][63] Independently of the theories, a number of scholars propose that Romanian developed from the tongue of a bilingual population, because bilingualism is the most probable explanation for its peculiarities.[74][75][76][77]

Historiography: origin of the theories

Byzantine authors were the first to write of the Romanians (or Vlachs).[78] The 11th-century scholar Kekaumenos wrote of a Vlach homeland situated "near the Danube and [...] the Sava, where the Serbians lived more recently".[79][80] He associates the Vlachs with the Dacians and the Bessi and with the Dacian king Decebal.[81] Accordingly, historians have located this homeland in several places, including Pannonia Inferior (Bogdan Petriceicu Hașdeu) and "Dacia Aureliana" (Gottfried Schramm).[82][83] The 12th-century scholar John Kinnamos[84] wrote that the Vlachs "are said to be formerly colonists from the people of Italy".[85][86][87] William of Rubruck wrote that the Vlachs of Bulgaria descended from the Ulac people,[88] who lived beyond Bashkiria.[89] The late 13th-century Hungarian chronicler Simon of Kéza states that the Vlachs used to be the Romans' "shepherds and husbandmen" who "elected to remain behind in Pannonia"[90] when the Huns arrived.[91] An unknown author's Description of Eastern Europe from 1308 likewise states that the Balkan Vlachs "were once the shepherds of the Romans" who "had over them ten powerful kings in the entire Messia and Pannonia".[92][93]

Poggio Bracciolini, an Italian scholar wrote around 1450 that the Romanians' ancestors had been Roman colonists settled by Emperor Trajan.[94] This view was repeated by Aeneas Sylvius Piccolomini, who stated in his work De Europa (1458) that the Vlachs were a genus Italicum ("an Italian race")[95] and were named after one Pomponius Flaccus, a commander sent against the Dacians.[96] Piccolomini's version of the Vlachs' origin was repeated by many scholars in the subsequent century.[97] Flavio Biondo noted that "the Dacians or Wallachs claim to have Roman origins"; Pietro Ranzano wrote that the Vlachs declared themselves "descendants of Italians"; the Transylvanian Saxon Johannes Lebelius mentioned that Trajan "led the Vlachi along with Italian people into the kingdom, spread them all around the Dacian kingdom" and "these people after so many severe fights which they have survived, remained in Dacia, and are now farmers of the land"; the Hungarian Jesuit Stephan Szántó stated that the Wallachians were "the offspring of an ancient colony of the Romans that used to be once in Transylvania" and "true Italians" could understand their language.[98][99] On the other hand, Laonikos Chalkokondyles—a late-15th-century Byzantine scholar—stated that he never heard anyone "explain clearly where" the Romanians "came from to inhabit" their lands.[100] Chalkokondyles also wrote that the Romanians were said to have come "from many places and settled that area".[101] The 17th-century Johannes Lucius expressed his concerns about the survival of Romans in a territory exposed to invasions for a millennium.[100]

A legend on the origin of the Moldavians, preserved in the Moldo-Russian Chronicle from around 1505,[102][103] narrates that one "King Vladislav of Hungary" invited their ancestors to his kingdom and settled them "in Maramureş between the Moreş and Tisa at a place called Crij".[104] Grigore Ureche's Chronicle of Moldavia of 1647[105] is the first Romanian historical work stating that the Romanians "all come from Rîm" (Rome).[106][107][108] In 30 years Miron Costin explicitly connected the Romanians' ethnogenesis to the conquest of "Dacia Traiana".[109] Constantin Cantacuzino stated in 1716 that the native Dacians also had a role in the formation of the Romanian people.[107][110] Petru Maior and other historians of the "Transylvanian School" flatly denied any interbreeding between the natives and the conquerors, claiming that the autochthonous Dacian population which was not eradicated by the Romans fled the territory.[111] The Daco-Roman mixing became widely accepted in the Romanian historiography around 1800. This view is advocated by the Greek-origin historians Dimitrie Philippide (in his 1816 work History of Romania) and Dionisie Fotino, who wrote History of Dacia (1818).[112][113] The idea was accepted and taught in the Habsburg Monarchy, including Hungary until the 1870s,[114] although the Austrian Franz Joseph Sulzer had by the 1780s rejected any form of continuity north of the Danube, and instead proposed a 13th-century migration from the Balkans.[115]

The development of the theories was closely connected to political debates in the 18th century.[116][117][118] Sulzer's theory of the Romanians' migration was apparently connected to his plans on the annexation of Wallachia and Moldavia by the Habsburg Monarchy, and the settlement of German colonists in both principalities.[119] The three political "nations" of the Principality of Transylvania (the Hungarians, Saxons and Székelys) enjoyed special privileges, while local legislation emphasized that the Romanians had been "admitted into the country for the public good" and they were only "tolerated for the benefit of the country".[117][120] When suggesting that the Romanians of Transylvania were the direct descendants of the Roman colonists in Emperor Trajan's Dacia, the historians of the "Transylvanian School" also demanded that the Romanians were to be regarded as the oldest residents of the country.[117][121] The Supplex Libellus Valachorum – a petition completed by the representatives of the local Romanians in 1791 – explicitly demanded that the Romanians should be granted the same legal status that the three privileged "nations" had enjoyed because the Romanians were of Roman stock.[122][123]

Theory of Daco-Roman continuity

Scholars supporting the continuity theory argue that the Romanians descended primarily from the inhabitants of "Dacia Traiana", the province encompassing three or four regions of present-day Romania to the north of the Lower Danube from 106.[124] In these scholars' view, the close contacts between the autochthonous Dacians and the Roman colonists led to the formation of the Romanian people because masses of provincials stayed behind after the Roman Empire abandoned the province in the early 270s.[125][126][127] Thereafter the process of Romanization expanded to the neighboring regions due to the free movement of people across the former imperial borders.[11][128] The spread of Christianity contributed to the process, since Latin was the language of liturgy among the Daco-Romans.[11] The Romans held bridgeheads norths of the Lower Danube, keeping Dacia within their sphere of influence uninterruptedly until 376.[129][130] The north-Danubian regions remained the main "center of Romanization" after the Slavs started assimilating the Latin-speaking population in the lands south of the river, or forcing them to move even further south in the 7th century.[131][132][133] Although for a millennium migratory peoples invaded the territory, a sedentary Christian Romance-speaking population survived, primarily in the densely forested areas, separated from the "heretic" or pagan invaders.[134][135] [136] Only the "semisedentarian" Slavs exerted some influence on the Romanians' ancestors, especially after they adopted Orthodox Christianity in the 9th century.[132][137] They played the role in the Romanians' ethnogenesis that the Germanic peoples had played in the formation of other Romance peoples.[132][137][74]

Historians who accept the continuity theory emphasize that the Romanians "form the numerically largest people" in southeastern Europe.[130][138][139][140] Romanian ethnographers point at the "striking similarities" between the traditional Romanian folk dress and the Dacian dress depicted on Trajan's Column as a clear evidence for the connection between the ancient Dacians and modern Romanians.[141][142] They also highlight the importance of the massive and organized colonization of Dacia Traiana.[143][144][145] One of them, Coriolan H. Opreanu underlines that "nowhere else has anyone defied reason by stating that a [Romance] people, twice as numerous as any of its neighbours..., is only accidentally inhabiting the territory of a former Roman province, once home to a numerous and strongly Romanized population".[139] With the colonists coming from many provinces and living side by side with the natives, Latin must have emerged as their common language.[143][144][146] The Dacians willingly adopted the conquerors' superior culture and they spoke Latin as native tongue after two or three generations.[147][148] Estimating the provincials' number at 500,000-1,000,000 in the 270s, supporters of the continuity theory rule out the possibility that masses of Latin-speaking commoners abandoned the province when the Roman troops and officials left it.[127][149][50] Historian Ioan-Aurel Pop concludes that the relocation of hundreds of thousands of people across the Lower Danube in a short period was impossible, especially because the commoners were unwilling to "move to foreign places, where they had nothing of their own and where the lands were already occupied."[149] Romanian historians also argue that Roman sources failed to mention that the whole population was moved from Dacia Traiana.[50]

