Jefferson Davis: Difference between revisions

→Author: this and previous is a modificaton of a paragraph as per FAR. |

|||

| Line 263: | Line 263: | ||

[[File:Jefferson Davis, seated, facing front, during portrait session at Davis' home Beauvoir, near Biloxi, Mississippi LCCN2009633710.jpg|thumb|Photograph of Jefferson Davis at his home in [[Beauvoir (Biloxi, Mississippi)|Beauvoir]] by [[Edward Livingston Wilson|Edward Wilson]] ({{circa|1885}})|alt=bearded man looking forward with shuttered window in background]] |

[[File:Jefferson Davis, seated, facing front, during portrait session at Davis' home Beauvoir, near Biloxi, Mississippi LCCN2009633710.jpg|thumb|Photograph of Jefferson Davis at his home in [[Beauvoir (Biloxi, Mississippi)|Beauvoir]] by [[Edward Livingston Wilson|Edward Wilson]] ({{circa|1885}})|alt=bearded man looking forward with shuttered window in background]] |

||

In the 1870s, Davis became a life-time member of the [[Southern Historical Society]].{{sfnm|Cooper|2000|1pp=621–622|Starnes|1996|2p=188}} The society was devoted to presenting the [[Lost Cause]] explanation of the Civil War |

In the 1870s, Davis became a life-time member of the [[Southern Historical Society]].{{sfnm|Cooper|2000|1pp=621–622|Starnes|1996|2p=188}} The society was devoted to presenting the [[Lost Cause]] explanation of the Civil War{{sfn|Starnes|1996|pp=177–181}}. Initially, the society had scapegoated political leaders like Davis for losing the war,{{sfn|Starnes|1996|p=178}} but eventually shifted the blame for defeat to the former Confederate general [[James Longstreet]].{{sfn|Starnes|1996|pp=186–188}} Davis avoided public disputes regarding blame, but he did personally reply to [[Theodore Roosevelt]], who accused him of being a traitor like [[Benedict Arnold]]. Davis publicly maintained that he had done nothing wrong and had always upheld the Constitution.{{sfn|Davis|1991|pp=680–681}} |

||

Davis spent most of his final years at Beauvoir.{{sfn|Muldowny|1969|p=23}} In 1886, [[Henry W. Grady]], an advocate for the [[New South]], convinced Davis to lay the cornerstone for a monument to the Confederate dead in Montgomery, Alabama, and to attend the unveilings of statues memorializing Davis's friend [[Benjamin H. Hill]] in Savannah and the Revolutionary War hero [[Nathanael Greene]] in Atlanta.{{sfn|Collins|2005|pp=26–27}} The tour was a triumph for Davis and got extensive newspaper coverage, which emphasized national unity and the South's role as a permanent part of the United States. At each city and on stops along the way, large crowds came out to cheer Davis, solidifying his image as an icon of the Old South and the Confederate cause, and making him into a symbol for the New South.{{sfn|Muldowny|1969|p=31}} In October 1887, Davis participated in his last tour, traveling to the Georgia State Fair in [[Macon, Georgia]], for a grand reunion with Confederate veterans. He also continued writing. In the summer of 1888, he was encouraged by [[James Redpath]], editor of the ''[[North American Review]]'', to write a series of articles.{{sfnm|Collins|2005|1p=49|Cooper|2000|2p=644}} Redpath's encouragement also helped Davis to completed his final book ''[[A Short History of the Confederate States of America]]'' in October 1889;{{sfn|Davis|1991|p=682}} he also began dictating his memoirs, although they were never finished.{{sfnm|Cooper|2000|1p=645|Davis|1991|2p=683}} |

Davis spent most of his final years at Beauvoir.{{sfn|Muldowny|1969|p=23}} In 1886, [[Henry W. Grady]], an advocate for the [[New South]], convinced Davis to lay the cornerstone for a monument to the Confederate dead in Montgomery, Alabama, and to attend the unveilings of statues memorializing Davis's friend [[Benjamin H. Hill]] in Savannah and the Revolutionary War hero [[Nathanael Greene]] in Atlanta.{{sfn|Collins|2005|pp=26–27}} The tour was a triumph for Davis and got extensive newspaper coverage, which emphasized national unity and the South's role as a permanent part of the United States. At each city and on stops along the way, large crowds came out to cheer Davis, solidifying his image as an icon of the Old South and the Confederate cause, and making him into a symbol for the New South.{{sfn|Muldowny|1969|p=31}} In October 1887, Davis participated in his last tour, traveling to the Georgia State Fair in [[Macon, Georgia]], for a grand reunion with Confederate veterans. He also continued writing. In the summer of 1888, he was encouraged by [[James Redpath]], editor of the ''[[North American Review]]'', to write a series of articles.{{sfnm|Collins|2005|1p=49|Cooper|2000|2p=644}} Redpath's encouragement also helped Davis to completed his final book ''[[A Short History of the Confederate States of America]]'' in October 1889;{{sfn|Davis|1991|p=682}} he also began dictating his memoirs, although they were never finished.{{sfnm|Cooper|2000|1p=645|Davis|1991|2p=683}} |

||

Revision as of 18:07, 13 June 2023

Jefferson Davis | |

|---|---|

Photograph by Mathew Brady, c. 1859 | |

| President of the Confederate States | |

| In office February 22, 1862 – May 5, 1865 Provisional: February 18, 1861 – February 22, 1862 | |

| Vice President | Alexander H. Stephens |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| United States Senator from Mississippi | |

| In office March 4, 1857 – January 21, 1861 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Adams |

| Succeeded by | Adelbert Ames (1870) |

| In office August 10, 1847 – September 23, 1851 | |

| Preceded by | Jesse Speight |

| Succeeded by | John J. McRae |

| 23rd United States Secretary of War | |

| In office March 7, 1853 – March 4, 1857 | |

| President | Franklin Pierce |

| Preceded by | Charles Conrad |

| Succeeded by | John B. Floyd |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi's at-large district | |

| In office December 8, 1845 – October 28, 1846 Seat D | |

| Preceded by | Tilghman Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Henry T. Ellett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jefferson F. Davis June 3, 1808 Fairview, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | December 6, 1889 (aged 81) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Resting place | Hollywood Cemetery, Richmond, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | Southern Rights |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 6, including Varina |

| Education | United States Military Academy (BS) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Unit | 1st U.S. Dragoons |

| Commands | 1st Mississippi Rifles |

| Battles/wars | |

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the first and only president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War. He had previously served as the United States Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857 under President Franklin Pierce.

Davis, the youngest of ten children, was born in Fairview, Kentucky. He grew up in Wilkinson County, Mississippi, and also lived in Louisiana. His eldest brother Joseph Emory Davis secured the younger Davis's appointment to the United States Military Academy. After graduating, Jefferson Davis served six years as a lieutenant in the United States Army. He fought in the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) as the colonel of a volunteer regiment. Before the American Civil War, he operated in Mississippi a large cotton plantation which his brother Joseph had given him, and owned as many as 113 slaves. Although Davis argued against secession in 1858, he believed the states had an unquestionable right to leave the Union.

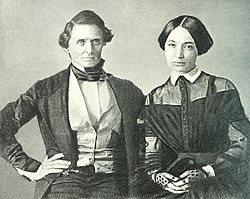

Davis married Sarah Knox Taylor, daughter of general and future President Zachary Taylor, in 1835, when he was 27. They both soon contracted malaria, and Sarah died after three months of marriage. Davis recovered slowly and had recurring bouts of illness throughout his life. At the age of 36, Davis married again, to 18-year-old Varina Howell. They had six children.

During the American Civil War, Davis guided Confederate policy and served as its commander in chief. When the Confederacy was defeated in 1865, Davis was captured, accused of treason, and imprisoned at Fort Monroe. He was never tried and was released after two years. Davis's legacy is intertwined with his role as President of the Confederacy. Immediately after the war, he was often blamed for the Confederacy's loss. After he was released, he was seen as a man who suffered unjustly for his commitment to the South, becoming a hero of the pseudohistorical Lost Cause of the Confederacy during the post-Reconstruction period. In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, his legacy as Confederate leader was celebrated in the South. In the twenty-first century, he is frequently criticized as a supporter of slavery and racism, and a number of the memorials created in his honor throughout the United States have been removed.

