History of wine: Difference between revisions

m clean up, References after punctuation per WP:REFPUNC and WP:CITEFOOT using AWB (8792) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

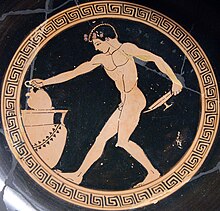

[[File:Banquet Louvre G133.jpg|thumb|Wine boy at a Greek [[symposium]]]] |

[[File:Banquet Louvre G133.jpg|thumb|Wine boy at a Greek [[symposium]]]] |

||

The history of [[wine]] spans thousands of years and is closely intertwined with the history of [[agriculture]], [[cuisine]], [[civilization]] and [[History of the world|humanity]] itself. Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest known wine production occurred in what is now the country of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]] around 7000 |

The history of [[wine]] spans thousands of years and is closely intertwined with the history of [[agriculture]], [[cuisine]], [[civilization]] and [[History of the world|humanity]] itself. Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest known wine production occurred in what is now the country of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]] around 7000 BC,<ref name=independent8k>{{cite news |first=David |last=Keys |title=Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine |url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/now-thats-what-you-call-a-real-vintage-professor-unearths-8000yearold-wine-577863.html |work=[[The Independent]] |date=2003-12-28 |accessdate=2011-03-20}}</ref><ref name=archaeology96>{{cite journal |first=Mark |last=Berkowitz |title=World's Earliest Wine |url=http://www.archaeology.org/9609/newsbriefs/wine.html |publisher=Archaeological Institute of America |journal=Archaeology |volume=49 |issue=5 |year=1996 |accessdate=2008-06-25}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Cultures of The World Georgia|last1=Spilling |first1=Michael |last2=Wong |first2=Winnie |authorlink= |coauthors= |year=2008 |publisher= |location= |isbn=978-0-7614-3033-9 |page=128 |pages= |url= |accessdate=}}</ref> with other notable sites in [[Greater Iran]] dated 4500 BC and [[Armenia]] 4100 BC, respectively. The world's oldest known winery (dated to 3000 BC) was discovered in [[Areni-1 cave]] in a mountainous area of [[Armenia]].[http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2011/01/110111-oldest-wine-press-making-winery-armenia-science-ucla/].<ref name="8,000-year-old wine">{{cite news |title=Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine |author=David Keys |url=http://accuca.conectia.es/ind281203.htm |work=The Independent |publisher=independent.co.uk |date=28 December 2003 |accessdate=13 January 2011}}</ref><ref name="Archaeology">{{cite journal |author=Mark Berkowitz |year=1996 |month=September/October |title=World's Earliest Wine |journal=Archaeology |volume=49 |issue=5 |publisher=Archaeological Institute of America |accessdate=13 January 2011 |url=http://www.archaeology.org/9609/newsbriefs/wine.html}}</ref><ref name="Wine-making facility">{{cite news |title='Oldest known wine-making facility' found in Armenia |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-12158341 |work=BBC News |publisher=BBC |date=11 January 2011 |accessdate=13 January 2011}}</ref><!--nothing about gene-mapping in this citation--> |

||

Increasingly clear archaeological evidence indicates that domestication of the [[grape]]vine took place during the Early [[Bronze Age]] in the [[Near East]], [[Sumer]] and [[Egypt]] from around the third millennium |

Increasingly clear archaeological evidence indicates that domestication of the [[grape]]vine took place during the Early [[Bronze Age]] in the [[Near East]], [[Sumer]] and [[Egypt]] from around the third millennium BC.<ref>{{cite news | first=Dan | last=Verango | coauthors= | title=White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb | date=2006-05-29 | publisher= | url =http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/columnist/vergano/2006-05-29-tut-white-wine_x.htm | work =USA Today | pages = | accessdate = 2007-09-06 | language = }}</ref> |

||

Evidence of the earliest wine production in [[Balkans]] has been uncovered at archaeological sites in northern [[Greece]] ([[Macedonia (Greece)|Macedonia]]), dated to 4500 BC.<ref name="dsc.discovery.com">[http://dsc.discovery.com/news/2007/03/16/oldgrapes_arc.html?category=archaeology&guid=20070316120000 Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece] Discovery News.</ref> These same sites also contain remnants of the world's earliest evidence of crushed grapes.<ref name="dsc.discovery.com"/> In [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]], wine became a part of recorded history, playing an important role in ancient [[Ceremony|ceremonial life]]. Traces of wild wine dating from the second and first millennia |

Evidence of the earliest wine production in [[Balkans]] has been uncovered at archaeological sites in northern [[Greece]] ([[Macedonia (Greece)|Macedonia]]), dated to 4500 BC.<ref name="dsc.discovery.com">[http://dsc.discovery.com/news/2007/03/16/oldgrapes_arc.html?category=archaeology&guid=20070316120000 Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece] Discovery News.</ref> These same sites also contain remnants of the world's earliest evidence of crushed grapes.<ref name="dsc.discovery.com"/> In [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]], wine became a part of recorded history, playing an important role in ancient [[Ceremony|ceremonial life]]. Traces of wild wine dating from the second and first millennia BC have also been found in China.<ref>[http://www.sytu.edu.cn/zhgjiu/u5-2.htm Wine Production in China 3000 years ago].</ref> |

||

Wine, linked in myth to [[Dionysus]]/[[Bacchus]], was common in [[ancient Greece]] and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]],<ref name="greekwinemakers.com">[http://www.greekwinemakers.com/czone/history/2ancient.shtml The history of wine in ancient Greece] at greekwinemakers.com</ref> and many of today's major wine-producing regions of [[Western Europe]] were established with [[Phoenicia]]n and, later, Roman plantations.<ref name="Phillips pg 37">R. Phillips ''A Short History of Wine'' p. 37 Harper Collins 2000 ISBN 0-06-093737-8</ref> Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the [[Roman Empire]]: many grape varieties and cultivation techniques were known; the design of the [[wine press]] advanced; and [[barrel]]s were developed for storing and shipping wine.<ref name="Phillips pg 37"/> |

