Communications satellite: Difference between revisions

Concertmusic (talk | contribs) →Origins to first artificial satellite: added URL to NASA book reference |

Concertmusic (talk | contribs) →History: moved CMR entry and added production date |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

===Origins to first artificial satellite=== |

===Origins to first artificial satellite=== |

||

The concept of the geostationary communications satellite was first proposed by [[Arthur C. Clarke]], along with [[Mikhail Tikhonravov]] and [[Sergey Korolev]] building on work by [[Konstantin Tsiolkovsky]]. <ref>{{cite web| url= https://www.airspacemag.com/space/the-man-behind-the-curtain-22131111/?all |author= Asif Siddiqi |title= The Man Behind the Curtain|publisher= Air & Space Magazine |date=November 2007|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> In October 1945, Clarke published an article titled "Extraterrestrial Relays" in the British magazine ''[[Wireless World]]''. <ref>{{cite web| url=http://clarkeinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/ClarkeWirelessWorldArticle.pdf |author=Arthur C. Clarke|title= Extraterrestrial Relays: Can Rocket Stations Give World-wide Radio Coverage?|publisher=Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education|date=October 1945|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> The article described the fundamentals behind the deployment of [[satellite|artificial satellite]]s in geostationary orbits for the purpose of relaying radio signals. Thus, Arthur C. Clarke is often quoted as being the [[invention|inventor]] of the concept of the communications satellite, as well as the term 'Clarke Belt' employed as a description of the orbit.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1997/08/03/orbit-wars/d5840c66-d2c4-4682-bd95-5f97d46b8843/ |author=Mike Mills|title=Orbit Wars |publisher=The Washington Post |date=3 August 1997|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

The concept of the geostationary communications satellite was first proposed by [[Arthur C. Clarke]], along with [[Mikhail Tikhonravov]] and [[Sergey Korolev]] building on work by [[Konstantin Tsiolkovsky]]. <ref>{{cite web| url= https://www.airspacemag.com/space/the-man-behind-the-curtain-22131111/?all |author= Asif Siddiqi |title= The Man Behind the Curtain|publisher= Air & Space Magazine |date=November 2007|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> In October 1945, Clarke published an article titled "Extraterrestrial Relays" in the British magazine ''[[Wireless World]]''. <ref>{{cite web| url=http://clarkeinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/04/ClarkeWirelessWorldArticle.pdf |author=Arthur C. Clarke|title= Extraterrestrial Relays: Can Rocket Stations Give World-wide Radio Coverage?|publisher=Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education|date=October 1945|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> The article described the fundamentals behind the deployment of [[satellite|artificial satellite]]s in geostationary orbits for the purpose of relaying radio signals. Thus, Arthur C. Clarke is often quoted as being the [[invention|inventor]] of the concept of the communications satellite, as well as the term 'Clarke Belt' employed as a description of the orbit.<ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1997/08/03/orbit-wars/d5840c66-d2c4-4682-bd95-5f97d46b8843/ |author=Mike Mills|title=Orbit Wars |publisher=The Washington Post |date=3 August 1997|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Work that was begun in the field of electrical intelligence gathering at the [[United States Naval Research Laboratory]] in 1951 led to a project named [[Communication Moon Relay]]. Military planners had long shown considerable interest in secure and reliable communications lines as a tactical necessity, and the ultimate goal of this project was the creation of the longest communications circuit in human history, with the moon, Earth's natural satellite, acting as a passive relay.<ref>{{cite book|last=van Keuren|first=David K.|url=https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4217/ch2.htm|chapter=Chapter 2: Moon in Their Eyes: Moon Communication Relay at the Naval Research Laboratory, 1951-1962|title= Beyond The Ionosphere: Fifty Years of Satellite Communication|editor-last=Butrica|editor-first=Andrew J|publisher=NASA History Office|date=1997}} </ref> |

||

The first [[Satellite|artificial Earth satellite]] was [[Sputnik 1]]. Put into orbit by the [[Soviet Union]] on October 4, 1957, it was equipped with an on-board [[radio]]-[[transmitter]] that worked on two frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 MHz, or 7 and 15 meters wavelength. The satellite was not placed in orbit for the purpose of sending data from one point on earth to another; the radio transmitter was meant to study the properties of radio wave distribution throughout the ionosphere. The launch of Sputnik 1 was a major step in the exploration of space and rocket development, and marks the beginning of the [[Space Age]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.russianspaceweb.com/sputnik_design.html |author=Anatoly Zak|title= Design of the first artificial satellite of the Earth |publisher= RussianSpaceWeb.com |date=2017|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