Early life

Birth and family background

Davis, who was named after then-President Thomas Jefferson,[1] was the youngest of ten children of Jane (née Cook) and Samuel Emory Davis.[2] Samuel Davis's father, Evan, who had a Welsh background, came to the colony of Georgia from Philadelphia.[3][a] Samuel served in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and for his service received a land grant near what is now Washington, Georgia.[4] He married Jane Cook, a woman of Scots-Irish descent whom he had met in South Carolina during his military service, in 1783.[5] Around 1793, Samuel and Jane moved to Kentucky.[6]

Jefferson F.[b] Davis was born at the family homestead in Davisburg, a village Samuel had established that later became Fairview, Kentucky, on June 3, 1808.[8][c]

Early education

In 1810, the Davis family moved to Bayou Teche. Less than a year later, they moved to a farm near Woodville, Mississippi, where Samuel began cultivating cotton and gradually increased the number of slaves he owned from six in 1810 to twelve.[11] He worked in the fields with his slaves, and eventually built a house, which Jane called Rosemont.[12] During the War of 1812, three of Davis's brothers served in the military.[13] When Davis was around five, he received a rudimentary education at a small schoolhouse near Woodville.[14] When he was about eight, his father sent him with Major Thomas Hinds and his relatives to attend Saint Thomas College, a Catholic preparatory school run by Dominicans near Springfield, Kentucky.[15] In 1818, Davis returned to Mississippi, where he briefly studied at Jefferson College in Washington. He then attended the Wilkinson County Academy near Woodville for five years.[16] In 1823, Davis attended Transylvania University in Lexington.[17] While he was still in college in 1824, he learned that his father Samuel had died. Before his death, Samuel had been in debt and had sold Rosemont and his slaves to his eldest son Joseph Emory Davis, who already owned a large plantation in Davis Bend, Mississippi.[18]

West Point and early military career

Joseph, who was 23 years older than Davis,[19] took on the role of being his surrogate father.[20] Joseph got Davis appointed to the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1824. He became friends with classmates Albert Sidney Johnston and Leonidas Polk.[21] During his time there, he frequently challenged the academy's discipline.[22] In his first year, he was court-martialed for drinking at a nearby tavern; he was found guilty but was pardoned.[23] The following year, Davis was placed under house arrest for his role in the Eggnog Riot during Christmas 1826, in which students defied the discipline of superintendent Sylvanus Thayer by getting drunk and disorderly, but was not dismissed.[24] He graduated 23rd in a class of 33.[25]

Following his graduation, Second Lieutenant Davis was assigned to the 1st Infantry Regiment. In early 1829, he was stationed at Forts Crawford and Winnebago in Michigan Territory under the command of Colonel Zachary Taylor,[26] later president of the United States. While serving in the military, Davis brought James Pemberton, an enslaved African-American that he had inherited from his father, with him as his personal servant.[27] The northern winters were unkind to Davis's health, and one winter he developed a bad case of pneumonia, after which he was vulnerable to catching colds and bronchitis.[28] Davis went to Mississippi on furlough in March 1832, missing the outbreak of the Black Hawk War. He returned to duty just before the Battle of Bad Axe, which ended the war.[29] After Black Hawk was captured, Davis escorted him for detention in St. Louis.[30] In his autobiography, Black Hawk stated that Jefferson treated him with kindness.[31]

After his return to Fort Crawford in January 1833, he and Taylor's daughter, Sarah, had become romantically involved. Davis asked Taylor if he could marry Sarah, but Taylor refused.[32] In spring, Taylor had him assigned to the United States Regiment of Dragoons under Colonel Henry Dodge. Davis was promoted to first lieutenant and deployed at Fort Gibson in Arkansas Territory.[33] In February 1835, he was court-martialed for insubordination.[34] Davis was acquitted, but in the meantime he had requested a furlough. Immediately after his furlough, he tendered his resignation, which was effective on June 30. He was twenty-six.[35]

Planting career and first marriage

When Davis returned to Mississippi he decided to become a planter.[36] His brother Joseph was successfully converting his large holdings at Davis Bend, about 15 miles (24 km) south of Vicksburg, Mississippi, into Hurricane Plantation, which eventually became 1,700 acres (690 ha) of cultivated fields and over 300 slaves.[37] He provided Davis 800 acres (320 ha) of his land to start a plantation at Davis Bend, though Joseph retained the title to the property. He also loaned Davis the money to buy ten slaves to clear and cultivate the land, which Jefferson named Brierfield Plantation.[38]

Davis had continued his correspondence with Sarah.[39] They agreed to marry, and Taylor gave his implicit assent. They married at Beechland on June 17, 1835.[40] In August, Davis and Sarah traveled south to Locust Grove Plantation, his sister Anna Smith's home in West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Within days, both became severely ill with malaria. Sarah died at the age of 21 on September 15, 1835, after only three months of marriage.[41]

For several years following Sarah's death, Davis spent much of his time at Brierfield supervising the enslaved workers and developing his plantation. By 1836, he possessed 23 slaves;[42] by 1840, he possessed 40;[43] and by 1860, 113.[44] He made his first slave, James Pemberton, Brierfield's effective overseer,[45] a position he held until his death around 1850.[44] Meanwhile, Davis also developed intellectually. Joseph maintained a large library on Hurricane Plantation, allowing Davis to read up on politics, the law, and economics.[46] Joseph, who became particularly concerned with national attempts to limit slavery in new territories during this time, often served as Davis's advisor as they increasingly became involved in politics,[47] and Jefferson was the beneficiary of his brother's political influence.[23]

Early political career and second marriage

Davis first became directly involved in politics in 1840 when he attended a Democratic Party meeting in Vicksburg and served as a delegate to the party's state convention in Jackson; he served again in 1842.[48] In November 1843, he was chosen to be the Democratic candidate for the state House of Representatives for Warren County less than one week before the election after the original candidate withdrew his nomination; Davis lost the election.[49]

In early 1844, Davis was chosen to serve as a delegate to the state convention again. On his way to Jackson, Davis met Varina Banks Howell, then 18 years old, when he delivered an invitation from Joseph for her to stay at the Hurricane Plantation for the Christmas season.[50] She was a granddaughter of New Jersey Governor Richard Howell; her mother's family was from the South.[51] At the convention, Davis was selected as one of Mississippi's six presidential electors for the 1844 presidential election.[52]

Within a month of their meeting, the 35-year-old Davis and Varina became engaged despite her parents' initial concerns about his age and politics.[53] For the remainder of the year, Davis campaigned for the Democratic party, advocating for the nomination of John C. Calhoun over Martin Van Buren who was the party's original choice. Davis preferred Calhoun because he championed southern interests including the annexation of Texas, reduction of tariffs, and building naval defenses in southern ports,[54] but he actively campaigned for James K. Polk when the party chose him as their presidential candidate.[55]

Davis and Varina married on February 26, 1845,[56] after the campaign ended.[57] They had six children: Samuel Emory, born in 1852, who died of an undiagnosed disease two years later;[58] Margaret Howell, born in 1855, who married, raised a family and lived to be 54;[59] Jefferson Davis, Jr., born in 1857, who died of yellow fever at age 21;[60] Joseph Evan, born 1859, who died from an accidental fall at age five;[61] William Howell, born 1864, who died of diphtheria at age 10;[62] and Varina Anne, born 1872, who remained single and lived to be 34.[63]

In July 1845, Davis became a candidate for the United States House of Representatives.[64] He ran on a platform that emphasized a strict constructionist view of the constitution, states' rights, a reduction of tariffs, and opposition to a national bank. He won the election and entered the 29th Congress.[65] He argued for the American right to annex Oregon but to do so by peaceful compromise with Britain.[66] Davis spoke against the use of federal monies for internal improvements that he believed would undermine the autonomy of the states,[67] and on May 11, 1846, he voted for war with Mexico.[68]