Wine, linked in myth to [[Dionysus]]/[[Bacchus]], was common in [[ancient Greece]] and [[Ancient Rome|Rome]],<ref name="greekwinemakers.com">[http://www.greekwinemakers.com/czone/history/2ancient.shtml The history of wine in ancient Greece] at greekwinemakers.com</ref> and many of today's major wine-producing regions of [[Western Europe]] were established with [[Phoenicia]]n and, later, Roman plantations.<ref name="Phillips pg 37">R. Phillips ''A Short History of Wine'' p. 37 Harper Collins 2000 ISBN 0-06-093737-8</ref> Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the [[Roman Empire]]: many grape varieties and cultivation techniques were known; the design of the [[wine press]] advanced; and [[barrel]]s were developed for storing and shipping wine.<ref name="Phillips pg 37"/> |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Prehistory and antiquity== |

==Prehistory and antiquity== |

||

[[File:Archeological sites - wine and oil (English).svg|thumb|right|300px|Archaeological sites of the Neolithic, Copper Age and early Bronze Age in which vestiges of wine-growing or olive-growing have been found.]] |

[[File:Archeological sites - wine and oil (English).svg|thumb|right|300px|Archaeological sites of the Neolithic, Copper Age and early Bronze Age in which vestiges of wine-growing or olive-growing have been found.]] |

||

Little is actually known of the early history of wine. It is plausible that early foragers and farmers made [[alcoholic beverages]] from wild fruits, including grapes of the species ''Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris'', ancestor to modern wine grapes (''[[V. vinifera]]''). This would have become easier following the development of [[pottery]] vessels in the later [[Neolithic]] of the [[Near East]], about 11,000 |

Little is actually known of the early history of wine. It is plausible that early foragers and farmers made [[alcoholic beverages]] from wild fruits, including grapes of the species ''Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris'', ancestor to modern wine grapes (''[[V. vinifera]]''). This would have become easier following the development of [[pottery]] vessels in the later [[Neolithic]] of the [[Near East]], about 11,000 BC. |

||

In his book ''Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), Patrick McGovern argues that the domestication of the Eurasian wine grape and winemaking could have originated in the territory of the modern-day country of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], spreading south from there.<ref>Harrington, Spencer P.M., [http://www.archaeology.org/0403/reviews/wine.html Roots of the Vine] Archeology, Volume 57 Number 2, March/{{Nowrap|April 2004}}.</ref> |

In his book ''Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), Patrick McGovern argues that the domestication of the Eurasian wine grape and winemaking could have originated in the territory of the modern-day country of [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], spreading south from there.<ref>Harrington, Spencer P.M., [http://www.archaeology.org/0403/reviews/wine.html Roots of the Vine] Archeology, Volume 57 Number 2, March/{{Nowrap|April 2004}}.</ref> |

||

The oldest known [[winery]] is located in the [[Areni-1 winery|"Areni-1" cave]] in the [[Vayots Dzor Province]] of [[Armenia]]. Dated around 4100 |

The oldest known [[winery]] is located in the [[Areni-1 winery|"Areni-1" cave]] in the [[Vayots Dzor Province]] of [[Armenia]]. Dated around 4100 BC, the winery contains a wine press, fermentation vats, jars, and cups. Archaeologists also found grape seeds and vines of the species ''V. vinifera''. Commenting on the importance of the find, McGovern said, "The fact that winemaking was already so well developed in 4000 BC suggests that the technology probably goes back much earlier."<ref name="Wine-making facility"/><ref>{{cite news |title=Ancient winery found in Armenia |author=Thomas H. Maugh II |url=http://articles.latimes.com/2011/jan/11/science/la-sci-ancient-winery-20110111 |work=Los Angeles Times |publisher=Los Angeles Times Media Group |date=January 11, 2011 |accessdate=January 13, 2011}}</ref> |

||

Domesticated grapes were abundant in the [[Near East]] from the beginning of the Early [[Bronze Age]], starting in 3200 |

Domesticated grapes were abundant in the [[Near East]] from the beginning of the Early [[Bronze Age]], starting in 3200 BC. There is also increasingly abundant evidence for winemaking in [[Sumer]] and [[Egypt]] in the third millennium BC. The [[ancient Chinese]] made wine from native wild "mountain grapes" like ''[[Vitis thunbergii|V. thunbergii]]''<ref>Eijkhoff, P. [http://www.eykhoff.nl/Wine%20in%20China.pdf Wine in China: its historical and contemporary developments] (2 MiB PDF).</ref> for a time, until they imported domesticated grape seeds from [[Central Asia]] in the second century. Grapes were also an important food. There is slender evidence for earlier domestication of the grape, in the form of pips from [[Chalcolithic]] Tell Shuna in [[Jordan]], but this evidence remains unpublished. |

||

Exactly where wine was first made is still unclear. It could have been anywhere in a vast region stretching from [[North Africa]] to [[Central Asia|Central]]/[[South Asia]], where wild grapes grow. However, the first large-scale production of wine must have been in the region where grapes were first domesticated: the [[Southern Caucasus]] and the [[Near East]]. Wild grapes grow in Georgia, the northern [[Levant]], coastal and southeastern [[Turkey]], northern [[Iran]] and [[Armenia]]. None of these areas can yet be definitively singled out. |

Exactly where wine was first made is still unclear. It could have been anywhere in a vast region stretching from [[North Africa]] to [[Central Asia|Central]]/[[South Asia]], where wild grapes grow. However, the first large-scale production of wine must have been in the region where grapes were first domesticated: the [[Southern Caucasus]] and the [[Near East]]. Wild grapes grow in Georgia, the northern [[Levant]], coastal and southeastern [[Turkey]], northern [[Iran]] and [[Armenia]]. None of these areas can yet be definitively singled out. |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Ancient Greece=== |