Most Romanian scholars accepting the continuity theory regard the archaeological evidence for the uninterrupted presence of a Romanized population in the lands now forming Romania undeniable.[149][150][151][152] Especially, artefacts bearing Christian symbolism, hoards of bronze Roman coins and Roman-style pottery are listed among the archaeological finds verifying the theory.[130][153] The same scholars emphasize that the Romanians directly inherited the basic Christian terminology from Latin, which also substantiates the connection between Christian objects and the Romanians' ancestors.[154][155] Other scholars who support the same theory underline that the connection between certain artefacts or archaeological assemblages and ethnic groups is uncertain.[152][156] Instead of archaeological evidence, Alexandru Madgearu highlights the importance of the linguistic traces of continuity, referring to the Romanian river names in the Apuseni Mountains and the preservation of archaic Latin lexical elements in the local dialect.[157] The survival of the names of the largest rivers from Antiquity is often cited as an evidence for the continuity theory,[158][159] although some linguists who support it notes that a Slavic-speaking population transmitted them to modern Romanians.[160] Some words directly inherited from Latin are also said to prove the countinuous presence of the Romanians' ancestors north of the Danube, because they refer to things closely connected to these regions.[161] For instance, linguist Marius Sala argues that the Latin words for oil, gold and bison could only be preserved in the lands to the north of the river.[161]

Written sources did not mention the Romanians, either those who lived north of the Lower Danube or those living to the south of the river, for centuries.[162] Scholars supporting the continuity theory notes that the silence of sources does not contradict it, because early medieval authors named the foreign lands and their inhabitants after the ruling peoples.[162] Hence, they mentioned Gothia, Hunia, Gepidia, Avaria, Patzinakia and Cumania, and wrote of Goths, Huns, Gepids, Avars, Pechenegs and Cumans, without revealing the multi-ethnic character of these realms.[162] References to the Volokhi in the Russian Primary Chronicle, and to the Blakumen in Scandinavian sources are often listed as the first records of north-Danubian Romanians.[163][164][165] The Gesta Hungarorum—the oldest extant Hungarian chronicle—mentioned the Vlachs and the "shepherds of the Romans" (along with the Bulgarians, Slavs, Greeks and other peoples) among the inhabitants of the Carpathian Basin at the time of the arrival of the Magyars (or Hungarians) in the late 9th century; Simon of Kéza's later Hungarian chronicle identified the Vlachs as the "Romans shepherds and husbandman" who remained in Pannonia.[163][166] [167] Pop concludes that the two chronicles "assert the Roman origin of Romanians... by presenting them as the Romans' descendants" who stayed in the former Roman provinces.[168]

Immigrationist theory

Scholars who support the immigrationist theory propose that the Romanians descended from the Romanized inhabitants of the provinces to the south of the Danube.[169][170][171] Following the collapse of the empire's frontiers around 620, some of this population moved south to regions where Latin had not been widely spoken.[172] Others took refuge in the Balkan Mountains where they adopted an itinerant form of sheep- and goat-breeding, giving rise to the modern Vlach shepherds.[169] Their mobile lifestyle contributed to their spread in the mountainous zones.[169][173] The start of their northward migration cannot exactly be dated, but they did not settle in the lands north to the Lower Danube before the end of the 10th century and they crossed the Carpathians after the mid-12th century.[174]

Immigrationist scholars emphasize that all other Romance languages developed in regions which had been under Roman rule for more than 500 years and nothing suggests that Romanian was an exception.[175][176] Even in Britain, where the Roman rule lasted for 365 years (more than twice as long as in Dacia Traiana) the pre-Roman languages survived.[175] Proponents of the theory have not developed a consensual view about the Dacians' fate after the Roman conquest, but they agree that the presence of a non-Romanized rural population (either the remnants of the local Dacians, or immigrant tribesmen) in Dacia Traiana is well-documented.[177][178] The same scholars find it hard to believe that the Romanized elements preferred to stay behind when the Roman authorities announced the withdrawal of the troops from the province and offered the civilians to also move to the Balkans.[175][179] Furthermore, the Romans had started fleeing from Dacia Traiana decades before it was abandoned.[180]

Almost no place name has been preserved in the former province (while more than twenty settlements still bear a name of Roman origin in England).[175] The present forms of the few river names inherited from Antiquity show that non-Latin-speaking populations—Dacians and Slavs—mediated them to the modern inhabitants of the region.[181] Both literary sources and archaeological finds confirm this conjecture: the presence of Carpians, Vandals, Taifals, Goths, Gepids, Huns, Slavs, Avars, Bulgarians and Hungarians in the former Roman province in the early Middle Ages is well documented.[182] Sporadic references to few Latin-speaking individuals—merchants and prisoners of war—among the Huns and Gepids in the 5th century does not contradict this picture.[183] Since Eastern Germanic peoples inhabited the lands to the north of the Lower Danube for more than 300 years, the lack of loanwords borrowed from them also indicates that the Romanians' homeland was located in other regions.[175][184] Likewise, no early borrowings from Eastern or Western Slavic languages can be proven, although the Romanians' ancestors should have had much contact with Eastern and Western Slavs to the north of the Danube.[185]

Immigrationist scholars underline that the population of the Roman provinces to the south of the Danube was "thoroughly Latinized".[185] Romanian has common features with idioms spoken in the Balkans (especially with Albanian and Bulgarian), suggesting that these languages developed side by side for centuries.[185][186] Southern Slavic loanwords also abound in Romanian.[185] Literary sources attest the presence of significant Romance-speaking groups in the Balkans (especially in the mountainous regions) in the Middle Ages.[187][188] Dozens of place names of Romanian origin can still be detected in the same territory.[82] The Romanians became Orthodox Christians and adopted Old Church Slavonic as liturgical language, which could hardly happen in the lands to the north of the Danube after 864 (when Boris I of Bulgaria converted to Christianity).[189][27] Early medieval documents unanimously describe the Vlachs as a mobile pastoralist population.[190] Slavic and Hungarian loanwords also evince that the Romanians' ancestors adopted a settled way of life only at a later phase of their ethnogenesis.[191]

Reliable sources refer to the Romanians' presence in the lands to the north of the Danube for the first time in the 1160s. No place names of Romanian origin were recorded where early medieval settlements existed in this area.[192] Here, the Romanians adopted Hungarian, Slavic and German toponyms, also indicating that they arrived after the Saxons settled in southern Transylvania in the mid-12th century.[193][194] The Romanians initially formed scattered communities in the Southern Carpathians, but their northward expansion is well-documented from the second half of the 13th century.[195][196] Both the monarchs and individual landowners (including Roman Catholic prelates) promoted their immigration, because the Romanian sheep-herders strengthened the defense of the borderlands and colonised areas which could not be brought into cultivation.[197][198] The Romanians adopted a sedentary way of life after they started settling on the edge of lowland villages in the mid-14th century.[199] Their immigration continued during the following centuries and they gradually took possession of the settlements in the plains which had been depopulated by frequent incursions.[200][201]