Mexican–American War

At the beginning of the Mexican–American War, Mississippi raised a volunteer unit, the First Mississippi Regiment, for the U.S. Army.[68] Davis expressed his interest in joining the regiment if elected its colonel, and in the second round of elections in June 1846 he was chosen.[69] He did not resign his position as a U.S. Representative, but left a letter of resignation with his brother Joseph to submit when he thought it was appropriate.[70]

Davis was able to get his entire regiment armed with new percussion rifles instead of the smoothbore muskets used by other regiments. President Polk had given his approval for their purchase as a political favor in return for Davis marshalling enough votes to pass the Walker Tariff,[71] despite the objections of the commanding general of the U.S. Forces, Winfield Scott, who felt that the guns had not been sufficiently tested and deplored the fact that they could not be fitted with bayonets.[72] Because of its association with the regiment, the rifle became known as the "Mississippi rifle",[73] and Davis's regiment became known as the "Mississippi Rifles".[74]

Davis's regiment was assigned to the army of his former father-in-law, Zachary Taylor, in northeastern Mexico. Davis distinguished himself at the Battle of Monterrey in September by leading a charge that took the fort of La Teneria.[75] He then went on a two-month leave and returned to Mississippi, where he learned that Joseph had submitted his resignation from the House of Representatives in October.[76] Davis returned to Mexico and fought in the Battle of Buena Vista on February 22, 1847. His tactics stopped a flanking attack by the Mexican forces that threatened to collapse the American line,[77] although he was wounded in the heel during the fighting.[78] In May, Polk offered Davis a federal commission as a brigadier general. Davis declined the appointment, arguing he could not directly command militia units because the U.S. Constitution gives the power of appointing militia officers to the states, not the federal government.[79] Instead, Davis accepted an appointment by Mississippi governor Albert G. Brown to fill the vacancy in the U.S. Senate[80] left when Jesse Speight died.[81]

Senator and Secretary of War

Senator

Davis took his seat in December 1847 and was appointed as a regent of the Smithsonian Institution.[82] The Mississippi legislature confirmed his appointment in January 1848.[83] He quickly established himself as an advocate of the South and its expansion into the territories of the West. He was against the Wilmot Proviso, which was intended to assure that any territory acquired from Mexico would be free of slavery. He asserted that only states, not territories, had sovereignty.[84] According to Davis, territories were the common property of the United States and Americans who owned slaves had as much right to move there with their slaves as other Americans. Davis tried to amend the Oregon Bill that established Oregon as a territory to allow settlers to bring their slaves.[85][86] Davis did not want to accept the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican–American War, claiming that Nicholas Trist, who negotiated the treaty, had done so as a private citizen and not a government representative;[87] he argued to have the treaty to cede additional land to the United States.[88]

During the 1848 presidential election, Davis did very little campaigning because he did not want to campaign against Zachary Taylor, who was the Whig candidate. The Senate session following Taylor's inauguration in 1849 only lasted until March 1849. Davis was able to return to Brierfield for seven months.[89] He was reelected by the state legislature for another six-year term in the Senate. During this time, he was approached by the Venezuelan adventurer Narciso López to lead a filibuster expedition to liberate Cuba from Spain. Davis turned down the offer, saying it was inconsistent with his duty as a senator.[90]

After the death of Calhoun in the spring of 1850, Davis became the senatorial spokesperson for the South.[91] During 1850, Congress debated the resolutions of Henry Clay. These resolutions aimed to address the sectional and territorial problems of the nation[92] and formed the basis for the Compromise of 1850.[93] Davis was against the resolutions, as he felt they would put the South at a political disadvantage.[94] For example, one of the first issues for discussion in early 1850 was the admission of California as a free state without its first becoming a territory. Davis countered that Congress should establish a territorial government for California, which would give Southerners the right to colonize the territory with their slaves. He suggested that extending the Missouri Compromise Line, which defined which territories were open to slavery, to the Pacific was acceptable,[95] arguing that the region south of the line was favorable for the expansion of slavery.[96] He stated that not allowing slavery into the new territories denied the political equality of Southerners,[97] and that it would destroy the balance of power between Northern and Southern states in the Senate.[98]

Davis continued to oppose the Compromise of 1850 after it passed.[99] In the autumn of 1851, he was nominated to run for governor of Mississippi on a states' rights platform against Henry Stuart Foote, who had favored the compromise. Davis accepted the nomination and resigned from the Senate. Foote won the election by a slim margin. Davis, who no longer held a political office, turned down reappointment to his seat by outgoing Governor James Whitfield.[100] He spent much of the next fifteen months at Brierfield.[101] He remained politically active, attending the Democratic convention in January 1852 and campaigning for Democratic candidates Franklin Pierce and William R. King during the presidential election of 1852.[102]

Secretary of War

In March 1853, President Franklin Pierce named Davis his Secretary of War.[103] Davis championed a transcontinental railroad to the Pacific, arguing it was needed for national defense,[104] and was entrusted with overseeing the Pacific Railroad Surveys to determine which of four possible routes was the best.[105] He promoted the Gadsden Purchase of today's southern Arizona from Mexico, partly because he preferred a southern route for the new railroad; the Pierce administration agreed and the land was purchased in December 1853.[106] Davis presented the surveys' findings in 1855, but they failed to clarify which route was best, and sectional problems arising with any attempt to choose one made constructing the railroad impossible at the time.[107] Davis also argued for the acquisition of Cuba from Spain, seeing it as an opportunity to add the island, a strategic military location, as another slave state to the Union.[108] He felt the size of the regular army was insufficient to fulfill its mission and that salaries had to be increased, something which had not occurred for 25 years. Congress agreed, adding four regiments, which increased the army's size from about 11,000 to about 15,000 soldiers, and raising its pay scale.[109] He ended the manufacture of smoothbore muskets for the military and shifted production to rifles, and worked to develop the tactics that go with them.[110] He oversaw the building of public works in Washington D.C., including federal buildings and the initial construction of the Washington Aqueduct.[111]

Davis helped get the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854 by allowing President Pierce to endorse it before it came up for a vote.[112] This bill, which created Kansas and Nebraska territories, explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise's limits on slavery and left the decision about a territory's slaveholding status to popular sovereignty, which allowed the territory's residents to decide.[113] The passage of this bill led to the demise of the Whig party, the rise of the Republican Party and civil violence in Kansas.[114] The Democratic nomination for the 1856 presidential election went to James Buchanan.[115] Knowing his term was over when the Pierce administration ended in 1857, Davis ran for Senate once more and re-entered it on March 4, 1857.[116] In the same month, the United States Supreme Court decided the Dred Scott case, which ruled that slavery could not be barred from any territory.[117]

Return to Senate

The Senate recessed in March and did not reconvene until November 1857.[118] The session opened with the Senate debating the Lecompton Constitution submitted by a convention in Kansas that would allow it to be admitted as a slave state. The issue divided the Democratic Party. Davis supported it, but it was not passed, in part because the leading Democrat in the North, Stephen Douglas, refused to support because he felt it did not represent the true will of the settlers in Kansas.[119] The controversy further undermined the alliance between northern and southern Democrats.[120]

Davis's participation in the Senate was interrupted by severe illness in early 1858. Davis, who regularly suffered from ill health,[121] had a recurring case of iritis, which threatened the loss of his left eye[122] and left him bedridden for seven weeks.[123] He spent the summer of 1858 in Portland, Maine. While recovering, he gave speeches in Maine, Boston, and New York, emphasizing the common heritage of all Americans and the importance of the constitution for defining the nation.[124] Because his speeches had angered some states' rights supporters in the South, Davis was required to clarify his comments when he returned to Mississippi. He stated that he felt positively about the benefits of Union, but acknowledged that the Union could be dissolved if states' rights were violated and one section of the country imposed its will on another.[125] Speaking to the Mississippi Legislature on November 16, 1858, Davis stated "if an Abolitionist be chosen President of the United States ... I should deem it your duty to provide for your safety outside of a Union with those who have already shown the will ...to deprive you of your birthright and to reduce you to worse than the colonial dependence of your fathers."[126]