The first [[Satellite|artificial Earth satellite]] was [[Sputnik 1]]. Put into orbit by the [[Soviet Union]] on October 4, 1957, it was equipped with an on-board [[radio]]-[[transmitter]] that worked on two frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 MHz, or 7 and 15 meters wavelength. The satellite was not placed in orbit for the purpose of sending data from one point on earth to another; the radio transmitter was meant to study the properties of radio wave distribution throughout the ionosphere. The launch of Sputnik 1 was a major step in the exploration of space and rocket development, and marks the beginning of the [[Space Age]].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.russianspaceweb.com/sputnik_design.html |author=Anatoly Zak|title= Design of the first artificial satellite of the Earth |publisher= RussianSpaceWeb.com |date=2017|access-date=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

||

| Line 16: | Line 14: | ||

===Active and passive satellite operation=== |

===Active and passive satellite operation=== |

||

There are two major classes of communications satellites, ''[[Balloon satellite|passive]]'' and ''active''. Passive satellites only [[Reflector (antenna)|reflect]] the signal coming from the source, toward the direction of the receiver. With passive satellites, the reflected signal is not amplified at the satellite, and only a very small amount of the transmitted energy actually reaches the receiver. Since the satellite is so far above Earth, the radio signal is attenuated due to [[free-space path loss]], so the signal received on Earth is very, very weak. Active satellites, on the other hand, amplify the received signal before retransmitting it to the receiver on the ground.<ref name="aerospace.org">{{cite web |url=http://www.aerospace.org/2013/12/12/military-satellite-communications-fundamentals/ |title=Military Satellite Communications Fundamentals | The Aerospace Corporation |website=Aerospace |date=2010-04-01 |access-date=2016-02-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150905170449/http://www.aerospace.org/2013/12/12/military-satellite-communications-fundamentals/ |archive-date=2015-09-05 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Passive satellites were the first communications satellites, but are little used now. |

There are two major classes of communications satellites, ''[[Balloon satellite|passive]]'' and ''active''. Passive satellites only [[Reflector (antenna)|reflect]] the signal coming from the source, toward the direction of the receiver. With passive satellites, the reflected signal is not amplified at the satellite, and only a very small amount of the transmitted energy actually reaches the receiver. Since the satellite is so far above Earth, the radio signal is attenuated due to [[free-space path loss]], so the signal received on Earth is very, very weak. Active satellites, on the other hand, amplify the received signal before retransmitting it to the receiver on the ground.<ref name="aerospace.org">{{cite web |url=http://www.aerospace.org/2013/12/12/military-satellite-communications-fundamentals/ |title=Military Satellite Communications Fundamentals | The Aerospace Corporation |website=Aerospace |date=2010-04-01 |access-date=2016-02-10 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150905170449/http://www.aerospace.org/2013/12/12/military-satellite-communications-fundamentals/ |archive-date=2015-09-05 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Passive satellites were the first communications satellites, but are little used now. |

||

| ⚫ | Work that was begun in the field of electrical intelligence gathering at the [[United States Naval Research Laboratory]] in 1951 led to a project named [[Communication Moon Relay]]. Military planners had long shown considerable interest in secure and reliable communications lines as a tactical necessity, and the ultimate goal of this project was the creation of the longest communications circuit in human history, with the moon, Earth's natural satellite, acting as a passive relay. This systems was publicly inaugurated and put into formal production in January 1960.<ref>{{cite book|last=van Keuren|first=David K.|url=https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4217/ch2.htm|chapter=Chapter 2: Moon in Their Eyes: Moon Communication Relay at the Naval Research Laboratory, 1951-1962|title= Beyond The Ionosphere: Fifty Years of Satellite Communication|editor-last=Butrica|editor-first=Andrew J|publisher=NASA History Office|date=1997}} </ref> |

||

The first satellite to relay communications from specific ground stations was [[Pioneer 1]], an intended lunar probe that was launched on October 11, 1958. Although the spacecraft only made it about halfway to the moon, it flew high enough to carry out the proof of concept relay of telemetry across the world, first from Cape Canaveral to Manchester, England; then from Hawaii to Cape Canaveral; and finally, across the world from Hawaii to Manchester.<ref name = pioneering2>{{cite web|url= https://www.sdfo.org/stl/Pioneer%20Part%20III.pdf |last=Marcus|first=Gideon|title= Pioneering Space Part II|publisher=Quest Magazine|date=2007|accessdate=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

The first satellite to relay communications from specific ground stations was [[Pioneer 1]], an intended lunar probe that was launched on October 11, 1958. Although the spacecraft only made it about halfway to the moon, it flew high enough to carry out the proof of concept relay of telemetry across the world, first from Cape Canaveral to Manchester, England; then from Hawaii to Cape Canaveral; and finally, across the world from Hawaii to Manchester.<ref name = pioneering2>{{cite web|url= https://www.sdfo.org/stl/Pioneer%20Part%20III.pdf |last=Marcus|first=Gideon|title= Pioneering Space Part II|publisher=Quest Magazine|date=2007|accessdate=1 January 2021}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 19:15, 2 January 2021