===Ancient Greece=== |

||

{{Main|Ancient Greece and wine}} |

{{Main|Ancient Greece and wine}} |

||

[[File:Dionysos vineyard MNE Villa Giulia 106463.jpg|thumb|180px|Dionysus in a vineyard; late 6th-century |

[[File:Dionysos vineyard MNE Villa Giulia 106463.jpg|thumb|180px|Dionysus in a vineyard; late 6th-century BC amphora]] |

||

Much of modern wine culture derives from the practices of the ancient Greeks. While the exact arrival of wine in Greek territory remains obscure, it was certainly known to both the [[Minoan civilization|Minoan]] and [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaean]] cultures.<ref name="greekwinemakers.com"/> Many of the grapes grown in modern Greece are grown there exclusively and are similar or identical to varieties grown in ancient times. Indeed, the most popular modern Greek wine, a strongly aromatic white called [[retsina]], is thought to be a carryover from the ancient practice of lining wine jugs with tree resin, which imparted a distinct flavor to the drink. |

Much of modern wine culture derives from the practices of the ancient Greeks. While the exact arrival of wine in Greek territory remains obscure, it was certainly known to both the [[Minoan civilization|Minoan]] and [[Mycenaean Greece|Mycenaean]] cultures.<ref name="greekwinemakers.com"/> Many of the grapes grown in modern Greece are grown there exclusively and are similar or identical to varieties grown in ancient times. Indeed, the most popular modern Greek wine, a strongly aromatic white called [[retsina]], is thought to be a carryover from the ancient practice of lining wine jugs with tree resin, which imparted a distinct flavor to the drink. |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

| postscript = <!--None--> }}</ref> Dionysus was also known as [[Dionysus|Bacchus]]<ref>In Greek "both votary and god are called Bacchus." (Burkert, ''Greek Religion'' 1985)</ref> (the name later adopted by ancient Romans) and the frenzy he induces as ''bakkheia''. In Homeric mythology, wine is usually served in "[[Krater|mixing bowls]]"—it was not traditionally consumed in an undiluted state—and was referred to as "Juice of the Gods." [[Homer]] frequently refers to the "wine-dark sea" (οἶνωψ πόντος, ''oīnōps póntos''); under the intensely blue Greek sky, the [[Aegean Sea]] as seen from aboard a boat can appear deep purple. |

| postscript = <!--None--> }}</ref> Dionysus was also known as [[Dionysus|Bacchus]]<ref>In Greek "both votary and god are called Bacchus." (Burkert, ''Greek Religion'' 1985)</ref> (the name later adopted by ancient Romans) and the frenzy he induces as ''bakkheia''. In Homeric mythology, wine is usually served in "[[Krater|mixing bowls]]"—it was not traditionally consumed in an undiluted state—and was referred to as "Juice of the Gods." [[Homer]] frequently refers to the "wine-dark sea" (οἶνωψ πόντος, ''oīnōps póntos''); under the intensely blue Greek sky, the [[Aegean Sea]] as seen from aboard a boat can appear deep purple. |

||

The earliest reference to a named wine is from the lyrical poet [[Alkman]] (7th century |

The earliest reference to a named wine is from the lyrical poet [[Alkman]] (7th century BC), who praises "Dénthis," a wine from the western foothills of Mount [[Taygetus]] in [[Messenia]], as "''anthosmías''" ("smelling of flowers"). [[Aristotle]] mentions [[Lemnos Island|Lemnian]] wine, which was probably the same as the modern-day [[Lemnió]] varietal, a red wine with a bouquet of [[oregano]] and [[thyme]]. If so, this makes Lemnió the oldest known varietal still in cultivation. |

||

Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin, as [[amphora]]s with Greek styling and art have been found throughout the area. The Greeks may have been involved in the first appearance of wine in ancient Egypt.<ref>[http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=2146412958&mode=thread&order=06500 year old Mashed grapes found] World's earliest evidence of crushed grapes</ref> They introduced the ''V. vinifera'' [[vine]]<ref name=Jacobson>Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84</ref> and made wine in their numerous colonies in modern-day Italy,<ref name=Fagan>The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p.757</ref> [[Sicily]],<ref name="Sandler">Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p.66</ref> southern France<ref name="Kibler">Medieval France: an encyclopedia, William Westcott Kibler, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p.964</ref> and Spain.<ref name="Jacobson"/> |

Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin, as [[amphora]]s with Greek styling and art have been found throughout the area. The Greeks may have been involved in the first appearance of wine in ancient Egypt.<ref>[http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=2146412958&mode=thread&order=06500 year old Mashed grapes found] World's earliest evidence of crushed grapes</ref> They introduced the ''V. vinifera'' [[vine]]<ref name=Jacobson>Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84</ref> and made wine in their numerous colonies in modern-day Italy,<ref name=Fagan>The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p.757</ref> [[Sicily]],<ref name="Sandler">Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p.66</ref> southern France<ref name="Kibler">Medieval France: an encyclopedia, William Westcott Kibler, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p.964</ref> and Spain.<ref name="Jacobson"/> |

||

===Ancient Egypt=== |

===Ancient Egypt=== |

||

[[File:Ägyptischer Maler um 1500 v. Chr. 001.jpg|thumb|Grape cultivation, winemaking, and commerce in ancient Egypt ''ca.'' 1500 |

[[File:Ägyptischer Maler um 1500 v. Chr. 001.jpg|thumb|Grape cultivation, winemaking, and commerce in ancient Egypt ''ca.'' 1500 BC]] |

||

Wine played an important role in [[ancient Egypt]]ian ceremonial life. A thriving royal winemaking industry was established in the [[Nile Delta]] following the introduction of grape cultivation from the [[Levant]] to Egypt c. 3000 |

