East End of London: Difference between revisions

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 5 sources, flagging 0 as dead, and archiving 82 sources. #IABot |

|||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

Initially, the German commanders were reluctant to bomb London, fearing retaliation against Berlin. On 24 August 1940, a single aircraft, tasked to bomb [[Tilbury]], accidentally bombed Stepney, Bethnal Green and the City. The following night the [[RAF]] retaliated by mounting a forty aircraft raid on Berlin, with a second attack three days later. The [[Luftwaffe]] changed its strategy from attacking shipping and airfields to attacking cities. The City and West End were designated 'Target Area B'; the East End and docks were 'Target Area A'. The first raid occurred at 4:30 p.m. on 7 September and consisted of 150 [[Dornier Do 17|Dornier]] and [[Heinkel He 111|Heinkel]] bombers and large numbers of fighters. This was followed by a second wave of 170 bombers. [[Silvertown]] and [[Canning Town]] bore the brunt of this first attack.<ref name=palmer/> |

Initially, the German commanders were reluctant to bomb London, fearing retaliation against Berlin. On 24 August 1940, a single aircraft, tasked to bomb [[Tilbury]], accidentally bombed Stepney, Bethnal Green and the City. The following night the [[RAF]] retaliated by mounting a forty aircraft raid on Berlin, with a second attack three days later. The [[Luftwaffe]] changed its strategy from attacking shipping and airfields to attacking cities. The City and West End were designated 'Target Area B'; the East End and docks were 'Target Area A'. The first raid occurred at 4:30 p.m. on 7 September and consisted of 150 [[Dornier Do 17|Dornier]] and [[Heinkel He 111|Heinkel]] bombers and large numbers of fighters. This was followed by a second wave of 170 bombers. [[Silvertown]] and [[Canning Town]] bore the brunt of this first attack.<ref name=palmer/> |

||

Between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, a sustained bombing campaign was mounted. It began with the bombing of London for 57 successive nights,<ref name=Docklands>The weather closed in on the night of 2 November 1940, otherwise London would have been bombed for 76 successive nights. [http://www.museumindocklands.org.uk/English/EventsExhibitions/Themes/DocklandsWar/Docklandsatwar1.htm ''Docklands at War – The Blitz''] |

Between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, a sustained bombing campaign was mounted. It began with the bombing of London for 57 successive nights,<ref name=Docklands>The weather closed in on the night of 2 November 1940, otherwise London would have been bombed for 76 successive nights. [http://www.museumindocklands.org.uk/English/EventsExhibitions/Themes/DocklandsWar/Docklandsatwar1.htm ''Docklands at War – The Blitz''] The [[Museum in Docklands]] accessed 27 February 2008 {{wayback|url=http://www.museumindocklands.org.uk/English/EventsExhibitions/Themes/DocklandsWar/Docklandsatwar1.htm |date=20071206110526 |df=y }}</ref> an era known as '[[the Blitz]]'. East London was targeted because the area was a centre for imports and storage of raw materials for the war effort, and the German military command felt that support for the war could be damaged among the mainly working class inhabitants. On the first night of the Blitz, 430 civilians were killed and 1,600 seriously wounded.<ref name=Docklands/> The populace responded by evacuating children and the vulnerable to the country<ref>An earlier planned evacuation had been met with intense distrust in the East End, families preferring to remain united and in their own homes (see Palmer, 1989).</ref> and digging in, constructing [[Anderson shelter]]s in their gardens and [[Morrison shelter]]s in their houses, or going to communal shelters built in local public spaces.<ref>The man responsible for the shelter programme was [[Charles Kay]] MP, London's Joint Regional Commissioner, and a former councillor and Mayor of Poplar. Elected on a pro-war ticket within the first 30 weeks of war (see Palmer, 1989, p. 139)</ref> On 10 September 1940, 73 civilians, including women and children preparing for evacuation, were killed when a bomb hit the South Hallsville School. Although the official death toll is 73,<ref>{{cite web|author=Andrew Swinney|url=http://webapps.newham.gov.uk/History_canningtown/page18a.htm |title=HISTORY TOUR – Disaster! 2 |publisher=Webapps.newham.gov.uk |date=17 February 2003 |accessdate=23 July 2011}}</ref> many local people believed it must have been higher. Some estimates say 400 or even 600 may have lost their lives during this raid on [[Canning Town]].<ref>[http://www.age-exchange.org.uk/eastend/secondworldwar/index.html ''Remembering the East End:The Second World War''] Age-exchange accessed 14 November 2007</ref> |

||

[[File:WWII London Blitz East London.jpg|thumb|right|Children of an eastern suburb of London, made homeless by the Blitz]] |

[[File:WWII London Blitz East London.jpg|thumb|right|Children of an eastern suburb of London, made homeless by the Blitz]] |

||

| Line 174: | Line 174: | ||

The high levels of poverty in the East End have, throughout history, corresponded with a high incidence of crime. From earliest times, crime depended, as did labour, on the importing of goods to London, and their interception in transit. Theft occurred in the river, on the quayside and in transit to the City warehouses. This was why, in the 17th century, the [[British East India Company|East India Company]] built high-walled docks at [[Blackwall, London|Blackwall]] and had them guarded to minimise the vulnerability of their cargoes. Armed convoys would then take the goods to the company's secure compound in the City. The practice led to the creation of ever-larger docks throughout the area, and large roads to drive through the crowded 19th century slums to carry goods from the docks.<ref name=palmer/> |

The high levels of poverty in the East End have, throughout history, corresponded with a high incidence of crime. From earliest times, crime depended, as did labour, on the importing of goods to London, and their interception in transit. Theft occurred in the river, on the quayside and in transit to the City warehouses. This was why, in the 17th century, the [[British East India Company|East India Company]] built high-walled docks at [[Blackwall, London|Blackwall]] and had them guarded to minimise the vulnerability of their cargoes. Armed convoys would then take the goods to the company's secure compound in the City. The practice led to the creation of ever-larger docks throughout the area, and large roads to drive through the crowded 19th century slums to carry goods from the docks.<ref name=palmer/> |

||

No police force operated in London before the 1750s. Crime and disorder were dealt with by a system of magistrates and volunteer parish constables, with strictly limited jurisdiction. Salaried constables were introduced by 1792, although they were few in number and their power and jurisdiction continued to derive from local magistrates, who ''in extremis'' could be backed by militias. In 1798, England's first [[Marine Police Force]] was formed by magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and a Master Mariner, [[John Harriott]], to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the [[Pool of London]] and the lower reaches of the river. Its base was (and remains) in [[Wapping]] High Street. It is now known as the [[Marine Support Unit]].<ref>[http://www.met.police.uk/msu/history.htm ''History of the Marine Support Unit''] |

No police force operated in London before the 1750s. Crime and disorder were dealt with by a system of magistrates and volunteer parish constables, with strictly limited jurisdiction. Salaried constables were introduced by 1792, although they were few in number and their power and jurisdiction continued to derive from local magistrates, who ''in extremis'' could be backed by militias. In 1798, England's first [[Marine Police Force]] was formed by magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and a Master Mariner, [[John Harriott]], to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the [[Pool of London]] and the lower reaches of the river. Its base was (and remains) in [[Wapping]] High Street. It is now known as the [[Marine Support Unit]].<ref>[http://www.met.police.uk/msu/history.htm ''History of the Marine Support Unit''] ([[Metropolitan Police Service|Metropolitan Police]]) accessed 24 January 2007 {{wayback|url=http://www.met.police.uk/msu/history.htm |date=20070716200107 |df=y }}</ref> |

||

In 1829, the [[Metropolitan Police Force]] was formed, with a remit to patrol within {{convert|7|mi|km|0}} of [[Charing Cross]], with a force of 1,000 men in 17 divisions, including 'H' division, based in Stepney. Each division was controlled by a superintendent, under whom were four inspectors and sixteen sergeants. The regulations demanded that recruits should be under thirty-five years of age, well built, at least {{convert|5|ft|7|in|m|sing=on}} in height, literate and of good character.<ref name=metro>[http://www.met.police.uk/history/records.htm ''Records of Service''] (Metropolitan Police) accessed 23 October 2007</ref> |