In February 1860, Davis presented a series of resolutions defining the relationship between the states under the constitution, including the assertion that Americans had a constitutional right to bring slaves into territories.[127] These resolutions were seen as setting the agenda for the Democratic Party nomination,[128] ensuring that Douglas's idea of popular sovereignty, known as the Freeport Doctrine, would be excluded from the party platform.[129] At the Democratic convention, the party split: Douglas was nominated by the Northern half and Vice President John C. Breckinridge was nominated by the Southern half.[130] The Republican Party nominee Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 election.[131]

Davis counselled moderation,[132] but South Carolina adopted an ordinance of secession on December 20, 1860, and Mississippi did so on January 9, 1861. Davis had expected this but waited until he received official notification.[133] Calling January 21 "the saddest day of my life",[1] Davis delivered a farewell address to the United States Senate,[134] resigned, and returned to Mississippi.[135]

President of the Confederate States

Inauguration

Before his resignation, Davis had sent a telegraph to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus informing him that he was available to serve the state. On January 27, 1861, Pettus appointed him a major general of Mississippi's army.[136] On February 10, Davis learned that he had been unanimously elected to the provisional presidency of the Confederacy by a constitutional convention in Montgomery, Alabama,[137] which consisted of delegates from the six states that had seceded: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Alabama.[138] Davis was chosen because of his political prominence,[139] his military reputation,[140] and his moderate approach to secession,[139] which could bring Unionists and undecided voters over to his side.[141] Davis had been hoping for a military command,[142] but he accepted and committed himself fully to his new role.[143] Davis and Vice President Alexander H. Stephens were inaugurated on February 18.[144] The procession for the inauguration started at Montgomery's Exchange Hotel, the location of the Confederate administration and Davis's residence.[145]

Davis then formed his cabinet, choosing one member from each of the states of the Confederacy, including Texas which had recently seceded:[146] Robert Toombs of Georgia for Secretary of State, Christopher Memminger of South Carolina for Secretary of the Treasury, LeRoy Walker of Alabama for Secretary of War, John Reagan of Texas for Postmaster General, Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana for Attorney General, and Stephen Mallory of Florida for Secretary of the Navy. Davis stood in for Mississippi. The Confederate Congress quickly confirmed Davis's choices.[147] During his time as president, Davis's cabinet often changed; there were fourteen different appointees for the positions, including six secretaries of war.[148]

Civil War

As the Southern states seceded, state authorities had been able to take over most federal facilities without bloodshed. But four forts, including Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, had not surrendered. Davis preferred to avoid a crisis as he realized the Confederacy was still weak and needed time to organize its resources.[149] In February, the Confederate Congress advised Davis to send a commission to Washington to negotiate the settlement of all disagreements with the United States, including the evacuation of the forts. Davis did so and was willing to consider compensation,[150] but President of the United States Lincoln refused to meet with the commissioners. Instead, they informally negotiated with Secretary of State William Seward through an intermediary, Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell.[151] Seward hinted that Fort Sumter may be evacuated, but gave no assurance.[152]

In the meantime, Davis appointed Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina, to ensure that no assault was launched without his direct orders.[153] After being informed by Lincoln that he intended to resupply Fort Sumter with provisions, Davis convened with the Confederate Congress on April 8 and then gave orders to Beauregard to demand the immediate surrender of the fort or to reduce it. The commander of the fort, Major Robert Anderson, refused to surrender, and Beauregard began the attack on Fort Sumter early on April 12.[154] After over thirty hours of bombardment, the fort surrendered.[155] When Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion, four more states–Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas—joined the Confederacy. The American Civil War had begun.[156]

1861

In addition to being the constitutional commander-in-chief of the Confederacy, Davis was operational leader of the military, as the Confederacy's military departments reported directly to him.[158] Davis had a habit of overworking, particularly in minor military issues that could have been delegated.[159] Some of his colleagues—such as Generals Joseph E. Johnston and his friend from West Point,[160] Major General Leonidas Polk—encouraged him to lead the armies directly, but he let his generals direct the combat.[161]

The major fighting in the East began when a Union army advanced into Northern Virginia in July 1861.[162] It was defeated at Manassas by two Confederate forces commanded by Beauregard and Joseph Johnston.[163] After the battle, Davis had to manage disagreements with the two generals: Beauregard, who was now a full general, was upset because he felt he was not given sufficient credit for his ideas; Joseph Johnston was upset because he felt he was not given the seniority of rank due to him.[164]

In the West, Davis had to address another issue caused by one of his generals. Kentucky, which was leaning toward the Confederacy, had declared its neutrality. Polk decided to occupy Columbus, Kentucky, in September 1861, violating the state's neutrality.[165] Secretary of War Walker ordered him to withdraw. Davis initially agreed with Walker, but then changed his mind and allowed Polk to remain.[166] The violation of Kentucky's territory led it to request aid from the Union, effectively losing the state for the Confederacy.[167] Walker resigned as secretary of war and was replaced by Judah P. Benjamin.[168] Around this time, Davis appointed his long-time friend,[169] General Albert Sidney Johnston, as commander of the western military department that included much of Tennessee, Kentucky, western Mississippi, and Arkansas.[170]

1862

In February 1862, Union forces in the West captured Forts Henry and Donelson, including nearly half the troops in A. S. Johnston's department, which led to the collapse of the Confederate defenses. Within weeks, Kentucky, Nashville and Memphis were lost, [171] as well as control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.[172] The commanders responsible for the defeat were Brigadier Generals Gideon Pillow and John B. Floyd, political generals that Davis had been required to appoint.[173] Davis gathered troops defending the Gulf Coast and concentrated them with A. S. Johnston's remaining forces.[174] Davis favored using this concentration in an offensive.[175] Johnston attacked the Union forces at Shiloh in southwestern Tennessee on April 6. The attack failed, and Johnston was killed,[176] following which General Beauregard took command, first falling back to Corinth, Mississippi, and then to Tupelo, Mississippi.[177] Afterwards he put himself on leave, and in June, Davis put General Braxton Bragg in charge of the army.[178]

Around the time of the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson, Davis was inaugurated as president on February 22, 1862. In his inaugural speech,[179] he admitted that the South had suffered disasters, but called on the people of the Confederacy to renew their commitment.[180] He replaced Secretary of War Benjamin, who had been scapegoated for the defeats, with George W. Randolph, although he subsequently made Benjamin secretary of state to replace Hunter, who had stepped down.[181] Davis vetoed a bill to create a commander in chief for the army in March 1862, but he did select General Robert E. Lee to be his military advisor.[182] They formed a close relationship,[183] and Davis relied on Lee for counsel until the end of the war.[184]

In the East, Union troops began an amphibious attack in March 1862 on the Virginia Peninsula, 75 miles from Richmond.[185] Davis and Lee wanted Joseph Johnston, who commanded the Confederate army near Richmond, to make a stand at Yorktown.[186] Instead, Johnston withdrew from the peninsula without informing Davis.[187] Davis reminded Johnston that it was his duty to not let Richmond fall.[188] On May 31, 1862, Johnston engaged the Union army less than ten miles from Richmond at the Battle of Seven Pines, and he was wounded.[189] Davis then put Lee in command. Lee began the Seven Days Battles less than a month later, pushing the Union forces back down the Virginia Peninsula[190] and eventually forcing them to withdraw from Virginia.[191] Lee beat back another army moving into Virginia at the Battle of Second Manassas in August 1862. Davis expressed his full confidence in Lee. Knowing Davis desired an offensive into the North, Lee invaded Maryland on his own initiative,[192] but retreated back to Virginia after a bloody stalemate at Antietam in September.[193] In December, Lee stopped another invasion of Virginia at the Battle of Fredericksburg.[194]