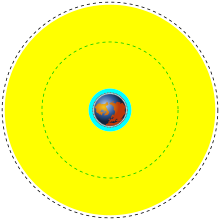

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunications signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth. Communications satellites are used for television, telephone, radio, internet, and military applications.[1] As of 1 August 2020, there are 2,787 artificial satellites in Earth's orbit, with 1,364 of these being communications satellites, used by both private and government organizations.[2] Many are in geostationary orbit 22,236 miles (35,785 km) above the equator, so that the satellite appears stationary at the same point in the sky, so the satellite dish antennas of ground stations can be aimed permanently at that spot and do not have to move to track it.

The high frequency radio waves used for telecommunications links travel by line of sight and so are obstructed by the curve of the Earth. The purpose of communications satellites is to relay the signal around the curve of the Earth allowing communication between widely separated geographical points.[3] Communications satellites use a wide range of radio and microwave frequencies. To avoid signal interference, international organizations have regulations for which frequency ranges or "bands" certain organizations are allowed to use. This allocation of bands minimizes the risk of signal interference.[4]

History

Origins to first artificial satellite

The concept of the geostationary communications satellite was first proposed by Arthur C. Clarke, along with Mikhail Tikhonravov and Sergey Korolev building on work by Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. [5] In October 1945, Clarke published an article titled "Extraterrestrial Relays" in the British magazine Wireless World. [6] The article described the fundamentals behind the deployment of artificial satellites in geostationary orbits for the purpose of relaying radio signals. Thus, Arthur C. Clarke is often quoted as being the inventor of the concept of the communications satellite, as well as the term 'Clarke Belt' employed as a description of the orbit.[7]

The first artificial Earth satellite was Sputnik 1. Put into orbit by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, it was equipped with an on-board radio-transmitter that worked on two frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 MHz, or 7 and 15 meters wavelength. The satellite was not placed in orbit for the purpose of sending data from one point on earth to another; the radio transmitter was meant to study the properties of radio wave distribution throughout the ionosphere. The launch of Sputnik 1 was a major step in the exploration of space and rocket development, and marks the beginning of the Space Age.[8]

Active and passive satellite operation

There are two major classes of communications satellites, passive and active. Passive satellites only reflect the signal coming from the source, toward the direction of the receiver. With passive satellites, the reflected signal is not amplified at the satellite, and only a very small amount of the transmitted energy actually reaches the receiver. Since the satellite is so far above Earth, the radio signal is attenuated due to free-space path loss, so the signal received on Earth is very, very weak. Active satellites, on the other hand, amplify the received signal before retransmitting it to the receiver on the ground.[4] Passive satellites were the first communications satellites, but are little used now.

Work that was begun in the field of electrical intelligence gathering at the United States Naval Research Laboratory in 1951 led to a project named Communication Moon Relay. Military planners had long shown considerable interest in secure and reliable communications lines as a tactical necessity, and the ultimate goal of this project was the creation of the longest communications circuit in human history, with the moon, Earth's natural satellite, acting as a passive relay. This systems was publicly inaugurated and put into formal production in January 1960.[9]

The first satellite to relay communications from specific ground stations was Pioneer 1, an intended lunar probe that was launched on October 11, 1958. Although the spacecraft only made it about halfway to the moon, it flew high enough to carry out the proof of concept relay of telemetry across the world, first from Cape Canaveral to Manchester, England; then from Hawaii to Cape Canaveral; and finally, across the world from Hawaii to Manchester.[10]

The first satellite purpose-built to relay communications was NASA's Project SCORE launched on 18 December 1958, which used a tape recorder to carry a stored voice message, as well as to receive, store, and retransmit messages. It was used to send a Christmas greeting to the world from U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The satellite also executed several realtime transmissions before the non-rechargeable batteries failed on 30 December 1958 after 8 hours of actual operation.[11] Courier 1B, built by Philco, launched in 1960, was the world's first active repeater satellite.

The first artificial satellite used solely to further advances in global communications was a balloon named Echo 1.[12] Echo 1 was the world's first artificial communications satellite capable of relaying signals to other points on Earth. It soared 1,600 kilometres (1,000 mi) above the planet after its Aug. 12, 1960 launch. Launched by NASA, Echo 1 was a 30-metre (100 ft) aluminized PET film balloon that served as a passive reflector for radio communications. The world's first inflatable satellite — or "satelloon", as they were informally known — helped lay the foundation of today's satellite communications. The idea behind a communications satellite is simple: Send data up into space and beam it back down to another spot on the globe. Echo 1 accomplished this by essentially serving as an enormous mirror, 10 stories tall, that could be used to reflect communications signals.