In 1829, the [[Metropolitan Police Force]] was formed, with a remit to patrol within {{convert|7|mi|km|0}} of [[Charing Cross]], with a force of 1,000 men in 17 divisions, including 'H' division, based in Stepney. Each division was controlled by a superintendent, under whom were four inspectors and sixteen sergeants. The regulations demanded that recruits should be under thirty-five years of age, well built, at least {{convert|5|ft|7|in|m|sing=on}} in height, literate and of good character.<ref name=metro>[http://www.met.police.uk/history/records.htm ''Records of Service''] (Metropolitan Police) accessed 23 October 2007</ref> |

||

| Line 197: | Line 197: | ||

Many disasters have befallen the residents of the East End, both in war and in peace. In particular, as a maritime port, [[Plague (disease)|plague]] and pestilence have disproportionately fallen on the residents of the East End. The area most afflicted by the [[Great Plague of London|Great Plague (1665)]] was Spitalfields,<ref>Plague deaths measured at more than 3000 deaths per 478 sq yards in Spitalfields in 1665 (source: ''London from the Air'')</ref> and cholera epidemics broke out in Limehouse in 1832 and struck again in 1848 and 1854.<ref name=air/> [[Typhus]] and [[tuberculosis]] were also common in the crowded 19th century tenements. The {{SS|Princess Alice|1865|2}} was a passenger [[steam ship|steamer]] crowded with day trippers returning from [[Gravesend, Kent|Gravesend]] to [[Woolwich]] and [[London Bridge]]. On the evening of 3 September 1878, she collided with the steam [[Collier (ship)|collier]] ''Bywell Castle'' (named for [[Bywell Castle]]) and sank into the [[Thames]] in under four minutes. Of the approximately 700 passengers, over 600 were lost.<ref>[http://www.thamespolicemuseum.org.uk/h_alice_1.html ''Princess Alice Disaster''] Thames Police Museum accessed 19 September 2007</ref> |

Many disasters have befallen the residents of the East End, both in war and in peace. In particular, as a maritime port, [[Plague (disease)|plague]] and pestilence have disproportionately fallen on the residents of the East End. The area most afflicted by the [[Great Plague of London|Great Plague (1665)]] was Spitalfields,<ref>Plague deaths measured at more than 3000 deaths per 478 sq yards in Spitalfields in 1665 (source: ''London from the Air'')</ref> and cholera epidemics broke out in Limehouse in 1832 and struck again in 1848 and 1854.<ref name=air/> [[Typhus]] and [[tuberculosis]] were also common in the crowded 19th century tenements. The {{SS|Princess Alice|1865|2}} was a passenger [[steam ship|steamer]] crowded with day trippers returning from [[Gravesend, Kent|Gravesend]] to [[Woolwich]] and [[London Bridge]]. On the evening of 3 September 1878, she collided with the steam [[Collier (ship)|collier]] ''Bywell Castle'' (named for [[Bywell Castle]]) and sank into the [[Thames]] in under four minutes. Of the approximately 700 passengers, over 600 were lost.<ref>[http://www.thamespolicemuseum.org.uk/h_alice_1.html ''Princess Alice Disaster''] Thames Police Museum accessed 19 September 2007</ref> |

||

During the First World War, the morning of 13 June 1917 was the first ever daylight air-raid over the east end which in total killed 104 people. Sixteen of the dead were 5 and 6 year olds who were sitting in their class room at Upper North Street School, Poplar when the bomb hit. The memorial which still stands today in Poplar Recreation Ground was built by [[A.R. Adams Funeral Directors|A.R. Adams]], a local funeral director at the time. Also, on 19 January 1917, 73 people died, including 14 workers, and more than 400 were injured, in a [[Silvertown explosion|TNT explosion]] in the Brunner-Mond munitions factory in [[Silvertown]]. Much of the area was flattened, and the shock wave was felt throughout the city and much of [[Essex]]. This was the largest explosion in London history, and was heard in [[Southampton]] and [[Norwich]]. Andreas Angel, chief chemist at the plant, was posthumously awarded the [[Edward Medal]] for trying to extinguish the fire that caused the blast.<ref>''The Silvertown Explosion: London 1917'' Graham Hill and Howard Bloch (Stroud: Tempus Publishing 2003). ISBN 0-7524-3053-X.</ref> The same year, on 13 June, a bomb from a German [[Gotha G|Gotha]] bomber killed 18 children in their primary school in Upper North Street, [[Poplar, London|Poplar]]. This event is commemorated by the local war memorial erected in Poplar Recreation Ground,<ref>The ''Poplar War Memorial'' is an exclusively civilian memorial, reflecting the pacifism of the Mayor [[Will Crooks]] and local MP [[George Lansbury]].</ref><ref>[http://www.ppu.org.uk/memorial/children/index.html ''East London in Mourning''] (Peace Pledge Union) accessed 2 April 2007</ref> but during the war a total of 120 children and 104 adults were killed in the East End by aerial bombing, with many more injured.<ref>[http://www.eastlondonhistory.com/east%20end%20at%20war.htm ''The East End at War''] |

During the First World War, the morning of 13 June 1917 was the first ever daylight air-raid over the east end which in total killed 104 people. Sixteen of the dead were 5 and 6 year olds who were sitting in their class room at Upper North Street School, Poplar when the bomb hit. The memorial which still stands today in Poplar Recreation Ground was built by [[A.R. Adams Funeral Directors|A.R. Adams]], a local funeral director at the time. Also, on 19 January 1917, 73 people died, including 14 workers, and more than 400 were injured, in a [[Silvertown explosion|TNT explosion]] in the Brunner-Mond munitions factory in [[Silvertown]]. Much of the area was flattened, and the shock wave was felt throughout the city and much of [[Essex]]. This was the largest explosion in London history, and was heard in [[Southampton]] and [[Norwich]]. Andreas Angel, chief chemist at the plant, was posthumously awarded the [[Edward Medal]] for trying to extinguish the fire that caused the blast.<ref>''The Silvertown Explosion: London 1917'' Graham Hill and Howard Bloch (Stroud: Tempus Publishing 2003). ISBN 0-7524-3053-X.</ref> The same year, on 13 June, a bomb from a German [[Gotha G|Gotha]] bomber killed 18 children in their primary school in Upper North Street, [[Poplar, London|Poplar]]. This event is commemorated by the local war memorial erected in Poplar Recreation Ground,<ref>The ''Poplar War Memorial'' is an exclusively civilian memorial, reflecting the pacifism of the Mayor [[Will Crooks]] and local MP [[George Lansbury]].</ref><ref>[http://www.ppu.org.uk/memorial/children/index.html ''East London in Mourning''] (Peace Pledge Union) accessed 2 April 2007</ref> but during the war a total of 120 children and 104 adults were killed in the East End by aerial bombing, with many more injured.<ref>[http://www.eastlondonhistory.com/east%20end%20at%20war.htm ''The East End at War''] East London History Society accessed 14 November 2007 {{wayback|url=http://www.eastlondonhistory.com/east%20end%20at%20war.htm |date=20071219182742 |df=y }}</ref> |

||

Another tragedy occurred on the morning of 16 May 1968 when [[Ronan Point]], a 23-storey [[tower block]] in [[London Borough of Newham|Newham]], suffered a structural collapse due to a [[natural gas]] explosion. Four people were killed in the disaster and seventeen were injured, as an entire corner of the building slid away. The collapse caused major changes in UK building regulations and led to the decline of further building of high rise [[council flats]] that had characterised 1960s public architecture.<ref>''Collapse: Why Buildings Fall Down'' Phil Wearne (Channel 4 books) ISBN 0-7522-1817-4</ref> |

Another tragedy occurred on the morning of 16 May 1968 when [[Ronan Point]], a 23-storey [[tower block]] in [[London Borough of Newham|Newham]], suffered a structural collapse due to a [[natural gas]] explosion. Four people were killed in the disaster and seventeen were injured, as an entire corner of the building slid away. The collapse caused major changes in UK building regulations and led to the decline of further building of high rise [[council flats]] that had characterised 1960s public architecture.<ref>''Collapse: Why Buildings Fall Down'' Phil Wearne (Channel 4 books) ISBN 0-7522-1817-4</ref> |

||

| Line 213: | Line 213: | ||

The music hall tradition of live entertainment lingers on in East End public houses, with music and singing. This is complemented by less respectable amusements such as [[striptease]], which, since the 1950s has become a fixture of certain East End pubs, particularly in the area of [[Shoreditch]], despite being a target of local authority restraints.<ref>Lara Clifton ''Baby Oil and Ice: Striptease in East London'' (DoNotPress, 2002) ISBN 1-899344-85-3</ref> |

The music hall tradition of live entertainment lingers on in East End public houses, with music and singing. This is complemented by less respectable amusements such as [[striptease]], which, since the 1950s has become a fixture of certain East End pubs, particularly in the area of [[Shoreditch]], despite being a target of local authority restraints.<ref>Lara Clifton ''Baby Oil and Ice: Striptease in East London'' (DoNotPress, 2002) ISBN 1-899344-85-3</ref> |

||

[[File:Hoxton Hall.JPG|thumb|upright|[[Hoxton Hall]], still an active community resource and performance space]] |