Further theories

According to the "admigration theory", proposed by Dimitrie Onciul, the formation of the Romanian people occurred in the former "Dacia Traiana" province, and in the central regions of the Balkan Peninsula.[202][203][204] However, the Balkan Vlachs' northward migration ensured that these centers remained in close contact for centuries.[202][205]

[Centuries] after the fall of the Balkan provinces, a pastoral Latin-Roman tradition served as the point of departure for a Valachian-Roman ethnogenesis. This kind of virtuality – ethnicity as hidden potential that comes to the fore under certain historical circumstances – is indicative of our new understanding of ethnic processes. In this light, the passionate discussion for or against Roman-Romanian continuity has been misled by a conception of ethnicity that is far too inflexible

— Pohl, Walter (1998)[206]

Evidence

Written sources

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

Romania in Antiquity and the Middle Ages

In the 5th century BC, Herodotus was the first author to write a detailed account of the natives of south-eastern Europe.[207][208] In connection with a Persian campaign in 514 BC, he mentions the Getae, which he called "the most courageous and upright Thracian tribe".[209][210] Strabo wrote that the language of the Dacians was "the same as that of the Getae".[211][212]

Literary tradition on the conquest of Dacia was preserved by 3-4 Roman scholars.[213] Cassius Dio wrote that "numerous Dacians kept transferring their allegiance"[214] to Emperor Trajan before he commenced his war against Decebal.[215] Lucian of Samosata, Eutropius, and Julian the Apostate unanimously attest the memory of a "deliberate ethnic cleansing" that followed the fall of the Dacian state.[216] For instance, Lucian of Samosata who cites Emperor Trajan's physician Criton of Heraclea states that the entire Dacian "people was reduced to forty men".[217] In fact, Thracian or possibly Dacian names represent about 2% of the approximately 3,000 proper names known from "Dacia Traiana".[218] Bitus, Dezibalos and other characteristic Dacian names were only recorded in the empire's other territories, including Egypt and Italy.[218][219] Constantin Daicoviciu, Dumitru Protase, Dan Ruscu and other historians have debated the validity of the tradition of the Dacians' extermination. They state that it only refers to the men's fate or comes from Eutropius's writings to provide an acceptable explanation for the massive colonisation that followed the conquest.[220] Indeed, Eutropius also reported that Emperor Trajan transferred to the new province "vast numbers of people from all over the Roman world".[220][221] Onosmatic evidence substantiates his words: about 2,000 Latin, 420 Greek, 120 Illyrian, and 70 Celtic names are known from the Roman period.[218][222]

Barbarian attacks against "Dacia Traiana" were also recorded.[223] For instance, "an inroad of the Carpi"[224] forced Emperor Galerius's mother to flee from the province in the 240s.[225] Aurelius Victor, Eutropius and Festus stated that Dacia "was lost"[226][227][228] under Emperor Gallienus (r. 253–268).[229][230] The Augustan History and Jordanes refer to the Roman withdrawal from the province in the early 270s.[231] The Augustan History says that Emperor Aurelian "led away both soldiers and provincials"[232] from Dacia in order to repopulate Illyricum and Moesia.[231][233]

In less than a century, the one-time province was named "Gothia",[234] by authors including the 4th-century Orosius.[235] The existence of Christian communities in Gothia is attested by the Passion of Sabbas, "a Goth by race" and by the martyrologies of Wereka and Batwin, and other Gothic Christians.[236][237] Large number of Goths, Taifali, and according to Zosimus "other tribes that formerly dwelt among them"[238] were admitted into the Eastern Roman Empire following the invasion of the Huns in 376.[239][240] In contrast with these peoples, the Carpo-Dacians "were mixed with the Huns".[241][242] Priscus of Panium, who visited the Hunnic Empire in 448,[243] wrote that the empire's inhabitants spoke either Hunnic or Gothic,[244] and that those who had "commercial dealings with the western Romans"[245] also spoke Latin.[244] He also mentions the local name of two drinks, medos and kam.[245][246] Emperor Diocletian's Edict on Prices states that the Pannonians had a drink named kamos.[247] Medos may have also been an Illyrian term, but a Germanic explanation cannot be excluded.[247]

The 6th-century author Jordanes who called Dacia "Gepidia"[248][249] was the first to write of the Antes and Slavenes.[250] He wrote that the Slavenes occupied the region "from the city of Noviodunum and the lake called Mursianus" to the river Dniester, and that the Antes dwelled "in the curve of the sea of Pontus".[251][252] Procopius wrote that the Antes and the Slaveni spoke "the same language, an utterly barbarous tongue".[253][254] He also writes of an Antian who "spoke in the Latin tongue".[255][256] The late 7th-century author Ananias of Shirak wrote in his geography that the Slavs inhabited the "large country of Dacia"[257] and formed 25 tribes.[258] In 2001, Florin Curta argues, that the Slaveni ethnonym may have only been used "as an umbrella-term for various groups living north of the Danube frontier, which were neither 'Antes', nor 'Huns' or 'Avars' ".[259]

The Ravenna Geographer wrote about a Dacia "populated by the [...] Avars",[260][261] but written sources from the 9th and 10th centuries are scarce.[262] The Royal Frankish Annals refers to the Abodrites living "in Dacia on the Danube as neighbors of the Bulgars"[263] around 824.[264] The Bavarian Geographer locates the Merehanii next to the Bulgars.[265] By contrast, Alfred the Great wrote of "Dacians, who were formerly Goths", living to the south-east of the "Vistula country" in his abridged translation (ca. 890) of Paulus Orosius' much earlier work Historiae Adversus Paganos written around 417.[266] Emperor Constantine VII's De Administrando Imperio contains the most detailed information on the history of the region in the first decades of the 10th century.[267] It reveals that Patzinakia,[268] the Pechenegs' land was bordered by Bulgaria on the Lower Danube around 950,[269] and the Hungarians lived on the rivers Criş, Mureş, Timiş, Tisa and Toutis at the same time.[270][271] That the Pechenegs's land was located next to Bulgaria is confirmed by the contemporary Abraham ben Jacob.[272]

The Gesta Hungarorum from around 1150 or 1200[273] is the first chronicle to write of Vlachs in the intra-Carpathian regions.[274][275] Its anonymous author stated that the Hungarians encountered "Slavs, Bulgarians, Vlachs, and the shepherds of the Romans"[276] when invading the Carpathian Basin around 895.[163] He also wrote of Gelou, "a certain Vlach"[277] ruling Transylvania, a land inhabited by "Vlachs and Slavs".[278][279][61] In his study on medieval Hungarian chronicles, Carlile Aylmer Macartney concluded that the Gesta Hungarorum did not prove the presence of Romanians in the territory, since its author's "manner is much rather that of a romantic novelist than a historian".[280] In contrast, Alexandru Madgearu, in his monography dedicated to the Gesta, stated that this chronicle "is generally credible", since its narration can be "confirmed by the archaeological evidence or by comparison with other written sources" in many cases.[281]