Wine played an important role in [[ancient Egypt]]ian ceremonial life. A thriving royal winemaking industry was established in the [[Nile Delta]] following the introduction of grape cultivation from the [[Levant]] to Egypt c. 3000 BC. The industry was most likely the result of trade between Egypt and [[Canaan]] during the Early [[Bronze Age]], commencing from at least the Third Dynasty ([[26th century BC|2650]]–[[25th century BC|2575 BC]]), the beginning of the [[Old Kingdom]] period ([[26th century BC|2650]]–[[21st century BC|2152 BC]]). Winemaking scenes on [[tomb]] walls, and the offering lists that accompanied them, included wine that was definitely produced in the deltaic [[vineyard]]s. By the end of the Old Kingdom, five wines, all probably produced in the Delta, constitute a canonical set of provisions, or fixed "menu," for the afterlife. |

||

Wine in ancient [[Egypt]] was predominantly red; however, a recent discovery has revealed the first evidence of white wine there. Residue from five clay [[amphora]]s from [[Pharaoh]] [[Tutankhamun]]'s tomb yielded traces of white wine.<ref>[http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/columnist/vergano/2006-05-29-tut-white-wine_x.htm White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb]. ''USA Today'', {{Nowrap|29 May}} 2006.</ref> Finds in nearby containers led the same study to establish that [[Shedeh]], the most precious drink in ancient Egypt, was made from red grapes, not [[pomegranate]]s as previously thought.<ref>Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol 33, Iss 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 98–101.</ref> |

Wine in ancient [[Egypt]] was predominantly red; however, a recent discovery has revealed the first evidence of white wine there. Residue from five clay [[amphora]]s from [[Pharaoh]] [[Tutankhamun]]'s tomb yielded traces of white wine.<ref>[http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/columnist/vergano/2006-05-29-tut-white-wine_x.htm White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb]. ''USA Today'', {{Nowrap|29 May}} 2006.</ref> Finds in nearby containers led the same study to establish that [[Shedeh]], the most precious drink in ancient Egypt, was made from red grapes, not [[pomegranate]]s as previously thought.<ref>Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol 33, Iss 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 98–101.</ref> |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

===Ancient China=== |

===Ancient China=== |

||

[[File:CMOC Treasures of Ancient China exhibit - bronze zun.jpg|upright|thumb|150px|right|A bronze wine storage vessel from the [[Shang Dynasty]] (1600–1046 |

[[File:CMOC Treasures of Ancient China exhibit - bronze zun.jpg|upright|thumb|150px|right|A bronze wine storage vessel from the [[Shang Dynasty]] (1600–1046 BC)]] |

||

[[File:18th cent BC wine vessel.jpg|upright|thumb|left|150px|A Chinese wine vessel from the 18th century |

[[File:18th cent BC wine vessel.jpg|upright|thumb|left|150px|A Chinese wine vessel from the 18th century BC]] |

||

{{Main|Chinese alcoholic beverages|Wine in China}} |

{{Main|Chinese alcoholic beverages|Wine in China}} |

||

Following the [[Han Dynasty]] (202 |

Following the [[Han Dynasty]] (202 BC–220 AD), emissary [[Zhang Qian]]'s exploration of the [[Western Regions]] in the second century BC, and contact with [[Hellenistic civilization|Hellenistic kingdoms]] such as [[Dayuan|Fergana]], [[Greco-Bactrian Kingdom|Bactria]], and the [[Indo-Greek Kingdom]], high-quality grapes (i.e. ''[[Vitis vinifera|V. vinifera]]'') were introduced into China and [[Chinese grape wine]] (called ''putao jiu'' in Chinese) was first produced.<ref>http://monkeytree.org/silkroad/zhangqian.html</ref><ref name="gernet 134 135">Gernet, Jacques (1962). ''Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276''. Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0. Page 134–135.</ref><ref name="temple 1986 101"/> Prior to Zhang Qian's travels, wild mountain grapes were used to make wine, notably ''V. thunbergii'' and ''V. filifolia'', described in the ''Classical Pharmacopoeia of the Heavenly Husbandman''.<ref name="temple 1986 101">Temple, Robert. (1986). ''The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention''. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Page 101.</ref> |

||

[[Rice wine]] remained the most common wine in China, since grape wine was still considered exotic and reserved largely for the emperor's table during the [[Tang Dynasty]] (618–907), and was not popularly consumed by the [[Gentry (China)|literati gentry class]] until the [[Song Dynasty]] (960–1279).<ref name="gernet 134 135"/> The fact that rice wine was more common than grape wine was noted even by the [[Venice|Venetian]] traveler [[Marco Polo]] when he ventured to China in the 1280s.<ref name="gernet 134 135"/> As noted by [[Shen Kuo]] (1031–1095) in his ''[[Dream Pool Essays]]'', an old phrase in China amongst the [[Four occupations|gentry class]] was having the company of "drinking guests" (''jiuke''), which was a figure of speech for drinking wine, playing the [[Guqin|Chinese zither]], playing [[Xiangqi|Chinese chess]], [[Zen]] [[Buddhist meditation]], ink ([[Chinese calligraphy|calligraphy]] and [[Chinese painting|painting]]), [[Chinese tea|tea drinking]], [[alchemy]], [[Chinese poetry|chanting poetry]], and conversation.<ref>Lian, Xianda. "The Old Drunkard Who Finds Joy in His Own Joy-Elitist Ideas in Ouyang Xiu's Informal Writings," ''Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR)'' (Volume 23, 2001): 1–29. Page 20</ref> |