Telstar was the second active, direct relay communications satellite. Belonging to AT&T as part of a multi-national agreement between AT&T, Bell Telephone Laboratories, NASA, the British General Post Office, and the French National PTT (Post Office) to develop satellite communications, it was launched by NASA from Cape Canaveral on July 10, 1962, in the first privately sponsored space launch. Relay 1 was launched on December 13, 1962, and it became the first satellite to transmit across the Pacific Ocean on November 22, 1963.[13]

An immediate antecedent of the geostationary satellites was the Hughes Aircraft Company's Syncom 2, launched on July 26, 1963. Syncom 2 was the first communications satellite in a geosynchronous orbit. It revolved around the earth once per day at constant speed, but because it still had north–south motion, special equipment was needed to track it. Its successor, Syncom 3 was the first geostationary communications satellite. Syncom 3 obtained a geosynchronous orbit, without a north–south motion, making it appear from the ground as a stationary object in the sky.

Beginning with the Viking program,[a] all Mars landers, aside from Mars Pathfinder, have used orbiting spacecraft as communications satellites for relaying their data to Earth. The landers use UHF transmitters to send their data to the orbiters, which then relay the data to Earth using either X band or Ka band frequencies. These higher frequencies, along with more powerful transmitters and larger antennas, permit the orbiters to send the data much faster than the landers could manage transmitting directly to Earth, which conserves valuable time on the receiving antennas.[14]

Satellite orbits

Communications satellites usually have one of three primary types of orbit, while other orbital classifications are used to further specify orbital details.

- Geostationary satellites have a geostationary orbit (GEO), which is 22,236 miles (35,785 km) from Earth's surface. This orbit has the special characteristic that the apparent position of the satellite in the sky when viewed by a ground observer does not change, the satellite appears to "stand still" in the sky. This is because the satellite's orbital period is the same as the rotation rate of the Earth. The advantage of this orbit is that ground antennas do not have to track the satellite across the sky, they can be fixed to point at the location in the sky the satellite appears.

- Medium Earth orbit (MEO) satellites are closer to Earth. Orbital altitudes range from 2,000 to 36,000 kilometres (1,200 to 22,400 mi) above Earth.

- The region below medium orbits is referred to as low Earth orbit (LEO), and is about 160 to 2,000 kilometres (99 to 1,243 mi) above Earth.

As satellites in MEO and LEO orbit the Earth faster, they do not remain visible in the sky to a fixed point on Earth continually like a geostationary satellite, but appear to a ground observer to cross the sky and "set" when they go behind the Earth. Therefore, to provide continuous communications capability with these lower orbits requires a larger number of satellites, so one will always be in the sky for transmission of communication signals. However, due to their relatively small distance to the Earth their signals are stronger.[clarification needed]

Low Earth orbit (LEO)

A low Earth orbit (LEO) typically is a circular orbit about 160 to 2,000 kilometres (99 to 1,243 mi) above the earth's surface and, correspondingly, a period (time to revolve around the earth) of about 90 minutes.[15]

Because of their low altitude, these satellites are only visible from within a radius of roughly 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from the sub-satellite point. In addition, satellites in low earth orbit change their position relative to the ground position quickly. So even for local applications, many satellites are needed if the mission requires uninterrupted connectivity.

Low-Earth-orbiting satellites are less expensive to launch into orbit than geostationary satellites and, due to proximity to the ground, do not require as high signal strength (Recall that signal strength falls off as the square of the distance from the source, so the effect is dramatic). Thus there is a trade off between the number of satellites and their cost.

In addition, there are important differences in the onboard and ground equipment needed to support the two types of missions.

Satellite constellation

A group of satellites working in concert is known as a satellite constellation. Two such constellations, intended to provide satellite phone services, primarily to remote areas, are the Iridium and Globalstar systems. The Iridium system has 66 satellites.

It is also possible to offer discontinuous coverage using a low-Earth-orbit satellite capable of storing data received while passing over one part of Earth and transmitting it later while passing over another part. This will be the case with the CASCADE system of Canada's CASSIOPE communications satellite. Another system using this store and forward method is Orbcomm.

Medium Earth orbit (MEO)

A MEO is a satellite in orbit somewhere between 2,000 and 35,786 kilometres (1,243 and 22,236 mi) above the earth's surface. MEO satellites are similar to LEO satellites in functionality. MEO satellites are visible for much longer periods of time than LEO satellites, usually between 2 and 8 hours. MEO satellites have a larger coverage area than LEO satellites. A MEO satellite's longer duration of visibility and wider footprint means fewer satellites are needed in a MEO network than a LEO network. One disadvantage is that a MEO satellite's distance gives it a longer time delay and weaker signal than a LEO satellite, although these limitations are not as severe as those of a GEO satellite.