In the West, Bragg shifted most of his available forces from Tupelo to Chattanooga in July 1862 for an offensive toward Kentucky.[195] Davis approved, suggesting that an attack could gain the Confederacy Kentucky and regain Tennessee,[196] but he did not create a unified command.[197] He had created a new department independent of Bragg under Major General Edmund Kirby Smith at Knoxville, Tennessee, assuming that Bragg and Kirby Smith would work together.[198] In August, both armies invaded Kentucky. Frankfort was briefly captured and a Confederate governor was inaugurated, but the attack collapsed, in part due to lack of coordination between the two generals. After a stalemate at the Battle of Perryville,[199] Bragg and Kirby Smith retreated to Tennessee. In December, Bragg was defeated at the Battle of Stones River.[200] In the meantime, Confederate positions along the Mississippi near Vicksburg remained relatively secure.[201]

In response to the defeat and the lack of coordination, Davis reorganized the command in the West in November, combining the armies in Tennessee and Vicksburg into a department under the overall command of Joseph Johnston.[202] Davis expected Johnston to relieve Bragg of his command because of his defeats, but Johnston refused.[203] During this time, Secretary of War Randolph resigned because he felt Davis refused to give him the autonomy to do his job; Davis replaced him with James Seddon.[204]

In the winter of 1862, Davis was attending the Episcopal Church; in May 1863, he was confirmed at St. Paul's Episcopal Church.[205]

1863

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Davis saw this as evidence of the North's desire to destroy the South and as inciting the enslaved people of the South to rebellion.[206] In his opening address to Congress on January 12,[207] he declared the proclamation "the most execrable measure recorded in the history of guilty man". Davis requested a law that Union officers captured in Confederate states be delivered to state authorities to be tried and executed for inciting slave rebellion.[208] In response, the Congress passed a law that Union officers of United States Colored Troops could be put on trial and executed upon conviction, and that captured black soldiers would be turned over to the states they were captured in to be dealt with as the state saw fit. Nevertheless, no Union officers were executed under the law.[209]

In May, Lee broke up another invasion of Virginia at the Battle of Chancellorsville,[210] and countered with an invasion into Pennsylvania. Davis approved, thinking that a victory in Union territory could gain recognition of Confederate independence,[211] but Lee's army was defeated at the Battle of Gettysburg in July.[212] After retreating to Virginia, Lee was able to block any major Union offensives into the state.[213]

In April, the Union forces under Grant resumed their attack on Vicksburg.[214] Davis concentrated troops from across the south to counter the move,[215] but Joseph Johnston did not stop the Union forces.[216] Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton withdrew his army into Vicksburg, and after a siege, surrendered on July 4. The loss of Vicksburg and of Port Hudson, Louisiana, led to Union control of the Mississippi. Davis relieved Johnston of his department command.[217] During the summer, Bragg's army was maneuvered out of Chattanooga and had fallen back to Georgia.[218] In September, Bragg attacked the Union army at the Battle of Chickamauga and forced it to retreat to Chattanooga, which he then put under siege.[219] After the battle, Davis visited Bragg's army to settle ongoing problems with his command. Davis acknowledged that Bragg did not have the confidence of his immediate subordinates, but decided to keep him in command.[220] In mid-November, the Union army counterattacked and Bragg's forces retreated to northern Georgia,[221] following which Bragg resigned his command. Davis replaced him with Joseph Johnston,[222] and assigned Bragg as an informal chief of staff.[223]

Davis also had problems in Richmond. During 1863, the Confederate people were starting to suffer from food shortages and rapid price inflation, particularly in cities that depended on shipments from a transportation system that was breaking down. These resulted in what were known as the bread riots.[224] During one riot in Richmond in April, a mob protesting food shortages broke into shops. After the mayor of Richmond had called the militia, Davis arrived, stood on a wagon, and promised the mob he would get food and reminded them of their patriotic duty. He then ordered them to disperse or he would command the soldiers to open fire. The crowd dispersed.[225] In October, Davis went on a month-long journey around the South to give speeches, meet with political and military leaders, and rally the citizenry.[226]

1864–1865

Addressing the Second Confederate Congress on May 2, 1864,[227] Davis outlined his strategy of achieving Confederate independence by outlasting the Union will to fight.[228] The speech stated that the Confederates would continue to show the Union they could not be subjugated and hoped to convince the North to vote in a president open to making peace.[229]

Near the beginning of 1864, Davis encouraged Joseph Johnston to begin active operations in Tennessee, but Johnston refused.[230] In May, the Union armies began advancing toward Johnston's army, which repeatedly retreated toward Atlanta, Georgia. In July, Davis replaced Johnston with General John B. Hood,[231] who immediately engaged the Union forces in a series of battles around Atlanta. The battles did not succeed in stopping the Union army and Hood abandoned the city on September 2. The victory raised Northern morale and assured Lincoln's reelection.[232] The Union forces then marched to Savannah, Georgia, capturing it in December, then advanced into South Carolina, forcing the Confederates to evacuate Charleston.[233] In the meantime, Hood advanced north and was repulsed in a drive toward Nashville in December 1864.[234]

In Virginia, Union forces began a new advance into Northern Virginia. Lee put up a strong defense and they were unable to directly advance on Richmond, but managed to cross the James River. In June 1864, Lee fought the Union armies to a standstill; both sides settled into trench warfare around Petersburg, which would continue for nine months.[235]

In January, the Confederate Congress passed a resolution making Lee general-in-chief, and Davis signed it in February.[236] Seddon resigned as Secretary of War and was replaced by John C. Breckinridge, who had run for president in 1860. During this time, Davis sent envoys to Hampton Roads for peace talks, but Lincoln refused to consider any offer that included an independent Confederacy.[237] Davis also sent Duncan F. Kenner, the chief Confederate diplomat, on a mission to Great Britain and France, offering to gradually emancipate the enslaved people of the south for political recognition.[238] In March, Davis convinced Congress to sign a bill allowing the recruitment of African-Americans in exchange for their freedom.[239]

End of the Confederacy and capture

At the end of March, the Union army broke through the Confederate trench lines, forcing Lee to withdraw and abandon Richmond.[240] Davis intended to stay as long as possible, but evacuated his family, which included Jim Limber, a free black orphan they briefly adopted, from Richmond on March 29.[241] On April 2, Davis and his cabinet escaped by rail to Danville, Virginia, where William T. Sutherlin's mansion served as the seat of Government.[242] Davis issued a proclamation on April 4,[243] encouraging the people of the Confederacy to continue resistance.[244] Pursued by Union forces, Lee surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9.[240] After unofficially hearing of Lee's surrender, the president and his cabinet headed to Greensboro, North Carolina, hoping to join Joseph Johnston's army.[244]

In Greensboro, Davis held a summit with his cabinet, Joseph Johnston, Beauregard, and Governor Zebulon Vance of North Carolina, arguing that they must cross the Mississippi River and continue the war there. The generals argued that they did not have the forces to continue; Davis finally gave Johnston authorization to discuss terms of capitulation for his army.[245] Davis continued south, hoping to continue the fight.[246] When Lincoln was assassinated on April 14, the Union government implicated Davis, and a bounty of $100,000 (equivalent to $3,600,000 in 2023) was put on his head.[247] On May 2, Davis met with Secretary of War Breckinridge and Bragg in Abbeville, Georgia, to see if they could pull together an army to continue the fight. He was told that they were not able to. On May 5, Davis met with his cabinet in Washington, Georgia, and officially dissolved the Confederate government.[248] Davis continued on, hoping to join Kirby Smith's army across the Mississippi.[244] Davis was finally captured on May 9 near Irwinville, Georgia, when Union soldiers found his encampment. He tried to evade capture, but was caught wearing a loose-sleeved, water-repellent cloak and a black shawl over his head,[249] which gave rise to depictions of him in political cartoons fleeing in women's clothes.[250]