[[Rice wine]] remained the most common wine in China, since grape wine was still considered exotic and reserved largely for the emperor's table during the [[Tang Dynasty]] (618–907), and was not popularly consumed by the [[Gentry (China)|literati gentry class]] until the [[Song Dynasty]] (960–1279).<ref name="gernet 134 135"/> The fact that rice wine was more common than grape wine was noted even by the [[Venice|Venetian]] traveler [[Marco Polo]] when he ventured to China in the 1280s.<ref name="gernet 134 135"/> As noted by [[Shen Kuo]] (1031–1095) in his ''[[Dream Pool Essays]]'', an old phrase in China amongst the [[Four occupations|gentry class]] was having the company of "drinking guests" (''jiuke''), which was a figure of speech for drinking wine, playing the [[Guqin|Chinese zither]], playing [[Xiangqi|Chinese chess]], [[Zen]] [[Buddhist meditation]], ink ([[Chinese calligraphy|calligraphy]] and [[Chinese painting|painting]]), [[Chinese tea|tea drinking]], [[alchemy]], [[Chinese poetry|chanting poetry]], and conversation.<ref>Lian, Xianda. "The Old Drunkard Who Finds Joy in His Own Joy-Elitist Ideas in Ouyang Xiu's Informal Writings," ''Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR)'' (Volume 23, 2001): 1–29. Page 20</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:58, 7 January 2013

The history of wine spans thousands of years and is closely intertwined with the history of agriculture, cuisine, civilization and humanity itself. Archaeological evidence suggests that the earliest known wine production occurred in what is now the country of Georgia around 7000 BC,[1][2][3] with other notable sites in Greater Iran dated 4500 BC and Armenia 4100 BC, respectively. The world's oldest known winery (dated to 3000 BC) was discovered in Areni-1 cave in a mountainous area of Armenia.[1].[4][5][6] Increasingly clear archaeological evidence indicates that domestication of the grapevine took place during the Early Bronze Age in the Near East, Sumer and Egypt from around the third millennium BC.[7]

Evidence of the earliest wine production in Balkans has been uncovered at archaeological sites in northern Greece (Macedonia), dated to 4500 BC.[8] These same sites also contain remnants of the world's earliest evidence of crushed grapes.[8] In Egypt, wine became a part of recorded history, playing an important role in ancient ceremonial life. Traces of wild wine dating from the second and first millennia BC have also been found in China.[9]

Wine, linked in myth to Dionysus/Bacchus, was common in ancient Greece and Rome,[10] and many of today's major wine-producing regions of Western Europe were established with Phoenician and, later, Roman plantations.[11] Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the Roman Empire: many grape varieties and cultivation techniques were known; the design of the wine press advanced; and barrels were developed for storing and shipping wine.[11]

Following the decline of Rome and its industrial-scale wine production for export, the Christian Church in medieval Europe became a firm supporter of wine, necessary for celebration of the Catholic Mass. Whereas wine was forbidden in medieval Islamic cultures, its use in Christian libation was widely tolerated. Geber and other Muslim chemists pioneered the distillation of wine for Islamic medicinal and industrial purposes such as perfume.[12] Wine production gradually increased, with consumption burgeoning from the 15th century onwards. Wine production survived the devastating Phylloxera louse of 1887 and eventually spread to numerous regions throughout the world.

Prehistory and antiquity

Little is actually known of the early history of wine. It is plausible that early foragers and farmers made alcoholic beverages from wild fruits, including grapes of the species Vitis vinifera subsp. sylvestris, ancestor to modern wine grapes (V. vinifera). This would have become easier following the development of pottery vessels in the later Neolithic of the Near East, about 11,000 BC.

In his book Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), Patrick McGovern argues that the domestication of the Eurasian wine grape and winemaking could have originated in the territory of the modern-day country of Georgia, spreading south from there.[13]

The oldest known winery is located in the "Areni-1" cave in the Vayots Dzor Province of Armenia. Dated around 4100 BC, the winery contains a wine press, fermentation vats, jars, and cups. Archaeologists also found grape seeds and vines of the species V. vinifera. Commenting on the importance of the find, McGovern said, "The fact that winemaking was already so well developed in 4000 BC suggests that the technology probably goes back much earlier."[6][14]

Domesticated grapes were abundant in the Near East from the beginning of the Early Bronze Age, starting in 3200 BC. There is also increasingly abundant evidence for winemaking in Sumer and Egypt in the third millennium BC. The ancient Chinese made wine from native wild "mountain grapes" like V. thunbergii[15] for a time, until they imported domesticated grape seeds from Central Asia in the second century. Grapes were also an important food. There is slender evidence for earlier domestication of the grape, in the form of pips from Chalcolithic Tell Shuna in Jordan, but this evidence remains unpublished.

Exactly where wine was first made is still unclear. It could have been anywhere in a vast region stretching from North Africa to Central/South Asia, where wild grapes grow. However, the first large-scale production of wine must have been in the region where grapes were first domesticated: the Southern Caucasus and the Near East. Wild grapes grow in Georgia, the northern Levant, coastal and southeastern Turkey, northern Iran and Armenia. None of these areas can yet be definitively singled out.

Legends of discovery

There are many apocryphal tales about the origins of wine. Biblical accounts tell of Noah and his sons producing wine at the base of Mount Ararat.

According to a Persian tale, legendary King Jamshid banished one of his harem ladies from the kingdom, causing her to become despondent and wishing to commit suicide. Going to the king's warehouse, the woman sought out a jar marked "poison" containing the remnants of grapes that had spoiled and deemed undrinkable. Unknown to her, the "spoilage" was actually the result of fermentation (the breakdown of the grapes' sugar by yeast into alcohol). She discovered the effects after drinking to be pleasant and her spirits were lifted. She took her discovery to the king, who became so enamored of this new "wine" beverage that he not only accepted the woman back into his harem but also decreed that all grapes grown in Persepolis would be devoted to winemaking. While most wine historians view this story as pure legend, there is archaeological evidence that wine was known and extensively traded by the early Persian kings.[16]

Phoenicia

As recipients of winemaking knowledge from areas to the east, the Phoenicians were instrumental in distributing wine, wine grapes and winemaking technology throughout the Mediterranean region through their extensive trade network. Their use of amphoras for transporting wine was widely adopted and Phoenician-distributed grape varieties were important in the development of the wine industries of Rome and Greece.