The late 12th-century chronicle of Niketas Choniates contains another early reference to Vlachs living north of the Danube.[282] He wrote that they seized the future Byzantine emperor, Andronikos Komnenos when "he reached the borders of Halych" in 1164.[85][283] Thereafter, information on Vlachs from the territory of present-day Romania abounds.[284] Choniates mentioned that the Cumans crossed the Lower Danube "with a division of Vlachs"[285] from the north to launch a plundering raid against Thrace in 1199.[286][287] Pope Gregory IX wrote about "a certain people in the Cumanian bishopric called Walati" and their bishops around 1234.[288] A royal charter of 1223 confirming a former grant of land is the earliest official document of Romanians in Transylvania.[284] It refers to the transfer of land previously held by them to the monastery of Cârța, which proves that this territory had been inhabited by Vlachs before the monastery was founded.[289] According to the next document, the Teutonic Knights received the right to pass through the lands possessed by the Székelys and the Vlachs in 1223. Next year the Transylvanian Saxons were entitled to use certain forests together with the Vlachs and Pechenegs.[290] Simon of Kéza knew that the Székelys "shared with the Vlachs" the mountains, "mingling with them"[291] and allegedly adopting the Vlachs' alphabet.[292]

A charter of 1247 of King Béla IV of Hungary lists small Romanian polities existing north of the Lower Danube.[41] Thomas Tuscus mentioned Vlachs fighting against the Ruthenes in 1276 or 1277.[48][293] References to Vlachs living in the lands of secular lords and prelates in the Kingdom of Hungary appeared in the 1270s.[294] First the canons of the cathedral chapter in Alba Iulia received a royal authorization to settle Romanians to their domains in 1276.[295] Thereafter, royal charters attest the presence of Romanians in more counties, for instance in Zărand from 1318, in Bihor and in Maramureș from 1326, and in Turda from 1342.[296] The first independent Romanian state, the Principality of Wallachia, was known as Oungrovlachia ("Vlachia near Hungary") in Byzantine sources, while Moldavia received the Greek denominations Maurovlachia ("Black Vlachia") or Russovlachia ("Vlachia near Russia").[297]

Balkan Vlachs

The words "torna, torna fratre"[298] recorded in connection with a Roman campaign across the Balkan Mountains by Theophylact Simocatta and Theophanes the Confessor evidence the development of a Romance language in the late 6th century.[299] The words were shouted "in native parlance"[300] by a local soldier in 587 or 588.[299][301] When narrating the rebellion of Kuber and his people against the Avars, the 7th-century Miracles of St. Demetrius mentions that a close supporter of his, Mauros[302] spoke four languages, including "our language" (Greek) and "that of the Romans" (Latin).[303] Kuber led a population of mixed origin – including the descendants of Roman provincials[304] who had been captured in the Balkans in the early 7th century – from the region of Sirmium to Thessaloniki around 681.[305]

John Skylitzes's chronicle contains one of the earliest records on the Balkan Vlachs.[306][307] He mentions that "some vagabond Vlachs"[308] killed David, one of the four Cometopuli brothers between Kastoria and Prespa in 976.[309][310] After the Byzantine occupation of Bulgaria, Emperor Basil II set up the autocephalous Archbishopric of Ohrid with the right from 1020 to collect income "from the Vlachs in the whole of theme of Bulgaria".[311][312] The late 11th-century Kekaumenos relates that the Vlachs of the region of Larissa had "the custom of having their herds and families stay in high mountains and other really cold places from the month of April to the month of September".[313][314] A passing remark by Anna Comnena reveals that nomads of the Balkans were "commonly called Vlachs" around 1100.[315][316][317] Occasionally, the Balkan Vlachs cooperated with the Cumans against the Byzantine Empire, for instance by showing them "the way through the passes"[318] of the Stara Planina in the 1090s.[319][320]

Most information on the 1185 uprising of the Bulgars and Vlachs and the subsequent establishment of the Second Bulgarian Empire is based on Niketas Choniates's chronicle.[321] He states that it was "the rustling of their cattle"[322] which provoked the Vlachs to rebel against the imperial government.[43][323] Besides him, Ansbert, and a number of other contemporary sources refer to the Vlach origin of the Asen brothers who initiated the revolt.[note 3][324] The Vlachs' pre-eminent role in the Second Bulgarian Empire is demonstrated by Blacia, and other similar denominations under which the new state was mentioned in contemporary sources.[325] The Annales Florolivienses, the first such source,[326] mentions the route of Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa "through Hungary, Russia, Cumania, Vlakhia, Durazzo, Byzantium and Turkey" during his crusade of 1189.[326] Pope Innocent III used the terms "Vlachia and Bulgaria" jointly when referring to the whole territory of the Second Bulgarian Empire.[327] Similarly, the chronicler Geoffrey of Villehardouin refers to the Bulgarian ruler Kaloyan as "Johanitsa, the king of Vlachia and Bulgaria".[327][328] The Icelandic author Snorri Sturluson mentioned the Balkan Vlachs' territory as Blokumannaland in his early 13th-century text Heimskringla.[282][329] William of Rubruck distinguished Bulgaria from Blakia.[327] He stated that "Bulgaria, Blakia and Slavonia were provinces of the Greeks",[330] implying that his Blakia was also located south of the Danube.[327] Likewise, the "Vlach lands" mentioned in the works of Abulfeda, Ibn Khaldun and other medieval Muslim authors are identical with Bulgaria.[331]

Uncertain references

The 10th-century Muslim scholars, Al-Muqaddasi and Ibn al-Nadim mentioned the Waladj and the Blaghā, respectively in their lists of peoples.[332] The lists also refer to the Khazars, Alans, and Greeks, and it is possible that the two ethnonyms refer to Vlachs dwelling somewhere in south-eastern Europe.[333] For instance, historian Alexandru Madgearu says that Al-Muqaddasi's work is the first reference to Romanians living north of the Danube.[334] Victor Spinei writes that a runestone which was set up around 1050 contains the earliest reference to Romanians living east of the Carpathians.[335] It refers to Blakumen who killed a Varangian merchant at an unspecified place.[335] The 11th-century Persan writer, Gardizi, wrote about a Christian people called N.n.d.r inhabiting the lands along the Danube.[336] Historian Adolf Armbruster identified this people as Vlachs.[336] In Hungarian, the Bulgarians were called Nándor in the Middle Ages.[337]

The Russian Primary Chronicle from 1113 contains possible references to Vlachs in the Carpathian Basin.[338][339] It relates how the Volokhi seized "the territory of the Slavs"[340] and were expelled by the Hungarians.[341][342] Therefore, the Slavs' presence antedates the arrival of the Volokhi in the chronicle's narration.[339] Madgearu and many other historians argue that the Volokhi are Vlachs, but the Volokhi have also been identified with either Romans or Franks annexing Pannonia (for instance, by Lubor Niederle and by Dennis Deletant respectively).[339][343][344]

The poem Nibelungenlied from the early 1200s mentions one "duke Ramunc of Wallachia"[345] in the retinue of Attila the Hun.[282][346] The poem alludes to the Vlachs along with the Russians, Greeks, Poles and Pechenegs, and may refer to a "Wallachia" east of the Carpathians.[347] The identification of the Vlachs and the Bolokhoveni of the Hypatian Chronicle whose land bordered on the Principality of Halych is not unanimously accepted by historians (for instance, Victor Spinei refuses it).[348]

Archaeological data

This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. This template was placed by Borsoka (talk · contribs). If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by Cealicuca (talk | contribs) 5 years ago. (Update timer) |

To the north of the Lower Danube

| Period | Cluj (1992) |

Alba (1995) |

Mureş (1995) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Roman (5th century BC–1st century AD) | 59 (20%) |