[[File:Hoxton Hall.JPG|thumb|upright|[[Hoxton Hall]], still an active community resource and performance space]] |

||

Novelist and social commentator [[Walter Besant]] proposed a 'Palace of Delight'<ref>In [[Walter Besant]] ''All Sorts and Conditions of Men'' (1882)</ref> with concert halls, reading rooms, picture galleries, an art school and various classes, social rooms and frequent fêtes and dances. This coincided with a project by the philanthropist businessman, Edmund Hay Currie to use the money from the winding up of the 'Beaumont Trust',<ref>In 1841, [[John Barber Beaumont]] died and left property in Beaumont Square, Stepney to provide for the 'education and entertainment' of people from the neighbourhood. The charity – and its property – was becoming moribund by the 1870s, and in 1878 it was wound up by the [[Charity Commission]]ers, providing its new chair, Sir Edmund Hay Currie, with £120,000 to invest in a similar project. He raised a further £50,000 and secured continued funding from the Draper's Company for ten years (The Whitechapel Society, below)</ref> together with subscriptions to build a 'People's Palace' in the East End. Five acres of land were secured on the Mile End Road, and the ''Queen's Hall'' was opened by [[Queen Victoria]] on 14 May 1887. The complex was completed with a library, swimming pool, gymnasium and winter garden, by 1892, providing an eclectic mix of populist entertainment and education. A peak of 8000 'tickets' were sold for classes in 1892, and by 1900, a [[Bachelor of Science]] degree awarded by the [[University of London]] was introduced.<ref>''From Palace to College – An illustrated account of Queen Mary College'' G. P. Moss and M. V. Saville pp. 39-48 (University of London 1985) ISBN 0-902238-06-X</ref> In 1931, the building was destroyed by fire, but the [[Worshipful Company of Drapers|Draper's Company]], major donors to the original scheme, invested more to rebuild the technical college and create [[Queen Mary, University of London|Queen Mary's College]] in December 1934.<ref>[http://www.whitechapelsociety.com/London/life_leisure/peoples_palace.htm ''The People's Palace''] |

Novelist and social commentator [[Walter Besant]] proposed a 'Palace of Delight'<ref>In [[Walter Besant]] ''All Sorts and Conditions of Men'' (1882)</ref> with concert halls, reading rooms, picture galleries, an art school and various classes, social rooms and frequent fêtes and dances. This coincided with a project by the philanthropist businessman, Edmund Hay Currie to use the money from the winding up of the 'Beaumont Trust',<ref>In 1841, [[John Barber Beaumont]] died and left property in Beaumont Square, Stepney to provide for the 'education and entertainment' of people from the neighbourhood. The charity – and its property – was becoming moribund by the 1870s, and in 1878 it was wound up by the [[Charity Commission]]ers, providing its new chair, Sir Edmund Hay Currie, with £120,000 to invest in a similar project. He raised a further £50,000 and secured continued funding from the Draper's Company for ten years (The Whitechapel Society, below)</ref> together with subscriptions to build a 'People's Palace' in the East End. Five acres of land were secured on the Mile End Road, and the ''Queen's Hall'' was opened by [[Queen Victoria]] on 14 May 1887. The complex was completed with a library, swimming pool, gymnasium and winter garden, by 1892, providing an eclectic mix of populist entertainment and education. A peak of 8000 'tickets' were sold for classes in 1892, and by 1900, a [[Bachelor of Science]] degree awarded by the [[University of London]] was introduced.<ref>''From Palace to College – An illustrated account of Queen Mary College'' G. P. Moss and M. V. Saville pp. 39-48 (University of London 1985) ISBN 0-902238-06-X</ref> In 1931, the building was destroyed by fire, but the [[Worshipful Company of Drapers|Draper's Company]], major donors to the original scheme, invested more to rebuild the technical college and create [[Queen Mary, University of London|Queen Mary's College]] in December 1934.<ref>[http://www.whitechapelsociety.com/London/life_leisure/peoples_palace.htm ''The People's Palace''] The Whitechapel Society (2006). Retrieved 5 July 2007 {{wayback|url=http://www.whitechapelsociety.com/London/life_leisure/peoples_palace.htm |date=20071011014206 |df=y }}</ref> A new 'People's Palace' was constructed, in 1937, by the [[Metropolitan Borough of Stepney]], in St Helen's Terrace. This finally closed in 1954.<ref>[http://www.qmul.ac.uk/alumni/alumninetwork/qmandw/qm_origins_history.pdf ''Origins and History''] [[Queen Mary, University of London]] Alumni Booklet (2005) accessed 5 July 2007</ref> |

||

Professional theatre returned briefly to the East End in 1972, with the formation of the [[Half Moon Theatre]] in a rented former synagogue in Aldgate. In 1979, they moved to a former [[Methodist]] chapel, near [[Stepney Green]] and built a new theatre on the site, opening in May 1985, with a production of ''[[Sweeney Todd]]''. The theatre enjoyed success, with premières by [[Dario Fo]], [[Edward Bond]] and [[Steven Berkoff]], but by the mid-1980s, the theatre suffered a financial crisis and closed. After years of disuse, it has been converted to a public house.<ref name=hollow>[http://www.aim25.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search2?coll_id=7092&inst_id=11 Royal Holloway ''Half Moon Theatre archive''] Archives in M25. Retrieved 23 October 2007</ref> The theatre spawned two further arts projects: the ''Half Moon Photography Workshop'', exhibiting in the theatre and locally, and from 1976 publishing ''Camerwork'',<ref>[http://photography.about.com/library/weekly/aa112000d.htm British Photography 1945-80: Part 4: Britain in the 70s] |

Professional theatre returned briefly to the East End in 1972, with the formation of the [[Half Moon Theatre]] in a rented former synagogue in Aldgate. In 1979, they moved to a former [[Methodist]] chapel, near [[Stepney Green]] and built a new theatre on the site, opening in May 1985, with a production of ''[[Sweeney Todd]]''. The theatre enjoyed success, with premières by [[Dario Fo]], [[Edward Bond]] and [[Steven Berkoff]], but by the mid-1980s, the theatre suffered a financial crisis and closed. After years of disuse, it has been converted to a public house.<ref name=hollow>[http://www.aim25.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search2?coll_id=7092&inst_id=11 Royal Holloway ''Half Moon Theatre archive''] Archives in M25. Retrieved 23 October 2007</ref> The theatre spawned two further arts projects: the ''Half Moon Photography Workshop'', exhibiting in the theatre and locally, and from 1976 publishing ''Camerwork'',<ref>[http://photography.about.com/library/weekly/aa112000d.htm British Photography 1945-80: Part 4: Britain in the 70s] ''[[The New York Times]]'' online. Retrieved 23 May 2007 {{wayback|url=http://photography.about.com/library/weekly/aa112000d.htm |date=20070126051950 |df=y }}</ref> and the 'Half Moon Young People's Theatre', which remains active in Tower Hamlets.<ref>[http://www.halfmoon.org.uk/aboutus.html ''About Us''] Half Moon Young People's Theatre accessed 23 October 2007</ref> |

||

The football team followed by many East End people is [[West Ham United]], founded in 1895 as Thames Ironworks. The 'other' East London clubs are [[Leyton Orient]], and to a lesser extent [[Dagenham and Redbridge]], but rather than rivalry, there is some overlap of support. [[Millwall F.C.]] originally played in the [[Millwall|area of that name]] on the Isle of Dogs, but moved south of the Thames in 1910. |

The football team followed by many East End people is [[West Ham United]], founded in 1895 as Thames Ironworks. The 'other' East London clubs are [[Leyton Orient]], and to a lesser extent [[Dagenham and Redbridge]], but rather than rivalry, there is some overlap of support. [[Millwall F.C.]] originally played in the [[Millwall|area of that name]] on the Isle of Dogs, but moved south of the Thames in 1910. |

||

Revision as of 20:47, 26 January 2016

The East End of London, also known simply as the East End, is an area of London, England, east of the Roman and medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames. Although not defined by universally accepted formal boundaries, the River Lea can be considered another boundary.[1] For the purposes of his book, East End Past, Richard Tames regards the area as coterminous with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets: however, he acknowledges that this narrow definition excludes parts of southern Hackney, such as Shoreditch and Hoxton, which many would regard as belonging to the East End.[2] Others again, such as Alan Palmer, would extend the area across the Lea to include parts of the London Borough of Newham;[3] while parts of the London Borough of Waltham Forest and London Borough of Hackney are also sometimes included. It is universally agreed, however, that the East End is to be distinguished from East London, which covers a much wider area.