Civil War policies

National policy

Davis's central concern during the war was to achieve Confederate independence.[252] When Virginia seceded, the state convention offered Richmond as the Confederacy's capital and the provisional Confederate Congress accepted it. Davis favored the move.[253] Richmond was a larger city, had better transportation links than Montgomery, and was home to the Tredegar Iron Works, one of the largest foundries in the world. It ensured Virginia's support for the war,[254] and it was associated with the revolutionary generation of leaders, such as George Washington,[255] Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison.[253] Davis arrived in Richmond at the end of May 1861,[256] moving into the White House of the Confederacy in August.[257] In November, Davis was officially elected to a six-year term, and was inaugurated on February 22, 1862.[258] On his arrival in Richmond, Davis had attempted to create public support for the war by describing it as a battle for liberty,[259] claiming the original U.S. Constitution as the sacred document of the Confederacy.[260] He deemphasized the role slavery played in the secession,[259] but asserted white citizens' right to have slaves without outside interference.[261]

Davis had to create a government with almost no institutional structures in place.[262] At the beginning of the war, the Confederacy had no army, treasury, diplomatic missions, or bureaucracy.[263] Davis quickly built a strong central government to address these problems. For instance, he created a Bureau of Ordnance and convinced Josiah Gorgas to be its head.[264] Gorgas successfully built an arms industry from the ground up,[265] creating a network of government-supervised factories for war materials[266] and using innovative measures to produce a stable supply of gunpowder.[267]

Though he supported states' rights, Davis believed the constitution gave him the right to centralize authority to prosecute the war. Learning that the Confederacy's military facilities were controlled by the individual states, he worked with the Congress to bring them under national authority.[268] He received authorization from Congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus when needed.[269] Contrary to the desires of state governors who wanted their troops available for local defense, he intended to deploy military forces based on national need and was authorized to create a centralized army that could enlist volunteers directly.[270] When the soldiers in the volunteer army seemed unwilling to re-enlist in 1862, Davis instituted the first conscription in American history.[271] He also challenged property rights. In 1864, he recommended a direct 5% tax on all property, both land and slaves,[272] and implemented the impressment of supplies and slave labor for the military effort.[273] These policies made him unpopular with states' rights advocates and state governors, who saw him as creating the same kind of government they had seceded from.[274] In 1865, Davis's commitment to independence led him to compromise on slavery; he convinced Congress to pass a law that allowed African-Americans to earn their freedom by serving in the military, though it came too late to have an effect on the war.[275]

Foreign policy

The main objective of Davis's foreign policy was to achieve foreign recognition,[276] allowing the Confederacy to secure international loans, receive foreign aid to open trade,[277] and provide the possibility of a military alliance. Diplomacy was primarily focused on getting recognition from Britain.[278] Davis was confident that Britain's and most other European nations' economic dependence on cotton from the South would quickly convince them to sign treaties with the Confederacy.[279] Cotton had made up 61% of the value of all U.S. exports. The South filled most of the European cloth industry's need for cheap imported raw cotton: 77% of Britain's, 90% of France's, 60% of the German states', and 92% of Russia's. Around 20% of British workers were employed in the industry and half of British exports were finished cotton goods.[280] Despite Britain's imperative need for cotton, the Confederacy was prepared to downplay the role of slavery as the British Empire had outlawed it in 1833.[278] One of Davis's first choices for envoy to Britain, William Yancey, was a poor one.[281] He was a strong defender of slavery and had favored the return of the slave trade, creating the impression that he was impulsive and erratic.[282] British opinion did not turn against the South in the first year of the war, but that was because the Union had initially failed to declare that abolition was a war goal.[283]

There was no Southern consensus on how to use cotton to gain European support. Davis wanted to make the cotton available, but require the Europeans to obtain it by violating the blockade declared by the Union; Secretary of War Benjamin and Secretary of the Treasury Memminger wanted to export cotton to Europe and warehouse it there to use as credit; the majority of Congress wanted to embargo cotton until Europe was coerced to help the South.[284] Davis did not allow an outright embargo; he thought it might push Britain and France away. This stance gave him a chance to be an proponent of open trade,[285] but an embargo was effectively put into place anyway.[286] In May 1861, Britain declared neutrality, recognizing the Confederacy as a belligerent who could buy arms but not as a nation that could make treaties.[287] In midsummer, Britain agreed to honor the Union's blockade.[288] By 1862, the price of cotton in Europe had quadrupled and European imports of cotton from the United States were down 96%,[289] but instead of joining with the Confederacy, European cotton manufacturers found new sources, such as India, Egypt and Brazil.[290]

British intervention on the side of the Confederacy remained possible for a short while after Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which many in Britain initially saw as a desperate political gesture[291] that risked causing a race war by sparking a slave rebellion.[292] Davis's view of the proclamation was similar,[293] but the Confederates needed to achieve decisive victories to demonstrate their independence before the British would consider being involved.[294] Over time, the proclamation undermined foreign support for the South as no slave rebellion occurred and it became apparent that the Union aimed to end slavery.[295] By the end of the war, not a single foreign nation had recognized the Confederate States of America.[296]

Financial policy

Although Davis thought the war might be a long one, he did not propose legislation or take executive action to create the needed financial structure for the Confederacy. Davis knew very little about public finance, largely deferring to Secretary of the Treasury Memminger.[297] Memminger's knowledge of economics was limited, and he was ineffective at getting Congress to listen to his suggestions.[298] Until 1863, Davis's reports on the financial state of the Confederacy to Congress tended to be unduly optimistic;[299] for instance, in 1862 he stated that the government bonds were in good shape and debt was low in proportion to expenditures.[300]

Initially, the Confederacy raised money through loans. The first loans were bought by local and state banks using specie.[301] This money was supplemented by money confiscated from U.S. mints, depositories and custom houses.[302] Much of this specie was used to buy military goods in Europe.[303] In 1861, Memminger initiated "produce loans" that could be purchased with goods like cotton or tobacco.[304] Though the government could not sell much of the produce due to the blockade, it did provide the government with collateral for foreign loans.[305] The most important of these loans was the Erlanger loan in 1862,[306] which gave the Confederacy the specie needed to continue buying war material from Europe throughout 1863 and 1864.[307]

Davis's failure to argue for needed financial reform allowed Congress to avoid unpopular economic measures,[299] such as taxing planters' property[308]—both land and slaves—that made up two-thirds of the South's wealth.[300] At first the government thought it could raise money with a low export tax on cotton,[309] but the blockade prevented this. Though the provisional Congress levied a war tax of one-half percent on all property, including slaves, the government lacked the apparatus to efficiently collect it. The adoption of the Confederate Constitution prohibited further direct taxation on property.[310] Instead, the Confederate government relied on printing treasury notes. By the end of 1863, the currency in circulation was three times more than needed by the economy,[300] leading to inflation and sometimes refusal to accept the notes.[311] In his opening address to the fourth session of Congress in December 1863,[312] Davis demanded the Congress pass a direct tax on property despite the constitution.[313] Congress complied, but the tax had too many loopholes and exceptions,[314] and failed to produce the needed revenue.[315] Throughout the existence of the Confederacy, taxes accounted for only one-fourteenth of the government's income;[316] consequently, the government used the printing press to fund the war, thus destroying the value of the Confederate currency.[317] By the end of the war, the government was relying on impressments to fill the gaps created by lack of finances.[318]

Imprisonment

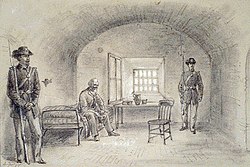

On May 22, Davis was imprisoned in Fort Monroe, Virginia, under the watch of Major General Nelson A. Miles. Initially, he was confined to a casemate, forced to wear fetters on his ankles, required to have guards constantly in his room, forbidden contact with his family, and given only a Bible and his prayerbook to read.[319] Over time, his treatment improved: due to public outcry, the fetters were removed after five days; within two months, the guard was removed from his room, he was allowed to walk outside for exercise, and he was allowed to read newspapers and other books.[320] In October, he was moved to better quarters.[321] In April 1866, Varina was permitted to regularly visit him. In September, Miles was replaced by Brevet Brigadier General Henry S. Burton, who permitted Davis to live with Varina in a four-room apartment.[322] In December, Pope Pius IX sent a photograph of himself to Davis.[323][f]