111 (33%) |

252 (28%) |

| Roman (106–270s) | 144 (50%) |

155 (47%) |

332 (37%) |

| 270s–390s | 40 (14%) |

67 (20%) |

79 (9%) |

| 5th century | 49 (6%) | ||

| 6th century | 48 (6%) | ||

| 7th century | 40 (5%) | ||

| 8th century | 39 (5%) | ||

| 9th century | 19 (2%) | ||

| 10th century | 16 (2%) | ||

| 11th century–14th century | 47 (16%) |

||

| Total number | 290 | 333 | 874 |

Tumuli erected for a cremation rite appeared in Oltenia and in Transylvania around 100 BC, thus preceding the emergence of the Dacian kingdom.[350] Their rich inventory has analogies in archaeological sites south of the Danube.[350] Although only around 300 graves from the next three centuries have been unearthed in Romania, they represent multiple burial rites, including ustrinum cremation[351] and inhumation.[352] New villages in the Mureș valley prove a demographic growth in the 1st century BC.[353] Fortified settlements were erected on hilltops,[353] mainly in the Orăştie Mountains,[351] but open villages remained the most common type of settlement.[354] In contrast with the finds of 25,000 Roman denarii and their local copies, imported products were virtually missing in Dacia.[355] The interpretations of Geto-Dacian archaeological findings are problematic because they may be still influenced by methodological nationalism.[356]

The conquering Romans destroyed all fortresses[357] and the main Dacian sanctuaries around 106 AD.[358] All villages disappeared because of the demolition.[357] Roman settlements built on the location of former Dacian ones have not been identified yet.[357] However, the rural communities at Boarta, Cernat, and other places used "both traditional and Roman items", even thereafter.[359] Objects representing local traditions have been unearthed at Roman villas in Aiudul de Sus, Deva and other places as well.[360] A feature of the few types of native pottery which continued to be produced in Roman times is the "Dacian cup", a mostly hand-made mug with a wide rim,[361] which was used even in military centers.[362] The use of a type of tall cooking pot indicates the survival of traditional culinary practices as well.[362]

Colonization and the presence of military units gave rise to the emergence of most towns in "Dacia Traiana": for instance, Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa was founded for veterans, Apulum and Potaissa started to develop as canabae.[363] Towns were the only places where the presence of Christians can be assumed based on objects bearing Christian symbolism, including a lamp and a cup decorated with crosses, which have been dated to the Roman period.[364] Rural cemeteries characterized by burial rites with analogies in sites east of the Carpathians attest to the presence of immigrant "barbarian" communities, for instance, at Obreja and Soporu de Câmpie.[365] Along the northwestern frontiers of the province, "Przeworsk" settlements were unearthed at Boineşti, Cehăluţ, and other places.[366]

Archaeological finds suggest that attacks against Roman Dacia became more intensive from the middle of the 3rd century: an inscription from Apulum hails Emperor Decius (r. 249–251) as the "restorer of Dacia"; and coin hoards ending with pieces minted in this period have been found.[367] Inscriptions from the 260s attest that the two Roman legions of Dacia were transferred to Pannonia Superior and Italy.[368] Coins bearing the inscription "DACIA FELIX" minted in 271 may reflect that Trajan's Dacia still existed in that year,[368] but they may as well refer to the establishment of the new province of "Dacia Aureliana".[369]

The differentiation of archaeological finds from the periods before and after the Roman withdrawal is not simple, but Archiud, Obreja, and other villages produced finds from both periods.[370] Towns have also yielded evidence on locals staying behind.[130] For instance, in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegatusa, at least one building was inhabited even in the 4th century, and a local factory continued to produce pottery, although "in a more restricted range".[371] Roman coins from the 3rd and 4th centuries, mainly minted in bronze, were found in Banat where small Roman forts were erected in the 290s.[372] Coins minted under Emperor Valentinian I (r. 364–375) were also found in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa, where the gate of the amphitheater was walled at an uncertain date.[373] A votive plate found near a spring at Biertan bears a Latin inscription dated to the 4th century, and has analogies in objects made in the Roman Empire.[374] Whether this donarium belonged to a Christian missionary, to a local cleric or layman or to a pagan Goth making an offering at the spring is still debated by archaeologists.[375]

A new cultural synthesis, the "Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov culture", spread through the plains of Moldavia and Wallachia in the early 4th century.[376] It incorporated elements of the "Wielbark culture" of present-day Poland and of local tradition.[377][378] More than 150 "Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov" settlements[379] suggest that the territory experienced a demographic growth.[376] Three sites in the Eastern Carpathians already inhabited in the previous century[note 4] prove the natives' survival as well.[380] Growing popularity of inhumation burials also characterizes the period.[381] "Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov" cemeteries from the 4th century were also unearthed in Transylvania.[382] Coin hoards ending with pieces from the period between 375 and 395 unearthed at Bistreţ, Gherla, and other settlements[383] point to a period of uncertainty.[384] Featuring elements of the "Przeworsk" and "Sântana de Mureş-Chernyakhov" cultures also disappeared around 400.[385] Archaeological sites from the next centuries have yielded finds indicating the existence of scattered communities bearing different traditions.[386] Again, cremation became the most widespread burial rite east of the Carpathians, where a new type of building – sunken huts with an oven in the corner – also appeared.[387] The heterogeneous vessel styles were replaced by the more uniform "Suceava-Şipot" archaeological horizon of hand made pottery from the 550s.[388]

In contrast with the regions east of the Carpathians, Transylvania experienced the spread of the "row grave" horizon of inhumation necropolises in the 5th century,[389] also known from the same period in Austria, Bohemia, Transdanubia and Thuringia.[390] At the same time, large villages appeared in Crișana and Transylvania,[391] in most cases in places where no earlier habitation has yet been proven.[392] Moreover, imported objects with Christian symbols, including a fish-shaped lamp from Lipova, and a "Saint Menas flask" from Moigrad, were unearthed.[393] However, only about 15% of the 30 known "row grave" cemeteries survived until the late 7th century.[394] They together form the distinct "Band-Noşlac" group of graveyards[17] which also produced weapons and other objects of Western or Byzantine provenance.[395]

The earliest examples in Transylvania of inhumation graves with a corpse buried, in accordance with nomadic tradition, with remains of a horse were found at Band.[396] The "Gâmbaş group" of cemeteries[17] emerged in the same period, producing weapons similar to those found in the Pontic steppes.[397] Sunken huts appeared in the easternmost zones of Transylvania around 7th century.[398] Soon the new horizon of "Mediaș" cemeteries,[17] containing primarily cremation graves, spread along the rivers of the region.[399] The "Nușfalău-Someşeni" cemeteries[17] likewise follow the cremation rite, but they produced large tumuli with analogies in the territories east of the Carpathians.[399]

In the meantime, the "Suceava-Şipot horizon" disappeared in Moldavia and Wallachia, and the new "Dridu culture" emerged on both sides of the Lower Danube around 700.[152][400] Thereafter the region again experienced demographic growth.[401] For instance, the number of settlements unearthed in Moldavia grew from about 120 to about 250 from the 9th century to the 11th century.[402] Few graveyards yielding artifacts similar to "Dridu cemeteries" were also founded around Alba Iulia in Transylvania.[400] The nearby "Ciumbrud group" of necropolises of inhumation graves point at the presence of warriors.[403] However, no early medieval fortresses unearthed in Transylvania, including Cluj-Mănăştur, Dăbâca, and Şirioara, can be definitively dated earlier than the 10th century.[404]