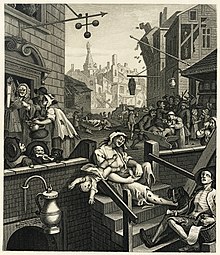

Use of the term East End in a pejorative sense began in the late 19th century,[4] as the expansion of the population of London led to extreme overcrowding throughout the area and a concentration of poor people and immigrants.[5] The problems were exacerbated with the construction of St Katharine Docks (1827)[6] and the central London railway termini (1840–1875) that caused the clearance of former slums and rookeries, with many of the displaced people moving into the East End. Over the course of a century, the East End became synonymous with poverty, overcrowding, disease and criminality.[3]

The East End developed rapidly during the 19th century. Originally it was an area characterised by villages clustered around the City walls or along the main roads, surrounded by farmland, with marshes and small communities by the River, serving the needs of shipping and the Royal Navy. Until the arrival of formal docks, shipping was required to land its goods in the Pool of London, but industries related to construction, repair, and victualling of ships flourished in the area from Tudor times. The area attracted large numbers of rural people looking for employment. Successive waves of foreign immigration began with Huguenot refugees creating a new extramural suburb in Spitalfields in the 17th century.[7] They were followed by Irish weavers,[8] Ashkenazi Jews[9] and, in the 20th century, Bangladeshis.[10] Many of these immigrants worked in the clothing industry. The abundance of semi- and unskilled labour led to low wages and poor conditions throughout the East End. This brought the attentions of social reformers during the mid-18th century and led to the formation of unions and workers associations at the end of the century. The radicalism of the East End contributed to the formation of the Labour Party, and Sylvia Pankhurst based campaigns for women's votes in the area and organised the first Communist Party in England here.

Official attempts to address the overcrowded housing began at the beginning of the 20th century under the London County Council. The Second World War devastated much of the East End, with its docks, railways and industry forming a continual target for bombing, especially during the Blitz, leading to dispersal of the population to new suburbs and new housing being built in the 1950s.[3] The closure of the last of the East End docks in the Port of London in 1980 created further challenges and led to attempts at regeneration and the formation of the London Docklands Development Corporation. The Canary Wharf development, improved infrastructure, and the Olympic Park[11] mean that the East End is undergoing further change, but some parts continue to contain some of the worst poverty in Britain.[12]

Origin and scope

The term 'East End' was first applied to the districts immediately to the east of, and entirely outside, the medieval walled City of London and north of the River Thames; these included Whitechapel and Stepney.

The East End began with the medieval growth of London beyond the walls, mainly along the Roman Roads leading from Bishopsgate and Aldgate.

Growth was much slower in the east, and the modest extensions on this side were separated from the much larger extensions in the west by the marshy open area of Moorfields adjacent to the wall on the north side which discouraged development in that direction.

Building accelerated in the 1500s and the area that would later become known East End began to take shape.

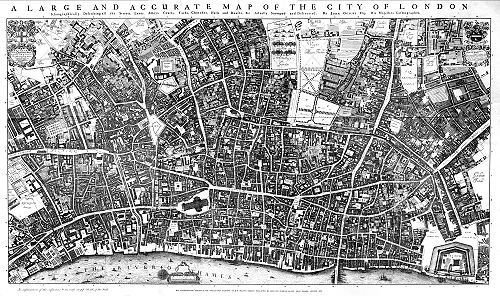

In 1720 John Strype gives us our first record of the East End as a distinct entity when he describes London as consisting of four parts: The City of London, Westminster, Southwark and "That Part Beyond the Tower".

Moorfields wasn't developed until 1777-1812 and the longstanding presence of that open space separating the east and west urban expansions of London must have helped shape the varying economic character of the two parts and perceptions of their distinct identity (see map below).

By the late 19th century, the East End roughly corresponded to the Tower division of Middlesex, which from 1900 formed the metropolitan boroughs of Stepney, Bethnal Green, Poplar and Shoreditch in the County of London. Today it corresponds to the London Borough of Tower Hamlets and the southern part of Hackney.[3]

[The] invention about 1880 of the term 'East End' was rapidly taken up by the new halfpenny press, and in the pulpit and the music hall ... A shabby man from Paddington, St Marylebone or Battersea might pass muster as one of the respectable poor. But the same man coming from Bethnal Green, Shadwell or Wapping was an 'East Ender', the box of Keating's bug powder must be reached for, and the spoons locked up. In the long run this cruel stigma came to do good. It was a final incentive to the poorest to get out of the 'East End' at all costs, and it became a concentrated reminder to the public conscience that nothing to be found in the 'East End' should be tolerated in a Christian country.

— The Nineteenth Century XXIV (1888), [13]

Parts of the London boroughs of Newham and Waltham Forest, formerly in an area of Essex known as 'London over the border', are sometimes considered to be in the East End.[14] However, the River Lea is usually considered to be the eastern boundary of the East End[1] and this definition would exclude the boroughs, but place them in east London.[15] This extension of the term further east is due to the 'diaspora' of East Enders who moved to West Ham about 1886[16] and East Ham about 1894[17] to service the new docks and industries established there. In the inter-war period, migration occurred to new estates built to alleviate conditions in the East End, in particular at Becontree and Harold Hill, or out of London entirely.

The extent of the East End has always been difficult to define. When Jack London came to London in 1902 his Hackney carriage driver did not know the way and he observed, "Thomas Cook and Son, path-finders and trail-clearers, living sign-posts to all the World.... knew not the way to the East End".[18]

Many East Enders are 'Cockneys', although this term has both a geographic and a linguistic connotation. A traditional definition is that to be a Cockney, one had to be born within the sound of Bow Bells, situated in Cheapside. In general, the sound pattern would cover most of the City, and parts of the near East End such as Aldgate and Whitechapel, but it is unlikely that the bells would have been heard in the docklands. In practice, with Royal London the only maternal hospital nearby, today few would be born in the area.

Its linguistic use is more identifiable, with lexical borrowings from Yiddish, Romani, and costermonger slang, and a distinctive accent that features T-glottalization, a loss of dental fricatives and diphthong alterations, amongst others. The accent is said to be a remnant of early English London speech, modified by the many immigrants to the area.[19] The Cockney accent has suffered a long decline, beginning with the introduction in the 20th century of received pronunciation, and the more recent adoption of Estuary English, which itself contains many features of Cockney English.[20]

History

The East End came into being as the separate villages east of London spread and the fields between them were built upon, a process that occurred in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. From the beginning, the East End has always contained some of the poorest areas of London. The main reasons for this include the following:

- the medieval system of copyhold, which prevailed throughout the East End, into the 19th century. Essentially, there was little point in developing land that was held on short leases.[3]

- the siting of noxious industries, such as tanning and fulling downwind outside the boundaries of the City, and therefore beyond complaints and official controls. The foul-smelling industries partially preferred the East End because the prevailing winds in London traveled from west to east (i.e. it was downwind from the rest of the city), meaning that most odors from their businesses would not go into the city but outside, and thereby reduced complaints.

- the low paid employment in the docks and related industries, made worse by the trade practices of outwork, piecework and casual labour.

- and the concentration of the ruling court and national political epicentre in Westminster, on the opposite western side of the City of London.

Historically, the East End is conterminous with the Manor of Stepney. This manor was held by the Bishop of London, in compensation for his duties in maintaining and garrisoning the Tower of London. Further ecclesiastic holdings came about from the need to enclose the marshes and create flood defences along the Thames. Edward VI passed the land to the Wentworth family, and thence to their descendants, the Earls of Cleveland. The ecclesiastic system of copyhold, whereby land was leased to tenants for terms as short as seven years, prevailed throughout the manor. This severely limited scope for improvement of the land and new building until the estate was broken up in the 19th century.[21]

In medieval times trades were carried out in workshops in and around the owners' premises in the City. By the time of the Great Fire these were becoming industries and some were particularly noisome, such as the processing of urine to perform tanning; or required large amounts of space, such as drying clothes after process and dying in fields known as tentergrounds; and rope making. Some were dangerous, such as the manufacture of gunpowder or the proving of guns. These activities came to be performed outside the City walls in the near suburbs of the East End. Later when lead making and bone processing for soap and china came to be established, they too located in the East End rather than the crowded streets of the City.[3]