President Andrew Johnson's cabinet was unsure what to do with Davis. They considered trying him by military court for war crimes—his alleged involvement in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln or the mistreatment of Union prisoners of war at Andersonville Prison— but could not find any reliable evidence directly linking Davis to either. In late summer 1865, Attorney General James Speed determined that it was best to try Davis for treason in a civil trial.[324] In June 1866, the House of Representatives passed a resolution by a vote of 105 to 19 to put Davis on trial for treason.[325] Davis also wanted a trial to vindicate his actions,[326] and his defense lawyer, Charles O'Conor, realized a trial could be used to test the constitutionality of secession by arguing that Davis did not commit treason because he was no longer a citizen of the United States when Mississippi left the United States.[327] This created a dilemma for the Johnson administration. The trial was to be set in Richmond, which might be sympathetic to Davis, and an acquittal could be interpreted as validating the legality of secession.[328]

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released at Richmond on May 13, 1867, on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith.[329] Davis and Varina went to Montreal, Quebec, to join their children who had been sent there while he was in prison, and they moved to Lennoxville, Quebec.[330] Davis remained under indictment until after Johnson's proclamation on Christmas 1868 granting amnesty and pardon to all participants in the rebellion.[331] In February 1869, Attorney General William Evarts informed the court that the federal government declared it was no longer prosecuting the charges against him.[332] Though Davis's case never went to trial, his incarceration made him a martyr for many white southerners.[333]

Later years

Seeking a livelihood

Despite his financial situation, after his prison release, Davis refused work that he perceived as diminishing his status as a former senator and president.[334] He turned down a position as head of Randolph–Macon College in Virginia because he did not want to damage the school's reputation while he was under indictment.[335] In the summer of 1869, he traveled to Britain and France seeking business opportunities, but failed to find any.[336] After the federal government dropped its case against him,[337] Davis returned to the U.S. in October 1870 to become president of the Carolina Life Insurance Company in Tennessee. Leaving his family in England, he lived in a hotel and committed himself to work, hiring former friends to serve as agents. Shortly afterwards, he was offered the top post at the University of the South, which he declined because of the salary.[338]

After he retrieved his family from England in 1870, Davis received invitations to speak.[339] He avoided politics in his 1870 eulogy to Robert E. Lee at the Lee Monument Association in Richmond, emphasizing Lee's character instead.[340] He declined most opportunities, but gave the 1871 commencement speech at the University of the South.[341] He declared in a speech to the Virginia Historical Society that the South had been cheated, and would not have surrendered if they had known what to expect from Reconstruction,[341] particularly the changed status of freed African Americans.[342] After the Panic of 1873 severely affected the Carolina Life Company, Davis resigned in August 1873 when the directors merged the company over his objections.[343] He returned to England in 1874 looking to convince an English insurance company to open a branch in the American South, but heard that animosity toward him in the North was too much of a liability. He explored other employment possibilities in France, but none worked out.[344]

Around this time, Davis took action to reclaim Brierfield.[345] After the war, Davis Bend had been taken over by the Freedmen's Bureau which employed former enslaved African Americans as laborers. Joseph had successfully applied for a pardon and was able to regain ownership of his land, including both Hurricane and Brierfield plantations.[346] Unable to maintain the property, Joseph sold it to his former slave Ben Montgomery and his sons, Isaiah and William.[347] When Joseph died in 1870, he made Davis one of his will's executors, but his will did not specifically deed the land to Davis. Davis litigated to gain control of Brierfield,[348] and when a judge dismissed his suit in 1876, he appealed. In 1878, the Mississippi supreme court found in his favor. He then foreclosed on the Montgomerys who were in default on their mortgage and in December 1881, Brierfield was back in his hands,[349] although he did not live there and it did not produce a reliable income.[350]

After returning from Europe in 1874, Davis continued to explore ways to make a living, including investments in railroads and mining in Arkansas and Texas,[345] and in building an ice-making machine. He gave a few speeches at county fairs as well.[341] In 1876, the Agriculture and Mechanical College of Texas offered him the presidency, but he turned it down because Varina did not want to live in Texas.[351] He also worked for an English company, the Mississippi Valley Society, to promote trade and European immigration. Davis traveled through the South and Midwest, and in 1876, he and Varina again went to Europe. After determining that the business was not succeeding, he returned to the United States while Varina stayed in England.[352]

Author

In January 1877, the author Sarah Dorsey invited him to live on her estate at Beauvoir, Mississippi, and to begin writing his memoirs. He agreed, but insisted on paying board.[353] Davis's desire to write a book showing the righteousness of his cause had begun taking tangible form in 1875, when he authorized William T. Walthall, a former Confederate officer and Carolina Life agent, to find a publisher. Walthall worked out a contract with D. Appleton & Company, in which Walthall got a monthly stipend for preparing the work for publication and Davis received the royalties when the book was completed. The deadline for the contract was July 1878.[353] As he worked on his book, Davis occasionally agreed to speaking engagements. In his speeches, which were to veterans of the Mexican–American War or Confederate veterans, he defended the right of secession, attacked Reconstruction, and promoted national reconciliation.[341]

When Davis began writing at Beauvoir, he and Varina lived separately. When Varina came back to the United States, she initially refused to come to Beauvoir because she did not like Davis's close relationship with Dorsey, who was serving as his amanuensis. In the summer of 1878, Varina relented, moving to Beauvoir and taking over the role of Davis's assistant.[354] Dorsey died in July 1879, and left Beauvoir to Davis in her will, providing him with a permanent home.[355] In 1878, Davis missed the deadline to complete his work, and eventually Appleton intervened directly. Walthall was dismissed and the company hired William J. Tenney, who was experienced with getting manuscripts into publishable condition. In 1881, Davis and Tenney were able to publish the two volumes of The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.[356] The book was intended as a vindication of Davis's actions, reiterating that the South had acted constitutionally in seceding from the Union and that the North was wrong for prosecuting an unjust, destructive war; additionally it explicitly downplayed slavery's role in the origins of the war.[357]

In the 1870s, Davis became a life-time member of the Southern Historical Society.[358] The society was devoted to presenting the Lost Cause explanation of the Civil War[359]. Initially, the society had scapegoated political leaders like Davis for losing the war,[360] but eventually shifted the blame for defeat to the former Confederate general James Longstreet.[361] Davis avoided public disputes regarding blame, but he did personally reply to Theodore Roosevelt, who accused him of being a traitor like Benedict Arnold. Davis publicly maintained that he had done nothing wrong and had always upheld the Constitution.[362]

Davis spent most of his final years at Beauvoir.[355] In 1886, Henry W. Grady, an advocate for the New South, convinced Davis to lay the cornerstone for a monument to the Confederate dead in Montgomery, Alabama, and to attend the unveilings of statues memorializing Davis's friend Benjamin H. Hill in Savannah and the Revolutionary War hero Nathanael Greene in Atlanta.[363] The tour was a triumph for Davis and got extensive newspaper coverage, which emphasized national unity and the South's role as a permanent part of the United States. At each city and on stops along the way, large crowds came out to cheer Davis, solidifying his image as an icon of the Old South and the Confederate cause, and making him into a symbol for the New South.[364] In October 1887, Davis participated in his last tour, traveling to the Georgia State Fair in Macon, Georgia, for a grand reunion with Confederate veterans. He also continued writing. In the summer of 1888, he was encouraged by James Redpath, editor of the North American Review, to write a series of articles.[365] Redpath's encouragement also helped Davis to completed his final book A Short History of the Confederate States of America in October 1889;[366] he also began dictating his memoirs, although they were never finished.[367]

Death

In November 1889, Davis embarked on a steamboat in New Orleans in a cold rain, intending to visit his Brierfield plantation. He fell ill during the trip, but refused to send for a doctor, and an employee telegrammed Varina, who took a steamer to meet his vessel. Davis was diagnosed with acute bronchitis complicated by malaria.[368] When he returned to New Orleans, Davis's doctor Stanford E. Chaille pronounced him too ill to travel. He was taken to the home of Charles Erasmus Fenner, the son-in-law of his friend J. M. Payne, where he was bedridden but stable for two weeks. He took a turn for the worse and died at 12:45 a.m. on Friday, December 6, 1889, in the presence of several friends and holding Varina's hand.[369]