Small inhumation cemeteries of the "Cluj group",[17] characterized by "partial symbolic horse burials", appeared at several places in Banat, Crişana, and Transylvania including at Biharia, Cluj and Timişoara around 900.[405] Cauldrons and further featuring items of the "Saltovo-Mayaki culture" of the Pontic steppes were unearthed in Alba Iulia, Cenad, Dăbâca, and other settlements.[406] A new custom of placing coins on the eyes of the dead was also introduced around 1000.[406] "Bijelo Brdo" cemeteries, a group of large graveyards with close analogies in the whole Carpathian Basin, were unearthed at Deva, Hunedoara and other places.[407] The east–west orientation of their graves may reflect Christian influence,[406] but the following "Citfalău group" of huge cemeteries that appeared in royal fortresses around 1100 clearly belong to a Christian population.[408]

Romanian archaeologists propose that a series of archaeological horizons that succeeded each other in the lands north of the Lower Danube in the early Middle Ages support the continuity theory.[409][410] In their view, archaeological finds at Brateiu (in Transylvania), Ipotești (in Wallachia) and Costișa (in Moldavia) represent the Daco-Roman stage of the Romanians' ethnogenesis which ended in the 6th century.[410][411] The next ("Romanic") stage can be detected through assemblages unearthed in Ipotești, Botoșana, Hansca and other places which were dated to the 7th-8th centuries.[410] Finally, the Dridu culture is said to be the evidence for the "ancient Romanian" stage of the formation of the Romanian people.[410] In contrast to these views, Opreanu emphasizes that the principal argument of the hypothesis—the presence of artefacts imported from the Roman Empire and their local copies in allegedly "Daco-Roman" or "Romanic" assemblages—is not convincing, because close contacts between the empire and the neighboring Slavs and Avars is well-documnted.[152] He also underlines that Dridu culture developed after a "cultural discontinuity" that followed the disappearance of the previous horizons.[152] Regarding both the Slavs and Romanians as sedentary populations, Alexandru Madgearu also underlines that the distinction of "Slavic" and "Romanian" artefacts is difficult, because archaeologists can only state that these artifacts could hardly be used by nomads.[156] He proposes that "The wheel-made pottery produced on the fast wheel (as opposed to the tournette), which was found in several settlements of the eighth, ninth, and tenth centuries, may indicate the continuation of Roman traditions" in Transylvania.[157]

Thomas Nägler proposes that a separate "Ciugud culture" represents the Vlach population of southern Transylvania.[412] He also argues that two treasures from Cârțișoara and Făgăraș also point at the presence of Vlachs.[412] Both hoards contain Byzantine coins ending with pieces minted under Emperor John II Komnenos who died in 1143.[413] Tudor Sălăgean proposes that these treasures point at a local elite with "at least" economic contacts with the Byzantine Empire.[413] Paul Stephenson argues that Byzantine coins and jewellery from this period, unearthed at many places in Hungary and Romania, are connected to salt trade.[414]

-

Ruins of a Dacian sanctuary at Sarmizegetusa Regia

-

Ruins of the Roman amphitheatre at Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

-

Latin inscription in Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

-

The 4th-century Biertan Donarium with the Latin writing "EGO ZENOVIUS VOTUM POSVI" (=I, Zenovius, brought this offering)

Central and Northern Balkans

Fortified settlements built on hill-tops characterized the landscape in Illyricum before the Roman conquest.[415] In addition, huts built on piles formed villages along the rivers Sava and its tributaries.[416] Roman coins unearthed in the northwestern regions may indicate that trading contacts between the Roman Empire and Illyricum began in the 2nd century BC, but piracy, quite widespread in this period, could also contribute to their cumulation.[417] The first Roman road in the Balkans, the Via Egnatia which linked Thessaloniki with Dyrrhachium was built in 140 BC.[418] Byllis and Dyrrhachium, the earliest Roman colonies were founded a century later.[419] The Romans established a number of colonies for veterans and other towns, including Emona, Siscia, Sirmium and Iovia Botivo, in the next four centuries.[420]

Hand-made pottery of local tradition remained popular even after potter's wheel was introduced by the Romans.[421] Likewise, as it is demonstrated by altars dedicated to Illyrian deities at Bihać and Topusko, native cults survived the Roman conquest. [422] Latin inscriptions on stone monuments prove the existence of a native aristocracy in Roman times.[423] Native settlements flourished in the mining districts in Upper Moesia up until the 4th century.[424] Native names and local burial rites only disappeared in these territories in the 3rd century.[425] In contrast, the frontier region along the Lower Danube in Moesia had already in the 1st century AD transformed into "a secure Roman-only zone" (Brad Bartel), from where the natives were moved.[426]

Emperors born in Illyricum, a common phenomenon of the period,[427] erected a number of imperial residences at their birthplaces.[428] For instance, a palace was built for Maximianus Herculius near Sirmium, and another for Constantine the Great in Mediana.[429] New buildings, rich burials and late Roman inscriptions show that Horreum Margi, Remesiana, Siscia, Viminacium, and other centers of administration also prospered under these emperors.[430] Archaeological research – including the large cemeteries unearthed at Ulpianum and Naissus – shows that Christian communities flourished in Pannonia and Moesia from the 4th century.[431] Inscriptions from the 5th century point at Christian communities surviving the destruction brought by the Huns at Naissus, Viminacium and other towns of Upper Moesia.[432] In contrast, villae rusticae which had been centers of agriculture from the 1st century disappeared around 450.[433] Likewise, forums, well planned streets and other traditional elements of urban architecture ceased to exist.[434] For instance, Sirmium "disintegrated into small hamlets emerging in urban areas that had not been in use until then" after 450.[435] New fortified centers developed around newly erected Christian churches in Sirmium, Novae,[436] and many other towns by around 500.[435] In contrast with towns, there are only two archaeological sites[note 5] from this period identified as rural settlements.[437][438]

Under Justinian the walls of Serdica, Ulpianum and many other towns were repaired.[439] He also had hundreds of small forts erected along the Lower Danube,[440] at mountain passes across the Balkan Mountains and around Constantinople.[16] Inside these forts small churches and houses were built.[441] Pollen analysis suggest that the locals cultivated legumes within the walls, but no other trace of agriculture have been identified.[441] They were supplied with grain, wine and oil from distant territories, as it is demonstrated by the great number of amphorae unearthed in these sites which were used to transport these items to the forts.[442] Most Roman towns and forts in the northern parts of the Balkans were destroyed in the 570s or 580s.[443] Although some of them were soon restored, all of them were abandoned, many even "without any signs of violence", in the early 7th century.[443]

The new horizon of "Komani-Kruja" cemeteries emerged in the same century.[444] They yielded grave goods with analogies in many other regions, including belt buckles widespread in the whole Mediterranean Basin, rings with Greek inscriptions, pectoral crosses, and weapons similar to "Late Avar" items.[445][446] Most of them are situated in the region of Dyrrhachium, but such cemeteries were also unearthed at Viničani and other settlements along the Via Egnatia.[447] "Komani-Kruja" cemeteries ceased to exist in the early 9th century.[448] John Wilkes proposes that they "most likely" represent a Romanized population,[449] while Florin Curta emphasizes their Avar features.[450] Archaeological finds connected to a Romance-speaking population have also been searched in the lowlands to the south of the Lower Danube.[451] For instance, Uwe Fiedler mentions that inhumation graves yielding no grave goods from the period between the 680s and the 860s may represent them, although he himself rejects this theory.[451]