The lands to the east of the City had always been used as hunting grounds for bishops and royalty, with King John establishing a palace at Bow. The Cistercian Stratford Langthorne Abbey became the court of Henry III in 1267 for the visitation of the Papal legates, and it was here that he made peace with the barons under the terms of the Dictum of Kenilworth. It became the fifth largest Abbey in the country, visited by monarchs and providing a popular retreat (and final resting place) for the nobility.[22] The Palace of Placentia at Greenwich, to the south of the river, was built by the Regent to Henry V, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester and Henry VIII established a hunting lodge at Bromley Hall.[23] These Royal connections continued until after the Interregnum when the Court established itself in the Palace of Whitehall and the offices of politics congregated around them. The East End also lay on the main road to Barking Abbey, important as a religious centre since Norman times and where William the Conqueror had first established his English court.[24]

Politics and social reform

At the end of the 17th century large numbers of Huguenot weavers arrived in the East End, settling to service an industry that grew up around the new estate at Spitalfields, where master weavers were based. They brought with them a tradition of 'reading clubs', where books were read, often in public houses. The authorities were suspicious of immigrants meeting and in some ways they were right to be as these grew into workers' associations and political organisations. Towards the middle of the 18th century the silk industry fell into a decline – partly due to the introduction of printed calico cloth – and riots ensued. These 'Spitalfield Riots' of 1769 were actually centred to the east and were put down with considerable force, culminating in two men being hanged in front of the Salmon and Ball public house at Bethnal Green. One was John Doyle (an Irish weaver), the other John Valline (of Huguenot descent).[25]

In 1844, "An Association for promoting Cleanliness among the Poor" was established, and it built a bath-house and laundry in Glasshouse Yard, East Smithfield. This cost a single penny for bathing or washing and by June 1847 was receiving 4,284 people a year. This led to an Act of Parliament to encourage other municipalities to build their own and the model spread quickly throughout the East End. Timbs noted that "... so strong was the love of cleanliness thus encouraged that women often toiled to wash their own and their children's clothing, who had been compelled to sell their hair to purchase food to satisfy the cravings of hunger".[26]

William Booth began his 'Christian Revival Society' in 1865, preaching the gospel in a tent erected in the 'Friends Burial Ground', Thomas Street, Whitechapel. Others joined his 'Christian Mission', and on 7 August 1878 the Salvation Army was formed at a meeting held at 272 Whitechapel Road.[27] A statue commemorates both his mission and his work in helping the poor. Dubliner Thomas John Barnardo came to the London Hospital, Whitechapel to train for medical missionary work in China. Soon after his arrival in 1866 a cholera epidemic swept the East End killing 3,000 people. Many families were left destitute, with thousands of children orphaned and forced to beg or find work in the factories. In 1867, Barnardo set up a Ragged School to provide a basic education but was shown the many children sleeping rough. His first home for boys was established at 18 Stepney Causeway in 1870. When a boy died after being turned away (the home was full), the policy was instituted that 'No Destitute Child Ever Refused Admission'.[28]

In 1884, the Settlement movement was founded, with settlements such as Toynbee Hall[29] and Oxford House, to encourage university students to live and work in the slums, experience the conditions and try to alleviate some of the poverty and misery in the East End. Notable residents of Toynbee Hall included R. H. Tawney, Clement Attlee, Guglielmo Marconi, and William Beveridge. The Hall continues to exert considerable influence, with the Workers Educational Association (1903), Citizens Advice Bureau (1949) and Child Poverty Action Group (1965) all being founded or influenced by it.[30] In 1888, the matchgirls of Bryant and May in Bow went on strike for better working conditions. This, combined with the many dock strikes in the same era, made the East End a key element in the foundation of modern socialist and trade union organisations, as well as the Suffragette movement.[31]

Towards the end of the 19th century, a new wave of radicalism came to the East End, arriving both with Jewish émigrés fleeing from Eastern European persecution, and Russian and German radicals avoiding arrest. A German émigré anarchist, Rudolf Rocker, began writing in Yiddish for Arbayter Fraynd (Workers' Friend). By 1912, he had organised a mass London garment workers' strike for better conditions and an end to 'sweating'.[32] Amongst the Russians was fellow anarchist Peter Kropotkin who helped found the Freedom Press in Whitechapel. Afanasy Matushenko, one of the leaders of the Potemkin mutiny, fled the failure of the Russian Revolution of 1905 to seek sanctuary in Stepney Green.[33] Leon Trotsky and Vladimir Lenin attended meetings of the newspaper Iskra in 1903. in Whitechapel; and in 1907 Lenin and Joseph Stalin[34][35] attended the Fifth Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party held in a Hoxton church. That congress consolidated the leadership of Lenin's Bolshevik faction and debated strategy for the communist revolution in Russia.[36] Trotsky noted, in his memoires, meeting Maxim Gorky and Rosa Luxemburg at the conference.[37]

By the 1880s, the casual system caused Dock workers to unionise under Ben Tillett and John Burns.[38] This led to a demand for '6d per hour' (The Docker's Tanner),[39] and an end to casual labour in the docks.[40] Colonel G. R. Birt, the general manager at Millwall Docks, gave evidence to a Parliamentary committee, on the physical condition of the workers:

The poor fellows are miserably clad, scarcely with a boot on their foot, in a most miserable state.... These are men who come to work in our docks who come on without having a bit of food in their stomachs, perhaps since the previous day; they have worked for an hour and have earned 5d. [2p]; their hunger will not allow them to continue: they take the 5d. in order that they may get food, perhaps the first food they have had for twenty-four hours.

— Col. G. R. Birt, in evidence to the Parliamentary Committee (1889), [40]

These conditions earned dockers much public sympathy, and after a bitter struggle, the London Dock Strike of 1889 was settled with victory for the strikers, and established a national movement for the unionisation of casual workers, as opposed to the craft unions that already existed.

The philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts was active in the East End, alleviating poverty by founding a sewing school for ex-weavers in Spitalfields and building the ornate Columbia Market in Bethnal Green. She helped to inaugurate the London Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, was a keen supporter of the 'Ragged School Union', and operated housing schemes similar to those of the Model Dwellings Companies such as the East End Dwellings Company and the Four Per Cent Industrial Dwellings Company, where investors received a financial return on their philanthropy.[41] Between the 1890s and 1903, when the work was published, the social campaigner Charles Booth instigated an investigation into the life of London poor (based at Toynbee Hall), much of which was centred on the poverty and conditions in the East End.[42] Further investigations were instigated by the 'Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905-09', the Commission found it difficult to agree, beyond that change was necessary and produced separate minority and majority reports. The minority report was the work of Booth with the founders of the London School of Economics Sidney and Beatrice Webb. They advocated focusing on the causes of poverty and the radical notion of poverty being involuntary, rather than the result of innate indolence. At the time their work was rejected but was gradually adopted as policy by successive governments.[43]

Sylvia Pankhurst became increasingly disillusioned with the suffragette movement's inability to engage with the needs of working class women, so in 1912 she formed her own breakaway movement, the East London Federation of Suffragettes. She based it at a baker's shop at Bow emblazoned with the slogan, "Votes for Women", in large gold letters. The local Member of Parliament, George Lansbury, resigned his seat in the House of Commons to stand for election on a platform of women's enfranchisement. Pankhurst supported him in this, and Bow Road became the campaign office, culminating in a huge rally in nearby Victoria Park. Lansbury was narrowly defeated in the election, however, and support for the project in the East End was withdrawn. Pankhurst refocused her efforts, and with the outbreak of the First World War, she began a nursery, clinic and cost price canteen for the poor at the bakery. A paper, the Women's Dreadnought, was published to bring her campaign to a wider audience. Pankhurst spent twelve years in Bow fighting for women's rights. During this time, she risked constant arrest and spent many months in Holloway Prison, often on hunger strike. She finally achieved her aim of full adult female suffrage in 1928, and along the way she alleviated some of the poverty and misery, and improved social conditions for all in the East End.[44]

The alleviation of widespread unemployment and hunger in Poplar had to be funded from money raised by the borough itself under the Poor Law. The poverty of the borough made this patently unfair and lead to the 1921 conflict between government and the local councillors known as the Poplar Rates Rebellion. Council meetings were for a time held in Brixton prison, and the councillors received wide support.[45] Ultimately, this led to the abolition of the Poor Laws through the Local Government Act 1929.