Like LEOs, these satellites do not maintain a stationary distance from the earth. This is in contrast to the geostationary orbit, where satellites are always 35,786 kilometres (22,236 mi) from the earth.

Typically the orbit of a medium earth orbit satellite is about 16,000 kilometres (10,000 mi) above earth. In various patterns, these satellites make the trip around earth in anywhere from 2 to 8 hours.

Examples of MEO

- In 1962, the communications satellite, Telstar, was launched. It was a medium earth orbit satellite designed to help facilitate high-speed telephone signals. Although it was the first practical way to transmit signals over the horizon, its major drawback was soon realised. Because its orbital period of about 2.5 hours did not match the Earth's rotational period of 24 hours, continuous coverage was impossible. It was apparent that multiple MEOs needed to be used in order to provide continuous coverage.

- In 2013 the first four of a constellation of 20 MEO satellites was launched. The O3b satellites provide broadband internet services, in particular to remote locations and maritime and in-flight use, and orbit at an altitude of 8,063 kilometres (5,010 mi)).[16]

Geostationary orbit (GEO)

To an observer on Earth, a satellite in a geostationary orbit appears motionless, in a fixed position in the sky. This is because it revolves around the Earth at Earth's own angular velocity (one revolution per sidereal day, in an equatorial orbit).

A geostationary orbit is useful for communications because ground antennas can be aimed at the satellite without their having to track the satellite's motion. This is relatively inexpensive.

In applications that require many ground antennas, such as DirecTV distribution, the savings in ground equipment can more than outweigh the cost and complexity of placing a satellite into orbit.

Examples of GEO

- The first geostationary satellite was Syncom 3, launched on August 19, 1964, and used for communication across the Pacific starting with television coverage of the 1964 Summer Olympics. Shortly after Syncom 3, Intelsat I, aka Early Bird, was launched on April 6, 1965, and placed in orbit at 28° west longitude. It was the first geostationary satellite for telecommunications over the Atlantic Ocean.

- On November 9, 1972, Canada's first geostationary satellite serving the continent, Anik A1, was launched by Telesat Canada, with the United States following suit with the launch of Westar 1 by Western Union on April 13, 1974.

- On May 30, 1974, the first geostationary communications satellite in the world to be three-axis stabilized was launched: the experimental satellite ATS-6 built for NASA.

- After the launches of the Telstar through Westar 1 satellites, RCA Americom (later GE Americom, now SES) launched Satcom 1 in 1975. It was Satcom 1 that was instrumental in helping early cable TV channels such as WTBS (now TBS), HBO, CBN (now Freeform) and The Weather Channel become successful, because these channels distributed their programming to all of the local cable TV headends using the satellite. Additionally, it was the first satellite used by broadcast television networks in the United States, like ABC, NBC, and CBS, to distribute programming to their local affiliate stations. Satcom 1 was widely used because it had twice the communications capacity of the competing Westar 1 in America (24 transponders as opposed to the 12 of Westar 1), resulting in lower transponder-usage costs. Satellites in later decades tended to have even higher transponder numbers.

By 2000, Hughes Space and Communications (now Boeing Satellite Development Center) had built nearly 40 percent of the more than one hundred satellites in service worldwide. Other major satellite manufacturers include Space Systems/Loral, Orbital Sciences Corporation with the Star Bus series, Indian Space Research Organisation, Lockheed Martin (owns the former RCA Astro Electronics/GE Astro Space business), Northrop Grumman, Alcatel Space, now Thales Alenia Space, with the Spacebus series, and Astrium.

Molniya orbit

Geostationary satellites must operate above the equator and therefore appear lower on the horizon as the receiver gets farther from the equator. This will cause problems for extreme northerly latitudes, affecting connectivity and causing multipath interference (caused by signals reflecting off the ground and into the ground antenna).

Thus, for areas close to the North (and South) Pole, a geostationary satellite may appear below the horizon. Therefore, Molniya orbit satellites have been launched, mainly in Russia, to alleviate this problem.

Molniya orbits can be an appealing alternative in such cases. The Molniya orbit is highly inclined, guaranteeing good elevation over selected positions during the northern portion of the orbit. (Elevation is the extent of the satellite's position above the horizon. Thus, a satellite at the horizon has zero elevation and a satellite directly overhead has elevation of 90 degrees.)