Ancient Greece

Much of modern wine culture derives from the practices of the ancient Greeks. While the exact arrival of wine in Greek territory remains obscure, it was certainly known to both the Minoan and Mycenaean cultures.[10] Many of the grapes grown in modern Greece are grown there exclusively and are similar or identical to varieties grown in ancient times. Indeed, the most popular modern Greek wine, a strongly aromatic white called retsina, is thought to be a carryover from the ancient practice of lining wine jugs with tree resin, which imparted a distinct flavor to the drink.

Evidence from archaeological sites in Greece, in the form of 6,500-year-old grape remnants, represents the earliest known appearance of wine production in Europe.[8] The "feast of the wine" (me-tu-wo ne-wo) was a festival in Mycenaean Greece celebrating the "month of the new wine."[17][18][19] Several ancient sources, such as the Roman writer Pliny the Elder, describe the ancient Greek method of using partly dehydrated gypsum before fermentation, and some type of lime after fermentation, to reduce acidity. The Greek writer Theophrastus provides the oldest known description of this aspect of Greek winemaking.[20][21]

Dionysus, the Greek god of revelry and wine—frequently referred to in the works of Homer and Aesop—was sometimes given the epithet "Acratophorus," by which he was designated as the giver of unmixed wine.[22][23] Dionysus was also known as Bacchus[24] (the name later adopted by ancient Romans) and the frenzy he induces as bakkheia. In Homeric mythology, wine is usually served in "mixing bowls"—it was not traditionally consumed in an undiluted state—and was referred to as "Juice of the Gods." Homer frequently refers to the "wine-dark sea" (οἶνωψ πόντος, oīnōps póntos); under the intensely blue Greek sky, the Aegean Sea as seen from aboard a boat can appear deep purple.

The earliest reference to a named wine is from the lyrical poet Alkman (7th century BC), who praises "Dénthis," a wine from the western foothills of Mount Taygetus in Messenia, as "anthosmías" ("smelling of flowers"). Aristotle mentions Lemnian wine, which was probably the same as the modern-day Lemnió varietal, a red wine with a bouquet of oregano and thyme. If so, this makes Lemnió the oldest known varietal still in cultivation.

Greek wine was widely known and exported throughout the Mediterranean basin, as amphoras with Greek styling and art have been found throughout the area. The Greeks may have been involved in the first appearance of wine in ancient Egypt.[25] They introduced the V. vinifera vine[26] and made wine in their numerous colonies in modern-day Italy,[27] Sicily,[28] southern France[29] and Spain.[26]

Ancient Egypt

Wine played an important role in ancient Egyptian ceremonial life. A thriving royal winemaking industry was established in the Nile Delta following the introduction of grape cultivation from the Levant to Egypt c. 3000 BC. The industry was most likely the result of trade between Egypt and Canaan during the Early Bronze Age, commencing from at least the Third Dynasty (2650–2575 BC), the beginning of the Old Kingdom period (2650–2152 BC). Winemaking scenes on tomb walls, and the offering lists that accompanied them, included wine that was definitely produced in the deltaic vineyards. By the end of the Old Kingdom, five wines, all probably produced in the Delta, constitute a canonical set of provisions, or fixed "menu," for the afterlife.

Wine in ancient Egypt was predominantly red; however, a recent discovery has revealed the first evidence of white wine there. Residue from five clay amphoras from Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb yielded traces of white wine.[30] Finds in nearby containers led the same study to establish that Shedeh, the most precious drink in ancient Egypt, was made from red grapes, not pomegranates as previously thought.[31]

As with much of the ancient Middle East, Egypt's lower classes preferred beer as a daily drink rather than wine, a taste likely inherited from the Sumerians. However, wine was well-known, especially near the Mediterranean coast, and figures prominently in the ritual life of the Jewish people, going back to the earliest known records of the faith. The Tanakh mentions it prominently in many locations as both a boon and a curse, and wine drunkenness serves as a major theme in a number of Bible stories.

Much superstition surrounded wine-drinking in early Egyptian times, largely due to its resemblance to blood. In Plutarch's Moralia, he mentions that, prior to the reign of Psammetichus[disambiguation needed], the ancient kings did not drink wine, "nor use it in libation as something dear to the gods, thinking it to be the blood of those who had once battled against the gods and from whom, when they had fallen and had become commingled with the earth, they believed vines to have sprung." This was considered to be the reason why drunkenness "drives men out of their senses and crazes them, inasmuch as they are then filled with the blood of their forbears."[32]

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire had an immense impact on the development of viticulture and oenology. Wine was an integral part of the Roman diet and winemaking became a precise business. Vitruvius's De architectura (I.4.2) noted how wine storage rooms were built facing north, "since that quarter is never subject to change but is always constant and unshifting."

As the Roman Empire expanded, wine production in the provinces grew to the point where it was competing with Roman wines. Virtually all of the major wine-producing regions of Western Europe today were established during the Roman Imperial era.

Winemaking technology improved considerably during the time of the Roman Empire. Many grape varieties and cultivation techniques were developed, and barrels (invented by the Gauls) and later, glass bottles (invented by the Syrians) began to compete with terracotta amphoras for storing and shipping wine. Following the Greek invention of the screw, wine presses became common in Roman villas. The Romans also created a precursor to today's appellation systems, as certain regions gained reputations for their fine wines.