The General Strike had begun as a dispute between miners and their employers outside London in 1925. On 1 May 1926 the Trades Union Congress called out workers all over the country, including the London dockers. The government had had over a year to prepare and deployed troops to break the dockers' picket lines. Armed food convoys, accompanied by armoured cars drove down the East India Dock Road. By 10 May, a meeting was brokered at Toynbee Hall to end the strike. The TUC were forced into a humiliating climbdown and the general strike ended on 11 May, with the miners holding out until November.[46]

Industry and built environment

Industries associated with the sea developed throughout the East End, including rope making and shipbuilding. The former location of roperies can still be identified from their long straight, narrow profile in the modern streets, for instance Ropery Street near Mile End. Shipbuilding was important from the time when Henry VIII caused ships to be built at Rotherhithe as a part of his expansion of the Royal Navy. On 31 January 1858, the largest ship of that time, the SS Great Eastern, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, was launched from the yard of Messrs Scott Russell & Co, of Millwall. The 692-foot (211 m) vessel was too long to fit across the river, and so the ship had to be launched sideways. Due to the technical difficulties of the launch, this was the last big ship to be built on the River, and the industry fell into a long decline.[47] Smaller ships, including battleships, continued to be built at the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company at Blackwall until the beginning of the 20th century.

The West India Docks were established in 1803, providing berths for larger ships and a model for future London dock building. Imported produce from the West Indies was unloaded directly into quayside warehouses. Ships were limited to 6000 tons.[48] The old Brunswick Dock, a shipyard at Blackwall became the basis for the East India Company's East India Docks established there in 1806.[49] The London Docks were built in 1805, and the waste soil and rubble from the construction was carried by barge to west London, to build up the marshy area of Pimlico. These docks imported tobacco, wine, wool and other goods into guarded warehouses within high walls (some of which still remain). They were able to berth over 300 sailing vessels simultaneously, but by 1971 they closed, no longer able to accommodate modern shipping.[50] The most central docks, St Katharine Docks, were built in 1828 to accommodate luxury goods, clearing the slums that lay in the area of the former Hospital of St Katharine. They were not successful commercially, as they were unable to accommodate the largest ships, and in 1864, management of the docks was amalgamated with that of the London Docks.[51] The Millwall Docks were created in 1868, predominantly for the import of grain and timber. These docks housed the first purpose built granary for the Baltic grain market, a local landmark that remained until it was demolished to improve access for the London City Airport.[52]

The first railway ('The Commercial Railway') to be built, in 1840, was a passenger service based on cable haulage by stationary steam engines that ran the 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from Minories to Blackwall on a pair of tracks. It required 14 miles (22.5 km) of hemp rope, and 'dropped' carriages as it arrived at stations, which were reattached to the cable for the return journey, and the train 'reassembling' itself at the terminus.[53] The line was converted to standard gauge in 1859, and steam locomotives adopted. The building of London termini at Fenchurch Street (1841),[54] and Bishopsgate (1840) provided access to new suburbs across the River Lea, again resulting in the destruction of housing and increased overcrowding in the slums. After the opening of Liverpool Street station (1874), Bishopsgate railway station became a goods yard, in 1881, to bring imports from Eastern ports. With the introduction of containerisation, the station declined, suffered a fire in 1964 that destroyed the station buildings, and it was finally demolished in 2004 for the extension of the East London Line. In the 19th century, the area north of Bow Road became a major railway centre for the North London Railway, with marshalling yards and a maintenance depot serving both the City and the West India docks. Nearby Bow railway station opened in 1850 and was rebuilt in 1870 in a grand style, featuring a concert hall. The line and yards closed in 1944, after severe bomb damage, and never reopened, as goods became less significant, and cheaper facilities were concentrated in Essex.[55]

The River Lea was a smaller boundary than the Thames, but it was a significant one. The building of the Royal Docks consisting of the Royal Victoria Dock (1855), able to berth vessels of up to 8000 tons;[56] Royal Albert Dock (1880), up to 12,000 tons;[57] and King George V Dock (1921), up to 30,000 tons,[58] on the estuary marshes, extended the continuous development of London across the Lea into Essex for the first time.[59] The railways gave access to a passenger terminal at Gallions Reach and new suburbs created in West Ham, which quickly became a major manufacturing town, with 30,000 houses built between 1871 and 1901.[16] Soon afterwards, East Ham was built up to serve the new Gas Light and Coke Company and Bazalgette's grand sewage works at Beckton.[17]

From the mid-20th century, the docks declined in use and were finally closed in 1980, leading to the setting up of the London Docklands Development Corporation in 1981.[60] London's main port is now at Tilbury, further down the Thames estuary, outside the boundary of Greater London. The dock had been established in 1886 to bring bulk goods by rail to London, but being nearer the sea and able to accommodate vessels of 50,000 tons, they were more easily converted to the needs of modern container ships in 1968, and so they survived the closure of the inner docks.[61] Various wharves along the river continue in use but on a much smaller scale.

Settlement

During the Middle Ages, settlements had been established predominantly along the lines of the existing roads, and the principal villages were Stepney, Whitechapel and Bow. Settlements along the river began at this time to service the needs of shipping on the Thames, but the City of London retained its right to actually land the goods. The riverside became more active in Tudor times, as the Royal Navy was expanded and international trading developed. Downstream, a major fishing port developed at Barking to provide fish to the City.

Whereas royalty such as King John had had a hunting lodge at Bromley-by-Bow, and the Bishop of London had a palace at Bethnal Green, later these estates began to be split up, and estates of fine houses for captains, merchants and owners of manufacturers began to be built. Samuel Pepys moved his family and goods to Bethnal Green during the Great Fire of London, and Captain Cook moved from Shadwell to Stepney Green, a place where a school and assembly rooms had been established (commemorated by Assembly Passage, and a plaque on the site of Cook's house on the Mile End Road). Mile End Old Town also acquired some fine buildings, and the New Town began to be built. As the area became built up and more crowded, the wealthy sold their plots for sub-division and moved further afield. Into the 18th and 19th centuries, there were still attempts to build fine houses, for example Tredegar Square (1830), and the open fields around Mile End New Town were used for the construction of estates of workers' cottages in 1820. This was designed in 1817 in Birmingham by Anthony Hughes and finally constructed in 1820 [62]

Globe Town was established from 1800 to provide for the expanding population of weavers around Bethnal Green, attracted by improving prospects in silk weaving. The population of Bethnal Green trebled between 1801 and 1831, with 20,000 looms being operated in people's own homes. By 1824, with restrictions on importation of French silks relaxed, up to half these looms had become idle, and prices were driven down. With many importing warehouses already established in the district, the abundance of cheap labour was turned to boot, furniture and clothing manufacture.[5] Globe Town continued its expansion into the 1860s, long after the decline of the silk industry.

During the 19th century, building on an adhoc basis could never keep up with the needs of the expanding population. Henry Mayhew visited Bethnal Green in 1850 and wrote for the Morning Chronicle, as a part of a series forming the basis for London Labour and the London Poor (1851), that the trades in the area included tailors, costermongers, shoemakers, dustmen, sawyers, carpenters, cabinet makers and silkweavers. He noted that in the area:

roads were unmade, often mere alleys, houses small and without foundations, subdivided and often around unpaved courts. An almost total lack of drainage and sewerage was made worse by the ponds formed by the excavation of brickearth. Pigs and cows in back yards, noxious trades like boiling tripe, melting tallow, or preparing cat's meat, and slaughter houses, dustheaps, and 'lakes of putrefying night soil' added to the filth

— Henry Mayhew London Labour and London Poor (1851), [63]

A movement began to clear the slums – with Burdett-Coutts building Columbia Market in 1869 and with the passing of the "Artisans' and Labourers' Dwelling Act" in 1876 to provide powers to seize slums from landlords and provide access to public funds to build new housing.[64] Housing associations such as the Peabody Trust were formed to provide philanthropic homes for the poor and clearing the slums generally. Expansion work by the railway companies, such as the London and Blackwall Railway and Great Eastern Railway, caused large areas of slum housing to be demolished. The "Working Classes Dwellings Act" in 1890 placed a new responsibility to house the displaced residents and this led to the building of new "philanthropic housing" such as Blackwall Buildings and Great Eastern Buildings.[65]

By 1890 official slum clearance programmes had begun. One was the creation of the world's first council housing, the LCC Boundary Estate, which replaced the neglected and crowded streets of Friars Mount, better known as The Old Nichol Street Rookery.[66] Between 1918 and 1939 the LCC continued replacing East End housing with five or six storey flats, despite residents preferring houses with gardens and opposition from shopkeepers who were forced to relocate to new, more expensive premises. The Second World War brought an end to further slum clearance.[67]

Second World War

Hardest of all, the Luftwaffe will smash Stepney. I know the East End! Those dirty Jews and Cockneys will run like rabbits into their holes.