The Molniya orbit is designed so that the satellite spends the great majority of its time over the far northern latitudes, during which its ground footprint moves only slightly. Its period is one half day, so that the satellite is available for operation over the targeted region for six to nine hours every second revolution. In this way a constellation of three Molniya satellites (plus in-orbit spares) can provide uninterrupted coverage.

The first satellite of the Molniya series was launched on April 23, 1965 and was used for experimental transmission of TV signals from a Moscow uplink station to downlink stations located in Siberia and the Russian Far East, in Norilsk, Khabarovsk, Magadan and Vladivostok. In November 1967 Soviet engineers created a unique system of national TV network of satellite television, called Orbita, that was based on Molniya satellites.

Polar orbit

In the United States, the National Polar-orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS) was established in 1994 to consolidate the polar satellite operations of NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). NPOESS manages a number of satellites for various purposes; for example, METSAT for meteorological satellite, EUMETSAT for the European branch of the program, and METOP for meteorological operations.

These orbits are sun synchronous, meaning that they cross the equator at the same local time each day. For example, the satellites in the NPOESS (civilian) orbit will cross the equator, going from south to north, at times 1:30 P.M., 5:30 P.M., and 9:30 P.M.

Structure

Communications Satellites are usually composed of the following subsystems:

- Communication Payload, normally composed of transponders, antennas, and switching systems

- Engines used to bring the satellite to its desired orbit

- A station keeping tracking and stabilization subsystem used to keep the satellite in the right orbit, with its antennas pointed in the right direction, and its power system pointed towards the sun

- Power subsystem, used to power the Satellite systems, normally composed of solar cells, and batteries that maintain power during solar eclipse

- Command and Control subsystem, which maintains communications with ground control stations. The ground control Earth stations monitor the satellite performance and control its functionality during various phases of its life-cycle.

The bandwidth available from a satellite depends upon the number of transponders provided by the satellite. Each service (TV, Voice, Internet, radio) requires a different amount of bandwidth for transmission. This is typically known as link budgeting and a network simulator can be used to arrive at the exact value.

Frequency allocation for satellite systems

Allocating frequencies to satellite services is a complicated process which requires international coordination and planning. This is carried out under the auspices of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU). To facilitate frequency planning, the world is divided into three regions:

- Region 1: Europe, Africa, the Middle East, what was formerly the Soviet Union, and Mongolia

- Region 2: North and South America and Greenland

- Region 3: Asia (excluding region 1 areas), Australia, and the southwest Pacific

Within these regions, frequency bands are allocated to various satellite services, although a given service may be allocated different frequency bands in different regions. Some of the services provided by satellites are:

- Fixed satellite service (FSS)

- Broadcasting satellite service (BSS)

- Mobile-satellite service

- Radionavigation-satellite service

- Meteorological-satellite service

Applications

Telephony

The first and historically most important application for communication satellites was in intercontinental long distance telephony. The fixed Public Switched Telephone Network relays telephone calls from land line telephones to an earth station, where they are then transmitted to a geostationary satellite. The downlink follows an analogous path. Improvements in submarine communications cables through the use of fiber-optics caused some decline in the use of satellites for fixed telephony in the late 20th century.

Satellite communications are still used in many applications today. Remote islands such as Ascension Island, Saint Helena, Diego Garcia, and Easter Island, where no submarine cables are in service, need satellite telephones. There are also regions of some continents and countries where landline telecommunications are rare to nonexistent, for example large regions of South America, Africa, Canada, China, Russia, and Australia. Satellite communications also provide connection to the edges of Antarctica and Greenland. Other land use for satellite phones are rigs at sea, a back up for hospitals, military, and recreation. Ships at sea, as well as planes, often use satellite phones.[17]

Satellite phone systems can be accomplished by a number of means. On a large scale, often there will be a local telephone system in an isolated area with a link to the telephone system in a main land area. There are also services that will patch a radio signal to a telephone system. In this example, almost any type of satellite can be used. Satellite phones connect directly to a constellation of either geostationary or low-Earth-orbit satellites. Calls are then forwarded to a satellite teleport connected to the Public Switched Telephone Network .

Television

As television became the main market, its demand for simultaneous delivery of relatively few signals of large bandwidth to many receivers being a more precise match for the capabilities of geosynchronous comsats. Two satellite types are used for North American television and radio: Direct broadcast satellite (DBS), and Fixed Service Satellite (FSS).

The definitions of FSS and DBS satellites outside of North America, especially in Europe, are a bit more ambiguous. Most satellites used for direct-to-home television in Europe have the same high power output as DBS-class satellites in North America, but use the same linear polarization as FSS-class satellites. Examples of these are the Astra, Eutelsat, and Hotbird spacecraft in orbit over the European continent. Because of this, the terms FSS and DBS are more so used throughout the North American continent, and are uncommon in Europe.