Wine, perhaps mixed with herbs and minerals, was assumed to serve medicinal purposes. During Roman times, the upper classes might dissolve pearls in wine for better health. Cleopatra created her own legend by promising Mark Antony she would "drink the value of a province" in one cup of wine, after which she drank an expensive pearl with a cup of the beverage.[21] When the Western Roman Empire fell around 500 AD, Europe entered a period of invasions and social turmoil, with the Roman Catholic Church as the only stable social structure. Through the Church, grape-growing and winemaking technology, essential for the Mass, were preserved.[33]

Ancient China

Following the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD), emissary Zhang Qian's exploration of the Western Regions in the second century BC, and contact with Hellenistic kingdoms such as Fergana, Bactria, and the Indo-Greek Kingdom, high-quality grapes (i.e. V. vinifera) were introduced into China and Chinese grape wine (called putao jiu in Chinese) was first produced.[34][35][36] Prior to Zhang Qian's travels, wild mountain grapes were used to make wine, notably V. thunbergii and V. filifolia, described in the Classical Pharmacopoeia of the Heavenly Husbandman.[36] Rice wine remained the most common wine in China, since grape wine was still considered exotic and reserved largely for the emperor's table during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), and was not popularly consumed by the literati gentry class until the Song Dynasty (960–1279).[35] The fact that rice wine was more common than grape wine was noted even by the Venetian traveler Marco Polo when he ventured to China in the 1280s.[35] As noted by Shen Kuo (1031–1095) in his Dream Pool Essays, an old phrase in China amongst the gentry class was having the company of "drinking guests" (jiuke), which was a figure of speech for drinking wine, playing the Chinese zither, playing Chinese chess, Zen Buddhist meditation, ink (calligraphy and painting), tea drinking, alchemy, chanting poetry, and conversation.[37]

Medieval period

Medieval Middle East

In the Arabian peninsula before the advent of Islam, wine was traded by Aramaic merchants, as the climate was not well-suited to the growing of vines. Many other types of fermented drinks, however, were produced in the 5th and 6th centuries, including date and honey wines.

The Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries brought many territories under Muslim control. Alcoholic drinks were prohibited by law, but the production of alcohol, wine in particular, seems to have thrived. Wine was a subject for many poets, even under Islamic rule, and many khalifas used to drink alcoholic beverages during their social and private meetings. Egyptian Jews leased vineyards from the Fatimid and Mamluk governments, produced wine for sacramental and medicinal use, and traded wine throughout the Eastern Mediterranean. Christian monasteries in the Levant and Iraq often cultivated grapevines; they then distributed their vintages in taverns located on monastery grounds. Zoroastrians in Persia and Central Asia also engaged in the production of wine. Though not much is known about their wine trade, they did become known for their taverns.

Wine in general found an industrial use in the medieval Middle East as feedstock after advances in distillation by Muslim alchemists allowed for the production of relatively pure ethanol, which was used in the perfume industry. Wine was also for the first time distilled into brandy during this period.

Medieval Europe

In the Middle Ages, wine was the common drink of all social classes in the south, where grapes were cultivated. In the north and east, where few if any grapes were grown, beer and ale were the usual beverages of both commoners and nobility. Wine was exported to the northern regions, but because of its relatively high expense was seldom consumed by the lower classes. Since wine was necessary, however, for the celebration of the Catholic Mass, assuring a supply was crucial. The Benedictine monks became one of the largest producers of wine in France and Germany, followed closely by the Cistercians. Other orders, such as the Carthusians, the Templars, and the Carmelites, are also notable both historically and in modern times as wine producers. The Benedictines owned vineyards in Champagne (Dom Perignon was a Benedictine monk), Burgundy, and Bordeaux in France, and in the Rheingau and Franconia in Germany. In 1435 Count John IV of Katzenelnbogen, a wealthy member of the Holy Roman high nobility near Frankfurt, was the first to plant Riesling, the most important German grape. The nearby winemaking monks made it into an industry, producing enough wine to ship all over Europe for secular use. In Portugal, a country with one of the oldest wine traditions, the first appellation system in the world was created.

A housewife of the merchant class or a servant in a noble household would have served wine at every meal, and had a selection of reds and whites alike. Home recipes for meads from this period are still in existence, along with recipes for spicing and masking flavors in wines, including the simple act of adding a small amount of honey. As wines were kept in barrels, they were not extensively aged, and thus drunk quite young. To offset the effects of heavy alcohol consumption, wine was frequently watered down at a ratio of four or five parts water to one of wine.

One medieval application of wine was the use of snake-stones (banded agate resembling the figural rings on a snake) dissolved in wine as a remedy for snake bites, which shows an early understanding of the effects of alcohol on the central nervous system in such situations.[21]

Jofroi of Waterford, a 13th-century Dominican, wrote a catalogue of all the known wines and ales of Europe, describing them with great relish and recommending them to academics and counsellors.

Modern era

Spread and development in the Americas

European grape varieties were first brought to what is now Mexico by the first Spanish conquistadors to provide the necessities of the Catholic Holy Eucharist. Planted at Spanish missions, one variety came to be known as the Mission grape and is still planted today in small amounts. Succeeding waves of immigrants imported French, Italian and German grapes, although wine from those native to the Americas (whose flavors can be distinctly different) is also produced. Mexico became the most important wine producer starting in the 16th century, to the extent that its output began to affect Spanish commercial production. In this competitive climate, the Spanish king sent an executive order to halt Mexico 's production of wines and the planting of vineyards.

During the devastating phylloxera blight in late-19th-century Europe, it was found that native American vines were immune to the pest. French-American hybrid grapes were developed and saw some use in Europe, but more important was the practice of grafting European grapevines to American rootstocks to protect vineyards from the insect. The practice continues to this day wherever phylloxera is present.

Today, wine in the Americas is often associated with Argentina, California and Chile, all of which produce a wide variety of wines, from inexpensive jug wines to high-quality varietals and proprietary blends. Most of the wine production in the Americas is based on Old World grape varieties, and wine-growing regions there have often "adopted" grapes that have become particularly closely identified with them. California's Zinfandel (from Croatia and Southern Italy), Argentina's Malbec, and Chile's Carmenère (both from France) are well-known examples.