Linguistic approach

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

Development of Romanian

The formation of the Common Romanian language from Vulgar Latin started in the 6th or 7th centuries and was completed in the 8th century.[452] Common Romanian split into four variants (Daco-Romanian, Macedo-Romanian, Megleno-Romanian and Istro-Romanian) during the 10th-12th centuries.[453][66][454] Unlike other Romance languages, the Romanian subdialects spoken to the north of the Danube display a "remarkable unity".[455] Primarily the use of different words differentiate them, because their phonology is quite uniform.[456] Whether the shepherds seasonal movements between the mountains and the lowlands secured the preservation of language unity,[455] or the levelling effect of migrations gave rise to the development of a uniform idiom,[note 6] cannot be decided.[456]

There are around 100 Romanian words with a possible substratum origin, but the language from which they were transferred cannot be determined.[66] Around 30% of these words[note 7] represent the specific vocabulary of sheep- and goat-breeding.[457] Moreover, about 70 possible substrate words,[note 8] have Albanian cognates.[457][458] Romanian, Albanian and other languages sharing some common morphological and syntactic characteristics form together a supposed "Balkan linguistic union".[66] These common features include the postposed definite articles[note 9] and the merger of the dative case and possessive case.[76][459] Whether they represent a common substrate language, or convergent development is still a matter of debate among linguists.[66][76]

Hundreds of words that have presumably been inherited from Latin can only be traced back to hypotetical Latin words which were reconstructed based on their Romanian form.[460] Words of Latin origin were also borrowed from Slavic languages.[note 10][456][461]

In addition to words of Latin or of possible substratum origin, loanwords make up more than 40% (according to certain estimations 60-80%)[57][58] of the Romanian vocabulary.[462] Linguist Gabriela P. Dindelegan underlines that contacts with other peoples has not modified the "Latin structure of Romanian" and the "non-Latin grammatical elements" borrowed from other languages were "adapted to and assimilated by the Romance pattern".[57] No loanwords of East Germanic (Gothic or Gepid) origin have so far been proven.[66] In the Middle Ages, Slavic languages had a substantial influence on Romanian, but a significant number of words were borrowed from Turkic, Hungarian, Greek or German languages.[463][464][465]

The ratio of Slavic loanwords is still about 14%, although a strong "re-latinization" process has decreased their number since the 19th century.[466][467] For instance, the number of Slavic borrowings exceeds that of the inherited terms in several semantic fields, including that of the natural environment[52] The names for most species of fish of the Danube[note 11] and of a number of other animals living in Romania[note 12] are of Slavic origin.[468] Linguists often attribute the development of about 10 phonological and morphological features of the Romanian language to Slavic influence, but there is no consensual view.[469] For instance, contacts with Slavic-speakers allegedly contributed to the appearance of the semi-vowel [y] before the vowel [e] at the beginning of basic words and to the development of the vocative case in Romanian.[470] Linguist Kim Schulte says, the significant common lexical items and the same morpho-syntactic structures of the Romanian and Bulgarian (and Macedonian) languages "indicates that there was a high decree of bilingualism in this mixed population".[76]

All neighboring peoples adopted a number of Romanian words connected to goat- and sheep-breeding.[471] Romanian loanwords are rare in standard Hungarian, but abound in its Transylvanian dialects.[472] In addition to place names and elements of the Romanian pastoral vocabulary, the Transylvanian Hungarians primarily adopted dozens of Romanian ecclesiastic and political terms to refer to specific Romanian institutions already before the mid-17th centuries.[note 13][473] The adoption of the Romanian terminology shows that the traditional Romanian institutions, which followed Byzantine patterns, significantly differed from their Hungarian counterparts.[472]

Romanian place names

| |||

| The names of the main rivers—Someș, Mureș and Olt—are inherited from Antiquity. | |||

| River | Tributaries | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Someș | Beregszó (H) > Bârsău; Lápos (H) > Lăpuș; Hagymás (H) > Hășmaș ; Almás (H) > Almaș; Egregy (H) > Agrij; Szilágy (H) > Sălaj; *Krasъna (S) > (? Kraszna (H)) > **Crasna | ||

| Lăpuș | Kékes (H) > Chechișel; *Kopalnik (S) > Cavnic | ||

| Crasna | ? > Zilah (H) > Zalău; Homoród (H) > Homorod | ||

| Someșul Mic | Fenes (H) > Feneș; Füzes (H) > Fizeș; Kapus (H) > Căpuș; Nádas (H) > Nadăș; Fejérd (H) > Feiurdeni; *Lovъna (S) > Lóna (H) > Lonea; * ? (S) > Lozsárd (H) > Lujerdiu | ||

| Someșul Mare | *Rebra (S) > Rebra; *Solova (S) > Sălăuța; Széples (H) > Țibleș; *Ielšava (S) > Ilosva (H) > Ilișua; *Ilva (S) > Ilva; Sajó (H) > Șieu; *Tiha (S) > Tiha | ||

| Șieu | ? > Budak (H) > Budac; *Bystritsa (S) > Bistrița; *Lъknitsa (S) > Lekence (H) > Lechința | ||

| Mureș | Liuts (S/?) > Luț; *Lъknitsa (S) > Lekence (H) > Lechința; Ludas (H) > Luduș; Aranyos (H) > Arieș; *Vъrbova (S) > Gârbova; Gyógy (H) > Geoagiu; *Ampeios (?) > *Ompei (S) > (Ompoly (H) > Ampoi (G) ?) > ***Ampoi; Homoród (H) > Homorod; *Bistra (S) > Bistra; Görgény (H) > Gurghiu; Nyárád (H) > Niraj; * Tîrnava (S) > Târnava; Székás (H) > Secaș; Sebes (H) > Sebeș; *Strĕl (S) > Strei; *Čъrna (S) > Cerna | ||

| Arieș | ? > Abrud (H) > Abrud; *Trěskava (S) > Torockó (H) > Trascău; *Iar (S/?) > Iara; Hesdát (H) > Hășdate ; *Turjъ (S) > Tur; | ||

| Sebeș | Székás (H) > Secaș; * Dobra (S) > Dobra; * Bistra (S) > > Bistra | ||

| Olt | Kormos (H) > Cormoș; Homorod (H) > Homorod; * Svibiń (S) > Cibin; Hamorod (H) > Homorod River (Dumbrăvița); Sebes (H) > Sebeș ; Árpás (H) > Arpaș; Forrenbach (G) > Porumbacu | ||

| Cormoș | Vargyas (H) > Vârghiș | ||

| Cibin | *Hartobach (G) > Hârtibaciu | ||

| ? unknown, uncertain; * the form is not documented; ** the Crasna now flows into the Tisa, but it was the Someș's tributary; *** Linguist Marius Sala says that the Ampoi form was directly inherited from Antiquity.[159] | |||

Place names provide a significant proportion of modern knowledge of the extinct languages of South-eastern Europe.[475] Drobeta, Napoca, Porolissum, Sarmizegetusa and other settlements in "Dacia Traiana" bore names of local origin.[357] Some towns preserved their ancient names[note 14] in South-eastern Europe up until now, but the names of all Roman settlements attested in Roman Dacia in Antiquity disappeared.[181][476] The Romans adopted the native names of the main rivers[note 15] and these names survived the Roman withdrawal.[477][357][158] Linguists Oliviu and Nicolae Felecan write that the names were "uninterruptedly transmitted" from the Dacians to the Romans, and then to the Dacoromans.[158] Grigore Nandriș states that alone among the rivers in Dacia, the development of the name of the Criş from ancient Crisius would be in line with the phonetical evolution of Romanian.[478] Domnița Tomescu, Gottfried Schramm and other scholars say, the names of the rivers were preserved through a Slavic mediation.[160][479] The vowel shift from [a] to [u] or [o] experienced in the case of the rivers Mureş [< Maris], Olt [< Aluta], and Someş [< Samu(m)] is attested in the development of the Slavic languages, but is alien to Romanian and other tongues spoken in their regions.[480] Linguist Marius Sala says that these phonetic changes featured the late phase of the "Daco-Thracian" language, so they are "a conclusive argument" in favor of the continuity theory.[159] Schramm emphasizes that the [ʃ] ending of the modern names of the rivers could not be directly inherited from Latin, so they must have been transmitted from the local Dacians through Slavic mediation.[481] Dunărea, the Romanian name of the Danube may have developed from a supposed[482] Geto-Dacian *Donaris form.[483] However, this form is not attested in written sources.[482] Therefore, it is possible that the Romanians' ancestors in this case also adopted a Slavic name.[484] Based on the Repedea name for the upper course of the Bistrița (both meaning "quick"), Nandris writes that translations from Romanian into Slavic could also create Romanian hydronyms.[485]