Fixed Service Satellites use the C band, and the lower portions of the Ku band. They are normally used for broadcast feeds to and from television networks and local affiliate stations (such as program feeds for network and syndicated programming, live shots, and backhauls), as well as being used for distance learning by schools and universities, business television (BTV), Videoconferencing, and general commercial telecommunications. FSS satellites are also used to distribute national cable channels to cable television headends.

Free-to-air satellite TV channels are also usually distributed on FSS satellites in the Ku band. The Intelsat Americas 5, Galaxy 10R and AMC 3 satellites over North America provide a quite large amount of FTA channels on their Ku band transponders.

The American Dish Network DBS service has also recently used FSS technology as well for their programming packages requiring their SuperDish antenna, due to Dish Network needing more capacity to carry local television stations per the FCC's "must-carry" regulations, and for more bandwidth to carry HDTV channels.

A direct broadcast satellite is a communications satellite that transmits to small DBS satellite dishes (usually 18 to 24 inches or 45 to 60 cm in diameter). Direct broadcast satellites generally operate in the upper portion of the microwave Ku band. DBS technology is used for DTH-oriented (Direct-To-Home) satellite TV services, such as DirecTV, DISH Network and Orby TV[18] in the United States, Bell Satellite TV and Shaw Direct in Canada, Freesat and Sky in the UK, Ireland, and New Zealand and DSTV in South Africa.

Operating at lower frequency and lower power than DBS, FSS satellites require a much larger dish for reception (3 to 8 feet (1 to 2.5 m) in diameter for Ku band, and 12 feet (3.6 m) or larger for C band). They use linear polarization for each of the transponders' RF input and output (as opposed to circular polarization used by DBS satellites), but this is a minor technical difference that users do not notice. FSS satellite technology was also originally used for DTH satellite TV from the late 1970s to the early 1990s in the United States in the form of TVRO (TeleVision Receive Only) receivers and dishes. It was also used in its Ku band form for the now-defunct Primestar satellite TV service.

Some satellites have been launched that have transponders in the Ka band, such as DirecTV's SPACEWAY-1 satellite, and Anik F2. NASA and ISRO[19][20] have also launched experimental satellites carrying Ka band beacons recently.[21]

Some manufacturers have also introduced special antennas for mobile reception of DBS television. Using Global Positioning System (GPS) technology as a reference, these antennas automatically re-aim to the satellite no matter where or how the vehicle (on which the antenna is mounted) is situated. These mobile satellite antennas are popular with some recreational vehicle owners. Such mobile DBS antennas are also used by JetBlue Airways for DirecTV (supplied by LiveTV, a subsidiary of JetBlue), which passengers can view on-board on LCD screens mounted in the seats.

Radio broadcasting

Satellite radio offers audio broadcast services in some countries, notably the United States. Mobile services allow listeners to roam a continent, listening to the same audio programming anywhere.

A satellite radio or subscription radio (SR) is a digital radio signal that is broadcast by a communications satellite, which covers a much wider geographical range than terrestrial radio signals.

Satellite radio offers a meaningful alternative to ground-based radio services in some countries, notably the United States. Mobile services, such as SiriusXM, and Worldspace, allow listeners to roam across an entire continent, listening to the same audio programming anywhere they go. Other services, such as Music Choice or Muzak's satellite-delivered content, require a fixed-location receiver and a dish antenna. In all cases, the antenna must have a clear view to the satellites. In areas where tall buildings, bridges, or even parking garages obscure the signal, repeaters can be placed to make the signal available to listeners.

Initially available for broadcast to stationary TV receivers, by 2004 popular mobile direct broadcast applications made their appearance with the arrival of two satellite radio systems in the United States: Sirius and XM Satellite Radio Holdings. Later they merged to become the conglomerate SiriusXM.

Radio services are usually provided by commercial ventures and are subscription-based. The various services are proprietary signals, requiring specialized hardware for decoding and playback. Providers usually carry a variety of news, weather, sports, and music channels, with the music channels generally being commercial-free.

In areas with a relatively high population density, it is easier and less expensive to reach the bulk of the population with terrestrial broadcasts. Thus in the UK and some other countries, the contemporary evolution of radio services is focused on Digital Audio Broadcasting (DAB) services or HD Radio, rather than satellite radio.

Amateur radio

Amateur radio operators have access to amateur satellites, which have been designed specifically to carry amateur radio traffic. Most such satellites operate as spaceborne repeaters, and are generally accessed by amateurs equipped with UHF or VHF radio equipment and highly directional antennas such as Yagis or dish antennas. Due to launch costs, most current amateur satellites are launched into fairly low Earth orbits, and are designed to deal with only a limited number of brief contacts at any given time. Some satellites also provide data-forwarding services using the X.25 or similar protocols.