— [68], Germany Calling – Lord Haw-Haw, collaborator and broadcaster

Initially, the German commanders were reluctant to bomb London, fearing retaliation against Berlin. On 24 August 1940, a single aircraft, tasked to bomb Tilbury, accidentally bombed Stepney, Bethnal Green and the City. The following night the RAF retaliated by mounting a forty aircraft raid on Berlin, with a second attack three days later. The Luftwaffe changed its strategy from attacking shipping and airfields to attacking cities. The City and West End were designated 'Target Area B'; the East End and docks were 'Target Area A'. The first raid occurred at 4:30 p.m. on 7 September and consisted of 150 Dornier and Heinkel bombers and large numbers of fighters. This was followed by a second wave of 170 bombers. Silvertown and Canning Town bore the brunt of this first attack.[3]

Between 7 September 1940 and 10 May 1941, a sustained bombing campaign was mounted. It began with the bombing of London for 57 successive nights,[69] an era known as 'the Blitz'. East London was targeted because the area was a centre for imports and storage of raw materials for the war effort, and the German military command felt that support for the war could be damaged among the mainly working class inhabitants. On the first night of the Blitz, 430 civilians were killed and 1,600 seriously wounded.[69] The populace responded by evacuating children and the vulnerable to the country[70] and digging in, constructing Anderson shelters in their gardens and Morrison shelters in their houses, or going to communal shelters built in local public spaces.[71] On 10 September 1940, 73 civilians, including women and children preparing for evacuation, were killed when a bomb hit the South Hallsville School. Although the official death toll is 73,[72] many local people believed it must have been higher. Some estimates say 400 or even 600 may have lost their lives during this raid on Canning Town.[73]

The effect of the intensive bombing worried the authorities and 'Mass-Observation' was deployed to gauge attitudes and provide policy suggestions,[74] as before the war they had investigated local attitudes to anti-Semitism.[75] The organisation noted that close family and friendship links within the East End were providing the population with a surprising resilience under fire. Propaganda was issued, reinforcing the image of the 'brave chirpy Cockney'. On the Sunday after the Blitz began, Winston Churchill himself toured the bombed areas of Stepney and Poplar. Anti-aircraft installations were built in public parks, such as Victoria Park and the Mudchute on the Isle of Dogs, and along the line of the Thames, as this was used by the aircraft to guide them to their target.

The authorities were initially wary of opening the London Underground for shelter, fearing the effect on morale elsewhere in London and hampering normal operations. On 12 September, having suffered five days of heavy bombing, the people of the East End took the matter into their own hands and invaded tube stations with pillows and blankets. The government relented and opened the partially completed Central line as a shelter. Many deep tube stations remained in use as shelters until the end of the war.[3] Aerial mines were deployed on 19 September 1940. These exploded at roof top height, causing severe damage to buildings over a wider radius than the impact bombs. By now, the Port of London had sustained heavy damage with a third of its warehouses destroyed, and the West India and St Katherine Docks had been badly hit and put out of action. Bizarre events occurred when the River Lea burned with an eerie blue flame, caused by a hit on a gin factory at Three Mills, and the Thames itself burnt fiercely when Tate & Lyle's Silvertown sugar refinery was hit.[3]

On 3 March 1943 at 8:27 p.m., the unopened Bethnal Green tube station was the site of a wartime disaster. Families had crowded into the underground station due to an air-raid siren at 8:17, one of 10 that day. There was a panic at 8:27 coinciding with the sound of an anti-aircraft battery (possibly the recently installed Z battery) being fired at nearby Victoria Park. In the wet, dark conditions, a woman slipped on the entrance stairs and 173 people died in the resulting crush. The truth was suppressed, and a report appeared that there had been a direct hit by a German bomb. The results of the official investigation were not released until 1946.[76] There is now a plaque at the entrance to the tube station, which commemorates the event as the "worst civilian disaster of World War II". The first V-1 flying bomb struck in Grove Road, Mile End, on 13 June 1944, killing six, injuring 30, and making 200 people homeless.[62] The area remained derelict for many years until it was cleared to extend Mile End Park. Before demolition, local artist Rachel Whiteread made a cast of the inside of 193 Grove Road. Despite attracting controversy, the exhibit won her the Turner Prize for 1993.[77]

It is estimated that by the end of the war, 80 tons of bombs had fallen on the Metropolitan Borough of Bethnal Green alone, affecting 21,700 houses, destroying 2,233 and making a further 893 uninhabitable. In Bethnal Green, 555 people were killed, and 400 were seriously injured.[67] For the whole of Tower Hamlets, a total of 2,221 civilians were killed, and 7,472 were injured, with 46,482 houses destroyed and 47,574 damaged.[78] So badly battered was the East End that when Buckingham Palace was hit during the height of the bombing, Queen Elizabeth observed that "It makes me feel I can look the East End in the face."[79][80] By the end of the war, the East End was a scene of devastation, with large areas derelict and depopulated. War production was changed quickly to making prefabricated housing,[81] and many were installed in the bombed areas and remained common into the 1970s. Today, 1950s and 1960s architecture dominates the housing estates of the area such as the Lansbury Estate in Poplar, much of which was built as a show-piece of the 1951 Festival of Britain.[82]

Population

Throughout history the area has absorbed waves of immigrants, who have each added a new dimension to the culture and history of the area, most notably the French Protestant Huguenots in the 17th century,[7] the Irish in the 18th century,[8] Ashkenazi Jews fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe towards the end of the 19th century,[9] and the Bangladeshi[10] community settling in the East End from the 1960s.

Immigration

Immigrant communities first developed in the riverside settlements. From the Tudor era until the 20th century, ships' crews were employed on a casual basis. New and replacement crew would be found wherever they were available, local sailors being particularly prized for their knowledge of currents and hazards in foreign ports. Crews would be paid off at the end of their voyage. Inevitably, permanent communities became established, including colonies of Lascars and Africans from the Guinea Coast. Large Chinatowns at both Shadwell and Limehouse developed, associated with the crews of merchantmen in the opium and tea trades. It was only after the devastation of the Second World War that this predominantly Han Chinese community relocated to Soho.[84]

In 1786, the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor was formed by citizens concerned at the size of London's indigent Black population, many of whom had been expelled from North America as Black Loyalists — former slaves who had fought on the side of the British in the War of Independence. Others were discharged sailors and some a legacy of British involvement in the slave trade. The committee distributed food, clothing, medical aid and found work for men, from various locations including the White Raven tavern in Mile End.[85] They also helped the men to go abroad, some to Canada. In October 1786, the Committee funded an ill-fated expedition of 280 black men, 40 black women and 70 white women (mainly wives and girlfriends) to settle in Sierra Leone.[86] From the late 19th century, a large African mariner community was established in Canning Town as a result of new shipping links to the Caribbean and West Africa.[87]

Immigrants have not always been readily accepted and in 1517 the Evil May Day riots, where foreign-owned property was attacked, resulted in the deaths of 135 Flemings in Stepney. The Gordon Riots of 1780 began with burnings of the houses of Catholics and their chapels in Poplar and Spitalfields.[88]

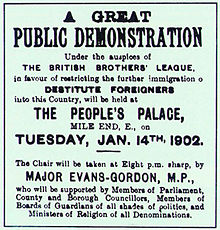

In the 1870 and 80s, so many Jewish émigrés were arriving that over 150 synagogues were built. Today there are only four active synagogues remaining in Tower Hamlets: the Congregation of Jacob Synagogue (1903 – Kehillas Ya'akov), the East London Central Synagogue (1922), the Fieldgate Street Great Synagogue (1899) and Sandys Row Synagogue (1766).[89] Jewish immigration to the East End peaked in the 1890s, leading to anti-foreigner agitation by the British Brothers League, formed in 1902 by Captain William Stanley Shaw and the Conservative MP for Stepney, Major Evans-Gordon, who had overturned a Liberal majority in the 1900 General Election on a platform of limiting immigration. In Parliament in 1902, Evans-Gordon claimed that "not a day passes but English families are ruthlessly turned out to make room for foreign invaders. The rates are burdened with the education of thousands of foreign children."[90] Jewish immigration only slowed with the passing of the Aliens Act 1905, which gave the Home Secretary powers to regulate and control immigration.[91]