Funeral and reburial

Davis's body lay in state at the New Orleans City Hall from December 7 to 11. During this period the prominence of the United States flag emphasized Davis's relationship to the United States, but the hall was decorated by crossed U.S. and Confederate flags.[370] Davis's funeral was one of the largest held in the South; over 200,000 mourners were estimated to have attended. During the funeral his coffin was draped with a Confederate flag and his sword from the Mexican-American War.[371] The coffin was transported on a two-mile journey to the cemetery in a modified, four-wheeled caisson to emphasize his role as a military hero. The ceremony was brief; a eulogy was pronounced by Bishop John Nicholas Galleher, and the funeral service was that of the Episcopal Church.[372]

After Davis's funeral, various Southern states requested to be the final resting site for Davis's remains.[371] Varina decided that Davis should be buried in Richmond, which she saw as the appropriate resting place for dead Confederate heroes.[373] She chose Hollywood Cemetery. In May 1893, Davis's remains traveled from New Orleans to Richmond. Along the way, the train stopped at various cities, receiving military honors and visits from governors, and the coffin was allowed to lie in state in three state capitols: Montgomery, Alabama; Atlanta, Georgia; and Raleigh, North Carolina.[374] After Davis was reburied, his children were reinterred on the site as Varina requested,[375] and when Varina died in 1906, she too was buried beside him.[376]

Political views on slavery

During his years as a senator, Davis was an advocate for the Southern states' right to slavery. In his 1848 speech on the Oregon Bill,[377] Davis argued for a strict constructionist understanding of the Constitution. He insisted that the states are sovereign, all powers of the federal government are granted by those states,[378] the Constitution recognized the right of states to allow citizens to have slaves as property, and the federal government was obligated to defend encroachments upon this right.[379] In his February 13–14, 1850, speech on slavery in the territories,[380] Davis declared that slaveholders must be allowed to bring their slaves in, arguing that this does not increase slavery but diffuses it.[381] He further claimed that slavery does not need to be justified: it was sanctioned by religion and history,[382] blacks were destined for bondage,[383] their enslavement was a civilizing blessing to them[384] that brought economic and social good to everyone.[385] He explained the growth of abolitionism in the north as a symptom of a growing desire to destroy the South and the foundations of the country: "fanaticism and ignorance–political rivalry–sectional hate–strife for sectional dominion, have accumulated into a mighty flood, and pour their turgid waters through the broken Constitution".[386] On February 2, 1860,[387] Davis presented a set of resolutions to the Senate that not only reaffirmed the constitutional rights of slave owners, but also declared that the federal government should be responsible for protecting slave owners and their slaves in the territories.[388]

After secession and during the Civil War, Davis's speeches acknowledged the relationship between the Confederacy and slavery. In his resignation speech to the U. S. Senate, delivered 12 days after his state seceded, Davis said Mississippi "has heard proclaimed the theory that all men are created free and equal, and this made the basis of an attack upon her social institutions and the sacred Declaration of Independence has been invoked to maintain the position of the equality of the races."[134] In his February 1861 inaugural speech as provisional president of the Confederacy,[389] Davis asserted that the Confederate Constitution, which explicitly prevented Congress from passing any law affecting African American slavery and mandated its protection in all Confederate territories, as a return to the intent of the original founders.[390] When he spoke to Congress in April on the ratification of the Constitution,[391] he stated that the war was caused by Northerners whose desire to end slavery would destroy Southern property worth millions of dollars.[392] In his 1863 address to the Confederate Congress,[207] Davis denounced the Emancipation Proclamation as evidence of the North's long-standing intention to destroy slavery[393] and dooming African Americans, who he described as belonging to an inferior race, to extermination.[394] In early 1864, Major General Patrick Cleburne sent a proposal to Davis to enlist African Americans in the army, but Davis silenced it.[395] Near the end of the year, Davis changed his mind and endorsed the idea. Congress passed an act supporting him, but left the principle of slavery intact by leaving it to the states and individual owners to decide which slaves could used for military service,[396] and Davis's administration accepted only African Americans who had been freed by their masters as a condition of their being enlisted.[397]

In the years following the war, Davis joined other Lost Cause proponents and downplayed slavery as a cause of the war.[398] In The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government,[399] he wrote that slavery played only an incidental role in the Civil War,[400] and that it did not cause the conflict.[401]

Performance as commander in chief

Davis came to the role of commander in chief with military experience. He had graduated from West Point Military Academy, had regular army and combat experience, and commanded both volunteer and regular troops.[402] He was confident of his military abilities.[403] Davis played an active role in overseeing the military policy of the Confederacy: he worked long hours attending to paperwork related to the organization, finance, and logistics needed to maintain the Confederate armies.[404]

Some historians argued that aspects of Davis's personality contributed to the defeat of the Confederacy.[405] His focus on military details has been used as an example of his inability to delegate,[406] which led him to lose focus on larger issues.[407] He has been accused of being a poor judge of generals:[408] appointing people—such as Bragg, Pemberton, and Hood—–who failed to meet expectations,[409] overly trusting long-time friends,[410] and retaining generals, like Joseph Johnston, long after they should have been removed.[411] Davis's need to be seen as always in the right has also been described as a problem.[412] Historians have argued that the time spent vindicating himself took time away from larger issues and accomplished little,[413] his reactions to criticism created many unnecessary enemies,[414] and the hostile relationships he had with politicians and generals he depended on, particularly Beauregard and Joseph Johnston, impaired his ability as commander in chief.[415] It has also been argued that his focus on military victory at all costs undermined the values the South was fighting for, such as states' rights[416] and slavery,[417] but provided no alternatives to replace them.[418]

Other historians have pointed out his strengths. In particular, despite the South's focus on states' rights, Davis quickly mobilized the Confederacy and stayed focused on gaining independence.[419] He was a skilled orator who attempted to share the vision of national unity.[420] He shared his message through newspaper, public speeches, and trips where he would meet with the public.[421] Davis's policies sustained the Confederate armies through numerous campaigns, buoying Southern hopes for victory and undermining the North's will to continue the war.[422] A few historians have argued that Jefferson may have been one of the best people available to serve as commander in chief. Though he was unable to win the war,[423] he rose to the challenge of the presidency,[424] pursuing a strategy that not only enabled the Confederacy to hold out as long as it did, but almost achieved its independence.[425]

Legacy

Although Davis served the United States as a soldier and a war hero, a politician who sat in both houses of Congress, and an effective cabinet officer,[426] his legacy is mainly defined by his role as president of the Confederacy.[427] After the Civil War, journalist Edward A. Pollard, who first popularized the Lost Cause mythology,[428] placed much of the blame for losing the war on Davis.[429] Into the twentieth century, many biographers and historians have agreed with Pollard, emphasizing Davis's responsibility for the South's failure to achieve independence.[430] In the second half of the twentieth century, some scholars argued that he was a capable leader, but his skills were insufficient to overcome the challenges the Confederacy faced.[431] Historians writing in the twenty-first century also acknowledge his abilities, while exploring how his limitations may have contributed to the war's outcome.[432]

Davis's standing among white Southerners was at a low point at the end of the Civil War,[433] but it rebounded after his release from prison.[434] After Reconstruction, he became a venerated figure of the white South,[435] and he was praised for having suffered on its behalf.[436] Davis's later writings helped popularize Lost Cause mythology,[437] contending that the South was in the right when it seceded, the Civil war was not about slavery,[438] the Union was victorious because of its overwhelming numbers,[439] and Longstreet's actions at Gettysburg prevented the Confederacy from winning.[440] His birthday was made a legal holiday in six southern states.[441] His popularity among white Southerners remained strong in the early twentieth century. Around 200,000 people attended the unveiling of the Jefferson Davis Memorial at Richmond, Virginia, in 1907.[442] In 1961, a centennial celebration reenacted Davis's inauguration in Montgomery, Alabama, with fireworks and a cast of thousands in period costumes.[443] In the early twenty-first century, there were at least 144 Confederate memorials commemorating him throughout the United States.[444]