Internet access

After the 1990s, satellite communication technology has been used as a means to connect to the Internet via broadband data connections. This can be very useful for users who are located in remote areas, and cannot access a broadband connection, or require high availability of services.

Military

Communications satellites are used for military communications applications, such as Global Command and Control Systems. Examples of military systems that use communication satellites are the MILSTAR, the DSCS, and the FLTSATCOM of the United States, NATO satellites, United Kingdom satellites (for instance Skynet), and satellites of the former Soviet Union. India has launched its first Military Communication satellite GSAT-7, its transponders operate in UHF, F, C and Ku band bands.[22] Typically military satellites operate in the UHF, SHF (also known as X-band) or EHF (also known as Ka band) frequency bands.

Data collection

Near-ground in situ environmental monitoring equipment (such as weather stations, weather buoys, and radiosondes), may use satellites for one-way data transmission or two-way telemetry and telecontrol.[23][24] It may be based on a secondary payload of a weather satellite (as in the case of GOES and METEOSAT and others in the Argos system) or in dedicated satellites (such as SCD). The data rate is typically much lower than in satellite Internet access.

See also

- Commercialization of space

- History of telecommunication

- Inter-satellite communications satellite

- List of communication satellite companies

- List of communications satellite firsts

- NewSpace

- Reconnaissance satellite

- Relay (disambiguation)

- Satcom On The Move

- Satellite data unit

- Satellite delay

- Satellite space segment

- Space pollution

References

Notes

- ^ The last Viking lander reverted to Earth-direct communications after both orbiters expired.

Citations

- ^ Labrador, Virgil (2015-02-19). "satellite communication". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ "UCS Satellite Database". Union of Concerned Scientists. 1 August 2020. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ "Satellites - Communication Satellites". Satellites.spacesim.org. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ a b "Military Satellite Communications Fundamentals | The Aerospace Corporation". Aerospace. 2010-04-01. Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

- ^ Asif Siddiqi (November 2007). "The Man Behind the Curtain". Air & Space Magazine. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Arthur C. Clarke (October 1945). "Extraterrestrial Relays: Can Rocket Stations Give World-wide Radio Coverage?" (PDF). Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Mike Mills (3 August 1997). "Orbit Wars". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Anatoly Zak (2017). "Design of the first artificial satellite of the Earth". RussianSpaceWeb.com. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ van Keuren, David K. (1997). "Chapter 2: Moon in Their Eyes: Moon Communication Relay at the Naval Research Laboratory, 1951-1962". In Butrica, Andrew J (ed.). Beyond The Ionosphere: Fifty Years of Satellite Communication. NASA History Office.

- ^ Marcus, Gideon (2007). "Pioneering Space Part II" (PDF). Quest Magazine. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Martin, Donald; Anderson, Paul; Bartamian, Lucy (March 16, 2007). Communications Satellites (5th ed.). AIAA. ISBN 978-1884989193.

- ^ ECHO 1 space.com

- ^ "Significant Achievements in Space Communications and Navigation, 1958-1964" (PDF). NASA-SP-93. NASA. 1966. pp. 30–32. Retrieved 2009-10-31.

- ^ "Talking to Martians: Communications with Mars Curiosity Rover". Steven Gordon's Home Page. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "IADC Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines" (PDF). INTER-AGENCY SPACE DEBRIS COORDINATION COMMITTEE: Issued by Steering Group and Working Group 4. September 2007.

Region A, Low Earth Orbit (or LEO) Region – spherical region that extends from the Earth's surface up to an altitude (Z) of 2,000 km

- ^ Soyuz Flight VS05 Launch Kit Arianespace. June 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2020

- ^ Connected | Maritime Archived 2013-08-15 at the Wayback Machine. Iridium. Retrieved on 2013-09-19.

- ^ "Orby TV (United States)". Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "GSAT-14". ISRO. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "Indian GSLV successfully lofts GSAT-14 satellite". NASA Space Flight. 4 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ "DIRECTV's Spaceway F1 Satellite Launches New Era in High-Definition Programming; Next Generation Satellite Will Initiate Historic Expansion of DIRECTV". SpaceRef. Retrieved 2012-05-11.

- ^ India's first 'military' satellite GSAT-7 put into earth's orbit. NDTV.com (2013-09-04). Retrieved on 2013-09-18.

- ^ Kramer, Herbert J. (2002). "Data Collection (Messaging) Systems". Observation of the Earth and Its Environment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 311–328. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-56294-5_4. ISBN 978-3-642-62688-3.

- ^ "Satellite Data Telecommunication Handbook". library.wmo.int. Retrieved 2020-12-21.