Until the latter half of the 20th century, American wine was generally viewed as inferior to that of Europe. However, with the surprisingly favorable American showing at the Paris Wine tasting of 1976, New World wine began to garner respect in the land of wine's origins.

Developments in Europe

In the late 19th century, the phylloxera louse brought widespread destruction to grapevines, wine production, and those whose livelihoods depended on them; far-reaching repercussions included the loss of many indigenous varieties. Lessons learned from the infestation led to the positive transformation of Europe's wine industry. Bad vineyards were uprooted and their land turned to better uses. Some of France's best butter and cheese, for example, is now made from cows that graze on Charentais soil, which was previously covered with vines. Cuvées were also standardized, important in creating certain wines as they are known today; Champagne and Bordeaux finally achieved the grape mixes that now define them. In the Balkans, where phylloxera had had little impact, the local varieties survived. However, the uneven transition from Ottoman occupation has meant only gradual transformation in many vineyards. It is only in recent times that local varieties have gained recognition beyond "mass-market" wines like retsina.

Australia, New Zealand and South Africa

In the context of wine, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and other countries without a wine tradition are considered New World producers. Wine production began in the Cape Province of what is now South Africa in the 1680s as a business for supplying ships. Australia's First Fleet (1788) brought cuttings of vines from South Africa, although initial plantings failed and the first successful vineyards were established in the early 19th century. Until quite late in the 20th century, the product of these countries was not well known outside their small export markets. For example, Australia exported mainly to the United Kingdom; New Zealand retained most of its wine for domestic consumption; and South Africa was often isolated from the world market because of apartheid). However, with the increase in mechanization and scientific advances in winemaking, these countries became known for high-quality wine. A notable exception to the foregoing is that the Cape Province was the largest exporter of wine to Europe in the 18th century.

See also

- Chinese alcoholic beverages

- History of French wine

- History of Portuguese wine

- History of Champagne

- History of the wine press

- Wine in China

References

- ^ Keys, David (2003-12-28). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. Retrieved 2011-03-20.

- ^ Berkowitz, Mark (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ Spilling, Michael; Wong, Winnie (2008). Cultures of The World Georgia. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7614-3033-9.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ David Keys (28 December 2003). "Now that's what you call a real vintage: professor unearths 8,000-year-old wine". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Mark Berkowitz (1996). "World's Earliest Wine". Archaeology. 49 (5). Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "'Oldest known wine-making facility' found in Armenia". BBC News. BBC. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ Verango, Dan (2006-05-29). "White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-09-06.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Ancient Mashed Grapes Found in Greece Discovery News.

- ^ Wine Production in China 3000 years ago.

- ^ a b The history of wine in ancient Greece at greekwinemakers.com

- ^ a b R. Phillips A Short History of Wine p. 37 Harper Collins 2000 ISBN 0-06-093737-8

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources

- ^ Harrington, Spencer P.M., Roots of the Vine Archeology, Volume 57 Number 2, March/April 2004.

- ^ Thomas H. Maugh II (January 11, 2011). "Ancient winery found in Armenia". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times Media Group. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ Eijkhoff, P. Wine in China: its historical and contemporary developments (2 MiB PDF).

- ^ T. Pellechia Wine: The 8,000-Year-Old Story of the Wine Trade pg XI–XII Running Press, London 2006 ISBN 1-56025-871-3

- ^ Mycenaean and Late Cycladic Religion and Religious Architecture, Dartmouth College

- ^ T.G. Palaima, The Last days of Pylos Polity, Université de Liège

- ^ James C. Wright, The Mycenaean feast, American School of Classical Studies, 2004, on Google books

- ^ Caley, Earle (1956). Theophrastis On Stone. Ohio State University.Online version: Gypsum/lime in wine

- ^ a b c Wine Drinking and Making in Antiquity: Historical References on the Role of Gemstones Many classic scientists such as Al Biruni, Theophrastus, Georg Agricola, Albertus Magnus as well as newer authors such as George Frederick Kunz describe the many talismanic, medicinal uses of minerals and wine combined.

- ^ Pausanias, viii. 39. § 4

- ^ Schmitz, Leonhard (1867). "Acratophorus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Vol. 1. Boston, MA. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ In Greek "both votary and god are called Bacchus." (Burkert, Greek Religion 1985)

- ^ year old Mashed grapes found World's earliest evidence of crushed grapes

- ^ a b Introduction to Wine Laboratory Practices and Procedures, Jean L. Jacobson, Springer, p.84

- ^ The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Brian Murray Fagan, 1996 Oxford Univ Pr, p.757

- ^ Wine: A Scientific Exploration, Merton Sandler, Roger Pinder, CRC Press, p.66

- ^ Medieval France: an encyclopedia, William Westcott Kibler, Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, p.964

- ^ White wine turns up in King Tutankhamen's tomb. USA Today, 29 May 2006.

- ^ Maria Rosa Guasch-Jané, Cristina Andrés-Lacueva, Olga Jáuregui and Rosa M. Lamuela-Raventós, The origin of the ancient Egyptian drink Shedeh revealed using LC/MS/MS, Journal of Archaeological Science, Vol 33, Iss 1, Jan. 2006, pp. 98–101.

- ^ "Isis & Osiris". University of Chicago.

- ^ History of Wine

- ^ http://monkeytree.org/silkroad/zhangqian.html

- ^ a b c Gernet, Jacques (1962). Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion, 1250-1276. Translated by H. M. Wright. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0720-0. Page 134–135.

- ^ a b Temple, Robert. (1986). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention. With a forward by Joseph Needham. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-62028-2. Page 101.

- ^ Lian, Xianda. "The Old Drunkard Who Finds Joy in His Own Joy-Elitist Ideas in Ouyang Xiu's Informal Writings," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) (Volume 23, 2001): 1–29. Page 20