At the beginning of the 20th century, London was the capital of the extensive British Empire, which contained tens of millions of Muslims, but had no mosque for Muslim residents or visitors. On 9 November 1910, at a meeting of Muslims and non-Muslims at the Ritz Hotel, the London Mosque Fund was established with the aims of organising weekly Friday prayers and providing a permanent place of worship for Muslims in London.[92] From 1910 to 1940 various rooms had been hired for Jumu'ah prayers on Fridays. Finally, in 1940, three houses were purchased at 446–448 Commercial Road in the East End of London as a permanent place of prayer. On 2 August 1941 the combined houses were inaugurated as the 'East London Mosque and Islamic Culture Centre' at a ceremony attended by the Egyptian Ambassador, Colonel Sir Gordon Neal (representing the Secretary of State for India). The first prayer was led by the Ambassador for Saudi Arabia, Shaikh Hafiz Wahba.[93] From the late 1950s the local Muslim population began to increase due to further immigration from the Indian subcontinent, particularly from Sylhet in East Pakistan, which became Bangladesh in 1971. The migrants settled in areas already established by the Sylheti expatriate community, working in the local docks and Jewish tailoring shops set up in the days of British India.[94] During the 1970s, this immigration increased significantly. In 1975 the local authority bought the properties in Commercial Road under a compulsory purchase order, in return providing a site with temporary buildings on Whitechapel Road. The local community set about raising funds to erect a purpose-built mosque on the site. King Fahd of Saudi Arabia donated £1.1 million of the £2 million fund,[95] and the governments of Kuwait and Britain also donated to the fund.[96] Seven years later, the building of the new mosque commenced, with foundations laid in 1982 and construction completed in 1985. It was one of the first mosques in the European Union to broadcast the adhan from the minaret using loudspeakers. Currently, the mosque has a capacity of 7,000, with prayer areas for men and women, and classroom space for supplementary education. However, by the 1990s the capacity was already insufficient for the growing congregation and for the range of projects based there.[97]

Community tensions were again raised by an anti-semitic Fascist march that took place in 1936 and was blocked by residents and activists at the Battle of Cable Street.[98] From the mid-1970s anti-Asian violence occurred,[99] culminating in the murder on 4 May 1978 of a 25-year-old clothing worker named Altab Ali by three white teenagers in a racially motivated attack. Bangladeshi groups mobilised for self-defence, 7,000 people marched to Hyde Park in protest, and the community became more politically involved.[100] The former churchyard of St Mary's Whitechapel, near where the attack took place, was renamed "Altab Ali Park" in 1998 as a commemoration of his death. Inter-racial tension has continued with occasional outbreaks of violence and in 1993 there was a council seat win for the British National Party (since lost).[101] A 1999 bombing in Brick Lane was part of a series that targeted ethnic minorities, gays and "multiculturalists".[102]

Demographics

The population of the East End increased inexorably throughout the 19th century. House building could not keep pace and overcrowding was rife. It was not until the interwar period that there was a decline caused by migration to new London suburbs like the Becontree estate, built by the London County Council between 1921 and 1932, and to areas outside London.[103] This depopulation accelerated after the Second World War and has only recently begun to reverse.

These population figures reflect the area that now forms the London Borough of Tower Hamlets only:

| Borough | 1811[104] | 1841[104] | 1871[104] | 1901[105] | 1931[105] | 1961[105] | 1971[106] | 1991 | 2001[107] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bethnal Green | 33,619 | 74,088 | 120,104 | 129,680 | 108,194 | 47,078 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Poplar | 13,548 | 31,122 | 116,376 | 168,882 | 155,089 | 66,604 | |||

| Stepney | 131,606 | 203,802 | 275,467 | 298,600 | 225,238 | 92,000 | |||

| Total | 178,773 | 309,012 | 511,947 | 597,102 | 488,611 | 205,682 | 165,791 | 161,064 | 196,106 |

By comparison, in 1801 the population of England and Wales was 9 million; by 1851 it had more than doubled to 18 million, and by the end of the century had reached 40 million.[62] Today, Bangladeshis form the largest minority population in Tower Hamlets, constituting 33.5% of the borough's population at the 2001 census; the Bangladeshi community there is the largest such community in Britain.[108] The 2006 estimates show a decline in this group to 29.8% of the population, reflecting a movement to better economic circumstances and the larger houses available in the eastern suburbs.[109] In this, the latest group of migrants are following a pattern established for over three centuries.

Crime

The high levels of poverty in the East End have, throughout history, corresponded with a high incidence of crime. From earliest times, crime depended, as did labour, on the importing of goods to London, and their interception in transit. Theft occurred in the river, on the quayside and in transit to the City warehouses. This was why, in the 17th century, the East India Company built high-walled docks at Blackwall and had them guarded to minimise the vulnerability of their cargoes. Armed convoys would then take the goods to the company's secure compound in the City. The practice led to the creation of ever-larger docks throughout the area, and large roads to drive through the crowded 19th century slums to carry goods from the docks.[3]

No police force operated in London before the 1750s. Crime and disorder were dealt with by a system of magistrates and volunteer parish constables, with strictly limited jurisdiction. Salaried constables were introduced by 1792, although they were few in number and their power and jurisdiction continued to derive from local magistrates, who in extremis could be backed by militias. In 1798, England's first Marine Police Force was formed by magistrate Patrick Colquhoun and a Master Mariner, John Harriott, to tackle theft and looting from ships anchored in the Pool of London and the lower reaches of the river. Its base was (and remains) in Wapping High Street. It is now known as the Marine Support Unit.[110]

In 1829, the Metropolitan Police Force was formed, with a remit to patrol within 7 miles (11 km) of Charing Cross, with a force of 1,000 men in 17 divisions, including 'H' division, based in Stepney. Each division was controlled by a superintendent, under whom were four inspectors and sixteen sergeants. The regulations demanded that recruits should be under thirty-five years of age, well built, at least 5-foot-7-inch (1.70 m) in height, literate and of good character.[111]

Unlike the former constables, the police were recruited widely and financed by a levy on ratepayers; so they were initially disliked. The force took until the mid-19th century to be established in the East End. Unusually, Joseph Sadler Thomas, a Metropolitan Police superintendent of 'F' (Covent Garden) Division, appears to have mounted the first local investigation (in Bethnal Green), in November 1830 of the London Burkers.[112] A specific Dockyard division of the Metropolitan force was formed to assume responsibility for shore patrols within the docks in 1841,[113] a detective department was formed in 1842, and in 1865, 'J' division was established in Bethnal Green.[111]

One of the East End industries that serviced ships moored off the Pool of London was prostitution, and in the 17th century, this was centred on the Ratcliffe Highway, a long street lying on the high ground above the riverside settlements. In 1600, it was described by the antiquarian John Stow as 'a continual street, or filthy straight passage, with alleys of small tenements or cottages builded, inhabited by sailors and victuallers.' Crews were 'paid off' at the end of a long voyage, and would spend their earnings on drink in the local taverns.[114]

One madame described as 'the great bawd of the seamen' by Samuel Pepys was Damaris Page. Born in Stepney in approximately 1610, she had moved from prostitution to running brothels, including one on the Highway that catered for ordinary seaman and a further establishment nearby that catered for the more expensive tastes amongst the officers and gentry. She died wealthy, in 1669, in a house on the Highway, despite charges being brought against her and time spent in Newgate Prison.[114][115]

By the 19th century, an attitude of toleration had changed, and the social reformer William Acton described the riverside prostitutes as a 'horde of human tigresses who swarm the pestilent dens by the riverside at Ratcliffe and Shadwell'. The 'Society for the Suppression of Vice' estimated that between the Houndsditch, Whitechapel and Ratcliffe areas there were 1803 prostitutes; and between Mile End, Shadwell and Blackwall 963 women in the trade. They were often victims of circumstance, there being no welfare state and a high mortality rate amongst the inhabitants that left wives and daughters destitute, with no other means of income.[116]

At the same time, religious reformers began to introduce 'Seamans' Missions' throughout the dock areas that sought both to provide for seafarer's physical needs and to keep them away from the temptations of drink and women. Eventually, the passage of the 'Contagious Diseases Act' in 1864 allowed policemen to arrest prostitutes and detain them in hospital. The act was repealed in 1886, after agitation by early feminists, such as Josephine Butler and Elizabeth Wolstenholme, led to the formation of the Ladies National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts.[117]

Notable crimes in the area include the Ratcliff Highway murders (1813);[118] the killings committed by the London Burkers (apparently inspired by Burke and Hare) in Bethnal Green (1831);[119] the notorious serial killings of prostitutes by Jack the Ripper[31] (1888); and the Siege of Sidney Street (1911) (in which anarchists, inspired by the legendary Peter the Painter, took on Home Secretary Winston Churchill, and the army).[120]

In the 1960s the East End was the area most associated with gangster activity, most notably that of the Kray twins.[121] The 1996 Docklands bombing caused significant damage around South Quay Station, to the south of the main Canary Wharf development. Two people were killed and thirty-nine injured in one of Mainland Britain's biggest bomb attacks by the Provisional Irish Republican Army.[122] This led to the introduction of police checkpoints controlling access to the Isle of Dogs, reminiscent of the City's 'ring of steel'.

Disasters