More than a dozen of the tributaries of the large rivers had a name with probable Indo-European roots, suggesting a Dacian etymology.[note 16][486] The Slavic mediation during the transmission of the names of some of them is obvious.[note 17][160][487] The longer tributaries of the large rivers in Banat, Crişana and Transylvania which run through the most populated areas had modern names of German, Hungarian, Slavic or Turkic origin, which were also adopted by the Romanians.[480] For instance, the tributaries of the Someșul Mic River bear Hungarian[note 18] or Slavic[note 19] names,[480] while other tributaries bear local Dacian names.[note 20] Many of the smallest rivers and streams[note 21] bear names of Romanian origin.[488][160]

Place names of Slavic[note 22] or Hungarian[note 23] origin can be found in great number in medieval royal charters pertaining to Banat, Crișana, Maramureș, and Transylvania.[489] The names of Hungarian origin can be also found extensively in Moldavia, as a result of the Hungarian colonists settled during the medieval period.[490] In the mountains between the rivers Arieș and Mureș and in the territory the south of the Târnava Mare River, the Romanians and the Transylvanian Saxons directly (without Hungarian mediation) adopted the Slavic place names.[491] In almost all cases, when parallel Slavic-Hungarian or Slavic-German names are attested,[note 24] Romanians borrowed the Slavic forms, suggesting a long cohabitation of the Romanians and the Slavs or a close relationship between the two ethnic groups,[491] maybe already before the arrival of the Hungarians.[492]

The earliest toponym of certain Romanian origin in the same regions (Nucşoara) was recorded in 1359.[493] River names of Slavic origin[note 25] can also be found in the regions east and south of the Carpathians,[181] where Pecheneg or Cuman river names[note 26] also abound.[160][494] On the other hand, the name of the Vlaşca region in Wallachia refers to a Romance-speaking community in Slavic environment.[495]

Place names of Latin origin abound in the region of Lake Shkodër, along the rivers Drin and Fan and other territories to the north of the Viga Egnatia.[449] Gottfried Schramm argues that the names of at least eight towns in the region,[note 27] likewise suggest the one-time presence of a Romance speaking population in their vicinity.[496] Romanian place names can still be detected in Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia.[497] For example, such names[note 28] are concentrated in the wider region of the river Vlasina both in Bulgaria and Serbia,[82] and in Montenegro and the nearby territories.[note 29][497]

DNA / Paleogenetics

It has been suggested that this article should be split into a new article titled Genetic studies on Romanians. (discuss) (May 2016) |

The use of genetic data to supplement traditional disciplines has now become mainstream.[498] Given the palimpsest nature of modern genetic diversity, more direct evidence has been sought from ancient DNA (aDNA)[499] Although data from southeastern Europe is still at an incipient stage, general trends are already evident. For example, it has shown that the Neolithic revolution imparted a major demographic impact throughout Europe, disproving the Mesolithic adaptation scenario in its pure form. In fact, the arrival of Neolithic farmers might have been in at least two "waves", as suggested by a study which analysed mtDNA sequences from Romanian Neolithic samples.[500] This study also shows that 'M_NEO' (Middle Neolithic populations that lived in what is present-day Romania/Transylvania) and modern populations from Romania are very close, in contrast with Middle Neolithic and modern populations from Central Europe.[501] However, the samples extracted from Late Bronze Age DNA from Romania are farther from both of the previously mentioned.[502] The authors have stated "Nevertheless, studies on more individuals are necessary to draw definitive conclusions."[503] However, the study performed a "genetic analysis of a relatively large number of samples of Boian, Zau and Gumelniţa cultures in Romania (n = 41) (M_NEO)"[501]

Ancient DNA study[504] on human fossils found in Costişa, Romania, dating from de Bronze Age shows "close genetic kinship along the maternal lineage between the three old individuals from Costişa and some individuals found in other archeological sites dated from the Bronze and Iron Age. We also should note that the point mutations analyzed above are also found in Romanian modern population, suggesting that some old individuals from the human populations living on the Romanian land in the Bronze and Iron Age, could participate to a certain extent in the foundation of the Romanian genetic pool."

Another major demographic wave also occurred after 3000 BC from the steppe, postulated to be linked with the expansion of Indo-European languages.[505] Bronze and Iron Age samples from Hungary,[506] Bulgaria[507] and Romania,[508] however, suggest that this impact was less significant in Southeastern Europe than areas north of the Carpathians. In fact, in the abovementioned studies, the Bronze and Iron Age Balkan samples do not cluster with modern Balkan groups, but lie between Sardinians and other southwestern European groups, suggesting later phenomena (i.e. in Antiquity, Great Migration Period) caused shifts in population genetic structure. However, aDNA samples from southeastern Europe remain few, and only further sampling will allow a clear and diachronic overview of migratory and demographic trends.

No detailed analyses exist from the Roman and early medieval periods. Genome-wide analyses of extant populations show that intra-European diversity is a continuum (with the exception of groups like Finns, Sami, Basques and Sardinians). Romanians cluster amidst their Balkan and East European neighbours. However, they generally lie significantly closer to Balkan groups (Serbs, Macedonians, Bulgarians) than to central and eastern Europeans like Hungarians, Czechs, Poles and Ukrainians, and many lie in the center of the Balkan cluster, near Albanians, Greeks, and Bulgarians, while many former Yugoslav populations like Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes may draw closer to central European West Slavs. On autosomal studies, genetic distance of some Romanian samples to some Italians, such as Tuscans, is greater than that of the distance to neighboring Balkan peoples, but can in some cases still be relatively close when considering the overall European population structure; this likely reflects mainly ancient or prehistoric population patterns rather than more recent ties due to linguistic relationships. Geography plays one of the most important roles in determining European population structure.[509][510][511][512]

See also

Notes

- ^ For instance, both the Maramureș subdialect of Romanian and Arumanian have preserved the Latin word for sand (arină) instead of standard nisip, a Slavic loanword.

- ^ The map also depicts the "Jireček Line" (yellow), the Latin- and Greek-speaking territories (pink and blue areas, respectively), and the Albanians' supposed homeland (yellow areas).

- ^ Ansbert referred to one of the Asen brothers, Peter II of Bulgaria as "Kalopetrus Flachus".

- ^ Botoşana, Dodeşti, and Mănoaia (Heather, Matthews 1991, p. 91.).

- ^ At Novgrad in Bulgaria and at Slava Rusă in Romania (Barford 2001, p. 60.).

- ^ The development of a uniform language along the Western coasts if the USA demonstrates such a leveling effect.

- ^ For instance, cârlan ("yearling") [1], and urdă ("cheese made of whey") [2] (Spinei 2009, p. 228.).